1. Introduction

In modern economies, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are the main component in what concerns their number, but also their importance in creating jobs and income for society. SMEs from the Eastern border of the EU face difficult times in dealing with political and economic changes. The paper presents the results of an exploratory research of the training needs of the employees from SMEs of the cross-border area of Romania-Republic of Moldova–Ukraine (RO–MD–UA), more specifically, from Suceava County (RO), the Bălți Region (MD), and the Chernivtsi Region (UA). Being remote areas, the challenges that the SMEs are facing on their way to success are significant. One of these challenges is access to well-qualified employees who are well-motivated and willing to stay in the region and to make their best for their employers. For this reason, the training of human resources, as a main function of personnel management, gains a higher importance, aiming to complete the initial school/academic education.

The paper highlights the perception of the SMEs human resources on training programs organized in companies. Through our investigation, the employees’ expectations regarding the training needs are directly connected with the activity and the needs of the companies and could be interpreted as an economic indicator for the SMEs activity in this Eastern corner of Europe. The specificities of the management of SMEs, compared with large, well-established companies, involve a different approach to human resources training and development [

1]; a lot of researchers have identified these specificities. Some activities dedicated to training of human resources are prohibitive due to high costs associated or due to other priorities in investment, expansion of the markets, and acquisition of new technologies.

The SMEs are focused on business priorities that sometimes overshadow the knowledge or the well-being of the employees. What are the employees’ thoughts and opinions with regards to this? The purpose of the current research paper was to identify the training needs of entrepreneurs and employees within SMEs from the Suceava, Chernivtsi, and Bălți regions, to analyze the specific training practices in the cross-border area, and to identify the common features or the disparities.

Using the related literature, our study highlights the place of the SMEs in the economy and reveals some aspects regarding the training needs and techniques in SMEs and their importance as an indicator for the enterprise needs.

The relevance of our work is also given by its trans-regional approach and by the fact that it tackles a very actual subject: the human resources training needs in the SMEs from a cross-border area. It links the SMEs and the human resources, given their potential in contributing to the development of a cross-border region.

Nevertheless, the paper is answering a call for additional research on employee training [

2]. As well, according to Zhang et al., “previous research has mainly focused on a single enterprise, neglecting the perspective on multiple enterprises” [

2].

The structure of the paper corresponds to the objectives we set out initially to achieve. In the first part, it includes a relevant literature review on SMEs and transition economies, SMEs, and human resources. This work highlights the place of the SMEs in the economy and reveals some aspects regarding the human resources training needs and techniques in SMEs. The paper continues with the analysis of human resources needs and perception regarding the training programs organized by SMEs in the three regions of this cross-border area, which includes the objectives and research methodology, followed by presentation of the research results.

Lifelong learning is an important component of the European Union (EU) strategy for smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth. Job-related adult learning and continuing vocational training play an essential role in this respect. The Adult Education Survey (AES) and the Continuing Vocational Training Survey (CVTS) are key statistical sources at the EU level that complement and help understand the benchmark indicator on participation in adult education and training derived from the EU labor force survey (LFS) [

3].

According to AES-2011, in the EU, an average of 40.3% of adults (25–64 year-olds) have participated in some form of formal or non-formal learning within the 12 months prior to the survey. AES shows that, from a statistical perspective, participation in adult education and training is mostly of a non-formal, job-related, and employer sponsored nature (fully or partly paid by the employers and/or taking place during paid working time). The adult participation rate in non-formal learning (36.8%) can be further broken down as follows: just a small 5.9% participated for non-job-related reasons, while 30.9% had job-related reasons for participating (at least once). Moreover, non-formal job-related learning is mostly supported by employers: 27.5% of adults in the EU participate in job-related learning activities with employer support (at least for one activity), and only 3.4% of adults participate with no employer support at all. According to Eurostat estimates, the average participation rate for Member States is 25% for employees of small enterprises [

3].

Based on these data, we formulated the following hypotheses regarding our study:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). There are no significant differences in terms of the attitude toward the process of professional training at the level of the three regions.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The management of the organizations encourages employees to participate in training programs. Over 25% of the organizations’ employees had participated in at least one training program in the past three years.

Courses are rather formalized, while “other forms of training”, which often occur at the immediate place of work, are sometimes difficult to distinguish from regular work and learning and therefore are less visible and more difficult to survey. According to Eurostat estimates, training incidence in the EU in 2010 is at 66%, with 56% of enterprises offering courses and 53% offering other forms of training. Regarding these data, we considered it appropriate to analyze the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). It is preferred to contract the services provided by third parties in terms of the organization of training programs. Over 50% of employers use the services of specialized enterprises.

According to Continuing Vocational Training Survey 4 estimates, training incidence in Romania has reached 16% in 2010, after being at 28% in 2005. The training incidence indicates the proportion of enterprises with training activities. To be classified as a training enterprise, the enterprise must finance fully or at least partly training that was planned in advance. The primary objective must be the acquisition of new competences or the development and improvement of existing competences [

3].

Based on these data, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). In over 25% of SMEs, there are sums allocated in the budget for the training and development of employees.

According to AES, in 2011, in the EU as a whole, it can be estimated that 11.8% of adults did not participate in education or training in the 12 months prior to the interview, but would have liked to have done so. Nevertheless, it is encouraging that in some countries with relatively low participation rates (Greece, Cyprus, Malta, and Romania), a substantial percentage of adults would like to participate [

3]. Additionally, considering the fact that our study considers three regions that have benefited from an European financing program, Joint Operational Program (JOP) RO–UA–MD, which have had the potential to increase the level of intention to participate in training and educational activities, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). The employees are aware of the competitive environment of the labor market, and at least 50% of them want to improve their skills and abilities by participating in at least one such program per calendar year.

In the EU on average, enterprises perceive customer handling, technical, practical, or job-related and teamwork skills as most important in the years to come. Problem solving and management skills are also rated as important by more than 40% of enterprises in the EU average in 2010. General IT skills also remain high on the agenda with roughly half of the enterprises considering them important. There are substantial cross-country differences, which also reflect differences in national contexts. There are considerable differences in the perceived importance of skills across Member States, which are also mirrored by the skills targeted by courses [

3]. Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). There are differences in training needs within the analyzed regions.

The core part of this paper is the discussion of the survey results and of the main findings regarding the perception that the employees of SMEs have with respect to the trainings of human resources and the need for future learning programs. These aspects are explained and placed in context. In Suceava, more than half of the respondents had participated in a training program in the last three years, and more than 50% of the organizations’ employees had participated in at least one training program in the last three years, while this is not the case for the Chernivtsi and Bălți regions. Over 25% of SMEs from Suceava and Chernivtsi allocate money for employee training programs, and the percentage is less for the Bălți region. The similarities are that, in the three regions, over 50% of the SMEs have used the services of specialized enterprises and the employees have wished to attend at least one training program per year.

The last section includes some recommendations formulated for the management of SMEs, with the hope that the suggestion formulated will improve the positive effects and the impact of training on the success of the companies. Additionally, the results are relevant for other categories of stakeholders in the regional planning of labor market development measures.

In this way, we studied a less analyzed aspect, which brings about the novelty of this research, thus succeeding in highlighting some differences regarding the attitude toward human resources training between some regions of a cross-border area in the context of the inclusion of one of them in the EU since 2007. The paper ends with conclusions to this research.

2. Challenges of SMEs in Transition Economies

SMEs are perceived as important contributors to national economies. The SMEs represent 99% of all businesses in the EU, with more than 20 million companies, and also influence economic growth, innovation, employment, and social integration [

4]. There is a common understanding in the EU of the definition of SMEs, according to the explanation given by EU Commission Recommendation 2003/361: “the category of SME covers the enterprises which employ fewer than 250 persons and which have an annual turnover not exceeding 50 million euro, and/or an annual balance sheet total not exceeding 43 million euro” [

5].

According to G. G. Culiță [

6], there are solid arguments for perceiving the contribution of SMEs to national economies as important: they generate the most part of GDP in each county (between 55–95%), they are creators of new workplaces, and they generate the most innovations applicable in the economy, one of the most important sources of contributions to local and national budgets.

Additionally, some weaknesses are not to be neglected: scarcity of resources and reserves; dependency of the company on only one person, in most cases, the entrepreneur; and instability and outdated technical endowments, as compared to larger companies. Despite criticism, SMEs are connected in many studies with economic growth [

7].

All countries taken into consideration for the current research have undergone similar socialist experiences. After a large-scale development of state-owned enterprise until 1990, the SMEs looked for a chance for transformation and progress. The further development of national economies is related to the healthy development of SMEs, but most companies from Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine were affected by the interaction with transition ideology [

8].

