Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Development and Sustainable Tourism Marketing

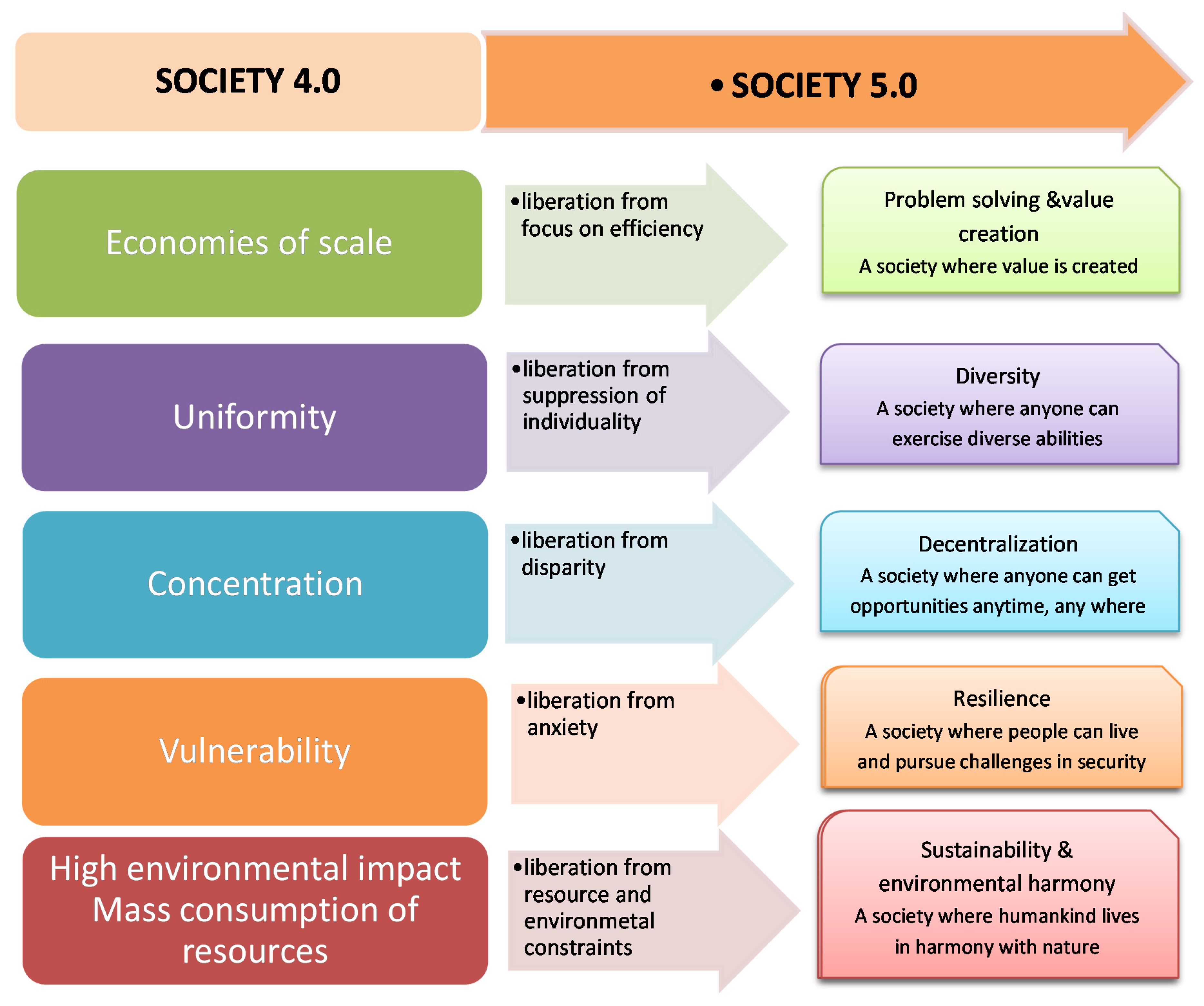

2.2. Society 5.0 Idea

- creating a global future through Society 5.0,

- enabling solutions using global data,

- promoting cooperation at global and cross-sectoral level,

- supporting human resources to undertake science, technology, and innovation (STI) efforts in support of the Sustainable Development Goals.

2.3. Social Media in Tourism

- social presence/media richness,

- self-presentation and self-disclosure.

- blogs and microblogs (e.g., Twitter),

- social networks (e.g., Facebook, Google+),

- professional social networking sites (e.g., LinkedIn),

- cooperation networks/shared projects (e.g., Wikipedia),

- Internet forums (e.g., Globetrotter, Fly4Free, Lonely Planet travel forums),

- content communities (e.g., YouTube, Vimeo, Pinterest)

- rating services and portals (e.g., TripAdvisor, Booking, HolidayCheck),

- virtual worlds, social (e.g., Second Life),

- virtual game worlds (e.g., World of Warcraft).

2.4. The Travel Experience of Different Generations

2.4.1. Baby Boomers

2.4.2. Generation X

2.4.3. Generation Y

2.4.4. Generation Z

- RQ1: What is the frequency of using different social media depending on the generation?

