Abstract

By the end of 2020, more than 80 million people were forcibly displaced around the world; this represents about one percent of the global population. Many of the displaced found shelter in emergency settlements; whether in refugee camps, IDP camps or community settlements. Some of these settlements are transitory, while others have been consolidated into permanent habitats; some span the size of a city, while others are the size of a village; some are well structured, while others provide only the bare minimum needed by residents. Notwithstanding these variations, there is still a lack of understanding of the range, depth, scale, and scope of these settlements. There is also a need for comparative analysis between different types of emergency settlements, as they are still generalized as temporary encampments. The aim of the study is to identify the distinctiveness of each type of emergency settlement to demonstrate that one strategy for their planning and management will not fit all. It does so by reviewing the criteria for analyzing emergency settlements around the world by using a quantitative analysis methodology on a set of variables considered relevant for the characterization of each typology based on a set of 500 cases. The results indicate that each type of emergency settlement has different characteristics and topology, and identify which variables, being identical, influence each typology differently. The article also discusses the basis for better-informed decision-making about the medium and long-term policies applicable to individual settlements.

1. Introduction

The movement of people is not a new problem or a recent occurrence. Over the centuries, it was customary for humans to move in search of food and better living conditions. Even in forced situations, people found ways to create viable shelters. However, this concept now faces new challenges of scale and exclusion of the refugees who are, according to the 1951 UN Convention, people “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership or a particular social group, or political opinion”.

Humanitarian actors concerned with helping displaced populations have struggled to respond to multiple crises plaguing different regions of the planet simultaneously [1]. Today, more than 80 million people are forced to leave their homes for different reasons, increasingly including the impacts of climate change. The increase in climate refugees as a phenomenon of international migration also occurs in reaction to more recent extreme environmental factors and due to war and famine [2].

For these populations, more than ever, the immediate option for finding shelter is in emergency settlements, which do not always meet the conditions of ethnic, cultural or religious balance. On the other hand, the scarcity of resettlement alternatives, partly due to the increased protectionism of potential host countries, is causing an increase in the number, size, and life of these emergency camps, with some consolidating into long-lasting settlements. This phenomenon of consolidation into large, dense and permanent communities has been accelerated by the substantial growth in the number of forcibly displaced populations and the postponement of emergency contexts [3].

Emergency settlements are seen and understood as transitory habitats with minimal conditions. This understanding means that their planning and management depend on temporary solutions, rather than measures and infrastructure capable of sustaining long-term occupation. There is also a failure to differentiate between the three known types of emergency settlement: refugee camp; internally displaced persons (IDP) camp; and community settlement, which tend to be generalized as “emergency camps”. Thus, these concepts are reflected in the design strategies, and often result in unsustainable and dehumanizing habitats.

1.1. Importance of Emergency Settlements

Until the 1970s, emergency settlements were analyzed using physical parameters and minimum performance standards. There was little theoretical or scientific investigation into the social, political, economic or environmental aspects of these types of settlements. The aforementioned perception started to change in the 1980s with Cuny, a disaster relief specialist who participated in many humanitarian projects around the world. Cuny thought that emergency settlements should be looked at through a holistic and cross-sectorial approach that takes into account the capacity for self-support and needs of the affected community [4].

A decade later, the Italian philosopher Agamben [5] published the book Homo Sacer, where he proposed a different perspective on emergency camps, that sets aside the physical aspects and focuses on the socio-political. Agamben considers camps as a place of exclusion with a hidden matrix and nomos of the political space in which we are still living, that is, they are an integral part of human society and a biopolitical paradigm of social life. His approach to the subject from a political angle opened the door for investigators to explore fields beyond the immediate normative and empirical factors.

Following Agamben, the French anthropologist Agier emphasized the importance of emergency camps, and their role as an integral part of human society and as a vanguard to develop human habitats. He had previously called refugee camps “unfinished urbanizations”, referring to the image of the countryside as a bare city [6]. In a more recent publication, Agier defined refugee camps as places of extraterritoriality, exception and exclusion, considering them as off-site spaces that transform their inhabitants, as well as the inhabitants of the region to which they belong. He also suggested that refugee camps are gradually creating a new global scenario, due to the increasingly common adoption of this solution by governments and international agencies to accommodate displaced people [7].

Other academics have proposed that the city and modern society cannot be understood without the refugee camp [8]. Sanyal [9] sees refugee spaces as quintessential geographies of the modern world and complex spaces that challenge the socio-spatial imagination of academics and practitioners. Picker and Pasquetti [10] highlighted the growing prominence of emergency camps as a feature of social landscapes across the world, alluding to the need for an interdisciplinary debate on their study, including geography, sociology and social anthropology, and calling for urban scholarship on camps. Some scholars have proposed new definitions of refugee camps, such as “transition settlements” [11], “political agencies” [12], “places of opportunity” [13], and “humanitarian urbanism” [14], arguing that they are like cities.

Most recently, Oesch [15] elaborated on Agamben’s conceptualization of exception to reconsider the idea of the emergency camp as a zone of indistinction between exclusion and inclusion by analyzing its subjectification within the framework of ambiguity. For Oesch, camp dwellers are autonomous and productive entrepreneurs and consumers. He also differentiated camps from cities by depicting them as spaces of multiple ambiguities and subjectivities, which represents a more general principle of governing camps. Oesch believes that camps differentiate from each other depending on the geo-political aspects, just as cities and towns do.

Although relevant to the understanding of emergency settlement, the aforementioned works and other investigations published thus far on the topic do not elaborate enough on the particularities of each type of emergency settlement, which can influence not only the way they are formed and develop, but also their status as transient spaces. An example is the political aspect of permanent infrastructure. In refugee camps, that aspect is connected to the consideration of the camps as temporary spaces, as well as to the way they are represented to surrounding communities. These political aspects are inherently different in settlements for internally displaced persons and in community settlements.

