Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Rural Livelihood: A Case Study of Maple Sap Collecting Households in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Collaborative Forest Management in South Korea

1.2.1. Forest Policy and Rural Community of South Korea

1.2.2. CFM Program of South Korea

1.3. Sustainable Rural Livelihood Framework

2. Materials and Methods

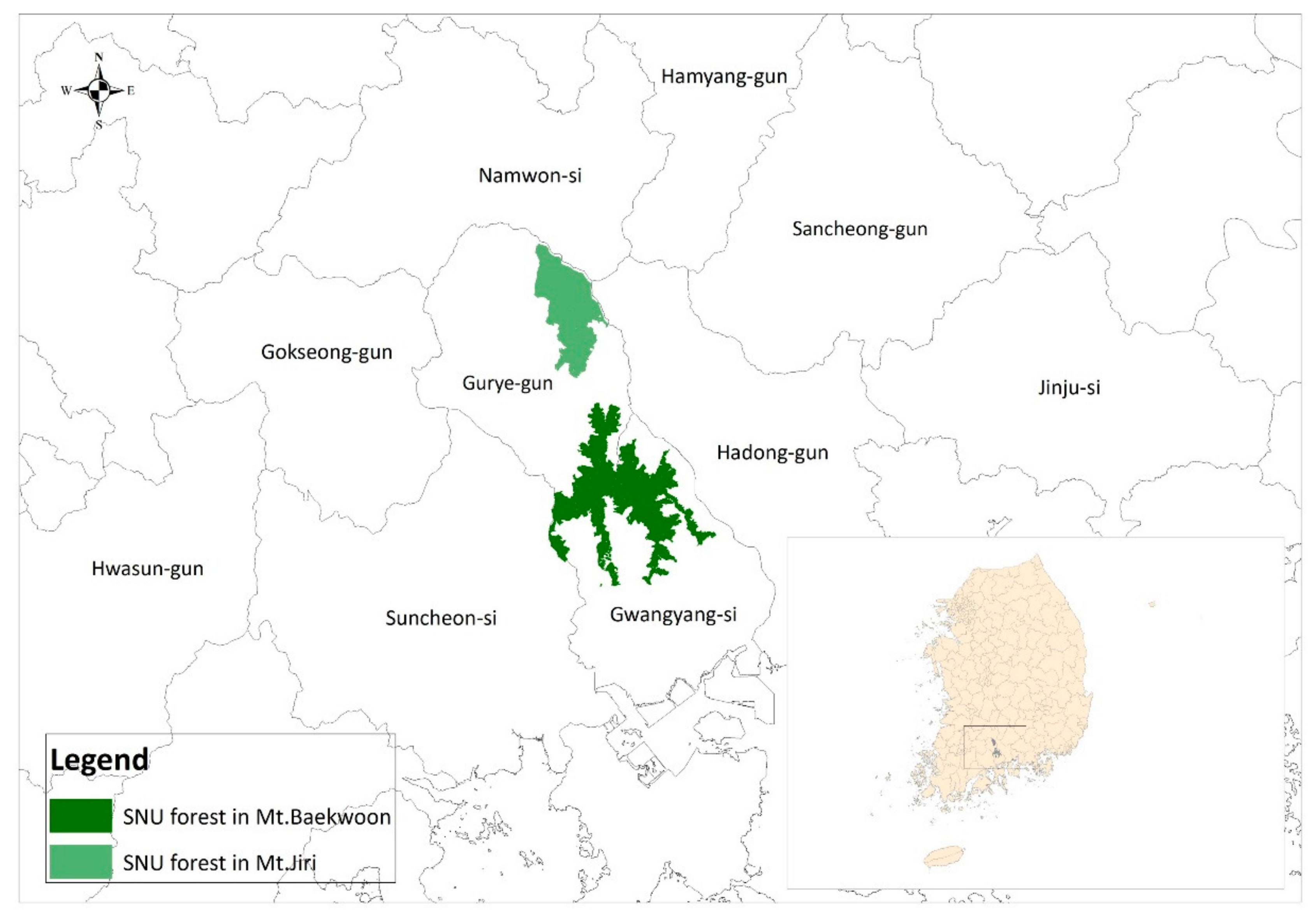

2.1. Study Area and the CFM Arrangement

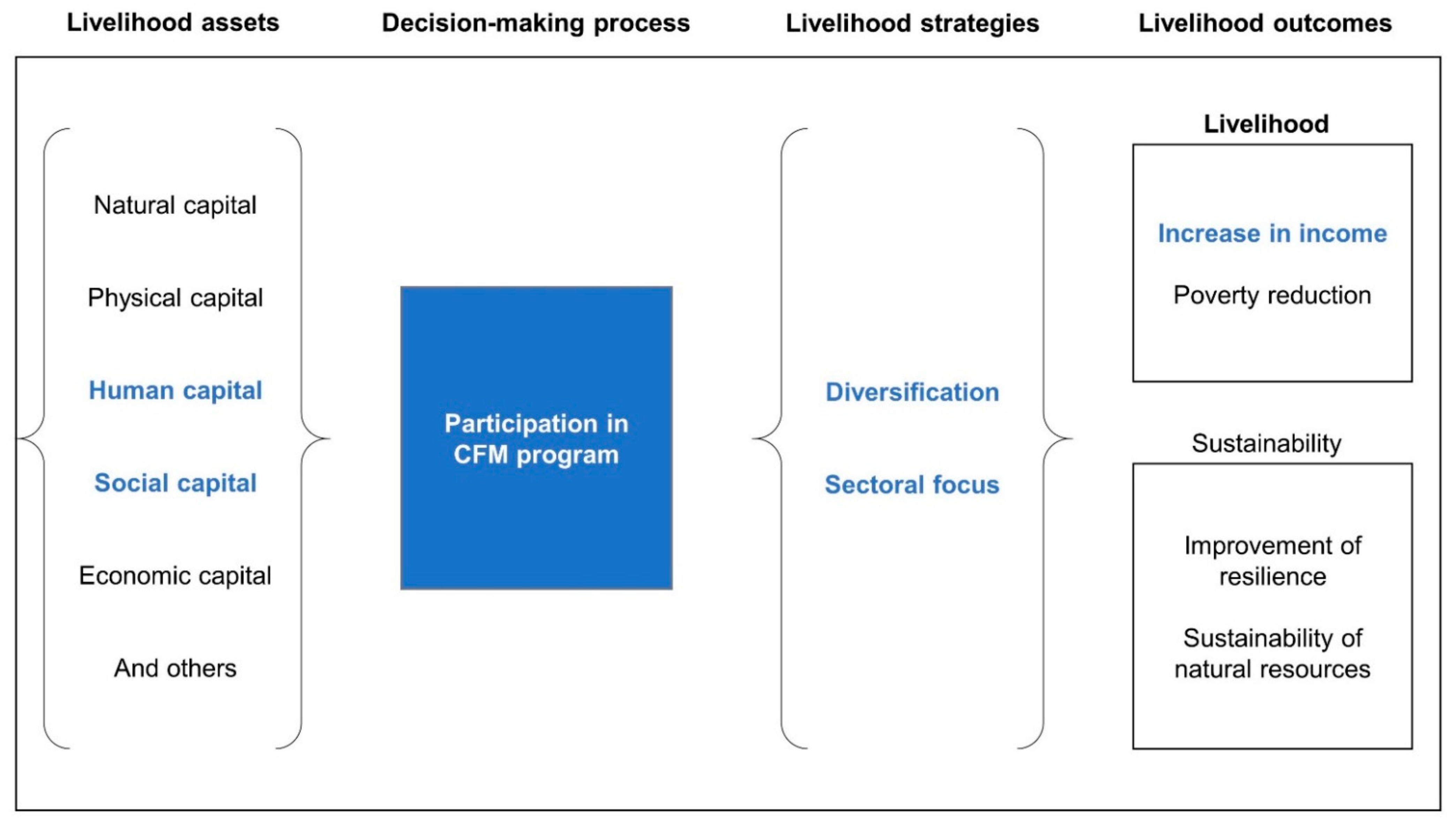

2.2. Conceptual Framework

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Logistic Regression Model

2.3.2. Chi-Squared Test

2.3.3. Ordered Logit Model

2.4. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Respondent Households

3.2. Factors Affecting Household Participation in CFM

3.3. Choice of Household Livelihood Strategy through the CFM Program

3.4. Impact of Participation in CFM on Household Income

4. Discussion

4.1. Forest Management to Increase Income of Forest-Dependent Households

4.2. CFM Program for Sustainable Rural Livelihood

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oksanen, T.; Pajari, B.; Tuomasjukka, T. Forests in Poverty Reduction Strategies: Capturing the Potential; European Forest Institute: Tuusula, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petheram, R.J.; Stephen, P.; Gilmour, D. Collaborative forest management: A review. Aust. For. 2004, 67, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Gronow, J.; Nurse, M.; Malla, Y. Reducing poverty through community based forest management in Asia. J. For. Livelihood 2006, 5, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babulo, B.; Muys, B.; Nega, F.; Tollens, E.; Nyssen, J.; Deckers, J.; Mathijs, E. The economic contribution of forest resource use to rural livelihoods in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlack, C.; Walter, P.L.; Schmerbeck, J.; Tiwari, B. Institutions for sustainable forest governance: Robustness, equity, and cross-level interactions in Mawlyngbna, Meghalaya, India. Int. J. Commons 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shivakoti, G.; Zhu, T.; Maddox, D. Livelihood sustainability and community based co-management of forest resources in China: Changes and improvement. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskoyo, H.; Mohammed, A.; Inoue, M. Impact of community forest program in protection forest on livelihood outcomes: A case study of Lampung Province, Indonesia. J. Sustain. For. 2017, 36, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahut, D.B.; Ali, A.; Behera, B. Household participation and effects of community forest management on income and poverty levels: Empirical evidence from Bhutan. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 61, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzebski, M.P.; Tumilba, V.; Yamamoto, H. Application of a tri-capital community resilience framework for assessing the social–ecological system sustainability of community-based forest management in the Philippines. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, R.B.; Yeo-Chang, Y.; Park, M.S.; Chun, J.-N. Local People’s Participation in Mangrove Restoration Projects and Impacts on Social Capital and Livelihood: A Case Study in the Philippines. Forests 2020, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, S.; Kotani, K.; Kakinaka, M. Enhancing voluntary participation in community collaborative forest management: A case of Central Java, Indonesia. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 150, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyoki, J.K.; Mugwe, J.; Mutundu, K.; Muchiri, M. Factors influencing level of participation of community forest associations in management forests in Kenya. J. Sustain. For. 2016, 35, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, U.B. Beyond money: Does REDD+ payment enhance household′s participation in forest governance and management in Nepal′s community forests? For. Policy Econ. 2017, 80, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Di Falco, S.; Lovett, J.C. Household characteristics and forest dependency: Evidence from common property forest management in Nepal. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoms, C.A. Community control of resources and the challenge of improving local livelihoods: A critical examination of community forestry in Nepal. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1452–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tole, L. Reforms from the ground up: A review of community-based forest management in tropical developing countries. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 1312–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, Y.-C. Use of forest resources, traditional forest-related knowledge and livelihood of forest dependent communities: Cases in South Korea. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.S.; Joo, R.W.; Kim, Y.-S. Forest transition in South Korea: Reality, path and drivers. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, Y.-C.; Choi, J.; de Jong, W.; Liu, J.; Park, M.S.; Camacho, L.D.; Tachibana, S.; Huudung, N.D.; Bhojvaid, P.P.; Damayanti, E.K. Conditions of forest transition in Asian countries. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 76, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, M.S. From Stockholm to Rio de Janeiro: The Road to Sustainable Agriculture; MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, Centre for Research on Sustainable Agriculture: Madras, India, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.K.; Hiremath, B. Sustainable livelihood security index in a developing country: A tool for development planning. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea National Park Service. Statistical Yearbook of National Park; Korea National Park Service: Wonju, Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Service. Statistical Yearbook of Forestry; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Korea, 2020.

