1. Introduction: Social Innovation and Art

A sustainable community is built upon different pillars, such as environmental, societal, and economic aspects. Having a viable industry basis to maintain livelihood, jobs, and income is one of them. However, as labor-intensive manufacturing shifts to low-waged developing countries and also tends to accumulate at several industrial clusters within countries, there is a serious hollowing out happening in many local communities in both developed and developing countries. While traditional policies and solutions aiming at regional economic growth by labor-intensive industrialization are losing their effects both in developed countries and a large number of localities in developing countries [

1], there is recently increasing anticipation for so-called “social innovation” to find a way to regenerate these communities by applying alternative methods.

Social innovation is a term used in various meanings, depending on the contexts and people it is being used by. Some may use it as an equivalent of an innovative social entrepreneurial endeavor, social enterprise, or a project, and others may refer to it as a systemic change to a society that can replace the traditional welfare state, governance mechanism, or industrial society. Still, the most commonly accepted understanding of social innovation is that it is an innovation that responds to a social issue or challenge or creates social value, and through its process, changes the value, behavior, rules, resources, and power allocation within a society, either in a small group of people, community, region, or whole country [

2,

3,

4]. By definition, it may not necessarily be a beneficial or “good” thing for all stakeholders, nor is it value-neutral, but it is generally considered an initiative to bring (at least a net) positive change to the society through empowerment and inclusion of marginalized groups, socio-economic vitalization, or sustainable or just practices [

5].

Recently there is growing literature on the impact of social innovation at regional or community levels, and how successful initiatives are processed. This group of literature shed light on different roles and contributions from various stakeholders in local ‘ecosystems,’ the importance of community engagement, and the crucial role of systemic innovators (or ‘institutional entrepreneur’) to lead the process to generate, implement and diffuse successful projects coming from various backgrounds, such as ‘entrepreneurial philanthropy,’ public or corporate sectors, or civil society [

6,

7,

8].

Although social innovation enjoys rich input from art-related ideas and methodologies such as creativity and design thinking, and also there is affluent literature investigating the connection between art and community such as community-based art [

9,

10,

11,

12], art itself is one of the under-treated topics in the social innovation field of academia. Nonetheless, art, including contemporary art, is a quickly growing market in industrialized societies and emerging economies such as China. It also has the potential to replace declining manufacturing industries as one of the ‘creative industries,’ to contribute as an engine to generate economic and social values (such as employment and personal exchange) in both urban and rural communities [

13]. Still, art in social innovation literature is mostly treated in the context of territorial development, mainly as a tool to stimulate participation and to connect stakeholders from diverse backgrounds in local communities [

14,

15,

16,

17].

However, some authors, including Tremblay and Pilati [

18], by applying the concept of ‘cultural district’ and presenting the case of Cirque du Soleil in Montreal, argue that culture–creative territorial actors of urban areas have the potential to help social development by reinforcing local identity and integrating marginalized groups as well as economic revitalization in a post-industrial economy. Additionally, Lin and Chen [

19], by using their own term of ‘societal innovation,’ illustrate how four UNESCO-nominated Creative Cities (Kanazawa, Lyon, Ostersund, and Norwich) developed large-scale systemic and structural changes at the city level. The initial ‘innovators’ initiate the project by utilizing local resources, then scale it by receiving support from enabling policy environment of motivated partners.

Cancellieri et al. [

20] also present the culture-led regeneration projects of declining urban communities in Europe as a means to produce social cohesion, beyond the economic impact and improvement of residents’ quality of life brought by external investments. They define social cohesion as the ongoing process of developing a community of shared values and trust, with dimensions of belonging, inclusion, and participation. In cases from Italy (Milan), France (Paris), and Spain (Lugo), a policy opportunity was created by a city or municipal government with support from the central government, EU programs, grant-making foundations among others. This allowed civil society organizations and social enterprises to take the lead and form different patterns of partnerships between local public administration, private for-profit organizations, artists, and local communities including vulnerable groups, such as immigrants and people with disabilities. In each case, the local multi-stakeholder network enables the design, implementation, and encourages local participation in cultural projects aimed at social cohesion by utilizing abandoned public spaces such as buildings, local markets, and bus stops.

Another stream of literature argues that art exhibitions and art tourism, including Biennales and Triennales, had positive impacts on tourism, economics, and environmental conservation, as well as creating physical and emotional interaction between the audience and communities, by taking the examples of One Malaysia Contemporary Art Tourism and Kuala Lumpur Biennale, contemporary art practice in the Philippines, and Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in Japan [

21,

22,

23]. Franklin also investigates how the cultural tourism at Bilbao, Spain was developed by the external resource (Guggenheim Museum Bilbao) and local stakeholders (Bilbao and Basque Country region) [

24]. In general, they present the promising potential of art tourism as the tool for local regeneration in both developed (post-industrial) and developing country contexts.