Disparities between the neighboring countries exist, as well as between different areas of the EU (North versus South, East versus West) and several EU programs and policies, from convergence and sectoral programs envisaged as support of SMEs from less developed areas. E. Paliginis [

9] assumed that the peripheral areas of the EU are more sensitive to failure, partially due to the lack of some pre-conditions such as a dynamic economy, clusters of industries, and centers of finance, research, and technology, despite having some advantages, such as cheap labor and national and regional support. Geographically, the European periphery includes those countries on the edge of the European Union; however, some relatively central European countries (e.g., Hungary) are considered “peripheral”, and it seems that countries can change their status from “core” to “peripheral”, in some sense [

10].

At the other corner of the former socialist block, in Serbia, entrepreneurship is also seen as a great opportunity [

11], but, at the same time, the authors admit that the contribution of SMEs to the employment rate and economic results is much smaller compared to the developed countries of the EU.

The SMEs sector carries great hopes and great burdens in the evolution of all transitional economies [

8]. Almost all authors acknowledge the role of SMEs in economic development and the need to support this sector, since the support and growth of SMEs determines a rise in the living standards. Why are the problems of SMEs still not tackled? Some authors suggest that a kind of auto-determinism mechanism will get into action, a “market automaticity” [

8]. The SMEs sector is more sensitive to external factors, such as legislation, technology, political changes, and others. Nicolescu and Nicolescu mention that most SMEs face big problems with the business environment [

12], the same idea being confirmed by Wieneke and Gries [

13], who have stated that the SMEs are facing obstacles generated by external environment, obstacles that were difficult to be solved by the “less experienced owners” [

14].

Additional to these, the internal environment could raise some problems for the entrepreneurs: pressure to adequately use the resources in order to gain market advantages and the appropriate motivation of human resources in order to obtain competitive advantages. The research of Mulliqi et al. [

15] shows that there are empirical findings showing that “human capital endowments have a significant effect on the international competitiveness of the Central and Eastern Europe countries”.

3. Human Resources Training and the Performance of SMEs in Transition Economies

According to McIntyre, enterprises, managers, and workers in urban and rural sectors are modern and “fit to survive” [

8]. For surviving, the personnel should have skills to adjust, interpersonal and technical skills. The role of the human resources in the performance of SMEs was mentioned in both the Romanian [

16] and foreign professional literature [

17,

18]. The recent research demonstrates that the human resources (HR) are the core asset of an enterprise, and the training of HR is connected with sustained growth in productivity. The importance and significance of employee training and development on the company results are confirmed by researchers worldwide [

2,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The HR training is defined as the application of formal processes to impart knowledge and help employees to acquire the skills necessary for them to perform their jobs satisfactorily [

25]. Employee training and education are of great significance for improving the overall quality of work and promoting the sustainable and healthy development of human resources [

2]. The training emerges as one of the key elements that may produce outcomes in terms of performance and suggests that the contribution clearly fits into the positive effect of investing in human capital [

26].

The connection between training of human resources and performance of SMEs was brought to attention again in recent years [

27]. A wide range of research papers shows a positive relationship between employees in company training and obtained returns, measured by return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE). The studies also demonstrate that an increased investment in training is linked to better employee behavior indicators, and the conducted studies provide evidence of the positive impact of training on employee loyalty to the company, thus showing that training diminishes employee turnover [

28].

Employee trainings directly impact the employee’s motivation and organizational performance [

29]. More than that, the training is, according to Caloghirou et al., connected with innovation [

30]. In the large organizations, the training of human resources (HR) is almost a tradition, but the situation is notably different in the SMEs. Being neglected in the SMEs, compared with other human resource management (HRM) functions, training is often perceived as an additional cost.

A research study undertaken in 2009 by WYG International [

31] in the UK, Poland, Turkey, and other countries, showed a low interest of SMEs in the training of human resources. The declared reasons were lack of money, misunderstanding of the role of training by the business owner, difficulties in leaving the workplace, costs of travelling, and lack of interesting training topics. Not all training programs were criticized: the exception was the training at the workplace. The same research [

31] has proposed a list of topics proposed for HRM trainings in SMEs. Most of them were a mix of practical skills and classical interpersonal competencies, also mentioned by other researchers: communication techniques, negotiations, leadership, employees’ career planning, employees’ performance management, team building, conflict management, key clients management, stress management, time management, decision making, change management, innovation, creative thinking, building and moderating organizations’ culture, and knowledge management [

32,

33].

The sustainability debate is present in the organizational environment and appears as an opportunity that shows the importance of including people as protagonists, keeping an ethical role for HRM due to its complexity [

34]. Sustainable HRM aims to extend the HRM theories, models, systems, and processes from that of a singular profit-based motivation to a three goal triple bottom line view including social and environmental outcomes [

35]. Sustainable HRM has a very broad manifestation area, creating multiple interferences. The implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in business organizations and the interconnection with all its subsystems, in particular with HR, has led to scientific interest materialized in an unprecedented elaboration of literature that interrelates CSR and HRM [

36]. Today, we believe that at the enterprise level, HRM must include a “sustainability” component. An organization that wants to practice sustainable HRM should aim at developing employees in sustainability, by involving them through task forces, trainings, and in the sustainability strategy’s elaboration and implementation [

37]. Sharing knowledge voluntarily seems to be a very important variable to take into consideration in a sustainable HRM as a desirable outcome of HRM sustainable policies [

38].

The importance of training of HR is more important in remote areas of transformation economies, where access to highly qualified employees could be difficult, due the high rate of internal and external migration. In the SMEs, the training of HR could have an important leverage effect, alone or combined with other HRM functions [

39].

Organization performance depends on the employees and on their knowledge and skills [

40]. In a different life-stage, the SMEs from the Eastern economies have different approaches and priorities from SMEs in Western economies. Moreover, the SMEs prove specificities when compared to large enterprises in terms of training and development needs [

40,

41].

A study by Slavic et al. [

42] shows that the companies from other former socialist countries that were analyzed (Croatia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Hungary) are performing systematic evaluation of training effectiveness and are using mostly on-the-job training and mentoring. The same authors are stating that “in general, organizations that have a more developed T&D approach are likely to have a higher level of performance” [

42].

Mulliqi et al. [

15] mention an increased interest in human resources training developed in the current period, compared with the period from the beginning of transition.

Only a few studies have approached the training of employees’ SMEs in the Eastern part of Europe. For this reason, the paper would contribute to the analyses that were done for other transition economies.

The HR training needs are analyzed from many points of view in numerous studies, however, quite few focus on the HR training needs perception. As a result of a survey-based study on HR training projects, Erina et al. show that for participants, the projects’ accordance with their own professional and personal interests is most important, while providers and managers focus on the application of acquired knowledge, developed skills, and changed attitudes in the workplace that might lead to a successful cooperation [

25]. Based on a survey, Lee et al. reveal that employees do not attach enough value to vocational training, and the authors consider that companies should supply more vocational training opportunities and support to employees, thus stimulating sustainable human resource development [

43]. In the education and training process, service quality is highly important, because it establishes satisfaction, trust, and motivation of participants, thus impacting their achievement [

44]. Most of the authors agree on the importance of HR training. Being a necessary part in the development of the organization, the human resources training is characterized by a clear strategic importance [

39].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Specificities of the Cross-Border Area Romania-Republic of Moldova–Ukraine

During the past few years, starting in 2007, the three areas/regions were included in the cross-border cooperation (CBC) region, in the framework of the Joint Operational Program, and became the space for implementation of joint projects in different fields, with the goal to increase the competitiveness of the neighboring countries of Romania, Ukraine, and Republic of Moldova (especially in border areas).

According to regional sciences approaches, the research area is considered a weak-integrated system, aiming to enrich the level of a semi-integrated system [

45]. K.-J. Lundquist and M. Trippl [

46] suggest solutions for moving forward in economic, social, cultural, and institutional fields.

The target region is characterized as a multi-peripheral territory. From the perspective of general economic theories, the territory is at the confluence of two main economic models, capitalist and socialist, the first one due to the proximity to the EU and the second one given by the proximity of the former USSR [

45,

47,

48]. As well, the three areas of the CBC region are parts of three national states, Romania, Ukraine, and the Republic of Moldova.

The European Commission considers cross-border cooperation as a key element of the EU policy toward its neighbors. It supports sustainable development along the EU’s external borders, helps reduce differences in living standards, and addresses common challenges across these borders [

49]. From the CBC area, we have selected three sub-regions, Suceava (Romania), the region of Chernivtsi (Ukraine), and the region of Bălți (Republic of Moldova), that are included in the Cross-Border-Cooperation Program (

Figure 1). The areas were selected due to the large number of development projects that were implemented in both 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 under the CBC Funding Program [

50]. For the period 2007–2013, we have the outlook of the program, the lessons learnt during implementation, as well as the most important achievements of the program through the ex-post evaluation of CBC programs’ final report.