- Korea Forest Service. 2th Mountain Village Promotion Master Plan; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Korea, 2017.

- Chun, Y.W.; Tak, K.-I. Songgye, a traditional knowledge system for sustainable forest management in Choson Dynasty of Korea. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 2022–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gevelt, T. Community-based management of Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito and S. Imai) Singer: A case study of South Korean mountain villages. Int. J. Commons 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gevelt, T. The economic contribution of non-timber forest products to South Korean mountain villager livelihoods. For. Trees Livelihoods 2013, 22, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, S.-H.; Youn, Y.-C. Compatibility of Environmental Conservation and Economic Growth using Collaborative Environmental Governance: The case of state forest management. J. Gov. Stud. 2019, 14, 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Sustainable Livelihoods: An Opportunity for the World Commission on Environment and Development; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, M. Household income strategies and natural disasters: Dynamic livelihoods in rural Nicaragua. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel Khatiwada, S.; Deng, W.; Paudel, B.; Khatiwada, J.R.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y. Household livelihood strategies and implication for poverty reduction in rural areas of central Nepal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zheng, H.; Robinson, B.E.; Li, C.; Wang, F. Household livelihood strategy choices, impact factors, and environmental consequences in Miyun reservoir watershed, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, C.; Zhang, H.; Hua, X. Multilevel modeling of rural livelihood strategies from peasant to village level in Henan Province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Bennett, S.J.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y. Agricultural practices and sustainable livelihoods: Rural transformation within the Loess Plateau, China. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 41, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Nijkamp, P.; Xie, X.; Liu, J. A New Livelihood Sustainability Index for Rural Revitalization Assessment—A Modelling Study on Smart Tourism Specialization in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination-Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, M.; Shah, S.J.; Yukun, C.; Rauf, T.; Khan, N.; Shah, S.A.A. Impact of small-to-medium size forest enterprises on rural livelihood: Evidence from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.M.; Kang, H.M.; Kim, J.S. A study on the collection and marketing structure of sap water of Acer mono. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 1998, 87, 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.-G.; Jung, B.-H.; Kim, D.-H. Trends on income inequality and bi-polarization for forest household. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2017, 106, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-G.; Kim, B.-K.; Kim, D.-H. Analysis of Forestry Household Income Inequality using Gini Coefficient Decomposition by Income Sources. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2019, 108, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.-H.; Roh, T.; Youn, Y.-C. Impact of Forestry Characteristics and Regional Characteristics on Income Determination in Forestry: Focusing on Mountain Village and Non-Mountain Village. Reg. Ind. Rev. 2018, 41, 203–236. [Google Scholar]

- Min, K.-T.; Kim, M.-E. A study on population change and projection in Korea Mountainous area. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2014, 103, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chang, C.; Bae, J.S.; Seol, A. A Sudy on Population Change and Projection in Korean Mountainous Area. J. Korean Soc. Rural Plan. 2019, 25, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patenaude, G.; Lewis, K. The impacts of Tanzania′s natural resource management programmes for ecosystem services and poverty alleviation. Int. For. Rev. 2014, 16, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | Coding Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Participation | Participation in the agreement for collecting maple sap in the SNU Forest | 1 if respondent’s household participates in the agreement on maple sap collection in the SNU Forest, otherwise 0 | |

| Explanatory variables | Human capital | Age | Age of household head | Numerical age of head of respondent’s household |

| Female-headed | Female-headed household living alone without spouse and children | 1 if respondent belongs to a female-headed household, otherwise 0 | ||

| Family size | Number of family members | Number of family members in respondent’s household | ||

| Social capital | Length of residence | Length of residence in the village | Number of years respondent has resided in the village | |

