David against Goliath: Diagnosis and Strategies for a Niche Sport to Develop a Sustainable Fan Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Global Sport vs. Traditional Sport

1.2. The Battle for the World’s Attention in the Era of Sport as Spectacle

1.3. Fan Communities in Niche Sports

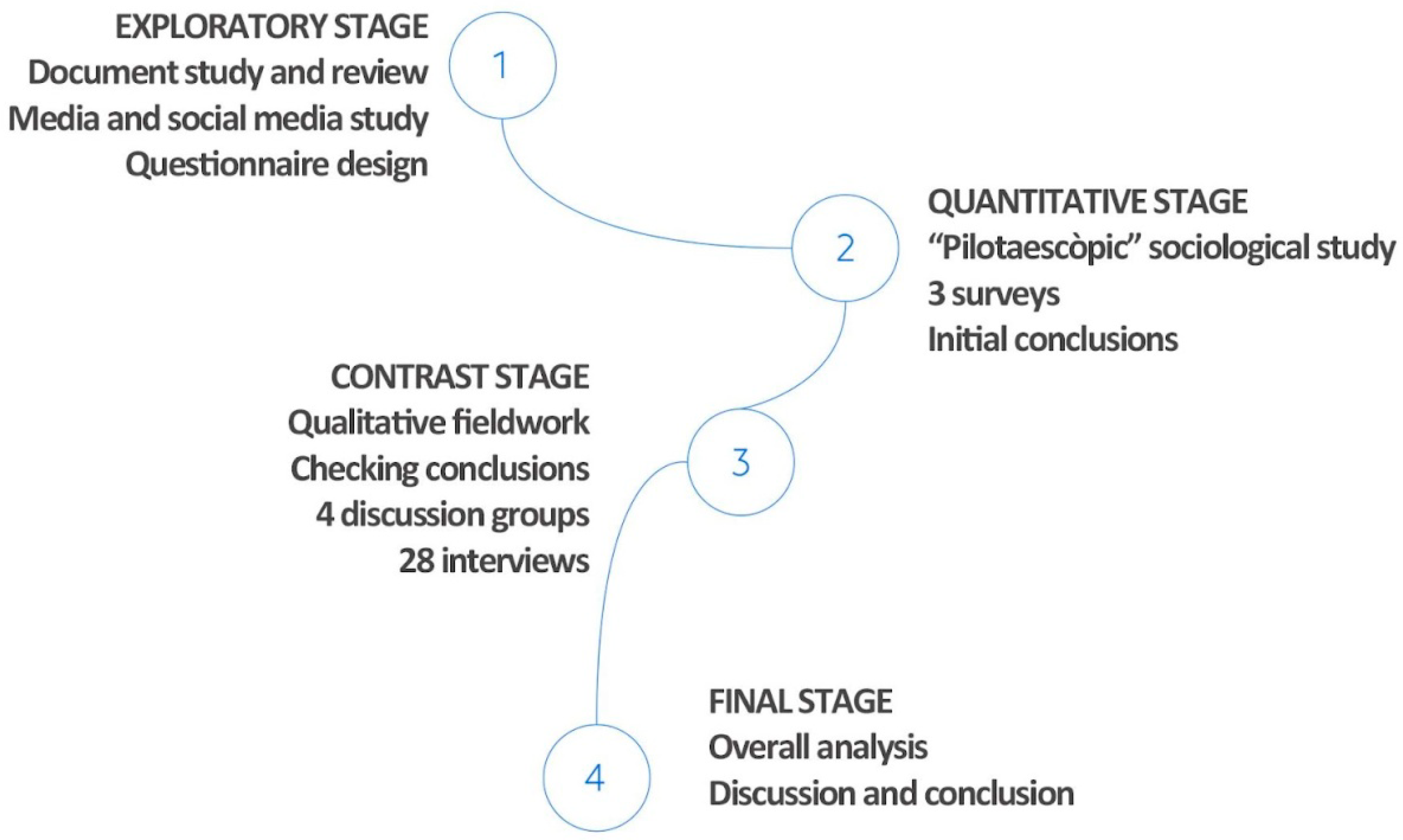

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Document Study

- Media notoriety.

- The audience figures for television broadcasts.

- Social media followers of institutional profiles or professional players.

2.2. Quantitative Stage

- The general population—all residents of the Valencian Country, consisting of 5,057,353 inhabitants, according to the last census by the Spanish National Statistical Institute.