1.2. Types of Informal Settlements, Reasons for Their Existence, Planning and Establishment

Three main kinds of event provoke exodus: conflict, natural disaster, and famine. The options for shelter for those forced to abandon their homes are divided into two main categories: dispersed and grouped. Dispersed sheltering can be taken in host families and rural or urban self-settlement. Grouped sheltering can be taken in existing communities in collective centers or designated areas, or in new settlements established formally or informally during emergencies in the form of encampments.

Whenever possible, forcibly displaced people try to take refuge with relatives or acquaintances who live far enough from conflict zones or challenging environments. Others gravitate to urban centers, due to the higher quality of basic services that cities can offer, such as security, education, health, and housing, better job opportunity, and to avoid day-to-day life restrictions in other people’s homes or camps [16]. Emergency settlements are quite often the last resource. They are particularly appealing to refugees who do not feel safe in their own country or people who cannot travel long distances, especially the most vulnerable, such as the elderly, the disabled, and single mothers and their children. For instance, more than half of all people currently living in refugee camps are under 18 years old [17].

Regardless of the reason for their implementation, these settlements can be created in two different ways: planned or self-settled. Planned settlements are either established by authorities as an immediate response to an emergency or planned in advance, whereas self-settled camps are informally established by shelter seekers. Emergency settlements also differ according to the status of their inhabitants, who can be classified as refugees or internally displaced persons (IDPs). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) considers IDPs as ousted people who remain uprooted within their own country, whilst refugees leave their country of origin or habitual residence in search of shelter.

The main factors that influence the location of camps that cater for IDPs are avoidance of risky areas susceptible to the same cause of the displacement; the availability of at least 45 square meters of space per person; topography with a gradient between one and five per cent, in order to avoid flooding; proximity to a water source; and facility of access to assistance. Besides the aforementioned factors, refugee camps should be located at least 50 km from the border due to security issues [17]. In many cases, isolation from existing settlements is also taken into consideration. Regarding refugee camps, quite often they are established in areas that have been discarded for future exploration by local government; hence, these are challenging environments with few resources.

According to UNHCR [18], no camp should be larger than 20,000 people. Due to the unpredictable nature of emergency events, many camps surpass the proposed size several times over. Settlements set up by authorities generally have a military-style grid layout, which consists of plots (5 to 10 people), blocks (100 to 120 plots), and sectors (8 to 10 blocks) [19]. The main reasons for the employment of this approach are the facility of setting up, and ease of circulation, especially for humanitarian assistance and in case of emergency evacuation. Another reason for the use of grid systems is to facilitate the control of its inhabitants. Consideration of strategies to dismantle the camps should also be part of their planning, especially when they are seen as temporary habitats; however, this aspect is rarely taken into consideration.

Due to the prolonged lifespan of emergency settlements, many of their original characteristics evolve over time, which provides them with particular features. For instance, their layout become more organic, the demographics change, and infrastructures are developed [20]. An example of this phenomenon can be witnessed in Kakuma refugee camp, Kenya where shelters inside older blocks are no longer in a grid system but arranged in groups that form small clusters. In other cases, the changes are in reverse, such as in Kutupalong refugee camp, Bangladesh where parts of the camp established in an organic way are going through spatial reorganization to facilitate circulation and prevent the spread of fire. These changes occur more often in refugee camps than in other types of emergency settlement.

The way changes consolidate in each type of emergency settlement define what they become. An understanding of what they develop into can better inform their planning and management, and indicate which are potentially sustainable and should be supported in the long-term, and which ones are not sustainable in the long run.

The main objectives of this study are two-fold: to better characterize emergency settlements by sharing highly significant and comparative universal information, such as settlements’ average lifespan, demography and location; and to discuss and understand how the average lifespan of settlements, population, and location can be used as information to improve policy formulation on key questions such as whether emergency settlements should continue to be exclusively determined, planned and managed as temporary encampments or on the contrary, evaluated to determine whether some should be permanent in response to problems broader than migration.

Another aspect that deserves more attention is that of gender and settlement. Emergency settlements are paramount for people’s safety, especially for mothers who have lost husbands in conflicts and their children, and young girls who are some of the most vulnerable in relation to gender-based violence. The results of this article can also be used to highlight this issue and instigate policy and design to address it.

2. Materials and Methods

An analysis and review of the plan and operation system of emergency settlements was adopted as a systematic review and meta-analysis research methodology, in order to identify the relevant strategies and variables applied to the theme of emergency settlements.

This investigation identified and analyzed the measurable and non-measurable features of 501 emergency settlements, of which 377 were open and 124 were closed at the time of the investigation. The data were collected in the first quarter of 2020 and reflect the situation of the settlements in 2019.

The settlements were divided into three main groups: refugee camps, which are settlements that accommodate refugees; IDP settlements, which are settlements that accommodate forcibly displaced people in their country of origin; and community settlements, which are settlements adjacent to existing communities, which share most of their facilities and host refugees or IDPs. Camps managed by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) in Palestine and Lebanon, which cater for Palestine refugees were not included in the data set as due to their particular situation, they are influenced by political, social, and economic aspects, and most of them have amalgamated with existing cities, thus these camps no longer function as isolated settlements.

A set of variables considered noteworthy for the characterization of each settlement was used as the basis for the data collection. Those variables included geographical position (country, locality, latitude/longitude, climate), which determines where each type of settlement is currently located; situation (opening/closing date, size, population), which is used to calculate their lifespan and verify their endurance, and density as indicative of the level of social interaction among residents; background (motive, displaced condition, origin/ethnic group), which distinguishes the circumstances in which each settlement was formed; and demographics (gender and age range), which shows the level of connection to the places and vulnerability of their residents. Lifespan was calculated as the time from the opening date to the closing date, or the opening date to June 2020, for the settlements still open at that time.

