Guidelines for Citizen Engagement and the Co-Creation of Nature-Based Solutions: Living Knowledge in the URBiNAT Project

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Input on Citizen Engagement

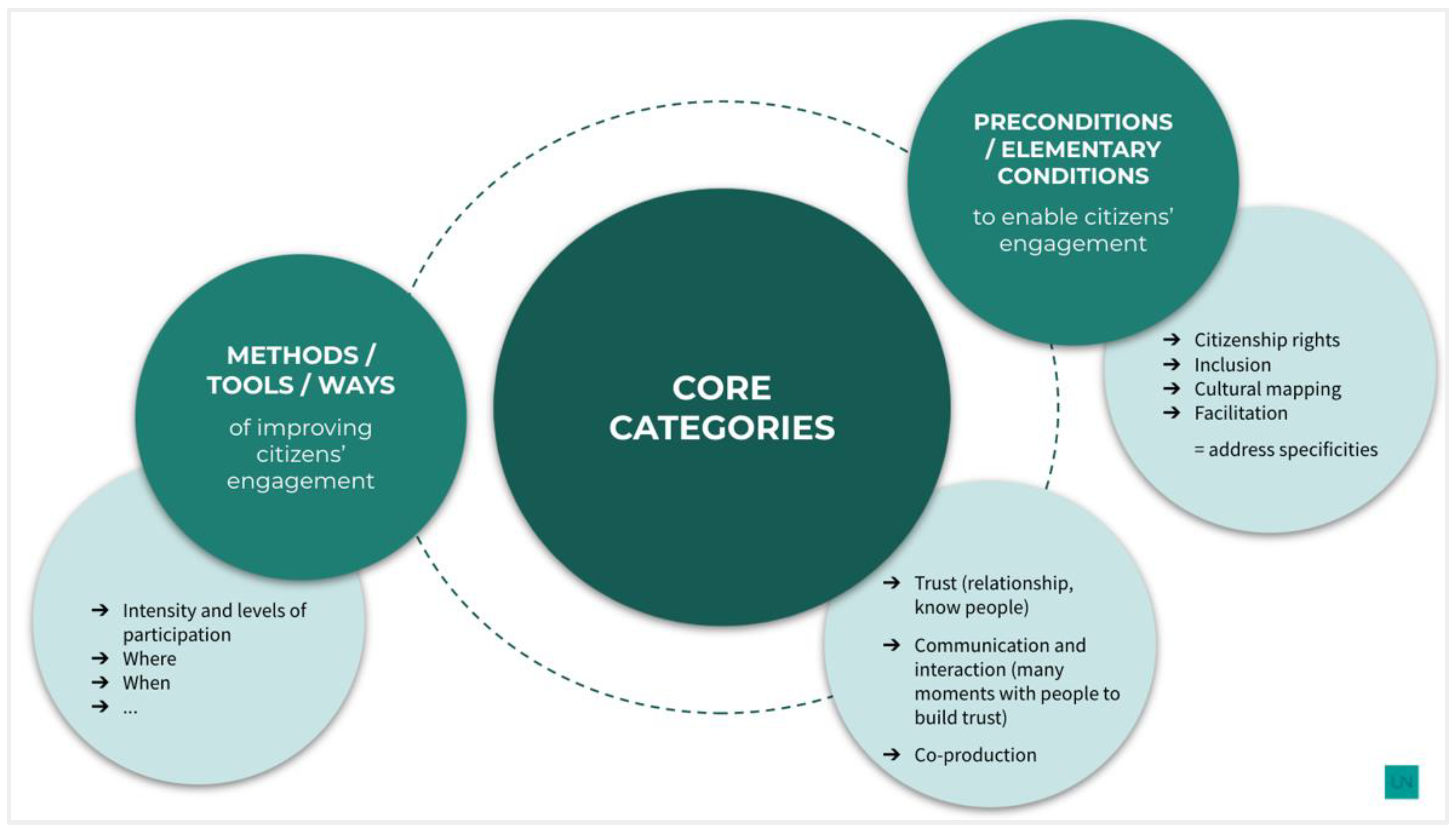

2.2. Systematization into Categories of Significant Factors Impacting Citizen Engagement

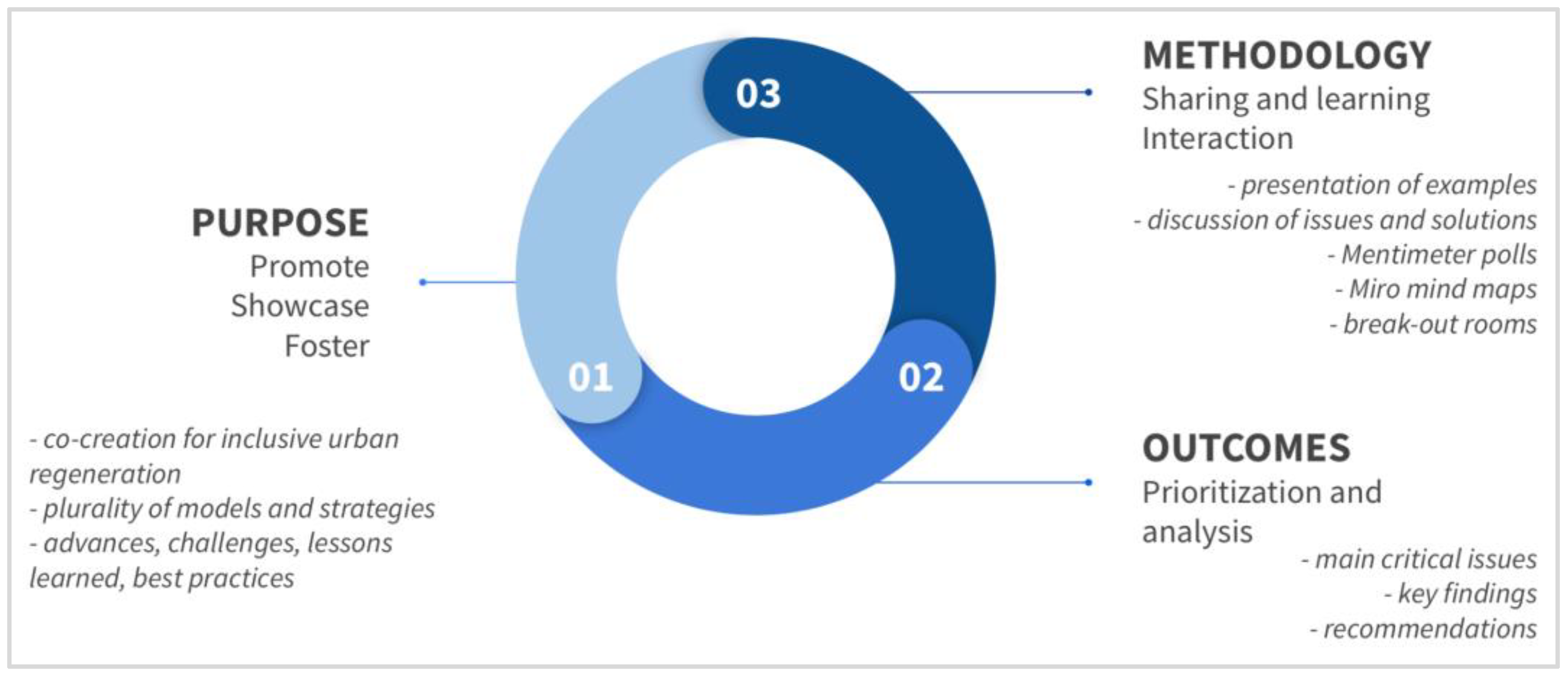

2.3. Sharing and Learning with Practitioners from the Field, Inside and Outside URBiNAT, towards Living Knowledge

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Guideline Categories for Citizen Engagement

- At the top of the ranking are: (1) Communication and interaction (16% of participants suggested this category), (2) Behavioural changes (14%), and (3) Trust (12%);

- In the intermediate position are: (4) Co-production (10%), (5) Inclusion (9%), as well as visions and priorities, i.e., Regulation (9%), and (6) Governance (8%);

- The lowest ranking categories include: (7) Innovation cycle (6%), (8) Transparency (5%), as well as the levels and conditions of participation, i.e., Intensity and levels of participation (5%), (9) Citizenship rights (4%), and (10) Cultural mapping (2%);

- Categories not scored/prioritized by participants include: Facilitation, Quality of deliberation, Where, When, Supportive methodologies and techniques, Integration of the results of participatory processes, Private sector, and Monitoring and evaluation.

3.2. Relevance and Added Value of ‘Living’ Guidelines for Citizen Engagement and NBS Co-Creation

3.3. Emerging Learning Points in Relation to NBS Co-Creation

- NBS that are aesthetically, socially, economically, and charitably appealing to citizens and stakeholders;

- New urban spaces where people with common interests can regularly gather and engage;

- NBS diagnostics, design, and implementation relying on a community of stakeholders;

- Strong common projects between actors with different organisational goals as the propellers of social innovation;

- Inclusive and multistakeholder governance as a result of a collaborative approach;

- Bridging differences through an inclusive and highly attractive narrative;

- Effectiveness, achievements, scaling up, and replication as a result of monitoring and evaluation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Working Interdisciplinary and Interculturally in Developing NBS

4.2. Rethinking Engagement, Especially in Times of COVID-19

4.3. Sharpening Participation for an Inclusive and Innovative Urban Regeneration with NBS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category of Guidelines 1 | Prioritization 2 | Strategic Overview | Operational Details | Impact of Other Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication and interaction | 1 | Communicating specificities for interacting with citizens. | Covers, in operational terms: (1) Communication strategies; (2) Communication materials and channels; (3) Multichannel interaction; (4) Codes of conduct related to communication and ethics. | This category ties in with the category of Trust, especially with regard to how communication and interaction with residents happens. For instance, depending on the city, building trust may be based on meetings and face-to-face encounters, whereas the use of digital tools is limited and aimed at incentivising being together. Social circles of residents may also be limited to close relatives, which enhances the importance of providing a space where people can communicate and not be frightened of being together. Furthermore, organisations working with specificities constitute important partners in establishing communication and interaction with particular groups and individuals. |