- Fans of Valencian pilota—all the people who spend leisure time enjoying playing or watching this local sport.

- The 1596 players aged over 16 who hold a federation licence.

2.3. Comparison Stage

2.4. Final Stage

3. Results

3.1. Notoriety, Audiences and Coverage in Traditional Sports Networks

- During 2019, there were 55 broadcasts of Valencian pilota.

- 40 of these showed professional matches and 17 amateur games (30% of the total), while five women’s matches—8.5% of the 57—were televised.

- The average audience for Valencian pilota broadcasts is 12,000 spectators per programme, with an audience share of 1.6%.

- The five broadcasts with the biggest audiences—over 25,000 viewers—showed professional matches.

- The most-seen match obtained a peak of 49,000 viewers. The second most popular broadcast had 32,000 viewers.

3.2. Quantitative Results

3.2.1. Knowledge of Valencian Pilota among the General Population

3.2.2. Transmission Routes for Pilota and Media Consumption

3.2.3. The Consumer Experience at Live Sports Events

3.3. Qualitative Results

3.3.1. Checking the Data Presented

Concerning Knowledge

On the Transmission and Media Coverage of the Traditional Sport

3.3.2. Innovative Proposals in the Governance and Communication and Marketing Strategy for Traditional Sport

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationship between Results and Background Research

4.2. Theoretical Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

5.1. Review of Research Questions

5.2. Management Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez López, J. Historia del Deporte; Inde Producciones: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Diem, C. Historia de los Deportes; Luis de Caralt: Barcelona, Spain, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Millo, L. El Trinquet; Prometeo: Valencia, Spain, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Agulló, R.; Agulló, V. El Joc de Pilota a Través de la Prensa Valenciana 1790–1909; Valencia Provincial Council: Valencia, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- García Frasquet, G.; LlopisBauset, F. Vocabulari del Joc de Pilota; Department of Culture, Education and Science, Valencian Regional Government: Valencia, Spain, 1991.

- Agulló, V.; Castillo, B. El joc de pilota. l’esport rei dels valencians. Rev. Valenc. d’Estud. Auton. 2013, 2, 72–95. [Google Scholar]

