Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound effect on the system of education—gaps in students’ learning, their socioemotional and mental health problems and growing inequality have been recorded. These problems confront students from low socioeconomic status (SES) in particular, therefore supportive relationships with teachers are of great importance. The growth mindset, as a student’s belief that he or she can develop his or her capabilities, can help him or her cope with arising difficulties. Based on the first hypothesis, this study sought to establish whether teacher support is positively related to student’s achievement. Our second hypothesis is as follows: a student’s growth mindset moderates the positive effect of teacher support on students’ achievement; this relationship is stronger when the student’s growth mindset is higher. The research sample consisted of 163 students from municipalities of Lithuania that are regarded as socioeconomically disadvantaged. The research results show positive correlations between teacher’ support, student’s growth mindset and achievement. Additionally, the role of student’s growth mindset as a moderator between teacher support and the student’s achievement was established. Statistically significant differences between high-SES and low-SES students when comparing their growth mindsets and achievement prove that it is important to enhance confidence of low-SES students in their capabilities and the potential to develop them.

1. Introduction

In seeking to achieve the main goal of sustainable development, school communities have an important mission—to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all individuals and society, now and in the years to come [1]. This mission is reflected in the implementation of the fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4), that is, creating and ensuring qualitative and inclusive education for all children. It is with respect to sustainable development that one of the missions of a school is to contribute to promoting social justice and people’s wellbeing [2]. This can be achieved by creating positive teacher–student relationships, fulfilling socio-emotional needs of a child, and implementing individualised education that meets a child’s personal learning needs.

The COVID-19 pandemic had an enormous impact on the system of education all over the world. It led to a serious setback for the world’s ambition to achieve Sustainable Development Goals [3]. Research shows that the pandemic posed different challenges, such as gaps in student’s learning [4,5,6]; inequality [6,7] and socioemotional and mental health problems [7]. Learning loss more often was characteristic of low-SES students and schools [8]; the COVID-19 pandemic greatly aggravated adolescents’ symptoms of depression and anxiety and decreased their life satisfaction [9]. A lack of emotional connection and a perceived decrease in overall friend support [10] also affected the socioemotional wellbeing of students. Recent research has demonstrated that students need social awareness and emotional connectedness in order to study effectively [11].

It is obvious that the COVID-19 pandemic not only affected the organisation of teaching and learning processes, but it also influenced teacher–student relationships. As Niemi and Kousa [12] state, the main challenges posed to teachers included a non-authentic interaction and a lack of the spontaneity provided by in-person teaching. A sense of urgency and a fast pace of change influenced teachers’ work with students [13]; suddenly, teachers felt completely overwhelmed [14]. In the adolescents’ opinion, support provided by teachers, as well as communication with them, decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic [15].

There is no doubt that children learn best when a safe, stable school environment and healthy relationships are ensured, and when attention is devoted to socioemotional aspects of interaction in the learning process [16]. On the one hand, a supportive school environment and strong teacher–student relationships speed up the recovery from learning loss [17], and a sense of having positive relationships with others in a specific context is an important aspect of academic life [18]. On the other hand, research findings revealed that stronger perceived teacher support buffered against the negative outcomes associated with self-isolation [19]. Good relationships strengthen children’s psychological resilience; therefore, we think that it is necessary to direct undivided attention to interpersonal relationships at school and invest in their social and emotional development [20].

A growth mindset is an important feature characterising a student and relating to both an interaction with a teacher and the student’s achievement. The significance of growth mindset became especially pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic because people, with a higher growth mindset are more likely to thrive in the face of difficulty [21]. Students’ growth mindset plays an important role in the interaction between teacher support and the student’s achievement: the students with a higher growth mindset will have greater confidence, a better ability to cope with failure and uncertainty, and make greater efforts to overcome learning difficulties. There is some evidence suggesting that if a low-SES student has a growth mindset it works as a buffer against the negative effects of poverty on his achievement [22]. Hence, the current research is aimed at determining the role that a growth mindset plays in the relationship between teacher support (as a relationship variable) and a student’s achievement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Theoretical Background

Many scholars have analysed teacher–student relationships as an important factor in the learning process. These relationships have links with students’ functioning [23] and help slow or prevent declines in student motivation [24]. According to researchers, students with better developmental relationships with their teachers achieved better outcomes; these relationships strongly predicted academic motivation and a students’ sense of belonging to school community and school climate [25]. Positive relationships between teachers and students increase students’ engagement in the learning process [26] and help identify gaps in student’s learning at an earlier stage [27].

Researchers have also focused on the analysis of how a teacher–student relationship affects students’ achievement and vice versa—how students’ achievement influence relationships between teacher and student. A study by Ma, Liu, and Li [28] in mainland China adolescents shows that there is a positive correlation between a teacher–student relationship and students’ academic performance. Lee’s [29] investigation revealed that the teacher–student relationship was a meaningful predictor on students reading performance. Moreover, Xuan et al. [30] explored that the teacher–student relationship was a mediator between school SES and students’ math achievement. Furthermore, studies on teacher–student relationships with low SES students reveal another important aspect—not only that teacher–student relationships are one of the main vehicles through which teachers can positively affect their students [31], but teachers’ sense of meaning at work with their performance was mediated by teachers’ relationships with students [32].

