The Booming Number of Museums and Their Inequality Changes in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Collection

3. Calculations

Inequality

4. Scale Law and Allometric Relationships

5. Results

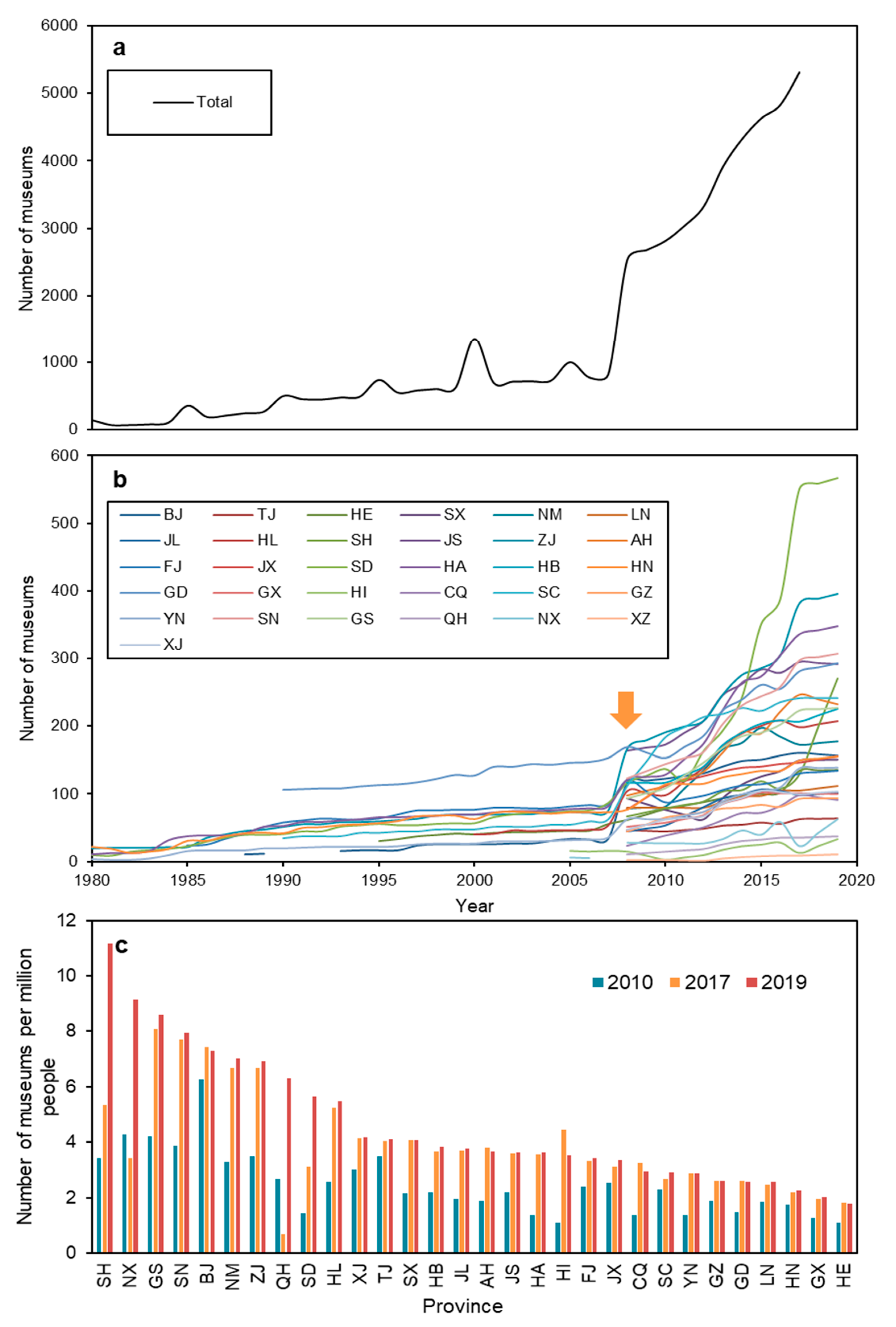

5.1. Historical Trends of the Number of Museums

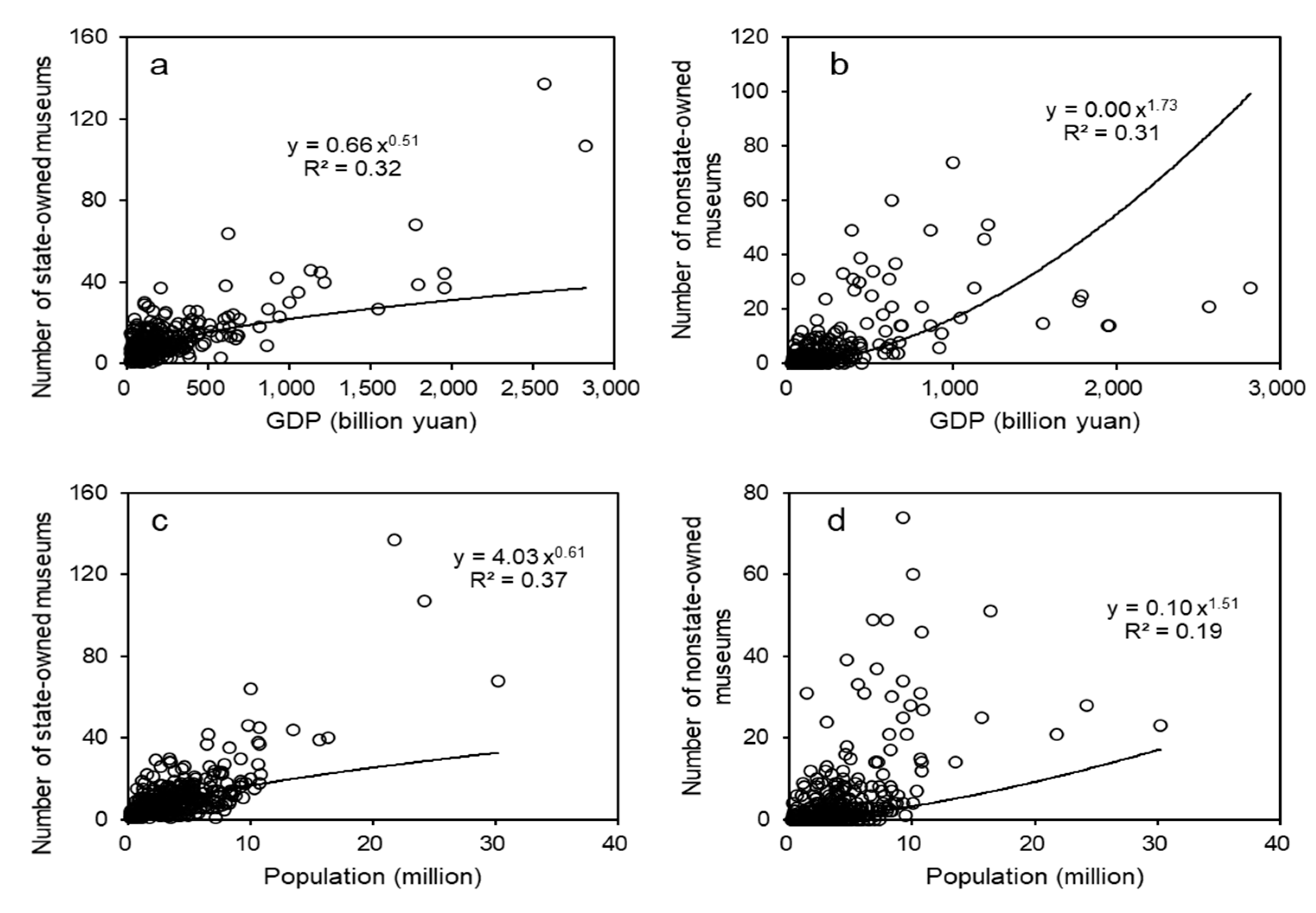

5.2. Scale Law of the Number of Museums and Local Population

5.3. Relationships between the Number of Visitors and the Number of Museums

5.4. Historical Changes in the Gini Coefficient of the per Capita Number of Museums

5.5. Relationship between Inequality and Socioeconomic Development

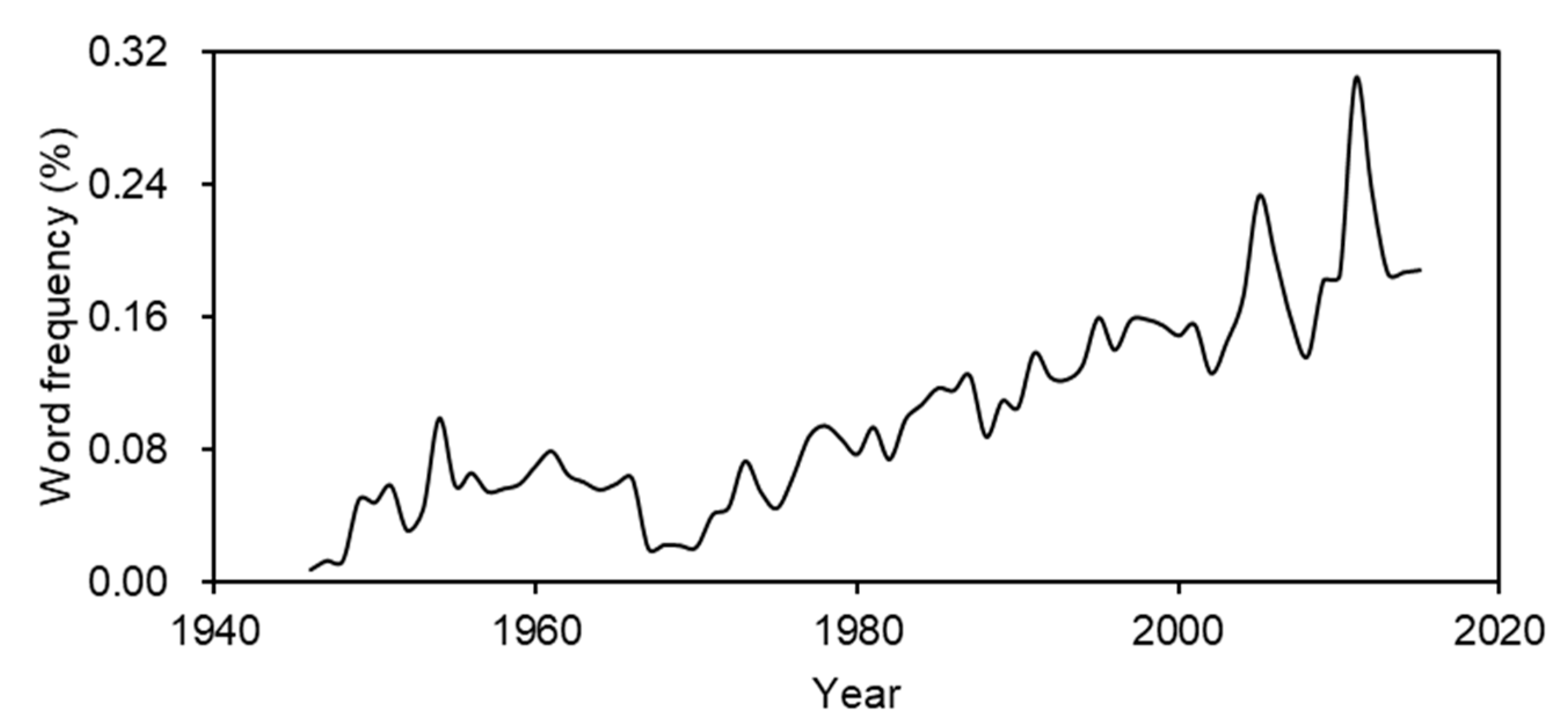

5.6. Public Attention Regarding the Museums

6. Discussion

6.1. The Museum Boom Still Lags behind Population and Economic Development

6.2. The Museum Agglomeration Effect Promotes Visits to Museums

6.3. The Number of Museums among Provinces Is Relatively Equal, but Gini among Cities Needs to Be Improved

6.4. Museum Development Synergizes with Economic Growth and Human Well-Being

6.5. Limitations and Uncertainties