| Behavioural changes | 2 | Instigating behavioural adjustments, or changes in behaviour, in some particular respect. | Namely, by: (1) Challenging traditional models of governance, expert advice, and implementation; and (2) Instigating adjustments to attitudes, mindsets, and behaviours in support of participation and collaboration. | Ties in with the category of Communication and interaction in many ways, including: how residents are shown that their inputs are valuable and can be applied for the creation of change; identifying and engaging agents of change; promoting participatory and creative activities to address specific behaviours (e.g., aggression, intolerance, lack of openness, and looking at the different cultures and existing boundaries built on the differences). |

| Trust | 3 | Improving or creating relationships of trust between citizens, and between citizens and city staff, politicians, and other agents. | With particular attention to: (1) Confidence and team dynamics; and (2) Language. | Ties in with the categories of Transparency, Inclusion, Communication and interaction, and Governance by: ensuring that everyone is part of the conversation and deliberations; documenting the activities to promote ownership; qualifying local ideas instead of bringing many ideas from practitioners/experts; properly communicating and translating what the residents feel, as well as repeating people’s opinions. It also ties in with the categories of Culture of participation and Cultural mapping since, as highlighted by practitioners from the field in URBiNAT cities, Trust and Transparency may impact citizen engagement to a greater extent according to the local context. This is the case of contexts marked by distrust or a history of failure and disappointment, which require the exploration of different mechanisms [71]. |

| Co-production | 4 | Stimulating and improving the co-production of public services, participatory processes, and product development. | Focusing in particular on: (1) The process by which citizens participate in the implementation and delivery phase; (2) An open process of participation that includes a wide range of key actors, namely, end-users. | Ties in with the categories of Trust and Behavioural change, in particular relative to team dynamics at the different stages of the NBS co-creation process, and by challenging traditional models of implementation. |

| Inclusion | 5 | Having specific guidelines to guarantee the inclusion of diversity. | Concerning: (1) The different modalities of the participatory process; (2) Not only pursuing the ‘usual suspects’ who always participate and are more engaged because of their availability, resources, and professional/disciplinary skills, and may also constitute an exclusive group; (3) Capacity and tools to address and welcome diversity. | Ties in with the categories of Citizenship rights, Governance, Transparency, and Regulation, given that inclusion must be shown through bonds and by sticking together (e.g., the scene is the house for volunteer associations where they can bring more people). It also ties in with the category of Supportive methodologies and techniques in terms of the modalities for mobilization and inclusivity in the participatory process. |

