Readiness Assessment for IDE Startups: A Pathway toward Sustainable Growth

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Readiness Levels (RLs): Background and Application

3. Research Methodology: Development and Validity

3.1. Preparing Questions for Interviews and Focus Group Discussions

3.2. Conducting In-Depth Interviews

3.3. Designing the Readiness Assessment Framework

3.4. Testing the Content Validity of the RL Framework

3.5. Conducting Focus Group Discussions and Developing the Readiness Assessment Tool

3.6. Testing the Applicability of the Readiness Assessment Tool

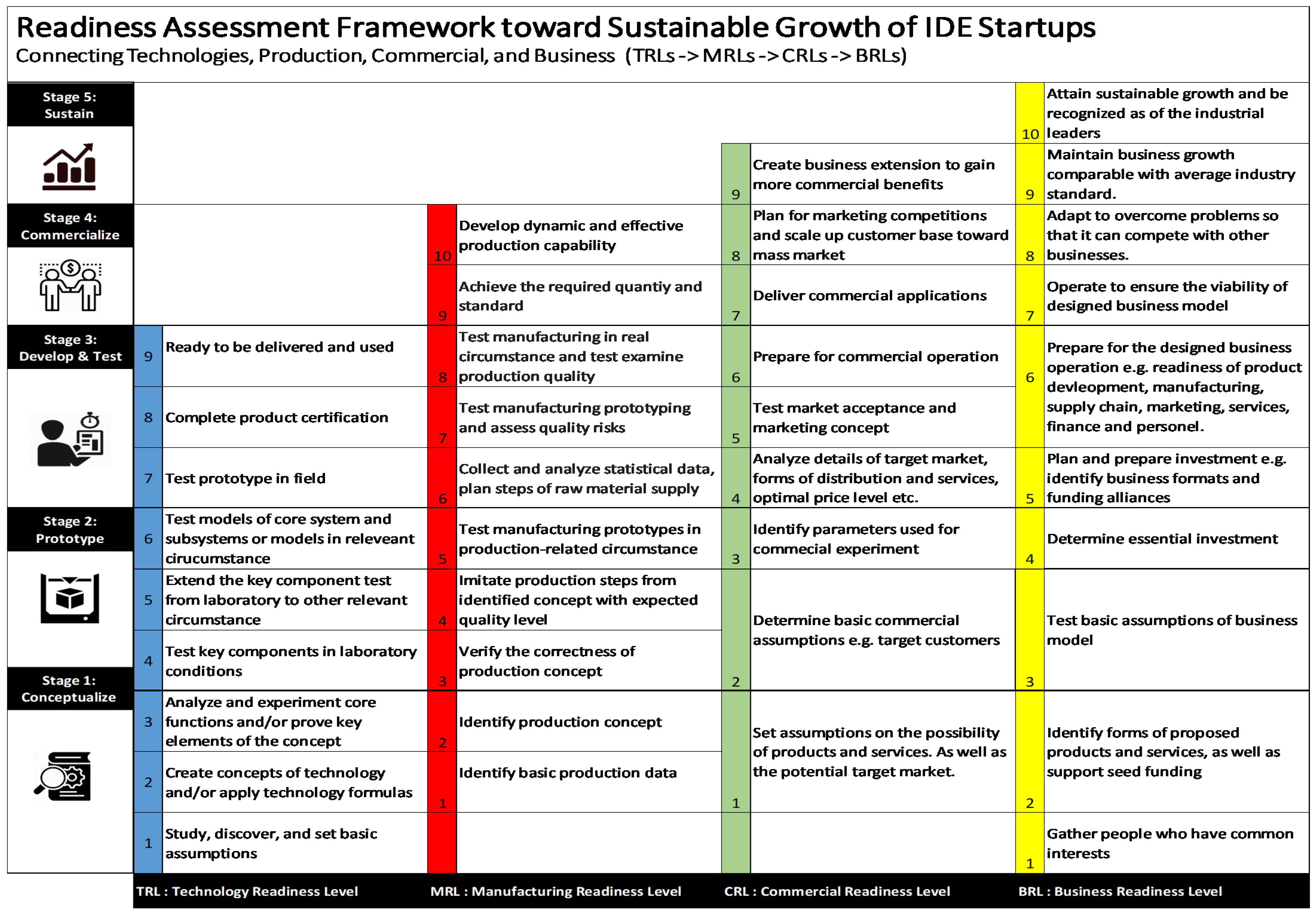

4. The Development of the Readiness Assessment Framework

5. The Description of the Readiness Assessment Framework for IDE Startups

5.1. Dimension 1: Technology Readiness Level (TRL)

5.2. Manufacturing Readiness Level (MRL)

5.3. Dimension 3: Commercial Readiness Level (CRL)

5.4. Dimension 4: Business Readiness Level (BRL)

6. Case Demonstration of the Application of the Readiness Assessment Tool for IDEs

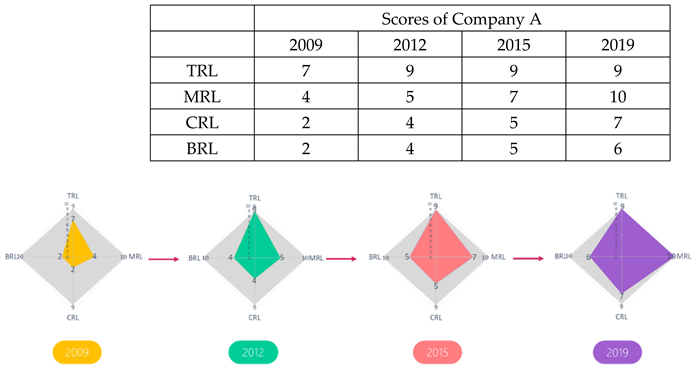

Case 1: Company A

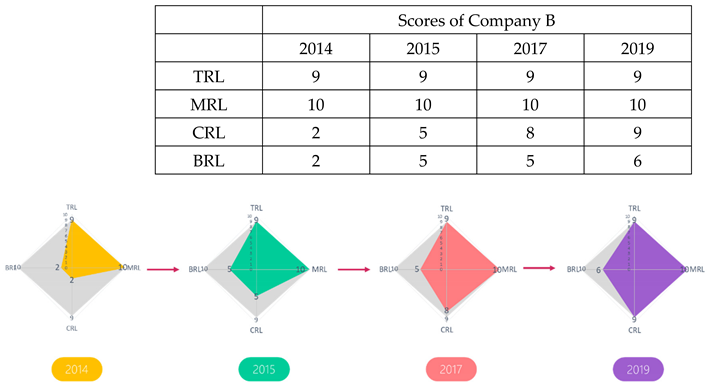

Case 2: Company B

Case 3: Company C

7. Discussion: Managerial Implications

8. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Examples of Questions to Assess Readiness Levels

| Questions To Assess Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) Topic 1: the observation of development fundamentals.

|

| Questions To Assess Manufacturing Readiness Levels (MRLs) Topic 1: the identification of material qualifications.

|

| Questions To Assess Commercial Readiness Levels (CRLs) Topic 1: readiness for commercial management.

|

| Questions To Assess Business Readiness Levels (BRLs) Topic 1: readiness for business management.

|

References

