Leftover Consumption as a Means of Food Waste Reduction in Public Space? Qualitative Insights from Online Discussions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Relevance of Food Wastage Reduction in Food Service Organizations

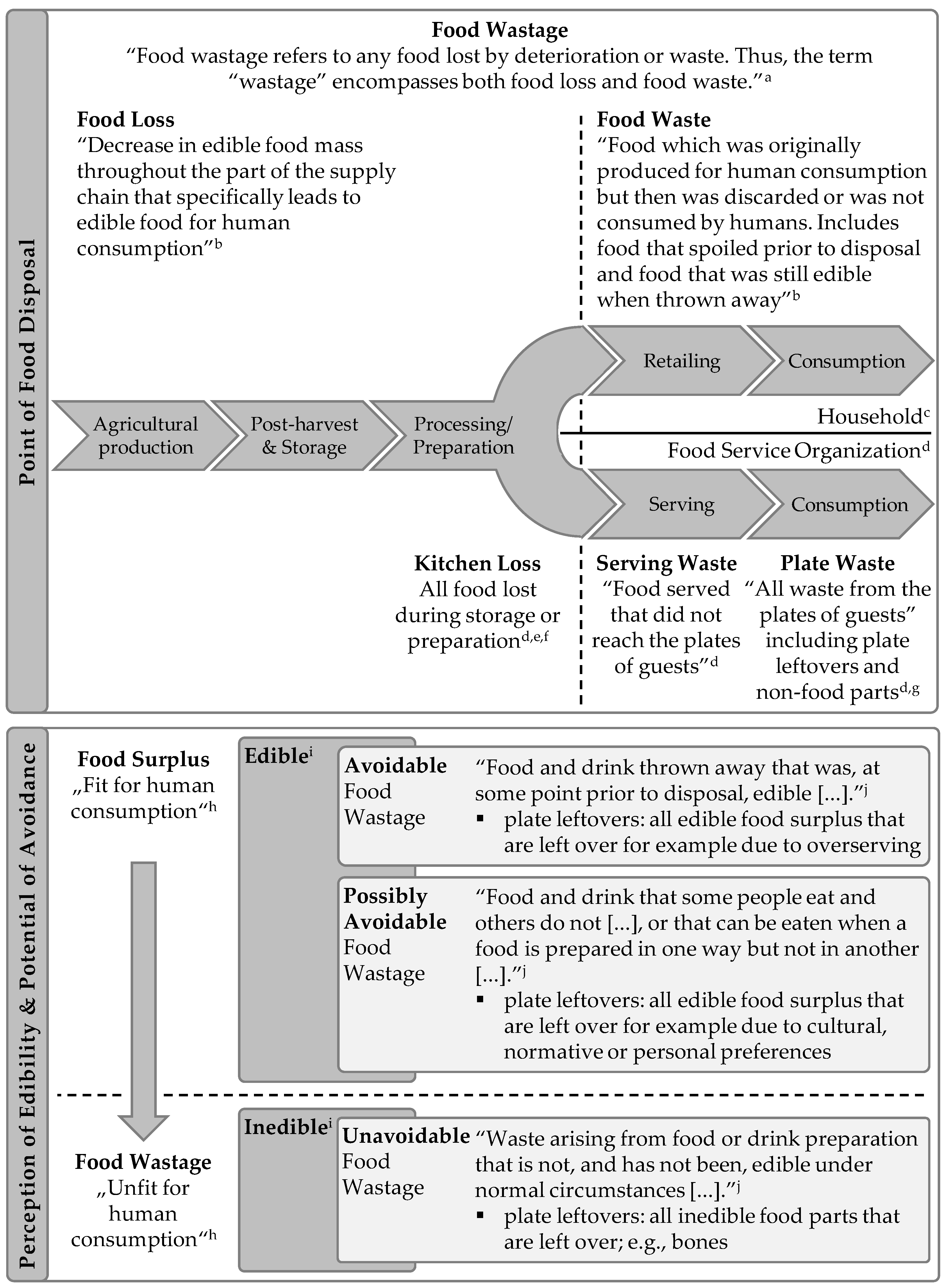

1.2. Conceptual Understanding of Food Wastage in Food Service Organizations

1.3. Consumer Movements Stressing the Reuse of Food Surplus

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Participants

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Analytical Process

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Attaining Physiological Needs through Satisfying Hunger

