1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed an unprecedented economic and social crisis [

1,

2], highlighting what was announced at the beginning of the 21st century: the fragility of contemporary capitalism and the permanent crisis of globalization [

3]. At the social level, in just a few months there has been an increase in inequalities on all geographical scales at global, regional, and metropolitan levels [

4,

5]. Thanks to the conditions of the technical scientific informational environment [

6], there has been a process of concentration of capital that has meant the destruction of millions of jobs [

1]. More employment destruction than during the Great Recession (2008–2011), as indicated by the International Labour Organisation [

7]. All indications are that the COVID-19 crisis has further deepened the contradictions of the capitalist system [

8]. The collapse of the system in 2008 has already made us plan for its very viability [

9,

10]; in 2021, even more so. Trading and retail activities are a key stage of distribution to sustain globalization [

11]. As the effects of COVID-19 are a crisis of globalization, trading activities and retail have undergone many transformations. The transformations have meant the acceleration of some of the processes that had been occurring since the Great Recession (2008–2011), all of which are interconnected. We can identify the following: (a.) concentration of capital around fewer and fewer companies in the retail sector, (b.) increasing and deepening the virtualization of commerce, (c.) increasing dependence on logistics, (d.) more shop closures than openings, and (d.) job destruction.

On a global scale, the so-called “pure players” have been rapidly acquiring more and more capital. For example, Amazon has been considered a monopoly by the US Congress since October 2020 [

12], and according to the Fortune 500 ranking, it has risen from 26th to 9th place in just three years (2017–2020). Something similar happened with Aliexpress, the Chinese ecommerce giant, which moved from position 462 to 132 during the same period. On a Spanish scale, large-scale distribution companies such as Mercadona and INDITEX continue to maintain their hegemony or improve their position. In both cases, this was thanks to the improvement of their virtual marketplace.

The virtualization of the retail sector has led to a massive destruction of jobs in the street retail sector with the consequent closure of stores [

13], especially in 2020 and 2021. In Spain, between 2020 and 2021, global companies have announced the layoff of thousands of workers and the closure of hundreds of stores and department stores: H&M (1100 workers, closure of 30 stores during 2021 in Spain), Corte Inglés (4312 workers, closure of 3 department stores), Mango (4700 employees), or Amancio Ortega’s holding company, INDITEX (987 employees, closure of 400 stores). All of the workers have not been reintegrated into the delivery service companies, which are growing in parallel with the rise of ecommerce. To these redundancies must be added the definitive closure of thousands of family-run retail establishments, especially those that do not own the retail premises in which they were located. In the US, a total of 12,200 shops are believed to have closed in 2020 and will never reopen [

14]. In the restauration sector, during the first 10 months of the pandemic, a 20% reduction in employment was identified (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica de España) without counting staff who were out of work, but with social benefits. Probably the most important landscape change has been the massive desertification of commercial fabric (retail and services). These dynamics threaten the very vitality of the street. If the crisis occurs in the center of the city, symbolically, it seems as if the whole city is in crisis [

15].

The logistics revolution has provided a spatial solution to the chronic problem of the over-accumulation of capitalism since the crisis of the 1970s [

16,

17]. The logistics revolution is motivated by large investments in land infrastructure and the information technology revolution (since 2017, 5G technology). This revolution has made it possible to accelerate the virtualization of commerce. Consequently, ecommerce should be interpreted as one of the vectors of the refoundation of capitalism that emerged from the 2008 crisis in the light of neoliberalism (Amazon was founded in the USA in 1994 and, in 2021, it is the second most important retail company in the world, according to Deloitte). Thus, the modernization of distribution, incorporating both logistics and retail, which acts by connecting consumption with the product, has made it possible to sustain the productive system [

11,

18].

As discussed above, the current crisis is an acceleration of what began to be detected from the 2008 crisis onwards, especially in the USA. In 2008, the financial crisis meant a very significant loss of jobs in the retail sector, with 1.2 million jobs out of a total of eight million being destroyed in two years in the US [

19]. The retail crisis particularly affected the clothing sector but also shopping centers, where demalling began. Subsequently, this process has spread throughout the world with different rhythms, intensities, and forms, as can be seen in the case of Portugal [

20], or identified for the peripheral municipalities of the metropolitan area of Barcelona [

21,

22]. Between 2014–2017, millions of real estate assets in the retail sector were massively devalued, especially those located in less central areas of the metropolis, forcing hundreds of shopping centers that had been built before 2007 to close following the logic of the second circuit of capital accumulation [

23]. On the supply side, the sector was unable to cope with heavy debts due to strong competition from the online channel and improved logistics. On the demand side, the significant decline in consumer purchasing power [

24] did not help retail companies either. Consumer preferences changed rapidly, with consumers seeking to consume more places and experiences [

25,

26,

27], a fact that strengthened urban tourism [

28,

29]. In a context of generalized crisis in the retail sector, tourism strategically positioned well-located commercial companies, especially those in the city center. Journalists used the words retail apocalypse, used for the first time in 2017, to designate this whole process that had been operating since 2014 in the USA, which in short meant that more shops were closing than opening [

19].

In the middle of this recessionary context of the commercial fabric [

30,

31], the retail and services activities of city centers adapted rapidly and massively to tourist demand. This demand was more solvent than local demand, which is particularly impoverished and greater [

32]. The adaptation of retail to a global tourism demand means a scale jumping [

33] made it possible to maintain the retail dynamism of city centers. There is a high level of store closures in urban centers that are not global tourist centers [

15,

32]. In fact, the capture of tourist demand became a retail adaptation strategy (resilience) in a generalized context of the neoliberal crisis in retail sector.

Tourists do not consume online. Unlike local consumers, who are more impoverished and who are concentrating their consumption in increasingly cheaper establishments, increasingly in the online channel, with the exception of foodstuffs. The tourist predilection for the city center generates the concentration of retail activities in this part of the city. This is especially relevant in European cities, where the center is usually a place of high heritage value, and occurs more in southern European cities, where the economic specialization in tourist demand is very high. Barcelona is a good example of tourist specialization, especially if one also takes into account that it is not a state capital [

34].

Much of the literature linking commerce and urban tourism has focused its analysis on the unsustainability of tourism and on criticizing the lack of respect for the community and local retail [

35]. The replacement of retail activities serving local residents with those serving tourists has been linked to retail gentrification [

36]. Some of this research has focused on changes in municipal markets [

37,

38] and high streets [

30]. It specifies that the traditional retail that residents need for their daily lives is disappearing. In this sense, it is stated that: “popular markets are turned into tourist attractions, fruit shops disappear and ice-cream parlors open in their place. This is a daily pressure that complicates the life of the local population” [

39] (p. 301). Two years later, in 2021, it is stated that “the change in retail implies that residents need to walk to other neighborhoods to access daily products, which is a significant disruption for the elderly and for people with children as the overcrowding of public spaces makes it increasingly difficult for them to move around.” [

40] (pp. 12–13).