For the Program Romania-Republic of Moldova, the EU financial allocation is EUR 81 million and the area includes Botoșani, Iași, Vaslui, Galați (Romanian counties), and Republic of Moldova—the whole country [

52]. In the implementation period 2007–2013, the number of Joint Operational Programs (JOP) RO–UA–MD awarded projects were 86 to Romania, 24 to Ukraine, and 30 to Republic of Moldova [

53], and the targeted areas included education and culture, transport, tourism, agriculture, economic development, energy, and quality of life [

54].

As Babinska stated [

55], the model of growth triangle was minted to bring economic growth, similar to other regions worldwide, as a “philosophy of cooperation and mutual understanding between the partner countries (…) based on the partner countries’ interest in socio-economic development and stability”.

As common features, all three areas had similar economic history, belonging to formal socialist countries. At the periphery of the EU, the cross-border area is facing similar problems today: weak infrastructure, lack of major investments, high rate of depopulation in the rural areas, high rates of migration, brain-drain to larger cities in the countries or to other more developed countries within EU, shadow economy, high level of unemployment, and increasing inflation [

55].

4.2. Research Problem and Research Objectives

Even though the knowledge related to the training and development of human resources is quite broad [

56], only limited empirical research was generated on the topic of human resources management in transition economies.

Without neglecting the common features of the areas of this cross-border region of the EU, we are acknowledging some differences, mainly to the different statutes of member/non-members of the EU. We also must underline that, at the economic level, the three regions are connected to some extent, and the cooperation, reciprocal knowledge, and respect have improved since the CBC program started.

The research question is whether countries coming from a common past (socialism) and that are part of the same cross-border region show different paths considering the inclusion of one of them in the EU since 2007. This aspect is investigated in the article by focusing on the specific training of SMEs that could be conceptualized as an indicator of economic dynamism.

The study is an exploratory one, and the survey was based on a semi-structured questionnaire applied to 320 respondents from the RO–MD–UA cross-border region. In addition to the presented research goals, we intended to analyze the differences among the neighboring countries from the cross-border cooperation (CBC) area.

The first part of the questionnaire included questions regarding the recent history of training and development activities carried out at the level of the company and of the employee, respectively. The second part of the questionnaire investigates future training needs and how the training sessions are to be conducted. The last part of the questionnaire included questions for identifying and classifying the respondents.

For the registered data, we used statistical instruments, and the outputs were generated with the SPSS software. In the survey, we have applied the questionnaire in print and online, in the above-mentioned regions: Suceava (Romania), Chernivtsi (Ukraine), and Bălți (Republic of Moldova) (

Figure 1).

The survey was made simultaneously in the three regions mentioned, using the database developed in a CBC project (developed in the framework Joint Operational Program Romania–Ukraine–Republic of Moldova) “Joint Business Support Center for the Development of Entrepreneurship in the RO–UA–MD Border Region” (JoBS), which supported specific actions for strengthening the business environment of the border regions, by promoting economic partnerships among the SMEs in the cross-border region.

The research aim was to identify the training needs of entrepreneurs and employees within SMEs from the Suceava, Chernivtsi, and Bălți regions, to analyze the specific training practices in cross-border area, and to identify the common features or the disparities: the attitude of management and employees toward the professional training, perception of long-life training, participation to training programs in the recent period, type of organized trainings, cooperation with training providers, financial support for training measures, and the periodicity of training programs delivered to the employees.

We have taken into consideration the perception of the entrepreneurs but also of the employees of the SMEs as the main stakeholders involved in the training process. The analysis of the perception of HR of different types of trainings was planned according to the suggestion made by Zhang et al. [

2]. They have suggested the need for investigation of multiple companies, previous research being “mainly focused on a single enterprise, neglecting the perspective on multiple enterprises” [

2]. We followed as well the opinion of Erina et al. [

25], who identified differences in the way that the participants, training providers, and managers are valuing the results of training programs. The same authors have admitted that the perception of the employees is highly influenced by their own personal interest, additional to the professional one. For a positive impact of training, the goals of individuals should be considered and are important, additional to the organizational goals envisaged by the companies [

57].

The specific objectives of the research are aligned to the research hypotheses.

4.3. Description of the Research Sample

The analyzed statistical population sample consisted of the total of the SMEs registered in the above-mentioned regions. In 2017, according to the official statistics, 12,195 SMEs were registered in Suceava county [

58], 3925 in the Chernivtsi region [

59], and 2550 in the Bălți municipality [

60]. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS and RStudio, and all the outputs (tables and figures) were generated with these software packages.

If we take into consideration the heterogeneity of the statistical population, the differences in terms of the organizational and entrepreneurial culture of the subjects from the three regions, and the difficulty of motivating the subjects to participate in such a research study, the selected research method was the exploratory survey. Therefore, the statistical representativeness was not the main focus, but rather the possibility to obtain more detailed information regarding the training needs of entrepreneurs and employees within SMEs from the Suceava, Chernivtsi, and Bălți regions, which can subsequently allow for the development of research oriented toward specific sectors of activity.

For this exploratory research, we aimed to interview at least 100 respondents from each region and for at least 50% of them to be employed in executive positions.

The observation unit consisted of the representative of the economic organization who was either fulfilling the status of an entrepreneur or the status of an employee with an executive function from that enterprise (

Table 1).

The representatives of these economic organizations have been interviewed using an online questionnaire particularized/customized according to the two qualities mentioned before. The semi-structured questionnaires consisted of closed type questions and also open response questions so that we could obtain as many details as possible related to the investigated theme.

The questionnaires included eight questions that investigated the history of the training activities carried out by the organization and other eight questions investigated the vision for the future of the organization regarding employee training. At the end, there were six questions that allowed us to obtain details that described the specificities of the organization and the demographic aspects of the respondent.

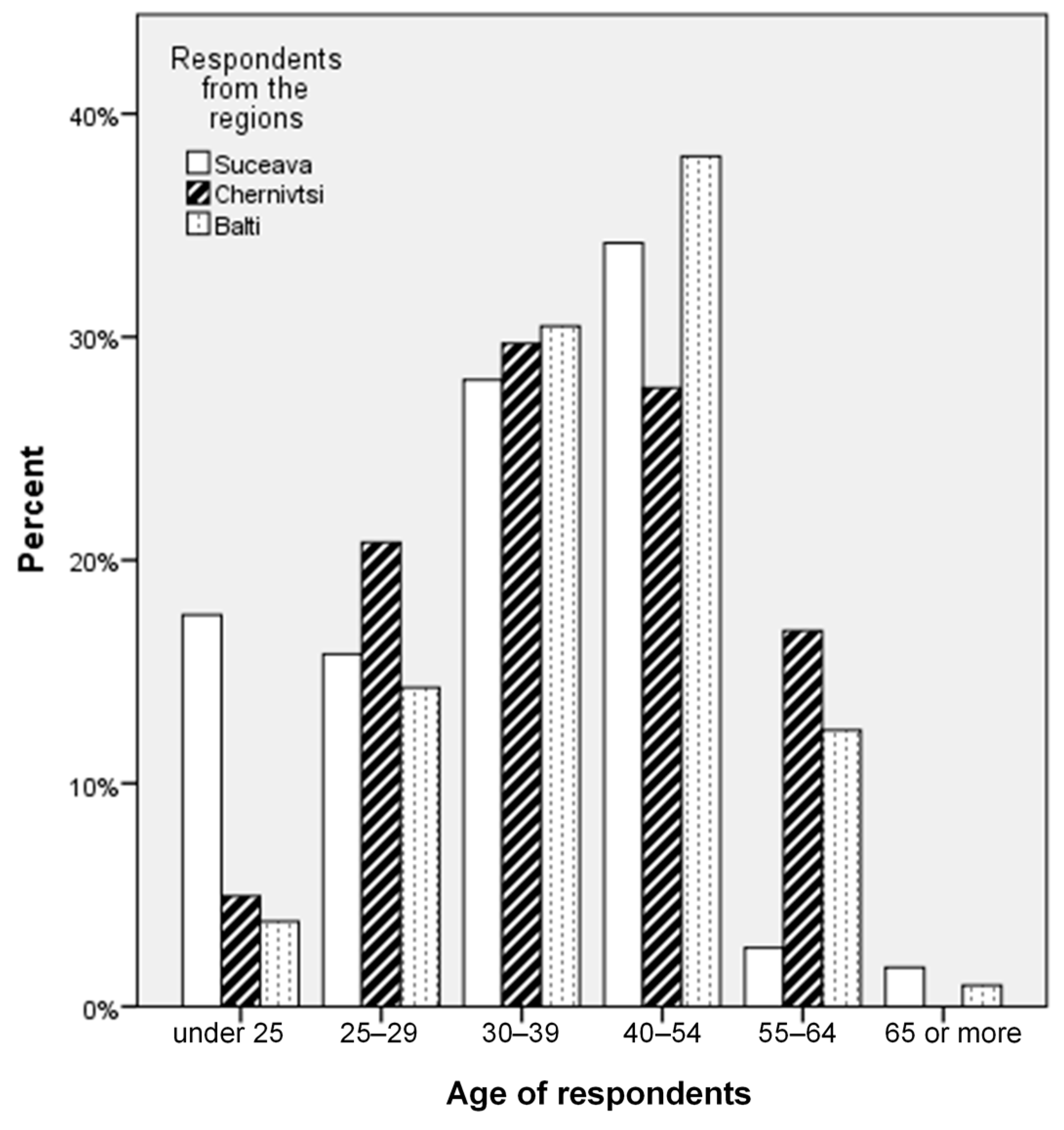

The respondents were mainly people aged between 30–54 years and with seniority in the organization of maximum 10 years (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

We wanted to include in the sample mainly people who had not acquired a large number of years of seniority, with the idea that these are the ones who want to gain knowledge and new skills, allowing them to consolidate their career.

