Consumers’ Intentions towards Green Hotels in China: An Empirical Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Hotel Practices

2.2. Normative Activation Model (NAM)

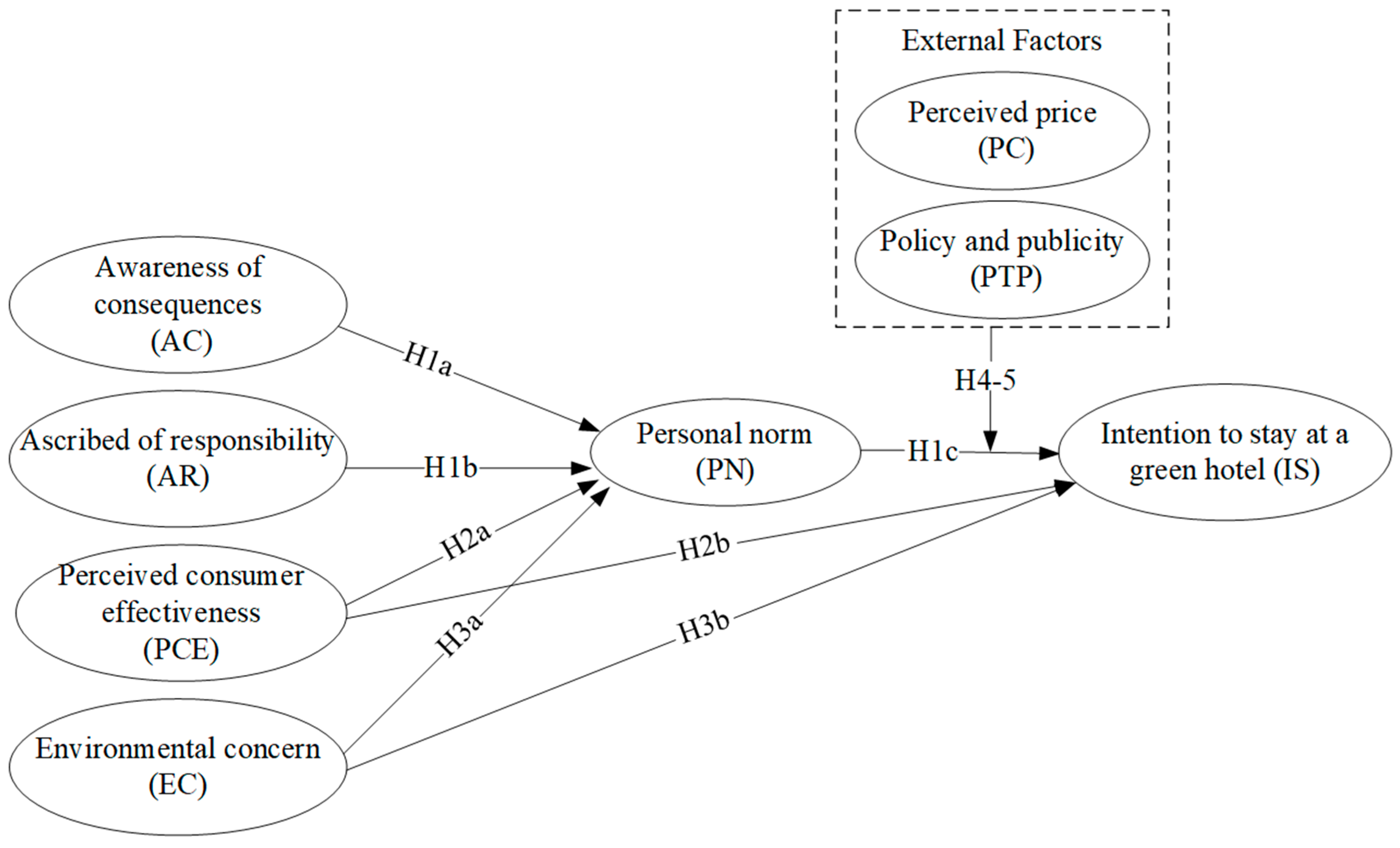

3. Investigation Model and Assumptions

3.1. The NAM Original Model

3.2. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness

3.3. Environmental Concern

3.4. The Moderating Effect of Perceived Price

3.5. The Moderating Effect of Policy and Publicity

4. Research Design

4.1. Questionnaire Design

4.2. Samples and Procedures

4.3. The Variance of Common Methods

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model Testing

5.2. Result of Structural Model

5.3. Mediation Impact Testing

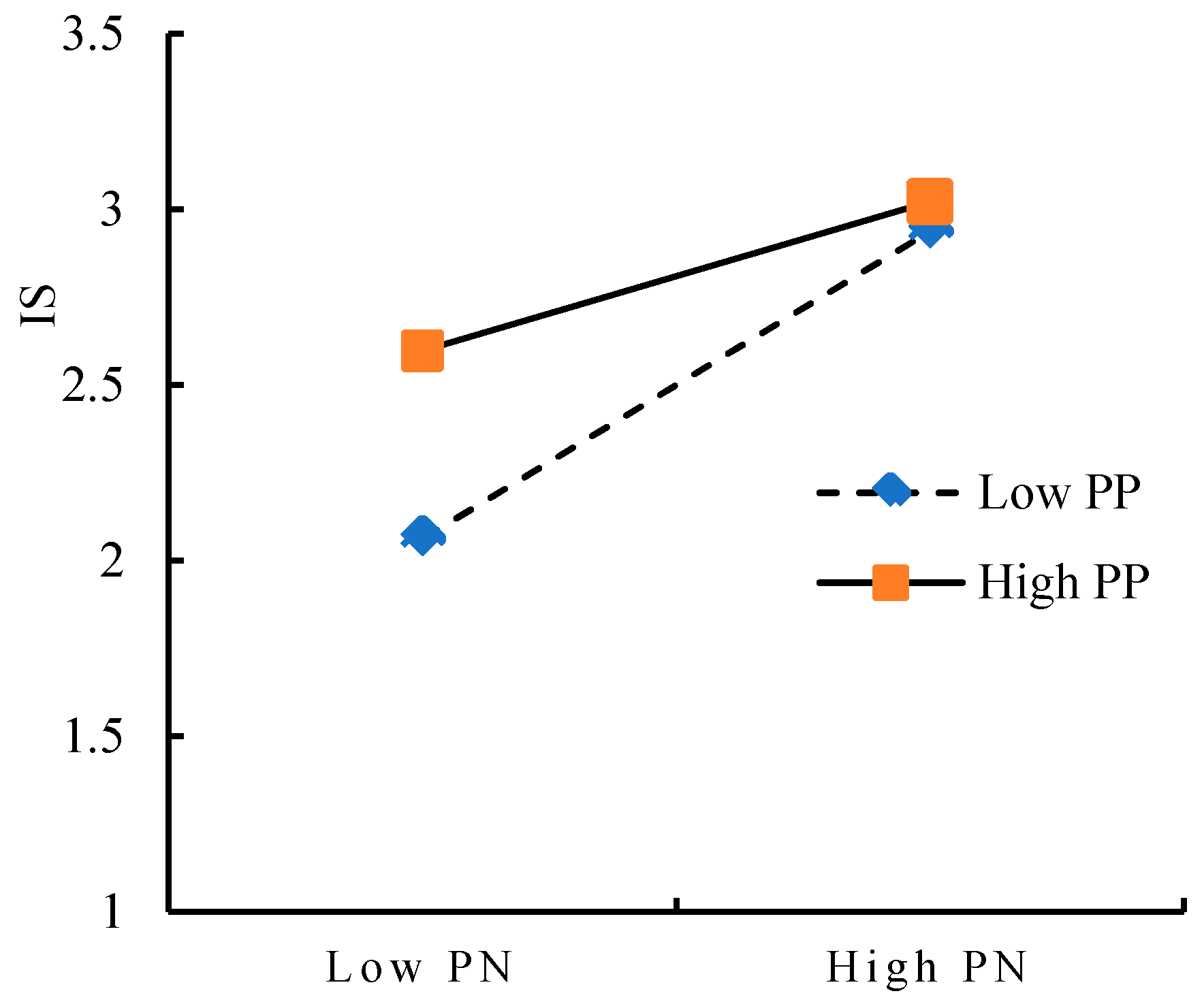

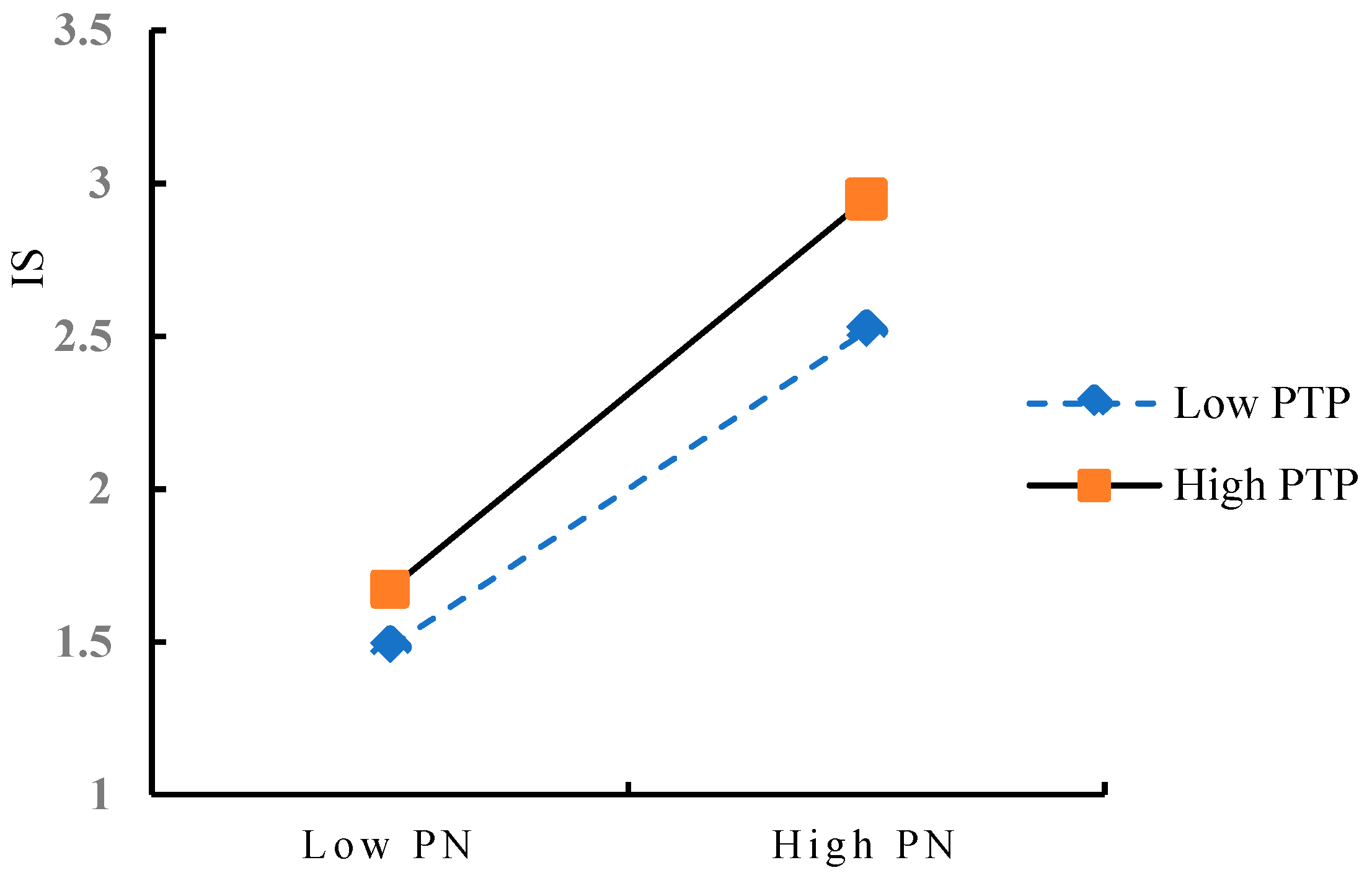

5.4. Adjustment Effect Testing

6. Discussion and Implication

