1. Introduction

The booming digitization and virtualization trends, which have gained a momentous thrust during the COVID-19 pandemic, affect all aspects of human life with unprecedented speed and at a global scale. On the one hand, the ‘new normal’ requires not only a complete overhaul, but also a restart, of health systems; more importantly, it also requires a rethinking of human welfare, healthy lifestyles, and reconnection with nature as well as related recreation within open and nature-based tourism. On the other hand, the virtualization of Nature, through its digital representations, is becoming the main, if not the exclusive, information source fir the increasingly urbanized and tech-dependent global consumer.

The conceptualization of nature as ‘heritage’ has its positives and negatives. While the former emphasizes respect and sustainable governance opportunities, the latter includes the idea that humans own Nature and are able, even obligated, to manage, in order to survive and improve their lives. The authors prefer to employ the heritage concept in the context of the necessity to perceive both Nature and Culture as inextricably intertwined parts of an endowment: something so valuable that people receive, are bound to protect, add to, and bequest it to future generations. The meaning of natural heritage is mediated by cultural influences of contact with nature [

1]. Lowenthal [

2] points out that heritage of culture and nature are indivisible, but they evoke different modes of communion. Konsa [

3] points out the need to stress on the uniqueness of heritage management, given the strong relationship between the views, goals, and expectations of the respective communities to the location of the heritage. This link is very significant, due to the high dependency of heritage on its interpretation, valuation, and use by contemporary society in everyday life [

4].

Branding a nature site as world heritage is a powerful nature-based and cultural tourism enhancement. The impact of listing a site on the World Heritage List on the motivation of visitors is a subject of growing debate in the scientific literature [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Although often seen as a panacea, some authors see it rather as a placebo [

13,

14]. Without underestimating the importance of the ‘heritage’ brand, they show that it is not always a sufficient motivation for visits to sites included in the World Heritage List. Despite these findings, no studies have yet been conducted to investigate the reasons for this placebo effect against the background of limited publications on marketing practices on protected areas and natural heritage sites [

15,

16,

17]. At the same time, leading institutions develop targeted marketing and management plans [

18] and use digital marketing strategies and tools to construct the identity, image, and reputation of natural heritage sites.

Bulgaria is an established tourist destination that boasts impressive natural diversity, a result of the transitional geographical position of the territory. It is estimated that about half of the territory of the country has significant recreational potential [

19,

20]. Bulgaria also has a long tradition in nature conservation (since 1931). Its natural heritage occupies an important position at European and global scales. Thirty-three percent of the territory of the country is protected (according to IUCN and CBD categorizations), and three natural sites participate in the World Heritage List of UNESCO: Pirin National Park, Srebarna Biosphere Reserve, and Central Balkan National Park (as part of the Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions in Europe). Five natural sites are included in the UNESCO Tentative List of Natural Heritage: Rusenski Lom Nature Park, Vratsa Karst Nature Reserve, Rocks of Belogradchik, Central Balkan National Park, and Pobiti Kamani Natural Monument [

21]. However, beyond the protected sites included in the National Ecological Network, the country has not yet conducted a comprehensive study to identify the full range of sites with qualities and functions of ‘natural heritage’, and there is no officially adopted list of such sites.

Based on this significant potential, and given the complete utilization of natural recreational resources, the adoption of sustainable development policies and promotion of Bulgarian natural sites has led to higher hopes about ecotourism development in the country since the 1990s. To this day, these expectations remain insufficiently realized. Bulgaria remains unrecognizable as an ecotourism destination on the international tourist market and continues to be promoted mainly as a mass sea-snow destination. As reasons for this failure, Dogramadjieva and Marinov [

22] see limited tourist demand to the Bulgarian natural heritage sites due to lack of sufficient information about them and/or undeveloped tourist products; overwhelming competition of other global-scale nature-based destinations; and the lack of state willingness and political support for the development and promotion of Bulgaria as an ecotourism destination. These conclusions, made a decade ago, today raise the question of what actions have occurred to overcome these gaps and challenges, given the opportunities offered by modern technology. Studies specifically devoted to the presentation of Bulgarian natural heritage sites in the digital environment are lacking.

Provoked by the above, we undertake an analysis of the information provision about the Bulgarian natural heritage in a digital environment, officially managed by the respective organizations/bodies of these sites. The goal of the study is to benchmark the web presentation of Bulgarian natural heritage compared to world-class examples of natural heritage brands. The results aim to contribute to the effective branding of Bulgarian natural heritage and the lasting retention of heritage-based tourism and recreation.

2. Methods

This study adheres to the concept that natural heritage is an ecosystem value, which is simultaneously a source and/or result of the interactions by people with nature. It interprets and uses the term ‘natural heritage sites’ for areas that are particularly favorable for ‘human-nature’ communication through nature-based, in fact, natural heritage-based, tourism and recreation. The investigation results have to define whether: (A) the selected NH sites are ‘present’ in the Internet space with their own, self-managed, i.e., ‘official’ websites; and (B) the internet information about these sites sufficiently and appropriately emphasizes their natural heritage characteristics (

Figure 1).