The characterization of the respondents in terms of their graduated studies emphasizes an orientation of the employees toward higher education studies, as 90% of the respondents were found in the three university cycles (

Table 2).

From this perspective, we have considered that an approach mainly of university graduates will facilitate the acquisition of relevant information in terms of human resources training and development within SMEs from this cross-border area.

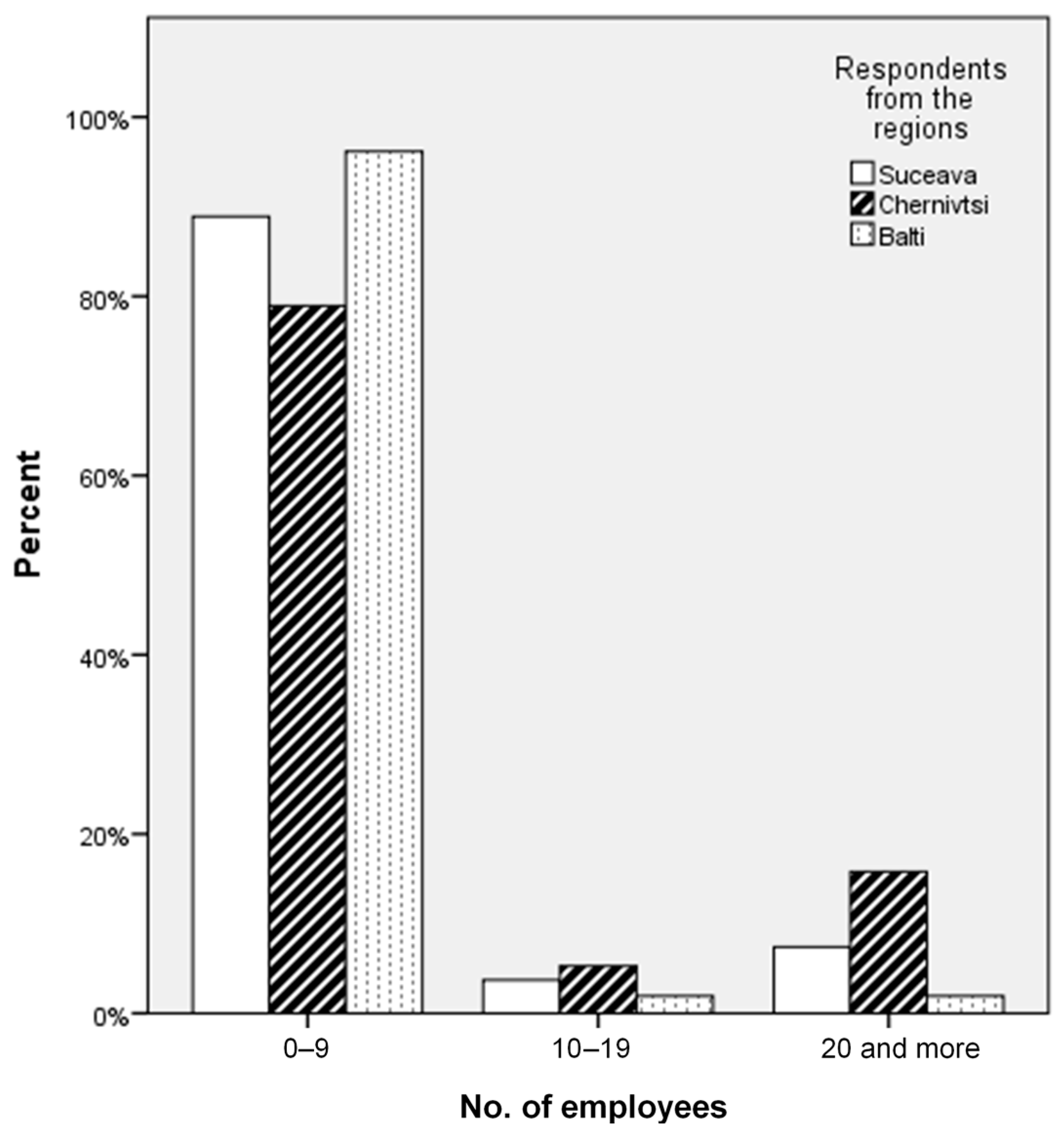

The analyzed samples in the three regions comprised up to 90% of enterprises from the micro-enterprises category and from the small enterprises category, thus maintaining the existing proportion at the level of the general population as well (

Table 3).

The widest possible coverage in the area of the activity sectors has been attempted; however, the great majority of the economic organizations belong to sectors such as trade, transport, hotels and restaurants, industry, and services, such as professional, scientific, and technical activities (

Table 4).

4.4. Methods of Processing and Evaluating Hypotheses

For the analysis of the research hypotheses, we used a series of statistical methods, adequate to the specifics of the research.

To highlight whether there are statistically significant differences among the three groups of respondents related to the three regions included in our analysis, we used a Pearson Chi-Square Test. The Pearson’s χ2 test (after Karl Pearson, 1900) is the most commonly used test for the difference in distribution of categorical variables between two or more independent groups.

In the analysis of the hypotheses set for the research, we also used a one sample t-test. The one sample t-test is a statistical procedure used to determine whether a sample of observations could have been generated by a process with a specific mean.

In order to synthesize the data collected and identify appropriate training packages, accepted by the economic operators investigated, we considered it useful to use multiple correspondence analysis (MCA). Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used to analyze categorical data and transform them into clusters where the results can be represented in a graphical manner.

MCA enables relationships between both row and column variables, as well as between different levels of each variable, to be investigated [

61]. MCA is particularly useful when analyzing more than two categorical variables and is used to detect and represent underlying structures in a dataset in a low-dimensional Euclidean space. Therefore, it is unique in describing the patterns geometrically by locating each variable as a point in a low-dimensional space and the variables distributed along the dimensions. The closer the distance between points represented in space, the more similar in distribution the categories become [

61].

5. Results and Discussion

The report’s interpretation based on the received answers indicates the existence of a significant differentiation from a statistical point of view in terms of the manifested attitude toward the professional training process after the moment of completion of an educational cycle that allowed for the acquisition of a qualification (

Table 5).

Whereas Suceava county employees and entrepreneurs unanimously agree that the training process has to continue throughout life as a professional training process, in the Chernivtsi and Bălți regions, we have received contradicting opinions and also situations of indecision (17.8% and 20%, respectively) (

Table 6).

Additionally, responses to the question “Have you participated in training programs in the past three years?” indicate a differentiation between the three regions. In Suceava County, the proportion of those who participated in training programs in the past three years exceeds the one of those who did not participate, whereas in the case of the Chernivtsi and Bălți regions, the proportions are inverted. In the case of the Bălți region, a large discrepancy can be noticed between the proportion of those who participated—28.3% and the proportion of those who did not participate—71.7% (

Table 7).

Therefore, overall, the three regions differ from each other in terms of the manifested attitude toward the professional training programs. Thus, we can conclude that hypothesis H1 cannot be confirmed.

The open question related to the courses taken by employees in training programs highlighted, as expected, a very wide range of topics (

Table 8).

In the attempt to synthesize the information, it can be pointed out that, in the three regions, the employees of the analyzed organizations participated in economic and business administration courses, in most cases.

The analysis of the differences between the average rates of participation in training programs for employees from organizations in the three regions and the value projected in hypothesis H2 points out that in Suceava and Chernivtsi regions, the difference is not significant, and, in the case of the Bălți region, a figure under the tested value can be noticed, and this difference is statistically significant (

Table 9,

Figure 4).

Therefore, we can conclude that the hypothesis H2 is invalidated in all investigated regions.