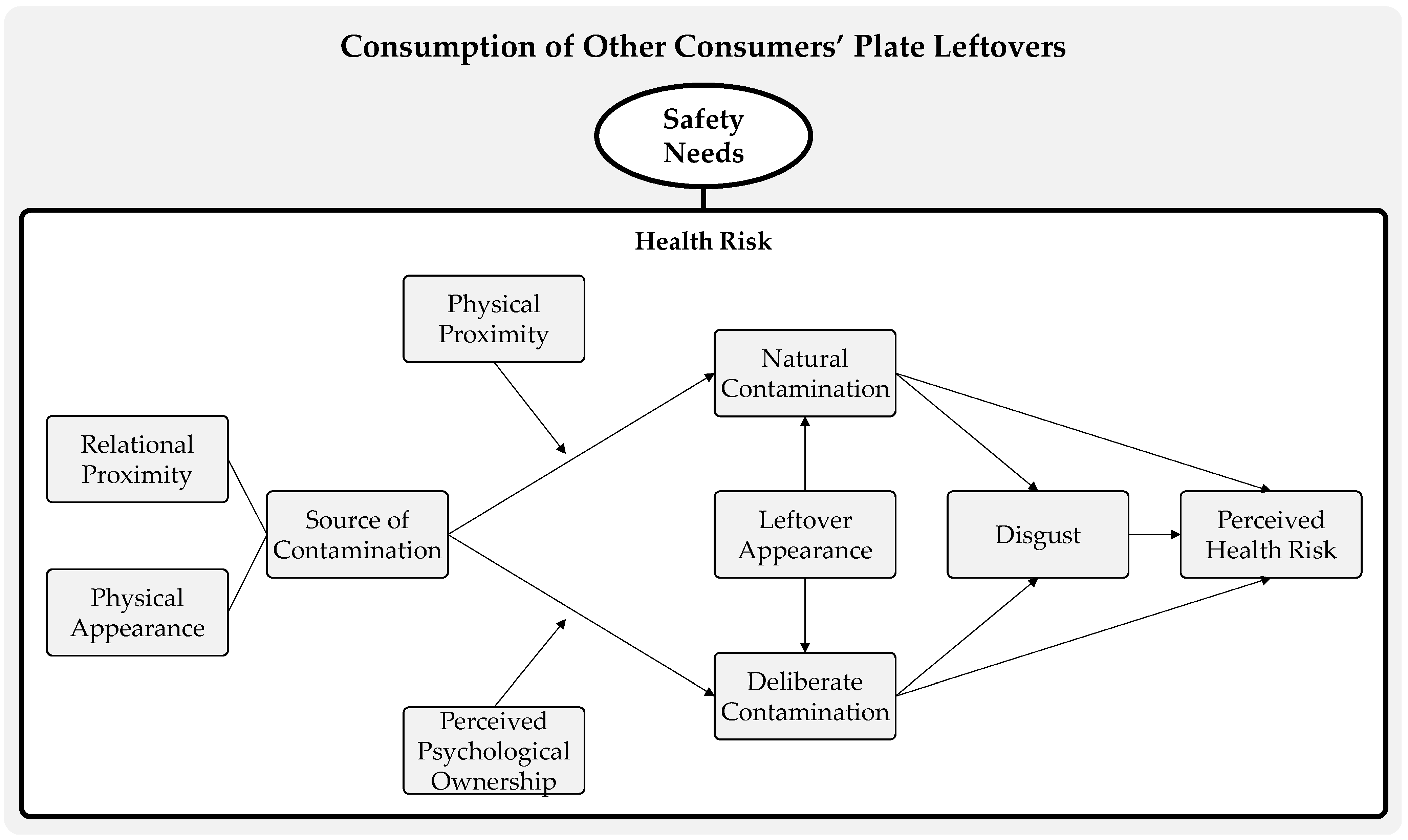

3.2. Attaining Safety Needs through the Protection of Individual Health and Social Order

3.3. Attaining Belongingness Needs through a Sense of Community

3.4. Attaining Esteem Needs through Gaining Attention and Protecting Self-Respect

3.5. Attaining Self-Actualization Needs through Idealism and Self-Transcendence Needs through Reducing Food Waste

3.6. Implications Based on the Associations with the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample

| Comments per Person | Total | News Media Site | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80.72% (875) | 75.20% (185) | 82.24% (690) |