The tourist specialization of the city center has been addressed from the perspective of goal 11 of the Sustainable Developments Goals: “Sustainable Cities and Communities”. This objective relates to the concept of retail resilience. It is defined as: “the capacity of different types of retail at different scales to adapt to changes, crises or shocks that challenge the balance of the system, while continuing to fulfil their functions in a sustainable manner” [

41] (pp. 19–44). The current context of the mass closure of retail establishments calls into question the operability of the very concept of retail resilience. The creation of online marketplaces can be an action to support the resilience of the retail trade. However, retail desertification will continue to spread, calling into question sustainable development goal 11.

The rescaling of the city center, thanks to international consumption, adds to the already theorized process of the recentralization of consumption on a metropolitan and regional scale [

40]. Before the pandemic, the dynamism of retail activities was characterized, first, by the global concentration of consumption due to global tourism and the recentralization of consumption on a metropolitan scale. This recentralization has led to a loss of dynamism in peripheral shopping centers and a crisis in the retail structure of neighborhoods. Barcelona’s neighborhood retail, for example, is dominated by highly capitalized small/medium places (less than 2500 square meters). These are retail places classified as food sector, but which also offer household goods, clothing, and accessories.

Despite the predominance of the traditional center in European cities, the emergence of new centers has linked consumption points to the overcoming of the traditional center-periphery dynamic [

31,

42]. These are new centers linked to restauration/pubs and leisure and not to more advanced services, as is the case for the Central Business District (CBD).

The

scale jumping of city centers, based on the attraction of tourist flows that are organized in networks on a global scale, breaks with the idea of the existence of a center with a periphery, as in many traditional urban theories [

33]. The Chicago school, the Alonso theory of income function, Chirstaller’s theory of central places and its derivative reformulations by Bryan Berry and Lösch, and even the theory of gentrification, have all taken the centrality of the CBD as a starting point to explain the city as a whole. It is necessary to carry out a multi-scale analysis that takes into account many other scales that go beyond the traditional limits of the city. The proposal of a global city based on the attraction of global consumers would complement the widely held idea of global cities from a geoeconomical perspective [

43].

This process forces us to rethink the traditional conception of center–periphery dynamics. It is necessary to rethink the thesis of the existence of a center that is not structured on the basis of a periphery or a traditional hinterland, but on the basis of a global scaling up of consumption. A rescaling which, in the light of the rise and fall of international tourism, allows us to analyze the process both upwards and downwards. On the basis of this thesis, the traditional logic of the theories of urban retail and the city of industrial capitalism have also broken. The proximity of consumers and the threshold, defined as the number of consumers needed to support a good, does not explain retail hierarchy. In this case, the threshold has no boundaries but become global networks. It seems more appropriate to be facing an urban restructuring based on a series of implosions and explosions of the urban phenomenon affecting all spatial scales [

44] (p. 305) in a global moment of differential urbanization [

45]. The closure of retail activities, directly related to the end of global consumer flows, make retail activities useful variables for the analysis of the rescaling of urban spaces.

The aim of this article was to analyze the effects of COVID-19 on the retail structure of Barcelona through the closure of establishments. The specific quantitative hypothesis tested here is that, relative to the period 2017–2019, the proportion of closed stores will be significantly larger after the pandemic in 2021. It is also hypothesized that this proportion will be higher in the tourist commercial axes of the center than in the neighborhoods. Special emphasis is placed on the city center. It analyses, on the one hand, the Central Business District (Passeig de Grácia) with its luxury shops, and, on the other hand, the historic center, specialized in global tourist consumption (Carrer Ferran). The work aimed to present the adaptation of commercial activities to global tourist demand as a strategy for the resilience of street-level retail. This fact is important to highlight in a context in which, while local consumption is increasingly concentrated around online retail, tourist consumption is clearly offline. The role of tourism as a driver of street-level retail contrasts with the traditional critical urban studies that blame tourism as the main cause of shop closures.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper was based on the experience of more than twenty years of urban and retail studies within the research group of the Retail Observatory of the University of Barcelona (OCUB) [

15,

46,

47,

48]. It is important to note that there are no statistical databases on commerce activities (retail and services) that would allow us to address the research objectives. The only exception was the data from Perfil de Ciutat [

49]. In order to know the retail activities before and after the pandemic at the street and house number, as well as the type of demand to which it was directed, it has been necessary to resort to fieldwork.

The fieldwork was carried out between October 2017 and May 2021, including seven semi-structured interviews with stakeholders or privileged informants involved in retail activities in the city during COVID-19 (

Table 1). The interviews were complemented by 20 formal direct observations in the main tourist axes (Passeig de Gràcia, Diagonal, Plaça Catalunya, Rambla Catalunya, Las Ramblas, Portal de l’Àngel, Carrer Jaume Primer, Barri Gòric), shopping centers (las Arenas, Glòries, la Maquinista, Illa Diagonal), shopping districts (Sant Antoni, Cor Eixample, Nou Eixample, Eix Comercial del Raval, Sant Martí Eix Comercial) and municipal markets (Ninot, Sant Antoni, Sans, Hostafrancs, Galvany, Sagrada Família and Besós).

In-depth fieldwork was carried out on Passeig de Gràcia, Carrer Ferran–Jaume I, and La Rambla. Various fieldwork campaigns have been conducted since 2017. The fieldwork in 2020 and 2021 was carried out when the regulations allowed the opening of the establishments, thus identifying the premises that were without tenants. For the cases of the Paseo de Gracia and Ferran, the data obtained from the fieldwork have been treated cartographically to identify the commercial fabric and better understand the functioning of the street. To compare the proportion of commercial establishments that were closed before and after the pandemic, a Chi-square test was performed using the prop.test function in R version 3.6.3 [

50]. This same test was used to compare the number of establishments closed before and after the pandemic between retail zones.

The fieldwork has been complemented by an analysis of recent news items from the main Barcelona newspapers (La Vanguardia, El País, El Periódico) as well as informal discussions with stakeholders during the period of the pandemic.

3. Retail Structure in Barcelona: From Tourism-Phobia to the Desertification of City Center

Barcelona has been the world’s main urban laboratory of tourist specialization, despite the numerous studies that have also dealt with the excesses of tourism in many cities, such as Palma de Mallorca, Granada, Valencia, Madrid, Venice, Lisbon and Malta [

51]. Barcelona is the city with the highest concentration of publications on the subject, where most urban conflicts were identified, with frequent slogans on walls such as “tourism kills neighbourhoods” or “guiris go home” (tourists go home). As if that were not enough, the city’s mayoralty since 2015 has been held by a political coalition clearly opposed to mass tourism, Barcelona en Comú.