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Council of Museums. History of ICOM. 2021. Available online: https://icom.museum/en/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Pietro, L.D.; Mugion, R.G.; Renzi, M.F.; Toni, M. An Audience-Centric Approach for Museums Sustainability. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5745–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denton, K.A. Museums, Memorial Sites and Exhibitionary Culture in the People’s Republic of China. China Q. 2005, 183, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, T. Blue Book of China’s Economy; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Culture. Museéofile, Directory of Museums in France. 2021. Available online: http://traduction.culture.gouv.fr/url/Result.aspx?to=en&url=https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Espace-documentation/Bases-de-donnees (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Museums Association. How Many Museums Are There in the UK? 2021. Available online: https://www.museumsassociation.org/about/faqs/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Institute of Museum and Library Services. The Museum Data Files. 2018. Available online: https://www.imls.gov/research-evaluation/data-collection/museum-data-files (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Tahmasbi, B.; Mansourianfar, M.H.; Haghshenas, H.; Kim, I. Multimodal accessibility-based equity assessment of urban public facilities distribution. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsley, R.P. Inclusion in museums: A matter of social justice. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2016, 31, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, F.; Lu, L.; Yu, P. The spatial agglomeration of museums, a case study in London. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Rostami, F.; Alizadeh, B. Is inequality in the distribution of urban facilities inequitable? Exploring a method for identifying spatial inequality in an Iranian city. Cities 2016, 52, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yan, S. A quantitative analysis of inequality of urban cultural space distribution in Xi’an. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2019, 62, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun-Cheng, L.S.C. Distance Decay. In International Encyclopedia of Geography; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, T.; Drezner, Z.; Zerom, D. Facility Dependent Distance Decay in Competitive Location. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2020, 20, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Haase, D. Green justice or just green? Provision of urban green spaces in Berlin, Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 122, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspadori, P. Inequality and culture: Geographical differences in the access to cultural enrichment in Italy (1863–1992). Contin. Chang. 2011, 26, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hek, M.A.; Kraaykamp, G. Cultural consumption across countries: A multi-level analysis of social inequality in highbrow culture in Europe. Poetics 2013, 41, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veal, A.J. Leisure, income inequality and the Veblen effect: Cross-national analysis of leisure time and sport and cultural activity. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lusseau, D.; Mancini, F. Income-based variation in Sustainable Development Goal interaction networks. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olaiya, H.B.A. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development & International Decade for People of African Descent. 2015. Available online: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/801754 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Moll, B.; Townsend, R.M.; Zhorin, V. Economic Development, Flow of Funds and the Equilibrium Interaction of Financial Frictions. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2013, 114, 6176–6184. [Google Scholar]