Through recognising the significance of relationships to the learning process, it is clearly seen that their relevance increases in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [16]. With school communities suffering from instability, uncertainty, stress and anxiety, the stable environment of school and harmonious supportive relationships with adults become especially important to students. Creating the relationships, on the basis of which opportunities for students to become engaged in the learning process are created, is one of the most effective ways to overcome learning losses or avoid them [17]. Investigations show that such aspects of relationships as students’ perception of the teachers’ autonomy-supportive behaviour and student cohesiveness predict emotional engagement, while students’ perception of teachers’ autonomy-supportive behaviour and equity are important to behavioural engagement [33]. It is clear that learning as an interpersonal activity is closely linked to relationships. Investigations carried out during the pandemic show that students who learned by participating in face-to-face classes obviously learned more than the students who did online learning [17]. “Teaching and learning are always social and emotional practices, by design or neglect” [34] (p. 60), therefore, recovery from the pandemic must include a commitment to social emotional learning [16].

Along with the proposed programs for the development of social emotional skills and counselling on learning loss, we believe that during this period, teacher support for students should mean deeper listening to their needs (‘Lately you seem like you are not yourself. Is something going on? Maybe I can help?’) and more active collaboration with students’ parents. These could be invitations for informal conversations delving into changes in students’ behaviour.

Students from disadvantaged backgrounds (low SES) should receive special attention in cases such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Different countries have presented more and more evidence about the effect that teaching/learning conditions have on students’ learning outcomes. Investigations show a certain regularity: the learning outcomes of students from low SES are much worse compared with those of other students, and this difference seems to be increasing [35,36,37,38,39]. Furthermore, in the teachers’ opinion, online teaching/learning is absolutely ineffective at schools where many students from low-SES families learn [40]. According to Kaden [41], there is no single model for online learning that provides equitable educational opportunities for all. Therefore, online learning can increase educational inequality due to which students from a low-SES environment will experience learning losses and the risk of negative social, emotional, and behavioural consequences [42]. Research on home schooling also shows that it works well for students for whom intentional, personalized, and sufficient resources are available [43].

Previous research, e.g., [21,44,45], showed that student academic achievement depends not only on the student’s knowledge and abilities but also on how he or she is able to cope with failure and uncertainty. The effort made by the student when he or she encounters learning difficulties and obstacles and the way they respond to failure emotionally and the feeling they experience when a failure occurs, are also very important factors [46]. The growth mindset can be specified as the belief that students’ capacities are things you can develop through your efforts. Evidence, e.g., [47,48] show that growth mindset interventions have an enormous impact and are useful to students from a disadvantaged environment (low-SES). Bernardo [48] found that SES is a moderator between the student’s growth mindset and learning in mathematics and science in the nationwide Philippine sample.

The mediation and moderation analysis of relationships between growth mindset and achievement has attracted ever-growing attention from scholars. The majority of research into growth mindset, with few exceptions, e.g., [49], analyses of its effect on achievement and motivation [18,50]. For example, research carried out by Alvarado et al. [51] showed that there is a significant relationship between growth mindset, wellbeing, and performance. Furthermore, it was found that students’ wellbeing is a mediator between a growth mindset and performance [51]. Collie et al. [52] examined the role of growth goals in mediating the association between interpersonal relationships and academic outcomes.

It is noteworthy that developing teacher–student relationships is a significant factor in learning and achievement of low-SES students. On the basis of the Expectancy-Value Theory [53,54], the link between teacher–student relationships and the academic achievement of students can be theoretically substantiated. As researchers [30] underline, students who have a positive relationship with teachers are more likely to have positive expectancies and values for success. The teacher–student relationship can thus influence students’ expectations and the evaluation of school performance, as well as students’ academic success. Additionally, the Self-Determination Theory [55] can explain links between relationships, growth mindset, and achievement. Relatedness is one of three basic needs of the student (alongside competence and autonomy) and its satisfaction in the learning process influences the student’s intrinsic motivation, and at the same time deep learning and higher achievement. It is likely that the growth mindset is closely related to the student’s needs—competence when confidence in his or her abilities strengthens the aspiration to feel efficient in learning.