Still, as Tremblay and Pilati [

18] (p. 71) point out, this “emphasis on the culture- or creativity-based policies for local development is not yet supported by sufficient case studies”. The literature mostly lacks—apart from Cancellieri et al.—which describe the different patterns of cross-sector partnerships leading the cases [

20], in-depth analysis of how different sectors such as local governments, businesses, and civil societies have contributed to, and have been impacted by the initiatives. Moreover, the greater part of the existing studies is based on analyses of urban areas in European or Anglosphere countries, not much from rural areas and/or non-European countries, including Asia.

2. Aim of the Research and Methodology

Although urban regeneration by art continues to be a major concern in many of the developed societies as well as in many of the developing and emerging economies, there lies another unanswered question of whether art as a social innovation may be utilized to revive rural and deserted communities in aging societies, and if it is possible, how could it be done. In this paper we propose a model from the case of Benesse Art Site Naoshima (BASN) and Art Setouchi (which includes the Setouchi International Art Festival held every three years (hereunder Setouchi Triennale)—for the time being, 2010; 2013; 2016; and 2019—and related continuous activities held in the region) operated in the islands of Seto Inland Sea in Western Japan.

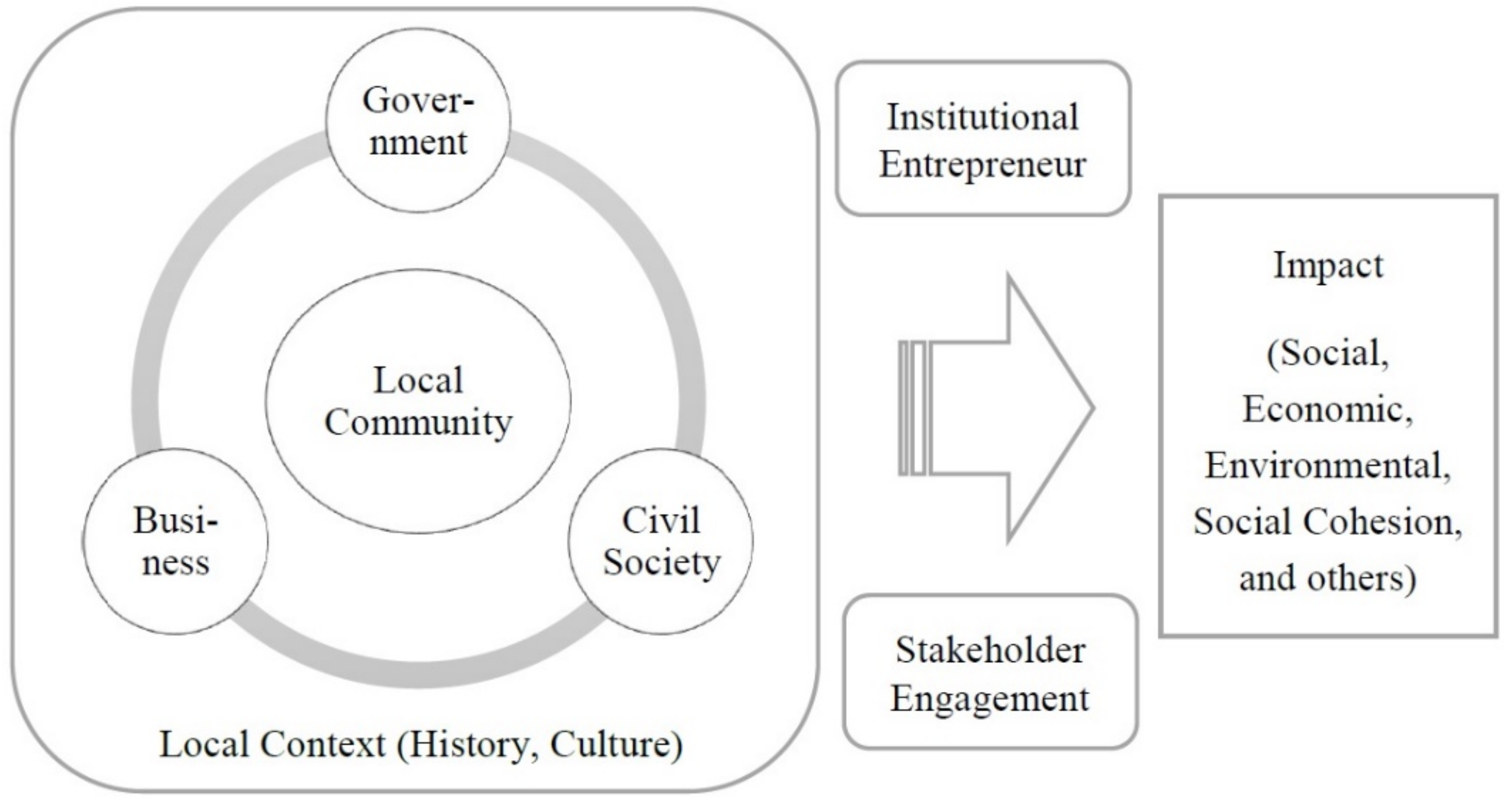

This study adopts the following framework to analyze the process of social innovation. The framework has four key components: (1) the role of three sectors (government, business, and civil society including philanthropy) and inter-sectoral cooperation, framed in the local historic, cultural, relational, and power contexts; (2) the significance of ‘institutional entrepreneur’ such as (but not restricted to) ‘entrepreneurial philanthropy’ to scale the social innovation initiative and to involve local stakeholders, and (3) engagement of local stakeholders to the initiative; and (4) the impact and change caused to the local community (

Figure 1) [

8,

25].

