Why Do UNESCO Biosphere Reserves Get Less Recognition than National Parks? A Landscape Research Perspective on Protected Area Narratives in Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Protected Areas as a Way of Conceptualising Human-Nature Relationships

2. Theoretic Background on Landscape, Protected Areas, and Narratives

2.1. Difficulties in Comparing Biosphere Reserves and National Parks

2.2. Perspectives of Landscape Research on Protected Areas

2.3. Protected Areas and Narratives

2.4. The Analysis of Narratives

- Actors—narratives are more successful when they are communicated by actors who are recognised by the public as legitimate spokespersons. These do not have to be people with authority in the traditional sense. Thus, the Fridays for Future movement has gained particular weight due to the fact that it is pupils and students that are fighting for their future and accusing the older generation of irresponsible behaviour.

- Connectivity—narratives are more successful when they fit into a dominant discourse and into the recipients existing set of attitudes. Connectivity is greatly influenced by metaphor. It makes a difference whether one speaks of global warming, climate change, or climate crisis [49], or uses disease metaphors that relate to everyday experiences such as: “The earth has a fever” [49] because each of these formulations triggers different associations.

- Openness and ambiguity—narratives are more successful when they are open and ambiguous. An impressive example is the rise of the term “biodiversity”. As Takacs was able to show, even among the originators of this term there are different ideas of what exactly biodiversity means and should mean [66]. Ecologist David Ehrenfeld is quoted by Takacs saying: “I think it‘s one of those wonderful catchwords like sustainable development, that, because it‘s vaguely defined, has a broad appeal” [66].

- Communicability—narratives must be communicable. Narratives are easy to communicate if they have a comprehensible plot; for example, a clear definition of the problem that also makes a possible solution apparent, a comprehensible juxtaposition of good and evil as well as the acting personnel: hero, anti-hero, helper, gate-keeper.

3. Results

3.1. National Parks: Leaving Space for Nature

- Size: National parks are usually very large protected areas.

- They are usually associated with wilderness and the absence of human impact on the landscape.

- They are established at the highest political level, which gives weight and permanence to the endeavour.

- They are associated with tourism from the beginning.

- There are multiple justifications for protection: aesthetically monumental, species diversity, function as a learning and experience space for a society increasingly disconnected from nature.

- The term national park itself: The protected area is regarded as being of national importance.

3.1.1. Parkifying: Creating the National Park Experience

3.1.2. What Is Constituting the National Park Narrative and How Does It Fulfil the Above-Mentioned Success Factors for Narratives?

- National parks are places with special value and places of national importance. → National parks are treasures.

- Nature has a (spiritual) value. → National parks stand for value in nature.

- National parks interpret nature through education, marked trails, visitor centres, etc., (parkification). → National parks stand for great experiences.