- Brelsford, C.; Lobo, J.; Hand, J.; Bettencourt, L.M.A. Heterogeneity and scale of sustainable development in cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8963–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eliazar, I. Harnessing inequality. Phys. Rep. 2016, 649, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zheng, X.; Wei, C. Measurement of inequality using household energy consumption data in rural China. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoff, T.; Sosič, R.; Hicks, J.L.; King, A.C.; Delp, S.L.; Leskovec, J. Large-scale physical activity data reveal worldwide activity inequality. Nature 2017, 547, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, Y.; Ren, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, C. Inequality in the distribution of health resources and health services in China: Hospitals versus primary care institutions. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lazzeretti, L. The resurge of the “societal function of cultural heritage”. An introduction. City Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Capone, F. Museums as Societal Engines for Urban Renewal. The Event Strategy of the Museum of Natural History in Florence. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1548–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jang, S. To cluster or not to cluster? Understanding geographic clustering by restaurant segment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuschnigg, M. Scaling trajectories of cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 13759–13761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, A.; Berridge, G.; Kim, C. The Urban Museum as a Creative Tourism Attraction: London Museum Lates Visitor Motivation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudio-Pachecano, L.; Larralde, H. Agglomeration or separation: Store patterns through an optimal location model. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2020, 542, 123366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Williams, A.M.; Park, S.; Chen, J.L. Spatial spillovers of agglomeration economies and productivity in the tourism industry: The case of the UK. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cultural Heritage Administration of China. National Museum Directory. 2021. Available online: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/index.html (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- The Statistical Yearbook for Provinces. China National Knowledge Infrastructure. 2021. Available online: Data.cnki.net/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- China Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistic Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Ni, P.F. (Ed.) Annual Report on China’s Urban Competitiveness (No.14); Beijing-Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Jin, C. Report of China’s Urban Health Life; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lansdall-Welfare, T.; Sudhahar, S.; Thompson, J.; Lewis, J.; FindMyPast Newspaper Team; Cristianini, N. Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E457–E465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xun, E.; Rao, G.; Xiao, X.; Zang, J. The construction of the BCC Corpus in the age of Big Data. Corpus Linguist. 2016, 3, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt, L.M.A.; Lobo, J.; Helbing, D.; Kühnert, C.; West, G.B. Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7301–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bettencourt, L.M.A. The Origins of Scaling in Cities. Science 2013, 340, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.; Wei, Y.D. Spatial inequality of foreign direct investment in China: Institutional change, agglomeration economies, and market access. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 69, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnert, C.; Helbing, D.; West, G.B. Scaling laws in urban supply networks. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2006, 363, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirelles, J.; Neto, C.R.; Ferreira, F.F.; Ribeiro, F.L.; Binder, C.R. Evolution of urban scaling: Evidence from Brazil. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qian, J.-H.; Yang, C.-H.; Han, D.-D.; Ma, Y.-G. Multi-scaling mix and non-universality between population and facility density. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2012, 391, 5146–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowitz, E.; Ibenholt, K. Economic impacts of cultural heritage—Research and perspectives. J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanziola, J.; Méndez-Carbajo, D. Economic growth, government expenditure and income: The case of museums and libraries in England. Cult. Trends 2011, 20, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aratuo, D.N.; Etienne, X.L. Industry level analysis of tourism-economic growth in the United States. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensenat, E.C. Beyond City Size: Characterizing and Predicting the Location of Urban Amenities. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Um, J.; Son, S.; Lee, S.; Jeong, H.; Kim, B.J. Scaling laws between population and facility densities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14236–14240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, R.; Zhong, S.; He, A. Disaster Impact, National Aid, and Economic Growth: Evidence from the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Tao, Z. Evaluating China’s Paired-Assistance Policy (PAP) in Response to the Wenchuan Earthquake: A Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pop, I.L.; Borza, A. Factors Influencing Museum Sustainability and Indicators for Museum Sustainability Measurement. Sustainability 2016, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monteagudo-Fernández, J.; Gómez-Carrasco, C.J.; Chaparro-Sainz, Á. Heritage Education and Research in Museums. Conceptual, Intellectual and Social Structure within a Knowledge Domain (2000–2019). Sustainability 2021, 13, 6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, X. Income inequality in today’s China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6928–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rubin, J. (Ed.) TEA/AECOM 2018 Theme Index and Museum Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report; Themed Entertainment Association (TEA): Burbank, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pumain, D.; Rozenblat, C. Two metropolisation gradients in the European system of cities revealed by scaling laws. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1645–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Du, Y.; Shang, L.; Ge, Y.; Chang, J.; Yang, G. The Booming Number of Museums and Their Inequality Changes in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413860

Chang X, Wu Z, Chen Y, Du Y, Shang L, Ge Y, Chang J, Yang G. The Booming Number of Museums and Their Inequality Changes in China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413860

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Xianyuan, Zhaoping Wu, Yi Chen, Yuanyuan Du, Longfei Shang, Ying Ge, Jie Chang, and Guofu Yang. 2021. "The Booming Number of Museums and Their Inequality Changes in China" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413860

APA StyleChang, X., Wu, Z., Chen, Y., Du, Y., Shang, L., Ge, Y., Chang, J., & Yang, G. (2021). The Booming Number of Museums and Their Inequality Changes in China. Sustainability, 13(24), 13860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413860