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Research Implications

6.3. Restriction and Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Construct and Its Measurement Indicators

| Construct | Source | |

| Awareness of consequences | ||

| AC1 | Hotels cause pollution, climate change, and depletion of natural resources | Bamberg and Schmidt (2003) |

| AC2 | The hotel will have an environmental impact on the surrounding area and the broader environment | |

| AC3 | Hotels can lead to environmental degradation such as waste, energy/water overuse in guest rooms, restaurants, and other facilities | |

| AC4 | Environmentally responsible hotels implement energy/water conservation, waste reduction, and environmental activities to minimize environmental degradation | |

| Ascribed sense of responsibility | ||

| AR1 | I believe that every hotel guest is partly responsible for the environmental issues resulting from the hotel sector | Onwezen et al. (2013) |

| AR2 | I feel that the hotel industry is responsible for the deterioration of the hotel environment | |

| AR3 | Every hotel guest must be responsible for the environmental issues resulting from the hotel | |

| Personal norm | ||

| PN1 | Living in a green hotel and employing green products/services will make me a better person | Beck and Ajzen (1991) |

| PN2 | Unlike traditional hotels, living in a green hotel makes me feel like a moral person | |

| PN3 | If I don’t stay at the green hotel, I feel guilty | |

| Perceived consumereffectiveness | ||

| PCE1 | Staying at a green hotel, everyone’s behavior will positively affect society | Kim and Choi |

| PCE2 | I think staying in a green hotel can help save energy | (2005) |

| PCE3 | I think staying in a green hotel helps protect the environment | |

| PCE4 | I can’t do anything about protecting environment | |

| Environmentalconcern | ||

| EC1 | I greatly focus on environmental issues | Smith and |

| EC2 | I have a sense of mission to conserve energy and protect environment | McSweeney (2007) |

| EC3 | I think choosing to stay at green hotel can reduce environment pollution | |

| Perceived price | ||

| PC1 | The price of a green hotel is expensive | Petrick (2002) |

| PC2 | The price of a green hotel is higher than a non-green hotel | |

| PC3 | The price of a green hotel is higher than I expected | |

| Policy and publicity | ||

| PTP1 | I’ve heard about the subsidy policy about staying at the green hotel | Smith and |

| PTP2 | Energy conservation and environmental protection work in our district has been greatly promoted | McSweeney (2007) |

| PTP3 | Policy advocacy of energy conservation and environmental protection behavior will motivate me to choose a green hotel | |