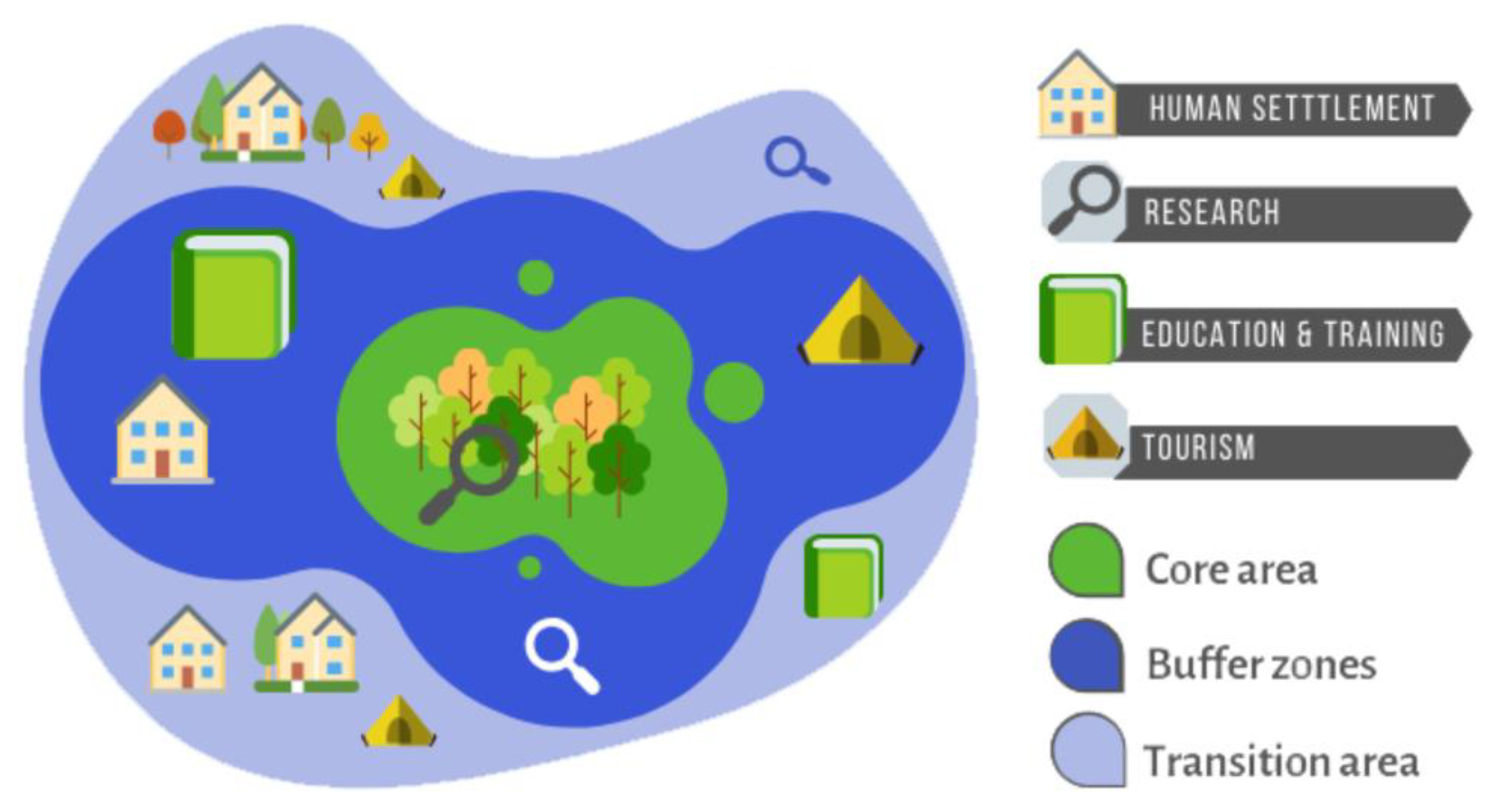

3.2. Biosphere Reserves: Reconciliation of Nature and Humans

3.2.1. Biosphere Reserves and the Cultural Landscape Narrative

3.2.2. Biosphere Reserves as Innovative Places

3.2.3. The “Thing“ with the Reserve

3.2.4. How Can the Narrative of Biosphere Reserves Be Characterised and Does It Fulfil the Above-Mentioned Success Factors for Narratives?

- Biosphere reserves stand for sustainable development.

- Biosphere reserves stand for landscapes used by people.

- Biosphere reserves stand for participation and local solutions.

- Biosphere reserves stand for international cooperation.

- From this perspective, biosphere reserves stand for tradition and cultural landscapes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Which Narrative for Protected Areas and Sustainable Development?

- They must mobilise communities.

- They need to be visible politically in order to receive support and funding and be taken into account in the implementation of other relevant policies.

4.2. How to Innovate and Preserve Tradition at the Same Time?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perceptions, Attitudes, and Values; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. First Detailed Draft of the New Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framwork. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/article/draft-1-global-biodiversity-framework (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- European Commission. Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Maxwell, S.L.; Cazalis, V.; Dudley, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stolton, S.; Visconti, P.; Woodley, S.; Kingston, N.; Lewis, E.; et al. Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature 2020, 586, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, G.M. Whose conservation? Science 2014, 345, 1558–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N.; Yung, L. Beyond Naturalness. Rethinking Park and Wilderness Stewardship in an Era of Rapid Change; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shultis, J.; Heffner, S. Hegemonic and emerging concepts of conservation: A critical examination of barriers to incorporating Indigenous perspectives in protected area conservation policies and practice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1227–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, K.L.; Witkowski, E.T.F.; Erasmus, B.F.N. Reviewing Biosphere Reserves globally: Effective conservation action or bureaucratic label? Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2014, 89, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G.; Price, M. (Eds.) Editors Introductory. In UNESCO Biosphere Reserves: Supporting Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability and Society; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; de La Vega-Leinert, A.C.; Schultz, L. The role of community participation in the effectiveness of UNESCO Biosphere Reserve management: Evidence and reflections from two parallel global surveys. Envir. Conserv. 2010, 37, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgewater, P.B. Biosphere reserves: Special places for people and nature. Environ. Sci. Policy 2002, 5, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G. The contributions of UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme and biosphere reserves to the practice of sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishwaran, N.; Persic, A.; Tri, N.H. Concept and practice: The case of UNESCO biosphere reserves. IJESD 2008, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, A.D.; Reed, M.G.; Måren, I.E.; Price, M.F.; Moreira-Muñoz, A.; Coetzer, K. Recognize 727 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves for biodiversity COP15. Nature 2021, 598, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit (BMU). Naturbewusstsein 2019: Bevölkerungsumfrage zu Natur und biologischer Vielfalt; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.E.; Daniels, S. (Eds.) Editors Introductory. In The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, J.; Duncan, N. (Re)Reading the Landscape. Env. Plan D 1988, 6, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, O. Landscape Theories: A Brief Introduction; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Landscape and Power in Geographical Space as a Social-Aesthetic Construct; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, G.; Pfister, H.-R.; Salway, A.; Fløttum, K. Remembering and Communicating Climate Change Narratives—The Influence of World Views on Selective Recollection. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, M.D. Cultural Characters and Climate Change: How Heroes Shape Our Perception of Climate Science. Soc. Sci. Q. 2014, 95, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; Song, G. Making Sense of Climate Change: How Story Frames Shape Cognition. Political Psychol. 2014, 35, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.; Brown, K.; Dessai, S.; de França, D.M.; Haynes, K.; Vincent, K. Does tomorrow ever come? Disaster narrative and public perceptions of climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 2006, 15, 435–457. [Google Scholar]