The focus on the negative effects of tourism has also had its own loudspeaker in the press with the concept of tourism-phobia, which has become a “buzzword” in the mass media. The term was first used in 2008 in an article by Manuel Delgado in the newspaper

El País [

52], which referred to the substitution of the local working class by a new tourist class. Since then, it has appeared a total of 223 times in newspaper articles in Barcelona’s most massive newspaper,

La Vanguardia. Above all, it has been used to refer to the responses and conflicts caused by tourism. In the academic world, the concept of overtourism, understood as the impact of tourism on the destination, has become widespread [

53,

54].

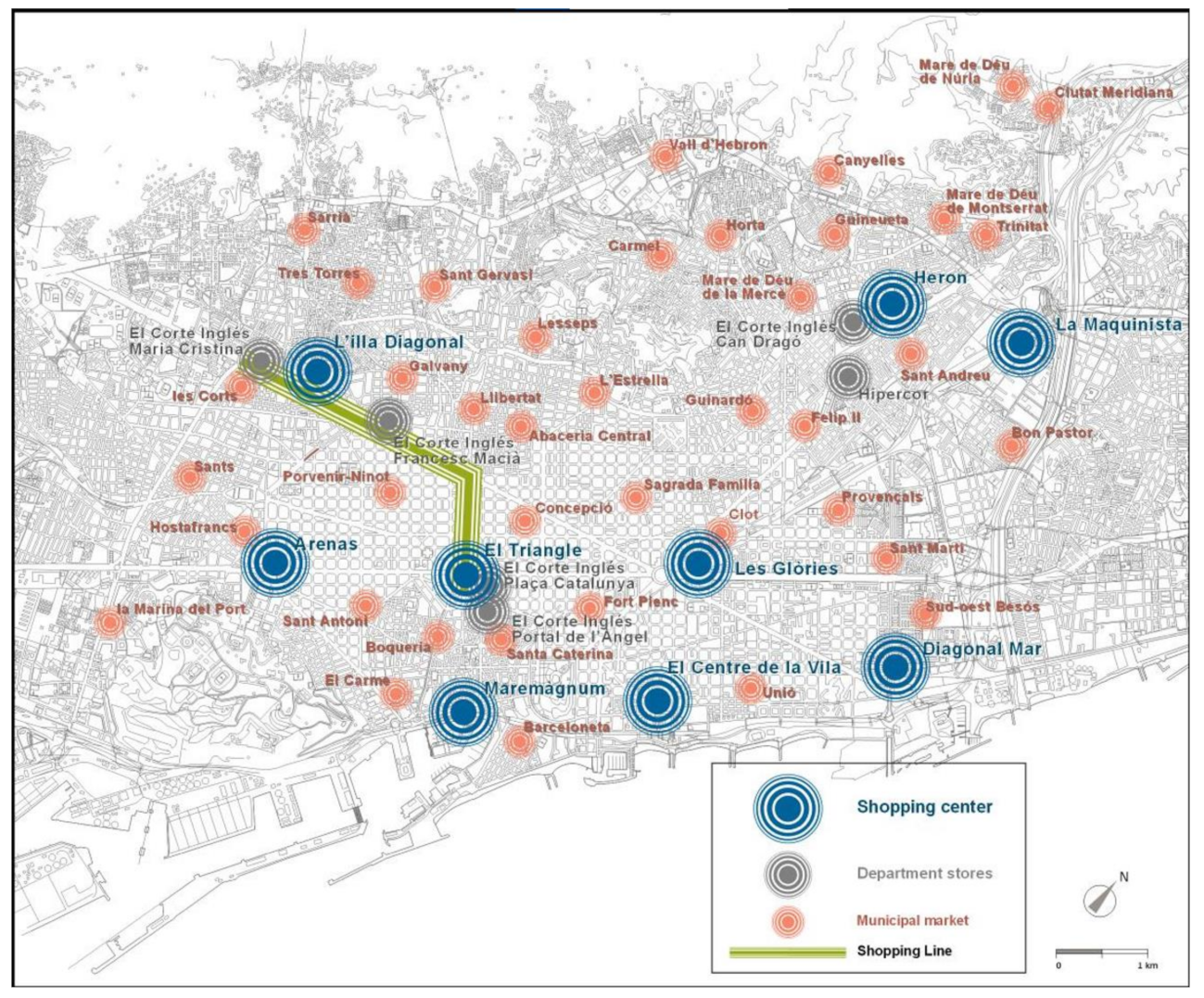

Figure 1 is intended as a summary map of the city’s retail structure, with the location of Barcelona’s current main shopping centralities at the end of the second decade of the 21st century. The network of municipal markets represents the first level of Barcelona’s retail structure. The municipal administration has promoted transformations to promote their resilience since the 1990s, with mixed results. Supermarkets have been incorporated on the lower floors, restaurant space has been increased and those still more centrally located have also adapted to tourist demand [