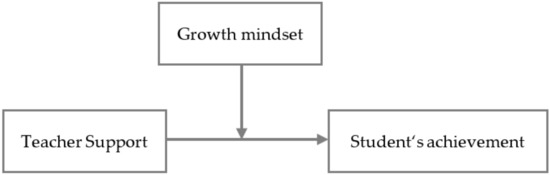

To summarise, we intend to emphasise that a teacher’s support of students during the learning process is key in cases such as the COVID-19 pandemic for all students, particularly in the group of more vulnerable students, such as low-SES ones. Therefore, we put forward the hypothesis that teacher support is positively related to student’s achievement. Students’ growth mindset plays a significant role in the intercorrelation of these variables: the student who holds a higher growth mindset will have more confidence in his or her capabilities, will more easily cope with failure and uncertainty, and will devote more effort to overcome learning difficulties. Hence, our second hypothesis is as follows: the student’s growth mindset moderates the positive effect of the teacher’s support on students’ achievement, such that this relationship is stronger when students’ growth mindset is higher. Since studies have proved that differences in sociodemographic variables (such as gender, belonging to low SES) can affect the student’s achievement and growth mindset, in our research we should take these variables into consideration when verifying the second hypothesis. Based on the above analysis, we provide a theoretical model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of growth mindset.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

Convenience sampling was used for selecting participants.

Our research targets were schools from municipalities of Lithuania with low SES contexts. Based on a 2019 Overview of the Lithuanian Educational System [56], we selected schools from these municipalities which were classified as schools with unfavourable SES contexts, where a large number of students from low-income households’ study. As the questions related to low SES are sensitive issues due to their vulnerable sample of respondents, not all schools agreed to participate in the research.

Four secondary education schools from three municipalities of Lithuania with low SES contexts agreed to participate in this research. These schools are small and located in small towns or rural areas, representing the characteristics of communities working effectively in the context of low SES. The communities of these schools address the problem of students’ low academic achievements and have accomplished significant improvement over two years.

All 7th–10th grade students, a total of 314 students of the afore mentioned schools, were invited to volunteer in the study. As many as 201 students (64%) filled in the questionnaire. Answers of 163 students, who completed the full questionnaire, are analysed in the present article. The research sample included 46% males and 54% females. 38% of the participants were low-SES students (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of research sample.

3.2. Data Collection Instruments

The questionnaire was divided into three parts. The first part of the questionnaire consists of the subscale Teacher support from the questionnaire What Is Happening in this Class? (WIHIC) [57,58,59]. From this scale the students’ perception of teacher support is assessed, that is, the extent to which a teacher helps them, takes interest in them, and maintains friendly relations with them is calculated. The subscale comprised eight items (the sample item “The teacher considers my feelings”). The items were scored on a five-point frequency scale with the alternatives of almost never (1), seldom (2), sometimes (3), often (4), and almost always (5) to indicate the degree of agreement with each statement. Cronbach’s alpha value (α = 0.930) suggests that the Teacher support subscale has an acceptable internal consistency.

The Growth mindset questionnaire containing eight statements drawn up by Agne Brandisauskiene is presented in the second part of the questionnaire. Examples of the statements are as follows: ‘No matter what my capabilities are, I can always change them a little’, ‘I have certain capabilities and I cannot change them’. Answers to each statement are presented on the 5-point Likert scale, where 1 means Strongly disagree and 5 means Strongly agree. The higher the overall average of the statements, the stronger the student’s belief in the possibilities to develop his/her capabilities is. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient shows that internal consistency of the scale is sufficient (0.675).

Such socio-demographic variables as gender, grade and socioeconomic status were collected in the third part of the questionnaire. The students who were from low-income families, that is, who received social assistance (free meals at school) were attributed to the category of students from the low SES background. Student’s achievement was analysed using the grades received in the native language (the Lithuanian language) and mathematics. On their basis, the annual average of these grades was calculated, which is used in the statistical analysis of research data.

3.3. Procedure and Ethics

Information about the study was first distributed among school principals and their permission was obtained. All the students participated voluntarily in the investigation and were free to fill in the data set. Their confidentiality was guaranteed. Written consents from students’ parents allowing their children to participate in the study were obtained. Data was collected in May 2021. The participants in the investigation completed a self-report questionnaire on the online platform https://apklausa.lt/ (accessed on 22 May 2021). Students filled in the questionnaire at home, at the time convenient for them; in this way, neither researchers nor teachers could exert any influence on the answers. The study procedures were carried in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Research Ethics Committee of the Education Academy of Vytautas Magnus University approved this study (protocol number SA-EK-21-03). Permission to use the questionnaire What Is Happening in this Class? was obtained by the first author of the present article.

3.4. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 was used to calculate descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, percent). Normality of the variables was checked with skewness, and kurtosis. All variables were normally distributed, when skewness and kurtosis values were between −1 and +1 [60]. Independent samples t-test was used to test differences in gender and grade, as well as differences between low and high SES students. To compare these differences, standardised effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated. For Cohen’s d, a value of 0.20 was interpreted as a weak effect, 0.21–0.50—as a modest effect, 0.51–1.00—as a moderate effect, and >1.00—as a strong effect [60]. Pearson correlation analysis was carried out to investigate the possible relationship between students’ perceptions of teacher support, student’s growth mindset and student’s achievement. The following values of the coefficient are suggested to be followed to interpret the strength of the relationship between a correlation between two variables: a correlation of <0.19 is considered very weak, 0.20–0.39—weak, 0.40–0.59—moderate, 0.60–0.79—strong, >0.80—very strong (for positive, as well as negative values) [60]. Multiple regression analysis was used to determine the moderating effect of growth mindset.

Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaires. The alpha value between 0.60 and 0.95 was considered acceptable [60]. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all tests.

4. Results

Research data analysis indicated that all variables were approximately normally distributed and there were no extreme outliers (Table 2). When analysing the results, a rather low average score of the students in our research sample should be taken into consideration. The highest score of students at schools in Lithuania is 10, and the lowest one is 4. Hence, the annual average score of 6.21 (Table 2) obtained in our research sample is lower than the annual average score of the student who receives medium positive evaluations.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

The average of the estimates of perceived teacher support in the overall sample totals 3.32 (Table 2), and it ranges between 3.29 and 3.36 in the groups of students differing in sociodemographic characteristics, which is higher than a possible theoretical scale average of 3. It should be noted, however, that the distribution of research estimates in this scale is quite large (from 1.13 to 5).

The average of the estimates of the third variable, the growth mindset, is 2.88 in the overall research sample (Table 2), and in the groups of students differing in sociodemographic characteristics ranges between 2.78 and 2.94 (Table 3). Attention should be drawn to the fact that though the highest possible estimate on this scale is 5, the highest estimate in the present research sample totalled 3.75 (the lowest one was 1.75; Table 2)—the students who participated in the study did not have a high level of belief and confidence in the opportunities to improve their capabilities. This information is important in order to understand the context of phenomenon correlation analysis presented below.

Table 3.

Independent samples t-test results depending on gender, grade, and SES background.

Table 3 presents results of independent samples t-test. When analysing the results of the study, we see that both girls and boys experience teacher support in the same way, and the perception of teacher support does not differ depending on the grade and the SES background.

Students’ growth mindset differs in the groups of low-SES (M = 2.78, SD = 0.41) and high-SES (M = 2.94, SD = 0.41) students: a lower growth mindset is more characteristic of the low-SES group of students (t = −2.437, p < 0.05). The effect size of this difference was medium (Cohen’s d = 0.41). When considering growth mindset by gender and grade, no statistically significant differences were noticed.

When analysing students’ achievement data, statistically significant differences were noticed in the student groups of different gender and the SES background. Lower achievements are characteristic of low-SES students (M = 5.32, SD = 0.66) as compared with those of their schoolfellows (M = 6.76, SD = 1.81; t = −5.28, p < 0.001). The effect size of this difference was strong (Cohen’s d = 1.74). Girls learned statistically significantly better than boys (t = −2.457, p < 0.05), their annual average score is 6.54, whereas that of boys is 5.83. The effect size of this difference was strong (Cohen’s d = 1.85).

Seeking to elucidate the correlation between teacher support, growth mindset and student’s achievement, the Pearson correlation coefficients r was calculated. Table 4 shows that a statistically significant correlation between all three research variables was established. However, significant positive correlations between teacher support and growth mindset (r = 0.177, p < 0.01) and between teacher support and students’ achievement (r = 0.183, p < 0.01) show that association is very weak. The significant positive correlations between students’ achievement and growth mindset (r = 0.362, p < 0.01) is weak.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficient between variables.

Seeking to find out if the interrelation between teacher support and student’s achievement is influenced by other variables able to distort it, the partial correlation was calculated. Having eliminated the impact of two variable (gender and SES background), it became clear that the link relating teacher support and student’s achievement strengthened, i.e., increased from r = 0.183 to r = 0.214 (significant positive weak correlation, p = 0.006). This means that the first hypothesis is confirmed—the stronger students experience teacher support, the higher their achievement.

Data presented in Table 4 show that growth mindset and student’s achievement are related by a statistically significant link (r = 0.362, p < 0.001). Therefore, a further analysis of research data is sought to elucidate if the growth mindset could be a moderator between independent (teacher support) and dependent (student’s achievement) variables and strengthen the correlation between them. To test the moderating effects, multiple regressions analysis was used. Two regression models were estimated. In Model 1, student’s achievement was regressed on the centred scores of growth mindset, teacher support and the interaction between growth mindset and teacher support. Model 2 was identical to Model 1, except that the variables of gender and SES were additionally controlled. If a significant interaction was found, then a simple slope analysis was conducted to determine whether teacher support is associated with student’s achievement at high and low levels of growth mindset as a moderator.

The results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 5. The predictors in Model 1 accounted for 16.1% of the variance in student’s achievement (F = 11.389; p < 0.001). Both growth mindset and teacher support were significantly positively associated with student’s achievement. Moreover, the interaction between the variables of growth mindset and teacher support was significant. The simple slope analysis showed that a positive relationship between teacher support and student’s achievement was significant at higher levels of the moderator (b = 0.590, p < 0.01), whereas at the lower levels of a moderator the interaction between aforementioned variables was not significant (b = −0.010, p > 0.05).

Table 5.

The results of the regression analysis.

