1. Introduction

UK town centers and high streets are recognized as sleeping giants for many. This syndrome has an international resonance and dates back to the 1970s and 1980s when the rise of a ‘retail revolution’ undermined the vitality and viability of several town centers as traditional shopping destinations [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In addition to retail capital concentration/internationalization and store concepts and formats diversification, which created an increasingly competitive and convenient shopping environment, the different waves of such retail revolution also significantly transformed the spatial organization of urban shopping systems [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Residential and retail decentralization has been consistently identified as one of the main drivers of the decline in the attractiveness of traditional shopping districts. Moreover, in the new millennium, digital technologies, such as the internet and hi-tech mobile devices, have encouraged the growth of online and mobile retailing [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Unsurprisingly, we have witnessed a switch from multichannel business models, mostly operated by independent retailers, to omnichannel business models, in which retail companies actively explore the assets of both physical and virtual worlds [

12,

13,

14]. Such a shift has affected companies’ store portfolio management strategies as some retailers have been assessing the need to relocate or even close part of their premises. Therefore, several town centers and high streets have been experiencing a withdrawal from numerous retailers [

15,

16]. These retail switches, which were recently accelerated by the uncertainty of the COVID-19 lockdown regulations, have resulted in a downward spiral of traditional shopping districts, leading to reduced footfall and sales and an increase in the number of vacant stores [

15,

17,

18,

19].

The complexity of these fast retail changes poses new challenges for both policymakers and local stakeholders to respond to town center revitalization effectively. While retail-led regeneration projects were perceived as major engines of town center development in the 1990s, evidence suggests that such large-scale projects overlooked consultations with local communities and failed to address the local problems of several town centers and high streets [

20,

21,

22]. Therefore, recent policy interventions have advocated the introduction of new forms of local governance assuming that the existence of thriving and vibrant commercial districts depends on the development of place-based and collaborative management models amongst different local stakeholders [

8,

23,

24]. Business Improvement Districts (BIDs)—a public-private partnership in which property owners and/or business occupiers in a defined geographical area vote to pay an assessment that is ring-fenced for financing a wide range of additional place management services, such as cleaning, security and marketing—have been internationally heralded as one successful cooperative formula of local governance where local retailers work together to revitalize the business atmosphere and customer experience of their shopping districts [

25,

26,

27,

28]. This endeavor is mostly achieved by the place management services BIDs provide, which are considered the most visible aspect of their daily operations.

Drawing on the role of BIDs as place management services providers, this paper aims to examine which strategic and operational placemaking priorities have been incorporated in BIDs’ business plans—a place-based strategic document voted on by BID members which, among other features, lists the range of activities that the BID will provide in each term—and how such place management activities have longitudinally evolved. Based on the former, and actually existing, government-funded pilot BIDs in the UK and through an exploratory research design that combines a qualitative and quantitative thematic analysis of 72 BIDs’ business plans, this paper opens up key questions for discussing whether and how UK BIDs have been developing adaptative strategies to respond to the challenges that have been undermining the long-term sustainability of traditional shopping districts. With this demarche, this paper also aims to contribute to the recent research agenda set by Grail et al. [

29] and Cotterill et al. [

30], who claim that knowledge about the longitudinal evolution of the operational activities carried out by UK BIDs is limited.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces BIDs as a form of local governance and discusses their revitalization aspirations as place management services providers. It moves on to outline our methodological approach.

Section 4 provides a comprehensive thematic analysis of the operational activities included in BIDs’ business plans and longitudinally examines how these activities have evolved. The paper ends with a discussion of the main findings, advances with a new framework on how place management associations operate and debates how BIDs should embrace both physical and online channels to ensure the viability and vitality of town centers and high streets in the digital age.

2. Business Improvement Districts (BIDs): Background, Definition and Aspirations

BIDs flourished as a response to the economic and demographic decline of urban shopping districts in North America because of the harmful effects that the opening of several out-of-town shopping centers in the 1950s and 1960s had on the vitality of traditional shopping precincts. Moreover, BIDs also arose as a product of the progressive fiscal constraints faced by local and central governments, which undermined the efficiency and effectiveness of management models in traditional shopping districts [

28,

31,

32]. Concerned about ‘business climate’ deterioration in a small shopping district west of the city of Toronto, some members of the existing local businesspeople association—Bloor-Jane-Runnymede Businesspeople Association—sought to develop a set of promotional activities to address town center pressures in the late 1960s. However, some local merchants concluded that the existing voluntary contributions were incompatible with the long-term sustainability of these revitalization initiatives due to the prevalence of numerous free riders (i.e., members who do not contribute to the revitalization efforts although they may benefit from them) [

33,

34]. Thus, some local businesses, in partnership with local government, pursued to restructure the governance geometry between public and private stakeholders in the management of urban shopping districts and advocated for the creation of an independent organization capable of imposing a levy on all commercial owners to ensure long-term support for additional revitalization activities through mandatory revenue-raising rules [

35,

36]. In December 1969, the province of Ontario passed the enabling legislation, and, six months later, Bloor-Jane-Runnymede became the first BID in the world [

31,

32,

33].

During the 1970s, along with their spread across Canada, BIDs were first territorialized in the US, New Orleans, in 1974 to respond to the same vulnerabilities that also plagued the economic viability and vitality of traditional shopping districts in several Canadian town centers, namely out-of-town competition and local government fiscal shrinkages [

26,

35,

36,

37,

38]. The rapid spread of BIDs in the US in the 1990s and 2000s—from around 400 in 2000 to over 1000 in 2010 and over 2000 nowadays—discloses that thousands of US town centers found that BIDs, as opposed to traditional municipal management, are an innovative and effective emergency tool for the revitalization of several urban shopping districts [

26,

28,

31,

32,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

While BIDs are originally a ‘made-in-Toronto’ invention, it has been the success stories of US BIDs—placed in New York, Philadelphia, and Washington—that have been presented as BIDs’ ‘mecca places’ on international policy tourism circuits [

31,

41,

42,

43]. Consequently, in the late 1990s, BIDs spread to Australia, New Zealand and South Africa [

31,

32]. The BID ‘model’ reached Europe in the early 2000s when England and Wales passed their first regulations in 2004 and 2005, respectively [

31,

41,

42]. Scotland, Germany, the Republic of Ireland, Serbia and Albania followed [

44,

45,

46]. More recently, BIDs have also been territorialized in Northern Ireland, the Netherlands and Japan since 2010. Many other countries are currently developing pilot experiences or discussing enabling legislation, namely Spain (where the autonomous community of Catalonia was the first to pass the enabling legislation in December 2020), Brazil, Sweden, Denmark, Gibraltar, Singapore and the Bahamas [

47].

As BIDs have been territorialized in different institutional arrangements over the last 50 years, conceptualizing a single BID definition is a laborious duty. This suggests that BIDs are a porous and flexible urban policy that easily adapts to different territorial contexts. However, BIDs share a set of common characteristics [

26,

35,

41,

48]. First, they are a form of hyperlocal governance, geographically bounded and managed through a public-private partnership, usually for up to 5 years, which may be extended. Second, although BID implementation is only possible through enabling public legislation, BIDs are invariably proposed, endorsed and managed by local private stakeholders (‘proponent group’), such as property owners and/or business occupiers. Third, BIDs are democratic organizations as their formation and renewal become legally binding based on majority approval of the business plan—a strategic document in which the proponent group, after local consultations with the members of the area, reaches an agreement on the boundaries of the BID, its governance and financing models and the range of activities that the BID will provide. Fourth, if the business plan is approved in a ballot, BIDs then become self-funded organizations whose revenues are obtained through a mandatory levy that is imposed on all property owners and/or business occupiers within the BID area. In some BIDs, local and central governments also contribute with additional funding grants. Fifth, these proceeds are ring-fenced in the BID area to finance a range of services in addition to those traditionally provided by city governments and which were previously defined and subsequently voted on by BID members. However, the relationship between BIDs and local authorities has been dynamic over time as local authorities’ fiscal shrinkage following the 2008 recession impacted BIDs’ operations. Therefore, BIDs were then forced to take on public realm services that local authorities struggled to provide, thus raising criticisms in the face of progressive private governance of urban spaces [

49,

50,

51]. Based on these features, we may define a BID as a geographically bounded area, authorized by local governments through enabling legislation, in which property owners and/or business occupiers democratically decide to make a collective contribution through an additional mandatory levy to finance complementary public services and marketing programs aimed at revitalizing their shopping district.