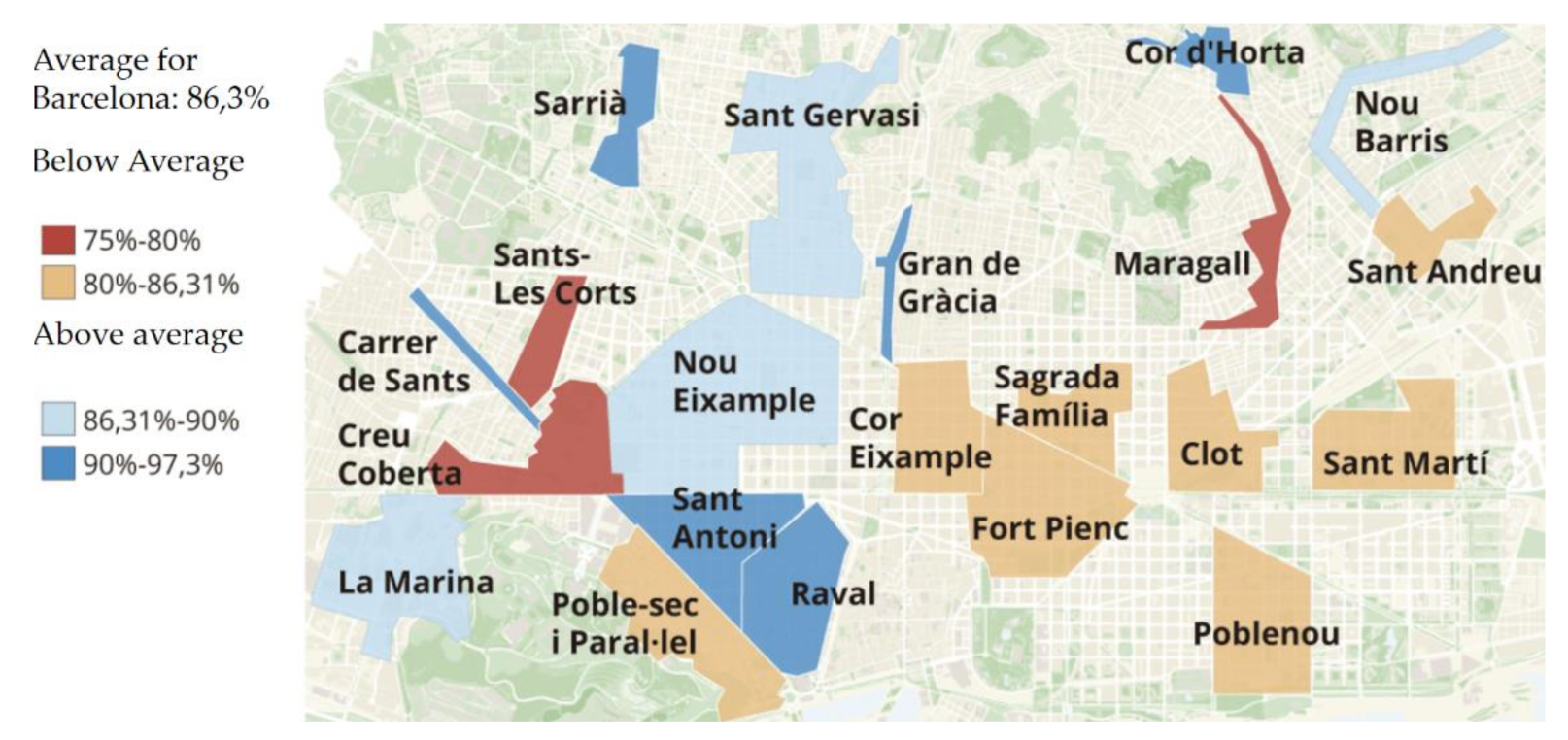

55]. The myriad of unrepresented shops of the defined first level, organized around the municipal markets and other shopping centers, has decreased drastically over the last 10 years. Many shops have been left empty and many others have changed their use, mainly to residences. This retail desertification had already started long before the 2020 pandemic, especially in non-core retail districts and neighborhoods (

Figure 2). According to the data of Ajuntament de Barcelona (2016), it can be seen that in the tourist and city center districts (Eixample and Ciutat Vella), as well as in the districts with the highest consumption capabilities (Sarrià-Sant Gervasi and Les Corts), the vacancy rate is lower than in the peripheral districts (

Table 2). Residents’ consumption, firstly, has become concentrated around a few highly capitalized retail operators, who locate their establishments closer and closer to the residence (especially in the food sector) [

56]. An example is the supermarket chain Mercadona, leader in Spain in the mass consumption sector with 25% of the market share, or the German supermarket chains LIDL and ALDI. Secondly, it has been concentrating around the online channel, with a significant growth in the textile, personal accessories, and household goods sectors [

57]. Both are able to offer lower prices, more product information, and greater variety.

Since 2017, many shopping centers and department stores have had to reform themselves to adapt to the requirements of demand, adapting to a logic of creative destruction [

20]. The reforms have been aimed at offering much more surface area for restaurants and entertainment centers to the detriment of retail space, such as the Glórias (2018) or more recently the Maquinista (2021) [

22]. The department stores of the emblematic Corte Inglés chain have had to restructure rapidly, especially since the unstoppable advance of ecommerce, and especially since Amazon began operating in Spain in September 2011. COVID-19 precipitated the closure of the emblematic shop located in Plaça Francesc Macià in January 2021 [

62]. The crisis of the emblematic Spanish department store brand had been going on for a long time, when, in 2015, they stopped increasing their sales.

Parallel to this generalized process of retail desertification of the city, there is a

jumping scale of the city center due to global tourist consumption. This process translates into fewer shop closures than neighborhoods. Before COVID-19, it was found that the percentage of closed retail establishments in Barcelona’s neighborhoods was much higher than in the city center [

57]. The following section analyzes the changes in the city center based on the in-depth analysis of two retail axes.

On the one hand, it analyzes the Passeig de Gràcia, which is part of the 5-kilometre Shopping Line, defined in 1990, which runs from Plaça Francesc Macià to Plaça Catalunya along part of Avinguda Diagonal, Passeig de Gràcia and Rambla Catalunya, and which forms part of Barcelona’s CBD [

47,

48]. It combines, at the same time, the attraction of metropolitan consumption and that of international and national tourism, which justifies its high hierarchy, while at the same time orienting the real estate market as a whole. On the other hand, Carrer Ferran, the high street of the historic center of the city. The street is very close to the functions of political and administrative centrality. After a long process of disinvestment, it has undergone rehabilitation and gentrification [

63].

3.1. The Adaptation of Commercial Fabric to Global Tourism Demand

According to the Mastercard Global Destination Cities Index 2019, the city of Barcelona is the second city in the world in terms of international tourist spending per resident in the city, with EUR 2793 per inhabitant. According to Barcelona Tourism, 33% of tourist spending was made in retail establishments, which means EUR 64 per day. The remaining EUR 301 per tourist per day (the highest figure in Spain according to the Spanish Statistical Office, “Tourist Expenditure Survey” [

64] was spent on accommodation, transport, food, and mainly entrance fees to monuments. The total expenditure of international tourists visiting Barcelona during May 2016 reached the sum of EUR 1541 million. If we look at the average daily expenditure per tourist, the figure rises to the aforementioned EUR 189 per day [

32].

The daily expenditure per person of tourists in retail activities is logically much higher than of city residents. For this reason, retail activities have increasingly focused more and more on tourists. The process of the modernization of products and services, sales techniques and retail displays has been more visible, especially since the 2008 economic crisis began, from which we have not yet emerged, and which has directly affected the consumption capacity of Barcelona and Spanish citizens in general.

According to an interview with Global Blue, one of the world’s largest shopping tax refund companies based in Switzerland, 34% of the volume of tourist purchases using this tax refund service in Spain takes place in Barcelona’s Shopping Line. According to the same source of information, 46% of spending using this service was by Chinese shoppers, 10% was from the USA and 9% was from Russia. Unlike other cities, such as London or Milan, consumption by shoppers from the Persian Gulf is very low. The weight of tourist consumption in the historic center of Barcelona is even higher than in the Shopping Line, but as it is not luxury or shopping tourism, it is not included in the Global Blue data.