| Variable | Definition | Coding Value |

|---|---|---|

| Participation | Participation in the agreement on maple sap collection in the SNU Forest | 1 if respondent’s household participates in the agreement on maple sap collection in the SNU Forest, otherwise 0 |

| Diversification | Diversification from more than two income sources | 1 if income from more than two income sources constitutes the income of the respondent’s household, otherwise 0 |

| Variable | Definition | Coding Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Income | Annual household income level |

|

| Explanatory variable | Livelihood strategy | Type of livelihood strategy group decided by diversification and household participation in the agreement on maple sap collection in the SNU Forest |

|

| Control variables | Age | Age of household head | Numerical age of head of respondent’s household |

| Female-headed | Female-headed household living alone without spouse and children |

| |

| Family size | Number of family members | Number of family members in respondent’s household |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human capital | Age (Numerical age) | 67.7 | 13.6 | 24 | 99 |

| Female-headed (Female-headed = 1) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | |

| Family size (Number of members) | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1 | 9 | |

| Social capital | Length of residence (Number of years) | 46.5 | 24.8 | 1 | 98 |

| Income source | Forestry (%) | 22.3 | 31.8 | 0 | 100 |

| Agriculture (%) | 16.7 | 32.2 | 0 | 100 | |

| Tourism (%) | 11.9 | 26.2 | 0 | 100 | |

| Labor and other business (%) a | 9.3 | 26.7 | 0 | 100 | |

| Other income sources (%) b | 39.7 | 43.1 | 0 | 100 | |

| Participation (participation in the agreement = 1) | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Z Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.045 *** | −3.07 |

| Female-headed | −0.684 * | −1.78 |

| Family size | 0.144 | 1.09 |

| Length of residence | 0.023 *** | 3.11 |

| Constant | 1.339 | 1.40 |

| Obs. | 257 | |

| LR chi2 (prob > chi2) | 33.37(0.000) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.098 | |

| Log likelihood | −153.652 | |

| Non-CFM Participating Households | CFM Participating Households | Total Households | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Households who chose the sectoral focus strategy | 108 | 15 | 123 |

| Households who chose the diversification strategy | 52 | 82 | 134 |

| Total households | 160 | 97 | 257 |

| Household Income Level | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | under 10 million KRW a | 127 | 49.4 |

| 2 | between 10 to 20 million KRW | 55 | 21.4 |

| 3 | between 20 to 30 million KRW | 18 | 7.0 |

| 4 | between 30 to 40 million KRW | 15 | 5.8 |

| 5 | between 40 to 50 million KRW | 10 | 3.9 |

| 6 | more than 50 million KRW | 32 | 12.5 |

| Total | 257 | 100.00 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Z Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Livelihood strategy a | CFM participating diversification | 0.814 ** | 2.55 |

| CFM participating sectoral focus | −0.122 | −0.22 | |

| Non-CFM participating diversification | 1.315 *** | 3.68 | |

| Age | −0.074 *** | −6.35 | |

| Female-headed | −1.751 *** | −4.25 | |

| Family size | 0.216 * | 1.74 | |

| /cut1 | −4.643 | ||

| /cut2 | −3.184 | ||

| /cut3 | −2.619 | ||

| /cut4 | −2.087 | ||

| /cut5 | −1.667 | ||

| Obs. | 257 | ||

| LR chi2 (prob > chi2) | 148.42(0.000) | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.204 | ||

| Log likelihood | −289.710 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S.-H.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Rural Livelihood: A Case Study of Maple Sap Collecting Households in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041594

Park S-H, Yeo-Chang Y. Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Rural Livelihood: A Case Study of Maple Sap Collecting Households in South Korea. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041594

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, So-Hee, and Youn Yeo-Chang. 2021. "Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Rural Livelihood: A Case Study of Maple Sap Collecting Households in South Korea" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041594

APA StylePark, S.-H., & Yeo-Chang, Y. (2021). Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Rural Livelihood: A Case Study of Maple Sap Collecting Households in South Korea. Sustainability, 13(4), 1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041594