- González Ramallal, M. Sociedad y Deporte: Análisis del Deporteen la Sociedad y su Reflejoen los Medios de Comunicación en España. Ph.D. Thesis, University of La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N.; Dunning, E. Deporte y Ocio en el Proceso de Civilización; FCE: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero Herráiz, A. El deporte en el proceso de civilización. La teoría de Norbert Elias y su aplicación a los orígenes deportivos en España. Citius Altius Fort. 2015, 8, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- De Luze, A. La Magnifique Histoire du Jeu de Paume; Bossard: Paris, France, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Mastromartino, B.; Qian, T.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, J.J. Developing a Fanbase in Niche Sport Markets: An Examination of NHL Fandom and Social Sustainability in the Sunbelt. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moragas Spà, M. Comunicación y Deporte en la Era Digital. In Proceedings of the Congress of the Spanish Association for Social Research Applied to Sport (AEISAD); Centre d’Estudis Olímpics, UAB: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2007; Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/13282886.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Robertson, R. Mapping the Global Condition: Globalization as the Central Concept. Theory Cult. Soc. 1990, 7, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulianotti, R. Sports Spectators and the Social Consequences of Commodifications: Critical Perspectives from Scottish Football. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2005, 29, 386–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maguire, J. Global Sport: Identities, Societies, Civilizations; Wiley: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, A.; Jackson, S.J. Sports Marketing and the Challenges of Globalization: A Case Study of Cultural Resistance in New Zealand. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2000, 2, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, M.D.; Metz, J.L. Celebrating Humanity: Olympic Marketing and the Homogenization of Multiculturalism. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2001, 3, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Blain, N. Sport, Media, Culture: Global and Local Dimension; Fran Cass: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, J. Globalización y Creación del Deporte Moderno; Revista Digital EF Deportes: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2003; ISSN 15143465. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Traditional Sports and Games, Challenge for the Future: Concept Note on Traditional Sports and Games. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252837 (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Bronikowska, M.; Petrovic, L.; Horvath, R.; Hazelton, L.; Ojaniemi, A.; Alexandre, J.; Silva, C.F. History and cultural Context of Traditional Sports and Games in Selected European Countries. In Recall: Games of the Past-Sports for Today; Playing Traditional Games vs. Free-Play during Physical Education Lesson to Improve Physical Activity: A Comparison Study; Bronikowska, M., Laurent, J.F., Eds.; TAFISA: Poznan, Poland, 2015; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352764618_Playing_traditional_games_vs_free-play_during_physical_education_lesson_to_improve_physical_activity_a_comparison_study (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- O’Brien, J.; Holden, R.; Ginesta, X. Sport, Globalization and Identity. New Perspectives on Regions and Nation; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GinestaPortet, X. Les Multinacionals de L’entreteniment. Futbol, Diplomacia, Identitat i Tecnologia; UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kantar. 2021 Media Trends and Predictions. Available online: https://www.kantar.com/campaigns/media-trends-and-predictions-2021 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- GSIC. Data and Sports: A Marriage Made in Heaven, and the Cloud; GSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thorngate, W. The economy of attention and the development of psychology. Can. Psychol. Can. 1990, 31, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, P.M. Routledge Handbook of Sport Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Practical implications and future research directions for international sports management. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2011, 53, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.J.; Schultz, M. Toward a theory of brand co-creation with implications for brand governance. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomier, J. New media, branding and global sports sponsorship. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2008, 10, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Kim, E.; Mastromartino, B.; Qian, T.Y.; Nauright, J. The sport industry in growing economies: Critical issues and challenges. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2018, 19, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D.; Hutchins, B. Globalization and Online Audiences. In Routledge Handbook of Sport and New Media; Billings, A.C., Hardin, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.S.; Vincent, J. Globalisation and sports branding: The case of Manchester United. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2006, 7, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdop, P.; Chadwick, S.; Parnell, D. Guest editorial. Sport Bus. Manag. 2019, 9, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ratten, V.; Ratten, H. International sport marketing: Practical and future research implications. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2011, 26, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguiar-Noury, A.; García del Barrio, P. Global Brands in Sports: Identifying Low-Risk Business Opportunities. J. Entrep. Public Policy 2019, 8, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación de Marketing de España. Dictamen de Expertos Sobre Acceso al Contenido Audiovisual. 2020. Available online: www.asociacionmkt.es/evento/dictamen-expertosmkt-deporte-acceso-contenido-audiovisual (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- IQUII Sport. The European Football Club Report 2021. Available online: https://sport.iquii.com/pdf/EUROPEAN_FOOTBALL_CLUB_IQUIISPORT_JAN_2021.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Neira, E. Streaming Wars; Libros Cúpula: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, G.P.; Simmons, J.M.; Hambrick, M.E.; Greenwell, T.C. Spectator support: Examining the attributes that differentiate niche from mainstream sport. Sport Mark. Q. 2011, 20, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, G.P.; Greenwell, T.C. Professional niche sports sponsorship: An investigation of sponsorship selection criteria. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2013, 14, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenwell, T.C.; Greenhalgh, G.; Stover, N. Understanding spectator expectations: An analysis of niche sports. Int. J. Sport Manag. Market. 2013, 13, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mastromartino, B.; Wann, D.L.; Zhang, J.J. Skating in the sun: Examining identity formation of NHL fans in sunbelt states. J. Emerg. Sport Stud. 2019, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mastromartino, B.; Zhang, J.; Wann, D. Managerial perspectives of fan socialisation strategies: Marketing hockey to fans in sunbelt states. J. Brand Strategy 2020, 8, 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Miloch, K.S.; Lambert, K.W. Consumer awareness of sponsorship at grassroots sport events. Sport Mark. Q. 2006, 15, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, A.; Hardin, M. Routledge Handbook of Sport and New Media; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://bit.ly/307Rb07 (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Petrović, L.T.; Milovanovic, D.; Desbordes, M. Emerging technologies and sports events. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2015, 5, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Dos-Santos, M.; Rejón-Guardia, F.; Campos, C.P.; Calabuig-Moreno, F.; Ko, Y.J. Engagement in sports virtual brand communities. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, A.; Blakey, P. Digital Sport Marketing: Concepts, Cases and Conversations; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, B.; Greenhalgh, G.P.; Lecrom, C.W. Exploring Fan Behavior: Developing a Scale to Measure Sport eFANgelism. J. Sport Manag. 2015, 29, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, D.L. The causes and consequences of sport team identification. In Handbook of Sports and Media; Raney, A.A., Jennings, B., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 331–352. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, B.D. Socialization into the role of sport consumer: A theory and causal model. Can. Rev. Sociol. Can. Sociol. 2008, 13, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, D.L.; Tucker, K.B.; Schrader, M.P. An Exploratory Examination of the Factors Influencing the Origination, Continuation, and Cessation of Identification with Sports Teams. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1996, 82, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, R.; James, J.D. An Identification and Examination of Influences That Shape the Creation of a Professional Team Fan. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2000, 2, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, K.D.; Koch, E.C. A conjoint approach investigating factors in initial team preference formation. Sport Mark. Q. 2009, 18, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Groeneman, S. American’s Sports Fans and Their Teams: Who Roots for Whom and Why; Seabird Press: Lexington, KY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Melnick, M.J.; Wann, D.L. Sport fandom influences, interests, and behaviors among Norwegian university students. Int. Sports J. 2004, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Introduction: Innovation and entrepreneurship in sport management. In Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Sport Management; Elgar: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Social innovation in sport: The creation of Santa Cruz as a world surfing reserve. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2019, 11, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Mantras and myths: The disenchantment of mixed-methods research and revisiting triangulation as a perspective. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product; Routledge: AbIngdfon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, I. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Sports Fan Research. Qual. Rep. 1997, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, M.; Adler, R.W. Exploring the reliability of social and environmental disclosures content analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1999, 12, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Llopis Goig, R. El Grupo de Discusión; ESIC: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cea d’Ancona, M.A. Fundamentos y Aplicaciones de la Metodología Cuantitativa; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Corporació Valenciana de Mitjans de Comunicació (CVMC). Audiències de la Pilota Valenciana Any 2019; Working Paper; CVMC: València, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.-H. Retrospection and state of sports marketing and sponsorship research in IJSMS from 1999 to 2015. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2017, 18, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J. The Dynamics of Place Brands: An Identity-Based Approach to Place Branding Theory. Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolotouchkina, O.; Seisdedos, G. The Urban Cultural Appeal Matrix: Identifying Key Elements of the Cultural City Brand Profile Using the Example of Madrid. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2016, 12, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, J.; Jackson, S.J. Globalization, Sport and Corporate Nationalism: The New Cultural Economy of the New Zealand All Blacks; Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, B.; Rowe, D. Sport beyond Television: The Internet, Digital Media and the Rise of Networked Media Sport; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Universe | General Population Men and Women Aged 18 or Over | Fans of Valencian Pilota Men and Women Aged 18 or Over | Federated Players in the Last Few Years Men and Women Aged 16 or Over |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Valencian Country | Valencian Country | Valencian Country |

