Abstract

In Uganda, the agricultural sector contributes substantially to gross domestic product. Although the involvement of Ugandan women in this sector is extensive, female farmers face significant obstacles, caused by gendering that impedes their ability to expand their family business and to generate incomes. Gender refers to social or cultural categories by which women–men relationships are conceived. In this study, we aim to investigate how gendering influences the development of business relationships in the Ugandan agricultural sector. To do so, we employed a qualitative–inductive methodology to collect unique data on the rice and cassava sectors. Our findings reveal at first that, in the agricultural sector in Uganda, inter-organization business relationships (i.e., between non-family actors) are mostly developed by and between men, whereas intra-organization business relationships with family members are mostly developed by women. We learn that gendering impedes women from developing inter-organization business relationships. Impediments for female farmers include their restricted mobility, the lack of trust by men, their limited freedom in communication, household duties, and responsibilities for farming activities up until sales. Our findings also reveal that these impediments to developing inter-organization business relationships prevent female farmers from being empowered and from attainting economic benefits for the family business. In this context, the results of our study show that grouping in small-scale cooperatives offers female farmers an opportunity to overcome gender inequality and to become economically emancipated. Thanks to these cooperatives, women can develop inter-organization relationships with men and other women and gain easier access to financial resources. Small-scale cooperatives can alter gendering in the long run, in favor of more gender equality and less marginalization of women. Our study responds to calls for more research on the informal economy in developing countries and brings further understanding to the effect of gendering in the Ugandan agricultural sector. We propose a theoretical framework with eight propositions bridging gendering, business relationship development, and empowerment and economic benefits. Our framework serves as a springboard for policy implications aimed at fostering gender equality in informal sectors in developing countries.

1. Introduction

The global agricultural sector provides many people with employment and contributes substantially to economic growth. In 2014, the sector accounted for one third of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) (World Bank, 2016). In sub-Saharan Africa, this contribution corresponds to approximately 75% of employment. In Uganda in particular, the agricultural sector contributes 40% of GDP and 85% of export revenues, and it provides 80% of the total employment. Interestingly, in the Western economy, the agricultural sector is seen as a male-dominated sector, but in developing countries, women represent the majority of the workforce (NEPAD. Feeding Africa and the World. Agriculture in Africa: Transformation and Outlook. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/pubs/2013africanagricultures.pdf [accessed on 29 December 2020]). In Uganda, women’s contribution to the agricultural sector is notably greater than men’s. In the rice district, Bugiri—the main site for this study—women devote close to 75% of their time to rice production as opposed to 54% of men’s time [1].

Despite the key involvement of women in the agricultural sector in Uganda, female farmers face significant obstacles in accessing agricultural and commodity markets to sell their products and in accessing capital to raise the incomes and productivity of their family farming business [2,3]. Such access, however, is essential for women’s own ability to expand businesses—for example, producing and selling products in local markets—and to generate incomes. Obstacles are mainly caused by gendering. Gender describes the social or cultural categories by which relationships between the sexes are conceived [4,5,6]. Gender differences leave their mark on any social situation in which both sexes are present [7]. West and Zimmerman (1987, p.137) describe this act of “creating differences between girls and boys and women and men, differences that are not natural, essential, or biological” as “doing gender” [6]. Martin (2003, 2006) describes this same act as “practicing gender” [8,9]. Although the influence of gendering is becoming less apparent in Western countries as women’s economic position has improved over time, gender inequality remains present in the informal economy in developing countries [10]. In particular, barriers to women’s farming in sub-Saharan Africa are considerable and encompass gender bias and its impact on access to land, technology, and finance [11,12,13]. Women are disadvantaged, and this impedes their opportunities for empowerment and material well-being [1], although empowerment of women has been recognized as a critical driver of economic development in developing countries [14,15].

In this study, we aim to explore the influence of gendering on female farmers’ ability to develop business relationships and to overcome gender inequality. Business relationships between actors of different organizations are critical to business expansion overall. They enable these actors to attain resources, to achieve economies of scale, and to learn. Our study endeavors to examine how gendering affects the ability of women—key contributors to the agricultural sector and, hence, the economic development of Uganda—to develop business relationships with other actors in the farming value chain (i.e., dealers selling inputs such as seeds and fertilizers to farmers, buyers, millers, governmental entities, and famers). Relationships between local producers and local market vendors are, for instance, determinant for the overall value chain productivity and the economic position of its incumbents [16,17]. Our research question therefore is: how does gendering influence business relationship development in the agricultural sector in Uganda?

To address this question, we employed a qualitative–inductive methodology based on semi-structured interviews, focus groups, group conversations, a factory visit, observational notes, and photographs. Our aim was to capture the difficulties that female farmers encounter in expanding their family farming business, and to find out whether these difficulties are caused by gendering. Difficulties associated with collecting data in the informal economy are considerable and make our study insightful. Despite the key role of the informal economy in developing countries, research on wealth and income generation through the informal economy remains relatively scant [18,19,20,21]. In order to understand the unique research context and to enable data collection, we undertook qualitative research [22] in collaboration with an applied research project named Agri-Quest, which was supported by the Dutch National Science Foundation and located at Makerere University, a large public university in Kampala (https://knowledge4food.net/research-project/arf2-agri-quest-uganda/ [accessed on 29 December 2020]). Our main contributions are twofold. First, we contribute to a growing body of literature that examines women’s empowerment in developing countries [15,23]. In particular, we expand the limited understanding of how gendering influences business relationship development in the informal economy in developing countries. In doing so, we respond to multiple calls for further research on gendering in developing countries and in the agricultural context in particular [24]. Gender tends to be overlooked in poor economies despite women’s economic contribution [13]. Based on our findings and building on the literature on gendering, informal economy, and business relationships, we offer a theoretical framework and eight propositions. We observed at first that, in the agricultural sector in Uganda, men tend to be responsible for inter-organization business relationship development with non-family actors and mostly other men, while women support intra-organization relationships with family members. We learned that gendering impedes women from developing inter-organization relationships, which in turns limits their opportunities to be empowered and economically emancipated. Limited mobility, lack of trust by men, limited freedom to communicate as well as household duties and responsibilities for farming activities up until sales are the primary sources of impediments for female farmers in developing inter-organization business relationships. We observed that by forming small-scale cooperatives—which may include men but are mostly dominated by women—women can go beyond their family network. They can themselves establish inter-organization relationships with men and other female farmers and more easily access financial resources. Such cooperatives and collective actions empower women and make them economically more independent. They offer women greater opportunities to contribute to their family business as well as to their communities’ well-being [13]. Our findings corroborate those of Meier zu Selhausen (2016) and Pandolfelli, Meinzen-Dick, and Dohrn (2008), who contend that collective actions and social capital enable marginalized women to overcome gender biases in the informal economy in developing countries [2,25].

Second, in the context of developing countries that struggle to offer a better business climate, our study serves as a springboard for policy implications aimed at empowering women and at offering them a strategic economic role [1]. Given the key involvement of women in the agricultural sector and the importance of this sector to Uganda, men and women have much to gain from equality and empowerment of women in general. Our study reveals that gendering is not always done consciously and that a deep societal change is, thus, required to curb gendering. Agricultural cooperatives and community-level interventions that empower women to achieve lasting gender equity in the informal economy in developing countries are warranted [13,15]. Though said gender equality is not reached in Uganda, efforts to achieve this objective are not and should not be abandoned [15]. Empowering women and reducing gender inequalities are two key objectives of development policy [14,15,26]. In this line, development organizations have boosted the implementation of programs aimed at fostering women’s empowerment (for instance, in 2016, the UN Secretary General dedicated a panel to women’s economic empowerment).

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Gendering

Gender corresponds to the social or cultural categories by which relationships between the sexes are conceived [4,5,6]. Sex is given by nature, whereas gender is socially constructed. The process through which gender is constructed is performed individually, but with the physical presence of others. Gender results from legitimating oneself, in particular in social arrangements. Through gender, individuals comply with social norms that other expect within particular social arrangements. Socially constructed arrangements are often seen as “natural and rooted in biology” (West and Zimmerman, 1987, p. 128) [6]. However, they are a response to the differences created by gender, and they reinforce individuals’ behaviors that comply with the socially constructed arrangements [6].