| 2 | 10.52% (114) | 8.94% (22) | 10.97% (92) |

| 3 | 4.52% (49) | 6.10% (15) | 4.29% (36) |

| 4 | 1.75% (19) | 3.66% (9) | 1.19% (10) |

| 5 | 0.74% (8) | 1.63% (4) | 0.48% (4) |

| 6 | 0.37% (4) | 0.81% (2) | 0.12% (1) |

| 7 | 0.28% (3) | 0.41% (1) | 0.24% (2) |

| 8 | 0.46% (5) | 1.63% (4) | 0.12% (1) |

| … | … | … | … |

| 10 | 0.18% (2) | … | 0.24% (2) |

| … | … | … | … |

| 15 | 0.09% (1) | 0.41% (1) | … |

| … | … | … | … |

| 18 | 0.18% (2) | 0.41% (1) | 0.12% (1) |

| … | … | … | … |

| 23 | 0.09% (1) | 0.41% (1) | … |

| … | … | … | … |

| 34 | 0.09% (1) | 0.41% (1) | … |

| 100% (1084) | 100% (246) | 100% (839) |

Appendix B. Code System

| Inductive | Deductive | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Codes (Initial Codes) | Codes | Sub-Themes | Main Themes |

| Satisfying Hunger | Satisfying Hunger | Preventing Hunger through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers in Emergency Situation | Attaining Physiological Needs through Satisfying Hunger |

| Bändern for Monetary Reasons; Comparison/Distinction of Homelessness | Life Situation of the Consumer | ||

| Throwaway Society/Affluent Society | Socioeconomic Status of Residency | ||

| Poverty | Legitimization through Securing Existence | ||

| Unfair Behavior | Social Fairness | ||

| Health Risk; Diseases; Health Promotion | Perceived Health Risk | Perceiving Health Risk through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers | Attaining Safety Needs through the Protection of Individual Health and Social Order |

| Contamination Source; Hygiene | Natural Contamination | ||

| Modification of Leftovers | Deliberate Contamination | ||

| Disgust | Disgust | ||

| Leftover Appearance | Leftover Appearance | ||

| Partner; Family; Friends; Acquaintances; Work Colleagues; Strangers; Sympathy/Interpersonal | Relations Proximity to Contamination Source | ||

| Visual Appearance | Physical Appearance of Contamination Source | ||

| Eating Habits; Comparison/Distinction Physical Touching (Comparison/Distinction Kissing; Comparison/Distinction Sexual Activities); Comparison/Distinction Dumpster Diving | Physical Proximity to Contamination Source | ||

| Perceived Ownership; Entitlement to Leftovers No Longer Exists | Perceived Ownership of Plate Leftovers | ||

| Fundamental Criticism of the Legal Framework; Protection Mentality; Bureaucracy; Possession and Ownership Claims; Liability; Theft; House Rules/Domiciliary Right; Comparison/Distinction Legal Situations; Hygiene Regulations; Responsibility of the Bänderer; Responsibility of the Cafeteria | Legal Aspects | Creating Social Disorder through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers | |

| Economic Damage | Economic Damage for the Health Care System | ||

| Harm from Bändern; Subsidizing the Cafeteria; Cost Benefit from Ribboning; Profit-Orientation of the Cafeteria | Private Sector Damage | ||

| Skepticism Toward Leftovers; Unpleasant; Alienating; Undignified; Contradicts Rules/Norms/Codes of Conduct | Social Norm of Eating Culture | ||

| Dissemination of the Phenomenon “Bändern“ | Prevalence of the Behavior | ||

| Making Friends; Sense of Community | Being Part of a Community | Experiencing a Sense of Community through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers | Attaining Belongingness Needs through a Sense of Community |

| Differentiation from Others (In-group/Outgroup) | Experience of Exclusion | ||

| Protest; Rebellion | Gaining Individual Attention | Seeking Attention through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers | Attaining Esteem Needs through Gaining Attention and Protecting Self-Respect |

| Wanting to Prove Something/Putting Yourself on Display | Demonstrating Values | ||