| Sample size | 670 | 473 | 325 |

| Sample error | +/− 3.8 for a 95.5% (2 sigma) confidence level with p = q = 50 | +/− 4.5 for a 95.5% (2 sigma) confidence level with p = q = 50 | +/− 5 for a 95.5% (2 sigma) confidence level with p = q = 50 |

| Technique | In-person survey using the CAPI system. Structured questionnaire lasting 10 min | In-person survey at match venues | In-person survey at match venues |

| Sampling | Multi-stage sampling: probability stratified by sizes of municipality and not probabilistic for age and sex quotas | Multi-stage sampling, probabilistic by conglomerates, not probabilistic for age and sex quotas 17 sampling points | Multi-stage sampling, probabilistic for territorial, age and sex quotas. 51 sampling points |

| Focus Group 1 | Focus Group 2 | Focus Group 3 | Focus Group 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Sports experts and trainers | Marketing and communication professionals | People involved in the sport | Researchers and publicists |

| No. of participants | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Profession of the participants | Teacher (2), federation officer (2), coach, technical director of club | Sports journalists (3), sponsor’s PR officer, sponsor’s communications director, communication officer for professional organisation | Professional players (2), manager of the governing body for professional championships, federation officer | Editor, cultural journalist, teacher/researcher, museum director, researcher/publicist |

| Club presidents | 3 |

| Amateur players | 2 |

| International player | 1 |

| Former professional players | 2 |

| Professional players | 2 |

| Sports promoters and business people | 4 |

| Managers of main organisations | 4 |

| Former directors of main organisations | 1 |

| Associated political leaders | 2 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Researchers/publicist | 3 |

| Sports journalists | 3 |

| Managers of TV companies with audiovisual rights | 3 |

| Newspapers | Digital Media | Radio | TV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| News items published | 128 | 155 | 9 | 12 | 304 |

| Percentage | 42% | 51% | 3% | 4% |

| Facebook 2016 | Facebook 2020 | Twitter 2016 | Twitter 2020 | Instagram 2016 | Instagram 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of official accounts with more than 500 followers | 8 | 45 | 8 | 16 | 6 | 36 |