- RQ2: What are the behaviours of particular generations in social media in terms of planning a holiday?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures, Data Collection, and Sample

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Activity of Tourists of Various Generations in Social Media

4.1.1. The Frequency of Using Social Media Depending on the Generations

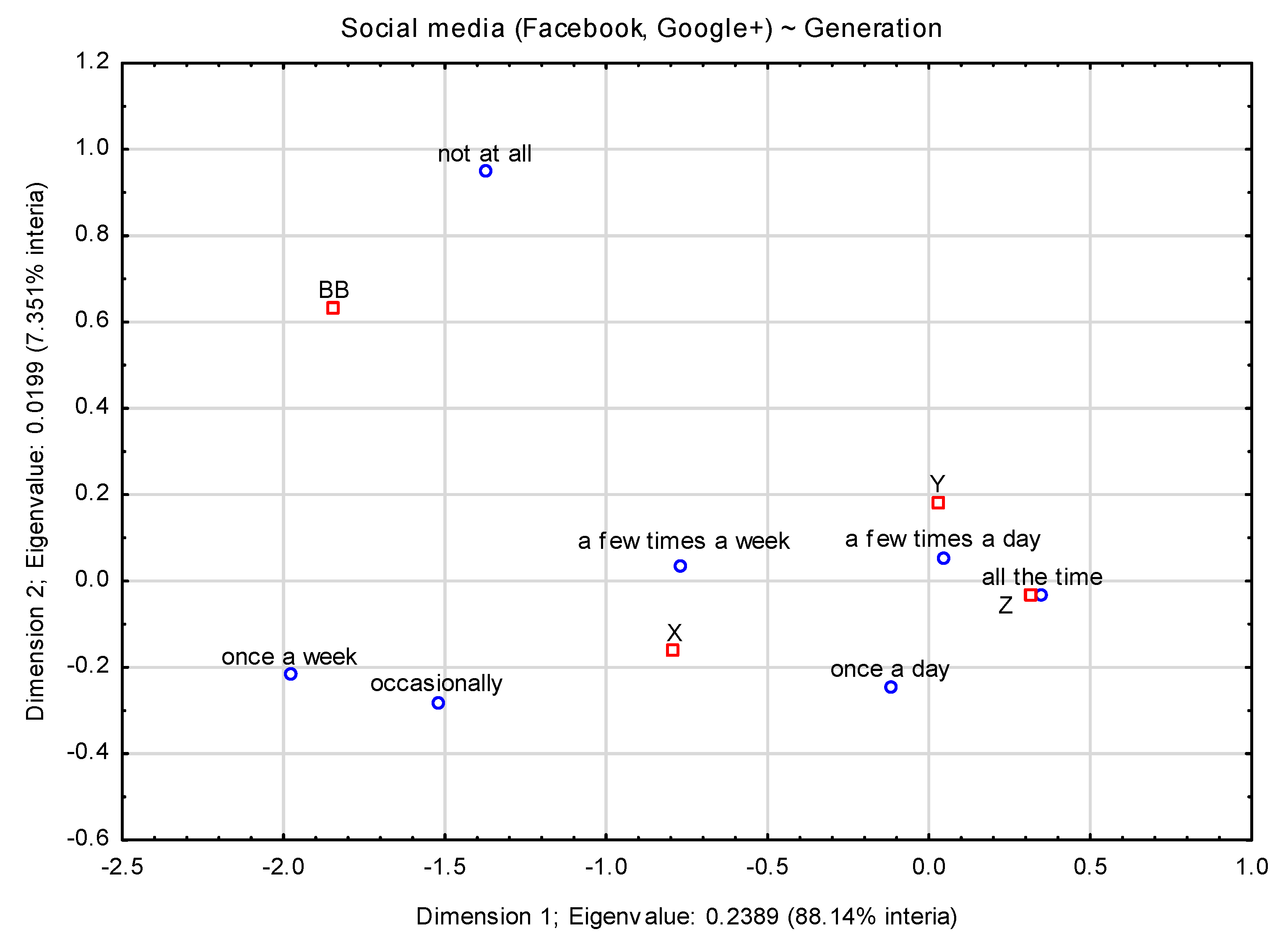

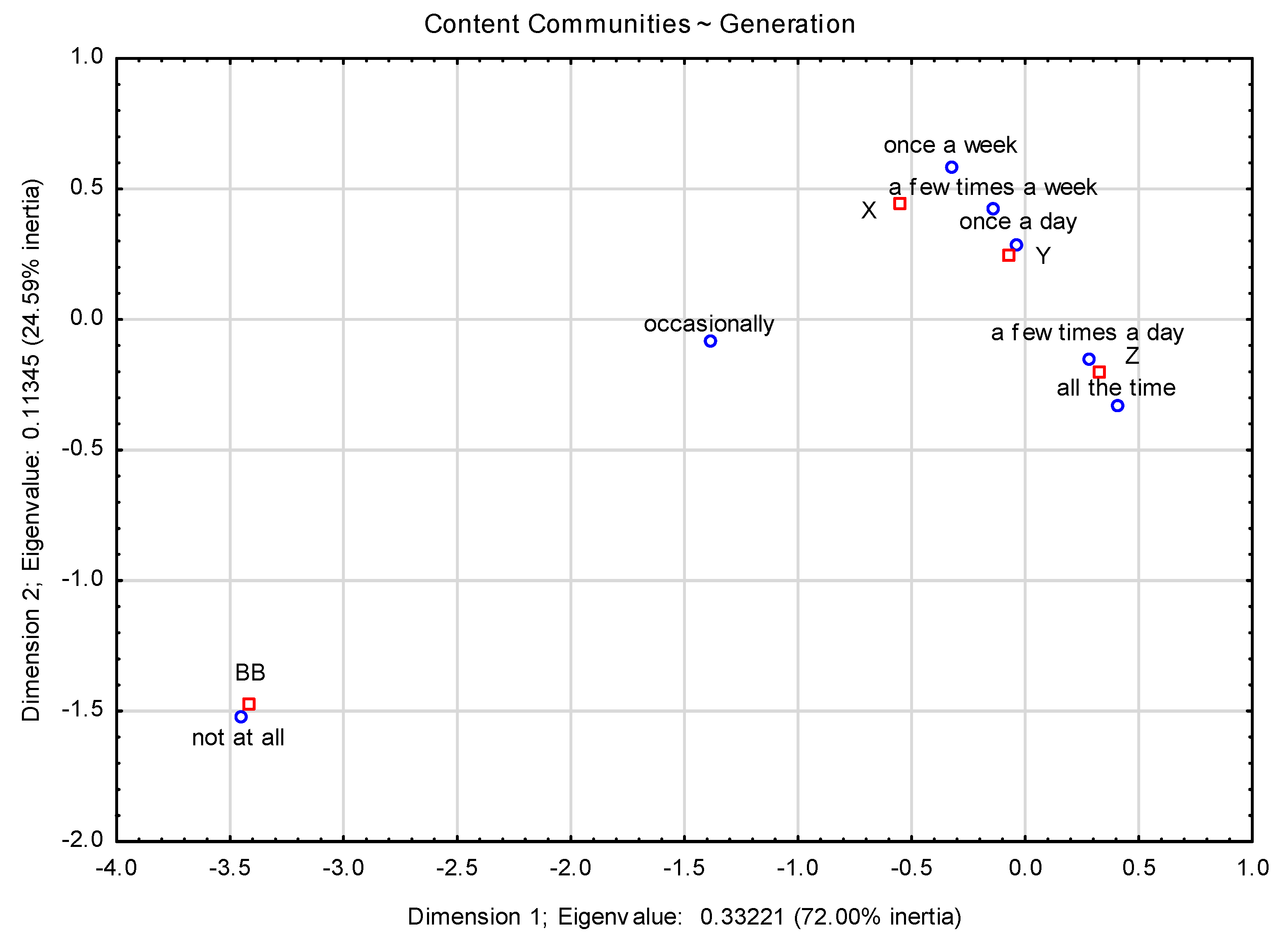

4.1.2. Relationships between Different Types of Social Media

Travel forums = I don’t use them at all => Rating portals = I use them occasionally (support = 21.4%, trust = 46.2%)

Social networks = a few times a day => Content communities = all the time (support = 18.4%, trust = 44%)

- for V1.3 and V1.5 (p = 0.00043, the correlation coefficient for Generations X and BB is not significantly different from zero, for Generation Y 0.33 and for Z 0.22)

- for V1.4 and V1.2 (p < 0.00001, the correlation coefficient for the BB generation is not significantly different from zero, for X 0.32, for Y 0.42, for Z 0.24).

4.2. Using SM at the Planning Stage of the Trip

- I check opinions/stories on places I want to visit on social media (1.2 ± 0.84).

- Positive opinions and comments in social media encourage me to go on holiday (1.12 ± 0.9).

- In social media, I am looking for information about hindrances and problems that may arise in the places I intend to visit (1.06 ± 0.81).

- I use social media to learn about the history and culture of tourist places (0.94 ± 0.93).

- I use social media to plan a trip (0.82 ± 0.97).

- Negative opinions and comments in social media make me resign from a holiday (0.52 ± 1.01).

- I use short term apartment rentals (e.g., Airbnb) (−0.07 ± 1.4).

- I use social media to establish relationships with the local community (−0.17 ± 1.26).

Generational and Gender Influences

- In case of the statement that positive opinions and comments on social media encourage to go on holidays, Generation Z and BB agreed with it more than Generation X and Y. Comparative analysis between generations confirmed that there is a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of Generations Z and X (p = 0.013), as well as Z and Y (p = 0.033). The gender analysis showed significant differences between the opinions of women and men (p = 0.001), where women expressed their positive agreement with the discussed view more often than men. In this way, the Hypothesis 2.1 was confirmed.

- Respondents of all generations agree that they use SM to learn about the history of these places and look for information about hindrances in the places they plan to go to on holiday. There were no generational or gender differences. Thus, the Hypotheses 2.2 and 2.3 were rejected.