| Regulation | 5 | Clarifying rules and regulations for equal rights in the expression of visions and priorities. | It means not only to: (1) Establish rules and regulations for the participatory process; but also (2) Promote co-decisional processes. | Tying in with the categories of Governance, Transparency, and Trust, the local contexts may bring additional critical issues, such as when rules are not followed. |

| Governance | 6 | Balancing interactions among citizens, city staff, politicians, and other agents. | The Governance category focuses on: (1) Opening doors in the public sphere and balancing power relations; (2) More liveable and balanced interactions; (3) Organization of participation in an integrated manner, going beyond the institutional division of municipal departments. | It ties in with the categories of Trust, Transparency, and Culture of participation. The use of Participatory NBS is particularly relevant in this respect, by promoting participatory activities that improve collaboration and empower individuals in the decision-making process. |

| Innovation cycle | 7 | Adopting processes of rupture and searching for alternative solutions to address concrete social problems. | By: (1) Breaking the crystallized image of a problematic neighbourhood, including observing a code of conduct for the communication and dissemination of activities; (2) Connecting people, introducing creativity, and mobilizing energy. | The use of Participatory NBS is relevant in promoting such an innovation cycle when they focus on the available resources, assets, and relationships of solidarity in the community. Ties in with the category of Citizenship rights relative to strengthening the capabilities and empowerment of the population as well as the satisfaction of needs and the corresponding access to rights. |

| Transparency | 8 | Arguments for encouraging efforts to act in a transparent manner. | With an emphasis on: (1) Reflecting on why people should participate in the process, and being clear about purposes and rules; (2) Avoiding hidden agendas or information. | Ties in, to a great extent, with the categories of Trust and Governance. When there is a lack of trust between citizens and politicians, transparency is even more necessary from the municipality as a governance issue to build trust. It also ties in with the categories Why participation and Monitoring and evaluation, given the need to provide information enable discussion of the results of each stage, and to include a systematic follow-up. This means being able to speak about expected results that are both positive and negative, and to give feedback about what is going well and what is not, which will impact expectations and trust. |

| Intensity and levels of participation | 8 | Setting different approaches and levels of participation depending on the goals and real conditions for participation. | Through: (1) Systematic awareness of the conditions under which citizens are prepared to engage in actions of social innovation; and (2) Thinking about different steps to citizen engagement (e.g., communication, information, consultation, participation, co-building). | Ties in with the Culture of participation category, which can reveal strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in interaction and will guide the design of participatory processes. To be community-driven, the design must focus on raising the intensity of interactions among citizens, stakeholders, organizations, and institutions. |

| Citizenship rights | 9 | Broadening the meaning of the appropriation of social, urban, political, and cultural rights, both internally in the collective imagination, and externally in rejuvenated relationships with local powers. | In operational terms, the emphasis would be on addressing: (1) Access to and implementation of rights; (2) Engaging/empowering; (3) Strategies designed to promote participation according to specificities; (4) Codes of conduct related to research and ethics. | Ties in with the category of Inclusion, namely, concerning the modalities of the participatory process which addresses, welcomes, and promotes diversity. The use of Participatory NBS, such as Forum Theatre, is relevant in this respect in that it involves the community in the analysis and discussion of problems, thereby raising awareness and encouraging citizen participation. |

| Cultural mapping | 10 | Articulating and making visible the multilayered cultural assets, aspects and meanings of a place. | It: (1) Encourages the attachment of citizens to a location; and (2) Acts as a catalyst to the process. | Tying in with the category of Inclusion and more than simply just another tool, cultural mapping is relevant if used as an approach to get to know people, address their specificities, what they like to do, and what they want to do, as used in the co-diagnostic phase of the URBiNAT co-creation process. It also ties in with the categories of Innovation cycle and Supportive methodologies and techniques as a Participatory NBS, since cultural mapping emphasizes processes that enable projects to be platforms for discussion, engagement, and empowerment. |

| Facilitation | - | Having specific guidelines to address facilitation that include other participatory guidelines. | Defining: (1) The main attributes of facilitation in understanding the role that is expected; (2) The different steps of the co-creation process, including information about NBS; (3) How to hold successful public meetings based, for example, on successful participatory cases; (4) The principles and requirements of ethics. | These aspects need to be covered in guidelines, training of local facilitators, and corresponding support materials. Participatory NBS, such as Learning for Life or community workshops, constitute useful resources to help organize these aspects and put them into practice, by providing protocols and approaches that will support facilitation. This category, therefore, ties in with the category of Supportive methodologies and techniques. |

| Quality of deliberation | - | Setting a meaningful deliberation process. | Through: (1) Authentic deliberation; (2) A clear decision-making process; and (3) Ensuring equal rights of expression. | More than simply voting, the focus is on interaction, democratic decisions, and expression, which ties this category in with the categories of Regulation, Governance, Citizenship rights, and Facilitation. |

| Where | - | Having guidelines for the spaces in which the participatory events are held. | Addressing: (1) Place/setting: as well as (2) Form and quality. | Ties in with the categories of Communication and interaction and Facilitation since the definition of these aspects is all the more relevant when dealing with a lack of space in which to speak and do things together. Spaces to not ony share visions, values, roles, dialogue with people, but also to create a dialogue between people. For example, older adults and victims of violence need to be heard in a space where they can voice what they want to do and what they need. Determination of how to devise a model for a space that incentivises people to work constructively together is key. |

| When | - | Identifying the best moment for the participatory events. | Including: (1) Time/day; (2) Date; and (3) Phase. | In practical terms, this category implies meeting the community and knowing as much as possible about the needs of the people who live in the area of intervention, as well as their habits and traditions, so that the participatory activities can be tailored to fit. Additionally, to be relevant, participation cannot happen at the end of the process of planning a project. Ideally, we should all begin together, with an empty page or question to be addressed, but it depends on the project, on whether it has already started, and on its technical level. What needs to be assessed is the decision on the right time/phase to engage. Therefore, this ties in with the categories of Communication and interaction and Facilitation. |