| Cumulative no. of followers in all the accounts counted | 22,685 | 102,002 | 11,803 | 20,424 | 4571 | 48,098 |

| Profile with largest number of followers | 4178 | 10,319 | 2236 | 2236 | 1131 | 5729 |

| Basket Ball | Baseball | Soccer | Handball | Motorcycling | Traditional Sport | Rugby | Tennis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.4 | 46.9 | 9.1 | 17.6 | 20.9 | 27.0 | 48.8 | 14.14 |

| 2 | 5.8 | 14.0 | 3.3 | 7.6 | 9.0 | 14.8 | 15.7 | 4.8 |

| 3 | 6.3 | 9.4 | 4.2 | 9.6 | 7.3 | 9.1 | 9.99 | 5.7 |

| 4 | 5.2 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 6.6 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 6.0 | 6.4 |

| 5 | 17.5 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 18.1 | 15.4 | 13.1 | 9.6 | 14.9 |

| 6 | 8.7 | 3.9 | 8.1 | 13.0 | 11.3 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 11.3 |

| 7 | 10.6 | 2.8 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 6.3 | 2.7 | 13.7 |

| 8 | 14.6 | 2.4 | 19.0 | 9.3 | 8.2 | 6.3 | 1.8 | 13.6 |

| 9 | 5.2 | 0.9 | 10.3 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 5.7 |

| 10 | 13.6 | 2.8 | 21.6 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 9.0 |

| Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 31.7 | 35.3 | 23.9 | 7.5 | 1.7 |

| Women | 40.3 | 35.8 | 19.0 | 3.9 | 1 |

| Total | 35.7 | 35.5 | 21.6 | 5.8 | 1.3 |

| General Population | Fans | Federation-Registered Players | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family | 15.3% | 43% | 38.5% |

| Primary/secondary school | 38.8% | 4.9% | 9.8% |

| Friends | 37.8% | 38.4% | 36.6% |

| Municipal sports activities | 2% | 3.2% | 6.4% |

| Mass media | 1% | 0.6% | 1.8% |

| Sport events | 2% | 2% | 3% |

| Cultural association | 2.1% | 1% | 1% |

| Traditional sport club | 0% | 2% | 2.3% |

| Others | 0% | 5% | 0.6% |

| DN/NA | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| General Population | Fans | Federation-Registered Players | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of each audience which follows news about Valencian pilota in the media | 16.4% | 85.8% | 88.9% |

| Percentage of each audience which follows coverage in a particular medium | TV: 78% | TV: 76% | TV: 68% |

| Radio: 3% | Radio: 5.7% | Radio: 9% | |

| Press: 12% | Press: 27.3% | Press: 36.9% | |

| Digital: 10% | Digital: 23.9% | Digital: 4.6% |

| General Population | Fans | Average for Both | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | 3.1 | 4.4 | 3.75 |

| Schedules | 3 | 4.2 | 3.6 |

| Ticket price | 3 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

| Comfort | 3 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| Players | 2.9 | 4.5 | 3.7 |

| Information | 2.9 | 4.4 | 3.65 |

| Location | 3.1 | 4 | 3.55 |

| Bathrooms | 2.9 | 4.3 | 3.6 |

| Hospitality | 2.7 | 4.2 | 3.45 |

| Lighting/acoustics | 3.1 | 4.7 | 3.9 |

| Public transport | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.2 |

| Car park | 3 | 4.6 | 3.8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanahuja-Peris, G.; Agulló-Calatayud, V.; Blay-Arráez, R. David against Goliath: Diagnosis and Strategies for a Niche Sport to Develop a Sustainable Fan Community. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413594

Sanahuja-Peris G, Agulló-Calatayud V, Blay-Arráez R. David against Goliath: Diagnosis and Strategies for a Niche Sport to Develop a Sustainable Fan Community. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413594

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanahuja-Peris, Guillermo, Víctor Agulló-Calatayud, and Rocío Blay-Arráez. 2021. "David against Goliath: Diagnosis and Strategies for a Niche Sport to Develop a Sustainable Fan Community" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413594

APA StyleSanahuja-Peris, G., Agulló-Calatayud, V., & Blay-Arráez, R. (2021). David against Goliath: Diagnosis and Strategies for a Niche Sport to Develop a Sustainable Fan Community. Sustainability, 13(24), 13594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413594