- Bushell, S.; Colley, T.; Workman, M. A unified narrative for climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 971–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, A. Are we sacrificing the future of coral reefs on the altar of the “climate change” narrative? ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2020, 77, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.; Adams, W.M.; Murombedzi, J.C. Back to the Barriers? Changing Narratives in Biodiversity Conservation. Forum Dev. Stud. 2005, 32, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gißibl, B. Der erste Transnationalpark Deutschlands. In Urwald der Bayern: Geschichte, Politik und Natur im Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald; Heurich, M., Mauch, C., Eds.; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2020; pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Michler, T.; Aschenbrand, E. “Natur Natur sein lassen”. In Urwald der Bayern: Geschichte, Politik und Natur im Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald; Heurich, M., Mauch, C., Eds.; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2020; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/PAG-021.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Dudley, N.; Stolton, S. Leaving Space for Nature: The Critical Role of Area Based Conservation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.E.; Daniels, S. Iconography and Landscape. In The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments; Cosgrove, D.E., Daniels, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Distinktion—Macht—Landschaft: Zur sozialen Definition von Landschaft, 1st ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/GWV Fachverlage GmbH, Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Landscape Convention. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016807b6bc7 (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Thompson, C.W. Landscape perception and environmental psychology. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Howard, P., Thompson, I.H., Waterton, E., Atha, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, J.S.; Duncan, N.G. The Aestheticization of the Politics of Landscape Preservation. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2001, 91, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; Hill, R.; Chan, K.M.A.; Baste, I.A.; Brauman, K.A.; et al. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science 2018, 359, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Groot, R.; Costanza, R.; Braat, L.; Benjamin, B.L.; Carrasco, L.; Crossman, N.; Egoh, B.; Geneletti, D.; Hansjuergens, B.; Hein, L.; et al. RE: Ecosystem Services are Nature’s Contributions to People: Highwire Comment Response to: Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Available online: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/re-ecosystem-services-are-nature%E2%80%99s-contributions-people (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; Hill, R.; Chan, K.M.A.; Baste, I.A.; Brauman, K.A.; et al. RE: There is more to Nature’s Contributions to People than Ecosystem Services—A response to de Groot et al.: Highwire Comment Response to: Assessing Nature’s Contributions to People. Available online: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/re-there-more-nature%E2%80%99s-contributions-people-ecosystem-services-%E2%80%93-response-de-groot-et-al (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Kadykalo, A.N.; López-Rodriguez, M.D.; Ainscough, J.; Droste, N.; Ryu, H.; Ávila-Flores, G.; Le Clec’h, S.; Muñoz, M.C.; Nilsson, L.; Rana, S.; et al. Disentangling ‘ecosystem services’ and ‘nature’s contributions to people’. Ecosyst. People 2019, 15, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Başak Dessane, E.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: The IPBES approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brockington, D. Data, Myths and Narratives: The Challenges of the Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: http://siid.group.shef.ac.uk/data-myths-narratives-challenges-sustainable-development-agenda/ (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Viehöver, W. Diskurse als Narrationen. In Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Diskursanalyse; Keller, R., Hirseland, A., Schneider, W., Viehöver, W., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2001; pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Somers, M.R. The narrative constitution of identity: A relational and network approach. Theory Soc. 1994, 23, 605–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, O.J. Consciousness Reconsidered, 3rd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Identity: Contemporary Identity Politics and the Struggle for Recognition; Profile Books: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by: With a New Afterword, 6th ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environ. Commun. 2010, 4, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadinger, F.; Jarzebski, S.; Yildiz, T. Politische Narrative. Konturen einerpolitikwissenschaftlichen Erzähltheorie. In Politische Narrative: Konzepte—Analysen—Forschungspraxis; Gadinger, F., Jarzebski, S., Yildiz, T., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kelle, U. Mixed methods. In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, 2nd ed.; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. IUCN Category II: National Park. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/theme/protected-areas/about/protected-areas-categories/category-ii-national-park (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Keenleyside, K.; Dudley, N.; Cairns, S.; Hall, C.; Stolton, S. Ecological Restoration for Protected Areas. Principles, Guidelines and Best Practices; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C. Managing Conflicts in Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilijević, M.; Zunckel, K.; McKinney, M.; Erg, B.; Schoon, M.; Rosen Michel, T. Transboundary Conservation: A Systematic and Integrated Approach. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Woodley, S.; Bertzky, B.; Crawhall, N.; Dudley, N.; Miranda Lonono, J.; MacKinnon, K.; Redford, K.; Sandwith, T. Meeting Aichi Target 11: What does sucess look like for protected area systems? PARKS 2012, 18, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, S.H. Qualitative Analyse von Chats und anderer User-generierter Kommunikation. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung, 2nd ed.; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 1041–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, R.; Waters, J. The Hidden Internationalism of Elite English Schools. Sociology 2015, 49, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinwall, A. Naturalness or Biodiversity: Negotiating the Dilemma of Intervention in Swedish Protected Area Management. Environ. Values 2015, 14, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, L.; Regnéll, J. Nature, culture and time: Contested landscapes among environmental managers in Skåne, southern Sweden. In Peopled Landscapes: Archaeological and Biogeographic Approaches to Landscapes; Haberle, S.G., David, B., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H.; Rubin, I. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Girtler, R. 10 Gebote der Feldforschung; LIT Verlag: Wien, Austria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, C.; Pregernig, M.; Fischer, C. Narrative und Diskurse in der Umweltpolitik: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen Ihrer Strategischen Nutzung; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M. Doing Discourse Analysis: Coalitions, Practices, Meaning. In Words Matter in Policy and Planning; van den Brink, M., Metze, T., Eds.; Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Takacs, D. The Idea of Biodiversity: Philosophies of Paradise; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schama, S. Landscape and Memory, 1st ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrand, E. Die Landschaft des Tourismus: Wie Landschaft von Reiseveranstaltern Inszeniert und von Touristen Konsumiert Wird, 1st ed.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Löfgren, O. On Holiday: A History of Vacationing, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt, L. Warum ist Landschaft schön? In Warum ist Landschaft Schön?: Die Spaziergangswissenschaft, 4th ed.; Burckhardt, L., Ritter, M., Schmitz, M., Eds.; Schmitz: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, J. The Yosemite: Chapter 16—Hetch Hetchy Valley. Available online: https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/writings/the_yosemite/chapter_16.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Spence, M.D. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, W. The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. Environ. Hist. 1996, 1, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ducarme, F.; Flipo, F.; Couvet, D. How the diversity of human concepts of nature affects conservation of biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibelriether, H. Fachtagung anlässlich des 11. In Ungestörte Natur—Was haben wir davon? Internationalen Wattenmeertages 1991 in Husum; Peter, P., Ed.; Umweltstiftung WWF Deutschland: Berlin, Germany, 1992; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- White, L. The Historical Roots of our Ecologic Crisis. Science 1967, 155, 1203–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aschenbrand, E.; Michler, T. Linking Socio-Scientific Landscape Research with the Ecosystem Services Approach to Analyze Conflicts About Protected Area Management—The Case of the Bavarian Forest National Park. In Modern Approaches to the Visualization of Landscapes; Edler, D., Kühne, O., Jenal, C., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Michler, T.; Aschenbrand, E.; Leibl, F. Gestört, aber grün. 30 Jahre Forschung zu Landschaftskonflikten im Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald. In Landschaftskonflikte, 1st ed.; Berr, K., Jenal, C., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Lima Action Plan for UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and its World Network of Biosphere Reserves (2016–2025). Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/SC/pdf/Lima_Action_Plan_en_final.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Batisse, M. Biosphere Reserves: A Challenge for Biodiversity Conservation & Regional Development. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 1997, 39, 6–33. [Google Scholar]