There is already a considerable body of literature on BASN and Art Setouchi/Setouchi Triennale, including documentation written by key persons involved in the processes, which mostly focuses on the contribution of local governments (Naoshima town and Kagawa prefecture) and private business (Benesse Holdings) to develop the initiatives [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

This study is based on the review of existing literature and archival analysis together with supplementary fieldwork and in-depth semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders. Interviews took place from July 2020 to July 2021 to hear mainly about their personal experience in BASN/Art Setouchi activities. Interviewees included Mr. Soichiro Fukutake and Mr. Fram Kitagawa, and others—three from public (Naoshima town office and local council), six from private (Benesse Holdings and relevant corporates, and local businesses), and four from civil society sectors (Fukutake Foundation and other nonprofits and local residents). Based on the collected information, we apply a tri-sectoral analysis framework [

20,

35] to reconstruct the development of BASN/Art Setouchi as social innovation processes, then to review the contribution from three different sectors (government, private, and civil society). We also examine whether BASN/Art Setouchi as social innovation had an economic effect and improved the well-being of the community, and provided social cohesion alongside the value and perception of the society. The study received approval (number: Soc_2021_03) from the Research Ethics Committee, Graduate School of Humanity and Social Sciences, Okayama University.

Following this,

Section 3 describes the processes and stages of BASN and Art Setouchi, then

Section 4 focuses on the role of two personalities, Soichiro Fukutake and Fram Kitagawa in the process before

Section 5 summarizes the findings.

3. Process and Stages of BASN and Art Setouchi

3.1. Seto Inland Sea: Benesse Art Site Naoshima and Art Setouchi

Benesse Art Site Naoshima and Art Setouchi lie in the Seto Inland Sea, which is one of the first national parks in Japan since 1934 and is praised for the beauty of its island areas (

Figure 2). However, certain islands (Naoshima and Inujima) were also used as copper refinery sites in the modern era causing serious damage to the local natural environment. Facilities to isolate the patients of Hansen’s disease were also built-in islands, including Ohshima and Nagashima. In Teshima, since the 1970s, a private company unlawfully disposed over 900 thousand tons of industrial waste, and the prefectural government finally agreed to remove all wastes and recover landscapes only after decades of local protests and lawsuits. Moreover, these areas which once enjoyed the privileges and wealth by being a hub of transport and logistics in pre-modern Japan, have now lost that standing and suffer from severe depopulation and aging. For example, in Naoshima the population fell from 7501 in 1955 to 3325 in 2010, with 30.4% of its population over 65 years old [

36].

3.2. Stage Zero (1985–1992): A Campsite

Chikatsugu Miyake, who served for 36 years (1959–1995) as the mayor of Naoshima town, sought to develop another industry in Naoshima, which at the time, heavily depended on the refinery established by Mitsubishi Material. First, they invited Fujita Kanko, a tourism developer to acquire land in the southern part of Naoshima and develop a beach resort. The facility opened in 1967 but suffered from slow business and practically withdrew by 1976.

Then Tetsuhiko Fukutake, the President of Fukutake Publishing (now Benesse Corporation), an education company based in Okayama city, met Mayor Miyake in 1985 and agreed to re-develop the site as an international camping site for children. Tetsuhiko passed away in 1986, but his son and successor Soichiro Fukutake bought the land of 165 hectares (approximately one-sixth of the island) and built the Naoshima International Campsite in 1989, designed by architect Tadao Ando. At the same time, the Naoshima town developed an objective, which they named “Naoshima Cultural Village” in 1988 with a goal to re-develop and revitalize the island’s southern area as a cultural zone.

3.3. Stage One (1992–1997): A Museum

It was Soichiro Fukutake’s vision to introduce contemporary art to Naoshima, moving beyond what his father planned [

27] (p. 18). It started in 1992 as an ultramodern museum-hotel (Benesse House), again designed by Tadao Ando [

26] (p. 106). It was located in the southern part of Naoshima previously bought by Fukutake Publishing, isolated from residential areas in the eastern and western parts of the island. In the beginning, the Benesse House was the only location used to host art exhibitions. The “Out of Bounds” exhibition hosted in 1994 was the first exhibition that utilized Naoshima’s rich nature and placed pieces amongst it, including the iconic “Yellow Pumpkin” artwork by Yayoi Kusama. This led to a stronger push towards ‘site-specific art,’ where artists would visit Naoshima to produce their work on-site instead of having their finished piece be purchased.

In 1995, Fukutake Publishing changed their company name to “Benesse.” taken from the Latin “well-being”. The same year it also become a listed company, with the Fukutake family donating a large amount of their stock to set up a foundation to support the initiative (Naoshima Fukutake Art Museum Foundation). Since then, BASN became a joint project between Benesse Holdings, a for-profit business, and the foundation (renamed as Fukutake Foundation since 2012), a philanthropic organization.