| Shame | Losing Self-Respect | Threatening Self-Respect through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers | |

| Pride | Gaining Respect from the Community | ||

| Idealism/Moralism | Strengthening Idealism | Pursuing Idealism through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers | Attaining Self-Actualization Needs through Idealism and Self-Transcendence Needs through Reducing Food Waste |

| Do-gooder; Unrealistic | Do-Gooder | ||

| Inconsistent Behavior; Hypocrisy; Self-Enhancement; Conscience Calming; | Self-Elevation | ||

| Personal Enrichment | Freeloader | ||

| Neutral View Food Wastage; Problem Clarification Food Wastage; Problem Negation Food Wastage | Understanding Food Wastage/Food Wastage Consequences | “Saving the World” through the Consumption of Other Consumers’ Plate Leftovers | |

| Reduce/Prevent Food Wastage | Reducing Social and/or Environmental Impact | ||

| Create Attention/Awareness; Be a Role Model; Bring About Behavior Change | Helping Others to Reduce Food Wastage | ||

| Prohibition of Bändern; Interventions Against Bändern; Other Destructive Reactions | Prevention of Bändern (by the Canteen) | Interventions to Encourage or Discourage Consumption of Other Consumers’ Food Leftovers | |

| Refusal to Allow Access to Leftovers; Other Destructive Responses | Prevention of Bändern (by Consumers) | ||

| Bänderer Fee; Bänderer Contract; Signs; FairTeiler for Leftovers; Leftover Exchange Table; Provide Microwaves; Other Solutions | Support for Bändern (by the Canteen) | ||

| Passing on Leftovers Directly to Bänderer; Direct Approach; Bänderer Ribbon (Obvious Identifier of Sharing Interest); Other Solutions | Support for Bändern (by Consumers) | ||

| Adjust Portion Sizes; Offer Buffet Style/Pay by Weight; Adjust Pricing Policy; Improve Quality (Taste/Appearance); Analyze Leftovers; Adjust Production; Donate Food/Leftovers; Other Solutions | Prevention of Plate Leftovers (by the Canteen) | ||

| Cooking for Yourself; Assessing Your Own Hunger; Putting Less on Your Plate; Using Second Helpings, Emptying Your Plate; Education/Training on Handling of Food | Prevention of Plate Leftovers (by Consumer) | ||

| Reuse of Excess Ingredients; Reuse of Excess Dishes; Reuse of Leftovers | Alternative Reuse Options for Plate Leftovers (by the Canteen) | ||

| Sharing Food Before Eating; Having Leftovers Wrapped/Packaged; Taking Leftovers for Pets | Alternative Reuse Options for Plate Leftovers (by Consumers) | ||