While most BIDs worldwide share these general characteristics, there are variations in their operating mechanisms as BIDs respond differently to each neighborhood’s problems [

40,

51,

52]. Therefore, BIDs are hyperlocal forms of governance that enable community-based decision-makers, such as property owners and/or business occupiers, to negotiate and determine which activities should be prioritized in their area [

26,

37]. In broad terms, BIDs aspire to increase the overall place coolness and the business climate through the provision of placemaking activities aimed at improving and manipulating the appearance, security perception, maintenance, convenience and experience of town centers for businesses, residents and visitors, thus emulating for traditional shopping districts the successful management model of out-of-town shopping centers [

26,

28,

52,

53]. It is, hence, undeniable that the services and activities that BIDs provide are the most visible facet of their daily operations as a place management organization.

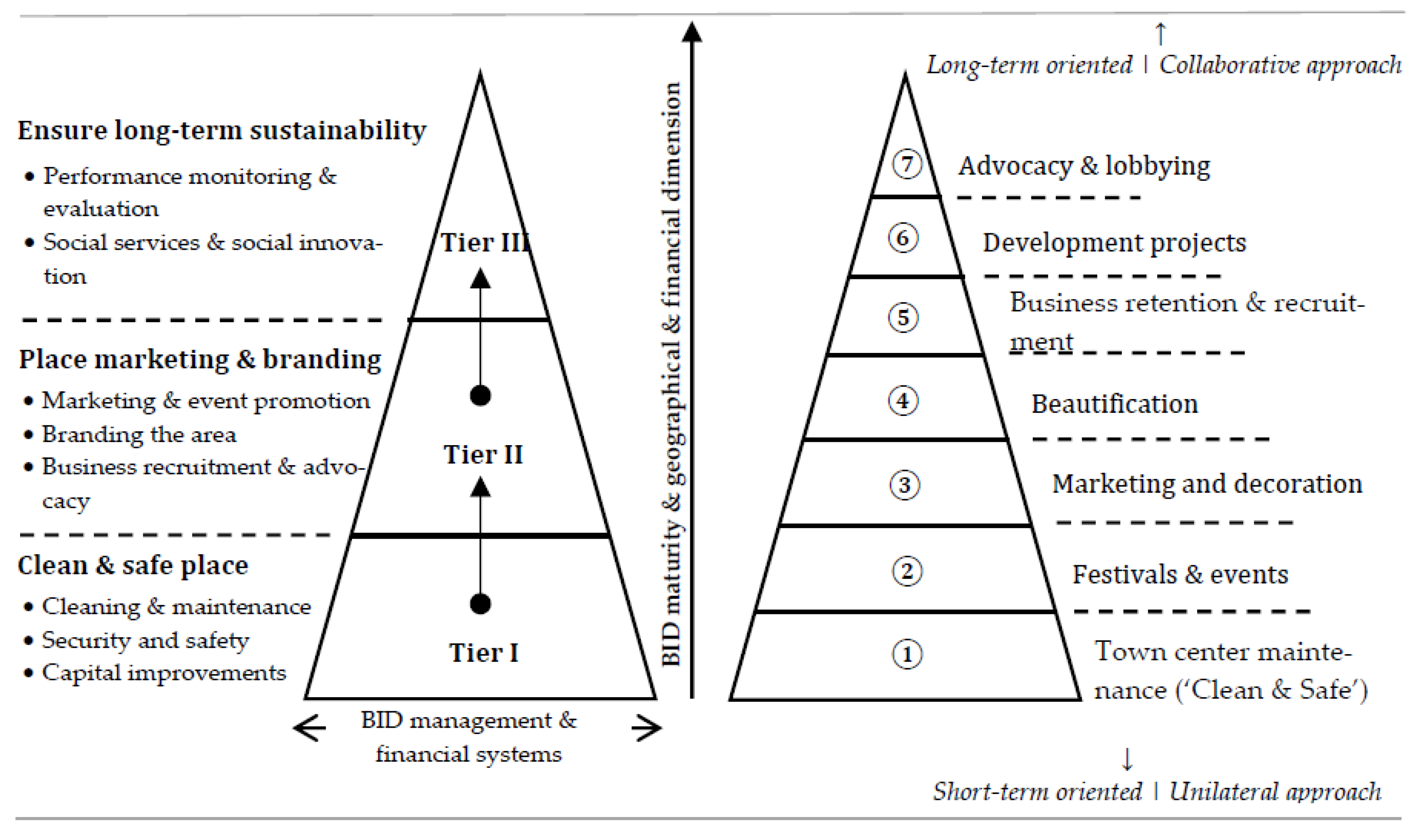

According to Ward and Cook [

41], BIDs tend to focus on three clusters of services and activities: first, and following the traditional ‘clean, green and safe’ mantra, cleansing and maintenance services, in terms of streetscape appearance and its beautification, are often an initial priority; second, security and safety, in terms of creating a feeling of personal and business security through patrolling teams and surveillance technologies; third, marketing and branding place’s attributes and decorating the BID area aim to create or increase reasons for visiting the area. However, contrary to what has been advocated by some studies, limiting the role of BIDs largely to the basics of the place management spectrum—‘clean, green and safe’ and destring branding and marketing—is not to capture the whole picture of their role as services providers and their strategic and transformative influence on a range of urban governance issues [

27,

37,

40].

The strategic influence that BIDs can play is strongly related to the local needs of the area where the BID operates. When Hoyt [

54], in collaboration with the International Downtown Association, conducted the first international systematic examination on the types of services BID-like organizations provided in different territories, she concluded that most BIDs in South Africa were very involved in security and maintenance services while in Canada most of them prioritized capital improvements and consumer marketing services. Moreover, according to some studies [

39,

53,

55,

56,

57], the strategic influence that BIDs can achieve locally also depends on their geographical and financial dimensions as these attributes influence the range of services BIDs deliver. As noted, private stakeholders are the main funding base for many BIDs. For this reason, the greater the number of businesses’ premises and their ratable value, the greater the financial dimension of the BID and, hence, the median number of services delivered [

36,

55]. For instance, in New York City, Gross [

55] found that larger size BIDs had substantial annual operating budgets, thus offering more higher-tier services when compared to smaller BIDs in spatial and financial terms, which often provide a lower range of activities.