The data was sourced from the UNHCR archive and data portal [21], documents and reports from other humanitarian institutions, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and Oxfam, as well as from periodicals and academic papers, through electronic search engines, library visits, and recommendations from experts on the topic. Geographical data was harvested from reliable sources, such as Google Maps [22] for latitude and longitude, and climate data [23] was searched for climate information.

In refugee complex scenarios where the settlement consists of a cluster of small communities, each community was considered as an individual camp if it had particular characteristics and was considerably distant from others, for instance, in cases where some communities were self-settled, and some were planned. This happened in complexes, such as Dadaab and Dolo Ado. When the communities were too close to each other to be considered individual camps, such as the Rhino camp and Adjumani camp, their data were amalgamated, and the refugee complex was treated as a unique settlement. In cases where the demographic percentage or the size of a certain settlement could not be found, the figure adopted was the average of the data from other settlements in the same region.

The data collected were collated in a spreadsheet [24]. References from data collected on each settlement is available in the Emergency Settlement Catalogue [25].

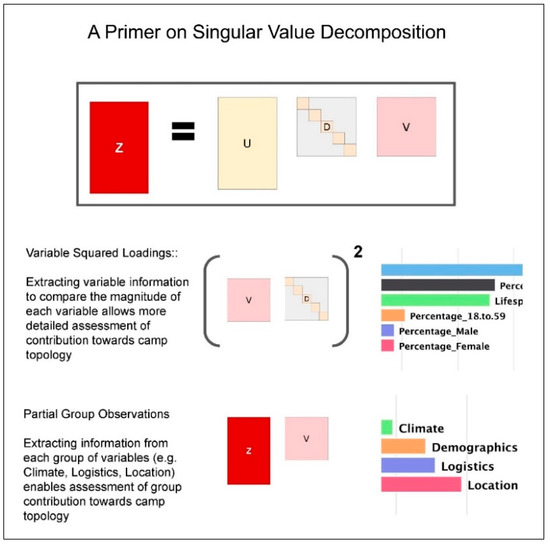

The investigation makes use of quantitative analysis of the data gathered through the application of statistical distribution and modelling to analyze and decode each type. The statistical distribution analysis results were obtained by estimating the percentage, average, and standard deviation, using Excel software as the calculation tool. The modelling was done by multivariate data analysis, using R programming language. This process was done by singular value decomposition, which is an algorithm for finding the most important interactions and relationships in the data. The decomposition presents the sub-components on a Cartesian plane for topology interpretation. Further information about the modelling calculation process can be found in Appendix A or in the article Multivariate Analysis of Mixed Data: The R Package PCAmixdata [26]. The plots generated by the R programming language were separated per emergency settlement type and are available online [27].

Interviews with the staff and residents of emergency settlements complements the research methodology with factual information. The interviews, which were conducted during 2020, were done online and via phone and email, informally and through purposed questionnaires. Due to the closure of emergency settlements as a response to the global pandemic, it was not possible to do the ethnographic fieldwork in person.

3. Results

The results of the quantitative analysis presented next have been separated by statistical methods: distribution and modelling.

3.1. Statistical Distribution

The statistical distribution analysis focused on geographical location, lifespan, density, and the demographics of the emergency settlements investigated. The objective of this analysis was to establish their most likely location, duration, and characteristics as a way to assist in their conceptualization and distinguish one from another.

3.1.1. Geographical Location

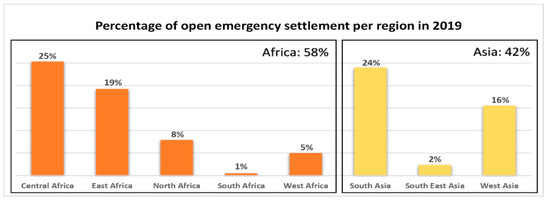

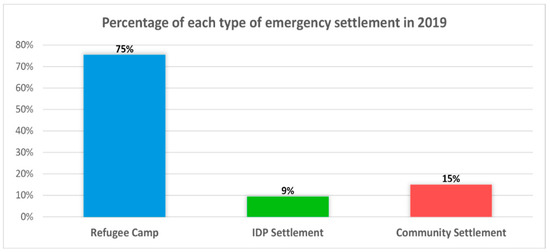

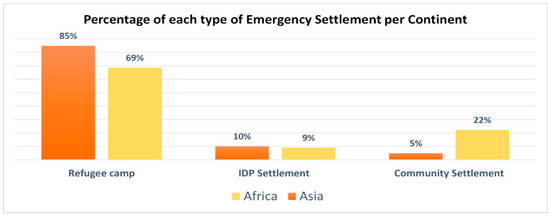

The analysis of the location of emergency settlements that are currently open provides an indication of which type is most common per continent, region and climate [28]. The results depicted in Figure 1 show that most emergency settlements that are currently open are in Africa (58 per cent). Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that refugee camps are the most common type (75 per cent), and are more common in Asia (85 per cent) than in Africa (69 per cent).

Figure 1.

Graph showing the percentage of open emergency settlements per region in 2019.

Figure 2.

Pie chart showing the percentage of each type of emergency settlement open in 2019.

Figure 3.

Graph showing the percentage of each type of emergency settlement per continent in 2019.