The predictors in Model 2 accounted for 25.9% of the variance in student’s achievement (F = 12.346; p < 0.001). The effects of growth mindset and teacher support, as well as their interaction, remained significant in Model 2. The simple slope analysis showed the results very similar to those mentioned previously. A positive relationship between teacher support and student’s achievement was significant at higher levels of the moderator (b = 0.571, p < 0.01) and was not significant at its lower levels (b = 0.077, p > 0.05).

In summary, we see that a higher growth mindset as a moderator strengthens the connection between teacher’s support and student’s achievement, although the effect is not very strong.

5. Discussion

With the pandemic sweeping the country, school communities are looking for answers to the questions about how to deal with the challenges directly related not only to the learning process (that is, forms of teaching, achievement) but also to the students’ wellbeing, particularly having in the mind such vulnerable students as those from low SES. It is obvious that in this respect, one of the research variables—teacher support—does not lose its relevance. The first hypothesis confirmed by our investigation reveals that there exists a positive relationship between teacher support and student’s achievement. The research results obtained lead to the conclusion that teacher–student relationships can be conducive to student’s effective learning. These research results conform with the research results obtained by other scholars and suggest that better teacher–student interrelations determine better student learning outcomes [24,25]. Attention should be drawn to the fact that in assessing the teacher support variable, no statistically significant differences, either in gender, grade or student SES, were noticed. This data suggests that a supportive school environment in which possibilities are created for students to become engaged in the learning process and have better learning outcomes, is being created at schools under investigation.

Though the importance of teacher–student relationships to student’s achievement has been studied, researchers are still looking for an answer to the question about what external or internal factors participate in this interaction. One of the assumptions is that a student’s growth mindset can be a significant variable in the interaction between teacher support provided to a student (constituent of relationships) and the student’s achievement: a student who feels a stronger belief in the possibilities of developing his/her capabilities will put more effort into learning, will look for help from his/her teacher more actively, which means that he/she will cope with difficulties and challenges easier. Therefore, we put forward a second research hypothesis suggesting that the growth mindset moderates the positive effect of teacher support on the student’s achievement, and this hypothesis was not confirmed. Analysis of results showed that a positive relationship between teacher support and student’s achievement is stronger when the student’s growth mindset is higher. This means that when a student believes that he/she can develop his/her capabilities this reinforces the importance of teacher’s support for his/her achievement. Students with a high growth mindset are more likely to take advantage of teacher’s support than other students.

Seeking to understand the interaction between these phenomena, we think it is very important to pay attention to the fact that statistically significant differences between the growth mindset and students’ SES were noticed in our investigation. Research results show that lower levels of the growth mindset (a lack of belief in the development of one’s capabilities) are characteristic of the overall research sample. However, when analysing the results of low-SES students, it becomes apparent that those students have even less confidence in the development of their capabilities and feel as though their efforts have no meaning. These research results are also confirmed by other scholars. For example, Destin et al. [61] indicate that students from low SES tend to have a lower mindset (fixed mindset) than those who are from high SES backgrounds. SES might guide the development of student’s broader fixed or growth mindsets in systematic ways with consequences for academic outcomes [61]. When comparing the impact of gender as a variable on the student’s growth mindset, ambiguous results were obtained in other scientific research studies. Research carried out by Gandhi et al. [18] shows that a student’s gender and race had no effect on low-income student’s academic performance. Meanwhile, a study by Alvarado et al. [51] shows an indirect gender effect, ‘the mediation of wellbeing occurs only for females and not for males; this mediation may in turn be influenced by a growth versus fixed mindset’ (p. 854). We tend to support the hypothetical assumption that a growth mindset can be more characteristic of girls as different studies show that, with respect to gender, girls are more likely to concentrate, focus on learning and put more effort into it than males [33]; however, this assumption was not confirmed—gender is not a significant variable in our sample, which has an impact on the student’s growth mindset. Still, it is important to emphasise that the trust in adults and the fairness of the environment may be important precursors to a growth mindset [49]. On the other hand, teachers’ mindsets about student’s intelligence are also of great importance because, according to scholars [62], teachers with fixed views of a student’s ability might tend to assume less responsibility for their students’ academic achievement.

Finally, we would like to emphasise specific conditions in which the research was carried out—the COVID-19 context. Hypothetically, we can safely say that this unusual long-lasting pandemic period characterised by uncertainty and a lack of social relations, might have partly determined such moderation results obtained. Maybe, hypothetically, the relationship with their teachers, that is, satisfying socioemotional needs, was more important for the students holding a lower growth mindset who took part in the investigation than their academic achievement. We think that investigations should be carried on trying to elucidate the theoretically formulated relationship between teacher support and student’s achievement, which can be moderated by the student’s growth mindset.

6. Limitations, Future Research Directions and Practical Implementation

Our study was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a small and specific sample (schools of low SES context) of research subjects, and as cross-sectional research. We recognise this as a limitation for the generalisation of our research results and think that it is reasonable to continue investigations broadening the research sample and carrying it out as a longitudinal. A further research direction could be related to different aspects of the teacher–student relationship (students’ perception of teachers’ autonomy-supportive behaviour, social equity), interrelations between students’ cooperation, students’ cohesiveness, students’ engagement, and teacher’s attitudes toward students’ capacities.