Mitchell [

39,

53], Gopal-Agge & Hoyt [

56] and Yanchula [

58] analyzed the evolving nature of different place management organizations (e.g., BIDs) as services providers in North America and systematized through a longitudinal analysis the bands of services that these organizations have generally been delivering in their areas. A common conclusion that can be drawn from these studies is that BIDs’ services go far beyond the traditional focus on the political economy of the place and particularly on the role that public space design plays in the way an area is experienced and how people behave and interact [

59,

60,

61]. As

Figure 1 suggests, place management organizations, including BIDs, tend to disclose an ascending hierarchical structure within the scope of the place management spectrum as their maturity and geographic and financial dimensions expand [

56,

58]. Consequently, it has been found that these place management organizations often begin their operations with services aimed at improving the maintenance and security of the area in order to make consumption districts amenable in response to consumers’ basic expectations [

53]. For example, several studies have shown that BIDs pursue an early ‘clean and safe’ passage through the implementation of what Sanscartier and Gacek [

62] termed ‘socioeconomic hygiene practices’, such as public video surveillance systems, ambassadors’ patrols and capital investments in the public space, aimed at creating a ‘sense of place’ and producing a consumer-friendly atmosphere [

61,

63,

64,

65]. However, over time, BIDs’ activities and services, including the teams of ambassadors, go far beyond the traditional ‘janitorial and safety role’ as they become increasingly engaged with marketing and urban branding services, including ‘making and telling the story of the area’ through branding and experiential marketing strategies, such as thematic events and nightlife vibrancy [

39,

53,

64,

65,

66,

67]. Yet Yanchula [

58] (p. 94) noted that marketing services, which comprises the interactive teams of ambassadors, are limited to produce knowledge about “who are the consumers that have been attracted to the place, what their spending habits are [and] what their wants and needs are” as a means to create strategies to promote the area and create loyalty programs for these visitors in the future [

64,

65]. Lastly, while some studies have suggested that BIDs play a relatively modest role in urban politics [

37,

49,

53], others have argued that as BIDs approach the top of the pyramid of place management services—along with the widening of their geographical and financial dimension—they become increasingly engaged with built environment rehabilitation and street repurposing [

37,

68,

69]. At this stage of the place management pyramid, on the one hand, BIDs tend to advocate the interests of their members and lobby the city government to implement structural intervention projects in public spaces. Unsurprisingly, numerous recent studies have suggested that BIDs—and above all their directors—have become powerful actors in urban governance networks over the last decades [

70,

71]. For instance, Morçöl et al. [

70] found that the director of a BID in Philadelphia advocated for policy positions that comprised, in addition to street cleaning, citywide issues affecting the BID area, such as land-use planning or local income tax. Similarly, BIDs at this stage also often engage with social integration programs and community-based initiatives targeted at addressing the needs of vulnerable groups, such as panhandlers and the homeless [

53,

57].

An outstanding aspect that resonates from this discussion is that the literature on the longitudinal analysis of BIDs as placemaking services providers is strongly North American-centered (see [

50,

72] for some UK case-based approaches). Therefore, the Institute of Place Management and the BID Foundation—UK-wide and professional institutions that provide cutting-edge knowledge on the BID industry—have very recently stressed that a detailed and systematic longitudinal analysis of the strategic priorities and operational activities in BIDs’ business plans and their relevance for the reinvention of the governance paradigms of town centers and high streets were still missing in the UK context [

29,

30]. This paper is an attempt to shorten this gap.

3. Materials and Methods

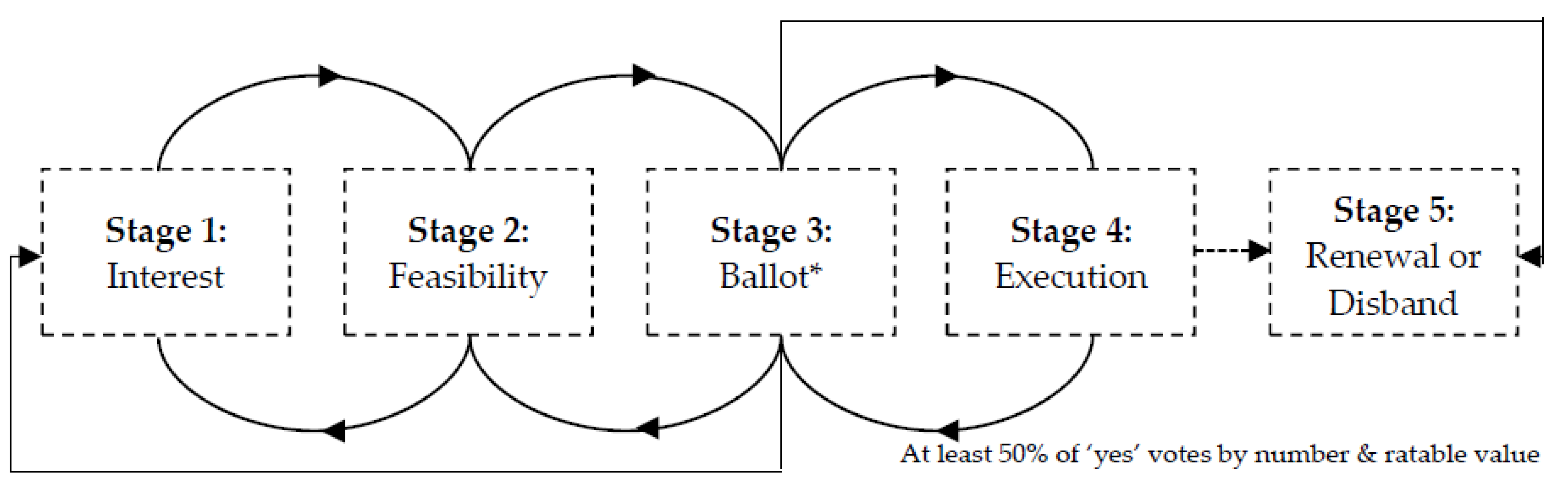

This paper aims to assess whether UK BIDs have been reinventing their place management paradigms and how their strategic priorities and operational activities have evolved over the years. Therefore, this study implemented an exploratory sequential research design based on the qualitative and quantitative longitudinal thematic analysis of the activities contained in some BIDs’ business plans in the UK as the main technique of inquiry. As discussed earlier, business plans are strategic planning documents in which the BID proponent group, after conducting local consultations with potential BID members, reaches an agreement on the boundaries of the BID and its governance structure, the predicted budget and levy rules and the range of placemaking services that the BID will deliver during its mandate. It should be noted that, after interest and feasibility stages, the resulting business plan is subject to a ballot. If the ballot is successful, the business plan is approved and, thus, locally implemented (

Figure 2).

While there are variations in BIDs’ regulations in each devolved nation—such as the need for a minimum 25% ballot turnout in Scotland and Northern Ireland and the possibility for both property owners and occupiers to finance the BIDs in Scotland (in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, only business occupiers are levy-payers, although some exceptions exist)—forming a BID is strictly dependent on the approval of the business plan in a ballot [

73,

74,

75,

76].

