When Unfair Trade Is Also at Home: The Economic Sustainability of Coffee Farms

Abstract

1. Introduction

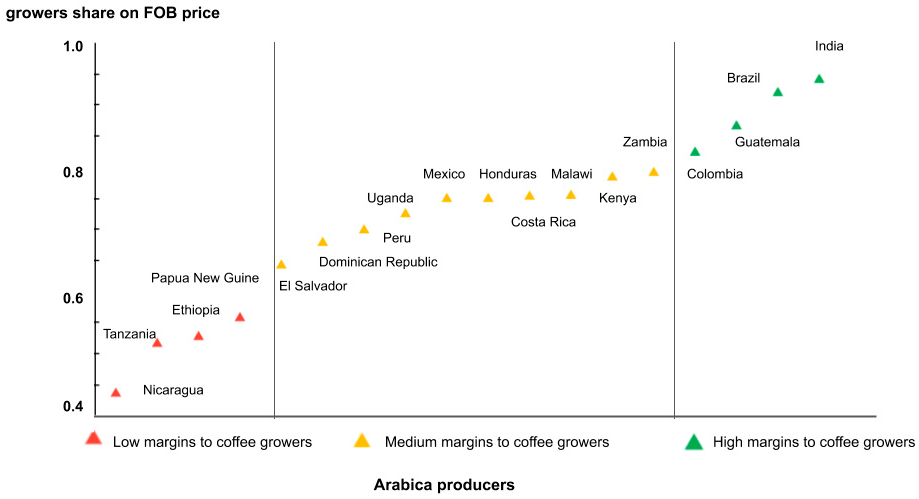

2. Unfair Trade Practices: Differences in Margins Obtained by Coffee Farmers

3. Data

3.1. Dependent Variable: Price Ratio

3.2. Explanatory Variables

3.3. Control Variables

4. Model

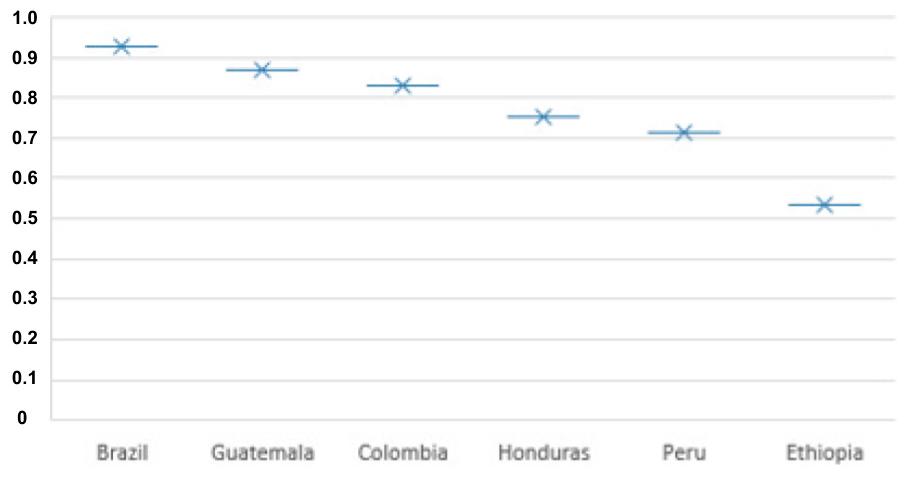

5. Results and Discussion

Institutions and Infrastructure

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sachs, J.D.; Cordes, K.Y.; Rising, J.; Toledano, P.; Maennling, N. Ensuring Economic Viability and Sustainability of Coffee Production. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICO. Historical Data on the Global Coffee Trade. 2020. Available online: http://www.ico.org/new_historical.asp?section=Statistics (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Daviron, B.; Ponte, S. The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Daviron, B.; Ponte, S. Le Paradoxe du Café; Quae, Ed.; Di Marcantonio: Versailles, France, 2007; pp. 877–903. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, B.; Giovannucci, D.; Varangis, P. Coffee Markets: New Paradigms in Global Supply and Demand. SSRN Electron. J. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, Z.; Knudson, C.; Rhiney, K. Will COVID-19 be one shock too many for smallholder coffee livelihoods? World Dev. 2020, 136, 105172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICO. Coffee Development Report 2019 Growing for Prosperity Economic Viability as the Catalyst for a Sustainable Coffee Sector. 2019. Available online: https://www.internationalcoffeecouncil.org/eng/coffee-development-report.php (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Koning, B.J.; Calo, M.; Jongeneel, R.A. Fair Trade in Tropical Crops is Possible; Wageningen University: Wageninen, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, A.; Chavas, J.-P. Responding to the coffee crisis: What can we learn from price dynamics? J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 85, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICO. Survey on the impact of low coffee prices on exporting countries. In Proceedings of the International Coffee Council 124th Session, Nairobi, Kenya, 25–29 March 2019; Available online: http://www.ico.org/documents/cy2018-19/Restricted/icc-124-4e-impact-low-prices.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Voora, V.; Bermudez, S.; Larrea, C. Global Market Report: Coffee. 2019. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/ssi-global-market-report-coffee.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Gomez, M.I.; Lee, J.; Koerner, J. Do retail coffee prices rise faster than they fall? Asymmetric price transmission in France, Germany and the United States. J. Int. Agric. Trade Dev. 2010, 6, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, D.R.; Santana, J.A. Asymmetry in farm to retail price transmission: Evidence from Brazil. Agribusiness 2002, 18, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivonos, E. The Impact of Coffee Market Reforms on Producer Prices and Price Transmission. World Bank Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2004, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukanima, B.; Swaray, R. Market Reforms and Commodity Price Volatility: The Case of East African Coffee Market. World Econ. 2013, 37, 1152–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibtag, E.; Nakamura, A.O.; Nakamura, E.; Zerom, D. Cost Pass-Through in the U.S. Coffee Industry. SSRN Electron. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, J.; Ménard, C.; Sexton, R.J.; Swinnen, J.; Vandevelde, S. Unfair Trading Practices in the Food Supply Chain: A Literature Review on Methodologies, Impacts and Regulatory Aspects (No. 607491); KU Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Tackling Unfair Trading Practices in the Business-to-Business Food Supply Chain. Communication of the Commission, 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52014DC0472 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- USDA. Coffee: World Markets and Trade. 2019. Available online: https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/m900nt40f?locale=en (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Sexton, R. Unfair trade practices in the food supply chain: Defining the problem and the policy issues. In Unfair Trading Practices in the Food Supply Chain: A Literature Review on Methodologies; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; pp. 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Saes, M.S.M. Strategies for Differentiation and Quasi-Rent Appropriation in Agriculture: The Small-Scale Production; Annablume: Berlin, Germany, 2010; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, R.L.F.; Mattos, F. The reaction of coffee futures prices to crop reports. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2017, 53, 2361–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisset, J. Unfair Trade? The Increasing Gap between World and Domestic Prices in Commodity Markets during the Past 25 Years. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1998, 12, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, D.; Koekoek, F.J. The State of Sustainable Coffee; IISD, UCTAD, ICO: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Fitter, R.; Kaplinsky, R. Who Gains When Commodities are Decommodified; Institute of Development Studies (IDS), University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shilinde, J.S.M.; Bee, F. Does domestic trade policy change matters for international price volatility? Empirical evidence from coffee price in Tanzania. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Gemech, F.; Struthers, J. Coffee price volatility in Ethiopia: Effects of market reform programmes. J. Int. Dev. 2007, 19, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanja, A.M.; Kuyvenhoven, A.; Moll, H.A. Economic Reforms and Evolution of Producer Prices in Kenya: An ARCH-M Approach. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2003, 15, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikos, D. Revisiting the Role of Institutions in Transformative Contexts: Institutional Change and Conflicts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, C.; Valceschini, E. New institutions for governing the agri-food industry. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, C. Organization and governance in the agrifood sector: How can we capture their variety? Agribusiness 2017, 34, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.A.; Rashid, S.; Lemma, S.; Kuma, T. Market Institutions and Price Relationships: The Case of Coffee in the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LDC. Toward a Sustainable Coffee Value Chain. 2018. Available online: https://www.ldc.com/wp-content/uploads/LDC_Coffee_Report_2018-1.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- Hütz, A. Impact of Supply Chain Relations on Farmers Income Ethiopia. Suedwind-Institut, 2020. Available online: https://www.suedwind-institut.de/files/Suedwind/Publikationen/2020/2020-10%20Impact%20of%20supply%20chain%20relations%20on%20farmers%20income%20in%20Ethiopia.