| Intention to stay at a green hotel | ||

| IS1 | I’d like to stay at a green hotel when I travel | Chen and Tung (2014) |

| IS2 | I plan to stay at a green hotel when I travel | |

| IS3 | I try to stay at a green hotel when I travel | |

References

- Alzboun, N.; Khawaldah, H.; Backman, K.; Moore, D. The effect of sustainability practices on financial leakage in the hotel industry in Jordan. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 27, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. Direct and indirect effects of eco-innovation, environmentalorientation and supplier collaboration on hotel performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.R.; Dodds, R. Measuring the choice of environmental sustainability strategies in creating a competitive advantage. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 672–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Jin, X. The determinants of consumers’ intention of purchasing green hotel accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.; Agag, G.; Shehawy, Y. Understanding guests’ intention to visit green hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dash, S.; Mishra, A. All that glitters is not green: Creating trustworthy eco- friendly services at green hotels. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; Colmekcioglu, N. Understanding guests’ behavior to visit green hotels: The role of ethical ideology and religiosity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging Context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Ajzen, I. Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. J. Res. Pers. 1991, 25, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blobaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Møller, M.; Haustein, S.; Bohlbro, M.S. Adolescents’ associations between travel behavior and environmental impact: A qualitative study based on the norm-activation model. Travel Behav. Soc. 2018, 11, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, M. Does haze pollution promote the consumption of energy-saving appliances in China? An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. The norm activation model and theory-broadening: Individuals’ decision making on environmentally-responsible convention attendance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chen, C.; Lho, L.H.; Kim, H.; Yu, J. Green Hotels: Exploringthe Drivers of Customer Approach Behaviors for Green Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Hotel Association (GHA). What are a Green Hotel? 2008. Available online: http://www.greenhotels.com/index.php (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Lee, J.S.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, J.; Trang, H.l.T.; Kim, W. Water conservation and waste reduction management for increasing guest loyalty and green hotel practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. What influences water conservation and towel reuse practices of hotel guests? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral Intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Apaolaza, V.; Hartmann, P.; Brouwer, A.R. Marketing for sustainability: Travellers’ intentions to stay in green hotels. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. Explanations of the moderating effect of responsibility denial on the personal norm-behavior relationship. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1980, 43, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M. Recycling as altruistic behavior normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, V.D.W.; Steg, L. One model to predict them all: Predicting energy behaviours with the norm activation model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Jung, H. Guests’ pro-environmental decision making process: Broadening the norm activation framework in a lodging context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 47, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Wiener, J.L.; Cobb-Walgren, C. The role of perceived consumereffectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.C.; James, T.R.; Sadrudin, A.A. Ecologically concerned consumers: Who are they? J. Market. 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.H. Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.V.; Nguyen, N.; Pervan, S. Retailer corporate social responsibility and consumer citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of perceived consumer effectiveness and consumer trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.R., Jr. The environmentally concerned citizen: Some correlates. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojuharenco, I.; Cornelissen, G.; Karelaia, N. Yes, I can: Feeling connected to others increases perceived effectiveness and socially responsible behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Yin, J.; Zhang, B. Purchasing intentions of Chinese citizens on new energy vehicles: How should one respond to current preferential policy? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Babaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing topay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Said, A.; Ahmadun, F.; Paim, L.H.; Masud, J. Environmental concerns, knowledge and practices gap among Malaysian teachers. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2003, 4, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Gouveia, V.V. Time perspective and values: An exploratory study of their relations to environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; Lau, L.B.Y. Antecedents of green purchases: A survey in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S. Environmental concern, attitude toward frugality, and ease of behavior as determinants of pro-environmental behavior intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Verplanken, B.; Olsen, S.O. Ethical values and motives driving organic food choice. J. Consumer Behav. 2006, 5, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W.; Siero, F. General antecedents of personal norms, policy acceptability, and intentions: The role of values, worldviews, and environmental concern. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzler, H.B.; Diekmann, A. All talk and no action? An analysis of environmental concern, income and greenhouse gas emissions in Switzerland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.W.; Liao, H.; Wang, J.-W.; Chen, T.Q. The role of environmental concern in the public acceptance of autonomous electric vehicles: A survey from China. Transp. Res. Part F 2019, 60, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ang, T.; Jancenelle, V.E. intention to pay more for green products: The interplay of consumer characteristics and customer participation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdil, T.S. Effects of customer brand perceptions on store image and purchase intention: An application in apparel clothing. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C.; Lévy-Mangin, J.P. Store brands’ purchase intention: Examining the role of perceived quality. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. Consumer perceptions of price, quality and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. The compelling ‘hard case’ for ‘green hotel’ development. Cornell Hosp. Quar. 2008, 49, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezawada, R.; Pauwels, K. What is special about marketing organic products? How organic assortment, price and performance driver retailer performance. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Huque, S.R.M.; Haroon, M.H.; Shariff, M.N.M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S.; Foster, C. Exploring the gap between attitudes and behavior: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorn, J.V.; Verhoef, P.C. Drivers of and barriers to organic purchase behavior. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.; Ma, X.; Shang, Y. Can China’s policy of carbon emission trading promote carbon emission reduction? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Pan, X.; Li, C.; Song, J.; Zhang, J. Effects of China’s environmental policy on carbon emission Efficiency. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 11, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiers, A.; Neame, C. Consumer attitudes towards domestic solar power systems. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.O.; Clark, C.D.; Jensen, K.L.; Yen, S.T.; Russell, C.S. Factors influencing intention-to-pay for the energy star (R) label. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.T.; Bell, L.; Horner, M.W.; Sulik, J.; Zhang, J.F. Consumer responses towards home energy financial incentives: A survey-based study. Energy Policy 2012, 47, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, morality or habit? Predicting students’car use for university routes with the models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The norm activation model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; McSweeney, A. Charitable giving: The effectiveness of a revised theory of planned behaviour model in predicting donating intentions and behaviour. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 17, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. Development of a multi-dimensional scale for measuring the perceived value of a service. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Jeong-Yeon, L.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Katz-gerro, T. Predicting pro-environmental behavior cross nationally values, the theory of planned behavior, and value-belief norm theory. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 224 | 51.5 |