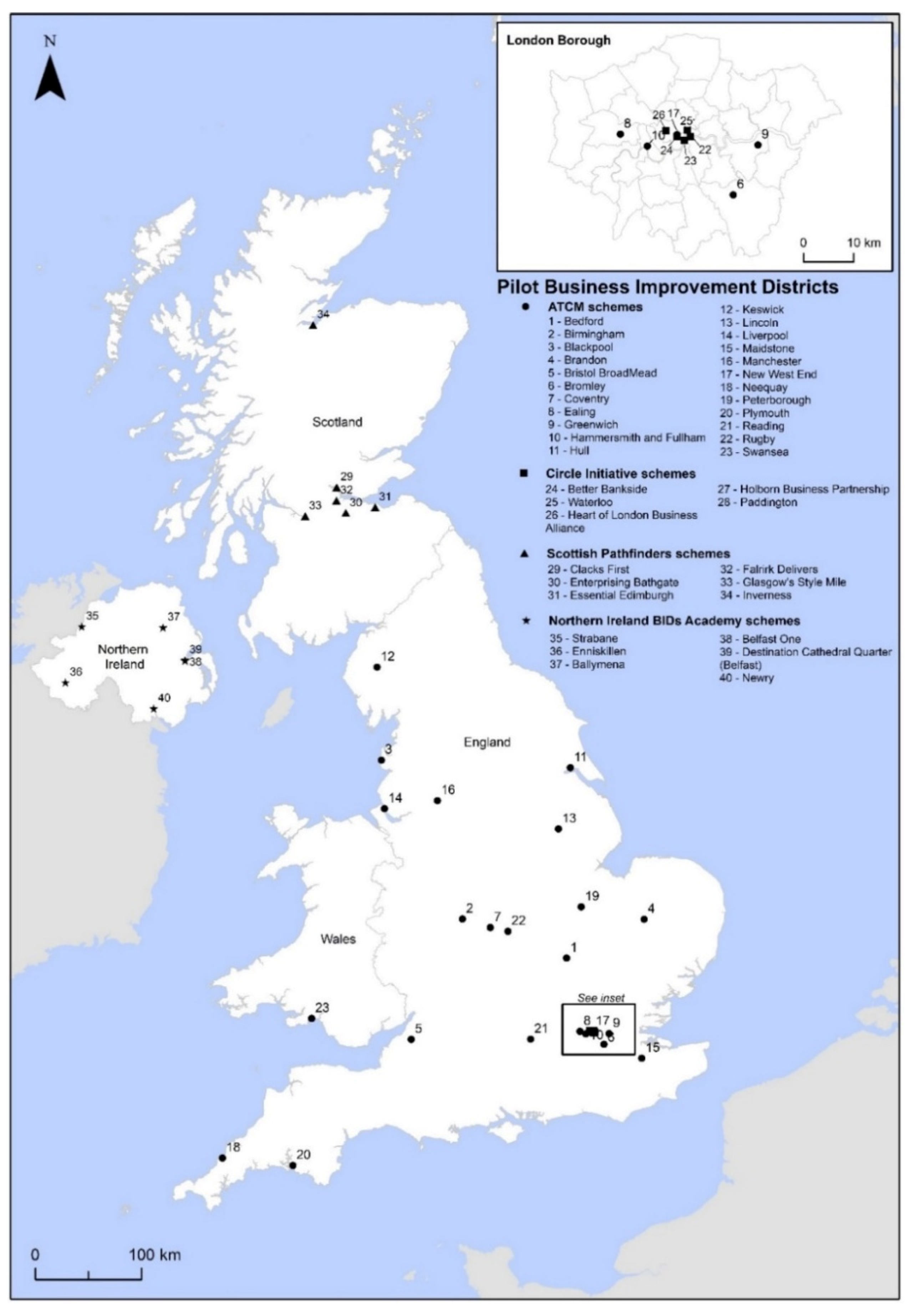

For these reasons, our study sample consisted of 31 BIDs that, in addition to remaining in operation at the time of writing, were also part of the government-funded pilot programs in the UK (

Figure 3). To that end, our methodological approach encompassed three main stages. First, 40 UK BIDs schemes, established under the different government-funded pilot programs, were identified [

77,

78,

79]. In England and Wales, 28 pilot BIDs were created under two pilot programs: ‘The Circle Initiative’ program, which established five pilot BIDs in central London between 2001 and 2005, and the National BID Pilot Project (23 BIDs), coordinated by the Association of Town and City Management (ATCM) between January 2003 and June 2005 [

42,

80]. In 2005, the Scottish Executive created a steering group to establish six pilots aimed at showing the practical application of BIDs while contributing to legislation development. However, rather than following the English and Welsh ‘business-led model’, Scotland has opted for a ‘community-led model’ to be introduced in broader and more vulnerable spatial contexts beyond town centers and retailing, including rural and industrial areas. Consequently, Scottish BIDs are referred to as Improvement Districts, thus emphasizing community empowerment initiatives in Scotland’s towns revitalization as opposed to the ‘business model’ found in England and Wales [

78,

81,

82]. In Northern Ireland, the government also supported the creation of six pilot BIDs in 2014 [

79].

Second, some of the former pilot BIDs were not found in operations at the time of writing and were therefore excluded from our analysis. First, we found no evidence to suggest that the Brandon BID and Greenwich BID currently lie in operations. On the one hand, these BIDs were not recorded as ‘established BIDs’ in the reports of the then National BIDs Advisory Service from ATCM [

77]. On the other hand, these same BIDs are not currently listed in the BID Index, which is developed and updated by the British BIDs—a UK-based organization that has unrivaled, first-hand knowledge and experience in the BID industry. The BID Index features BIDs in different development stages (under creation, established and failed). Second, the BID Foundation and Institute of Place Management have been conducting intensive research that found that some pilot BIDs failed their renewal ballots after the end of the pilot schemes and, thus, have not yet been established. For example, Keswick BID was the first UK BID to fail at its second term ballot and currently does not exist [

30], and Glasgow’s Style Mile BID failed after the pilot initiative [

78].

Third, the BID sample size included in our analysis (31) also depended on the availability of each BID’s business plans. This data was gathered on BIDs’ websites and in the absence of such information BIDs’ directors and managers were contacted by email in November 2020. In December 2020, BIDs that had not yet submitted their business plans received a final reminder to do so. As a result, we retrieved and included in our analysis 14 BIDs’ business plans in the first term, 18 in the second, 22 in the third term and 18 in the fourth term.

The research method applied to data collection was thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a highly flexible research technique that allows identifying, analyzing, describing and summarizing homogeneous thematic units within a rich, detailed and large data set in a well-structured way [

83,

84,

85]. However, as noted earlier, this study draws on an exploratory sequential research design that integrates both qualitative and quantitative results [

86]. Firstly, the qualitative phase was based on the thematic analysis of the business plans, which was conducted through a hybrid coding approach [

83,

87]. On the one hand, the coders (the authors of this paper) produced a previous deductive codebook as a data management tool that included detailed definitions of each code before conducting an in-depth thematic analysis of the businesses plans [

83,

84,

87]. In this sense, a deductive coding approach allows identifying relevant themes based on prior research. In our analysis, deductive categories were drawn from previous studies that focused on BIDs’ involvement in placemaking activities [

39,

53,

56,

58]. On the other hand, inductive coding approaches encompass themes that emerged directly from the data [

83,

84,

85]. In our analysis, most secondary codes encompassing specific BIDs’ activities emerged directly from the data after refining thematic units. At the same time, the in-depth thematic analysis of the business plans allowed to generate a new first-level code (digital presence and marketing)—hitherto not mentioned in the BID literature—through an inductive coding approach as none of the deductive categories accurately reflected the meanings of this new thematic category.

The MaxQDA2020 software program was used to sort, organize and analyze BIDs’ business plans to conduct in-depth longitudinal thematic analysis. The coding process was performed by two coders, thus increasing the study’s credibility [

85]. After conducting the coding process individually and independently, the two coders adopted data validation and curation techniques, such as peer debrief meetings, to discuss the coding process and keep track of emerging and final categories and coded segments [

85,

87].

Secondly, after the qualitative thematic analysis of the business plans, the thematic units previously defined (deductive codes) or the ones that emerged from the data (inductive codes) were quantified using MaxQDA. As a result, coded segments were transformed into variables (i.e., quantitative thematic analysis). Subsequently, it was possible to compare the changes in the strategic priorities and operational activities of the former UK pilot BIDs over different follow-up times through three methodological steps. First, the non-existence of significant differences between the variances of the various groups was confirmed through Levene’s test. Second, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) between groups (i.e., BIDs’ terms) was conducted. ANOVA is a quantitative technique used to determine whether the means of distinct samples are significantly different. This technique allowed us to identify longitudinal shifts in the BIDs’ operational activities considering each BID term [

88,

89]. Third, a posthoc test (Gabriel’s test) was used to identify significant differences between groups considering each thematic category (i.e., service).