According to West and Zimmerman (1987, p. 137), gendering refers to “creating differences between girls and boys and women and men, differences that are not natural, essential, or biological” [6,8,9]. An example of creating such differences is that women are expected to stay home and take care of the children, whereas men are expected to earn a living. As opposed to sex, gender does not exist prior to a particular situation but is created in the situation [7]. Gendering finds its roots in the phenomena of homosociality and homophily [5,20]. Those phenomena imply that people have a preference for the “same”. In the case of gender differences, this means that men have a preference for men and women for women. Gendering may also result from individuals’ cultural heritage [4,5,6]. For example, it might be culturally decided upon that men earn a living and women take care of the children, and this is not necessarily a result of homosociality or homophily. One could then argue that both homosociality and homophily originate from cultural heritages. It might be that someone has a preference for the same sex, in particular in social situations, as a result of one’s cultural background.

2.2. Business Relationship in the Informal Economy

Although there is no conclusive definition of an informal economy, Guma (2015, p. 307), citing Spring (2009), writes that “informal usually refers to unregistered, unregulated, and untaxed businesses, including service enterprises, production activities, and street vendor sales” [3,27]. Worldwide, the economy of nations consists of both a formal and an informal economy. According to Portes and Haller (2010, p. 404), in an informal economy, activities are “characterized by (1) low entry barriers in terms of skill, capital, and organization; (2) family ownership of enterprises; (3) small scale of operation; (4) labor-intensive production with outdated technology; (5) unregulated and competitive markets” [18]. Charmes (2012, p. 106) writes that can be defined by “referring to the characteristics of the economic units in which the persons work: legal status (individual unincorporated enterprises of the household sector); non-registration of the economic unit or of its employees; size under five permanent paid employees; and production for the market. … informal employment is defined by the absence of social protection (mainly health coverage) or the absence of written contract (but this criterion can only be applied to paid employees and is consequently narrower than social protection)” [28].

As in the formal economy, the ability to develop business relationships is critical in the informal economy. Business relationships are crucial for prospering within a competitive environment and for fostering productivity in value chains [16,17]. Business relationships are essential, as economic actors are embedded in networks in which resources are exchanged. It has been contended that business relationships originate from a combination of calculative and social concerns [29,30]. Some authors, however, argue that socialization more than rationality underlies the process of business relationship development [31]. These authors claim that business relationship development does not derive from rational decisions. Instead, they contend that socialization, an organizational behavior aimed at reducing the risk of opportunistic behaviors, fosters communication and knowledge exchange and leads to business relationship development. In general, being in a position to develop business relationships and to expand one’s social capital can lead to significant empowerment. Empowerment refers to a process by which those who have been denied the ability to make strategic life choices acquire such an ability [32]. Social capital generally denotes the features of social organizations, such as social institutions, associations or networks, and more informal networks of friends, relatives, and acquaintances.

Social capital is a key concept in development literature (for example, Grootaert and van Bastelaer, 2002; Woolcock and Narayan, 2000), and studies on the link between social and financial access in developing countries are burgeoning (for example, Aterido et al., 2013; Heikkila et al., 2016) [33,34,35,36]. Heikkila et al. (2016) find, for instance, that the positive effect of an individual’s social connections—understood as the quantity and quality of interpersonal relationships and trust (Glaeser et al., 2002)—on access to loans from financial institutions is more pronounced for poorer people, in rural areas, and in areas where generalized trust is low [35,37]. In other words, it appears that individual social capital is important precisely in those situations in which barriers to access are greatest. Despite the key role of the informal economy in poor countries, research on the income and wealth generated by the informal economy remains relatively scant [21]. There has, however, been a recent surge of interest in social networks and their role in the operation of the informal economy [38]. Through collective actions, activities such as training, the provision of credit and various community welfare services can take shape, thus guaranteeing more equitable distribution of resources to improve livelihoods for marginalized groups.

2.3. Business Relationships and Gendering in the Ugandan Informal Economy

For centuries, women’s economic position has been subordinate to men. In Western countries, women’s economic position has improved over time [10]. In developing countries, however, gender discrimination remains a major issue [13]. Despite the efforts of many gender activists, women’s economic position is still substantially subordinate to men’s economic position. In Uganda, the society is patriarchal, and men mostly make decisions [39]. The country’s civil wars and economic crises in the 1970s and 1980s had deep demographic and structural impacts [40]. Meanwhile, rogue regimes impeded women’s participation in business activities, often due, as Guma (2015, p. 306) states, to “persistent and systemic prejudice, discriminatory laws and policies, and financial constraints, as well as social-cultural, educational and legislative neglect” [3]. Although women play a significant role in Uganda’s economic development, they hold limited control over household assets and over the division of responsibilities in the household and their community. Most women are married or live-in male-headed households. Female workers in Uganda are usually unpaid family farm workers [1], and their level of empowerment directly depends on others in the household with whom they must negotiate when making decisions [39]. Even in rare situations where households are headed by female farmers, women do not benefit from equivalent resource endowments for pursuing their strategies as men in male-headed households. Like anywhere else, cultural, political, and economic institutions reinforce gendering and shape women’s and men’s access to and control of resources [25]. In many rural areas where small-scale agriculture takes place, gender differences have been found to have as significant impact on resource allocation as well as productivity in agriculture [41,42]. Barriers to women’s economic emancipation in Uganda are particularly substantial [3].

Given that women traditionally suffer from restricted access to formal education and capital in Uganda, informal sectors provide women with important avenues for income generation and accumulation of wealth [38]. In this informal context, we can also observe that the poorest women engage in collective actions to overcome obstacles to success, to develop their social network, and to generate income [25,38]. Pandolfelli et al. (2008) and Meier zu Selhausen (2016) show that collective actions remedy the marginalized position of women in sub-Saharan Africa and are a response to constraints within their households and wider social environment [2,25]. Participation in collective action through cooperatives is promoted as one promising strategy for women to overcome market imperfections and increase productivity and farm incomes [25,43,44,45,46,47]. Based on the perspective that business relationships are a result of both a socialization process and the rational imperatives of economic actors, we assume that the development of those relationships should be affected by gendering. In the Western formal economy, it is presumed that gendering has a moderate impact on business relationships in general, women’s economic position having increased substantially. In Uganda, however, a large body of literature acknowledges that gender differences are embedded within the culture [1]. We, therefore, aim to further the understanding of the role of gendering in the development of business relationships in the agricultural sector in Uganda. This endeavor addresses calls for more research on gendering and its impact in this particular context (i.e., the informal economy in developing countries) [24].

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context

Data collection for this study took place in 2017 in collaboration with the AGRI-Quest research project. This project aimed to establish a better business climate in the agricultural sector of Uganda by strengthening ethics and quality standards among local small-scale economic actors. The main objectives of the research project undertaken between 2016 and 2019 were to help value chain players design quality mechanisms and codes of conducts, to train them in local and international agricultural policies and standards, to support farmers in selling and buying ethically, to provide them with skill in documenting and reporting, and to facilitate dialogue among farmers.

During the data collection period, our local partner focused on four different value chains, which were rice, cassava, potato, and dairy. In our study, we concentrated our attention on the rice and cassava value chains, and we identified the regions in Uganda that were particularly useful for studying these value chains. The data collection was performed together with the local team of the applied research project. We used a variety of data to analyze the agricultural situation with regards to business relationship development.

3.2. Research Design

Qualitative research was determined to be the most appropriate research design, firstly because the main research question requires a qualitative design. That is, the research should answer a “how” question, which in general requires a qualitative research design [22]. To clarify, “how” questions are often questions aimed at explaining how a certain event evolves over time. The understanding of such a process requires a narrative in which the order and sequence of events are captured [48]. Our research reflects an inductive approach to theorizing the dynamics of doing gender in Uganda. An inductive research design was chosen for two reasons. First, the current state of literature on the relation between gendering and business relationship development in informal economies can be described as nascent [49]. Second, at the core gendering constitutes a process. Qualitative research suits best when the aim is to explore such a process, as it allows the researcher to understand the context in which actions and decisions are embedded. Furthermore, a qualitative research design emphasizes the generation of new theory that could explain the process and is characterized by an iterative and inductive approach [49].

