Does COVID-19 Change CSR? A Family Business Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

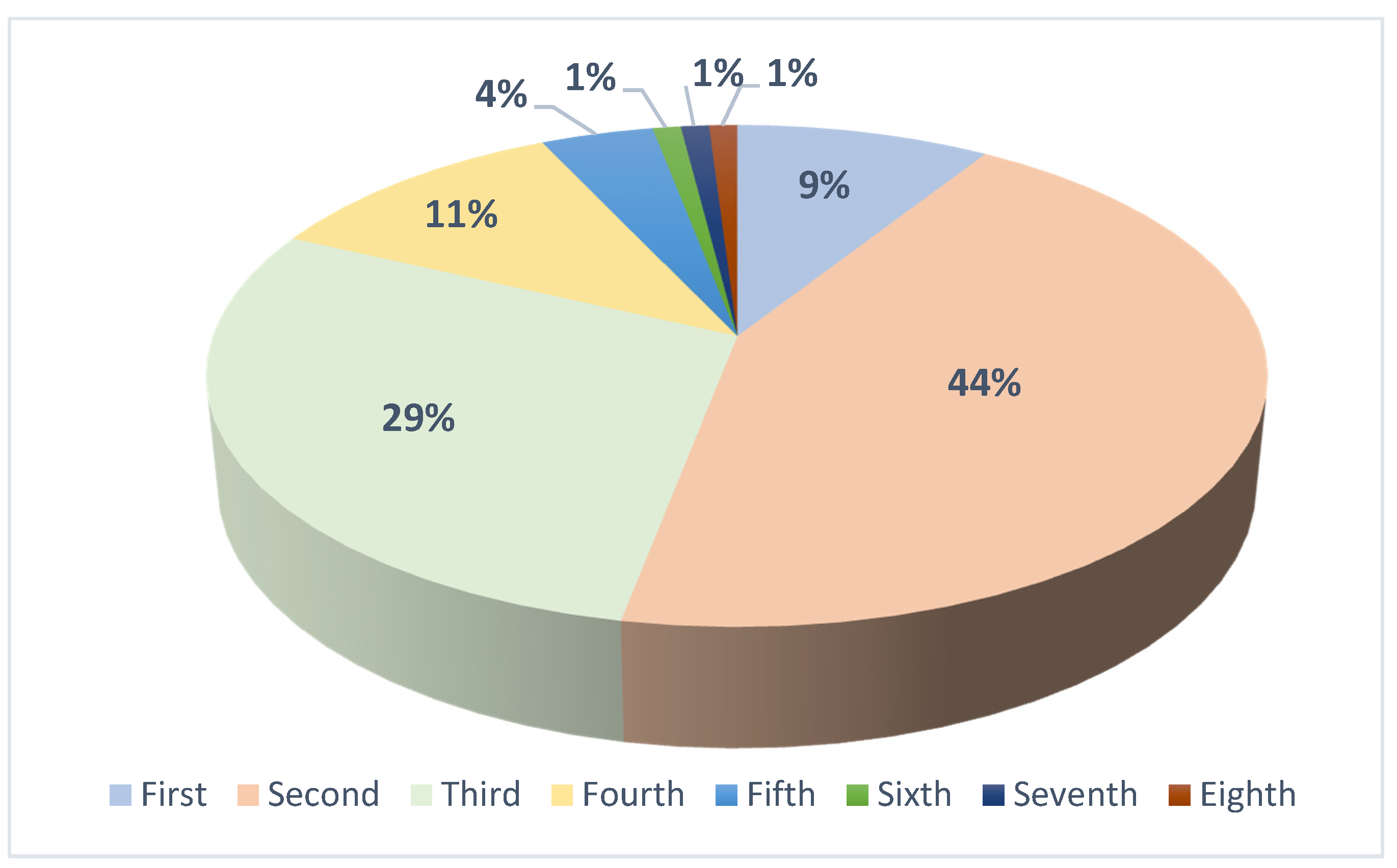

3.1. Generation

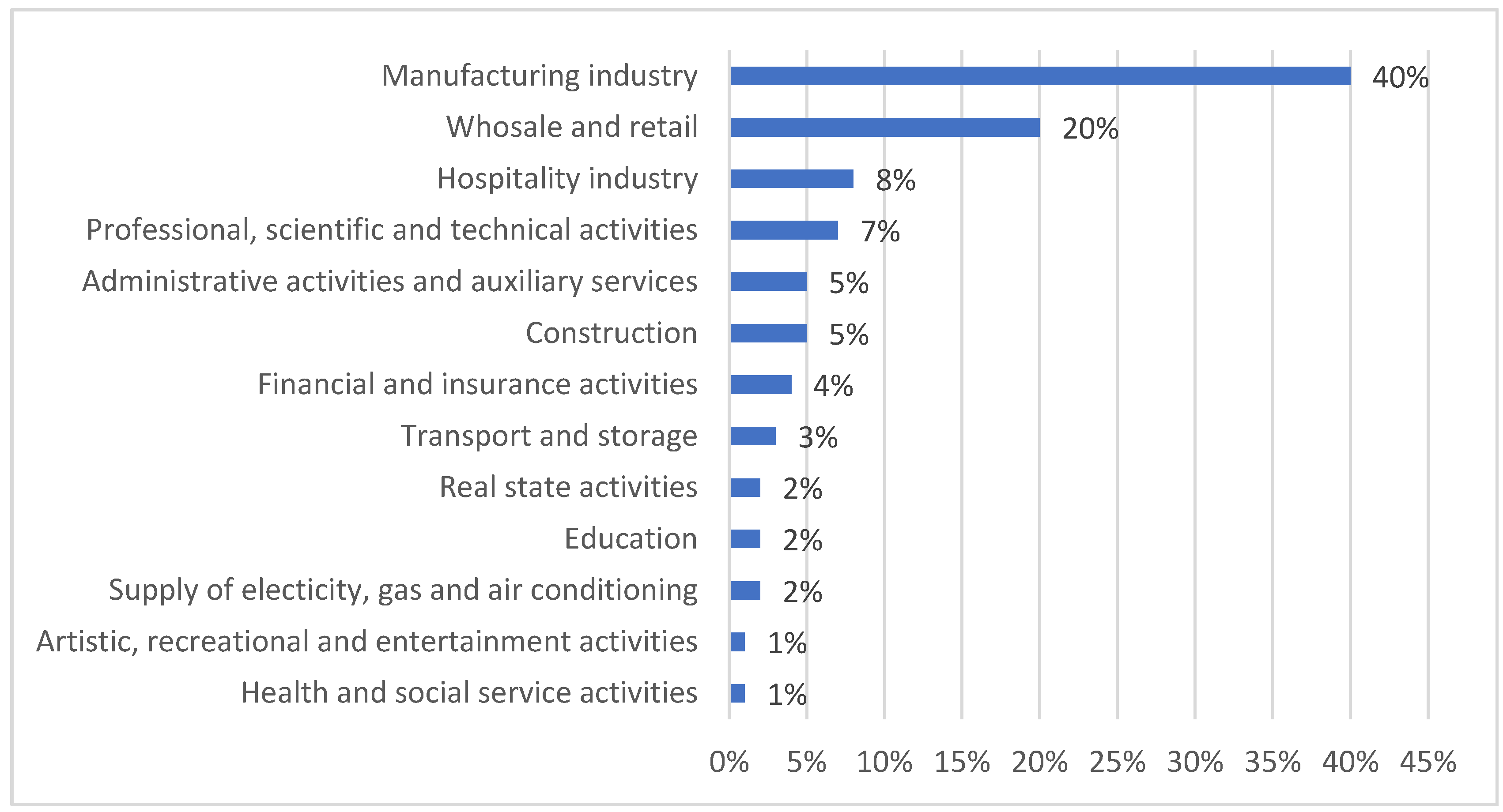

3.2. Business Sector

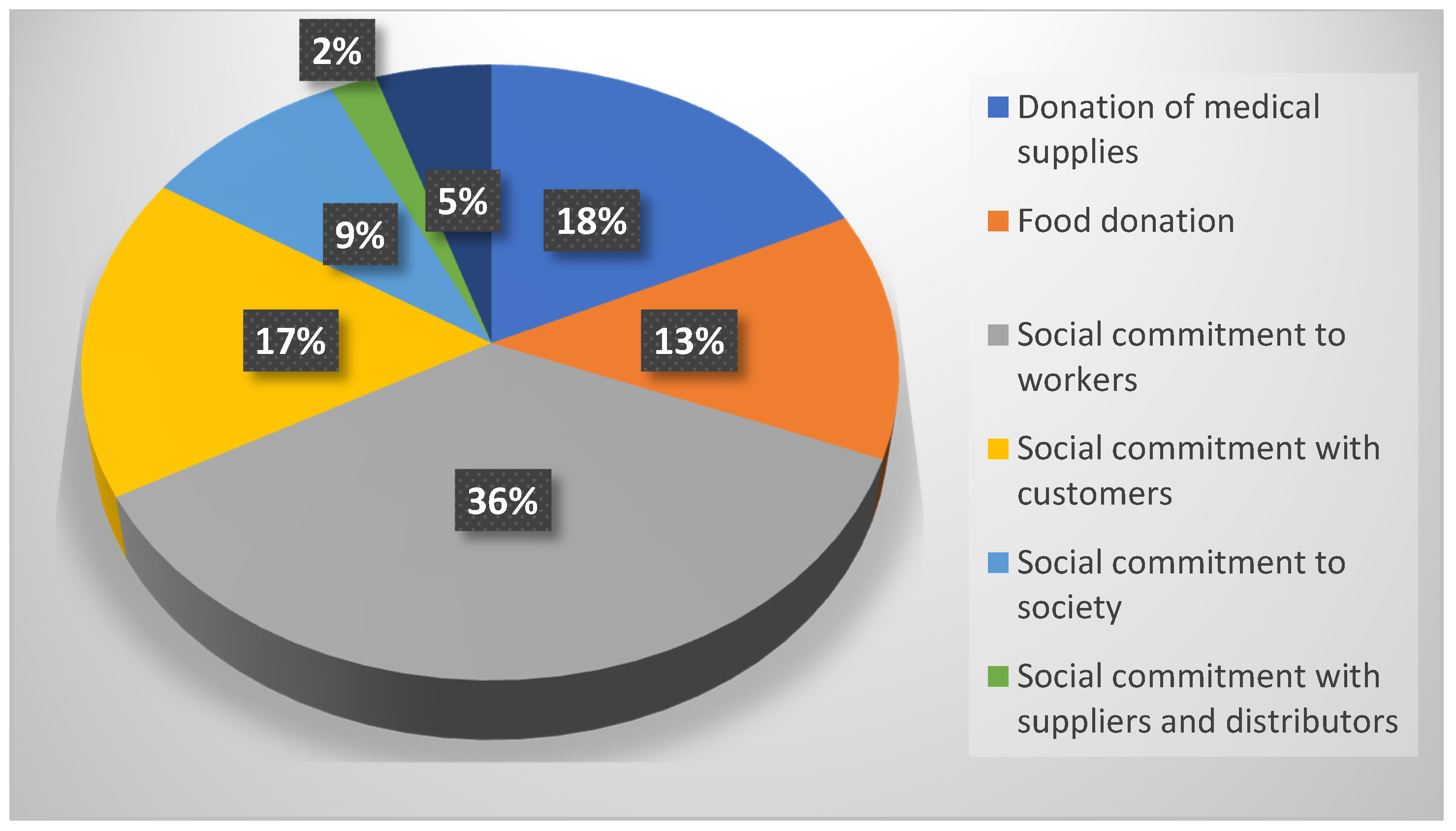

3.3. CSR Activities

4. Conclusions

- Theoretical and Practical Implications

- Limitations and Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fonseca, A.P.; Carnicelli, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability in a Hospitality Family Business. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; Sharma, P. Defining the family business by behaviour. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Final Report of the Expert Group–Overview of Family-Business; Relevant Issues: Research. Networks, Policy Measures and Existing Studies; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Curado, C.; Mota, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Sustainability in Family Firms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Shanker, M.C. Family businesses’ contribution to the U.S. economy: A closer look. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivo-López, E.; Villanueva-Villar, M.; Michinel-Álvarez, M.; Reyes-Santías, F. Corporate social responsibility and family business in the time of COVID-19: Changing strategy? Sustainability 2021, 13, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de la Empresa Familiar. Available online: https://www.iefamiliar.com/asociaciones-territoriales/ (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- IMF. Annual Repport. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/2020/eng/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Torres, R.; Fernández, M.J. Se inicia la recuperación, pero persisten las incertidumbres. Cuad. Inf. Econ. 2020, 277, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Astrachan, C.B.; Botero, I.; Astrachan, J.H.; Prügl, R. Branding the family firm: A review, integrative framework proposal, and research agenda. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2018, 9, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, C.A.; Ferguson, K.E.; Pieper, T.M.; Astrachan, J.H. Family business goals, corporate citizenship behaviour and firm performance: Disentangling the connections. Int. J. Manag. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 16, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivo-López, E.; Villanueva-Villar, M.; Vaquero-García, A.; Lago-Peñas, S. Do family firms contribute to job stability? Evidence from the great recession. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D. Family firms and practices of sustainability: A contingency view. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Employment. Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Buchholtz, A.K. Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability, and Stakeholder Management; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique, A.M. La Planificación de la Comunicación Empresarial; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; Volume 202. [Google Scholar]

- Mata, P.; Buil, T.; Gómez-Campillo, M. COVID-19 and the reorientation of communication towards CSR. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Truant, E.; Zicari, A. Internal corporate sustainability drivers: What evidence from family firms? A literature review and research agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erjavec, K.; Janžekovič, M.; Kovač, M.; Simčič, M.; Mergeduš, A.; Terčič, D.; Klopčič, M. Changes in Use of Communication Channels by Livestock Farmers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cara, D. Iniciativas Apasionantes. Available online: https://www.damoslacara.com/iniciativas-apasionantes/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- La Cara, D. Quiénes Somos. Available online: https://www.damoslacara.com/quienes-somos/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Instituto de la Empresa Familiar. Las Empresas Familiares Impulsan el Movimiento #DamoslaCara. 11 de junio de 2020. Available online: https://www.iefamiliar.com/noticia/las-empresas-familiares-impulsan-el-movimiento-damoslacara/ (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Gómez, A.D. The key elements of viral advertising. From motivation to emotion in the most shared videos. Comunicar. Media Educ. Res. J. 2014, 22, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Instituto de la Empresa Familiar, KPMG & STEP Project. Informe de Empresa Familiar 2021. 2021. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/es/pdf/2021/06/informe-empresa-familiar-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- La Vanguardia. Fundación Osborne Dona 200 Kilos de Material médico Para Luchar Contra el Coronavirus en China. Available online: https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20200304/473964629346/economiaempresas-fundacion-osborne-dona-200-kilos-de-material-medico-para-luchar-contra-el-coronavirus-en-china.html (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Erdogan, I.; Rondi, E.; De Massis, A. Managing the tradition and innovation paradox in family firms: A family imprinting perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 20–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jabeen, F.; Faisal, M.N.; Al Matroushi, H.; Farouk, S. Determinants of innovation decisions among Emirati female-owned small and medium enterprises. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 11, 408–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xifra, J. Comunicación corporativa, relaciones públicas y gestión del riesgo reputacional en tiempos del COVID-19. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Esmael, B.; Talib, F.; Faisal, M.N.; Jabeen, F. Socially responsible supply chain management in small and medium enterprises in the GCC. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; García-Sánchez, A. Corporate social responsibility during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Al-Sultan, K.; De Massis, A. Corporate social responsibility in family firms: A systematic literature review. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kim, M.; Qian, C. Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Financial Performance: A Competitive-Action Perspective. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1097–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, M.A.; Banerjee, S.N.; Rasheed, A.A. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: A theory of dual responsibility. Manag. Decis. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivo-López, E.; Villanueva-Villar, M.; Novoa-Santos, S.; Doval-Ruiz, M.I. Does COVID-19 Change CSR? A Family Business Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413954

Rivo-López E, Villanueva-Villar M, Novoa-Santos S, Doval-Ruiz MI. Does COVID-19 Change CSR? A Family Business Perspective. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413954

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivo-López, Elena, Mónica Villanueva-Villar, Sofía Novoa-Santos, and María Isabel Doval-Ruiz. 2021. "Does COVID-19 Change CSR? A Family Business Perspective" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413954

APA StyleRivo-López, E., Villanueva-Villar, M., Novoa-Santos, S., & Doval-Ruiz, M. I. (2021). Does COVID-19 Change CSR? A Family Business Perspective. Sustainability, 13(24), 13954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413954