4. Results

4.1. Unveiling Current Place Management Priorities of UK BIDs

BIDs in the UK have been performing multifaceted roles on behalf of the levy payers and advocating the interests of the area (

Table 1). Our results show that cleaning-related services have moderate thematic relevance in the business plans currently in force in the former UK pilot BIDs. However, most BIDs indicate that street washing/disinfection and, albeit to a lesser degree, waste collection/management are key operational activities at present. For example, Better Bankside BID provides street jet washing services in order to remove street drinking detritus. Some disinfection services have recently been expanded due to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as public touchpoints disinfection (Hammersmith BID). In addition, BIDs are also fairly involved in public realm investments aimed at improving the ‘business atmosphere’ of the BID area. The most common thematic references in this field include greening schemes (planting trees/shrubbery and installing pop-up parks), the placement of flower baskets and the investment in eye-catching lighting displays. In addition, nearly half of the BIDs recently reported their commitment to physical accessibility and mobility paradigms shifts in their current term, as We Are Waterloo BID clearly illustrate. While this may be due to street repurposing investments, such as pavement improvements and pedestrian areas creation (e.g., Paddington and New West End Occupier BIDs), it may also expose environmental sustainability concerns that most BIDs currently show. For example, while enhancing accessibility to the BID area, some BIDs are also improving bicycle parking provisions and bike racks (e.g., Newry, Plymouth and We Are Waterloo BIDs) and promoting the creation of ultra-low emission areas (e.g., Hammersmith and Heart of London West End BIDs). Finally, still in the ‘clean, green and safe’ mantra, BIDs show extensive concerns about security and safety services to ensure anti-social behavior is sanctioned and excluded from the BID area. That is achieved through the daily presence of patrolling teams (street ambassadors and street police officers), surveillance technologies (CCTV, Shopwatch and ANPR) and ‘Behave or Be Banned’ schemes.

Security and safety, capital improvements and cleaning-related services have been complemented by a wide diversity of consumer and place marketing activities. On the one hand, around 90% of former UK pilot BIDs reported that the offer of ‘value for money’ experiences is a central element in their current management operations both at day- and evening economies. In broad terms, the organization of annual events during festive seasons, such as Carnival, Easter and Christmas, is the most referenced consumer and place marketing service in current business plans. In addition to outdoor cinemas, regular live music shows and art exhibitions, some BIDs offer opera performances (Hull BID), pilates and yoga classes (Hammersmith BID) and more immersive and meaningful experiences, such as the well-known ‘spa in the city’ (Essential Edinburgh BID). On the other hand, current BIDs reveal a strong interest in promotional and advertising schemes aimed at changing visitors’ perceptions and creating the stamp that unforgettable entertainment experiences can only occur in the BID area. For example, by contracting professional public relations services, most BIDs focus on multi-channel destination marketing campaigns to retain and attract new consumer segments, including tourists, international students and investors (e.g., We Are Waterloo, Heart of London West End, Birmingham, Manchester and Plymouth BIDs). Similarly, several BIDs strongly invest in informative brochures and branded magazines distribution.

UK former pilot BIDs have also been performing a considerable role as influencers, lobbyists, and campaigners on behalf of levy payers, thus acting as local convenors and knowledge repositories. Firstly, current BIDs share information about structural market shifts through networking and training events. These events aimed at BID members often include information-sharing forums, business awards to showcase best practices in the BID area, mentoring programs and funding grants. For example, Inverness BID annually organizes the BID City Center Business Awards and several BIDs award funding grants to BID members (e.g., recovery grants during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of which with strong public sector involvement as in Scotland). Secondly, UK BIDs are increasingly powerful actors in urban politics as they voice the concerns and recommendations of BID members and ensure that they are discussed, negotiated and implemented at the highest level. Some examples consist of retail environment regulations, transportation developments and crime and safety partnerships. Thirdly, thematic references aimed at attracting and retaining businesses are often reported in the existing business plans. Such initiatives intend to reduce vacant shops through financial benefits to new or existing businesses in informative brochures and social events, such as ‘Enterprise Weeks’ or ‘Open Days’. Some BIDs are currently investing in business incubator initiatives to attract start-ups and pop-ups premises (e.g., Strabane, Newry, Lincoln, Paddington and New West End Occupier BIDs). Lastly, there is evidence that some BIDs (Bedford BID) are also promoting voluntary BID memberships to raise awareness about the benefits that non-BID members would have if they joined the BID.

The thematic analysis of the business plans currently in force shows that there are two under-represented placemaking dimensions. Firstly, BID action remains closely focused on the interests of the levy payers. Programs focused on the social and economic integration of vulnerable groups, such as homeless or panhandlers, are still poorly cited by existing BIDs. Manchester, Rugby and New West End Occupier BIDs are among the few exceptions that have professional homeless outreach services. Secondly, we found an emerging thematic trend associated with digital marketing programs. Although the overall relevance of these programs in the business plans currently in force is weak, some BIDs recently recognized that younger customers use the internet on a daily basis and usually ‘on the go’ (see Retail BID Birmingham). Unsurprisingly, these BIDs agreed to invest in their digital presence through easy-to-find digital channels, such as managing a website and creating social media networks for the BID and its members. These digital channels often host a free directory with the listing and geolocation of the existing businesses, promotions and entertainment activities. This suggests that BID’s digital professionalization creates a ‘window of opportunity’ to embrace new market segments. While some BIDs are currently investing in digital infrastructures (e.g., free Wi-Fi hotspots), the development of BID mobile apps is still little referenced in current business plans. Similarly, references to schemes that combine online and brick-and-mortar experiences are rare. However, it should be noted that two former pilots (Retail BID Birmingham and Hammersmith BID) have already recognized that digital shopping channels do not threaten the economic vitality and viability of traditional shopping districts since these two BIDs have recently started to invest in click and collect services.