We closely followed the methodology described by Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (2013) [50]. This methodology allowed rich contextualization, vivid description, and an appreciation of subjective views, as we aimed to capture and interpret the point of view of the “natives” [51]. The qualitative data entailed seven interviews, three focus groups, 13 group conversations, and one factory visit, all supported by observational/field notes and photographs. Table 1 presents a summary of the data sources. Our empirical work was, therefore, based on multiple sources of data that allowed for triangulation.

Table 1.

Summary of the data sources.

One co-author of this study traveled through the country, where it is a cultural habit not to make appointments in advance. It was, thus, essential to remain open to and anticipate emerging situations. Due to cultural heritage in Uganda, administering surveys was not the most efficient way to collect data. Ugandan people are more willing to take time to answer questions in the form of interviews. Since the aim of the research was to gain a deeper understanding of attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and processes, interviews were an appropriate technique [52]. The interview questions were developed in such a way as to capture the difficulties that economic actors encounter during their work and to find out whether these difficulties are caused by gendering. More specifically, the aim of the questions was to find out if these difficulties influence business relationship development. Our interview guides can be found in Appendix A.

In addition to interviews, observational notes and photographs were taken to enhance our understanding of underlying processes. Both observational notes and photographs supplemented the recorded interviews and enabled a comprehensive and integral understanding of the answers provided by the interviewees. For example, during the majority of the interviews, the women were sitting on the ground, whereas the men were sitting on chairs (Scheme 1). Some answers to certain questions gave the impression that gendering had no influence on the issues discussed. However, as implied by the interview setting in which women had to sit on the ground and men could sit on chairs, gendering had a large impact. Interviewees were not always aware of this impact. The supporting observational notes and photographs enabled us to grasp this particular act of gendering. Our aim while making observational notes was to write down everything that seemed relevant concerning gendering. Therefore, we explicitly made a distinction between women’s and men’s behavior during the observation.

Scheme 1.

Farmers in Bugiri District—Typical interview setting. Source: own field research.

(Scheme 1 presents farmers in Bugiri District—Typical Interview Setting).

3.3. Data Collection

Bugiri—Rice District. The first face-to-face, focus group and group interviews were conducted in the district of Bugiri, which is known for its rice production. The interviews were held with governmental entities, farmers and farmer groups, input dealers, buyers, and millers. Interviews were conducted in English and in different Ugandan languages. We were assisted by a local support staff member, who was the district guide working for a local non-governmental organization (NGO). The district guide arranged the interviews and was responsible for translating most of the interviews from the local language to English and vice versa during the interviews. We conducted the interviews together with the local project team and the district guide in the sub-counties of Bugiri town, Buwunga, Kapyanga, Bulesa, Nabukalu, and Nankoma. Interviews were also documented through photographs of the interview sites. We recorded the interviews and wrote down detailed field and observational notes.

Oyam—Cassava District. The subsequent seven interviews and one factory visit were conducted in the district of Oyam, known for its cassava production. Interviews were held with a governmental entity, an input dealer, and one farmer group and were conducted in English and in different Ugandan languages. The district guide arranged most of the interviews and was responsible for translating most of the interviews from the local language to English and vice versa during the interviews. However, during one of the interviews, the respondent referred to a farmer who was very influential in the district. The contact details of this particular farmer were provided, and an additional interview was arranged with this farmer. We recorded the interviews, wrote down field and observational notes, and took supporting photographs of these observations and interviews.

Kampala—Capital City. The final interview was conducted in the capital city of Kampala. The interviewee was a successful female director of an organization dealing with medical waste. The interview was conducted in English. We recorded this interview and took notes.

3.4. Data Analysis

The qualitative data analysis was performed iteratively and encompassed three stages: transcribing of interviews, coding of interviews, and coding of observational and field notes. We drew on inductive coding methodologies [50,53] to develop theoretical categories and to identify themes as they emerged during data collection. This process was guided by an interpretive and context-sensitive approach to understand the concept of doing gender from the perspective of those involved. This methodological framework allowed us to offer an enriched understanding of human sociocultural experiences and how meaning is communicated, generated, and transformed by the participants of our research [54].

The interviews were coded using Atlas.ti. We started the data analysis by reading and re-reading the interview transcripts and field notes and by grouping individual descriptions of the different perceptions of our informants via open coding [51] into basic categories that represented “a slightly higher level of abstraction-higher than the data itself” [55]. This type of analysis ensures that the richness of the data is preserved. In the first phase of coding, we read all the interviews and labelled relevant parts. Afterwards, the analysis continued with the development of first-order concepts from the selected parts of the data, in which the content remained close to the original data. These emerging first-order concepts are based on the different descriptions detected previously, giving “those categories labels or phrasal descriptors (preferably retaining informant terms)” (Gioia et al., 2013, page 20) [50]. We then gradually added further data such as interview quotes and field notes for the purpose of developing more robust theoretical concepts, and we iterated between the data and emerging categories [53]. Whenever we found an interesting theoretical category in a particular type of our data (e.g., interview quotes), we compared this with other data from our repertoire, such as field notes, and revised our analysis. Because we stayed close to the original data, the interrater reliability—which means that other researchers are likely to perceive and label the data similarly [50]—was higher.