Tourist consumption extends beyond the Shopping Line, throughout the entire historic center, especially the Gothic Quarter. In this neighborhood, Portal de l’Àngel, where many international brands are concentrated, and Portaferrissa, with a less capitalized retail structure, stand out. The axis formed by Carrer Ferran–Jaume I is notable for its specialization in restaurants and, to a lesser extent, clothing. The well-known Ramblas, despite its total specialization in tourist demand, has a more commercial diversified structure.

According to Barcelona Oberta (the association of tourist retail districts), the relative weight of foreigners’ purchases in the most central axes exceeds 30%. In Passeig de Gràcia, was up to 35%; Pelai, Plaça Cataluña, Plaça Universitat, Les Rambles, and Rambla Catalunya was almost 30%; in the Born it was 26%, and in Plaça Real it was 24%. According to Barcelona Oberta, the Chinese and Russians made 97% of their purchases in the Shopping Line, while the rest of the main nationalities were more dispersed and distributed along less central shopping districts. Spending by foreigners occurred mainly in the fashion sector (68.8%), leisure and catering (17.8%), and health (5.8%). Despite the lack of disaggregated data, it is important to note that a very significant part of the fashion spending by tourists was made on Passeig de Gràcia and its surroundings, where the luxury retail is located.

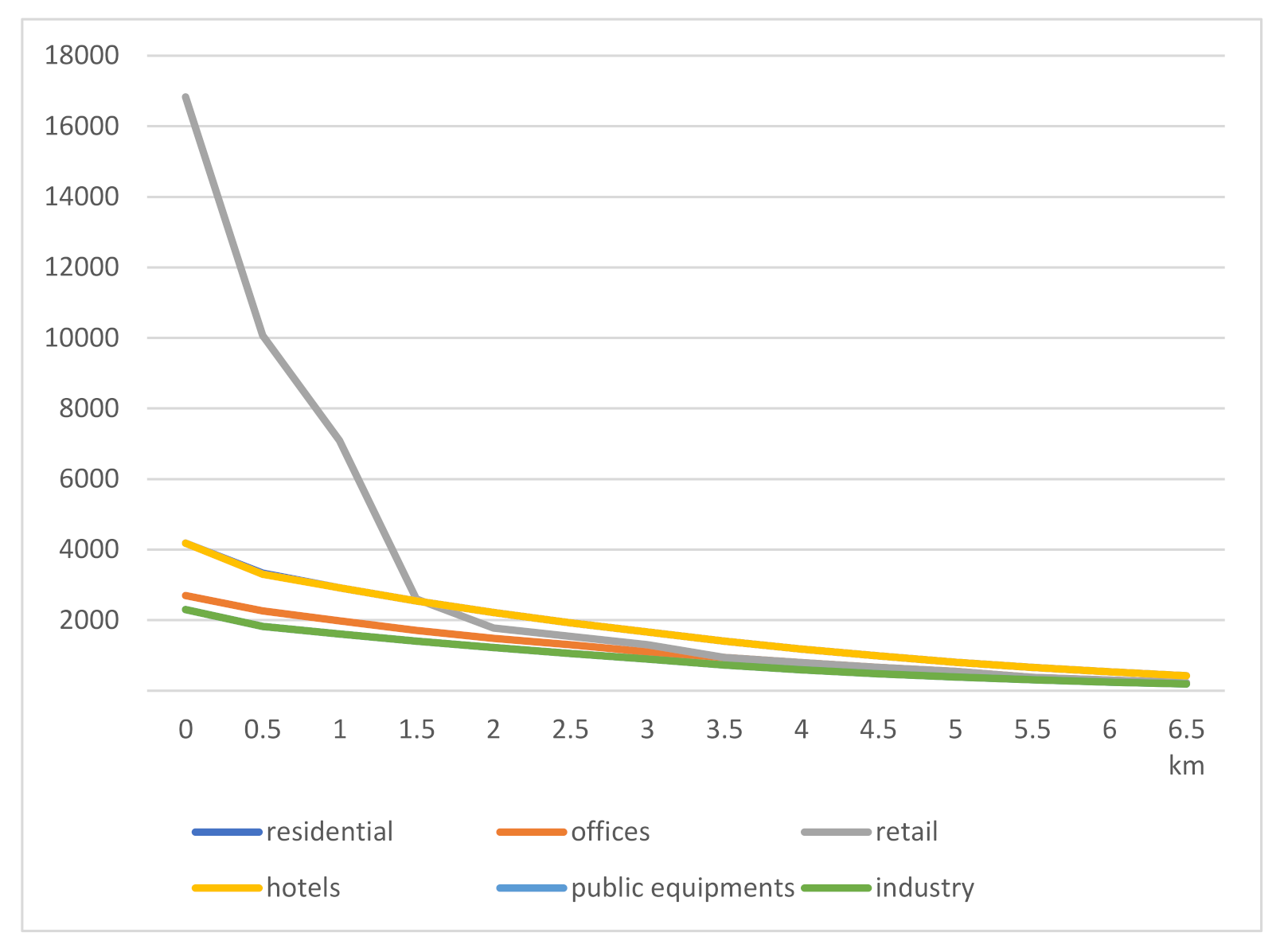

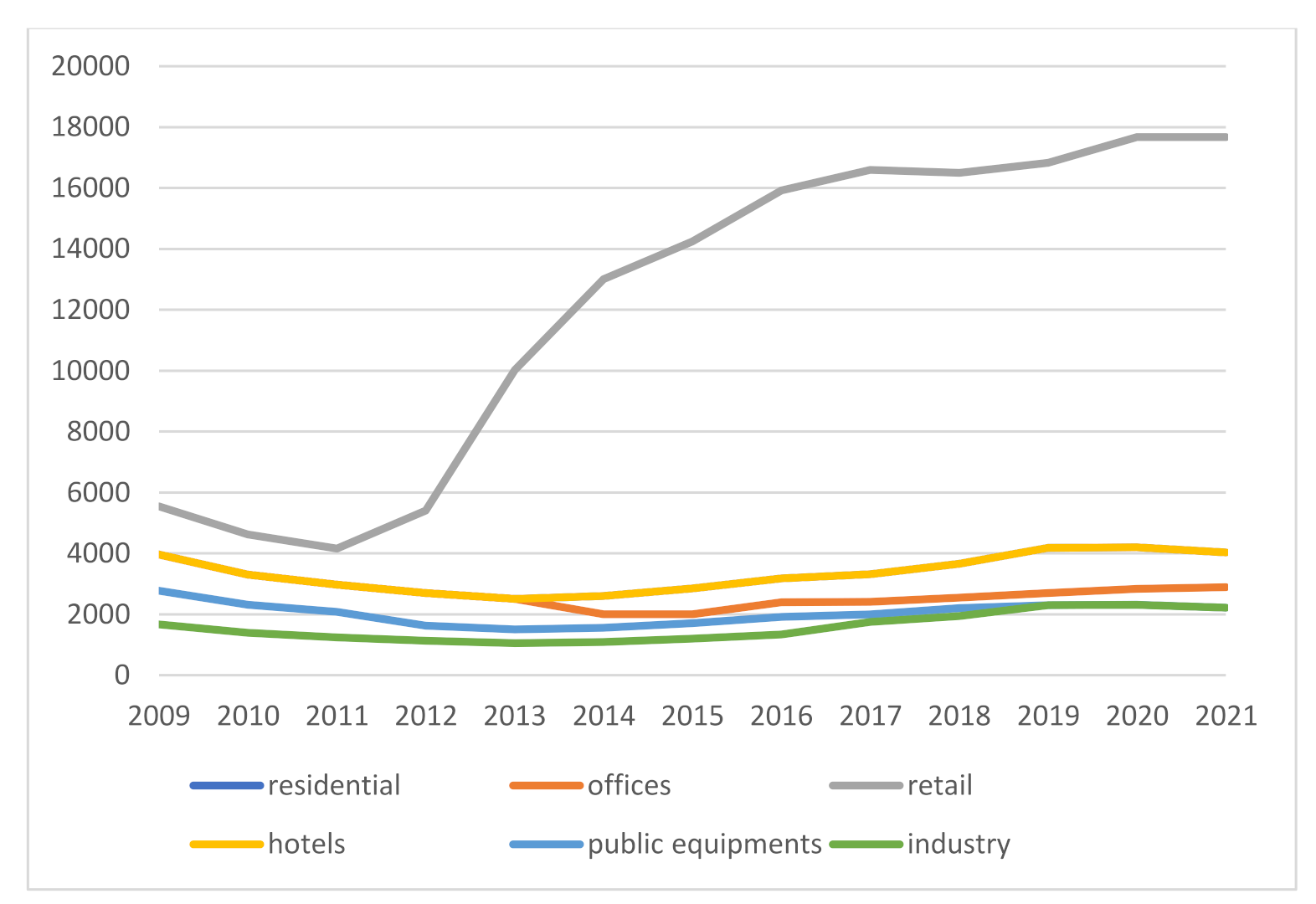

The increase in the number of tourists in Barcelona (from 5.5 million in 2011 to 12 million in 2019) has meant a jumping scale of the CBD and historic center. The increase of global pedestrians in these areas has had an impact on the increase in the price of land for commercial use. During the 2011–2020 period, the value of land for retail use increased by 425% in the center of Barcelona. This positive evolution is not observed for any other urban function (residential, hotel, offices, mainly), all of them without significant variations in land prices

Figure 3. A relative evolution of the city center that cannot be identified in any other city in Catalonia, all of them with a negative evolution in the price of land for retail uses in the city center, and the rapid decrease as we move to the neighborhoods also indicates the jumping scale of the center and the growing retail desertification of other areas

Figure 4.

As a result of this jumping scale, important changes have taken place in retail and services spaces. Firstly, there have been processes of retail gentrification, especially in municipal markets such as Santa Caterina and La Boqueria, which have progressively adapted to international tourism [

55]. Secondly, the internationalization of the street. One of the causes was the finalization of the old rental contracts, which meant that prices were updated to free market conditions. At that time, a multitude of shops that were considered emblematic were bought and/or occupied by international brands [

32].

The Passeig de Gràcia became occupied by residential and retail activities of high prestige, just after the urban gardens between Gràcia and Barcelona were urbanized. It was the place of residence for Barcelona’s bourgeoisie, who were leaving the historic center or returning from the Americas. Many shops that had previously been located on the traditional axis, in Carrer Ferran, also opened. In fact, with the displacement of centrality that the development of Pla Cerda meant, from the end of the 19th century, many of the exclusive shops that were on the Ramblas and in Carrer Ferran and Jaume I migrated to Passeig de Gràcia.