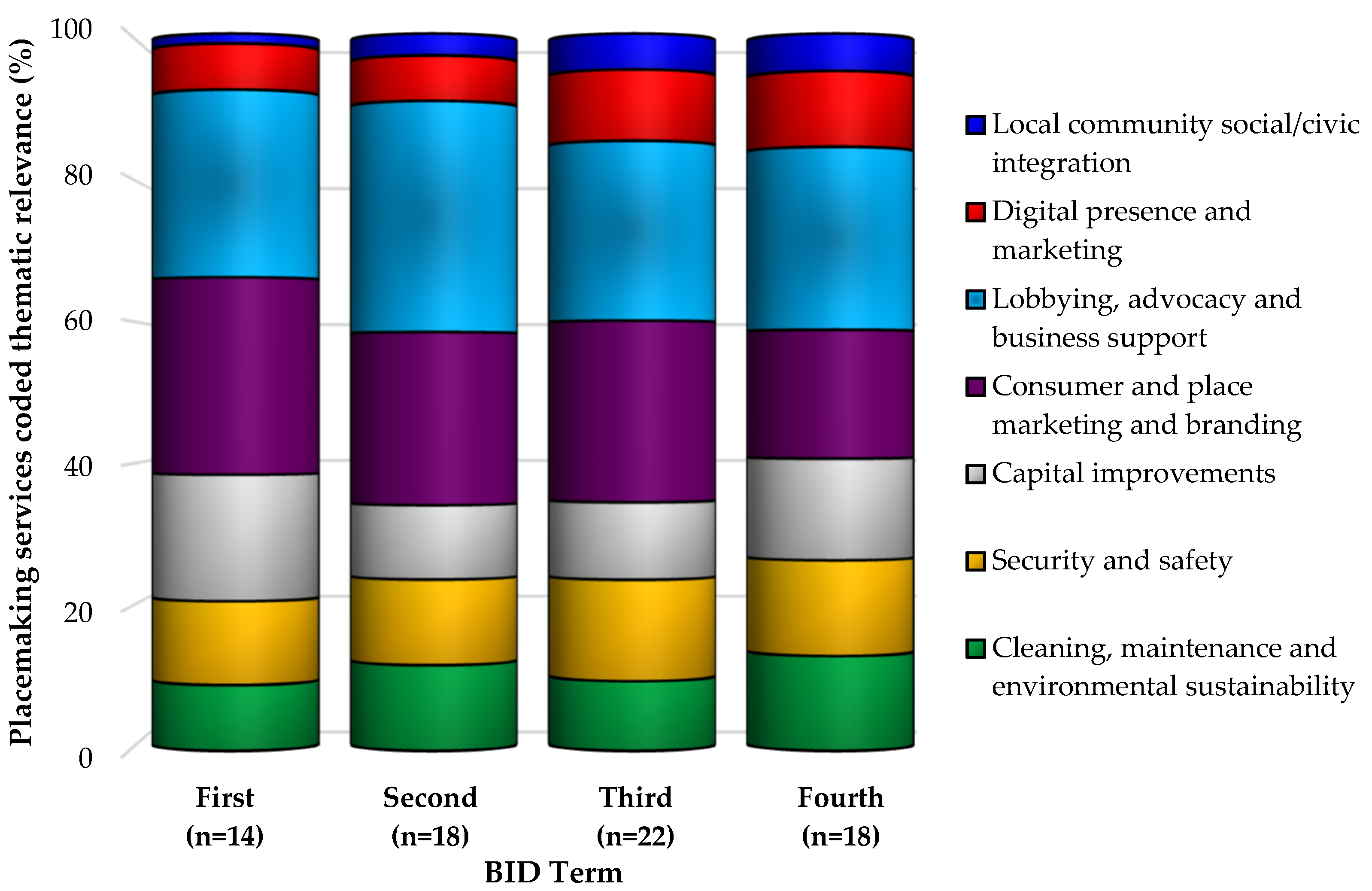

4.2. Following Longitudinal Evolution of BIDs as Services Providers

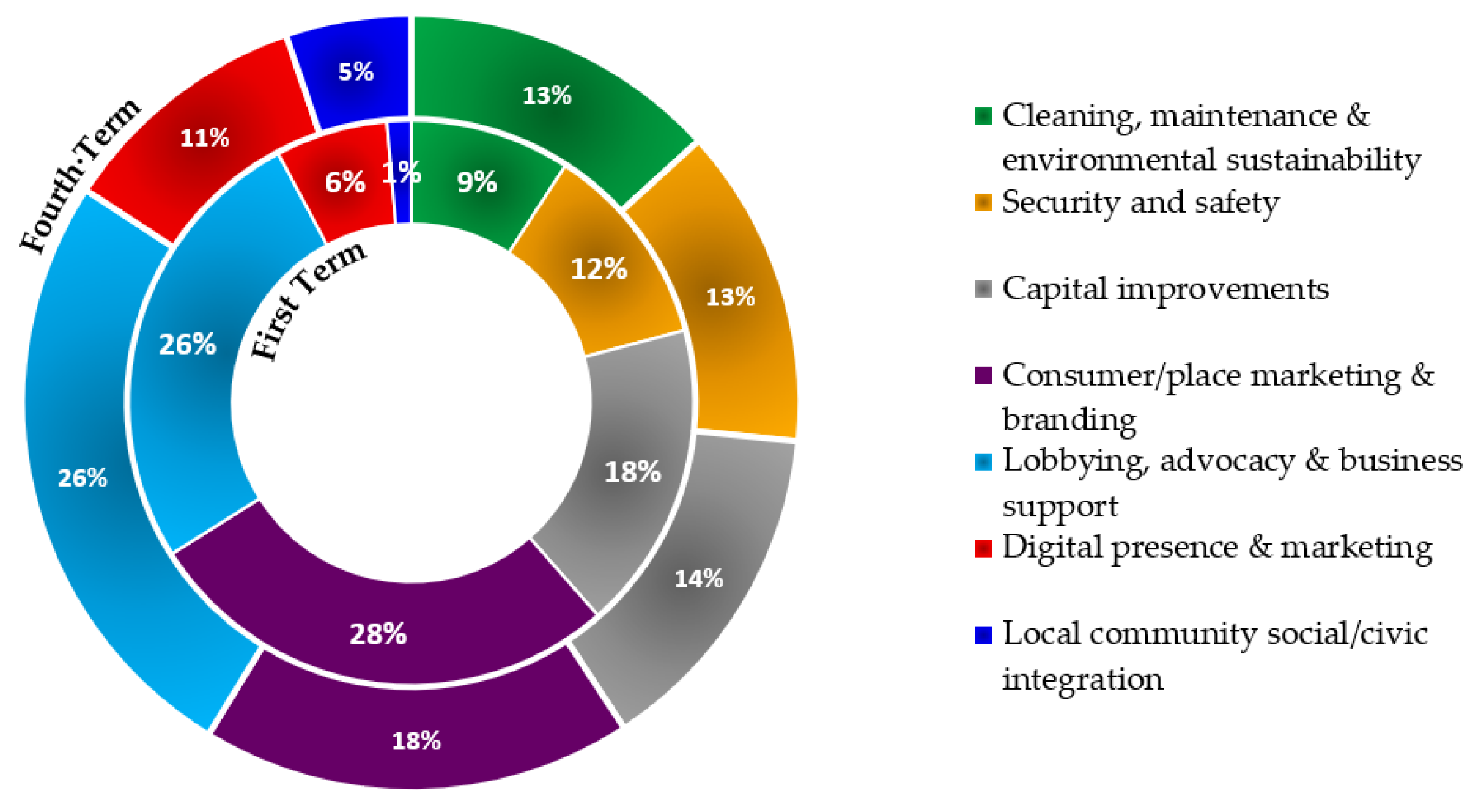

Since BIDs were territorialized in the UK 15 years ago (5 years ago in Northern Ireland), these local governance structures have not always delivered the same placemaking services. On the contrary, a detailed longitudinal analysis of the activities included in the BIDs’ business plans indicates that the strategic and operational activities of the former UK pilot BIDs have expanded as they have been democratically renewed. As we will discuss, BIDs have been embracing more complex projects and diversifying their areas of activity while continuing to provide elementary placemaking services (

Figure 4).

Firstly, our analysis shows that ‘clean, green and safe’ services recorded a small reduction in their thematic relevance between the first and third terms (−3.9%). However, recent evidence suggests that fourth-term BIDs have strongly invested in ‘clean, green and safe’ services since their overall thematic relevance increased by 6.5% when comparing the second- and fourth-term BIDs. Such evolution is due to a double process. On the one hand, the thematic references related to capital improvement activities, which peaked in first-term BIDs, have successfully reinforced their relative relevance between the second and fourth terms. In particular, BIDs seek to carry out more structural interventions in the public space. For example, while first-term BIDs invest more in decorative lighting, street furniture and remote monitoring devices (CCTV), fourth-term BIDs, in addition to the greening of the area, tend to focus more on mobility patterns through street repurposing projects. On the other hand, placemaking services related to cleaning, maintenance and environmental sustainability have also successively increased their overall relevance in BIDs’ business plans over time. First, maintenance and repair services, which have always been little cited, have strengthened their thematic relevance thanks to the maintenance services of green spaces (related to the overall investment in greening schemes) and miscellaneous maintenance services (e.g., additional on-street maintenance teams and new procedures for reporting defects in public space). The latter had a significant relation with the BID term (F (3, 68) = 2.88, p-value = 0.04), particularly when comparing first-term and fourth-term BIDs. Second, operational activities aimed at responding to environmental issues have shown a substantial increase over time (0.92% in first-term BIDs to 3.52% in fourth-term BIDs). This notable longitudinal shift stresses that BIDs have recently been more concerned about the impacts of existing mobility concepts on air quality and the need to frame new chrono-urbanism principles, such as the 15-min neighborhood. Therefore, BIDs at a more advanced stage often mention plastic/cardboard recycling services, investment in cycling infrastructure and electric vehicles and the creation of reduced emissions areas as operational priorities. However, although thematic references reached a relative peak in the fourth term, we noted that both second- and third-term BIDs also expose considerable concerns with sustainability issues (2.44 and 2.36%, respectively). For this reason, we found no significant relation between environmental concerns and the BID term at the 5% level (F (3, 68) = 2.38, p-value = 0.07). Third, security and safety services have not recorded pertinent variations in their thematic relevance over time. Though, it was possible to discern that third- and fourth-term BIDs tend to invest in disorder prevention and exclusion schemes while first-term BIDs prioritize patrolling teams and public space improvements to deter crime.