3.4. Stage Two: Art in Community

The turning point for BASN arose when BASN was asked by the town to acquire an old house in the Honmura area, one of the residential areas in Naoshima [

31]. BASN renovated the house and installed a piece of artwork—of over 100 LED digital counters placed in water (“Sea of Time ‘98” by Tatsuo Miyajima)—as a part of the house. This house (Kadoya) became the first of the 13 (by September 2021) “Art House Project” series, which utilize old unused houses and buildings (including a local shrine, Go-o shrine) in local community as an art site. Moreover, in 2001, the “Standard” exhibition was held in three areas of Naoshima (Honmura and Miyanoura residential areas and the Mitsubishi Material area), where artists fused the deserted houses and their original art pieces. Through the Art House Project, BASN expanded their reach from the southern area to all of Naoshima, and local residents little by little started to participate either as a co-creator of artworks (for example, 125 Naoshima residents set the speed of LED digital counters used for the “Sea of Time ‘98“) or as volunteers and guides for the art exhibitions [

32].

At this period, BASN also expanded to two neighboring islands, Inujima and Teshima. This led to the creation of two museums, the Inujima Seirensho Art Museum, which utilized the abandoned copper refinery, and the Teshima Museum, which opened in 2008 and 2010, respectively, followed by Art House Projects and other art sites in the islands.

3.5. Stage Three: Art Alongside the Community

Following the areal expansion of BASN and the plan to organize an art festival across islands both from BASN and the Kagawa prefecture, the first Setouchi Triennale was held in 2010. Seven islands including three BASN islands and Takamatsu port participated, and 75 artists from 18 countries and areas contributed. The event counted 930,000 visitors in a 105 days period, which was about three times over the prior estimate [

37]. Having the Governor of Kagawa prefecture as the Chair, Soichiro Fukutake as General Producer, Fram Kitagawa as General Director, the Setouchi Triennale continued throughout 2013, 2016, and 2019, attracting art-lovers not only from Japan but also from other countries. 2019 Triennale received 230 artists from 32 countries and areas, 1.17 million visitors in 12 islands and Takamatu & Uno port areas [

38].

In Setouchi Triennale, Kitagawa encouraged artists to hold the process of co-creation with local islanders, and there were some artworks highlighting the history of islands, such as the most striking works in Ohshima in the 2019 Triennale. The artist Keizo Tashima created an art space using a room, a wooden toilet pot, and writing based on what he heard from Mr. N, a patient of Hansen’s disease who was forced to stay in the sanatorium by the government.

Partly because of the need for accommodation, food, and drinks for the visitors, local residents as well as newcomers started food and accommodation businesses, mainly in Naoshima but also in other islands. The additional dimension of local food and traditional culture in Art Setouchi allows the festival itself to expand beyond art and become something more holistic. Villagers also had chances to interact with artists and visitors to co-create and guide the artworks in the community, through providing food and drinks for them. A volunteer group named “

Koebi-tai (small shrimp group)” was also founded in 2009 to support the creation of the artworks, reception, and other managerial tasks of Art Setouchi and Setouchi Triennale. There were over 9400 cumulative person/day

Koebi-tai volunteers for the 2019 Setouchi Triennale, with around 18% volunteers coming from overseas, mainly from Asia [

38].

3.6. Summary

After more than 30 years of efforts from BASN and Art Setouchi, we can say for certain that the art sites and the movements have been a case of social innovation in these Setouchi islands. Especially regarding the economic and infrastructural impacts, the islands have now become a place to attract hundreds of thousands of international art lovers every year through their art, architecture, and nature, although the stream had to be largely stopped due to the COVID-19 pandemic since 2020. The Bank of Japan Takamatsu branch estimates the economic effect of the 2019 Setouchi Triennale as 18 billion yen (approximately USD 160 million) [

39]. Thanks to the visitors, infrastructure such as ferryboats have been upgraded and maintained, and new local businesses are emerging. According to the government Economic Census, the number of private businesses in the accommodation industry in Naoshima increased from 14 to 31 between the years 2009 and 2014 [

40]. Moreover, there are settlers migrating to the islands, and on one island, a once closed elementary school was re-opened because of the newcomers [

30]. In Naoshima, the incoming population exceeded the outflow in the years 2015, 2016, 2018, and 2019. Moreover, most of the incoming people are in their twenties [

41].

As Nonaka et al. [

33] acknowledge, the focus on contemporary art as the “best practice” of rural regeneration definitely helped the islands attract a specific audience and change a stigma once given to the area to a more positive image. One of the local residents in Naoshima rephrases this: “Naoshima only had negatives twenty-five years ago. Now all of them are turning out to be positives”.

For social cohesion, there is a number of anecdotal evidence such as the elderly citizen embracing the interaction with artists and visitors, but the whole picture is not clear yet. According to the 2019 Setouchi Triennale Report, while 73.4% of respondents acknowledge that the Triennale contributed to the revitalization of the local community, the majority of them responded that they had no (or little) interaction with artists and/or visitors (57.4%) and that they were not involved in the Triennale-related activities (66.2%). 62.9% stated that they want the next Triennale to be held on their own island, but 22.2% stated they are either unsure or opposed to the next Triennale [

38].