- In turn, in the case of the role of negative comments, Generation Z declares their greatest share in the respondent’s resignation. Comparative analysis between the generations confirmed that there is a statistically significant difference between the mean scores for Generations Z and Y (p = 0.006). The gender analysis did not show any statistically significant differences. Thus, the Hypothesis 2.4 was partially accepted.

- Generally, all respondents of Generations X, Y, and Z use SM to plan their trip, while Generation BB maintains a neutral attitude in this respect. The Kruskal–Wallis test did not show statistically significant differences here. Women more often than men declare a positive attitude towards using SM to plan a trip. A statistically significant difference was observed in this respect (p = 0.001). Thus, the Hypothesis 2.5 was partially accepted.

- Respondents of all generations do not use SM to establish relationships with the local community, and representatives of the BB generation are more assertive in this opinion. There were no statistically significant differences, neither at the generational nor gender level. Thus, the Hypothesis 2.6 was rejected.

- In general, all respondents agree with the opinion that they check opinions/stories on the places they want to visit on social media. The BB generation agrees with this statement much less frequently than the other generations. Comparative analysis between the generations confirmed that there is a statistically significant difference between the mean scores for Generations Z and BB (p = 0.03). In turn, a comparative analysis by gender revealed that women much more often than men check the opinions about places they want to visit in SM (p = 0.002). Thus, the Hypothesis 2.7 was accepted.

- The greatest support for the use of short-term apartment rentals is declared by Generation X. Generations Y and Z maintain a neutral attitude, and generation BB—negative. Comparative analysis between generations confirmed that there is a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of Generations X and BB (p = 0.002), Y and BB (p = 0.007), as well as Z and BB (p = 0.005). Men more often than women declared a positive opinion on the use of short-term apartment rentals, but there were no statistically significant differences between these groups. Thus, the Hypothesis 2.8 was partially confirmed.

5. Conclusions, Limits of Research, and Future Research

- The BB generation differs significantly from Generation Z in terms of checking the opinion of the place they want to visit in SM and the use of short-term apartment rentals (e.g., Airbnb), as they declare these behaviours less frequently than Generation Z. Both negative and positive comments in SM about tourist destinations are treated by the BB generation similarly as i case of Generations X, Y, and Z.

- Generation X differs significantly from Generation Z only in terms of behaviour related to making decisions based on positive comments, as it shows less enthusiasm in this respect than Generation Z. Significant differences were also noted in the field of short-term apartment rentals by Generation X, compared to BB, where Generation X declares a more favourable attitude to this behaviour. In the case of other behaviours, Generation X does not differ from the examined generations.

- In terms of behaviour related to making decisions based on positive and negative comments, Generation Y clearly differs from Generation Z. In both of these behaviours, a more neutral attitude is declared than in case of Generation Z, for which these comments are more important. Representatives of this generation also declare the use of short-term apartment rentals (e.g., Airbnb) the most. This behaviour significantly distinguishes the representatives of Generation Y from the representatives of Generations BB and Z.