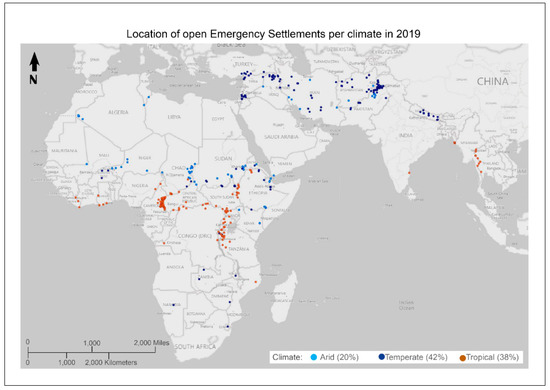

The results also show that most emergency settlements that are currently open are in temperate (42 per cent) or tropical (38 per cent) climates (Figure 4); however, the most common type of climate for emergency settlements differ from continent, with African settlements present mostly in tropical climate, whereas Asian settlements are present mostly in temperate climate. This result shows that despite the great majority of emergency settlements being located either in the tropical or sub-tropical regions, in general, their concentration is not related to a specific climate.

Figure 4.

Map showing the location of open emergency settlements in 2019 and the respective climate.

3.1.2. Average Lifespan

The analysis of average lifespan gives an indication of what type of settlement is more likely to endure, therefore, they are susceptible to consolidate into a long-lasting habitat [29]. The analysis is also used to corroborate the proposition that emergency settlements should not be assumed to be temporary.

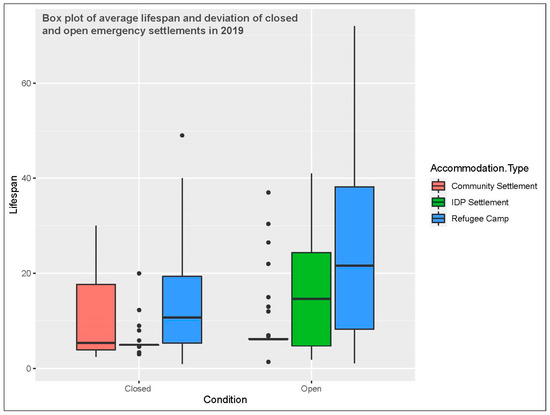

The results shows that open emergency settlements currently have an average lifespan of 20.8 years with a standard deviation of 16.1 years, whereas closed ones had been open on average for 12.1 years with a standard deviation of 10.7 years (Figure 5). This result not only validates the affirmation that emergency settlements are no longer transient habitats, since they have a high average lifespan, but also gives the indication of a trend of continuity, demonstrated by the fact that camps opened more recently are lasting longer than the ones opened in the past.

Figure 5.

Graph showing the average lifespan in years of closed and open emergency settlement on June 2020 per type and grand average.

Regarding types of settlements, open refugee camps have longer lifespan (23.8 years with standard deviation of 16.7 years) than IDP settlements (15.5 years with standard deviation of 11.2 years) and community settlements (8.8 years with standard deviation of 6.6 years).

The standard deviation represents the amount of spread of the set of values, which is this case is lifespan in years. The smaller the variation, the closer the data points are to the average, giving a more reliable estimate. A coefficient of variation above 70 per cent in the analysis certifies the reliability of the estimation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Boxplots of average lifespan and deviation of closed and open emergency settlements.

Regarding community settlement, this research identified 57 open settlements. Of those, 42 have a lifespan of 6.2 or 6.3 years. All of these cases are located in Cameroon and are the result of one conflict in the Central Africa Republic; hence, they have a similar lifespan. In that particular case, the high amount of a type of settlement in the same condition does not give the desired representativeness; however, the high accuracy of that data is not relevant. Similar cases can be noted in the closed IDP settlements, where most of them had a short lifespan in the past.

In terms of refugee camps, this study identified 119 camps that opened in the last decade (2010 to 2019) and 70 camps that opened in the previous one (2000 to 2009), representing an increase of 70 per cent in the number of camps that opened from one decade to another, whereas the number of camps that closed remained almost the same (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data on opening and closure of refugee camps in the last two decades.

The authors of this study did not identify any other piece of work that has provided a quantitative analysis on the average lifespan of emergency settlements. Several media publications state that the average lifespan of a refugee camp is 17 years. This figure comes from the UNCHR publication, The State of the World’s Refugees [30], which in turn is sourced from another UNHCR internal document entitled Protracted Refugee Situations [31]. The text reads: “It is estimated that the average duration of major refugee situations, protracted or not, has increased: from 9 years in 1993 to 17 years in 2003.” and does not actually relate to refugee lifespan, but to the average duration of major refugee situations. This research is the first published study to provide a figure of the average lifespan of currently open refugee camps (23.8 years), based on data collected from 286 settlements.

As emergency settlements are constantly opening and closing, a proposed fixed lifespan figure for this type of habitat is unlikely to be representative. The calculation would have to keep taking into consideration recently open settlements, which have a shorter lifespan, bringing down the average figure. However, rather than a fixed figure, the most important information taken from this analysis is the confirmation of the longevity of emergency settlements, especially refugee camps. This confirmation ought to be the catalyst for change in the strategies applied to their planning and management, moving from temporary to likely long-lasting scenarios.

3.1.3. Average Density

According to Mumford [32], to be considered urban, a settlement should be more than a certain size and it requires a certain level of complexity and diversity, which is mostly found in sites with high density. Density analysis gives an indication of the level of concentration of people in emergency settlements, and whether the complexity and diversity meet the criteria to be considered urban realms.

Table 2 shows that currently open emergency settlements have an average density of 9849 people per square kilometer with a standard deviation of 10,285 people per square kilometer, which is higher than many cities, such as Mexico City with 6000 people per square kilometer, Tokyo with 6224 people per square kilometer, or São Paulo with 7216 people per square kilometer [33]. IDP settlements have higher average density (18,423 people per square kilometer with a standard deviation of 15,303 people per square kilometer) than refugee camps (9746 people per square kilometer with a standard deviation of 9487 people per square kilometer), whilst community settlements have lower density (5199 people per square kilometer with a standard deviation of 6686 people per square kilometer).

Table 2.

Density (people per square kilometer) of emergency settlement per continent.