References

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Stenmarck, Å.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels; FUSION: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; Available online: www.eu-fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/Estimates%20of%20European%20food%20waste%20levels.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Beretta, C.; Stoessel, F.; Baier, U.; Hellweg, S. Quantifying food losses and the potential for reduction in Switzerland. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WRAP. Food Surplus and Waste in the UK: Key Facts; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2021; Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/resources/report/food-surplus-and-waste-uk-key-facts (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Schmidt, T.; Schneider, F.; Leverenz, D.; Hafner, G. Food Waste in Germany—Baseline 2015—Summary Thünen Report 71. Available online: www.thuenen.de/media/institute/lr/Startseite_Aktuelles/baseline_summary_190916.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- forsa Politik-und Sozialforschung GmbH. Ernährungsreport 2019/2020: Ergebnisse Einer Repräsentativen Bevölkerungsbefragung; forsa Politik-und Sozialforschung GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Available online: www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/_Ernaehrung/forsa-ernaehrungsreport-2020-tabellen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Xue, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Cheng, G.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Dou, Z.; Cheng, S.; Liu, G. China’s food loss and waste embodies increasing environmental impacts. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malefors, C.; Callewaert, P.; Hansson, P.-A.; Hartikainen, H.; Pietiläinen, O.; Strid, I.; Strotmann, C.; Eriksson, M. Towards a Baseline for Food-Waste Quantification in the Hospitality Sector—Quantities and Data Processing Criteria. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A. Opening the black box of food waste reduction. Food Policy 2014, 46, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvennoinen, K.; Nisonen, S.; Pietiläinen, O. Food waste case study and monitoring developing in Finnish food services. Waste Manag. 2019, 97, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, A.; Buchli, J.; Göbel, C.; Müller, C. Food waste in the Swiss food service industry—Magnitude and potential for reduction. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, S. Understanding out of Home Consumer Food Waste; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2013; Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-08/understanding-out-of-home-consumer-food-waste.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Lorenz, B.A.; Hartmann, M.; Langen, N. What makes people leave their food? The interaction of personal and situational factors leading to plate leftovers in canteens. Appetite 2017, 116, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derqui, B.; Fernandez, V.; Fayos, T. Towards more sustainable food systems. Addressing food waste at school canteens. Appetite 2018, 129, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, R.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Food losses in food service institutions: Examples from Sweden. Food Policy 2004, 29, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; Lozano, R.; Padfield, R.; Ujang, Z. Patterns and Causes of Food Waste in the Hospitality and Food Service Sector: Food Waste Prevention Insights from Malaysia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silvennoinen, K.; Heikkilä, L.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Reinikainen, A. Food waste volume and origin: Case studies in the Finnish food service sector. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020: Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9692en/ (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Smil, V. Improving Efficiency and Reducing Waste in Our Food System. Environ. Sci. 2004, 1, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3347e/i3347e.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Full-Cost Accounting; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3991e/i3991e.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- United Nations Headquarters. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations Headquarters: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Boulet, M.; Hoek, A.C.; Raven, R. Towards a multi-level framework of household food waste and consumer behaviour: Untangling spaghetti soup. Appetite 2021, 156, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzby, J.C.; Hyman, J. Total and per capita value of food loss in the United States. Food Policy 2012, 37, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUSION. FUSIONS Definitional Framework for Food Waste; FUSION: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014; Available online: www.eu-fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/FUSIONS%20Definitional%20Framework%20for%20Food%20Waste%202014.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Lebersorger, S.; Schneider, F. Discussion on the methodology for determining food waste in household waste composition studies. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodhuyzen, D.M.A.; Luning, P.A.; Fogliano, V.; Steenbekkers, L.P. Putting together the puzzle of consumer food waste: Towards an integral perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quested, T.; Johnson, H. Household Food and Drink Waste in the UK; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2009; Available online: www.wrap.org.uk/resources/report/household-food-and-drink-waste-uk-2009 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Koivupuro, H.-K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G.; Parente, J.; Wansink, B. Food waste paradox: Antecedents of food disposal in low income households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osner, R. Food Wastage. Nutr. Food Sci. 1982, 82, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMEL. Das Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft Informiert zu Möglichkeiten der Mitnahme Nicht Verzehrter Speisen; Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft: Berlin, Germany, 2019; Available online: www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2019/082-speisenmitnahme.html;jsessionid=A40D9C46CAAFA1E50035A2C292736431.live921 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.; Kerr, G.; Pearson, D.; Mirosa, M. The attributes of leftovers and higher-order personal values. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1965–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, L.S.; Lipton, K.; Manchester, A.; Oliveira, V. Estimating and Addressing America’s Food Losses. Food Rev. 1997, 20, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellini, B. The sacrifice of re-use: The travels of leftovers and family relations. J. Consum. Behav. 2009, 8, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teigiserova, D.A.; Hamelin, L.; Thomsen, M. Towards transparent valorization of food surplus, waste and loss: Clarifying definitions, food waste hierarchy, and role in the circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 136033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleemann, B. Stadtgespräch|“Bändern” gegen Essen im Müll: Euer Garbage, unser Life; detektor.fm: Leipzig, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://detektor.fm/gesellschaft/stadtgespraech-baendern-gegen-essen-im-muell (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Gollnhofer, J.F.; Weijo, H.A.; Schouten, J.W. Consumer Movements and Value Regimes: Fighting Food Waste in Germany by Building Alternative Object Pathways. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board of foodsharing e.V. Lebensmittel Retten Wiki: Kontext und Selbstverständnis. In Stadtgespräch|“Bändern” gegen Essen im Müll: Euer Garbage, unser Life; Foodsharing e.V.: Köln, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://wiki.foodsharing.de/Kontext_und_Selbstverst%C3%A4ndnis (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. EU Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32002R0178&from=EN (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Rombach, M.; Bitsch, V. Food Movements in Germany: Slow Food, Food Sharing, and Dumpster Diving. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schanes, K.; Stagl, S. Food waste fighters: What motivates people to engage in food sharing? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, K.V.; Brittain, A.J.; Bennett, S.D. “Doing the duck”: Negotiating the resistant-consumer identity. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 1779–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganglebauer, E.; Fitzpatrick, G.; Subasi, Ö.; Güldenpfenning, F. Think Globally, Act Locally: A Case Study of a Free Food Sharing Community and Social Networking. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–19 February 2014; pp. 911–921. [Google Scholar]