- Azizian, N.; Sarkani, S.; Mazzuchi, T. A comprehensive review and analysis of maturity assessment approaches for improved decision support to achieve efficient defense acquisition. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–22 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, P.B. Quality Is Free: The Art of Making Quality Certain; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, W.; Kruse, R. Readiness Level Proliferation, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base; Air Force Research Laboratory: Fairborn, OH, USA, 2011; Available online: http://www.dtic.mil/ndia/2011system/13132_NolteWednesday.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Huang, Z.; Farrukh, C.; Shi, Y. Commercialisation Journey in Business Ecosystem: From Academy to Market. In Entrepreneurial, Innovative and Sustainable Ecosystems. Applying Quality of Life Research (Best Practices); Leitão, J., Alves, H., Krueger, N., Park, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Craver, J. Technology Program Management Model (TPMM) Overview; Army Space and Missile Defense Technical Center Huntsville Al: 2006. Available online: https://ndiastorage.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/ndia/2006/systems/Thursday/crave.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Persons, T.M.; Mackin, M. Technology Readiness Assessment Guide: Best Practices for Evaluating the Readiness of Technology for Use in Acquisition Programs and Projects; US Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, T.; Eppinger, S.; Joglekar, N.; Olechowski, A. Using TRLs and system architecture to estimate technology integration risk. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 17), Volume 3: Product, Services and Systems Design, DS 87-3, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Niimbl. Manufacturing Readiness Level (MRL) Guidance Document. Available online: https://niimbl.org/Downloads/MRLGuidance.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2018).