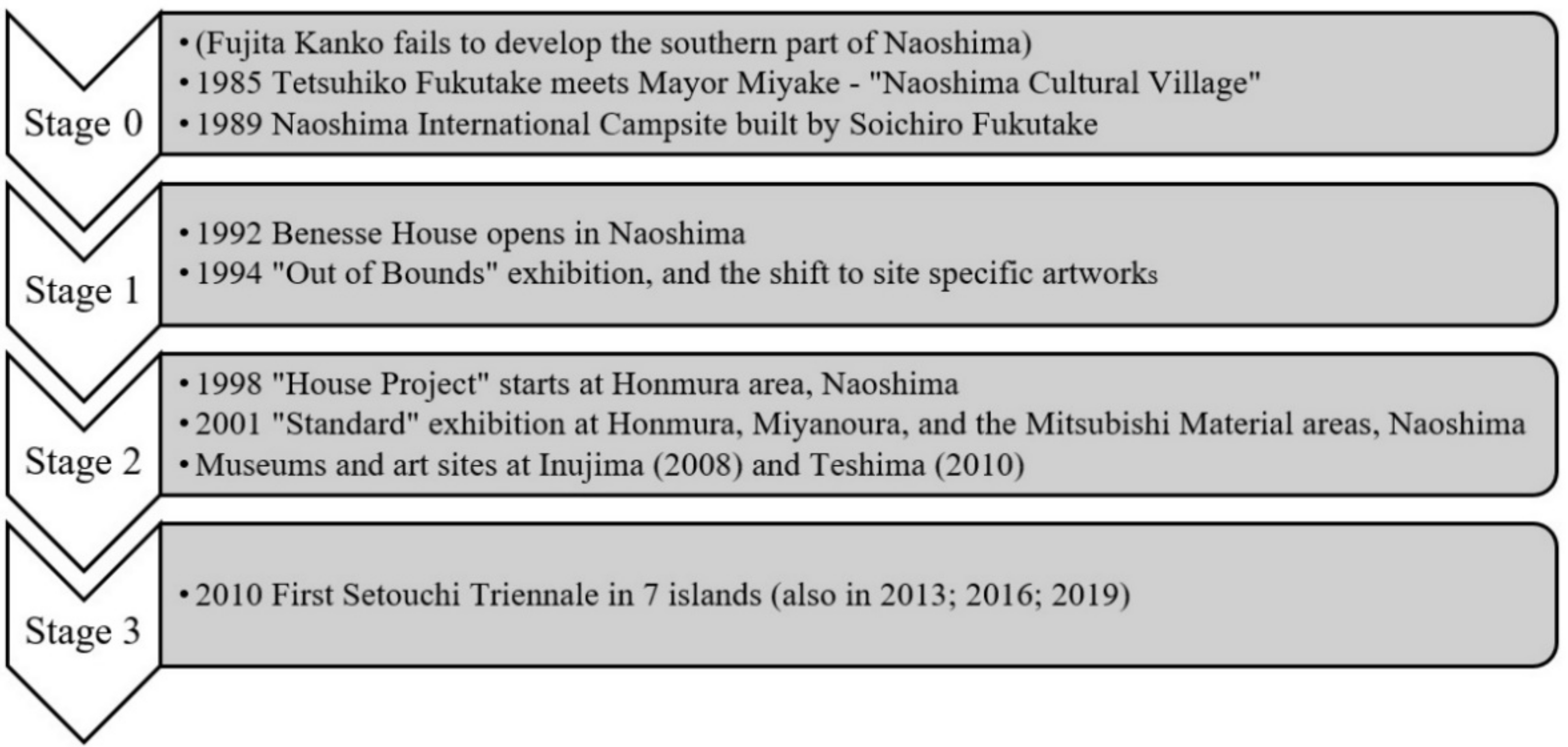

Figure 3 summarizes the processes and stages of BASN and Art Setouchi (the format of the figure is partly modified from Cancellieri et al. [

20]). It can be seen as a steady development from a campsite (stage 0)/corporate-owned museum/hotel (stage 1) that expanded to the residential communities first in Naoshima then next to Inujima and Teshima (stage 2), and finally flourished as the Setouchi Triennale held together with local residents and volunteers (stage 3). In parallel, the engagement of local residents with art sites increased, as the methodology shifted from ‘camp site’ (stage 0), ‘art museum’ (stage 1) to ‘art in community’: art installed in the local community (stage 2), and finally to ‘art alongside the community’: art projects created together with local people and/or based on local history and memory (stage 3).

However, one notable fact about this process is that it was not planned from the beginning with a clear blueprint or roadmap, but was rather developed through the various problem appearing and through seeking the involvement of various individuals who could solve those direct problems. Some of them were Benesse employees (like Akimoto and Kasahara), some were from the Naoshima town (former mayor Miyake) or Kagawa prefecture governments (former governor Manabe), with many others coming from civil society or local community backgrounds.