As far as hypothesis H3 is concerned, it has been observed that in all the three regions, the organizations mainly resort to external providers for training and staff development services (

Table 10,

Figure 5).

In all the three cases, the 50% percentage has been significantly exceeded in terms of contracting services from external providers. Therefore we can conclude that, in the three regions, the hypothesis H3 is confirmed.

In terms of information sources for the selection of training providers, the management structures of organizations in the Suceava region prefer collaborators (customers, suppliers) and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry. In the Chernivtsi region, a difference can be noticed, in the sense that the firms from this region prefer to get informed through the media and specialized NGOs. In the Bălți region, there is a preference for information through specialized NGOs and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry (

Table 11).

In terms of the effectiveness of the training programs, our survey showed that only in the Suceava region, there is a significant percentage (81.5%) of those who succeeded in transposing into current activities the knowledge gained within the training sessions. In the other two regions, the percentage of non-implemented gained knowledge is higher (over 50%) than the percentage of implemented knowledge (

Table 12).

This fact raises a question regarding the adjustment of the offers from specialized companies to the market needs, but also in terms of identifying the real needs of training of the employees. Additionally, the bad habit of simply acquiring a diploma seems to persist among training participants, as well as the fact that they are dismissive of the factor of whether the perfected skills could be put into practice in the workplace.

The answers to the question “Which are the reasons that motivated you to participate in training courses?” are somewhat in contradiction with the facts emphasized above. Most employees in all three regions (90% in Suceava, 78% in Chernivtsi, and 64.2% in Bălți) responded that they participate in training programs due to the need to update/complete the information needed to perform duties within the organization they work in (

Table 13). Another important share is represented by those who participated in training courses due to the need for certification of existing knowledge.

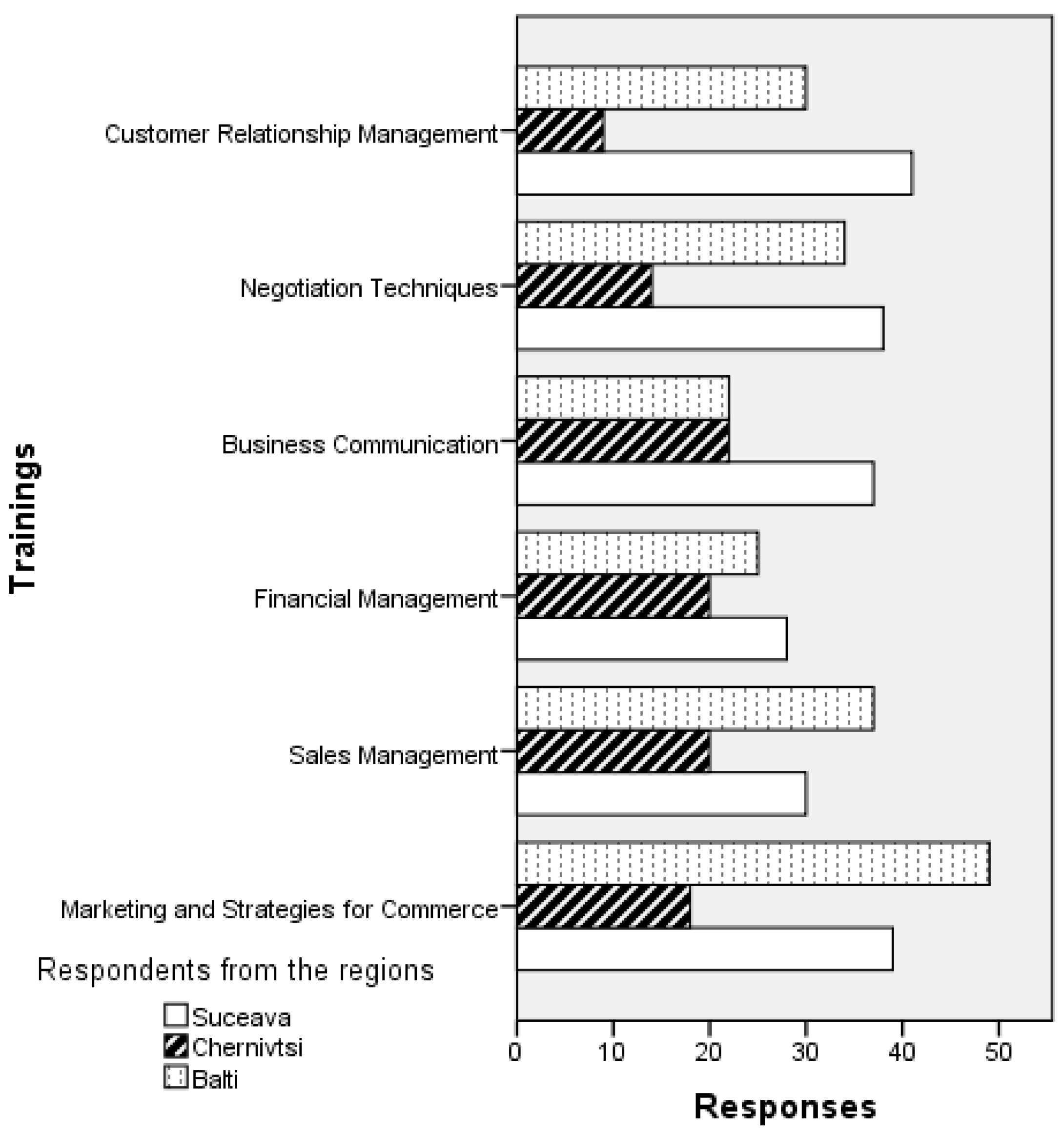

In terms of future courses in business administration, the respondents’ preferences were directed toward issues concerning customer relations techniques and financial reporting techniques (

Figure 6).

Given that 90% of the organizations in the sample are micro and small enterprises, respectively, the availability to include up to nine employees in training programs indicates a clear orientation toward the need for improvement and acquisition of new knowledge in the employees’ fields of activity (

Figure 7).

The targeted abilities by respondents are quite numerous, but they fall within the management of relations with employees and customers, crisis management, or rapid adaptability to changes in the working environment (

Table 14).

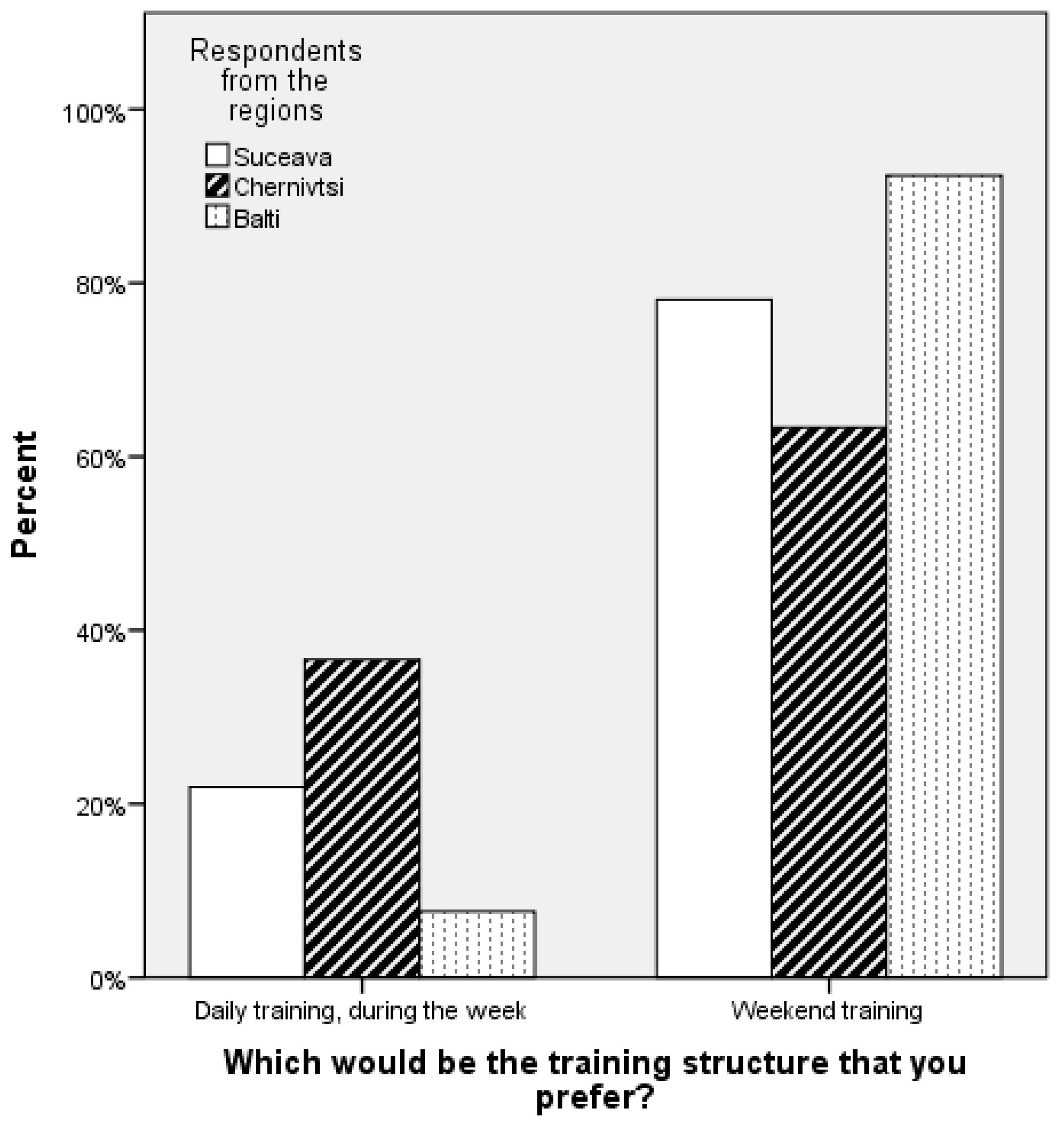

From the point of view of the organization, most of the respondents prefer that the training programs be carried out in a single session during a calendar month for which the courses could be scheduled at the end of the week (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