- Generation Z is most in favour of making decisions based on positive comments, and in this respect, it differs from Generations X and Y but does not differ from generation BB. In the case of negative comments, only Generation Y declares a more critical attitude than Generation Z. In terms of the use of short-term apartment rentals and checking the opinion of tourist destinations in SM, Generation Z is characterised by a neutral attitude, similar to Generations X and Y, but more favourable than generation BB.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azam, M.; Alam, M.M.; Haroon Hafeez, M. Effect of tourism on environmental pollution: Further evidence from Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiroishi, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Suzuki, N. Better actions for society 5.0: Using AI for evidence based policy making that keeps humans in the loop. Computer 2019, 52, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO 2020. AlUla Framework for Inclusive Community Development through Tourism. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284422159 (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Wu, T.-P.; Wu, H.-C.; Liu, S.-B.; Hsueh, S.-J. The relationship between international tourism activities and economic growth: Evidence from China’s economy. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresta, S.; Bonin, B.B. Perspectives on Social Media Marketing; Course Technology, Cengage Learning PTR: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berthon, P.R.; Pitt, L.F.; Plangger, K.; Shapiro, D. Marketing meets Web 2.0, social media, and creative consumers: Implications for international marketing strategy. Bus. Horiz. 2012, 55, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Magnini, V.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Information Technology and Consumer Behaviour in Travel and Tourism: Insights from Travel Planning Using the Internet. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębski, M.; Krawczyk, A.; Dworak, D. Wzory zachowań turystycznych przedstawicieli Pokolenia Y. Stud. Prace Kol. Zarz. Finans. 2019, 172, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- AARP Reaserch. 2020 Travel Trends, January. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/life-leisure/2019/2020-travel-trends.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00359.001.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- UNWTO 2020a. One Planet Vision for a Responsible Recovery of the Tourism Sector, One Planet Sustainable Tourism Programme. Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/sustainable-tourism/covid-19-responsible-recovery-tourism (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- McCrindle, M. The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations, 3rd ed.; McCrindle Research Pty Ltd.: Norwest, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grenčíková, A.; Vojtovič, S. Relationship of generations X, Y, Z with new communication technology. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2017, 15, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Starcevic, S.; Konjikusic, S. Why Millenials As Digital Travelers Transformed Marketing Strategy in Tourism Industry. In International Thematic Monograph Tourism in Function of Development of the Republic of Serbia, Tourism in the Era of Digital Transformation; University of Kragujevac: Kragujevac, Serbia, 2018; pp. 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Dolot, A. The characteristics of Generation, Z. E Mentor 2018, 74, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP & UNWTO Making Tourism More Sustainable—A Guide for Policy Makers. 2005, pp. 11–12. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Rosato, P.F.; Caputo, A.; Valente, D.; Pizzi, S. 2030 Agenda and sustainable business models in tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 106978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council 2020. To Recovery & Beyond: The Future of Travel & Tourism in the Wake of COVID-19—September 2020. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/To-Recovery-Beyond (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Grilli, G.; Tyllianakis, E.; Luisetti, T.; Ferrini, S.; Turner, R.K. Prospective tourist preferences for sustainable tourism development in Small Island Developing States. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Itscontexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vinzenz, F.; Priskin, J.; Wirth, W.; Ponnapureddy, S.; Ohnmacht, T. Marketing sustainable tourism: The role of value orientation, well-being and credibility. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 2, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO 2020b. Understanding Domestic Tourism and Seizing Its Opportunities, Unwto Briefing Note—Tourism and COVID-19, ISSUE 3. 2020. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284422111 (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Liao, Y.-L.; Tsai, C.-F. Analyzing the important implications of tourism marketing slogans and logos in Asia Pacific nations. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emarketer.com. US Travel Ad Spending Will Plunge by 41.0% This Year. 24 September 2020. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/us-travel-ad-spending-will-plunge-by-41-0-this-year (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- The Future of Travel Advertising: The 2020 Report on Travel Advertising in Europe, Sojern. Available online: https://www.sojern.com/travel-advertising-report-2020-eu/ (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- US Travel Digital Ad Spending. 2020. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/us-travel-digital-ad-spending-2020 (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- MDG Advertising. Vacationing the Social Media Way. 30 May 2018. Available online: https://www.mdgadvertising.com/marketing-insights/infographics/vacationing-the-social-media-way-infographic/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Du Vall, M. Super inteligentne społeczeństwo skoncentrowane na ludziach, czyli o idei społeczeństwa 5.0 słów kilka. Państwo Społecz. 2019, 19, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 5th Science and Technology Basic Plan, Government of Japan. January 2016. Available online: http://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/english/basic/5thbasicplan.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Shiroishi, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Suzuki, N. Society 5.0: For human security and well-being. Computer 2018, 51, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tworóg, J.; Mieczkowski, P. Krótka Opowieść o Społeczeństwie 5.0, Czyli Jak Żyć i Funkcjonować w Dobie Gospodarki 4.0 i Sieci 5G; Krajowa Izba Gospodarcza Elektroniki i Telekomunikacji, Fundacja Digital Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Potočan, V.; Mulej, M.; Nedelko, Z. Society 5.0: Balancing of Industry 4.0, economic advancement and social problems. Kybernetes 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, H. Modern Society has Reached Its Limits. Society 5.0 will Liberate Us, World Economic Forum. 11 January 2019. Available online: https://europeansting.com/2019/01/11/modern-society-has-reached-its-limits-society-5-0-will-liberate-us/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Nakanishi, H.; Kitano, H. Society 5.0, Co-Creating the Future. 2018. Available online: https://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2018/095.html (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Digital Global 2020: Global Digital Overview. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Digital 2020: Poland. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-poland?rq=Poland (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Digital 2019: Poland. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2019-poland] (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsóna, E.; Torresb, L.; Royob, S.; Flores, F. Local E-government 2.0: Social Media and Corporate Transparency in Municipalities. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Grębosz, M.; Siuda, D.; Szymański, G. Social Media Marketing; Politechniki Łódzkiej: Łódź, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aichner, T.; Jacob, F. Measuring the Degree of Corporate Social Media Use. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 57, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsóna, E.; Flores, F. Social Media and Corporate Dialogue: The Response of Global Financial Institutions. Online Inf. Rev. 2012, 35, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hysa, B.; Mularczyk, A.; Zdonek, I. Social media—the challenges and the future direction of the recruitment process in HRM area. Stud. Ekon. 2015, 234, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, E.C.; Mader, D.R.D.; Mader, F.H. Using social media during the hiring process: A comparison between recruiters and job seekers. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2019, 29, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R. Internet usage in the recruitment and selection of employees, Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology. In Organization and Management; Series No. 140; Silesian University of Technology Publishing House: Silesian, Poland, 2019; pp. 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoonen, W.; van Verhoeven, J.W.M.; Vliegenthart, R. Understanding the consequences of public social media use for work. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 33, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delerue, H.; Sicotte, H. Exploring the Use of Corporate Social Media by Project Team. In Proceedings of the 9th Multidisciplinary Academic Conference—MAC 2017, Prague, Czech Republic, 23 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harrin, E. Barriers to Social Media Adoption on Projects. In Strategic Integration of Social Media into Project Management Practice; Harrin, E., Ed.; PA IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 106–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bajracharya, J.R. Strength of Traditional and Social Media in Education: A Review of the Literature. IOSR J. Res. Method Educ. 2016, 6, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, A.; Hysa, B. Social media and Generation Y, Z—A challenge for employers, Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology. In Organization and Management; Silesian University of Technology Publishing House: Silesian, Poland, 2020; pp. 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojern, April 15, 2020. Social Media Accounted for 28% of Travel Marketers’ Digital Ad Spend in 2019—Could It Be Key to Your Hotel or Attraction during COVID-19? Available online: https://www.sojern.com/blog/facebook-and-instagram-for-hotels-and-attractions/ (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Destination Analysts 2019, The Future of Travel-Planning Apps. Available online: https://www.destinationanalysts.com/welcome-to-2019-american-traveler-sentiment-weakens-2-2/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Destination Analysts, Destination Inspiration. 2020. Available online: https://www.destinationanalysts.com/category/the-state-of-the-american-traveler/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Destination Analysts 2018, Is Influencer Marketing Worth Your Time? Available online: https://www.destinationanalysts.com/is-influencer-marketing-worth-your-time/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- WEX Raport 2019. U.S. Travel Trends. 2019. Available online: https://www.wexinc.com/insights/resources/u-s-travel-trends-2019-report/ (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Unwto, Global Guidelines to Restart Tourism. May 2020. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-05/UNWTO-Global-Guidelines-to-Restart-Tourism.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Szromek, A.R.; Hysa, B.; Karasek, A. The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fratričová, J.; Kirchmayer, Z. Barriers to work motivation of generation Z. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 2, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wiktorowicz, J. The situation of generations on the labour market in Poland. Econ. Environ. Stud. 2018, 18, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; RaiJyotsna Rai, Y. The Generation Z and their Social Media Usage: A Review and a Research Outline. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2017, 9, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicki, L. Boomers Have Big Travel Plans in 2020. In 2020 Travel Trends; AARP Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, P. Canada Digital Habits by Generation Identifying Key Distinctions across Age Groups, from Teens to Baby Boomers, Report. 5 February 2020. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/canada-digital-habits-by-generation (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Naidooa, P.; Ramseook-Munhurrunb, P.; Seebaluckc, N.V.; Janvierd Procedia, S. Investigating the Motivation of Baby Boomers for Adventure Tourism. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zabel, K.L.; Benjamin, B.J.; Biermeier-Hanson, B.B.; Baltes, B.B.; Early, B.J.; Shepard, A. Generational Differences in Work Ethic: Fact or Fiction? J. Bus. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 32, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupperschmidt, B.R. Multigeneration employees: Strategies for effective management. Health Care Manag. 2000, 19, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WEX Travel, Five Millennial Business Traveler Must-Haves. 12 December 2016. Available online: https://www.wexinc.com/insights/blog/wex-travel/5-millennial-business-traveler-must-haves/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Travel Marketing Across Generations in 2020: Reaching Gen Z, Gen X, Millennials, and Baby Boomers, Expedia Group Media Solutions. 11 December 2019. Available online: https://skift.com/2019/12/11/travel-marketing-across-generations-in-2020-reaching-gen-z-gen-x-millennials-and-baby-boomers/ (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Vukic, M.; Kuzmanovic, M.; Kostnic Stankovic, M. Understanding the Heterogeneity of Generation Y’s Preferences for Travelling: A Conjoint Analysis Approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Tourism Trends among Generation Y in Poland. Tourism 2012, 22, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, M.C.; Veiga, C.; Aguas, P. Tourism Services: Facing the Challenge of new Tourist Profiles. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2016, 8, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, A.; Fyall, A.; Byron, P. Generation Y: An Agenda for Future Visitor Attraction Research. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Nang Fong, L.H.; Law, R.; Luk, C. An Investigation of Gen-Y’s Online Hotel Information Search: The Case of Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Petrick James, F. Generation Y’s Travel Behaviours: A comparison with Baby Boomers and Generation X. Tour. Gener. Y 2010, 1, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Expedia Group Media Solutions. Generation, Z. A Look Ahead: How Younger Generations Are Shaping the Future of Travel, Custom Research. 2018. Available online: https://info.advertising.expedia.com/travel-and-tourism-trends-research-for-marketers?utm_source=skift&utm_medium=cpc&utm_content=2019-12-travel-and-tourism-trends-research-for-marketers&utm_campaign=2019-skift (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Bedyńska, S.; Ksiązek, M. Statystyczny Drogowskaz 3; Wydawnictwo Akademickie SEDNO: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, K.; Malik, M.Y.; Pitafi, A.H.; Kanwal, S.; Latif, Z. If You Travel, I Travel: Testing a Model of When and How Travel-Related Content Exposure on Facebook Triggers the Intention to Visit a Tourist Destination. Sage Open 2020, 10, 215824402092551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Correia, M.B.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. Instagram as a co-creation space for tourist destination image-building: Algarve and costa del sol case studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paül Agustí, D. Mapping tourist hot spots in African cities based on Instagram images. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Moscato, V.; Picariello, A.; Sperlì, G. Kira: A system for knowledge-based access to multimedia art collections. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 11th International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC), San Diego, CA, USA, 30 January–1 February 2017; pp. 338–343. [Google Scholar]