Secondly, consumer marketing and place branding services have recorded successive declines in their thematic relevance in the former UK pilot BIDs’ business plans. While these services expressed about 25% of the thematic references in the first-, second- and third-term BIDs, this figure dropped to 18% in the fourth-term BIDs. This longitudinal change is partly justified, on the one hand, by the massive reduction in promotional and advertising campaigns references (14% in the first term and 7.52% in the fourth term) and by the decrease in the number of activities related to evening- and night-time economies, such as ‘Alive After Five’ programs (3.21% in the first term and 0.73% in the fourth term). Similar to what has happened with the BIDs’ patrolling teams, welcoming services, including ambassadors’ teams, have also lost their thematic relevance throughout the terms. However, we noted that experiential marketing—which aims to engage consumers and invite them to immerse themselves in the BID brand through high-quality animation events and distinctive promotional/branding campaigns—is still the leading consumer and place marketing strategy. On the other hand, the decline in consumer marketing and place branding services, particularly between the third- and fourth-term BIDs, may also relate to the rise of digital channels that complement existing BID’s experiential marketing strategies. We will discuss this argument further when introducing how online channels have impacted BIDs’ operational activities. Finally, ANOVA results found no significant differences between consumer and place marketing/branding services and the BID term.

Thirdly, former UK pilot BIDs have been giving great importance to lobbying, advocacy and business support services throughout all terms (a stable thematic relevance of about 25% in all terms, except in second-term BIDs). On the one hand, BIDs have become key actors in urban politics because they have been vocalizing the concerns and interests of BID members over time. In addition to lobbying to lever in additional funds for major public realm improvements, such as street repurposing schemes, revitalization programs and transport and access developments, BIDs have been actively influencing all decision making that shape the future of the BID area on issues such as retail planning/licensing, accessibility/parking and security. Moreover, BIDs have also become key partners of several organizations (city council, police, community-based organizations, etc.) to promote mutual benefit synergies and ensure that statutory services are effectively delivered. On the other hand, BIDs have also been working as information repositories and training centers, particularly after the second term. Thereby, BIDs organize regular business meetings and accreditation sessions on issues that may affect business performance and customer experience. These events provide professional business advice on issues such as customer care, crime prevention and marketing strategies while sharing information on major improvements, consumer behavior and funding grant opportunities. Lastly, BIDs have also been promoting business-to-business networking events aimed at sharing best practices through local mentoring projects. Nonetheless, as the thematic relevance of lobbying, advocacy and business support has remained continuous over time, ANOVA results did not disclose any significant relation between these services and the BID term.

Fourthly, our findings show that BIDs have progressively engaged with community support services to tackle antisocial behavior and create a strong (and healthy) sense of community in the BID area. The thematic relevance of these services increased from 1.4% in first-term BIDs to 3.1% in second-term BIDs and about 5% in third- and fourth-term BIDs. On the one hand, BIDs’ civic role has focused on promoting multidimensional well-being initiatives (0.92% in first-term BIDs and 1.94% in fourth-term BIDs) and employment and training schemes (0.23% in first-term BIDs and 1.58% in fourth-term BIDs) aimed at BIDs members and the local community. While the former include child safe and first aid (defibrillators) initiatives and healthy lifestyle programs, such as yoga, mental health awareness, mindfulness courses, cycle training and smoking cessation clinics, the latter comprise meaningful local employment support programs that encourage BID members to provide working experiences for local residents and early school leavers as well as partnerships with local universities to expand employability skills qualifications and training courses. Unsurprisingly, our analysis showed that community employment and training services had a significant relation with the BID term (F (3, 68) = 3.05, p-value = 0.03), and the most significant differences were found between first- and third-term BIDs and first- and fourth-term BIDs, thus suggesting that these services are more easily found in BIDs at more advanced development stages. On the other hand, BIDs’ social services aimed at the socio-economic integration of vulnerable groups, including through local charities support, have been little mentioned in the business plans. Such evidence should be critically examined since, in addition to the weak thematic relevance of these services, there has been an increase in the number of references related to socio-economic exclusion schemes over time.

Finally, one of the main findings of the longitudinal thematic analysis is the advent of a new category of services hitherto absent from the literature on BIDs: digital presence and marketing. While the thematic relevance of these services has been experiencing successive increases, rising from 6.4% in first- and second-term BIDs to 10.6% in fourth-term BIDs, digital presence and marketing services are still an underrepresented thematic category in most business plans. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the thematic relevance found in first-term BIDs (6.4%) stems from the fact that Northern Ireland’s pilots started their operations in 2016 while the remaining pilot BIDs were set up between 2005 and 2008, which suggests that digital marketing becomes an operational priority depending on BIDs’ formation date rather than its term. Nonetheless, even removing Northern Ireland’s pilots from the analysis to ensure consistency of results—which resulted in the reduction of the thematic relevance of digital marketing services from 6.4 to 3.2% in the first term—significant relations between the digital presence and marketing services and the BID term were found in both analyses. First, while website creation and management both for the BID area and each levy-payer has remained as one of the essential operational activities over time, our analysis indicates that the BIDs’ presence on digital platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram and Twitter) had a significant relation with the BID term (F (3, 68) = 3.23, p-value = 0.02). These results expose that BIDs are increasingly aware of the role that their ‘virtual presence’ has in how town centers and high streets are experienced by born-digital consumers, particularly between the second and fourth terms (p-value = 0.05). Second, in addition to their presence on virtual platforms, some BIDs have developed their own mobile apps to improve customer experience through real-time dissemination of pertinent business information, promotional campaigns and entertainment events. While the number of BIDs exploring mobile apps as digital shopping channels is still low, ANOVA results showed a significant relation between the launch of mobile apps with the BID term (F (3, 68) = 4.07, p-value = 0.01), with significant differences found between first- and third-term BIDs (p-value = 0.01). Third, our findings also indicate a significant relation between the provision of click and collect services and the BID term (F (3, 68) = 3.07, p-value = 0.03) with variations found between the first and third terms. In contrast to the claim that digital channels threaten the economic vitality of town centers, these results show that some BIDs have recently found that digital shopping methods—which allow consumers to browse and buy online and choose to collect their products in the BID area—are a ‘window of opportunity’ because it allows traditional shopping districts to embrace new shopping behaviors and bring multi-channel shoppers back into the district.

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The paper opened with a discussion of how two of the most influential forces of retail change—decentralization and digitalization—have undermined the vitality and viability of traditional urban commercial ecosystems and conceptualized BIDs as sub-local place management organizations aimed at responding to the contemporary challenges that town centers and high streets currently face. Building on this problematization, the paper has aimed to examine the evolving nature of the operational activities that former UK pilot BIDs have provided as place management organizations over the past 15 years. Through an exploratory sequential research design that combined a qualitative and quantitative thematic analysis of BIDs’ business plans in different temporal settings, we have shed light on how UK BIDs seem to describe a different, non-linear operational framework as placemaking services providers when compared to some of their US and Canadian counterparts. Our analysis has also made the case that digital marketing services have emerged as a new thematic category of place management practices in which BIDs have been investing in more recent terms, although only a few have embraced different digital endeavors beyond the modest presence in website and social media platforms.