In terms of the delivering process of the training courses, the answers are relatively similar in the three regions, interactive training sessions and discussions on some relevant examples for the topic being preferred (

Figure 10).

The values presented in the previous figure represent the averages of the distribution of the number of course hours for each type of training session organization.

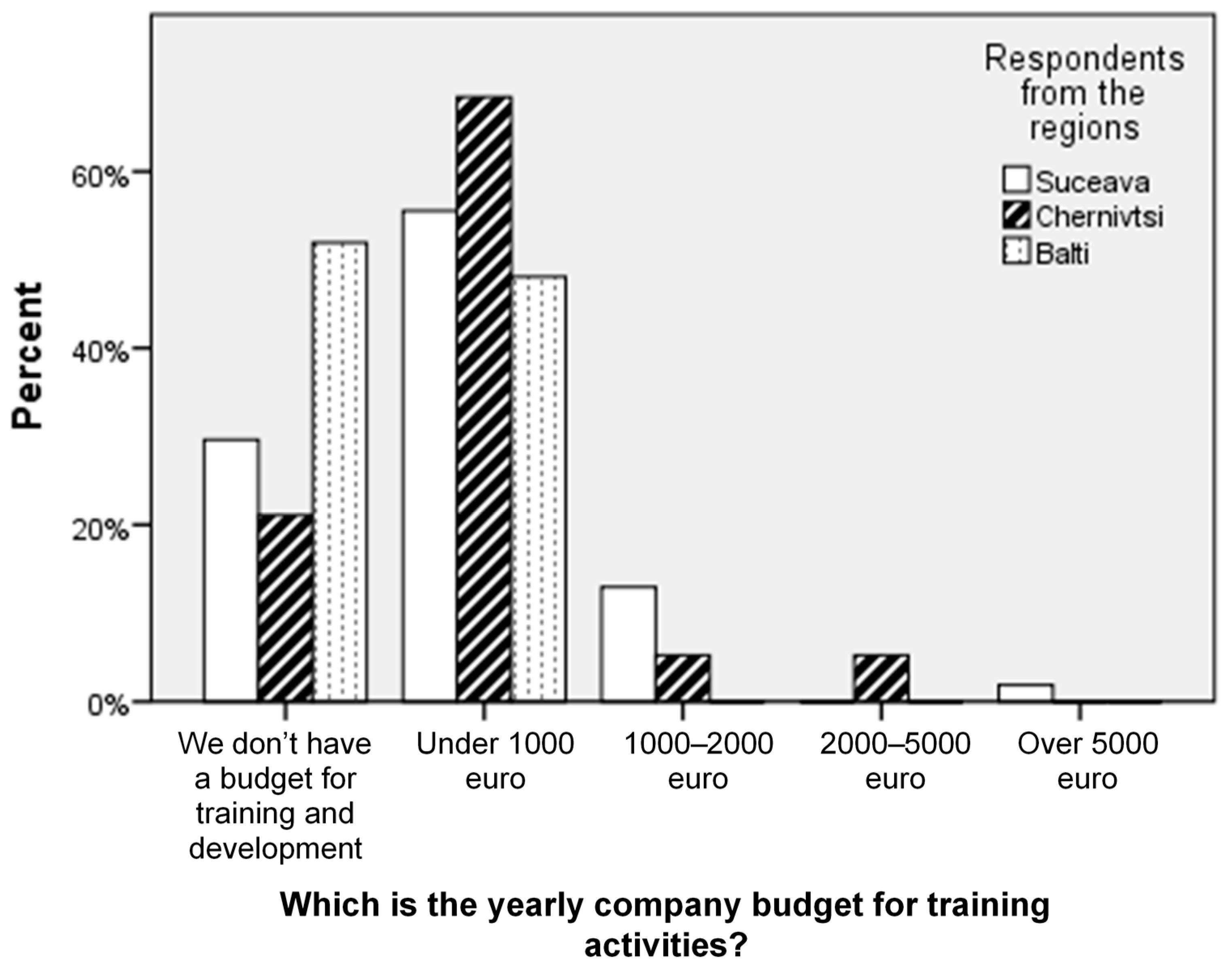

The analysis of the percentages associated with the organizations that allocate budget resources for employee training programs emphasizes that, in the Suceava and Chernivtsi regions, at least half of the organizations included in the sample make such budget allocations (

Table 15,

Figure 11).

Thus, hypothesis H4 is confirmed in the cases of Suceava and Chernivtsi and invalidated in the case of the Bălți region. Overall annual allocations amount to less than €1000.

According to the received responses in all three regions under analysis, percentages significantly greater than the tested value of 50% of the number of employees who wish to attend at least one training program during a calendar year can be noticed (

Table 16). Thus, we can confirm the H5 hypothesis in all three regions.