5. Conclusions

The main theoretical findings of this paper are threefold. First, this study adds to the literature on social innovation which recognizes its implication and meaning at the local community level in general, and more specifically those on utilizing cultural and artistic projects as its vehicle to develop community regeneration by both economic development and cultural cohesion.

Second, we emphasize the role of the civil society sector in this initiative which was largely overlooked in the previous literature, including the role of Fukutake as the ‘institutional entrepreneur’ and ‘entrepreneurial philanthropy’ to give the vision and momentum to the project and orchestrate different stakeholders, and also Kitagawa’s contribution to bring in core ideology and methodology to Art Setouchi.

Third is how art, especially contemporary art served as the vehicle of social innovation, not only to bring in outsiders but also to create personal relationships and social cohesion. This seems to be surprising and even counterintuitive. Since contemporary art is something not easily consumable and understandable (for instance, like scenery and food), it can be a process to create the linkage—or ‘dialogue’ as Kester describes [

10]—between the tourists from outside and local residents who help as a guide and ‘interpreter’ to explain the art and its process, as well as their own livelihood, history, and culture that the art is based on. Both Fukutake and Kitagawa were intentional about the catalytic effect of art in their methodologies, and also encouraged the art projects to reflect the voice of people and place, and to co-create with local residents, as the BASN/Art Setouchi process developed [

29,

31,

45]. Moreover, the initiative also expanded its scope as it gradually enjoyed having a higher level of local community engagement in art projects, which was also heightened by Kitagawa.

We may not say that the BASN and Art Setouchi is a fully scaled social innovation at the moment, but we can surely say that they are showing a promising prototype of social innovation, successfully utilizing art for the revival of rural communities and the engagement of local residents and outsiders. We can say so first by viewing the actual change it caused on the area, both the socio-economic impact and the improved islanders’ values and mindsets. Second, it is visible in the disruption BASN and Art Setouchi caused towards the way art is created, installed, and experienced, which is a departure from the traditional ‘white box’ art museums and art pieces. The new model is being replicated in different parts of Japan, and other places in Asia including China [

28].

Still, the concrete evidence of how it helped social cohesion and well-being of local residents is not existent, which is the limitation of this study. Another limitation is that due to the scope of this paper and the lack of expertise of the author, this study cannot make any substantial judgment on the artistic or aesthetical quality of art projects.