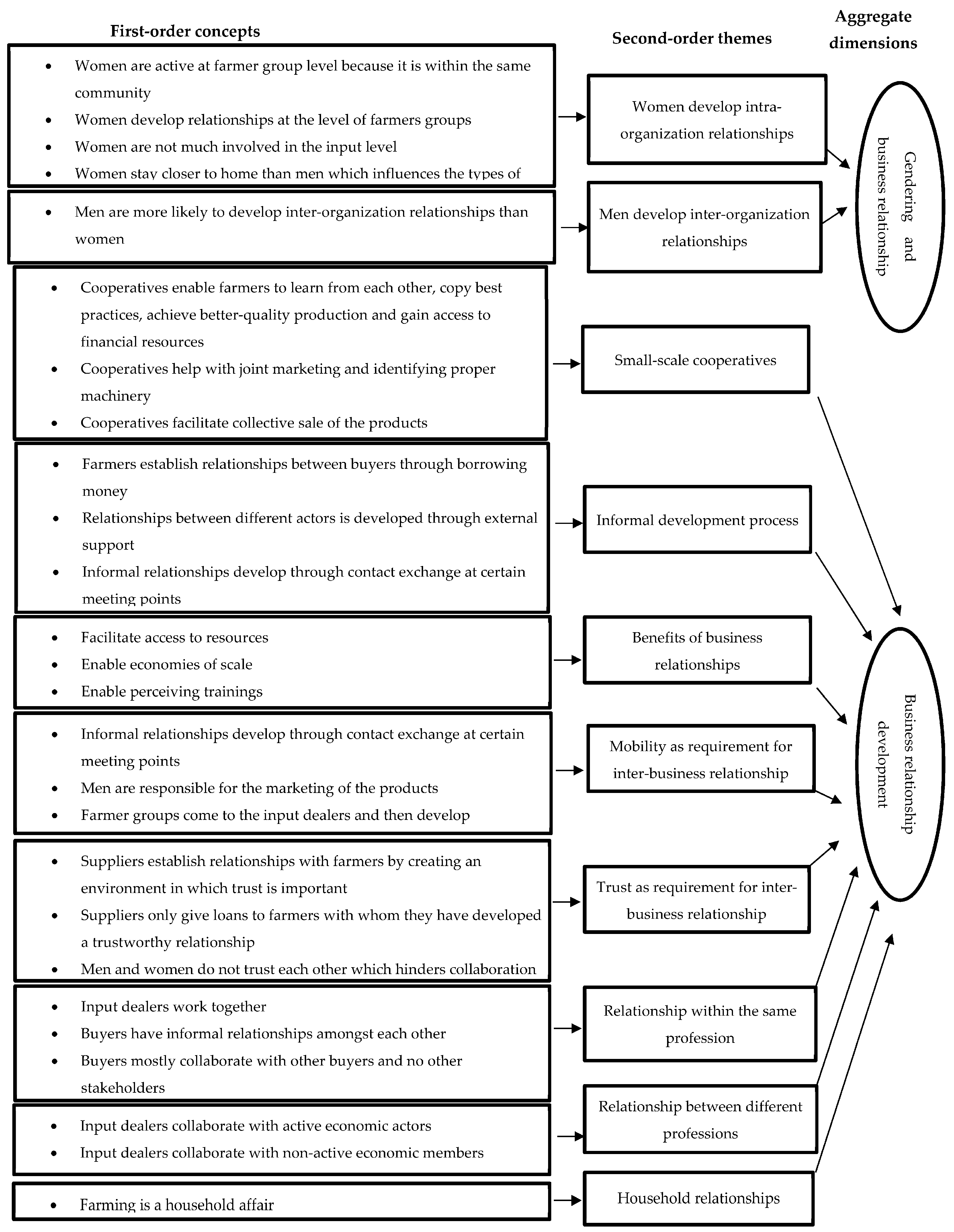

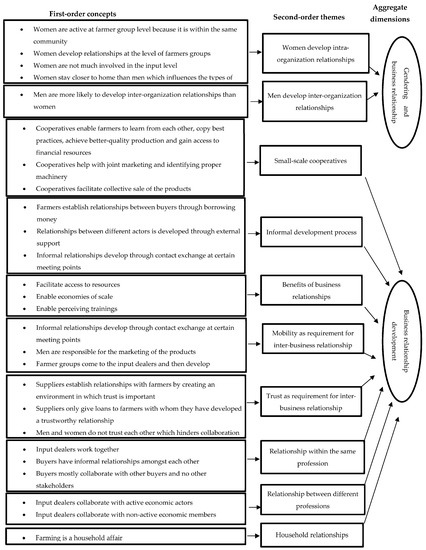

The analysis resulted in different concepts that were further developed into second-order themes in which a shift from informant-centric terms to researcher-centric and theory-based terms occurred. Finally, these concepts were combined into aggregated dimensions, which are the most abstract concepts. The first-order concepts, the second-order themes, and the aggregated dimensions are the basis for the data structure (Figure 1). We compared interview statements by different informants and triangulated our multiple data sources (i.e., interviews, pictures, field notes, and field observations).

Figure 1.

Data structure.

4. Findings

In this section, we present a detailed description of the themes that emerged while we analyzed the data.

4.1. Theme 1: Business Relationship Development in the Agricultural Sector in Uganda

4.1.1. Inter-Organization Business Relationships and Intra-Organization Business Relationships

The data show that business relationships take two main forms: inter- and intra-organization relationships. It appears that the two are significantly interrelated, and we elaborate on both types to offer a coherent picture.

Inter-organization relationships. Inter-organization business relationship development refers in our study to the process of developing relationships between actors, either individuals or united actors acting as one economic actor, representing different organizations for business purposes. These relationships can involve actors with either the same profession (i.e., same stage of the farming value chain) or different professions (i.e., different stages of the farming value chain). The active economic actors in our study were farmers, input dealers, traders, and millers. Active economic actors refer to those actors who perform activities along the farming value chain. As an illustration of relationships taking place between actors of the same profession, we refer to a quote from an input dealer from Idhatujje Agencies Ltd. (Kampala, Uganda), who said, “we collaborate with all registered agri input companies.” Relationships between actors of different professions could be between farmers and input dealers. It is important to note that these relationships can go beyond the active economic actors. Actors such as governmental entities and NGOs support value chain activities and develop relationships as well.

Cooperatives are one form of inter-organization business relationships. They are created, with or without support from governmental entities and NGOs, to support farmers. Interviews revealed that when farmers belong to cooperatives, they can learn from each other, copy best practices, achieve better-quality production, and gain access to financial resources. One interviewee explained: “we learn how to plant and learn about post-harvest handling and equipment training.” Another interviewee added: “working together helps with joint marketing and identifying proper machinery.” Depending on the cooperatives, different stages of the farming value chain can be represented such as farming, catering, and loan association. Cooperatives may also facilitate the collective sale of the products. In this regard, one interviewee from a farmers’ group in Bugiri explained that selling collectively enables farmers to sell their products more easily.

Intra-organization relationships. Intra-organization relationships are relationships between actors within the same organization. In the context of this study, the majority of the intra-organization relationships entailed household relationships, which are mainly relationships between relatives. Intra-organization relationships can also be among actors who do not belong to the same family. However, the data made plain that the majority of the businesses are family owned; thus, the majority of the intra-organization relationships are between relatives.

“Now farming, being a household affair, it means that everybody [every family member] is involved at some stage or another.”(Catherine Tindiwensi)

Other interviewees confirmed this finding, such as the cousin of an input dealer, Kica Sharon. She is a farmer and said that she collaborates with her uncle. She was working in her uncle’s shop when the interview took place (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Kica Sharon in her uncle’s shop. Source: own field research.

(Scheme 2 presents Kica Sharon in her uncle’s shop.)

4.1.2. Informal Business Relationship Development

The findings indicate that the process of developing business relationships is largely informal. Data collected did not reveal any structured or formalized manners of establishing relationships. Instead, most interviewees claimed to establish relationships in unstructured ways. For example, relationships develop simply through exchanging contact details in the case when someone has a certain crop.

“So how the relations develop, they are informal, but what happens is that the Kampala traders first come, and when they come, they first exchange contacts, so once the season comes, either these ones call them and say I have buns of rice or the other way around. You have rice, then the relationship can go from there.”(Translated by Catherine Tindiwensi)

4.1.3. Requirements for Inter-Organization Business Relationship Development

The data revealed two main requirements for inter-organization relationship development.

Mobility. Relationships between different organizations require that actors physically meet. In Uganda, inter-organization relationships are established in physical situations, and not through any virtual meeting points. Thus, for different actors to meet, a physical meeting point is necessary. Mobility is, therefore, a requirement to establish relationships. At least one actor must be able to physically go to a certain point where other actors are present.

Trust. Trust is the second requirement that emerged as essential to inter-organization relationship development. Suppliers, for example, establish relationships with farmers by creating an environment in which trust is important. Kalulee Ivan described this process as follows:

“What we do is, first we create an environment between us and the customer. So we make sure that the product we have at least is genuine. So when the customer knows your product is genuine or it works, he does what? He comes back and tells others and brings them towards you. So this is how you create a relationship.”

Likewise, it appears that farmers prefer to sell their products to people they trust. As the agricultural officer in Oyam stated:

“One thing is that a seller has liberty, has freedom to choose who he wants to sell to. And therefore, he sells to the person he trusts most. He sells to the person who he thinks will give him better money. He sells to somebody who he thinks is transparent. So overall there is transparency between a seller and a buyer.”

The data show that the requirements are especially relevant for inter-organization relationship development, because family-related relationships do not necessarily require mobility given that family members often live together. In addition, men and women often do not trust each other. This lack of trust prevents relationship development between men and women who are non-family members. This quote from Catherine Tindiwensi illustrates the inability of women to work with male non-relatives:

“When women go out of the network they are likely to interact with more men than women, and that could also bring suspicion amongst the spouses.”(Catherine Tindiwensi)

4.1.4. Economic Benefits of Inter-Organization Business Relationship

The economic benefits mentioned in the interviews are summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Benefits of business relationships.

(Table 2 presents the economic benefits of business relationships).

4.2. Theme 2: Gendering in the Agricultural Sector in Uganda and Effects of Gendering on Inter-Organization and Intra-Organization Relationship Development

4.2.1. Gender Separation

Our data revealed that there are cultural and societal expectations about the role that women and men are “supposed” to have within the society. For example, Catherine Tindiwensi described the expectations regarding mobility as follows:

“But also like I mentioned the social, cultural values and expectations of women regarding mobility. Generally a good wife should be like home-based, not too mobile, not too aggressive, those are just societal expectations, but which reflect and impact on how women transact their businesses and network.”

The cultural expectation is that women are supposed to stay at home and men are supposed to travel leads to gender separation. Scheme 3 and Scheme 4 illustrate the gendering that takes place in the Ugandan agricultural sector.