| Supportive methodologies and techniques | - | Using specific methodologies and guidelines to support mobilization and inclusivity. | Considering: (1) Culture as a platform; (2) Lower degrees of formalization; and (3) Articulation of knowledge. | Ties in particularly with the categories of Communication and interaction, Facilitation, and Cultural mapping. Generally speaking, in practical terms, arts and community events can facilitate creativity. We can also consider here the appropriation of complex languages by including people’s knowledge in dialogue with technical and scientific knowledge. Going beyond Cultural Mapping, Forum Theatre, or community-based art, which makes specific use of the arts, Participatory NBS comprise protocols, approaches, and methods aimed at engaging citizens at different stages of the co-creation process. |

| Integration of the results of participatory processes | - | Enlarging the scope of co-creation to validate the ideas developed. | Through: (1) Cross-pollination; (2) Validation; (3) Systematization; and (4) Definition of purpose. | This ties in particularly well with the categories of Communication and interaction, Facilitation, and Supportive methodologies and techniques, concerning the use of communication materials and channels, the definition of the different steps of the co-creation process, and with the articulation of knowledge from people, technicians, experts, and researchers. |

| Private sector | - | Mapping the relevant private sector actors with interests in, and input to, the NBS targeted area. | Requires: (1) Mapping who has links and can facilitate contacts with private actors (e.g., business associations, local companies, private owners), as well as their eventual roles in the co-creation of NBS; (2) Conducting meetings and workshops with specific groups to understand visions, priorities, and interests, as well as bringing all participating groups together to devise a common vision and project, as well as to seek formal commitment. | Highlighted here is the definition of the relevance of the private sector, not limited to actors, among others. It ties in with the categories of Co-production and Innovation cycle relative to the development of products and services, the involvement of a wide range of key actors, and connecting them based on creativity and the mobilization of energy. |

| Monitoring and evaluation | - | Addresses monitoring and evaluation of the participatory process. | The aspects related to monitoring and evaluation of the participatory process cover: (1) The process itself; (2) Results and impact of participation; (3) The different aspects of evaluation guiding the selection of methods for impact assessment, taking into consideration: (4) Participatory monitoring and evaluation; as well as (5) Participatory impact assessment. | Ties in with the categories of Transparency in terms of information and follow-up, and Ownership of the co-creation process and the corresponding results. |

| Risk assessment and mitigation measures | - | Identifying the factors influencing co-creation processes, as well as those leading to the failure of co-creation and co-production. | In operational terms, it covers the identification of both: (1) Basic requirements in the risk assessment of co-creation processes; (2) Mitigation measures corresponding to risk factors related to the process of engaging citizens in co-creation and their participation in the implementation and delivery phase. | It ties in with the categories of Monitoring and evaluation and Transparency regarding clarity of the participatory process, its assessment, and improvement. |

| Ownership | - | Citizens having ownership of both problems and solutions. | This depends on: (1) The assumption that practitioners can only bring knowledge if people own the process, by providing the framework but not taking the lead; (2) Enabling inputs from people by showing that contribution is possible and providing safe spaces, as well as implementing a diversity of appealing activities. | This category, therefore, ties in with the categories of Trust and Communication and interaction. |

| Culture of participation | - | Enabling regular interaction with citizens, and increasing the culture of participation. | Requirements: (1) Transversally increasing the culture of participation in all departments of the municipality by introducing new models that involve all people and services, as well as building bridges between the public sector, the private sector, and citizens; (2) Enabling initiatives by citizens, with consideration given as to how to encourage, receive, and adapt to spontaneous initiatives that they make, and how to listen to and receive these initiatives, some of which will be off the municipal radar. | Ties in with the categories of Governance and Intensity and levels of participation, regarding interactions between city staff and citizens. |

| Why participation | - | Being clear as to why we need to engage citizens and support participatory processes. | Includes: (1) The object of participation, and the things we want to discuss and do with people; (2) The purpose of participation, why participation is important to the project in question, and what motivates people to participate; (3) Ways of carrying out participation, and why we use specific methodologies; (4) The relevance of participation, since not everything needs to be in the form of dialogue/discussion. Participation is not always the solution, and sometimes inputs can be received in other ways. | Ties in with the categories of Transparency and Intensity and levels of participation relative to the clarity of purpose and rules, as well as to the consideration of different approaches in accordance with the goals and real conditions of participation. |

| Mediation | - | Dialogue and collaboration. | Covering both: (1) The resolution of conflicts; and (2) The use of dialogue to foster collaboration between people who do not have much experience in this type of problem solving. | Ties in with the categories of Communication and interaction, Trust and Facilitation, concerning strategies that are sensitive to local history and existing relationships, to build trust and foster being/working together, as well as the specific attributes and expected role of the mediator. |

Appendix B

| Learning Points | Overview and Discussion | Examples of NBS Participatory Cases | Links of Learning Points/Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| The appeal of NBS to citizens and stakeholders aesthetically, socially, economically, and charitably. | NBS need to be aesthetically, socially, economically, and charitably appealing to citizens and stakeholders so that they are encouraged to engage with, further develop, maintain, and protect them. | A workshop was conducted at Høje-Taastrup (Denmark) in which huge planter boxes with flowers and berry bushes were co-created to provide an instant reward to co-creators and the inhabitants of the neighbourhood. | Why participation, Where and Integration of participatory process results. |

| NBS and new urban spaces where people with common interests can regularly gather and engage. | NBS create new urban collective spaces at the neighbourhood level and across the city. This is achieved both virtually, through online platforms, and physically, by creating attractive physical spaces where people with common interests can gather and engage on a regular basis, as part of their daily lives or for special events. | In Milan (Italy), a previously deprived neighbourhood was turned into an attractive neighbourhood through the online coordination of many different events and facilities, including local radio, breakfast meetings on street corners, and support for the opening of small shops and services. | Where, Innovation cycle, and Ownership. |

| Diagnostics, design, and implementation of NBS rely on a community of stakeholders. | For deprived neighbourhoods, NBS diagnostics, design (experiments), and implementation processes rely on and feed into trust, co-ownership, governance, and regulation between the five main stakeholders, identified as "participants" in the URBiNAT model [33]: (1) The municipality (political representatives and technicians of different departments); (2) Housing administrators (responsible for the management of social housing); (3) NGOs, businesses and other private and public organisations working in the intervention areas; (4) Champions/ambassadors and facilitators; and (5) Citizens, as well as in the experiments themselves. Several other factors also play a role depending on the characteristics of the neighbourhood and the NBS. | In Porto (Portugal), a task force made up of these five actors has been formed to coordinate and provide project governance to many experiments now being designed in the designated social neighbourhood. | Many of the guideline categories and especially Trust, Ownership, Governance, and Regulation. |