In discussing the aspects of the practical implementation of the current investigation, some of them should be emphasised. First, the investigation confirmed that teacher support is related to student’s achievement, and greater support increases the achievement. Therefore, it is very important that teachers, seeking to establish a close emotional relationship with students in the learning process, should show signs to students that the latter are accepted and needed (‘I am happy that you are at my lesson today’, ‘It is very important to me that you should learn it’, and so on). Additionally, teachers should pay attention to the way they address the students. Students first hear the word with its emotional content without thinking about its meaning. In this case, such short utterances of a teacher as ‘you failed, you did not do it, you never do your homework’ might make a student feel that he/she is ‘a loser’, ‘incapable of anything’ and drive him/her to grievance, disappointment, or reluctance to learn. An emotionally favourable relation with a student must be created at the beginning of the learning process and continue throughout it.

Second, the established tendency for students under study to have a lower growth mindset encourages teachers to look for ways of helping them to start believing that their capabilities can be developed making efforts and at the same time to show that the teacher is not indifferent to the student’s capacity building and development. In this case, the teacher’s interest in the student’s performance and the assessment of the latter’s efforts are very important (‘You really worked hard, and I see that you were able to do it…’). This development of the student’s capabilities can be planned step by step, which would ensure the success of learning, encourage the student’s self-activity (I am able) and strengthen his/her intrinsic motivation to learn. Low SES students have stronger motivation to learn at school when conditions are created for them to see that their efforts were crowned with success [63]. It is noteworthy that the student’s growth mindset is related to teachers’ attitudes towards students too. If the teacher treats the students as being able to develop their capabilities and acknowledges the meaning of their efforts, they would be more inclined to rely on pedagogy which gives high priority to the learning process. In this case, the teacher will strive to individualise the student’s learning in the learning process and enhance the student’s persistence to pursue excellence. This can create preconditions for the development of student’s growth mindset. According to Schmidt et al. [64], teachers play a special role in initiating interventions related to the development of student’s growth mindset.

In summary, it can be stated that it is very important to invest in fostering the growth mindset of low-SES students. On the other hand, we subscribe to the opinion of the scholars who state that the growth mindset itself ‘may not be the mechanism of change, but it may spur important goal-monitoring and self-regulatory processes, that then shape a more successful outcome’ [49], p. 511.

7. Conclusions

Seeking to achieve the objective set—to determine the significance of the growth mindset to the relationship between teacher support (as a variable of relationship) and student’s achievement during the COVID-19 pandemic—unequivocal results encouraging further investigations to be carried out in this research field have been obtained.

In analysing research variables by sociodemographic characteristics, the greatest differences were noticed in the analysis of the achievement results: student’s achievement differed statistically significantly by gender (girls’ performance was better than that of boys) and by the SES background (achievement of low-SES students were considerably lower than those of their schoolfellows). In assessing the level of the growth mindset, significant differences by the SES background were also revealed (a lower growth mindset as compared to that of other students is a characteristic of low-SES students), however, no differences by gender were noticed. When analysing the achievement and growth mindset results, no significant differences in different grades were determined. Perception of teacher support did not differ significantly, either by gender, grade, or the SES background.

The research results show that the first hypothesis has been confirmed: the more support the students receive from teachers, the higher their achievements are. The second hypothesis, which states that a student’s growth mindset moderates the positive relationship between teacher support and student’s achievement was also confirmed: the relationship between teacher support and student’s achievement is stronger when the student’s growth mindset is higher. However, it is noteworthy that the interaction between aforementioned variables was not significant at the lower levels of a moderator (the growth mindset variable).