In drawing this study to a close, the results of this paper make six important contributions both to the place management and BID-related literature and to place management practitioners, in particular BIDs’ managers. The first contribution is that UK BIDs have not strongly prioritized basic placemaking services, such as ‘clean, green and safe’, in their early operations. While none of these three categories was the most relevant when analyzed independently, the empirical analysis has also shown an increase in the thematic relevance of ‘clean, green and safe’ services in fourth-term BIDs due to the rise of environmental sustainability issues. Therefore, these results do not support insights from existing North American-centric BID literature which has broadly argued that cleaning, maintenance and security services, in addition to shape the main early priorities of most place management organizations, tend to experience consecutive thematic reductions over time [

53,

56,

58]. These differences may be due to, on the one hand, the time gap between the flourishing of BIDs in the US and the UK, so that the original basic needs of town centers were different. On the other hand, it may be the case that local government involvement in the UK is more effective and efficient in the delivery of statutory services, such as urban cleaning/maintenance, so there is no such substantive need for the BID to strongly invest in these kinds of services [

26,

49,

72].

The second contribution is that UK BIDs have been central actors in urban politics since their first term. According to the existing literature, BIDs were expected to disclose their role as political lobbyists at more advanced ‘life stages’ and often after the effective delivery of placemaking services such as cleaning and security [

53,

56,

58,

66]. However, UK BIDs have acquired a strong level of political influence since their inception. While the formation of US BIDs is more dependent on the private sector initiative [

36,

37,

71], local and central governments in the UK have sponsored the creation of BIDs through the introduction of pilot initiatives (National BID pilot project, ‘The Circle Initiative’, Scottish Pathfinders and Northern Ireland BID Academy) [

30,

42,

79,

80]. For example, the Scottish government has been funding Scotland’s Improvement Districts to build a national-based organizational capacity to support the creation of BIDs through the empowerment of strong partnerships between public, private, third sector and community associations. It is unsurprising that the institutionalization of a spirit of long-lasting collaboration between public and private sectors (and third sector, particularly in Scotland) in matters of town center management has translated into a strengthening of the political influence that BIDs are given on place-shaping issues, in particular how structural capital investments and legislative regulations are discussed, negotiated and locally implemented [

23,

34,

50,

66].

The third contribution is that marketing and place branding services in the UK BIDs have not increased their thematic relevance over time due to the reduction of thematic references in promotional/advertising campaigns. Considering this evidence, two considerations can be drawn. First, previous conceptualizations that considered that marketing services focused exclusively on the production of knowledge to know consumers’ habits and needs proved to be limited frameworks to understand how UK BIDs operate [

58]. While BIDs recognize the importance of mobilizing such knowledge in the design of customer loyalty programs, most BIDs prioritize experiential marketing services, such as street animation, special events and promotional and advertising campaigns in which the consumer becomes an active subject in the production of the BID brand. Therefore, it is not exactly the process of gathering information, but its practical use towards the political and experience economy of place that stands out in BIDs’ operational activities [

28,

52,

64,

65]. Second, the longitudinal reduction in the thematic relevance of experiential marketing activities should be critically examined considering that such a decrease may be due to the transfer of parts of experiential marketing services and budgets towards virtual extensions. For example, Coventry BID stated in its 2013–2018 business plan that “[the BID] would look to shift a large proportion of the marketing budget towards [its] digital presence” (p. 23). Further research inquiries should closely examine this evidence.

The fourth contribution, which derives from the three previous arguments, is that linear and unidirectional frameworks are not adequate to understand how place management organizations have performed and evolved over time. Findings showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the provision of most placemaking services and the BID term, which allows us to draw two main considerations. First, while some exceptions were found (e.g., digital presence/marketing and community employment/training services), UK BIDs did not disclose in their operational activities that some placemaking services were only found in a specific BID term. Second, the longitudinal analysis also showed that the thematic relevance of the different placemaking services was constant among the BID terms. For these reasons, while recognizing that the condition of the town center, the BID budget and the degree of participation of the local government in urban management can explain why BIDs may start their operations by ‘upper place management bands’, this paper is reluctant to support insights from previous studies that have broadly suggested that ‘clean and safe’ programs are always initial priorities while lobbying and advocacy services are easily found in later stages [

39,

53,

55,

56]. Therefore, we argue for a new non-hierarchical and non-linear theoretical and practitioner framework that recognizes that BIDs have diversified the placemaking services they offer without ever replacing them (

Figure 5).

The fifth contribution is that there has been a noticeable thematic growth in the operational activities aimed at introducing ‘socioeconomic hygiene practices’ within the BID area [

62]. While we found an increase in the number of operational activities related to the socioeconomic integration of vulnerable groups in latest business plans, like previous studies reported [

53,

57], the thematic relevance of such social services in UK BIDs is still modest. Concurrently, crime prevention and exclusion order schemes introduced to remove transgressive and informal behaviors from the BID area have substantially increased their thematic relevance in recent terms [

61,

63,

64,

65]. This evidence shed light on how BIDs’ operational practices seem to be making increased use of surveillance capitalism tactics to enhance the ‘place coolness’ and ‘business atmosphere’ of the BID area [

28,

31,

52]. Ultimately, these operational activities may lead to a new space production resulting from the praise of a placemaking approach that contributes to the rise of non-inclusive and private spaces (e.g., CCTV and ‘Behave or Be Banned’ schemes), as suggested by previous studies [

49,

50,

51,

62,

63,

64,

65].

The sixth and last contribution is related to the advent of digital marketing services in BIDs’ business plans and the outcomes these activities have in BID management politics and in how born-digital consumers experience traditional shopping districts. In this instance, while the website and social media presence overlap all BID terms within the scope of digital marketing services, findings also suggested that only a few BIDs (e.g., Retail Birmingham and Hammersmith) have invested in additional digital marketing services, such as mobile apps and click and collect services. Therefore, most BIDs have not yet completely embraced virtual world assets as powerful means in fostering the competitiveness and resilience of town centers and high streets in the digital age. While some theorized digitization as ‘the death of the high street’ (brick-and-mortar businesses) [

90], we argue that digital channels, which remain largely unexplored by BIDs, provide a ‘window of opportunity’ for the vitality and viability of town centers and high streets. Although traditional brick-and-mortar stores can hardly compete with online retailers in terms of operating costs and consumer convenience, such stores should create meaningful experiences both in the physical realm and the virtual space as the latter is where technophile consumers interact and experience the high street [

10,

12,

13,

91]. Therefore, we contend that BIDs should reinvent their management approaches to create places of phygital shopping experiences blending in a balanced way the assets of both physical and virtual worlds. Through the conception of phygital shopping environments, digital placemaking becomes a prosthesis of the physical realm, transforming shopping districts into a set of click-and-mortar premises with reported increases in in-store visits and customer loyalty and engagement [

92]. Although experiential phygitalization and in-store digital placemaking are already flourishing in some high streets and town centers—namely led by technological corporations, such as Amazon, Google and Samsung, and international fashion brands –, BIDs and their members also have a lot to benefit from staging memorable phygital experiences [

91,

92,

93]. For example, bringing an online shopping experience to offline retail through virtual reality allows customers to interact with products in physical spaces while having access to online shopping features, thus enriching customer experience and making shopping more connected, social and immersive [

94].

The need for a repositioning of the BID areas management paradigm towards the creation of phygital shopping experiential destinations has been recently advocated by both academics and practitioners. While some have highlighted the role played by the experience economy, evening and night-time economies and the dichotomy between physical town centers and digital high streets [

17,

64], others have emphasized the power of hybrid consumer environments, blending the digital, physical and social realms, to improve the attractiveness, localness and resilience of town centers and places [

95,

96]. In short, phygitalization of shopping experiences and places may well become a new challenge for BIDs, but they are also their main differentiating asset towards thriving high streets and town centers.