| Strong common projects between actors with different organisational goals as propellers of social innovation. | Sustainable NBS emerge strongly from the fabric of social innovation at the neighbourhood and urban levels, building success on the back of strong common projects between actors with different organisational goals (link to a sense of co-ownership). Social innovation is referred to here as a process, implying changes in social relations and power relations, or as a product, by means of the construction of methodologies, artifacts, and/or services, especially those aimed at strengthening the capabilities of the population, the satisfaction of needs, and the access to rights [103,104,105,106]. | In Nantes (France), facilities and activities are emerging through social innovation along a green path that connects the deprived neighbourhood with the rest of the city. Pre-existing citizen initiatives plug into the work and help make it a reality. | Communication and interaction, Ownership, Intensity and levels of participation, Culture of participation, Mediation, Behavioural change, and Co-production. |

| Inclusive and multistakeholder governance as a result of a collaborative approach. | NBS require a collaborative approach that involves and engages all five stakeholders, developing governance that both influences and sets limits for all five, while ensuring that the strengths and weaknesses of each actor are integrated into the division of roles and responsibilities. | In Sofia (Bulgaria), the Bread Houses Network is supported by the other actors and stakeholders to co-deliver the benefits of participation to citizens in the district of Nadezhda. | Communication and interaction, Private sector, Co-production, Cultural mapping, and Governance. |

| Bridging differences through an inclusive and highly attractive narrative. | An inclusive and highly attractive narrative (vision and mission) for the implementation of NBS can help bridge differences between municipal departments, participating businesses, and organisations, and between the different housing blocks in neighbourhoods. | The vision for Helsingborg (Sweden) is that, by 2035, the city will be creative, pulsating, inclusive, and balanced for people and businesses. The city by then will be exciting, attractive, and sustainable. This common vision, which is defined in more detail locally, informs and governs all NBS and other regenerative activities in the city. | Inclusion, Trust, Governance, and Communication and interaction. |

| Effectiveness, achievements, scaling up, and replication as a result of monitoring and evaluation. | The design, monitoring, and evaluation of NBS need to be arranged so that the effectiveness and achievements can be measured and analysed, enabling successful NBS to be scaled up and repeated in other similarly deprived areas. | In the municipality of Høje-Taastrup (Denmark), the stakeholders are transferring documented models using URBiNAT co-creation methods from one deprived neighbourhood, Charlottekvarteret, where the quality of life has improved, to another neighbourhood in the city, where there is the potential to achieve similar results. | Monitoring and evaluation, Private sector, Behavioural change, and Co-production. |

References

- European Commission. Horizon 2020 Work Programme 2016–2017: 17. Cross-Cutting Activities (Focus Areas). 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2016_2017/main/h2020-wp1617-focus_en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Borgström, S.; Gorissen, L.; Egermann, M.; Ehnert, F. Nature-Based Solutions Accelerating Urban Sustainability Transitions in Cities: Lessons from Dresden, Genk and Stockholm Cities. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaz, E.; Anthony, A.; McHenry, M. The geography of environmental injustice. Habitat Int. 2017, 59, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Egusquiza, A.; Cortese, M.; Perfido, D. Mapping of innovative governance models to overcome barriers for nature based urban regeneration. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 012081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General for Research and Innovation (European Commission). Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda for Nature-Based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities: Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on ‘Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities’ (Full Version); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, J.; Jacobs, S. Nature-Based Solutions for Europe’s Sustainable Development. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wamsler, C.; Alkan-Olsson, J.; Björn, H.; Falck, H.; Hanson, H.; Oskarsson, T.; Simonsson, E.; Zelmerlow, F. Beyond participation: When citizen engagement leads to undesirable outcomes for nature-based solutions and climate change adaptation. Clim. Chang. 2020, 158, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Somarakis, G.; Stagakis, S.; Chrysoulakis, N. (Eds.) ThinkNature Nature-Based Solutions Handbook, Project Funded by the EU Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 730338; Foundation for Research and Technology—Hellas: Heraklion, Greece, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H. Nature-based Solutions: Towards sustainable communities—Analysis of EU-funded projects. In Nature-Based Solutions—State of the Art of EU-Funded Projects; Directorate-General for Research & Innovation (European, Commission); Wild, T., Freitas, T., Vandewoestijne, S., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 156–180. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, P.; Mustelin, J. Planning for Climate Change: Is Greater Public Participation the Key to Success? Urban Policy Res. 2013, 31, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Schweizer, P.-J. Inclusive risk governance: Concepts and application to environmental policy making. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, H.L.P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Runhaar, H.A.C. “Cool” governance of a “hot” climate issue: Public and private responsibilities for the protection of vulnerable citizens against extreme heat. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Hüesker, F.; Lupp, G.; Begg, C.; Huang, J.; Oen, A.; Vojinovic, Z.; Kuhlicke, C.; Pauleit, S. Stakeholder Mapping to Co-Create Nature-Based Solutions: Who Is on Board? Sustainability 2020, 12, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaas, E.; Neset, T.-S.; Kjellström, E.; Almås, A.-J. Increasing house owners adaptive capacity: Compliance between climate change risks and adaptation guidelines in Scandinavia. Urban Clim. 2015, 14, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.L.T.; Mees, H.L.P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Runhaar, H.A.C. The Roles of Residents in Climate Adaptation: A systematic review in the case of the Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, H.L.P.; Uittenbroek, C.J.; Hegger, D.L.T.; Driessen, P.P.J. From citizen participation to government participation: An exploration of the roles of local governments in community initiatives for climate change adaptation in the Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2019, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z. Theoretical Framework of Inclusive Urban Regeneration Combining Nature-Based Solutions with Society-Based Solutions. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G. Beyond the rhetoric of participation: New challenges and prospects for inclusive urban regeneration. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven lessons for planning nature-based solutions in cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpini, M.X.D.; Cook, F.L.; Jacobs, L.R. Public Deliberation, Discursive Participation, and Citizen Engagement: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2004, 7, 315–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action: Presidential Address, American Political Science Association, 1997. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1998, 92, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- URBiNAT. Deliverable D3.3—Portfolio of Purposes, Methods, Tools and Content: Forming Digital Enablers of NBS. Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; IKED: Malmö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M. A Measurement Framework for Assessing the Contribution of Social Media to Public Engagement: An empirical analysis on Facebook. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 1289–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonsón, E.; Perea, D.; Bednárová, M. Twitter as a tool for citizen engagement: An empirical study of the Andalusian municipalities. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Min, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Evans, R. Unpacking the black box: How to promote citizen engagement through government social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Comput. Human Behav. 2020, 110, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, K.E.; Rice, R.E. Digital Divides From Access to Activities: Comparing Mobile and Personal Computer Internet Users. J. Commun. 2013, 63, 721–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörschelmann, K.; Werner, A.; Bogacki, M.; Lazova, Y. Taking Action for Urban Nature: Citizen Engagement Handbook, NATURVATION Guide. Project Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 730243. 2019. Available online: https://naturvation.eu/result/taking-action-urban-nature-citizen-engagement (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Nature4Cities. Knowledge and Assessment Platform for Nature Based Solutions. Project Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No 730468. 2017. Available online: https://nature4cities-platform.eu/#/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- NetworkNature. Nature-based Solutions Task Forces. Project Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 887396. 2021. Available online: https://networknature.eu/networknature/nature-based-solutions-task-forces (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Santos, B.d.S. (Ed.) Cognitive Justice in a Global World: Prudent Knowledges for a Decent Life; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; p. 462. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.d.S. The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South; Duke University Press Books: Durham, NC, USA, 2018; p. 392. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. Deliverable D3.1—Strategic Design and Usage of Participatory Solutions and Relevant Digital Tools in Support of NBS Uptake. Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; Danish Technological Institute (DTI): Aarhus, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, I.; Caitana, B.; Nunes, N. Policy Brief: Municipal Committees Experimenting in Innovative Urban Governance and Nature-Based Projects, Aimed at Inclusive Urban Regeneration; ICLD—Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy: Visby, Sweden, in press.