To sum up, it is obvious that the growth mindset is a feature separating low-SES students from others; however, further investigations are needed to ascertain the importance of the growth mindset in the interaction between teacher–student relationships and student’s achievement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., J.C., A.D., E.K.-I., L.B.-M. and R.N.-M.; writing—A.B., L.B.-M. and R.N.-M.; data collecting J.C. and E.K.-I.; data analysis, interpretation of the results J.C., A.D. and E.K.-I.; review and editing, A.B., A.D., E.K.-I. and L.B.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) project “Creating a Supportive Learning Environment: in Search of Factors enabling the School Com-munity” (Agreement No. S-DNR-20-1), co-financed by the European Union under the measure “Implementation of Analysis and Diagnostics of Short-term (Necessary) Research (in Health, Social and Other Fields) related to COVID-19”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Education Academy Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania (Protocol number: SA-EK-21-03).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Scott, W. New Worlds Rising? The View from the Sustainable School. Policy Futures Educ. 2010, 8, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19. Sustainable Development Report 2020; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Available online: https://sdgindex.org/reports/sustainable-development-report-2020/ (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Dorn, E.; Hancock, B.; Sarakatsannis, J.; Viruleg, E. COVID-19 and Learning Loss—Disparities Grow and Students Need Help. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-learning-loss-disparities-grow-and-students-need-help (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Kuhfeld, M.; Soland, J.; Tarasawa, B.; Johnson, A.; Ruzek, E.; Liu, J. Projecting the Potential Impact of COVID-19 School Closures on Academic Achievement. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskó, Z.; da Costa, P.; Schnepf, S.V. Learning Loss and Educational Inequalities in Europe: Mapping the Potential Consequences of the COVID-19 Crisis. IZA Discussion Papers 14298. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA). 2021. Available online: https://ftp.iza.org/dp14298.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2021. OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engzell, P.; Frey, A.; Verhagen, M.D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022376118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.A.; Ha, T.; Ockey, S. Adolescents’ Perceived Socio-Emotional Impact of COVID-19 and Implications for Mental Health: Results from a U.S.-Based Mixed-Methods Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Martinsone, B.; Tali, S. Promoting Sustainable Social Emotional Learning at School through Relationship-Centered Learning Environment, Teaching Methods and Formative Assessment. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2020, 22, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, H.M.; Kousa, P. A case study of students’ and teachers’ perceptions in a Finnish high school during the COVID pandemic. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 2020, 4, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, C.; Mercieca, D.; Mercieca, D. What can I do? Teachers, students and families in relationship during COVID-19 lockdown in Scotland. Malta Rev. Educ. Res. 2020, 14, 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, R.; Lewis, K. Building Partnerships to Support Teachers with Distance Learning During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Cohorts, Confidence, and Micro-teaching. Issues Teach. Educ. 2020, 29, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lessard, L.M.; Puhl, R.M. Adolescent academic worries amid COVID-19 and perspectives on pandemic-related changes in teacher and peer relations. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. What the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Taught Us about Teachers and Teaching. In Children and Schools during COVID-19 and Beyond: Engagement and Connection through Opportunity; Royal Society of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; pp. 138–167. Available online: https://rsc-src.ca/sites/default/files/C%26S%20PB_EN_0.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Webinar. Strategies and Solutions for Mitigating COVID-19 Learning Loss (27 August 2020). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. Available online: https://annenberg.brown.edu/events/strategies-and-solutions-mitigating-covid-19-learning-loss (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Gandhi, J.; Watts, T.W.; Masucci, M.D.; Raver, C.C. The Effects of Two Mindset Interventions on Low-Income Students’ Academic and Psychological Outcomes. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2020, 13, 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.F.; Wachs, S. Self-Isolation During the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Adolescents’ Health Outcomes: The Moderating Effect of Perceived Teacher Support. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, H.; Dadvand, B. Social and emotional learning and resilience education. In Health and Education Interdependence; Midford, R., Nutton, G., Hyndman, B., Silburn, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. What Can Be Learned from Growth Mindset Controversies? Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, S.; Pauneskub, D.; Dweck, C.S. Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8664–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duong, M.T.; Pullmann, M.D.; Buntain-Ricklefs, J.; Lee, K.; Benjamin, K.S.; Nguyen, L.; Cook, C.R. Brief teacher training improves student behavior and student-teacher relationships in middle school. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, P.C.; Pekel, K.; Sethi, J.; Chamberlain, R.; van Boekel, M. Academic Year Changes in Student-Teacher Developmental Relationships and Their Linkage to Middle and High School Students’ Motivation: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Early Adolesc. 2020, 40, 499–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, P.C.; van Boekel, M.; Pekel, K.; Syvertsen, A.K.; Roehlkepartain, E.C. Effects of developmental relationships with teachers on middle-school students’ motivation and performance. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 646–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J. Teacher-Student Relationships and Students’ Engagement in High School: Does the Number of Negative and Positive Relationships with Teachers Matter? J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allensworth, E.; Schwartz, N. School Practices to Address Student Learning Loss. Brief No. 1. 2020. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED607662 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Li, B. The association between teacher-student relationship and academic achievement: The moderating effect of parental involvement. Psychol. Sch. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S. The Effects of the Teacher-Student Relationship and Academic Press on Student Engagement and Academic Performance. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 53, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xuan, X.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, C.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, W.; Qi, M.; Wang, Y. Relationship among school socioeconomic status, teacher-student relationship, and middle school students’ academic achievement in China: Using the multilevel mediation model. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavy, S.; Bocker, S. A path to teacher happiness? A sense of meaning affects teacher-student relationships, which affect job satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1439–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S.; Ayuob, W. Teachers’ Sense of Meaning Associations with Teacher Performance and Graduates’ Resilience: A Study of Schools Serving Students of Low Socio-Economic Status. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandisauskiene, A.; Buksnyte-Marmiene, L.; Cesnaviciene, J.; Daugirdiene, A.; Kemeryte-Ivanauskiene, E.; Nedzinskaite-Maciuniene, R. Sustainable School Environment as a Landscape for Secondary School Students’ Engagement in Learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity; Teachers College Press, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Domingue, B.W.; Hough, H.J.; Lang, D.; Yeatman, J. Changing Patterns of Growth in Oral Reading Fluency during the COVID-19 Pandemic [Policy Brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. 2021. Available online: https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/changing-patterns-growth-oral-reading-fluency-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Kogan, V.; Lavertu, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Student Achievement on Ohio’s Third-Grade English Language Arts Assessment. Ohio State University, John Glenn College of Public Affairs. 2021. Available online: https://glenn.osu.edu/sites/default/files/2021-09/ODE_ThirdGradeELA_KL_1-27-2021.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Kogan, V.; Lavertu, S. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Student Learning in Ohio: Analysis of Spring 2021 Ohio State Tests. Ohio State University, John Glenn College of Public Affairs. 2021. Available online: https://glenn.osu.edu/sites/default/files/2021-10/210828_KL_OST_Final_0.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Maldonado, J.; De Witte, K. The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pier, L.; Christian, M.; Tymeson, H.; Meyer, R.H. COVID-19 Impacts on Student Learning: Evidence from Interim Assessments in California [Report]. Policy Analysis for California Education. 2021. Available online: https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/covid-19-impacts-student-learning (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Chen, L.-K.; Dorn, E.; Sarakatsannis, J.; Wiesinger, A. Teacher Survey: Learning Loss Is Global—And Significant. Public & Social Sector Practice. McKinsey & Company. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/teacher-survey-learning-loss-is-global-and-significant (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Kaden, U. COVID-19 School Closure-Related Changes to the Professional Life of a K–12 Teacher. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drane, C.; Vernon, L.; O’Shea, S. The impact of ‘learning at home’ on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Literature Review prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education; Curtin University: Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, E.; Weiss, E. COVID-19 and Student Performance, Equity, and U.S. Education Policy. Lessons from Pre-Pandemic Research to Inform Relief, Recovery, and Rebuilding. Econ. Policy Inst. 2020. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED610971 (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Blackwell, L.S.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Dweck, C.S. Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 47, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Essays in social psychology. In Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development; Psychology Press, Taylor and Francis Group: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sisk, V.F.; Burgoyne, A.P.; Sun, J.; Butler, J.L.; Macnamara, B.N. To What Extent and under Which Circumstances Are Growth Mind-Sets Important to Academic Achievement? Two Meta-Analyses. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, A.B.I. Socioeconomic status moderates the relationship between growth mindset and learning in mathematics and science: Evidence from PISA 2018 Philippine data. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 9, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.J.; de Cunha, M.J.; de Souza, D.A.; Santo, J. Fairness, trust, and school climate as foundational to growth mindset: A study among Brazilian children and adolescents. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, S. Growth mindset and motivation: A study into secondary school science learning. Res. Pap. Educ. 2017, 32, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, N.B.O.; Rodríguez Ontiveros, M.; Ayala Gaytán, E.A. Do Mindsets Shape Students’ Well-Being and Performance? J. Psychol. 2019, 153, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collie, R.J.; Martin, A.J.; Papworth, B.; Ginns, P. Students’ interpersonal relationships, personal best (PB) goals, and academic engagement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 45, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Expectancy-Value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigfield, A.; Gladstone, J.R. What does expectancy-value theory have to say about motivation and achievement in times of change and uncertainty? In Advances in Motivation and Achievement (Motivation in Education at a Time of Global Change); Gonida, E.N., Lemos, M.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; Volume 20, pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lietuva. Švietimas Šalyje Ir Regionuose 2019. Mokinių Pasiekimų Atotrūkis [Lithuania. Education in the Country and Regions 2019. Students’ Achievement Gap]. Available online: https://www.smm.lt/uploads/documents/tyrimai_ir_analizes/2019/B%C5%ABkl%C4%97s%20ap%C5%BEvalga%202019_GALUTINIS.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Fraser, B.J.; Fisher, D.L. Development and validation of short forms of some instruments measuring student perceptions of actual and preferred classroom learning environment. Sci. Educ. 1983, 67, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B.J.; McRobbie, C.J.; Fisher, D.L. Development, validation and use of personal and class forms of a new classroom environment instrument. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York, NY, USA, 8–12 April 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge, J.M.; Fraser, B.J.; Huang, I.T.-C. Investigating classroom environments in Taiwan and Australia with multiple research methods. J. Educ. Res. 1999, 93, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Destin, M.; Hanselman, P.; Buontempo, J.; Tipton, E.; Yeager, D.S. Do Student Mindsets Differ by Socioeconomic Status and Explain Disparities in Academic Achievement in the United States? AERA Open 2019, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.; Kravchenko, N.; Chen-Bouck, L.; Kelley, J.A. General and domain specific beliefs about intelligence, ability, and effort among preservice and practicing teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 59, 180–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browman, A.S.; Destin, M.; Carswell, K.L.; Svoboda, R.C. Perceptions of socioeconomic mobility influence academic persistence among low socioeconomic status students. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 72, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, J.A.; Shumow, L.; Kackar-Cam, H. Exploring teacher effects for mindset intervention outcomes in seventh-grade science classes. Middle Grades Res. J. 2015, 10, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).