Similar to the lifespan calculation, a coefficient of variation of above 70 per cent certifies the reliability of the estimation.

Although social connectivity is currently undergoing a change through the dissemination of social media, denser environments still favor social connection. When considering lifespan and density together, it can be noted that some settlements have enough human concentration and duration to foment the complexity and diversity required to be considered urban areas. The analysis also shows similarities between the average density of camps in Asia and Africa, which indicates a consistent feature that can be used in the planning and management of these types of settlement across the globe. Another observation, presented in Table 3, is that older settlements have lower density than newer ones, showing a natural equilibrium of distribution of people over the time, either by an expansion in the campsite or a reduction in inhabitants through repatriation or resettlement programs.

Table 3.

Average density (people per square kilometer) of emergency settlement per lifespan.

3.1.4. Demographics

Vulnerability relates to populations at most risk of being unable to satisfy their basic needs, to access resources, or exercise their rights. In the humanitarian sector, the concept is primarily applied to those who are considered the most vulnerable, such as women, children, the elderly, or people with disability [34]. For instance, adolescent girls are at increased risk of sexual violence or forced marriage across humanitarian contexts [35]. Spatial, sector-specific data can be analyzed through statistics to improve the understand of the needs of vulnerable populations, refine research target, and enhance programmatic intervention [36]. The analysis of demographics assists in the understanding of the diversity of gender and age groups in emergency settlements, and consequently, in the development of strategies that cater for the right constituent. The analysis can also show the level of vulnerability of residents through the percentage of those who are more susceptible to exploitation, such as women, children, and the elderly. Other information that can be taken from the analysis of demographics is the percentage of residents who were born in those settlements, in order to determine how connected its population is to those places.

The results show that on average, the distribution of men and women is balanced; however, in some cases, the differences are up to fourteen per cent, as in South African (region) camps, which are highlighted in red in Table 4. Therefore, equal numbers of women and man in emergency settlements cannot be assumed.

Table 4.

Percentage of males and females per emergency settlement type and region.

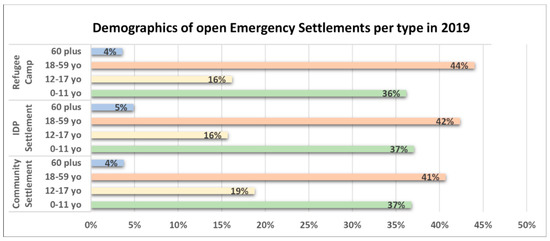

Regarding age range, there are fewer elderly people (over 60 years old) in emergency settlements (4 per cent) than the global average (13.5 per cent), whereas the percentage of children in those communities (37 per cent) is higher than the global average of 30 per cent [37]. The percentage of vulnerable groups (children, women, and the elderly) can reach up to 76 per cent in emergency settlements (see Figure 7). This result highlights the importance of considering security when planning for an environment with such a high percentage of people at risk. Regarding connectivity to the place of living, 49 per cent of residents of refugee camps with a lifespan over 18 years are children (under 18 years old), thus they were born in the camp. Those people will have not known any other place as they become adults.

Figure 7.

Graph showing demographics percentage in open emergency settlements in 2019 by type.

3.1.5. Social Diversity

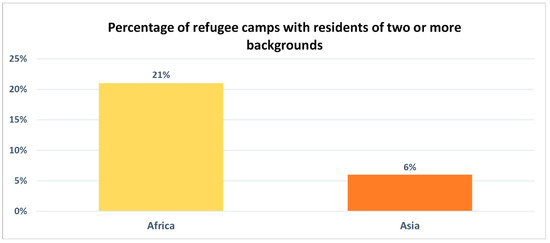

One of the ways of verifying the degree of urbanization of a settlement is through the level of diversity of its society. This aspect can be verified through the analysis of the background of its constituents. Settlements with constituents of multi-ethnic background, be it country, region, ethnicity, tribe, or clan tend to be more culturally diverse. and therefore, meet the criterion for social diversity to be considered an urban settlement [38]. Figure 8 indicates the percentage of refugee camps that have residents from at least two or more backgrounds.

Figure 8.

Graph showing the percentage of refugee camps with residents of two or more backgrounds per continent.

The results show that 21 per cent of the camps in Africa have a diverse society with residents coming from more than one ethnic group or country. An example is Kakuma in Kenya, which has residents from more than 10 countries. This diversity is not as prominent in Asia, with only six per cent of camps having a diverse society. It can then be established that when taking into consideration the level of social diversity, African settlements are more likely to have closer similarities to towns and cities, in which diversity is one of the prominent characteristics, whereas Asian settlements are more likely to have closer similarities to villages.

Regarding IDP settlements, the diversity in those settlements is almost nonexistent, as expected, as their inhabitants did not to cross international borders, and tend to come from the same region, leading to the conclusion that those settlements are more likely to function as villages or small towns, depending on their size and lifespan.

3.2. Statistical Modelling

An interactive tool for modelling the dataset [27] was developed with the same variables used in the distribution analysis: location (continent, country, region, area, latitude, and longitude), altitude, climate, average temperature and rain, lifespan, size (square kilometer), population, density (people per square kilometer and square meter per person), cause, event, reason, country and ethnic origin, and demographics (age range and gender). The analysis of refugee camps also includes infrastructure and governance aspects.

The tool, in the form of a dashboard for interpretable statistics, was developed using the modelling software PCAmixdata [39], employing R programming language.

Through the software, a multivariate data analysis was conducted in the form of principal component analysis (PCA), where metrics are used to introduce weights on the columns (variables) and on the rows (observations) of the data matrix, generating an x and y value, from zero to one for each variable, and representing them in a Cartesian coordinate. Those values were calculated by comparing each variable with all the others and finding out how closely it is related to each one when conducting the same analysis.