Scheme 3.

Typical interview setting where women are subordinate to men by sitting on the ground. Source: own field research.

Scheme 4.

Woman working on land while taking care of child. Source: own field research.

4.2.2. Inter-Organization Relationship Development Is Mostly Undertaken by Men

Since women do most of the work other than sales, relevant intra-organization relationships—that is, relationships that for the greater part contribute to the performance of an organization—are between women. Men generally contribute at the end of the production phase by taking the products to the market but do not contribute to activities before that stage.

“But at the end of the day, they [the women] end up being the biggest contributors to farming. Females are by far the biggest contributors to farming. Most of the farming you are seeing is being carried out by women, more than 60% of the work I think. And the male will only be about 40%.”(Nelson, district leader)

Men’s contribution often begins at the moment of selling the products. At this particular moment, other actors apart from relatives come into play. Men are then able to develop inter-organization relationships, since they meet actors outside the family. Field expert Catherine Tindiwensi confirmed this finding:

“So if you look at farmer organizations as a farm, then they [the women] have like intra-firm relations, intra, within their group. They are stronger at intra-farm relations, or intra-firm relations. Women tend to be closer to home […].”

This statement explains that women stay close to home and do not develop inter-organization relationships. Instead, they develop intra-organization relationships. Besides farmers, the data show that women are not likely to develop inter-organization relationships in other parts of the value chain. In these other areas, women also perform many activities but are not allowed to be in contact with other men. Men tend to believe that women will cheat. They prevent their wives from working with other men. In addition, in these areas, the majority of the actors are men, because many of these professions are perceived to be male professions. Due to a lack of female participants, men mostly develop inter-organization relationships. An input dealer from Idhatujje Agencies Ltd. mentioned “we collaborate with all registered agri input companies.” This comment raised the question of whether he worked mostly with men or women. He answered, “with all sexes, men and women.” Therefore, we asked if women experience any difficulties working in this area. The input dealer replied, “women are not much involved, because at times they are marginalized by their husbands.” While he implied that input dealers could work with women, however this rarely occurs, since women are not significantly involved at this stage. He confirmed this by saying “at the input level, few of them, we interact with a few of them [women], because mostly it is the men that come here to buy chemicals.” Thus, inter-organization relationship development mostly takes place between men.

4.2.3. Intra-Organization Relationship Development Is Mostly Undertaken by Women

In the case that both women and men are present within an organization, intra-organization relations are inevitably between women and men, and not solely between women. The data indicate that women mostly collaborate with each other within an organization, because (1) women do most of the work up until sales and (2) women are not likely to develop inter-organization relations. Women do most of the work. This impedes women from developing relationships with actors apart from those with whom the women directly work. That is, women directly work with their relatives and thereby develop intra-organization relationships. Moreover, women are expected to perform additional activities, such as taking care of the children and searching for firewood and, thus, have few opportunities to develop inter-organization relationships.

4.2.4. Small-Scale Cooperatives by Female Farmers

The effects of gender inequality on the agricultural sector in Uganda are substantial. However, those effects seem to be mitigated in certain situations. Based on our data, we see that mitigated influence of gender inequality occurs when women (1) are empowered and (2) have access to incomes. For example, gender inequality makes men more powerful than women. Men have the decision-making power, and women are subordinate to men. However, in situations where women had more economical power, the women appeared to be less subordinate to the men. In fact, women had the final say in such situations. Women increased their power by working in groups of female farmers and thus obtained various economic advantages. For example, one farmers’ group, Adyegi Women Health Network, started a group because:

“[…] they’ve [the women] been facing challenge of education or money, income. So they started this group in order to facilitate them in saving and borrowing money.”

This particular group, dominated by women, offered economic power to women and thereby reduced the effect of gender inequality. Women appeared to have the decision-making power.

“Women sit on the ground. They shake hands while being on their knees. However, men also sit on the ground”(Adyegi Women Health Network, observational note, 12 April 2017).

Increased income is another factor that appears to reduce the effects of gender inequality. Margret Mwanamanze described such a situation:

“So imagine, with that kind of approach, and if people can access money, people have better chances, people have jobs, people have high income, the calamity of criminal cases and all that would be reduced as well as gender violence, because we are known for that as well, the gender violence in the homes: men battering women and women battering men. So, I imagine if each one of them has income, because we encourage both women groups and men, once the woman has an income the man will relax a bit, because they don’t always have to ask for money from their husband.”

Thus, the women can spend their own money instead of being dependent on the men. According to Margret Mwanamanze, men respect women if women have their own income. Therefore, the government even promotes an income for women (Margret Mwanamanze, field notes, 5 April 2017). In addition, a female farmer from the farmers’ groups Umoja, Agali Awamu, and Bukyere said “For the women, we are now comfortable, because we are always comfortable when our husbands are comfortable, because there is an income now.” Both of these situations imply that the effects of gender inequality are at least slightly reduced with increased income. In the latter example, it is implied that the increased income causes the husbands to let their wives be. In other words, the wives are not forced to perform activities but have the liberty to decide on their own.

“Remarkable situation: only a woman was able to speak in English and translated almost the entire interview from the locale language to English, and the question about gender was answered first by a loud applause from the interviewees.”(Loro Note En Teko Co-Operative, observational notes, 12 April 2017)

Eventually, by forming or joining small-scale cooperatives, women are empowered and get access to sales related activities. Scheme 5 illustrates women’s empowerment. As explained by Moses, the manager of Sasakawa Africa Association:

Scheme 5.

Increased power for women: women sitting on chairs, Loro Note En Teko Co-Operative. Source: own field research.

“Women take the lead in improving the quality. They are the ones who clean. So, they are fully involved in practical post-harvest handling and trainings. And we are also promoting them even to market on the marketing committee, electing them on those marketing committees. We give them power. […]Today we are promoting that, empowering them, both from production to marketing.”

(Scheme 5 presents Increased power for women: Women sitting on chairs, Loro Note En Teko Co-Operative.)