- Canada, X.R.C.O. NRC-XRCC Business Alliance. Available online: https://xrcc.external.xerox.com/news/nrc-xrcc-collaboration-and-creation-of-new-national-laboratory-on-the-xrcc-campus/ (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Council, E.PS.RC. The Funding Landscape. n.d. Available online: https://epsrc.ukri.org/research/ourportfolio/themes/healthcaretechnologies/strategy/toolkit/landscape/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Denis Duret, L.T.; Fillon, B.; Egger, H.; Agullo, J.V. Barriers and Success Factors; Commercialisation Readiness Scale. 2009. Available online: http://nanofutures.eu/sites/default/files/Barriers-and-Success-Factors_CommercialisationReadinessScale_20092012_final_.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2018).

- Government, A. Commercial Readiness Index for Renewable Energy Sectors. 2014. Available online: https://arena.gov.au/assets/2014/02/Commercial-Readiness-Index.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- KIBO. Korea Technology Finance Corporation (KOTEC)—Company Overview. 2020. Available online: https://www.kibo.or.kr:444/src/english/about/koa100.asp (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Kotec. Overview of KOTEC’s Credit Guarantee Scheme. Available online: https://www.kibo.or.kr/english/work/work010100.do (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- H., P. Supporting Innovative SME in Korea. n.d. Available online: https://www.kibo.or.kr/english/work/work020603.do (accessed on 4 November 2018).

- Rene Wintjes, J.L.; Dachs, B.; Georg, Z.; Zhao, Y. China’s STI Policies and Framework Conditions. 2014. Available online: http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/delegations/china/documents/eu_china/research_innovation/4_innovation/chinas_sti_policies_framework_conditions.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Department of Industrial Technology (DoIT) of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA). Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI). (n.d.). Available online: https://www.moea.gov.tw/MNS/doit_e/content/Content.aspx?menu_id=21148 (accessed on 4 November 2018).

- Hammarberg, K.; Kirkman, M.; de Lacey, S. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Technology Readiness Levels Demystified. August 2010. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/topics/aeronautics/features/trl_demystified.html (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Heder, M. From NASA to EU: The evolution of the TRL scale in public sector innovation. Innov. J. 2017, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Research Management and Development Division, M.U. TRL Level 1–9. Available online: https://op.mahidol.ac.th/ra/contents/research_fund/GOVERN-2563/04_Technology%20Readiness%20Level-TRL.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Sadin, S.R.; Povinelli, F.P.; Rosen, R. The NASA technology push towards future space mission systems. Acta Astronaut. 1989, 20, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, D.D. Commercial Readiness Index Assessment. May 2017. Available online: http://iea-retd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/170515-RE-CRI-RETD-de-Jager.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Bhattacharyya, R.B.A.B. Why Most Entrepreneurs Hate Fundraising—And How to Fix It. 2017. Available online: https://medium.com/village-capital/entrepreneurs-and-vcs-need-to-be-more-precise-in-the-way-they-talk-to-each-other-3e714e7a5245 (accessed on 4 November 2018).

- Starbuck, W.H.; Milliken, F.J. Challenger: Fine-tuning the odds until something breaks. J. Manag. Stud. 1988, 25, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdsri, N.; Assakul, A.; Vatananan, R. Applying change management approach to guide the implementation of technology roadmapping (TRM). In Proceedings of the Portland International Conference in Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), Cape Town, South Africa, 27–31 July 2008; pp. 2134–2140. [Google Scholar]