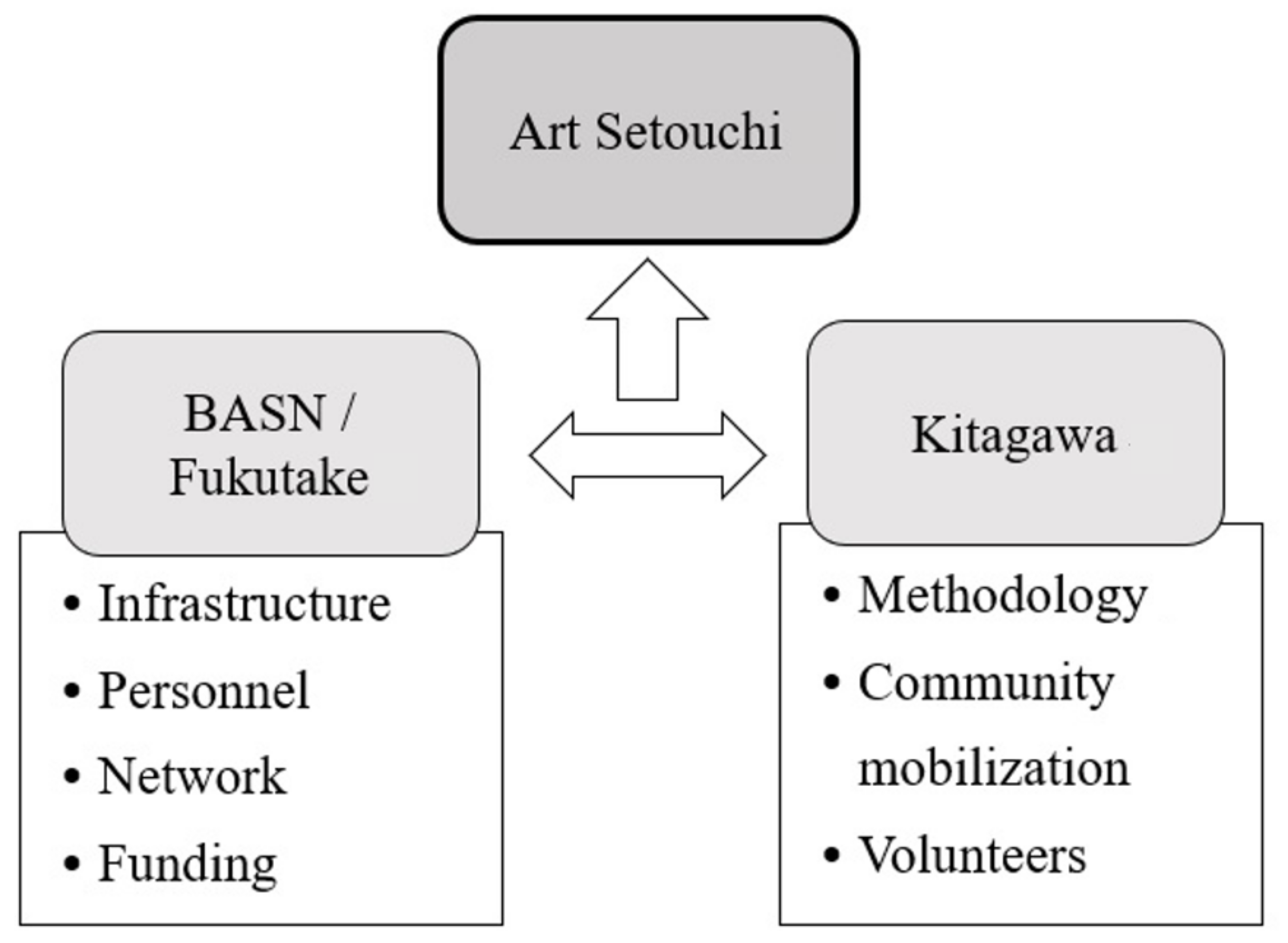

Among the number of key figures and talents involved in the processes coming from all three sectors (government, business, and civil society; including former mayor Miyake, former governor Manabe, architects Tadao Ando and Hiroshi Sanbuichi, and others from the Benesse/Fukutake Foundation, including Yuji Akimoto, who served as the curator of BASN until 2006), we focused on two characters, Soichiro Fukutake, and Fram Kitagawa. They have contrasting backgrounds, one from business and the other from art and social movement, and their values seem to be quite different. Still, two of them work in tandem as the producer and director of both the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale and the Setouchi Triennale. Fukutake, as the ‘entrepreneurial philanthropist’, together with Benesse built the ‘crown jewel’ art sites in Naoshima and other Art Setouchi islands through BASN, as well as mobilizing people, resources, and infrastructure needed. He also kept the momentum of the ‘why’ by keeping a focus on the constructed visions and values. Kitagawa, by his tireless negotiation and organization, gives life to the whole process by breaking the balance and bringing diversity and energy, which separates Art Setouchi from other government-organized art festivals. Without even one of them, BASN/Art Setouchi could not be a social innovation, at least not at the scale it is today. We summarize this as

Figure 4, as a ‘dialectic’ of two initiatives together creating Art Setouchi by bringing in different resources and methodologies:

As a tri-sectoral analysis of social innovation, we argue that the crucial values and methodologies of BASN and Art Setouchi (especially the latter) were brought from the civil society sector. The value of both Fukutake and Kitagawa cannot be explained solely by the motivation and logic of government or business sectors. This has been largely overlooked in the existing literature which focused more on the business (Benesse) and/or governments as the driver of change [

32,

33,

46], but it is crucial to understand the nature of these initiatives.

Of course, this has nothing to undervalue the contribution from public or private business sectors. Without the Naoshima town creating the space (both metaphorically and practically) and supporting the initiatives by policy incentives and coordinating public infrastructure, Naoshima could not be the ‘island of art’. Additionally, without human resources and investments put in from Benesse, which is the backbone of the initiative, this could not be sustained for over thirty years to see its success.