- URBiNAT. Deliverable D3.2—Community-Driven Processes to Co-Design and Co-Implement NBS. Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. Deliverable D2.3—On the Establishment of URBiNAT’s Community of Practice (CoP). Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; IKED: Malmö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CES-UC. About CES—Overview. 2021. Available online: https://ces.uc.pt/en/ces/sobre-o-ces (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Madzak, M.V.; Hougaard, K.F.; Hilding-Hamann, K.E. Kortlægning af Interne og Eksterne Initiativer Med Fokus på Entreprenørskab Inden for Udsatte Boligområder; Danish Technological Institute (DTI): Aarhus, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. Deliverable D1.5—Compilation and Analysis of Human Rights and Gender Issues (Year 1). Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.d.S.; Avritzer, L. Introduction: Opening up the Canon of Democracy. In Democratizing Democracy: Beyond the Liberal Democratic Canon; Santos, B.d.S., Ed.; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. xxxiv–lxxiv. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. URBiNAT NBS Catalogue. 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/nbs-catalogue/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Moniz, G.C.; Ferreira, I. Healthy Corridors for Inclusive Urban Regeneration. In Rassegna di Architettura e Urbanistica—How Many Roads, 158; Quodlibet: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, I.A.R.G. Desenvolvimento Sustentável e Corredores Verdes. Barcelos Como Cidade Ecológica. Master’s Thesis, University of Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. Deliverable D4.1—New NBS. Co-Creation of URBiNAT NBS (Live) Catalogue and Toolkit for Healthy Corridor of the URBiNAT Project, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; IAAC: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Caitana, B.; Nunes, N. Social and solidarity economy and rights-based approach in URBiNAT. In Deliverable D1.8/1.9—Compilation and Analysis of Human Rights and Gender Issues (Years 2 & 3) of the Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; URBiNAT, Ed.; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2021; pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mance, E.A. Redes de Colaboração Solidária. In Dicionário Internacional da Outra Economia; Cattani, A.D., Laville, J.-L., Gaiger, L.I., Hespanha, P., Eds.; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2009; pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Manca, A.R. Social Cohesion. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6026–6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- URBiNAT. Chapter 1—Citizens engagement. In Deliverable D1.2—Handbook on the Theoretical and Methodological Foundations of the Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; URBiNAT, Ed.; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 13–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R.H.; Wutich, A.; Ryan, G.W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; p. 552. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R.; Ryan, G.W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; p. 451. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. URBiNAT Ethical Principles. 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/ethics/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- URBiNAT. [Human Rights & Gender] Co-Designing Strategies for Inclusion, Based on Gender and Intersectional Approaches. 3 May 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/co-designing-strategies-for-inclusion-based-on-gender-and-intersectional-approaches/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- URBiNAT. [Human Rights & Gender] Towards a Rights-Based Approach for an Inclusive Urban Regeneration with Nature-Based Solutions. 25 August 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/human-rights-gender-towards-a-rights-based-approach-for-an-inclusive-urban-regeneration-with-nature-based-solutions/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- URBiNAT. Deliverable D6.1—Communication and Dissemination Plan (V2). Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; ITEMS: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL). About—Open and Digital Living Lab Days. 2021. Available online: https://openlivinglabdays.com/about-us/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Santos, B.d.S. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Hilding-Hamann, K.E. Interesting participatory cases. Non-public blog on URBiNAT’s Internal Collaborative Platform. Work Package 3 on Citizen Engagement in Support of NBS (Available upon Request to the Corresponding Author). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. Bread Houses: Social and Solidarity Economy Nature-Based Solution. 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/nbs_catalogue/bread-houses/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Savova-Grigorova, N. About Us | Bread Houses Network. 2021. Available online: https://www.breadhousesnetwork.org/about-us/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- URBiNAT. Presentation and Results of the Workshop “Co-Creating Solutions with Local Citizens and Stakeholders within European Projects”. 8 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- URBiNAT. Deliverable of the Workshop “Co-Creating Solutions with Local Citizens and Stakeholders within European Projects”. 8 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.d.S.; Nunes, J.A.; Meneses, M.P. Introduction: Opening Up the Canon of Knowledge and Recognition of Difference. In Another Knowledge Is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies; Santos, B.d.S., Ed.; Reinventing Social Emancipation toward New Manifestos; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. xix–lxii. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, T.; Freitas, T.; Vandewoestijne, S. (Eds.) Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission). Nature-Based Solutions—State of the Art in EU-Funded Projects; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, J.J.T.; Trebic, T.; Anguelovski, I.; Wood, E.; Thery, E. (Eds.) Green Trajectories: Municipal Policy Trends and Strategies for Greening in Europe, Canada and United States (1990–2016); BCNUEJ: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Turnhout, E.; Metze, T.; Wyborn, C.; Klenk, N.; Louder, E. The politics of co-production: Participation, power, and transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, T. Research & innovation priorities in Horizon Europe and beyond. In Nature-Based Solutions—State of the Art of EU-Funded Projects; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission); Wild, T., Freitas, T., Vandewoestijne, S., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H. Governing NBS: Towards transformative action. In Nature-Based Solutions—State of the Art of EU-Funded Projects; Directorate-General for Research & Innovation (European Commission); Wild, T., Freitas, T., Vandewoestijne, S., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Nature4Cities. Deliverable D5.2—Citizen and Stakeholder Engagement Strategies and Tools for NBS Implementation. Project Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No 730468. 2018. Available online: https://www.nature4cities.eu/results (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Kaiser, M.L.; Hand, M.D.; Pence, E.K. Individual and Community Engagement in Response to Environmental Challenges Experienced in Four Low-Income Urban Neighborhoods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fung, A. Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban Democracy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004; p. 278. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.d.S. A Critique of Lazy Reason: Against the Waste of Experience and Toward the Sociology of Absences and the Sociology of Emergences. In Epistemologies of the South; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 164–187. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.d.S.; Mendes, J.M. (Eds.) Demodiversity: Towards Post-Abyssal Democracies, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Honey-Rosés, J.; Anguelovski, I.; Chireh, V.K.; Daher, C.; Bosch, C.K.v.d.; Litt, J.S.; Mawani, V.; McCall, M.K.; Orellana, A.; Oscilowicz, E.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions—design, perceptions and inequities. Cities Health 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- URBiNAT. In times of pandemic: Mapping backlashes, social challenges and solidarity responses with URBiNAT cities. In Deliverable D1.8/1.9—Compilation and Analysis of Human Rights and Gender Issues (Years 2 & 3) of the Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; URBiNAT, Ed.; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2021; pp. 34–77. [Google Scholar]