- IJspeert, R.; Hernandez-Maskivker, G. Active sport tourists: Millennials vs baby boomers. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2020, 6, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabaso, S.; Ade-Ibijola, A. Sell-Bot: An Intelligent Tool for Advertisement Synthesis on Social Media. In The Disruptive Fourth Industrial Revolution; Doorsamy, W., Paul, B., Marwala, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 674, pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Moscato, V.; Picariello, A.; Sperlì, G. An Emotional Recommender System for music. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł, K.; Maciuk, K. New heights of the highest peaks of Polish mountain ranges. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Moscato, V.; Picariello, A.; Sperlì, G. Recommendation in Social Media Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Third International Conference on Multimedia Big Data, Laguna Hills, CA, USA, 19–21 April 2017; pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Tkaczynski, A.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Truong, V.D. Influencing tourists’ pro-environmental behaviours: A social marketing application. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, S.N.R.; Mura, P.; Tavakoli, R. A postcolonial feminist analysis of official tourism representations of Sri Lanka on Instagram. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generations | [%] | Gender of Respondents [%] | [%] |

| Baby Boom (BB) | 2.00% | Female | 59.4% |

| X | 19.60% | Male | 40.6% |

| Y | 21.40% | ||

| Z | 57.00% | ||

| Level of education | [%] | Length of using SM | [%] |

| Basic/Junior high | 1.0% | Under 6 years | 78.84% |

| Secondary | 38.6% | From 4 to 6 years | 8.06% |

| Higher I | 27.5% | From 2 to 4 years | 2.52% |

| Higher II | 30.8% | Up to 2 years | 2.27% |

| Postgraduate | 1.0% | I don’t remember | 8.31% |

| PhD | 1.0% | Never used | 0% |

| BB | X | Y | Z | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Sd | Mean | Median | Sd | Mean | Median | Sd | Mean | Median | Sd | |

| Blogs and microblogs | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.56 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 1.29 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 1.59 |

| Social portals | 2.71 | 3.00 | 1.89 | 3.99 | 5.00 | 1.71 | 4.93 | 5.00 | 1.25 | 5.34 | 5.00 | 0.74 |

| Cooperation networks | 1.14 | 0.00 | 2.27 | 1.88 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2.10 | 2.00 | 1.48 | 2.47 | 3.00 | 1.34 |

| Content communities | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 3.16 | 3.00 | 1.52 | 3.94 | 4.00 | 1.43 | 4.78 | 5.00 | 1.17 |

| Rating portals | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 1.58 | 1.00 | 1.31 | 1.51 | 1.00 | 1.26 | 1.22 | 1.00 | 1.18 |

| Travel forums | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 1.22 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.18 |

| Types of Social Media | Generation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi Kwadrat | p-Value | Kruskal-Wallis | p-Value | |

| V1.1. Blogs and microblogs | 8.48 | 0.970 | 1.85 | 0.61 |

| V1.2. Social portals | 107.34 | <0.0001 | 62.49 | <0.00001 |

| V1.3. Cooperation networks | 87.47 | <0.0001 | 20.79 | 0.0001 |

| V1.4. Content communities | 180.67 | <0.0001 | 91.43 | <0.0001 |

| V1.5. Rating portals | 31.31 | 0.0018 | 15.04 | 0.018 |

| V1.6. Travel forums | 22.82 | 0.029 | 7.64 | 0.05 |

| Types of Social Media | V1.1 | V1.2 | V1.3 | V1.4 | V1.5 | V1.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1.1. Blogs and microblogs (e.g., Twitter) | 1.000 | 0.023 | 0.166 | 0.073 | 0.110 | 0.185 |

| V1.2. Social portals (e.g., Facebook, Google+) | 0.023 | 1.000 | 0.243 | 0.461 | 0.164 | 0.083 |

| V1.3. Cooperation networks (e.g., Wikipedia) | 0.166 | 0.243 | 1.000 | 0.270 | 0.155 | 0.105 |

| V1.4. Content communities (e.g., Youtube, Vimeo, Pinterest) | 0.073 | 0.461 | 0.270 | 1.000 | 0.120 | 0.035 |

| V1.5. Rating portals (e.g., TripAdvisor, Booking, HolidayCheck) | 0.110 | 0.164 | 0.155 | 0.120 | 1.000 | 0.514 |

| V1.6. Travel forums (e.g., Globetrotter, Fly4Free, Lonely Planet)) | 0.185 | 0.083 | 0.105 | 0.035 | 0.514 | 1.000 |