- Morone, P.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, A. Does food sharing lead to food waste reduction? An experimental analysis to assess challenges and opportunities of a new consumption model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazell, J. Consumer food waste behaviour in universities: Sharing as a means of prevention. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.M.; Wardle, J. Development of a Measure of the Motives Underlying the Selection of Food: The Food Choice Questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, L.; Rozin, P.; Fiske, A.P. Food sharing and feeding another person suggest intimacy; two studies of American college students. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshaiwi, A.; Harries, T. A step in the journey to food waste: How and why mealtime surpluses become unwanted. Appetite 2021, 158, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, B.; Parsons, E. Sharing the Meal: Food Consumption and Family Identity. Res. Consum. Behav. 2012, 14, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhmer, M.M.; Buchholz, U.; Corman, V.M.; Hoch, M.; Katz, K.; Marosevic, D.V.; Böhm, S.; Woudenberg, T.; Ackermann, N.; Konrad, R.; et al. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak in Germany resulting from a single travel-associated primary case: A case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsham, G. Doing interpretive research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G.; Wyatt, J.C. Facilitating research. In Medicine and the Internet: Introducing Online Resources and Terminology, 3rd ed.; McKenzie, B.C., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, D. Online Discussion Forums: A Rich and Vibrant Source of Data. In Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques; Braun, V., Clarke, V., Gray, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Berger, J. When, Why, and How Controversy Causes Conversation. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hille, S.; Bakker, P. Engaging the social news user: Comments on news sites and Facebook. Journal. Pract. 2014, 8, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The British Psychological Society. Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research; Leicester University Press: London, UK, 2017; Available online: www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/ethics-guidelines-internet-mediated-research-2017 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA: Text, Audio, and Video; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. The Instinctoid Nature of Basic Needs. J. Personal. 1954, 22, 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koltko-Rivera, M.E. Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2006, 10, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality, 2nd ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Wahba, M.A.; Bridwell, L.G. Maslow Reconsidered: A Review of Research on the Need Hierarchy Theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 15, 212–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neher, A. Maslow’s Theory of Motivation: A Critique. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1991, 31, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.; Diener, E. Needs and Subjective Well-Being Around the World. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, G.P. Nutrition: Maintaining and Improving Health, 5th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gollnhofer, J.F.; Hellwig, K.; Morhart, F. Fair Is Good, but What Is Fair? Negotiations of Distributive Justice in an Emerging Nonmonetary Sharing Model. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Food Safety: Data by WHO Region; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.IHRREG11v?lang=en (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Nemeroff, C.; Rozin, P. Back in Touch with Contagion: Some Essential Issues. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2018, 3, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. The State of Psychological Ownership: Integrating and Extending a Century of Research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J.J.; Dahl, D.W.; Morales, A.C. Consumer Contamination: How Consumers React to Products Touched by Others. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angyal, A. Disgust and related aversions. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1941, 36, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P. Individual Differences in Sensitivity to Disgust: A Scale Sampling Seven Domains of Disgust Elicitors. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1994, 16, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egolf, A.; Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. How people’s food disgust sensitivity shapes their eating and food behaviour. Appetite 2018, 127, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.C.; Dahl, D.W.; Argo, J.J. Amending the Law of Contagion: A General Theory of Property Transference. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2018, 3, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Siemers, E.; Teran, V.; Conroy, R.; Lankford, M.; Agrafiotis, A.; Ambrose, L.; Locher, P. Neatness counts. How plating affects liking for the taste of food. Appetite 2011, 57, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zellner, D.A.; Loss, C.R.; Zearfoss, J.; Remolina, S. It tastes as good as it looks! The effect of food presentation on liking for the flavor of food. Appetite 2014, 77, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J.J.; Dahl, D.W.; Morales, A.C. Positive Consumer Contagion: Responses to Attractive Others in a Retail Context. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Haidt, J.; McCauley, C.R. Disgust. In Handbook of Emotions, 3rd ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Barrett, L.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 757–776. [Google Scholar]