- Kockan, I.; Daim, T.U.; Gerdsri, N. Roadmapping future powertrain technologies: A case study of Ford Otosan. Int. J. Technol. Policy Manag. 2010, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdsri, N.; Puengrusme, S.; Vatananan, R.; Tansurat, P. Conceptual framework to assess the impacts of changes on the status of a roadmap. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2019, 52, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutivongse, N.; Gerdsri, N. Creating an innovative organization: Analytical approach to develop a strategic roadmap guiding organizational development. J. Model. Manag. 2019, 15, 50–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Cheng, Y.; Su, X. Research on the Sustainability of the Enterprise Business Ecosystem from the Perspective of Boundary: The China Case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdsri, N.; Iewwongcharoen, B.; Rajchamaha, K.; Manotungvorapun, N.; Pongthanaisawan, J.; Witthayaweerasak, W. Capability Assessment toward Sustainable Development of Business Incubators: Framework and Experience Sharing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intarakumnerd, P.; Gerdsri, N.; Teekasap, P. The roles of external knowledge sources in Thailand’s automotive industry. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2012, 20 (Suppl. S1), 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdsri, N.; Kongthon, A.; Puengrusme, S. Profiling the Research Landscape in Emerging Areas Using Bibliometrics and Text Mining: A Case Study of Biomedical Engineering (BME) in Thailand. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2017, 14, 1740011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intarakumnerd, P.; Gerdsri, N. Implications of technology management and policy on the development of a sectoral innovation system: Lessons learned through the evolution of Thai automotive sector. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2014, 11, 1440009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro-Mojica, J.; Fernandez, R. Review paper on the future of the food sector through education, capacity building, knowledge translation and open innovation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 38, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manotungvorapun, N.; Gerdsri, N. Complementarity vs. Compatibility: What is really matter for Open Innovation partner selection? Int. J. Transit. Innov. Syst. 2016, 5, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manotungvorapun, N.; Gerdsri, N. University–Industry Collaboration: Assessing the Matching Quality Between Companies and Academic Partners. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019, 68, 1418–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manotungvorapun, N.; Gerdsri, N. Positioning academic partners to align with proper modes of university-industry collaboration. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2021, 24, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdsri, N.; Manotungvorapun, N. Systemizing the management of university-industry collaboration (UIC): Assessment and Roadmapping. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Awano, H.; Tsujimoto, M. The Mechanisms for Business Ecosystem Members to Capture Part of a Business Ecosystem’s Joint Created Value. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Facilitating Organization (Country) [Source] | Dimension of Readiness | Target Organizations | Purpose of Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| US Government Accountability Office (GAO) (U.S.A.) [7] | Technology Readiness | Federal agencies | To evaluate the maturity of technologies, in order to make decisions on acquisition programs and projects. |

| The United States Department of Defense (DoD) [8] | Technology Readiness | Industries | To apply for risk analysis. |

| The NIIMBL project, as part of the Manufacturing USA network (U.S.A.) [9] | Manufacturing Readiness | Government, universities and industries | To support project funding for accelerating biological innovation and fill the gap in manufacturing innovation among target organizations. |

| Governmental agencies (Canada) [10] | Technology Readiness | Industrial firms | To support mentoring on research funding and budget. |

| The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (U.K.) [11] | Technology Readiness | Organizations in technology and innovation networks | To support advisory roles in issues of research funding, technology, and innovation development, as well as to promote technology and innovation networks. |

| Nano Com (the EU countries) [12] | Marketing, manufacturing, technology and investment Readiness | Industrial companies | To detect barriers in marketing, manufacturing, technology, and investment. |

| The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) (Australia) [13] | Commercial (namely Commercial Readiness Index) | Industrial companies | To evaluate commercial readiness in renewable energy technology. |

| KOTEC (Korea Technology Finance Corporation) (South Korea) [14] | Technology, marketing, commerce and any factors affecting the economy | Technology-based companies | To support risk evaluation and technology valuation. |

| Science Technology and Innovation Performance of China (STI China) (China) [17] | Technology and Business Readiness | Industrial firms and academia | To support activities of evaluation, accreditation, ranking, and rating protocols for benchmarking. |

| Department of Industrial Technology (DoIT), the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) (Taiwan) [18] | Technology Readiness | Academia and research institutes under Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) | To promote research and to develop marketable products. |

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

Stage 5: Sustain | The enterprise is moving toward sustainable growth and envisions becoming the industry leader. New or existing product development is continually being planned. |

| Stage 4: Commercialize  | The enterprise has achieved product development and market expansion. Upscaling for business growth is being planned and requires additional monetary support. Financing is also concentrated. |

Stage 3: Develop & Test | The enterprise has undertaken development and testing efforts. The usability of the product has been confirmed. The supply chain and distribution efforts are being managed. |

| Stage 2: Prototype  | The enterprise has developed the product concept, reinforced with technological feasibility. Business registration has been achieved. However, prototyping is still being processed. The enterprise is stepping up its development and testing efforts. |

| Stage 1: Conceptualize  | The enterprise has been established. The product concept has been designed, but the technological feasibility is still being verified. The market viability or business potential is being researched. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerdsri, N.; Manotungvorapun, N. Readiness Assessment for IDE Startups: A Pathway toward Sustainable Growth. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413687

Gerdsri N, Manotungvorapun N. Readiness Assessment for IDE Startups: A Pathway toward Sustainable Growth. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413687

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerdsri, Nathasit, and Nisit Manotungvorapun. 2021. "Readiness Assessment for IDE Startups: A Pathway toward Sustainable Growth" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413687

APA StyleGerdsri, N., & Manotungvorapun, N. (2021). Readiness Assessment for IDE Startups: A Pathway toward Sustainable Growth. Sustainability, 13(24), 13687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413687