| Types od Social Media | V1.1 | V1.2 | V1.3 | V1.4 | V1.5 | V1.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1.1. Blogs and mikroblogs (e.g., Twitter) | 1.000 | 0.020 | 0.142 | 0.061 | 0.097 | 0.165 |

| V1.2. Social portals (e.g., Facebook, Google+) | 0.020 | 1.000 | 0.207 | 0.405 | 0.143 | 0.075 |

| V1.3. Cooperation networks (e.g Wikipedia) | 0.142 | 0.207 | 1.000 | 0.228 | 0.132 | 0.090 |

| V1.4. Content communities (e.g., Youtube, Vimeo, Pinterest) | 0.061 | 0.405 | 0.228 | 1.000 | 0.102 | 0.031 |

| V1.5. Rating portals (e.g., TripAdvisor, Booking, HolidayCheck) | 0.097 | 0.143 | 0.132 | 0.102 | 1.000 | 0.477 |

| V1.6. Travel forums (e.g., Globetrotter, Fly4Free, Lonely Planet) | 0.165 | 0.075 | 0.090 | 0.031 | 0.477 | 1.000 |

| Statement | Measure | BB | X | Y | Z | K–W Test | Man | Woman | M–W Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive opinions and comments in social media encourage me to go on holiday | Mean | 1.14 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.22 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 1.24 | 0.001 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Sd | 0.38 | 0.89 | 1.02 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.84 | |||

| In social media, I am looking for information about hindrances and problems that may arise in the places I intend to visit | Mean | 1.14 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.12 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 1.11 | 0.063 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Sd | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.82 | |||

| I use social media to learn about the history and culture of tourist places | Mean | 0.43 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.44 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.126 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Sd | 1.13 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.91 | |||

| Negative opinions and comments in social media make me resign from a holiday | Mean | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.016 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.429 |

| Med. | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Sd | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.99 | |||

| I use social media to plan a trip | Mean | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 0.000 |

| Med. | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Sd | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.93 | |||

| I use social media to establish relationships with the local community | Mean | −0.71 | −0.26 | −0.15 | −0.12 | 0.62 | −0.20 | −0.15 | 0.664 |

| Med. | −2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Sd | 1.60 | 1.23 | 1.33 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 1.26 | |||

| I check opinions/stories on places I want to visit on social media | Mean | 0.71 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.28 | 0.04 | 1.05 | 1.30 | 0.002 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Sd | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.79 | |||

| I use short term apartment rentals (e.g., Airbnb) | Mean | −1.57 | 0.21 | −0.11 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.17 | 0.087 |

| Med. | −2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Sd | 1.13 | 1.37 | 1.45 | 1.37 | 1.46 | 1.35 |

| Statement | Level of Significance of Differences between Generations or Gender | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZBB | ZX | ZY | YBB | YX | BBX | MW | |

| Negative opinions and comments in social media make me resign from a holiday | 0.079 | 0.119 | 0.006 | 0.434 | 0.361 | 0.241 | 0.429 |

| I check opinions/stories on places I want to visit on social media | 0.030 | 0.072 | 0.088 | 0.133 | 0.914 | 0.141 | 0.002 |

| I use short term apartment rentals (e.g., Airbnb) | 0.005 | 0.094 | 0.960 | 0.007 | 0.164 | 0.002 | 0.087 |

| Positive opinions and comments in social media encourage me to go on holiday | 0.415 | 0.013 | 0.033 | 0.974 | 0.784 | 0.819 | 0.001 |

| Hypothesis | Verification Result | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1.1 | There are statistically significant differences between the generations in the frequency of using different types of social media | Partially confirmed, no significant differences in terms of generation, only for blogs |

| Hypothesis 1.2 | Age moderates the strength of the relationship between the frequency of using different types of social media | Partially confirmed, interaction effect for cooperation networks and rating portals, as well as for content communities and social networks |

| Hypothesis 2.1 | Recommending a holiday with positive opinions and comments in SM is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Confirmed |

| Hypothesis 2.2 | Information searched for in SM regarding hindrances that may arise during travel is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 2.3 | Getting to know the history and culture of tourist places using SM is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 2.4 | Resigning from a holiday on the basis of negative opinions and comments in social media is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Partially confirmed, no significant differences in terms of generation |

| Hypothesis 2.5 | Planning a trip with the use of social media is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Partially confirmed, significant differences in terms of age |

| Hypothesis 2.6 | Establishing relationships with the local community through social media is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 2.7 | Checking opinions about tourist places in social media is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Confirmed |

| Hypothesis 2.8 | Opinion on the use of short-term apartment rentals is significantly different for individual generations and gender groups | Partially confirmed, no significant differences in terms of generation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hysa, B.; Karasek, A.; Zdonek, I. Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031018

Hysa B, Karasek A, Zdonek I. Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031018

Chicago/Turabian StyleHysa, Beata, Aneta Karasek, and Iwona Zdonek. 2021. "Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031018

APA StyleHysa, B., Karasek, A., & Zdonek, I. (2021). Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea. Sustainability, 13(3), 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031018