- Megglé, C. Coronavirus, Confinement et Quartiers Populaires: Des Vulnérabilités Particulières à Prendre en Compte. Localtis, un Média Banque des Territoires. 25 March 2020. Available online: https://www.banquedesterritoires.fr/coronavirus-confinement-et-quartiers-populaires-des-vulnerabilites-particulieres-prendre-en-compte (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Berkowitz, R.L.; Gao, X.; Michaels, E.K.; Mujahid, M.S. Structurally vulnerable neighbourhood environments and racial/ethnic COVID-19 inequities. Cities Health 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R. [COVID-19] Challenges, Responses and Solidarity in Brussels. URBiNAT—News. 4 June 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/covid-19-challenges-responses-and-solidarity-in-brussels/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Campos, R. [COVID-19] Challenges, Responses and Solidarity in Nantes. URBiNAT—News. 18 May 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/covid-19-challenges-responses-and-solidarity-in-nantes/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Campos, R. [COVID-19] Challenges, Responses and Solidarity in Porto. URBiNAT—News. 11 May 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/covid-19-reflections-on-the-impact-of-the-pandemic-part-i-porto/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Anguelovski, I. COVID-19 Highlights Three Pathways to Achieve Urban Health and Environmental Justice. International Institute for Environment and Development—Urban. 27 August 2020. Available online: https://www.iied.org/covid-19-highlights-three-pathways-achieve-urban-health-environmental-justice (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Campos, R. [COVID-19] Challenges, Responses and Solidarity in Sofia. URBiNAT—News. 19 May 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/covid-19-challenges-responses-and-solidarity-in-sofia/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Campos, R. [COVID-19] Challenges, Responses and Solidarity in Høje-Taastrup. URBiNAT—News. 4 June 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/covid-19-challenges-responses-and-solidarity-in-hoje-taastrup/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Campos, R. [COVID-19] Challenges, Responses and Solidarity in Nova Gorica. URBiNAT—News. 4 June 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/covid-19-challenges-responses-and-solidarity-in-nova-gorica/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Campos, R. [COVID-19] Challenges, Responses and Solidarity in Siena. URBiNAT—News. 9 June 2021. Available online: https://urbinat.eu/articles/covid-19-challenges-responses-and-solidarity-in-siena/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Gelli, F. Partecipazione e Fragilità. Osservatorio su Città e Trasformazioni Urbane. Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. 19 October 2020. Available online: https://fondazionefeltrinelli.it/partecipazione-e-fragilita/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Allegretti, G. Ricostruire la Partecipazione Civica Nella Nuova Normalità. Alcuni Indirizzi Per Una Possibile Rifondazione. Contesti Città Territ. Progett. 2020, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorronsoro, B. Gender mainstreaming. In Deliverable D1.2—Handbook on the Theoretical and Methodological Foundations of the Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; URBiNAT, Ed.; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lettoun, S. Human rights-based approach in urban regeneration. In Deliverable D1.2—Handbook on the Theoretical and Methodological Foundations of the Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; URBiNAT, Ed.; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lettoun, S. Applying SDGs framework. In Deliverable D1.2—Handbook on the Theoretical and Methodological Foundations of the Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; URBiNAT, Ed.; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferreira, I.; Duxbury, N. Cultural projects, public participation, and small city sustainability. In Culture in Sustainability: Towards a Transdisciplinary Approach; Asikainen, S., Brites, C., Plebańczyk, K., Rogač Mijatović, L., Soini, K., Eds.; SoPhi, University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2017; pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, A. The Contribution of Nature-Based Solutions to Socially Inclusive Urban Development—Some Reflections from a Social-environmental Perspective. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spada, P.; Allegretti, G. When Democratic Innovations Integrate Multiple and Diverse Channels of Social Dialogue: Opportunities and Challenges. In Using New Media for Citizen Engagement and Participation; Adria, M., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Allegretti, G. Participatory democracies: A slow march toward new paradigms from Brazil to Europe? In Cities into the Future; Lieberherr-Gardiol, F., Solinís, G., Eds.; Les Classiques des Sciences Sociales: Chicoutimi, QC, Canada, 2014; pp. 141–177. [Google Scholar]