- Balaam, B.J.; Haslam, S.A. A Closer Look at the Role of Social Influence in the Development of Attitudes to Eating. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 8, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kniazeva, M.; Venkatesh, A. Food for thought: A study of food consumption in postmodern US culture. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sebbane, M.; Costa, S. Food leftovers in workplace cafeterias: An exploratory analysis of stated behavior and actual behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.L.; Truant, P.L. Wasted Food: U.S. Consumers’ Reported Awareness, Attitudes, and Behaviors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L.; Carlsmith, J.M. Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1959, 58, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kallbekken, S.; Sælen, H. ‘Nudging’ hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Econ. Lett. 2013, 119, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosa, M.; Liu, Y.; Mirosa, R. Consumers’ Behaviors and Attitudes toward Doggy Bags: Identifying Barriers and Benefits to Promoting Behavior Change. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 563–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Lála, J.; Kocmanová, K. Understanding the antecedents of consumers’ attitudes towards doggy bags in restaurants: Concern about food waste, culture, norms and emotions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerman, E.J.; Rudell, F.; Martins, C.M. Factors that predict taking restaurant leftovers: Strategies for reducing food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero Waste Europe. France’s Law for Fighting Food Waste: Food Waste Prevention Legislation; Zero Waste Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://zerowasteeurope.eu/library/france-law-for-fighting-food-waste/ (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Chazan, D. ‘Doggy Bag’ Law Introduced in France; The Telegraph Online: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/12079039/Doggy-bag-law-introduced-in-France.html (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F. Environmental impact of packaging and food losses in a life cycle perspective: A comparative analysis of five food items. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvenius, F.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Grönman, K.; Soukka, R.; Koivupuro, H.-K.; Virtanen, Y. Role of packaging in LCA of food products. In Towards Life Cycle Sustainability Management; Finkbeiner, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, B.J. A behavior model for persuasive design. In Persuasive ’09: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Claremont, CA, USA, 26–29 April 2009; Chatterjee, S., Dev, P., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, B.J. Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything; Virgin Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Ogarca, R.F.; Barbu, C.M.; Craciun, L.; Baloi, I.C.; Mihai, L.S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food waste behaviour of young people. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocol, C.B.; Pinoteau, M.; Amuza, A.; Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Glogovețan, A.-I. Food waste behavior among Romanian consumers: A cluster analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Dumpster Diving | Foodsharing | Bändern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | “Dumpster diving involves entering a commercial or residential dumpster […] to retrieve rubbish.” [48] (p. 1779) | “Foodsharing […] is a community platform in Germany that enables consumers, farmers, organizations and retailers to offer and collect food articles to save them from being wasted” [49] (p. 912) | Bänderer purposefully choose to eat other consumers’ plate leftovers instead of buying fresh meals. |

| Food Waste Hierarchy Option | Reuse | Reuse | Reuse |

| Consumption Context | Private (Household) | Private (Household) | Public (Food Service) |

| Time of Food “Rescue” |  |  |  |

| Type of “Rescued” Food | Surplus Food | Surplus Food | Plate Leftovers |

| Compliance with German Legal Requirements | Contempt of Legal Requirements | Following Legal Requirements | Legal Grey Area |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diekmann, L.; Germelmann, C.C. Leftover Consumption as a Means of Food Waste Reduction in Public Space? Qualitative Insights from Online Discussions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413564

Diekmann L, Germelmann CC. Leftover Consumption as a Means of Food Waste Reduction in Public Space? Qualitative Insights from Online Discussions. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413564

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiekmann, Larissa, and Claas Christian Germelmann. 2021. "Leftover Consumption as a Means of Food Waste Reduction in Public Space? Qualitative Insights from Online Discussions" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413564

APA StyleDiekmann, L., & Germelmann, C. C. (2021). Leftover Consumption as a Means of Food Waste Reduction in Public Space? Qualitative Insights from Online Discussions. Sustainability, 13(24), 13564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413564