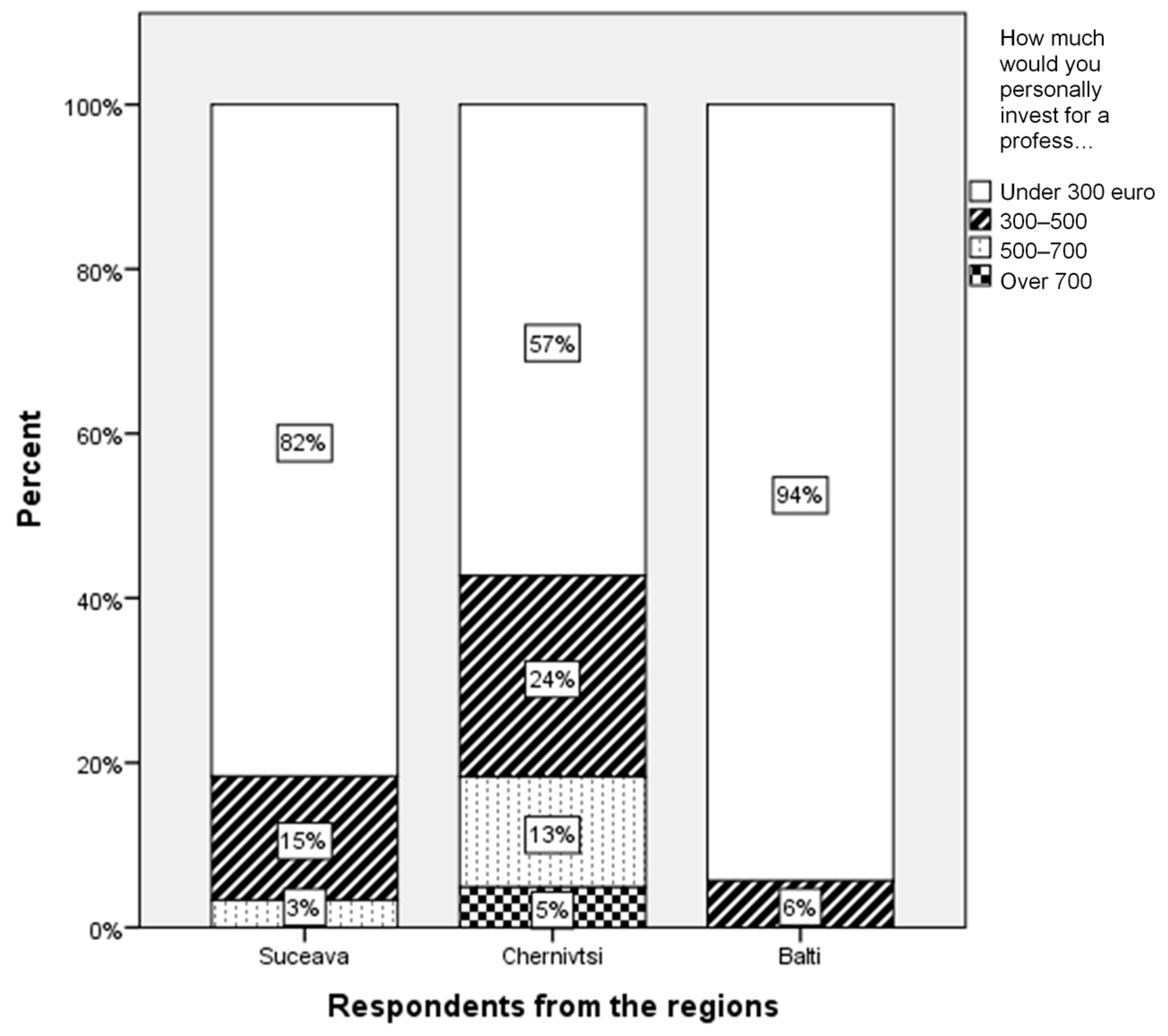

If they were to invest personally in participating in such a program, the budget that the majority of employees would allocate would be of maximum €300 (82% in Suceava, 57% in Chernivtsi, and 94% in Bălți). Compared to the other regions analyzed, in the Chernivtsi region, a significantly higher proportion (24%) of those who would be willing to pay up to €500 could be identified (

Figure 12).

Among the priority fields of the employees, in terms of their development/improvement in the following calendar year, the following could be identified with a relatively high frequency: accounting, business communication, risk management, and agriculture (

Table 17).

A percentage of approximately 30% of the respondents expressed their willingness to participate in courses whose topics are not within the current scope of competence (

Table 18).

The topics presented in the above table are very different, but it can be seen that the predominant ones are related to the economic field.

In conclusion, we can state that, for all the three regions, the employees are aware of the competitive environment from the labor market, and they want to improve their skills and abilities by participating in at least one such program per calendar year. Therefore, we can state that the hypothesis H5 is confirmed for all the three regions.

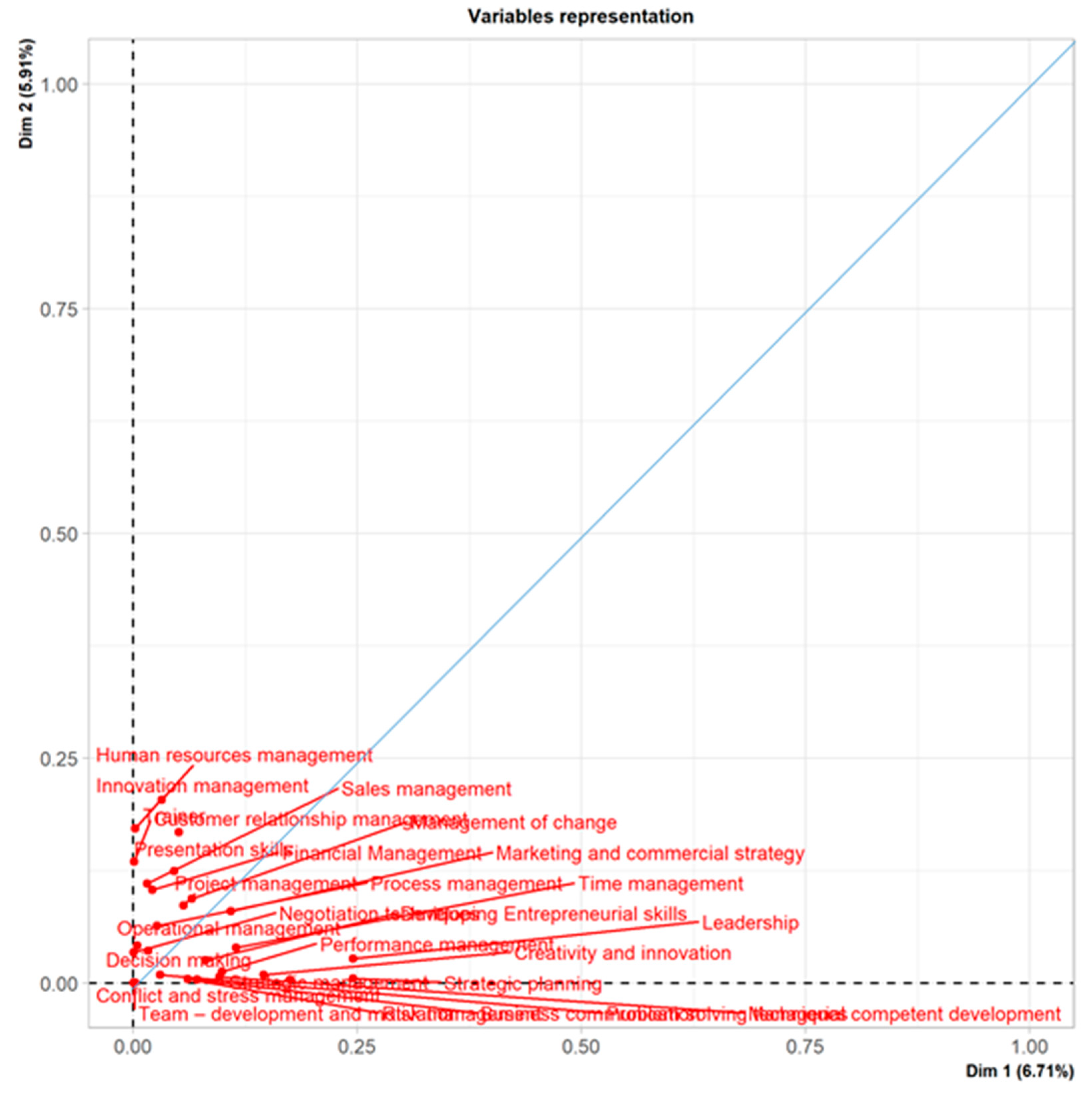

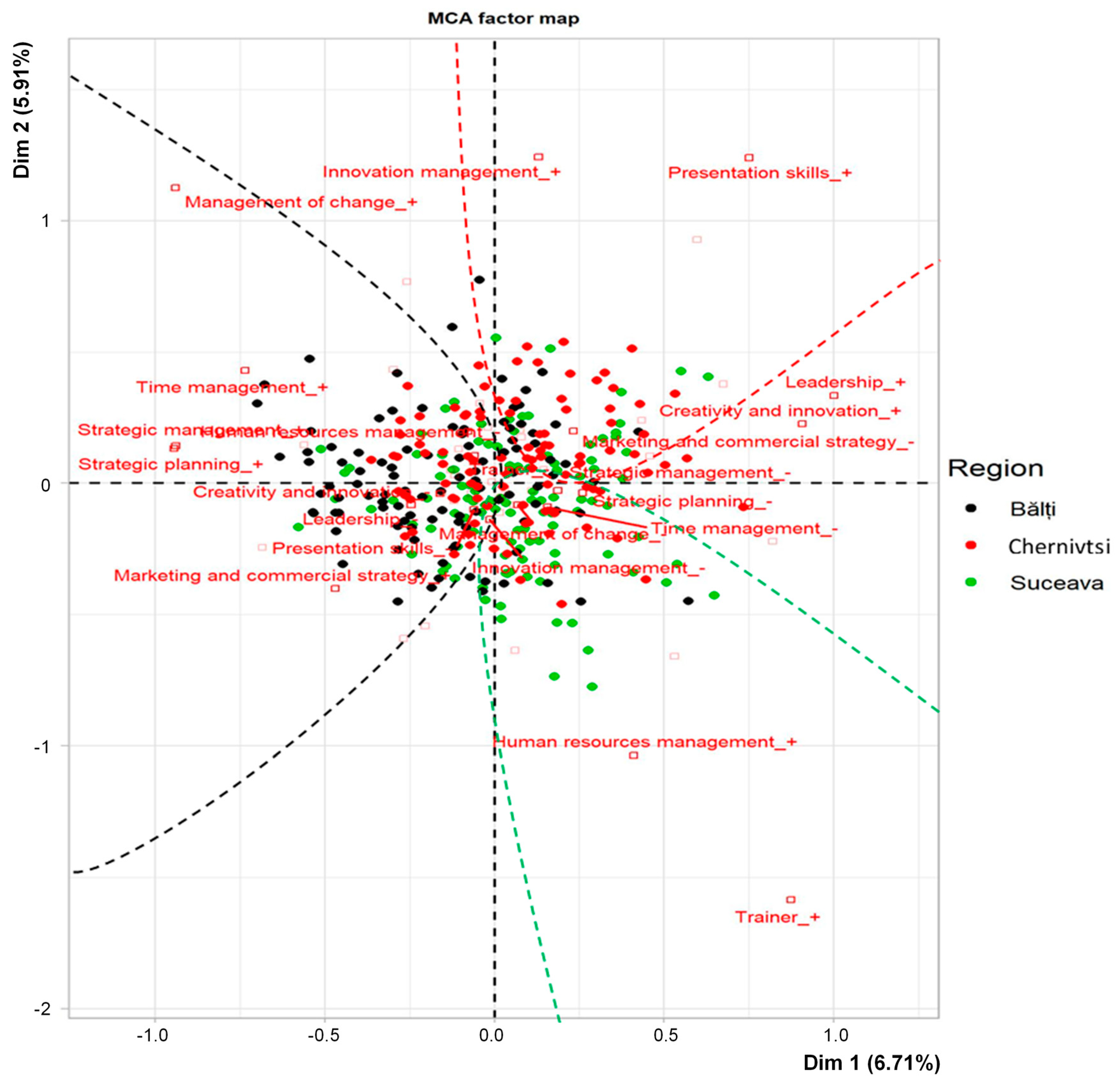

In order to synthesize the data collected and identify appropriate training packages accepted by the economic operators investigated, we considered it useful to use multiple correspondence analysis (MCA).