The articulation of a space similar to Barcelona’s CBD took place from the mid-20th century onwards, with the process of bankarization of the ground floor of the buildings. From the end of the 1980s onwards, Passeig de Gràcia became unbanked. Despite the growing financial restructuring, the banks moved to Avinguda Diagonal, an extension of the Shopping Line and closer to the residential areas with the highest purchasing power in Barcelona (Sarrià-Sant Gervasi District). According to data from Perfil de Ciutat [

59], in mid-2019, on Passeig de Gràcia, there were only eight retail premises occupied by the financial sector out of a total of 176.

The de-bankarization was accompanied by the almost massive occupation of ground floors by retail, leaving only 11% of retail premises unoccupied in 2019, many of them undergoing refurbishment and with new tenants already in place [

59]. In the northernmost sector, luxury brands of clothing and accessories for people (Versache, Cristian Dior, Loww, Tifanis, or Rolex, for example), as well as the historic Catalan brand, Santa Eulalia, for example, has been located. In the sector closest to Plaça Catalunya, more mass-market international clothing brands (H&M, Mango, Zara, Pull&Bear), and, more recently, flagship mobile phone shops such as Appel and Orange (

Figure 5).

Carrer Ferran opened in the middle of the historic center of Barcelona and was designed during the liberal triennium (1820–1823) and inaugurated three years later (1826). Its initial intention was to join the Rambla with the fortress of the Citadel. Since its inauguration, the street was occupied by luxury stores and jewelers. The richest people went to live there, becoming the busiest and most prestigious street in the city. Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, many retail establishments were reformed in the modernist style of the time. The street lost its dynamism in the second half of the 20th century. The traditional urban functions of the neighborhood continued to give it a certain centrality, heritage value, and tourist interest. It was in this context that in 1973 the Barnacentre retail association was created, grouping together 18 streets in the Gothic Quarter, including Carrer Ferran. The association’s objective was to fight for the interests of the retailers in the face of the latest changes in the sector that had positioned Passeig de Gràcia as the most strategic district of the city.

With the Olympic reform (1986–1992) and the adaptation of the urban economy to the tourist demand, especially accelerated since the crisis of 2008–2011, the specialization towards this type of demand has been total. In this sense, during the fieldwork carried out in October 2014, it was verified why there were no retail places closed. Three years later, in November 2017, I used the semantic differential technique [

66], and verified how 56% of the 98 establishments were aimed at a tourist demand (souvenirs, hospitality, fast food, official stores of global brands), 33% directly with hospitality, and 45% offered values considered as cosmopolitan.