5. Theory Development: How Does Gendering Influence Business Relationship Development by Female Farmers in Uganda?

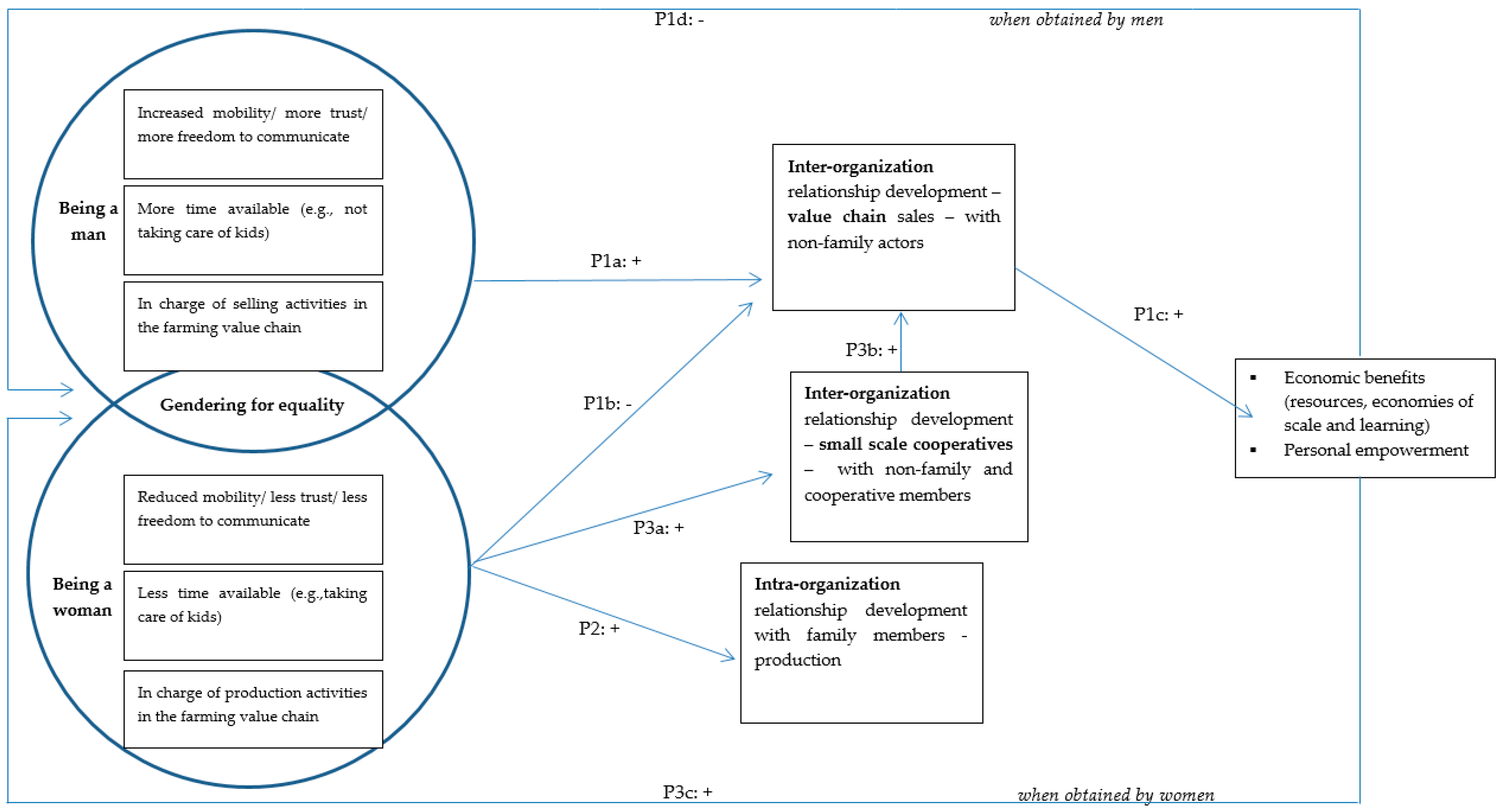

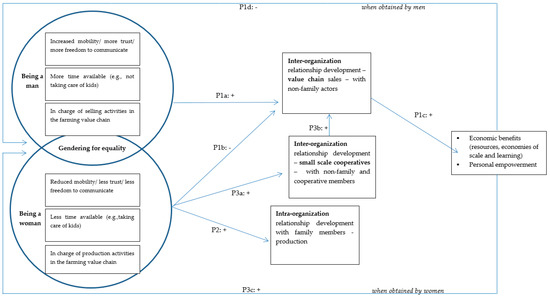

Our framework consists of eight propositions and reveals how gendering influences business relationship development in Uganda and how forming small-scale cooperatives empowers female farmers (Figure 2). The proposed conceptual model builds on the literature on gendering, informal economy, and business relationship development. In particular, it uncovers relationships between gendering, the types and characteristics of business relationship development, and the level of empowerment of women and men in agricultural Uganda. In the following section, we explain these linkages theoretically and build corresponding propositions that serve as starting points for further empirical inquiry. Such understanding is essential to move the discussion forward in seeking greater gender equality and to initiate the right steps and appropriate efforts towards a better and more prosperous business climate in the agricultural sector in Uganda.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework.

(Figure 2 corresponds to our theoretical framework).

5.1. Gendering, Informal Economy, and Inter-Organization Business Relationship Development in Uganda

Our findings suggest that, in our particular setting, individuals perform gendering intentionally and reflexively as well as unintentionally and non-reflexively. Women kneeling in front of men while introducing themselves or sitting on the ground are evident demonstrations of gendering. These acts also seemed to be natural social arrangements to the men, indicating that men and women were not reflexive about this behavior [8,9,20]. In their interactions with others, women and men also perform gender intentionally. For example, during certain interviews, female interviewees made clear by their answers that they were not allowed to talk about the subject of gender. This illustrated that women were aware of their unequal position compared to men and deliberately decided to comply with this social arrangement.

Furthermore, data suggest that accounting for the context is critical to understand the triggers of business relationship development. In informal economies in particular, inter-organization business relationships are rarely prescribed by contractual arrangements and are instead randomly established without any recurrence. Establishing inter-organization business relationships along the value chain (i.e., among farmers, input dealers, traders, governmental entities, and millers) is essential for achieving economic benefits and business purposes. Such relationships enable economic actors to access resources, reach economies of scale, and learn. We observed that, in agricultural Uganda, the majority of inter-organization relationships are established by men, between men, and between non-family members. Our findings illustrate that gendering prevents women from developing inter-organization business relationships with non-family actors in three main ways. First, Ugandan citizens, especially in rural areas, expect women not to travel for business purposes. However, mobility, as the data revealed, is required to develop inter-organization relationships. Second, gendering causes men not to trust women and vice versa. Trust is a key requirement to develop inter-organization relationships. Third, women are not always allowed to communicate with the opposite sex apart from their relatives, which is clearly a constraint for women to develop inter-organization relationships. Cultural heritage in Uganda implies that, although women contribute more to the farming process up to sales, men are in charge of the sales of products on the market and are, thus, in a position to develop inter-organization business relationships with non-family actors. This ability empowers the men, brings them economic benefits, and places them in the role of decision makers.

Our findings complement those of Guma (2015) [3], who contends that inability to save [56] and make social connections, which are a source of credit and market information [57] substantially impedes women’s economic independence in Uganda. Furthermore, women’s limited ability to inherit lands or businesses and their insecure rights to own or occupy land affect their possibilities to invest and contribute to Uganda’s economic growth [58].

Furthermore, our findings support those of Jones et al. (2012) and Meier zu Selhausen (2016), who contend that, in Uganda, women are vulnerable to exploitative trading practices and have weak bargaining positions with predominantly male networks in the value chain [2,59]. This status limits women’s agricultural productivity [24,60] and constrains their ability to move from subsistence agriculture to more profitable higher value chains (World Bank and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2009). Therefore, we propose:

Proposition 1a.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, inter-organization business relationships are mostly developed by men with non-family actors and between men in order to bring products to the market. Men can develop these inter-organization relationships due to (1) their mobility, trust by other men, and freedom in communication and (2) their focus on value chain activities related to sales.

Proposition 1b.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, inter-organization relationships are rarely developed by women. Women can rarely develop these inter-organization relationships due to (1) their restricted mobility, lack of trust, and limited freedom in communication and (2) their focus on value chain activities up until sales.

Proposition 1c.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, inter-organization relationships enable men and women to attain (1) economic benefits, including privileged access to financial resources, and (2) personal empowerment.

Proposition 1d.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, men’s greater ability to attain economic benefits and personal empowerment through inter-organizational business relationships fosters gendering acting in favor of gender inequality and the marginalization of women in the long run.

5.2. Gendering, Informal Economies, and Intra-Organization Business Relationship Development in Uganda

We observed that, in agricultural Uganda, women essentially establish intra-organization relationships with relatives. The fact that women’s time is constricted by a greater household labor load than men’s and that female farmers devote their time to farming activities up until sales—in other words, they focus on food security over market gains [13]—considerably reduces opportunities to expand interactions beyond their family network. Building and maintaining social capital is costly in terms of time and other resources [61]. Women typically have a high opportunity cost of time that reduces their ability and incentives to develop their social capital and network. They join groups that mobilize fewer resources than men because they are resource-constrained [62]. As written by Katungi et al. (2008, p. 37), “Women are often more dependent on informal networks based on everyday forms of collaboration, such as collecting water, fetching fuel wood and rearing children. These services, together with the fact that women have a high opportunity cost of time, may motivate women to form networks with individuals who are geographically close to reduce the length of time required for travel for social interaction. However, geographically close networks tend to be limited in their scope of information transmission (Granovetter, 1973)” [41,63].