- Allegretti, G.; Antunes, S. The Lisbon Participatory Budget: Results and perspectives on an experience in slow but continuous transformation. Field Actions Sci. Rep. J. Field Actions 2014. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/3363 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- D’Hont, F. Visioning as Participatory Planning Tool: Learning from Kosovo Practices; UN-Habitat, SIDA: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Wilding, H.; Gould, R.; Taylor, J.; Sabouraud, A.; Saraux-Salaün, P.; Papathanasopoulou, D.; de Blasio, A.; Nagy, Z.; Simos, J. Healthy Cities in Europe: Structured, Unique, and Thoughtful. In Healthy Cities: The Theory, Policy, and Practice of Value-Based Urban Planning; de Leeuw, E., Simos, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 241–292. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Copenhagen Consensus of Mayors. Healthier and Happier Cities for All. 13 February 2018. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/publications/2018/copenhagen-consensus-of-mayors.-healthier-and-happier-cities-for-all-2018 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- De Leeuw, E. One Health(y) Cities. Cities Health 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igoe, M. Can ‘Nature-Based Solutions’ be More than a Buzzword? Devex News. 13 December 2019. Available online: https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/can-nature-based-solutions-be-more-than-a-buzzword-96216 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Nelson, D.R.; Bledsoe, B.P.; Ferreira, S.; Nibbelink, N.P. Challenges to realizing the potential of nature-based solutions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 45, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Pub: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- André, I.; Abreu, A. Dimensões e espaços da inovação social. Finisterra 2006, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation: Ways to Design, Develop and Grow Social Innovation; Young Foundation and NESTA: London, UK, 2010; p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, N.; Caitana, B. The appropriation of citizenship rights in the promotion of social cohesion and urban social innovation. In Deliverable D1.2—Handbook on the Theoretical and Methodological Foundations of the Project URBiNAT, Funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No 776783; URBiNAT, Ed.; Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES-UC): Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

| Categories of Guideline 1 | Prioritization 2 | Overview of the Categories | Impact of Other Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication and interaction | 1 | Communicating specificities for interacting with citizens. | Trust |

| Behavioural changes | 2 | Instigating behavioural adjustments, or changes in behaviour, in some particular respect. | Communication and interaction |

| Trust | 3 | Improving or creating relationships of trust between citizens, and between citizens and city staff, politicians, and other agents. | Transparency, Inclusion, Communication and interaction, Governance |

| Co-production | 4 | Stimulating and improving the co-production of public services, participatory processes, and product development. | Trust and Behavioural change |

| Inclusion | 5 | Having specific guidelines to guarantee the inclusion of diversity. | Citizenship rights, Governance, Transparency, Regulation |

| Regulation | 5 | Clarifying rules and regulations for equal rights in the expression of visions and priorities. | Governance, Transparency, Trust |

| Governance | 6 | Balancing interactions among citizens, city staff, politicians, and other agents. | Trust, Transparency, Culture of participation |

| Innovation cycle | 7 | Adopting processes of rupture and searching for alternative solutions in order to address concrete social problems. | Citizenship rights |

| Transparency | 8 | Arguments for encouraging efforts to act in a transparent manner. | Trust, Governance, Why participation, Monitoring and evaluation |

| Intensity and levels of participation | 8 | Setting different approaches and levels of participation depending on the goals and real conditions for participation. | Culture of participation |

| Citizenship rights | 9 | Broadening the meaning of the appropriation of social, urban, political, and cultural rights, both internally in the collective imagination, and externally in rejuvenated relationships with local powers. | Inclusion |

| Cultural mapping | 10 | Articulating and making visible the multilayered cultural assets, aspects, and meanings of a place. | Inclusion, Innovation cycle, Supportive methodologies and techniques |

| Facilitation | - | Having specific guidelines to address facilitation that include other participatory guidelines. | Supportive methodologies and techniques |

| Quality of deliberation | - | Setting a meaningful deliberation process. | Regulation, Governance, Citizenship rights, Facilitation |

| Where | - | Having guidelines for the spaces in which the participatory events are held. | Communication and interaction, Facilitation |

| When | - | Identifying the best moment for the participatory events. | Communication and interaction, Facilitation |

| Supportive methodologies and techniques | - | Using specific methodologies and guidelines to support mobilization and inclusivity. | Communication and interaction, Facilitation, Cultural mapping |

| Integration of the results of participatory processes | - | Enlarging the scope of co-creation to validate the ideas developed. | Communication and interaction, Facilitation, Supportive methodologies and techniques |

| Private sector | - | Mapping the relevant private sector actors with interests in, and input to, the NBS targeted area. | Co-production, Innovation cycle |

| Monitoring and evaluation | - | Addressing the monitoring and evaluation of the participatory processes. | Transparency, Ownership |

| Risk assessment and mitigation measures | - | Identifying the factors influencing the co-creation processes, as well as those leading to the failure of co-creation and co-production. | Monitoring and evaluation, Transparency |

| Ownership | - | Citizens having ownership of both problems and solutions. | Trust, Communication and interaction |

| Culture of participation | - | Enabling regular interaction with citizens, and increasing the culture of participation. | Governance, Intensity and levels of participation |

| Why | - | Being clear as to why we need to engage citizens and support participatory processes. | Transparency, Intensity and levels of participation |

| Mediation | - | Dialogue and collaboration. | Communication and interaction, Trust, Facilitation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nunes, N.; Björner, E.; Hilding-Hamann, K.E. Guidelines for Citizen Engagement and the Co-Creation of Nature-Based Solutions: Living Knowledge in the URBiNAT Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313378

Nunes N, Björner E, Hilding-Hamann KE. Guidelines for Citizen Engagement and the Co-Creation of Nature-Based Solutions: Living Knowledge in the URBiNAT Project. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313378

Chicago/Turabian StyleNunes, Nathalie, Emma Björner, and Knud Erik Hilding-Hamann. 2021. "Guidelines for Citizen Engagement and the Co-Creation of Nature-Based Solutions: Living Knowledge in the URBiNAT Project" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313378

APA StyleNunes, N., Björner, E., & Hilding-Hamann, K. E. (2021). Guidelines for Citizen Engagement and the Co-Creation of Nature-Based Solutions: Living Knowledge in the URBiNAT Project. Sustainability, 13(23), 13378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313378