The level of the relationship between each variable is determined by how close the x and y value are from one another on the plane. For instance, when comparing physical size and location (country) of each refugee camp, large sites did not often relate to a specific country; therefore, they are not close related, showing that there is a great variety in camp sizes in the same region. On the other hand, climate and average temperature have close x, y values, as expected, as both variables are naturally related.

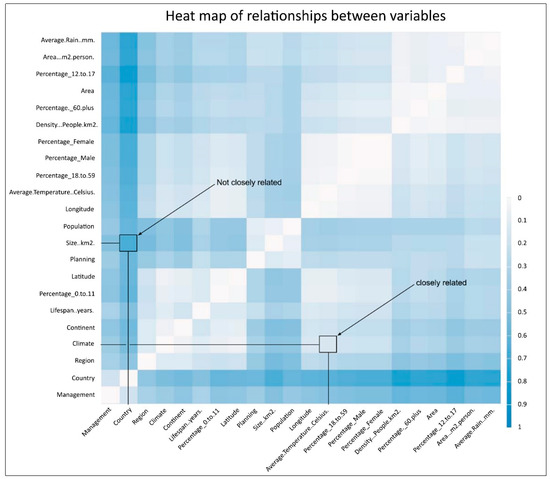

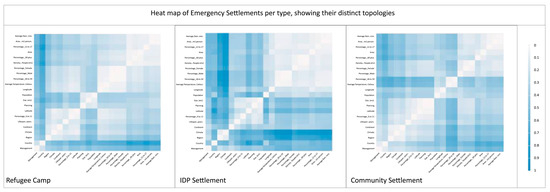

From the Cartesian coordinates, a heat map was generated using the distance between points of the coordinate graph, as another way of showing the relationship between variables. Figure 9 represents an example of a heat map using the aforementioned method. The smaller the distance in the Cartesian coordinate, the lighter the square, representing a closer relationship between variables.

Figure 9.

Example of heat map with relationship between variables in an emergency settlement.

Analyzing the heat map, it is clear as to which variable is closely related or not to another variable. The heat maps that follow (Figure 10) represent the topology of refugee camps, IDP settlements, and community settlements, showing that different types of emergency settlements have different topologies. Topology can be interpreted, in this case, as the arrangement of the variables of a dataset and how each one relates to another. Topology data analysis is an approach to the analysis of datasets using techniques from topology.

Figure 10.

Heat map-showing relationships between variables of emergency settlements, representing the topology of each type.

When comparing the three representations, it is clear that each type of settlement has a different topology, confirming their distinctiveness. By analyzing each representation, one can understand the level of the relationships among variables.

Regarding refugee camps, there are more closely related variables than not, which shows more consistency, and therefore stronger characteristics. The main assertions derived from the analysis are:

- The physical size (square kilometer) of a refugee camp is closely related to its population size and the way it was formed (planned or self-settled), but it is not closely related to most of the other variables, such as location;

- The location of a refugee camp (latitude/longitude) is not closely related to size (physical or population), but is closely related to most of the other variables, including the percentage of children and women, indicating that the population of certain areas are more vulnerable than others;

- The lifespan of a refugee camp is not related to a continent or country, showing that this type of settlement can be established anywhere, but it is closely related to climate.

Regarding IDP settlements, the variables of the cases analyzed were less related to one another, making them more diverse than refugee camps. Other assertions are:

- The physical size (square kilometer) of an IDP settlement is not closely related to its location (country, latitude/longitude, climate), but it is closely related to other variables, such as population size and demographics;

- The location (latitude/longitude) of an IDP settlement is not closely related to most variables, with the exception of the percentage of teenagers (12 to 17 years old);

- The lifespan of an IDP settlement is not closely related to location (country, latitude/longitude, climate), but it is closely related to population size and demographics.

Regarding community settlement, there is a balance between the numbers of variables that are closely and not closely related to another. Other assertions are:

- The physical size (square kilometer) of a community settlement is not closely related to its population size or demographics, but it is closely related to most of the other variables;

- Latitude and longitude of community settlements have different relationships to other variables, opposite to camps and IDP settlements, where those variables have similar responses. For instance, demographics are closely related to latitude but not longitude;

- The lifespan of a community settlement is closely related to size, location (continent), and percentage of male and female, but is not closely related to its population size or density.

4. Discussion

The results from the distribution analysis confirms not only the longevity of emergency settlements, but also the individuality of each type, which presents different results from investigation of the chosen variables. The result of their lifespan calculation revealed an average duration of almost 21 years, suggesting that emergency settlements should not necessarily be understood or considered as transient. Long lifespan and potential consolidation have been increasingly related to refugee camps more than other types of emergency settlements, but are not associated with a particular location or population size. This implies that the planning and management of emergency settlements might require further examination regarding their continuance, when compared and confronted with Sustainable Development Goals [40].

The statistical modelling corroborates the theory confirmed by the distribution analysis that each type of settlement has its own characteristics, through the unique representation of their topology, and the particular way in which variables influence each emergency settlement. This exposes the importance of considering the heterogeneity of sheltering responses in emergency situations when shaping the policy for planning and management of emergency settlements, as well as the need to address violence, education, and health care services with important supportive policies.

Besides these important findings, the study also revealed that the older the emergency settlement, the more resemblance it carries to permanent ones, regarding density, demographics, and level of development. The study has not only confirmed the theory of Oesch that emergency settlements differentiate from one another just as cities and towns do, but also determined that consolidated refugee camps tend to emulate cities and towns, not only in terms of density, but also in terms of socio, economic, and political complexity, whereas consolidated IDP encampments and community settlements are inclined to be more similar to villages, which are being culturally uniform and simply structured. This information could be of great assistance in the implementation of day-to-day strategies for the management of these settlements and provide useful means of applying criteria to enable the implementation of sound policies.