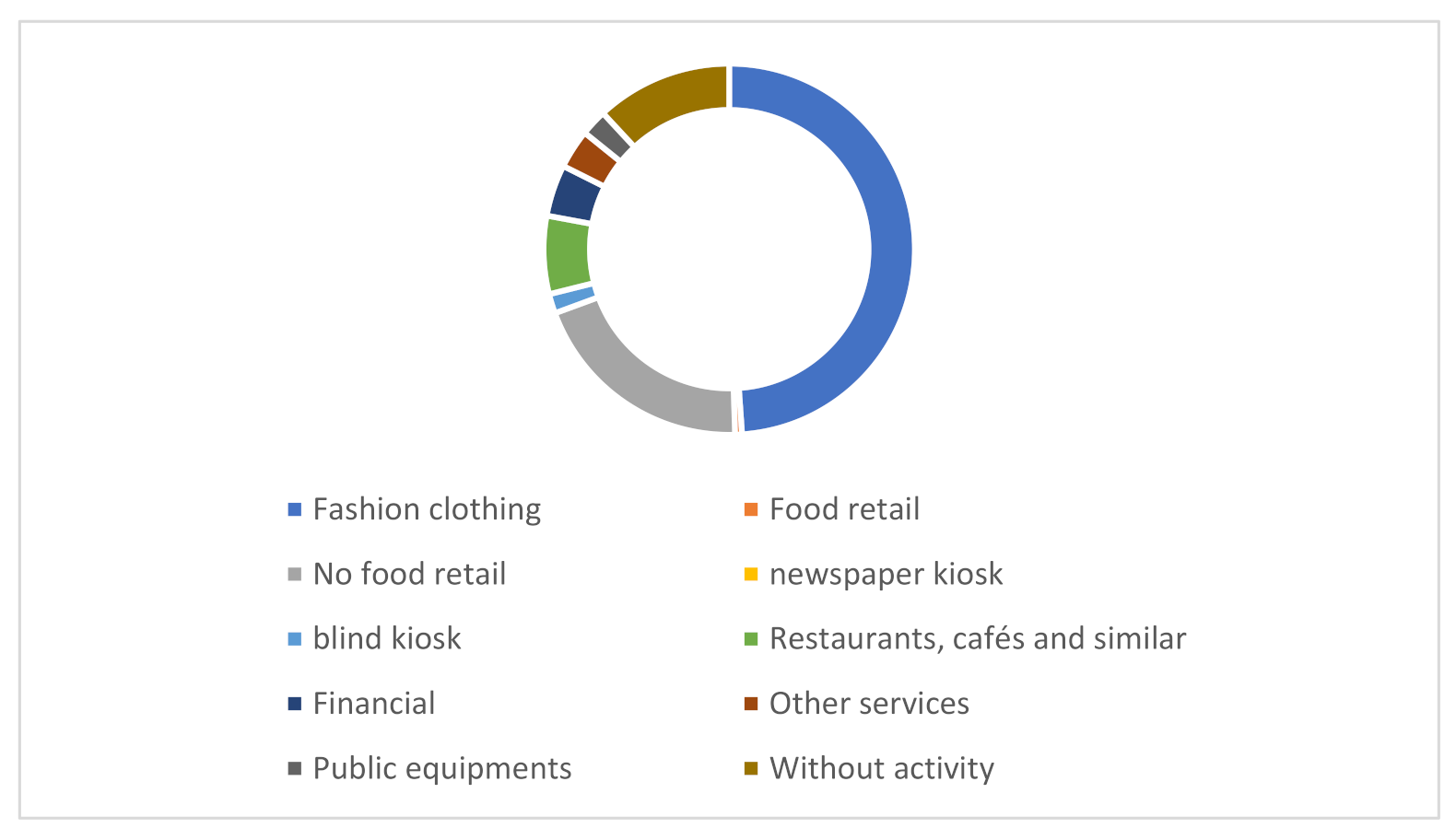

3.2. The Commercial Fabric during CODIV19

Retail desertification has been evident throughout Barcelona, both in the neighborhoods and in the tourist center and shopping centers. It is estimated that the pandemic will mean the definitive closure of between 3000 and 6000 retail establishments throughout Barcelona, according to Barcelona Comerç (the main association of the neighborhood commercial axis), about 15–20% of the associates. This process is occurring despite the fact that the pandemic has to some extent favored neighborhood retail, especially the food sector, thanks to limited mobility and work/study from home [

67].

According to interviews with the Municipal Markets of Barcelona, these shopping places have increased sales during the pandemic. They have captured part of the income that, before the pandemic, went to restauration. They have also been favored by the actions of the public administration. Firstly, they have been classified as basic services and, consequently, are without time restrictions. Secondly, they have received a lot of direct economic aid (creation of joint online marketplaces, adaptation to health criteria) [

68] and indirect aid, persuading consumers to buy from them in the name of saving jobs and forcing shopping centers to close. Not only municipal markets have benefited, but also supermarkets of less than 2500 m

2, which have increased their total retail area during 2020.

The other sectors have not experienced the same positive evolution, even though they are located close to homes. The role of the online channel has been key to understand the negative evolution. Consumers concentrated a lot of their household purchases in the online channel, a sector that increased its sales during the early stages of lockdown. The evolution has been worse for clothing shops, with a very significant decline in terms of demand and a growing concentration on online. In fact, fashion international distribution companies have cut the most jobs in Spain.

The places in the city most affected by the retail crisis have been the shopping centers and the city center. The surface limitations and the total closure of shopping centers implemented by the regional administration have been responsible for the crisis in shopping centers, a fact that has led to a major struggle between owners and tenants of retail premises. On another scale, the total disappearance of tourist demand has precipitated the crisis in the city center. However, the effects of the crisis have been different depending on whether it is a tourist center specializing in leisure and restauration (Carrer Ferran) or luxury retail (Passeig de Gràcia). The following section analyzes these two axes.