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- World Bank. GovData 360 Indicators. 2020. Available online: https://govdata360.worldbank.org/topics (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Panhuysen, S.; Pierrot, J. Barómetro de Café. 2014. Available online: https://www.federaciondecafeteros.org/static/files/5Barometro_de_cafe2014.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Panhuysen, S.; Pierrot, J. Coffee Barometer 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.hivos.org/assets/2018/06/Coffee-Barometer-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- UNDP. Human Development Reports. 2020. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/data (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Oliveira, G.M.; Zylbersztajn, D. Can contracts substitute hierarchy? Evidence from high-quality coffee supply in Brazil. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eufemia, L.; Bonatti, M.; Sieber, S.; Schröter, B.; Lana, M.A. Mechanisms of Weak Governance in Grasslands and Wetlands of South America. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, F.R.; Boland, M. Strategy-structure alignment in the world coffee industry: The case of cooxupe. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2009, 31, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICO/CFC. Study of Marketing and Trading Policies and Systems in Selected Coffee Producing Countries. Country Profile: Guatemala. 2020. Available online: http://www.ico.org/projects/countryprofiles/countryprofileGUATEMALAe.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Tay, K. Coffee Annual. Guatemala. USDA. Foreign Agricultural Service. 15 November 2020. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Coffee%20Annual_Guatemala%20City_Guatemala_5-15-2019.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- World Bank/LAC. Unlocking Central America’s Export Potential. Finance and Private Sector Development Department Central America Country Management Unit Latin America and the Caribbean Region. 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/27216/750700WP0v200B0ses020120vF00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Gonzalez-Perez, M.; Gutierrez-Viana, S. Cooperation in coffee markets: The case of Vietnam and Colombia. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2012, 2, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Palma, J.U. Coffee, Quality and Origin within a Developing Economy: Recent Findings from the Coffee Production of Honduras. Working Paper. 15 November 2020. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/download/38445552/Quality_and_Origin_of_Coffee_within_a_Developing_Economy.docx (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Sipa. Improving the Performance of the Peruvian Coffee Supply Chain with New Digital Technologies. 2017. Available online: https://sipa.columbia.edu/file/5065/download?token=QbaFVl7V (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- PNUD. Plan Nacional de Acción del Café Peruano. Una Propuesta de Política Para un Caficultura Moderna, Competitiva y Sostenible. Documento Preliminar. 2018. Available online: https://www.minagri.gob.pe/portal/images/cafe/PlanCafe2018.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Andersson, C.; Bezabih, M.; Mannberg, A. The Ethiopian Commodity Exchange and spatial price dispersion. Food Policy 2017, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction cost economics: The comparative contracting perspective. J. Econ. Behave. Organ. 1987, 8, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Component variables | ||