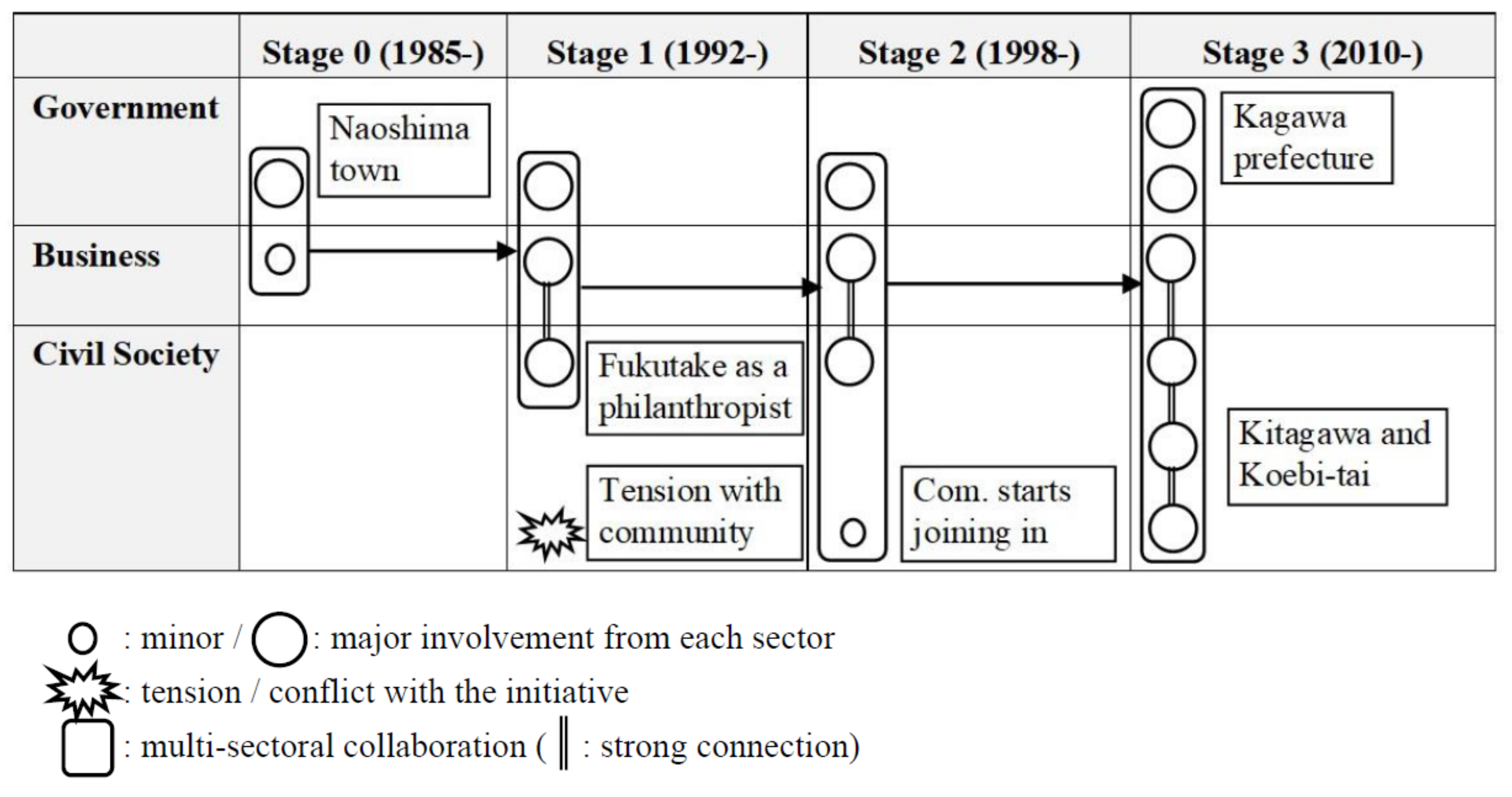

The contribution of the three sectors is summarized in

Figure 5. In stage zero, Naoshima town takes the lead to invite external businesses to develop a tourist site (first Fujita Kanko then Fukutake Publishing), and Tetsuhiko Fukutake responds with the idea of building a campsite. Then, at stage one, Soichiro Fukutake brings in his own vision to revitalize Naoshima by using contemporary art as a medium, both in his capacity as a business leader and philanthropist, but at this stage, the activities are mostly limited in the Benesse House area and there is some tension with local communities for them to come into their residential areas. However, by stage two, the art projects and exhibitions are expanded to residential areas and communities start to collaborate with the initiative. Finally, at stage three, with the help of ideas and methodologies brought by Kitagawa including the volunteer group Koebi-tai, island communities are mobilized in full scale and participate in the Setouchi Triennale and related events. With the support from the new-coming Kagawa prefectural government, it seems like an example of fortunate collaboration of all three sectors, but we can also see that it was not that balanced in the beginning, and the “hub” of the collaboration are the two figures, Fukutake and Kitagawa.

This leads us to another issue of applying this model to other countries and areas, and the practical contribution of this study to advice on the application. Fukutake advises others not to follow Naoshima as a model, but to apply its principle to meet the needs of local residents [

28] (p. 4). We echo his suggestion, especially if what they want to replicate is Art Setouchi, rather than BASN. It requires not only a heavy investment in art products and infrastructure, but also a person who can (1) envision, and advocate for the initiative, (2) bring in necessary people and resources such as artists, patrons, and infrastructure, and win their support, and (3) connect the sense of local participation and ownership by connecting art with local history, memory, and community engagement. But such talent is scarce. Even in BASN/Art Setouchi, Fukutake and Kitagawa needed to divide the roles. However, if the value of such personnel and processes can be appreciated, it may avoid replicating spiritless art museums and festivals in rural communities by government policy or business or philanthropic wealth.

This also leaves the question of what BASN/Art Setouchi will look like without the two titans, Fukutake and Kitagawa. Both key persons connected different sectors and fields and allowed both BASN and Art Setouchi become what it is today. With their departure someday, it is hard to tell if there will be a need for them to pass their mantel to a new figure, or if the system they created will be able to sustain itself regardless of their presence.

Moreover, even for Art Setouchi, apart from the major challenges caused by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, there is a serious concern left. Although the local community engagement seems to be established, the issues of local ownership and voice representation are still left as an unanswered question. In spite of its significant success, the population trend in Naoshima continues to decrease: the flow of incoming newcomers is not yet enough to cover the losses caused by the death of elderly islanders. Some of the islands like Inujima are becoming virtually deserted. Now in Teshima, there is an artwork called “Les Archives du Cœur”, by late Christian Boltanski, which collects people’s heartbeats, memorizing them even when they are gone. If this trend continues, finally what there may be left could be artworks and art sites welcoming visitors, run only by outsider staff—can we call that the art reviving communities, or art memorizing them?