During the fieldwork, a total of 174 stores were studied in Passeig de Gràcia, 447 in Las Ramblas, and 87 in Ferran-Jaume I. In Passeig de Gràcia, the proportion of closed stores was 5.2% before the pandemic and 15.5% after [

20], a significant difference (Ꭓ

2 = 8.95, d.f. = 1,

p-value = 0.0027). In La Rambla, the drop in closed stores was from 3.5% to 20.1%, a significant difference too (Ꭓ

2 = 57.03, d.f. = 1,

p-value < 0.0001). In Ferran-Jaume I, the percentage of closed stores decreased from 4.5% to 66.6%, a significant difference too (Ꭓ

2 = 70.39, d.f. = 1,

p-value < 0.0001). To compare the percentage of closed stores among the different retail zones, the number of closed stores after and before the pandemic, relative to the total, was compared. The difference was not significant between Passeig de Gràcia and La Rambla (Ꭓ

2 = 3.35, d.f. = 1,

p-value = 0.0671), but it was highly significant between Passeig de Gràcia and Ferran-Jaume I (Ꭓ

2 = 80.30, d.f. = 1,

p-value < 0.0001), and between La Rambla and Ferran-Jaume I (Ꭓ

2 = 76.41, d.f. = 1,

p-value < 0.0001). In both cases, the pandemic affected significantly less in Passeig de Gràcia. This analysis shows that, even if all areas were affected by the pandemic, the effects were the lowest in Passeig de Gràcia and strongest in Ferran-Jaume I.

3.2.1. The Global Luxury Retail Street in CBD: Passeig de Gràcia

Between 2019 and 2020, the number of international tourists on Passeig de Gràcia had fallen by 98%, but also by 78% of sporadic shoppers and 63% of shoppers who came for reasons of work proximity. In terms of sectors, in Passeig de Gràcia, 90% of closures were in the mass consumer clothing sector (Desigual, Lacoste, Lotusse, Camper and Oysho). There have been no closures among the more exclusive shops, which, despite having seen their turnover plunge, are still there as flag ships (

Figure 6).

3.2.2. The Global Mass Consumption in Gentrified Street: Carrer Ferran

Ferran–Jaume I axis can be considered as the ground zero of post-tourist retail desertification. According to fieldwork in 2017, only 5% of retail premises were identified as closed; in 13 December 2020, the percentage had risen to 67% (

Figure 7). With regard to the typology of closed establishments, it is important to highlight the weight acquired by bars and restaurants (37.3%) and textile and clothing establishments (20.3%) (

Table 3). The closed establishments dedicated to the sale of souvenirs and tourism represented 13.6% each, while the hotel sector represented 11.9%. Take-away allowed many restaurants and bars to stay open during the first months of the pandemic, but they ended up closing after the summer when this sales channel became insufficient. Clothing shops were open until stock was available in the shops. In most cases, renegotiating the rent was impossible and access to loans was not enough to guarantee the viability of the business.

4. Discussion

In this article, we focused on commercial fabric in Barcelona and aimed to show what effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had, above all, on Barcelona’s retail structure. At the empirical level, I have analyzed the different levels of the retail structure, and, in greater depth, the retail spaces in the city center, which are more accessible and symbolic, and more specialized in global tourist demand. Firstly, Passeig de Gràcia, the most internationally prestigious street located in the Eixample district of Barcelona, in the traditional CBD of Barcelona, which has never experienced a process of retail and real estate devaluation. Secondly, Carrer Ferran, the main street of the historic center, which lost its centrality in the mid-20th century once the Passeig de Gràcia was built, and which, after some devaluation, has been subject to urban rehabilitation.

The results show how the effects of COVID-19 on retail fabric have been different depending on the scale at which the demand for these centers is structured. At the local level, home confinement has to some extent favored shopping close to the place of residence, especially for food and home accessories. Nevertheless, the trend of retail closures has continued and even accelerated.

A very important change of trend has been observed in the tourist retail axes of the city center. The number of empty shops has gone from four to fifty-eight in Carrer Ferran, in the gentrified historic center. To a lesser degree, the closure of establishments has also occurred in the CBD’s luxury shopping street, Passeig de Gràcia, with 15% of premises being closed without tenants.

One of the important issues is: when will tourism recover? The perception of the risk of travel [

69] as well as the restrictive measures established by governments on mobility between certain countries will be extended over the next few years. These facts, together with the fragility of the global system, point to an uncertain future scenario. However, it seems clear that tourism demand will hardly ever be as global and massive as it was between 2008–2020. Global tourism mobility post-COVID-19 will be much more selective, both in terms of states and in terms of consumer purchasing power.

5. Conclusions

That supply-side retail activities are embedded in global supply logics has been studied many times. Less studied has been how some retail places are directly dependent on the global mobility of consumers. This aspect has important implications for urban theory: urban centers can be identified that are not structured around a traditional hinterland or periphery, like Barcelona. This aspect links with the thesis of other authors around planetary urbanization, and highlights the importance of multiscale analysis to understand urban complexity. In this sense, the impact of COVID-19 on global consumer flows has meant a downscale for the center of Barcelona. In the absence of an overlapping of central functions at different scales, there has been a total collapse of the centrality of the place. This fact is especially noteworthy in the case of Carrer Ferran. Despite the lockdown, the maintenance of the metropolitan and regional centrality of Passeig de Grácia has somewhat limited its collapse. The relationship between the large global retail operators on this street and the lower percentage of closures should be investigated in the future.

From the point of view of urban planning and management, the susceptibility of territories specialized in global tourist demand has been highlighted. It seems clear that resilience will be achieved if retail areas exercise a multi-scale centrality, and not only globally or for the residents who live there. However, the global logistics of the market, especially the real estate market, drive this functional specialization. Those activities that are more profitable or that attract more consumer income, in this case, global tourists, are attracted to the center. The overall centrality of the center of Barcelona has led to a rise in the price of land for retail use. This has brought the management of retail activities too close to real estate management, making it almost impossible to rent retail premises to meet the needs of residents. The limitations of retail policies to preserve retail heritage were already identified in 2015, when the old rents ended. Their cessation meant a major change in the landscape, as international brands rented or bought these premises.

The unstoppable restructuring of the retail sector as a consequence of the massive diffusion and concentration around the online channel points to an increasing closure of retail activities at a street level. Store closures are also affecting the most capitalized and localized companies, such as the clothing stores of international brands, not only the smaller and less capitalized ones. This process has been going on for about 5 years. COVID-19 has accelerated it abysmally, adding the collapse of retail activities linked to tourism. We can qualify the process as a pandemic retail apocalypse, structural in nature and with no expectation of reversibility.

The main limitation of the study lies in the time scale. It is still difficult to imagine the future in a clear way. There will probably be a slow recovery of tourism in Barcelona that will allow some retail establishments to reopen, but far from returning to pre-pandemic levels. However, the concentration of local consumption around the online channel will continue to deepen, and the closure of street-level retail establishments will continue. As far as spatial constraints are concerned, it would be of vital importance for retail and urban studies to investigate more global tourist cities. This would provide a better understanding of the global demand. It would also provide a better understanding of the effects of COVID-19 on retail activities in cities with different functional structures, business, and historical realities. It would also be important to analyze the effects on the retail structures of urban realities with different centralities where the weight of global tourism is non-existent.