| Female | 211 | 48.5 | |

| ≤20 | 20 | 4.6 | |

| 21–25 | 87 | 20.0 | |

| Age | 26–35 | 164 | 37.7 |

| 36–45 | 92 | 21.1 | |

| 46–55 | 48 | 11.0 | |

| ≥56 | 24 | 5.5 | |

| Education | Junior high school and below | 28 | 6.4 |

| Senior high school | 88 | 20.2 | |

| bachelor’s degree | 263 | 60.5 | |

| master’s degree and above | 56 | 12.9 | |

| Total monthly income (RMB) | ≤3000 | 68 | 15.6 |

| 3000–5000 | 72 | 16.6 | |

| 5000–8000 | 156 | 35.9 | |

| 8000–10,000 | 119 | 27.4 | |

| ≥10,000 | 20 | 4.6 |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | AC1 | 0.727 | 0.885 | 0.658 | 0.883 |

| AC2 | 0.846 | ||||

| AC3 | 0.839 | ||||

| AC4 | 0.827 | ||||

| AR | AR1 | 0.938 | 0.934 | 0.824 | 0.932 |

| AR2 | 0.865 | ||||

| AR3 | 0.919 | ||||

| PCE | PCE1 | 0.862 | 0.902 | 0.697 | 0.901 |

| PCE2 | 0.843 | ||||

| PCE3 | 0.832 | ||||

| PCE4 | 0.802 | ||||

| EC | EC1 | 0.905 | 0.894 | 0.739 | 0.893 |

| EC2 | 0.865 | ||||

| EC3 | 0.805 | ||||

| PN | PN1 | 0.862 | 0.893 | 0.736 | 0.892 |

| PN2 | 0.825 | ||||

| PN3 | 0.885 | ||||

| PP | PP1 | 0.864 | 0.891 | 0.732 | 0.889 |

| PP2 | 0.899 | ||||

| PP3 | 0.802 | ||||

| PTP | PTP1 | 0.861 | 0.923 | 0.799 | 0.921 |

| PTP2 | 0.926 | ||||

| PTP3 | 0.894 | ||||

| IS | IS1 | 0.852 | 0.895 | 0.739 | 0.895 |

| IS2 | 0.846 | ||||

| IS3 | 0.879 |

| Constructs | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Awareness of Consequences | 3.553 | 1.045 | 0.811 | |||||||