The variables representing the lecture suggestions have been subjected to the investigation. A two-dimension MCA solution was considered in the analysis, where the first and second dimensions, respectively, have the following features: eigenvalues 0.07 and 0.06 inertia, 6.7% and 5.9%.

The MCA map shows respondents in principal and categories in standard coordinates. MCA minimizes the sum of squared distances between category points and respondents. For each variable, a discrimination measure (

Appendix A), which can be regarded as a squared component loading, is computed for each dimension. This measure is also the variance of the quantified variable in that dimension. A maximum value of 1 is achieved if the object scores fall into mutually exclusive groups and all object scores within a category are identical.

The perceptual map generated by MCA is illustrated in

Figure 13. The percentage of variance explained by each attribute can be used to interpret both dimensions. The farther an attribute is from zero in a given dimension, the more important that attribute is in explaining that dimension.

The first dimension, “innovation and training”, is the vertical dimension of the plane; innovation management and trainer are far from zero in this dimension and are therefore the most important aspects.

The horizontal dimension “leadership and planning” has leadership as its highest point and strategic planning as its lowest point.

From the MCA factor map analysis, we can identify a tendency to associate the groups of respondents, from the investigated regions, toward with different training proposals. Respondents from the Balti region seem to be interested in trainings in the fields of strategic management and strategic planning. Even if in the case of the respondents from the Suceava and Chernivtsi regions, the delimitation of the fields of interest is not obvious, a tendency can be identified for the respondents from Suceava toward human resources management and trainer, and for those from Chernivtsi toward innovation management and presentation skills. Concluding, the MCA allowed the identification of some differences regarding the orientation of the respondents from the groups toward different training proposals, which allows us to confirm the hypothesis H6 of the study.

The research of training packages selected by respondents suggests the orientation toward an autocratic management style and a well-structured command function, with a clear distribution of leading responsibility, placed at the top of the companies. Moreover, the less preferred training fields suggest that the existing management style is not necessarily associated with participative management, empowerment, and team-based decision culture.

It is difficult to find success recipes for SMEs in a challenging world. The Stiglitz approach appears to be still correct [

8], now, many years later. In the future, the SMEs should ensure a better use of human and financial resources, as well as a better use of opportunities [

62]. The general tendency of SMEs is to focus on administrative functions of human resources: staffing and payment, mostly. It is important for SMEs management to acknowledge that at the beginning of the 21st century, with dizzying development of information and communication technologies, the human element became the single one that the competition could not copy [

11] (p. 73).

The results of the research could deliver some relevant insights for the managers of SMEs from the target area. For a positive impact of training, the goals of individuals should be considered. The trainers and the management should try to harmonize, in the training planning stage, the organizational training goals, with the interests of the employees. That could increase the motivation of participants to attend. The suggestion is also confirmed by other papers that have stated that the interest of employees is highly important, additional to the organizational goals envisaged by the companies [

57]. The participation in training has an important leverage effect in what concerns the motivation of human resources. A yearly training package that is delivered to the employees could contribute to their self-fulfillment and improve their loyalty toward the company.

Undoubtedly, there is an increased interest in human resources training in the current period [

15]. Stofkova and Sukalova pointed out the importance of human resources training and examined the perception of the impact of employees’ skill development on their performance [

63]. As a result of our survey in a cross-border region, we can underline that it confirms the importance of HR training. Erina et al. [

25] showed the motivation of both employers and employees, while Budiyanti et al. underline the necessity of service quality [

44]. We found that the content of training should be fit to the company’s needs, so that the employee can use the acquired knowledge at his job.

The training could be conducted both in-house and externally. It is possible to bring in a trainer to train several employees on the same subject matter, but then employees could be sent to an off-site training. In the analyzed area, in general, the companies do not have the subject matter expertise within human resources, a training department, or another department to conduct the training. If the situation imposes it (public health), or due to some other reasons (distance, time, expenses), the training can be conducted online.

If the SMEs are working mainly with external consulting companies, they can reduce the costs of implementing trainings while achieving the goals of training through the shared trainings. The proposal is in congruence with the suggestions made by Zhang et al. [

2]. They are admitting that the “shared trainings” have as an advantage the exchange of knowledge among SMEs employees.

Another important insight is related to the role of the Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CCIs). In all three analyzed areas, the credibility of CCIs is high. CCIs could organize joined training programs or could conduct further research on the training needs of SMEs. Additionally, CCIs could further play the role of mediator between SMEs and training companies.

6. Conclusions

The main objective of the study consists of the analysis of the professional training needs for the SMEs from Suceava–Chernivtsi–Bălți regions. In order to get a clearer and more detailed picture of this topic, some specific aspects have been investigated.

They generally refer to the human resources development and adaptation to the changes specific to the economic restructuring process from Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine; the main factors of influence (both encouraging and blocking) the participation to professional training programs; the employees’ access to professional training opportunities; and the characteristics of professional training programs meeting the qualification needs on the labor market.

In Romania, rather large and diverse training needs for different economic sectors and for different occupations and companies were covered by the European Social Fund in the period 2007–2013. For this reason (among others), the training need is not as obvious in declarations as it is for the other two countries. The differences could be observed in the selection of courses/subjects, as well: if in Suceava, the courses were more technical and tasks-oriented (work inspector, quality inspector, manager for transport activities), in the Chernivtsi and Bălți areas, the suggested courses were more like general study fields (branding, accounting, marketing and sales, business administration). These differences in this approach could be interpreted as a clear identification of the training needs in the Suceava area, when compared to the areas of Bălți and Chernivtsi, where the indicated training fields are more generally described.

The results of our research are relevant for policy-makers, especially in making further decisions for the future cross-border financed programs.

The training is an investment, and for this reason, the expenditure should be justified by concrete results, reflected in an improved work process within SMEs. Therefore, following the explanations given above, a better identification of training needs in both Bălți and Chernivtsi areas is recommended, a better consultation of the SMEs’ management with the employees, and the identification of actual weaknesses and of the gaps that could be corrected through internal or external trainings, at the international and emerging market entrepreneurship in the cross-border area.

Moreover, for most of the SMEs, the training of human resources is not necessarily a priority. The numbers correlated with the participation in training programs in the past three years show a low participation in Chernivtsi (37.8%) and Bălți (28.3%), as compared to the Suceava area, with 53.3%. This number does not necessarily prove a better attitude of entrepreneurs from Romania toward the training of human resources, but the results of several projects in the training sector, developed and implemented with the support of ESF EU program.

However, there is room for improvement, with differences that should be covered in time: 46.7% of the employees from the questioned companies from Romania, 62.2% from the Chernivtsi area, and 71.7% from the Bălți area have not attended trainings in the past three years.

One of the limitations of the study is represented by the relative reduced number of participants to the analyzed sample. The volume of the sample does not ensure the statistical representativeness of the estimated indicators. Thus, it is necessary for this study to be continued, starting from the results of the exploratory research carried out, but extending the volume of the sample included in the study.

Another limitation is that the study is not connecting all stakeholders relevant for training of SMEs’ employees. This research is focused on the demand-side analysis, this being very important as a starting point for the training providers, in order to adapt their offer to the market. A future aim will be to analyze and correlate the opinions of our respondents (employees and managers) with the training providers, NGOs, and regional administrative bodies relevant for the labor market of all three regions.

In the future, human resources will continue to bring competitive advantage to the companies, big or small. It is desirable to understand properly the importance of the training for improving the skills, knowledge, and motivation of the people working in the SMEs. The research findings will contribute as well to the development of future training programs in the cross-border area, with EU support or through the partnerships initiated by the CBC program, in this remote area at the periphery of the EU.