Our findings, thus, question the assumption that business relationships are built from a combination of socialization processes and rational imperatives [29,30]. While in Western society, for any economic actor, business relationships can result from both socialization and rational triggers, these findings illustrate that in informal economies, business relationships tend to develop from socialization rather than from a rational perspective. Gendering tends to reduce the role of rationality in building relationship and instead magnifies the importance of socialization. Therefore, our findings suggest that gendering plays a critical role in doing business in informal economies. Gendering influences in particular the extent to which both socialization and rational processes underlie business relationship development in informal economies. Where gendering has a substantial impact on such relationship development, socialization rather than rationalization processes prevail. In Uganda, gendering is rooted in the cultural heritage and also in the phenomena of homosociality and homophily. In line with Meier zu Selhausen (2016), our findings support the view that culturally embedded patriarchal conditions in Uganda restrict women’s ability to control resources and to make autonomous choices. These conditions create barriers to their exploitation of economic opportunities and personal capabilities [2,64]. Therefore, we propose:

Proposition 2.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, intra-organization business relationships are mostly developed by women with family members in order to undertake value chain activities up until sales. Women develop these intra-organization relationships because focusing on this development enables them to combine (1) their household duties (e.g., taking care of the kids) and (2) their focus on farming activities up until sales.

5.3. Small-Scale Cooperatives as a Means to Achieve Empowerment and Economic Benefits

Small-scale cooperatives enable female farmers to reduce the gender inequalities caused by gendering in Uganda. These small-scale cooperatives—mostly dominated by women—offer opportunities for women to develop inter-organization business relationships with other women and men outside their family network. Through grouping, female farmers improve their ability to establish business relationships, which in turn enable them to access certain external resources and achieve greater empowerment and economic independence. When women have more economical power in general, they are less subordinate to men and more likely to have the final say. Kabeer (1999) highlights that participation in collective actions clearly represents a life choice and, hence, an opportunity for women to be empowered [32]. Furthermore, community and cooperative structures suit women, who tend to emphasize intuition and consensus, rather than hierarchy [26]. Criado-Gomis et al. (2020, p. 5) points out, women’s motivation is “often directed towards achievement, valuing social and qualitative aspects over pure economic ones, working with local networks, and pursuing a balance between non-economic and economic objectives” [65]. In this same vein, we learn from the study of Chiputwa and Qaim (2016) that when female coffee farmers in Uganda have a greater control of coffee production but also monetary revenues from sales, a positive impact on nutrition is observed [66].

Our findings also suggest that, although gendering is relevant in every social situation and rarely disappears [7], it can evolve and corresponds to “an ongoing activity embedded in everyday interactions” [6]. Social arrangements are a response to the differences created by gender; they reinforce individual behaviors that comply with these socially constructed arrangements, or as shown in our study, they can be circumvented and impact the contextual gendering itself in the long run. Women can then become autonomous agents of change [13]. As Pandolfelli et al. (2008, p. 4) states, “gender roles, which vary among cultures and are crosscut by a multitude of identities, such as ethnicity, religion and class, are dynamic and change in response to the shifting economic, political and cultural forces in which they are embedded” [25]. Therefore, we propose:

Proposition 3a.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, female farmers form small-scale cooperatives with non-family actors, who are mostly other women.

Proposition 3b.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, small-scale cooperatives enable women to develop inter-organization relationships notably to bring products to the market.

Proposition 3c.

In the agricultural sector in Uganda, the ability of women to attain economic benefits and personal empowerment through small-scale cooperatives fosters gendering acting in favor of gender equality and reduced marginalization of women in the long run.

6. Discussions and Policy Implications

This study contributes to the discussion on the influence of gendering in the informal economy in developing countries and on women’s empowerment through collective actions in this context [15,23]. In sub-Saharan Africa, a large share of the population depends for its livelihood on informal economy (e.g., subsistence farming and small unincorporated enterprises) [21]. Women are particularly engaged in the informal business activities, as they face many barriers to formal economy participation, access to capital being mostly limited to men in sub-Saharan African countries [67].

We found in particular that gendering goes beyond the fact that Ugandan female farmers perform the majority of the household activities (such as taking care of the children) or that they have less time to devote to business expansion and their own empowerment and economic position [1,68]. In the informal agricultural economy in Uganda, gendering deeply influences women’s ability to develop inter-organization business relationships and thereby to become economically dependent and empowered. Women indeed have restricted mobility, are not trusted by men, and are limited in their freedom to communicate with men; all these impediments keep women from expanding the business of their organizations. In the agricultural sector in Uganda, gendering leads women to develop intra-organization business relationships with family members, and while men develop inter-organization business relationships with other men and non-family actors. Gendering can be simultaneously unintentional and reflexive. It is deeply rooted in the cultural heritages as well as in the phenomena of homosociality and homophily. Compared to Western countries, where business relationship development results from both rational imperatives and socialization, we see that gendering makes it such that triggers for relationship development are of a socialization rather than a rational nature in Uganda. Interestingly, we observed that female farmers form small-scale cooperatives to overcome gender inequality; such grouping gives them the opportunity to form inter-organization relationships with non-family actors and to more easily gain access to financial resources. Such cooperatives enable female farmers to empower themselves and, in the long run, can influence gendering itself in Uganda. Gendering is indeed contextual [7,8]; behavioral practices and social arrangements are consequences but also antecedents of local gendering activities. Our findings further the understanding of gendering, which is highly contextual, and which remains relatively absent from the literature on collective actions and social capital, particularly in the context of informal economies [25,41].

We can draw policy implications from our results, as they offer insights into how to mitigate and overcome the harms of gendering on the economic development of developing countries. Although efforts have been made throughout the world to reduce gender inequality, differences are far from erased. Gender is not always done consciously and requires a deep societal change. We encourage, in particular, facilitating the grouping of women in cooperatives, as cooperatives and collective actions enable them to empower themselves, overcome economic barriers, and actively contribute to their family and organization’s well-being. Many types of interventions can be implemented to increase women’s economic empowerment such as skills training and business or financial training, training in a trade or profession, as well as microcredit, larger loans, and grants [15,23]. Besides grouping, trust in women and their mobility should both be enhanced, as those two dimensions are prerequisites to their economic emancipation. As the degree of women’s empowerment may directly depend on others in the household, it is critical that others—namely their husbands—are receptive to efforts to increase their empowerment [15,69]. In this line, Ambler et al. (2021) stress the importance of couples-targeted interventions to improve gender equality [15].

In a longer-term perspective, Uganda could highly benefit from turning female farmers into decision makers, as women demonstrate greater social and environmental commitments than men. According to Glazebrook and Opoku (2020:11), “women bring transformational change by displacing the goals of capital with their labor practices of caring for family and community through collective, practical effort” [13]. The study of Chiptuwa and Qaim (2016) shows as well that empowering women in coffee agriculture in Uganda through control of coffee production and monetary revenues from sales fosters gender equality, which in turn, has positive impact on nutrition and dietary quality in smallholder farmers in Uganda (i.e., calorie and micronutrient consumption) [66]. Gender equality contributes to poverty reduction and rural development in developing countries. Furthermore, although it has often been argued that female farmers’ lower levels of physical and human capital result in lower measured productivity or inability to respond to economic incentives, a review of studies undertaken in the late 1980s and early 1990s found that when differences in inputs are controlled for, we do not observe significant differences in technical efficiency of male and female farmers [70]. In this same vein, a study by Osunsan (2008) reveals that businesses owned by Ugandan women perform quite well, although not as well as those of their male counterparts due to educational, managerial, and financial support differentials [39].

7. Limitations, Avenues for Future Research, and Conclusions

Despite the previously described contributions, our study has several limitations that could form the basis of future research. First, in qualitative research, some degree of subjectivity is always inherent. Although this qualitative endeavor was performed with high rigor, subjectivity cannot be avoided entirely. Second, during the fieldwork, it became apparent that gender is a sensitive subject, which has likely biased some of the answers provided by the respondents in at least two ways. Firstly, some people avoided answering the proposed questions, and secondly, others provided answers that were most likely not based on the truth. The latter situation seemed to occur often in the presence of both men and women, where the women were not able to speak freely. By analyzing both interview transcripts and observational notes and photographs, we could mitigate those biases. Third, while this study offers rich insights into the effects of gendering on relationship development within the agricultural sector in Uganda, it remains important to investigate whether our findings are transposable to other similar settings (i.e., country and region). Gender norms are dynamic and not easily generalizable [25]. Finally, research can further investigate possible impediments to women’s participation in collective actions and cooperatives, as the long-term survival and growth of these cooperatives depend on their members’ motivations, their active participation, and the economies of scale they can together achieve [2,71,72]. Pandolfelli et al. (2008) noted that the poorest women may still face important constraints in their attempts to participate in collective actions [25]. As the authors point out, if not carefully implemented, collective actions may eventually benefit the already well-off while perpetuating the impoverishment of marginalized groups. Further research needs to focus on how gender shapes women’s and men’s incentives and abilities to engage in, and benefit from, collective action [25].