- Batisse, M. The Biosphere Reserve: A Tool for Environmental Conservation and Management. Environ. Conserv. 1982, 9, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgewater, P. The Man and Biosphere programme of UNESCO: Rambunctious child of the sixties, but was the promise fulfilled? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.F. People in biosphere reserves: An evolving concept. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1996, 9, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. What are Biosphere Reserves? Available online: https://en.unesco.org/node/314143 (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/biosphere (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Welp, M. Participatory and Integrated Management of Biosphere Reserves: Lessons from Case Studies and a Global Survey. GAIA—Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2008, 17, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. Aesthetic appreciation of landscape. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Howard, P., Thompson, I.H., Waterton, E., Atha, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgewater, P.; Rotherham, I.D. A critical perspective on the concept of biocultural diversity and its emerging role in nature and heritage conservation. People Nat. 2019, 1, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, D. Variations on the rural idyll. In Handbook of Rural Studies; Cloke, P., Mooney, P.H., Marsden, T., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Büttner, N. Geschichte der Landschaftsmalerei; Hirmer: München, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.G.; Price, M. Introducing UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. In UNESCO Biosphere Reserves: Supporting Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability and Society; Reed, M.G., Price, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Man and the Biosphere (MaB) Programme. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/mab/about (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Deutsche UNESCO-Komission. Biosphärenreservate. Available online: https://www.unesco.de/kultur-und-natur/biosphaerenreservate (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Frank, A.K. What is the story with sustainability? A narrative analysis of diverse and contested understandings. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2017, 7, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, G. Sustainable sufficiency—An internally consistent version of sustainability. Sust. Dev. 2005, 13, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. MAB Good Practices: Austria|austrian biosphere reserves|guidelines on the sustainable production of renewable energy in austrian biosphere reserves. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/mab/strategy/goodpractices (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Österreichisches Nationalkommitee MAB. Position Paper of the Austrian National Committee for the UNESCO Programme ‘Man and the Biosphere (MAB)’ for Using Renewable Energies in Austrian Biosphere Reserves. Available online: http://www.biosphaerenparks.at/images/pdf/Position-paper_Energy_english.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Weber, F.; Roßmeier, A.; Jenal, C.; Kühne, O. Landschaftswandel als Konflikt. In Landschaftsästhetik und Landschaftswandel; Kühne, O., Megerle, H., Weber, F., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 215–244. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin, R.M.; Witt, G.; Lacey, J. How wind became a four-letter word: Lessons for community engagement from a wind energy conflict in King Island, Australia. Energy Policy 2016, 98, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jessup, B. Plural and hybrid environmental values: A discourse analysis of the wind energy conflict in Australia and the United Kingdom. Environ. Politics 2010, 19, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colafranceschi, D.; Sala, P.; Manfredi, F. Nature of the Wind, the Culture of the Landscape: Toward an Energy Sustainability Project in Catalonia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Kühne, O.; Jenal, C.; Aschenbrand, E.; Artuković, A. Sand Im Getriebe: Aushandlungsprozesse Um Die Gewinnung Mineralischer Rohstoffe Aus Konflikttheoretischer Perspektive Nach Ralf Dahrendorf; Vieweg: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Costa, L.; Rybski, D.; Lucht, W.; Kropp, J.P. A Systematic Study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Interactions. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Büscher, B.; Fletcher, R. Towards Convivial Conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 17, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Cave, C.; Foley, K.; Bolger, T.; Hochstrasser, T. Urbanisation of Protected Areas within the European Union—An Analysis of UNESCO Biospheres and the Need for New Strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City 2015, 19, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. The ‘Urban Age’ in Question. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 731–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aschenbrand, E.; Michler, T. Why Do UNESCO Biosphere Reserves Get Less Recognition than National Parks? A Landscape Research Perspective on Protected Area Narratives in Germany. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413647

Aschenbrand E, Michler T. Why Do UNESCO Biosphere Reserves Get Less Recognition than National Parks? A Landscape Research Perspective on Protected Area Narratives in Germany. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413647

Chicago/Turabian StyleAschenbrand, Erik, and Thomas Michler. 2021. "Why Do UNESCO Biosphere Reserves Get Less Recognition than National Parks? A Landscape Research Perspective on Protected Area Narratives in Germany" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413647

APA StyleAschenbrand, E., & Michler, T. (2021). Why Do UNESCO Biosphere Reserves Get Less Recognition than National Parks? A Landscape Research Perspective on Protected Area Narratives in Germany. Sustainability, 13(24), 13647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413647