In terms of sustainable consolidation, it is possible to recognize the development of some emergency settlements into cohesive and interconnected communities. This can be demonstrated through the achievement of a reasonably good level of economic, environmental, social and political sustainability [41].

Economic sustainability was demonstrated by the self-reliance of residents in some settlements. For instance, the fact that Kakuma residents have developed their own banking system to tackle the lack of this service, which is crucial for the economic development of the settlement [42]. However, the continuing dependence of some camp residents on external assistance reveals that not all camps can be considered sustainable.

In terms of environmental sustainability, some camps have implemented sustainable strategies, such as solar cooking [43], thus reducing the need for wood, local water harvesting, which reduces the need for transported water, and wastewater treatment.

Social sustainability has been acquired and cultivated through community development, such as democratic selection of leaders and establishment of religious and recreational activities, as witnessed in some refugee camps, although in others the archaic and undemocratic systems derived from the ethnic structure of their homeland still remains [44].

The political aspect of emergency settlements previously discussed by researchers, such as Agamben, Agier and Turner can be confirmed through changes in the environment, as a sign of a desire by residents to imprint their individuality.

Limitations

One of the comments in this study was about the problems with the generalization of emergency settlements, and a lack of more specific information on their variants. The quantitative analysis methodology used in this study provides better insight into emergency settlements but offers only relative information. The aim of the study was to demonstrate that each type of emergency settlement has its distinct characteristics; therefore, the researchers consider that the methodology applied to reach the goal was appropriate. However, the study does not produce results that address the generalization of each type of settlement. For instance, not every refugee camp is the same, and generalizing them as such is also inaccurate. Those aspects will only be achieved through a thorough investigation on each type of individual settlement.

5. Conclusions

The investigation, in the context of a quantitative analysis of measurable and non-measurable variables in three types of emergency settlements (refugee camp, IDP encampment, and community settlement) allowed the identification of the characteristics of each variant, and established their similarities and differences, thus rectifying a lack of systematic definition of emergency settlement.

The results make it evident that these settlements should not be generalized as permanent or automatically assumed as temporary. The investigation also provides crucial sources of well classified information as the basis for better informed decision making on the medium- and long-term policies for individual settlements.

The nature of the long-term duration and particularity of each emergency settlement requires humanitarian organizations to change the standardized procedures that are applicable to temporary solutions. The actions of mass migration and large-scale internal displacements, which are possible to anticipate today as a result of geopolitical contexts and climate change, should lead to the fact that forced mobility of people can have integrated support from international entities, both in technical and logistical terms.

Emergency denotes a state of temporality; however, this investigation clarifies that most emergency settlements, particularly refugee camps, are no longer transitory habitats. Thus, planning and construction actions need to anticipate possible phasing in the implementation stage and the requirements to be assured in the management model, given that the period of use may well to be very long. It is, therefore, crucial to incorporate urban planning strategies and the optimization of infrastructure networks in the decision-making process to support the management model.

Besides helping to demystify a type of settlement that is currently erroneously assumed to be rudimentary, this research also provides a knowledge base to support the construction of responses with the capacity to be implemented not only immediately, but fundamentally, in the long term.

Through case studies, complementary qualitative research can reinforce the above-mentioned deductions. Comparisons with formal settlements, such as villages, towns, and cities can reveal which features are similar to emergency settlements, and which features are unique to them. This analysis can inform which strategies used in long established settlements can also be used in consolidated emergency settlements, and which strategies should not be applied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.; methodology, A.D., D.B., P.H., M.A.; software, D.B.; validation, A.D., D.B., P.H., M.A.; formal analysis, A.D., M.A.; investigation, A.D.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, A.D., D.B., P.H., M.A.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly accessible datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13271819.v1 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank proofreaders, and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The statistical distribution analysis results were obtained by percentage and average calculation.

The percentage (p) calculation was performed by applying the equation below, where x is the frequency of a case and n the total number of cases.

The average (A) calculation was performed by applying the equation below, where n is the number of values and ai are the data set values.

The variance calculation was performed by applying the equation below, where S is the sample standard deviation, is the sample mean, xi represents the individual values, and N is the size of the samples. The sample standard deviation calculation was performed by applying the square root of the variance.

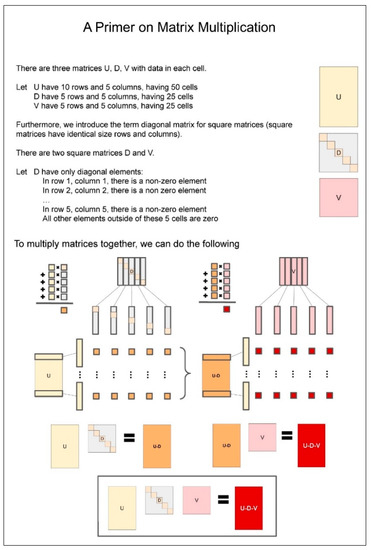

Figure A1.

Diagram explaining the process of matrix multiplication.

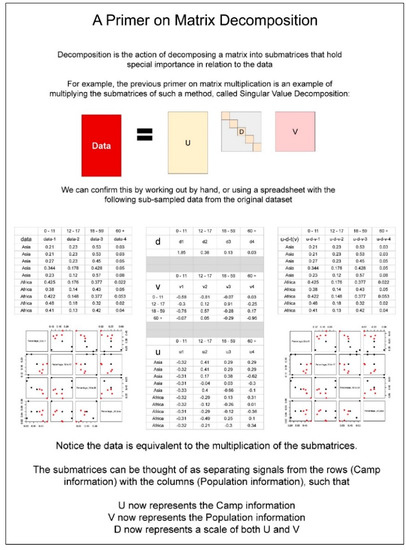

Figure A2.

Diagram explaining the process of matrix decomposition.