Author Contributions

Original draft preparation, A.T.; Supervision, C.W.; Review and editing: V.D. and B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Interview guides for women within explicit organizations |

| Introduction |

| 1. Could you introduce yourself? |

| 2. What is your profession? |

| Relationships |

| 3. What is your position within the business? |

| 4. Could you elaborate on with which actors you collaborate/have to deal with? |

| a. With whom do you have to work within the organization? |

| b. With whom do you have to work outside of the organization? |

| c. Why do you need to work with these particular actors? |

| d. Which actors depend on your work? |

| 5. How do you perceive your relationships with others? |

| 6. Could you describe how you develop relationships with other actors? |

| 7. Do you experience any difficulties while developing these relationships? |

| a. If yes, could you describe these difficulties? |

| b. What do you see as the cause of these difficulties? |

| c. And why do you believe that this is the cause? |

| 8. Are there any facilitating factors for developing relationships? |

| a. If yes, could you describe these factors? |

| b. What do you see as the cause of these factors? |

| c. Why do you believe that this is the cause? |

| 9. Could you describe what the goal is of the relationships you develop? |

| Gender |

| 10. What makes your life difficult? |

| 11. To what extent is that based on you being a woman? |

| 12. Could you describe how being a woman affects your work? |

| 13. Could you describe how being a woman affects building relationships within the |

| value chain? |

| Closing of the interview |

| 14. Thank you very much for your time and participation. Do you have any further |

| questions or comments? |

| Interview guides for women on the market |

| Introduction |

| 1. Could you introduce yourself? |

| 2. What is it what you do daily? |

| Relationships |

| 1. Could you explain what you do on the market? |

| 2. Could you elaborate on with which actors you collaborate/have to deal with? |

| a. With whom do you have to work? |

| b. Which actors depend on you? |

| c. Why do you need to work with these particular actors? |

| 3. How do you perceive your relationships with others? |

| 4. Could you describe how you develop relationships with other actors? |

| 5. Do you experience any difficulties while developing these relationships? |

| a. If yes, could you describe these difficulties? |

| b. What do you see as the cause of these difficulties? |

| c. And why do you believe that this is the cause? |

| 6. Are there any facilitating factors for developing relationships? |

| a. If yes, could you describe these factors? |

| b. What do you see as the cause of these factors? |

| c. Why do you believe that this is the cause? |

| 7. Could you describe what the goal is of the relationships you develop? |

| Gender |

| 8. What makes your life difficult? |

| 9. To what extent is that based on you being a woman? |

| 10. Could you describe how being a woman affects your work? |

| 11. Could you describe how being a woman affects building relationships within the |

| value chain? |

| Closing of the interview |

| 12. Thank you very much for your time and participation. Do you have any further |

| questions or comments? |

| Interview guide for NGOs and other institutions |

| Introduction |

| 1. Could you introduce yourself? |

| 2. Could you briefly explain what your position is? |

| Relationships |

| 3. Within the agriculture, what types of relationships between actors exist? |

| 4. How do these relationships develop? |

| 5. Could you describe any difficulties that arise while developing such relationships? |

| 6. Could you describe what factors facilitate relationship development? |

| Gender |

| 7. To what extent are relationships affected by gender? |

| 8. Could you describe how being a woman affects the development of relationships |

| within the value chain? |

| Closing of the interview |

| 9. Thank you very much for your time and participation. Do you have any further |

| questions or comments? |

References

- Ellis, A.; Claire, M.; Blackden, M. Gender and Economic Growth in Uganda: Unleashing the Power of Women; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meier zu Selhausen, F. What determines women’s participation in collective action? Evidence from a western Ugandan coffee cooperative. Fem. Econ. 2016, 22, 130–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakire Guma, P. Business in the urban informal economy: Barriers to women’s entrepreneurship in Uganda. J. Afr. Bus. 2015, 16, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.W. Gender: Still a useful category of analysis? Diogenes 2010, 57, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, M.; Benschop, Y. Gender in academic networking: The role of gatekeepers in professorial recruitment. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 51, 460–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.; Zimmerman, D.H. Doing gender. Gend. Soc. 1987, 1, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nentwich, J.C.; Kelan, E.K. Towards a topology of ‘doing gender’: An analysis of empirical research and its challenges. Gend. Work Organ. 2014, 21, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.Y. “Said and done” versus “saying and doing” gendering practices, practicing gender at work. Gend. Soc. 2003, 17, 342–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.Y. Practising gender at work: Further thoughts on reflexivity. Gend. Work Organ. 2006, 13, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.S. Wall Street Women; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, W.J.; Li, S.; Banda, D. Female access to fertile land and other inputs in Zambia: Why women get lower yields. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Kirkby, R.; Kasozi, S. Assessing the impact of bush bean varieties on poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Uganda. Int. Cent. Trop. Agric. 2000, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, T.; Opoku, E. Gender and Sustainability: Learning from Women’s Farming in Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E. Women empowerment and economic development. J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 1051–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, K.; Jones, K.; O’Sullivan, M. Facilitating women’s access to an economic empowerment initiative: Evidence from Uganda. World Dev. 2021, 138, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Madhavan, R. Cooperative networks and competitive dynamics: A structural embeddedness perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Haller, W. The Informal Economy. In The Handbook of Economic Sociology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, L.; Benschop, Y.; Brink, M. Practising Gender When Networking: The Case of University–Industry Innovation Projects. Gend. Work Organ. 2015, 22, 556–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgersson, C. Recruiting managing directors: Doing homosociality. Gend. Work Organ. 2013, 20, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blades, D.; Ferreira, F.H.; Lugo, M.A. The informal economy in developing countries: An introduction. Rev. Income Wealth 2011, 57, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.D. Qualitative Research in Business and Management; Sage Publications Limited: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Buvinić, M.; O’Donnell, M. Gender matters in economic empowerment interventions: A research review. World Bank Res. Obs. 2019, 34, 309–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, A.; Quisumbing, A.; Behrman, J.; Nkonya, E. Understanding the complexities surrounding gender differences in agricultural productivity in Nigeria and Uganda. J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 1482–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfelli, L.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Dohrn, S. Gender and Collective Action: Motivations, Effectiveness and Impact. J. Int. Dev. 2008, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Peterman, A.; Quisumbing, A.; Seymour, G.; Vaz, A. The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Dev. 2013, 52, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, A. African women in the entrepreneurial landscape: Reconsidering the formal and informal sectors. J. Afr. Bus. 2009, 10, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmes, J. The informal economy worldwide: Trends and characteristics. Margin J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2012, 6, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannisson, B.; Ramírez-Pasillas, M.; Karlsson, G. The institutional embeddedness of local inter-firm networks: A leverage for business creation. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2002, 14, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, P.D.; Menguc, B. The implications of socialization and integration in supply chain management. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, C.; Van Bastelaer, T. (Eds.) Understanding and Measuring Social Capital: A Multidisciplinary Tool for Practitioners (Volume 1); World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M.; Narayan, D. Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Res. Obs. 2000, 15, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, A.; Kalmi, P.; Ruuskanen, O.P. Social capital and access to credit: Evidence from Uganda. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Aterido, R.; Beck, T.; Iacovone, L. Access to finance in Sub-Saharan Africa: Is there a gender gap? World Dev. 2013, 47, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Laibson, D.; Sacerdote, B. An economic approach to social capital. Econ. J. 2002, 112, F437–F458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, O.S. A theoretical analysis of the concept of informal economy and informality in developing countries. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 20, 624–636. [Google Scholar]

- Osunsan, O.K. Gender and performance of small scale enterprises in Kampala, Uganda. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2015, 4, 55–65. [Google Scholar]