| Farm-gate price | Unit value paid to coffee growers for the green bean in exporting countries | Currency/Weight: US cents/lb |

| FOB price | Unit value for the green bean exportation | Currency/Weight: US cents/lb |

| Dependent variable | ||

| Price ratio | Growers share of value in the FOB price | 0–1 (0 = Unfair trade; 1 = Fairer trade) |

| Variables | Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Control variables | ||

| Inflation, consumer prices | Change in the cost of a given basket of goods and services to the average consumer | Annual (%) |

| GDP per capita | Gross Domestic Product divided by midyear population | Current US$ |

| Official exchange rate | Exchange rate determined by national authorities or to the rate determined in the legally sanctioned exchange market | Local Currency Unit per US$, period average |

| HDI | Human Development Index | Index |

| Rural population | People living in rural areas as defined by national statistical offices. It is calculated as the difference between total population and urban population. | % of total population |

| Institutional variable | ||

| Property rights | Response to the WEF survey question “In your country, to what extent are property rights, including financial assets, protected?” | 1–7 (1 = not at all; 7 = to a great extent) |

| Infrastructure variables | ||

| Access to electricity | Access to electricity | % of population |

| Quality of port infrastructure * | Business executives’ perception of their country’s port facilities according to the WEF survey. | 1–7 (1 = extremely underdeveloped; 7 = efficient by international standards). |

| Quality of roads | Response to the WEF survey question “In your country, what is the quality (extensiveness and condition) of road infrastructure?” | 1–7 (1 = extremely poor; 7 = extremely good—among the best in the world) |

| Descriptive Statistics | Mean | Standard-Deviation (SD) | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabica price ratio | 0.76 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.10 |

| Inflation | 6.18 | 8.28 | −27.78 | 44.35 |

| GDP per capita | 4705.29 | 3453.98 | 244.28 | 13,245.61 |

| Exchange Rate | 365.07 | 817.75 | 1.67 | 3054.12 |

| Human development index (HDI) | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.75 |

| Rural population | 40.05 | 23.23 | 13.95 | 83.88 |

| Property rights | 3.97 | 0.35 | 3.31 | 4.68 |

| Access to electricity | 81.94 | 22.21 | 23.00 | 99.71 |

| Quality of port | 3.59 | 0.75 | 2.34 | 5.33 |

| Quality of the roads | 3.00 | 0.62 | 0.40 | 4.00 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Arabic Price Ratio | Arabic Price Ratio |

| Inflation | −0.000190 | |

| (0.00133) | ||

| GDP per capita | 1.16 × 105 * | 1.12 × 105 ** |

| (6.95 × 106) | (5.46 × 106) | |

| Exchange Rate | 1.02 × 106 | |

| (1.36 × 105) | ||

| Human development index (HDI) | −0.736 | −0.603 *** |

| (0.530) | (0.230) | |

| Rural population | −0.000875 | |

| (0.00294) | ||

| Property rights | 0.0908 ** | 0.0941 *** |

| (0.0357) | (0.0349) | |

| Access to electricity | 0.00634 *** | 0.00658 *** |

| (0.00133) | (0.00111) | |

| Quality of ports | 0.00616 | |

| (0.0163) | ||

| Quality of the roads | 0.0402 * | 0.0400 ** |

| (0.0215) | (0.0179) | |

| Constant | 0.190 | 0.0603 |

| (0.501) | (0.179) | |

| Observations | 60 | 60 |

| R-squared | 0.703 | 0.703 |

| Number of ID Country | 6 | 6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lerner, D.G.; Pereira, H.M.F.; Saes, M.S.M.; Oliveira, G.M.d. When Unfair Trade Is Also at Home: The Economic Sustainability of Coffee Farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031072

Lerner DG, Pereira HMF, Saes MSM, Oliveira GMd. When Unfair Trade Is Also at Home: The Economic Sustainability of Coffee Farms. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031072

Chicago/Turabian StyleLerner, Daniel Grandisky, Helder Marcos Freitas Pereira, Maria Sylvia Macchione Saes, and Gustavo Magalhães de Oliveira. 2021. "When Unfair Trade Is Also at Home: The Economic Sustainability of Coffee Farms" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031072

APA StyleLerner, D. G., Pereira, H. M. F., Saes, M. S. M., & Oliveira, G. M. d. (2021). When Unfair Trade Is Also at Home: The Economic Sustainability of Coffee Farms. Sustainability, 13(3), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031072