Figure A3.

Diagram explaining the process of singular value decomposition.

References

- Ferris, E.G.; Kirisci, K. The Consequences of Chaos: Syria’s Humanitarian Crisis and the Failure to Protect, The Marshall Papers; The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-8157-2952-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, M. Climate Change Refugees. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 2014, 17, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/flagship-reports/globaltrends/globaltrends2019/ (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Shawcross, W. A Hero of Our Time. New York Review of Books. Available online: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1995/11/30/a-hero-of-our-time/ (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Agamben, G. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Agier, M. Un Monde de Camps; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 64–350. ISBN 9782707183224. [Google Scholar]

- Agier, M. Between War and City: Towards an Urban Anthropology of Refugee Camps. Ethnography 2002, 3, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diken, B.; Laustsen, C.B. The Culture of Exception: Sociology Facing the Camp; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 244. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal, R. Urbanizing Refuge: Interrogating spaces of displacement. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Picker, G.; Pasquetti, S. Durable camps: The state, the urban, the everyday. City 2015, 19, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsellis, T.; Antonella, V. Transitional Settlement: Displaced Populations; Oxfam Books: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, M. From Camp to City: Refugee Camps of the Western Sahara; Lars Müller Publishers: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S. What Is a Refugee Camp? Explorations of the Limits and Effects of the Camp. J. Refug. Stud. 2016, 29, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, B. The protracted refugee camp and the consolidation of a humanitarian urbanism. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 42, 3. Available online: https://www.ijurr.org/spotlight-on/the-urban-refugee-crisis-reflections-on-cities-citizenship-and-the-displaced/the-protracted-refugee-camp-and-the-consolidation-of-a-humanitarian-urbanism/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Oesch, L. The refugee camp as a space of multiple ambiguities and subjectivities. Political Geogr. 2017, 60, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.; McIntyre, J.; Awidi, S.J.; De Wet-Billings, N.; Dixon, K.; Madziva, R.; Monk, D.; Nyoni, C.; Thondhlana, J.; Wedekind, V. Compounded Exclusion: Education for Disabled Refugees in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2017/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Emergency Handbook—Camp Strategy Guidance (Planned Settlements). Available online: https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/36256/camp-strategy-guidance-planned-settlements (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Daher, E.; Kubicki, S. Technologies in the planning of refugees’ camps: A parametric participative framework for spatial camp planning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Canada International Humanitarian Technology Conference (IHTC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 21–22 July 2017; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Huyck, E.E.; Bouvier, L.F. The Demography of Refugees. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1983, 467, 39–61. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1044927 (accessed on 1 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Operational Data Portal—Refugee Situations. Available online: http://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Climate-Data.Org. Climate Data for Cities Worldwide. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Dantas, A. Figshare. Emergency Settlements—Raw Data. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13293419.v1 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Dantas, A. Figshare. Emergency Settlement Data. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13271819.v1 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Chavent, M.; Kuentz-Simonet, V.; Labenne, A.; Saracco, J. Multivariate Analysis of Mixed Data: The R Package PCAmixdata. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1411.4911. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1411.4911.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Banh, D.; Dantas, A. Parameters of Interest for Refugee Data. Available online: https://www.askexplain.com/parameters-of-interest-for-refugee-data (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Yassin, N.; Osseiran, T.; Rassi, R.; Boustani, M. No Place to Stay? Reflections on the Syrian Refugee Shelter Policy in Lebanon; UN-Habitat: Beirut, Lebanon, 2015; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/112451 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Warren, C.J.; Douglas, R.L.; Oliver, P.; Heather, R.C.; Patricia, J.; Tatem, A.J. Classifying settlement types from multi-scale spatial patterns of building footprints. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 1161–1179. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. The State of the World’s Refugees 2006: Human Displacement in the New Millennium; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/publications/sowr/4a4dc1a89/state-worlds-refugees-2006-human-displacement-new-millennium.html (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- UNHCR. Protracted Refugee Situations; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/40c982172.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Mumford, L. The City in History. In Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects; Harcourt: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff, G. Rendering the World Unsafe: “Vulnerability” as Western Discourse. Disasters 2001, 25, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, E.; Ward, L.; French, S.; Falb, K. State of the Evidence: A Systematic Review of Approaches to Reduce Gender-Based Violence and Support the Empowerment of Adolescent Girls in Humanitarian Settings. Trauma Violence Abus. 2017, 20, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.L.; Saade, D.R.; Greenough, P.G. Gender-based vulnerability: Combining Pareto ranking and spatial statistics to model gender-based vulnerability in Rohingya refugee settlements in Bangladesh. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2020, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Population Review. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospect 2019. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Mwenyango, H. The place of social work in improving access to health services among refugees: A case study of Nakivale settlement, Uganda. Int. Soc. Work. 2020, 8, 0020872820962195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavent, M. How to Use the PCAmixdata Package. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/PCAmixdata/vignettes/PCAmixdata.html (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- UN. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Goals and Targets (from the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development) Indicators 2020. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global%20Indicator%20Framework%20after%202021%20refinement_Eng.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Dagdeviren, H.; Van Der Hoeven, R.; Weeks, J. Poverty Reduction with Growth and Redistribution. Dev. Chang. 2002, 33, 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John-Phaltang, S. (Ethnic Communities Council of Queensland and Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia). Personal communication. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Solar Cooker Offers Ray of Hope for Refugee Environment. By Jennifer Clark. 4 June 2004. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/news/latest/2004/6/40c08d4b4/solar-cooker-offers-ray-hope-refugee-environment.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Turner, S. Suspended Spaces—Contesting Sovereignties in a Refugee Camp. In Sovereign Bodies. Citizens, Migrants, and States in the Postcolonial World; Hansen, T.B., Stepputat, F., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).