| 2. Ascribed of Responsibility | 3.330 | 1.194 | 0.434 | 0.908 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness | 3.272 | 1.183 | 0.468 | 0.575 | 0.835 | |||||

| 4. Environmental Concern | 3.633 | 1.061 | 0.437 | 0.161 | 0.355 | 0.860 | ||||

| 5. Personal Norm | 3.276 | 1.128 | 0.544 | 0.455 | 0.561 | 0.442 | 0.857 | |||

| 6. Perceived Price | 3.579 | 1.140 | 0.344 | 0.240 | 0.364 | 0.378 | 0.475 | 0.856 | ||

| 7. Policy and Publicity | 3.476 | 1.251 | 0.347 | 0.315 | 0.335 | 0.371 | 0.537 | 0.323 | 0.894 | |

| 8. Stay at a Green Hotel | 3.320 | 1.222 | 0.355 | 0.453 | 0.590 | 0.500 | 0.711 | 0.655 | 0.597 | 0.860 |

| Assumption Path | Standardized | Unstandardized | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a:AC | → | PN | 0.156 | 0.169 | 0.058 | 2.92 | ** |

| H1b:AR | → | PN | 0.218 | 0.197 | 0.048 | 4.078 | *** |

| H1c:PN | → | IS | 0.489 | 0.507 | 0.056 | 9.043 | *** |

| H2a:PCE | → | PN | 0.284 | 0.264 | 0.057 | 4.652 | *** |

| H2b:PCE | → | IS | 0.264 | 0.255 | 0.047 | 5.402 | *** |

| H3a:EC | → | PN | 0.232 | 0.268 | 0.059 | 4.51 | *** |

| H3b:EC | → | IS | 0.187 | 0.224 | 0.053 | 4.261 | *** |

| Path | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCE→IS | Total effect | 0.403 | 0.274 | 0.533 | 0.000 |

| EC→IS | Total effect | 0.301 | 0.197 | 0.41 | 0.000 |

| PCE→IS | Direct effect | 0.264 | 0.143 | 0.393 | 0.000 |

| EC→IS | Direct effect | 0.187 | 0.089 | 0.292 | 0.001 |

| PCE→PN→IS | Indirect effect | 0.139 | 0.075 | 0.219 | 0.000 |

| EC→PN→IS | Indirect effect | 0.113 | 0.060 | 0.181 | 0.001 |

| Variables | IS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Gender | 0.081 | 0.011 | 0.031 | 0.029 | 0.028 |

| Age | 0.039 | 0.019 | 0.015 | 0.031 | 0.033 |

| Education | −0.095 | −0.010 | −0.009 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Income | −0.011 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.021 | 0.021 |

| PN | 0.481 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.517 ** | |

| PP | 0.368 ** | 0.310 ** | |||

| PTP | 0.297 ** | 0.311 ** | |||

| PP*PN | −0.226 ** | ||||

| PTP*PN | 0.121 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.007 | 0.519 | 0.563 | 0.476 | 0.489 |

| Adj-R2 | −0.002 | 0.513 | 0.556 | 0.468 | 0.481 |

| ΔF | 0.781 | 227.938 *** | 42.587 *** | 191.188 *** | 11.195 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, H.; Chai, H. Consumers’ Intentions towards Green Hotels in China: An Empirical Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2165. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042165

Yan H, Chai H. Consumers’ Intentions towards Green Hotels in China: An Empirical Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Model. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2165. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042165

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Hongru, and Huaqi Chai. 2021. "Consumers’ Intentions towards Green Hotels in China: An Empirical Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Model" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2165. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042165

APA StyleYan, H., & Chai, H. (2021). Consumers’ Intentions towards Green Hotels in China: An Empirical Study Based on Extended Norm Activation Model. Sustainability, 13(4), 2165. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042165