Commercialization and marketing play a crucial role in maintaining public interest in natural heritage sites and, thus, provide the political and financial capital for their utiliza-tion. The digital type of marketing has rapidly increased its share among the many other relations between natural heritage and tourism and recreation, e.g., bequest, conservation, protection, and investment. Since this relatively new form of marketing takes place in an electronic environment, many authors [

23,

24] also call it e-marketing. Among the multi-tude of opportunities that benefit the tourist industry, NGOs, and unorganized customers, this type of marketing offers comprehensive information, branding, functionality, interac-tivity, visual communication, relevant advertising, public relations, viral distribution of messages, and measurability of outcomes [

23].

Grubor and Jakša [

25] propose the term ‘internet marketing’, as a subset of digital market-ing that particularly uses the Internet for achieving the same goals. Constantinides [

26], on the other hand, suggests the Web-Marketing Mix framework, in which the website of the organization is the cornerstone of any Internet marketing strategy. As an element of criti-cal importance, these websites accomplish a substantial mission, including attracting traf-fic, communicating with target audiences, and branding [

26]. Their content should be a simultaneous expression of both the online identity and the brand of the organization that manages the natural heritage site.

The growing attention to the treasures of NH sites increasingly raises the topic of their identity in the light of the concept of “competitive identity” [

27], where branding plays a significant role. The conceptual model, as developed by Ghodeswar [

28], of a successful brand identity includes four steps: positioning of the brand, communicating its message, delivering the brand performance, and leveraging the brand equity. To increase the effec-tiveness of investment promotion and sustainable business partnerships, the authors propose that e-communication strategies establish the brand identity of a heritage site as a strategic asset that relates, first and foremost, to the local communities.

Google search by keywords enables the identification of the relevant websites (Step 1). According to current trends in digital marketing, particularly in view of search engine optimization (SEO), the search has been reduced to the third Google page. Structural analysis of the main channels for online information of this kind facilitates the assessment of the current state of the online identity of the studied sites from the position of an Internet user.

The study accepts that the UNESCO World Natural Heritage List features the Bulgarian sites of global importance. However, there is no such list of sites of national importance and even less information is available about sites of regional or local significance. On the other hand, many areas and natural elements in the country have official status as sites, encoded in various laws and regulations. There are also areas that lack any official status but enjoy potential or real popularity among tourists and the general public. Therefore, the investigation focuses on 57 NH sites from all of the above categories (

Table 1). Their selection (Step 2) rests on a stratified sampling procedure, which takes into consideration the twin purposes of nature protection and tourism and related development. The core part of these sites are also protected areas and includes all national parks, nature parks, and natural history museums in Bulgaria (

Table 1, Part A). The rest of the selected sites (

Table 1, Part B) serve objectives which are ecological, but at the same time directly contribute to the promotion of other natural heritage values too. This lower stratum of the selection process applies the following set of criteria: type of management and functions, level of environmental protection, significance, type of exposition, diversified product portfolio in natural heritage-based tourism, and scale of tourism and other related development. The extension of the sample includes sites from all tourist regions and is, therefore, quite representative for the territory of the country [

29].

Strategic management studies often apply benchmarking to measure the relation of an object to the best in its class [

38]. Meade [

39] develops the concept even further and defines it as a formal and structured process of searching for practices, which lead to excellent performance, gathering and exchange of information about those practices, adaptation to meet the needs of their own organization, and, finally, implementation. Krishnamoorthy and D’Lima [

40] stress that benchmarking is a basis for successful competitive positioning.

The creation of such a globally competitive benchmarking system (Step 3) includes, first, targeted analysis of world-class websites of natural heritage brands with established image, sustainable popularity, and exemplary marketing content. The targets of the analysis here include: the UNESCO World Natural Heritage List; National Park Foundation website, USA; platforms of national natural heritage programs; and natural history museums, resorts, botanical gardens, and zoos. (

Appendix A,

Table A1).

The creation of a Digital Benchmarking Criteria System involves setting up two subsystems (Step 4). The first defines the benchmarking criteria, which structure the information content of natural heritage sites, while the second organizes the information according to those criteria, which establish the natural heritage resources for tourism and related activities. This research codes the database content, according to the selected criteria, and feeds it into the respective benchmarking subsystems.

2.1. The Natural Heritage Benchmarking Subsystem

Based on the targeted analysis above, this investigation defines the main topics and attributive criteria, which frame and organize the environmental, political, economic, and socio-cultural information content of the natural heritage benchmarking subsystem (

Table 2). Its content features 8 topics with 63 attributive criteria. Established descriptors from the strategic place brand management area [

41] positively influence its creation and upgrading. The criteria basis systematizes up-to-date approaches that are used worldwide in website creation from the perspective of the ‘site as a source of public benefits’. There is a strong focus on information, supported by a variety of technical visualization techniques, which directly affects the first impressions of users. The aim is clear identification of the natural and cultural individuality of the site as well as purposeful identification of its ‘hereditary’ value through its portrayal as an integral part of the way of life, traditions, and culture of the local population.

2.2. The Tourism and Related Activities Benchmarking Subsystem

The criteria set for digital benchmarking and the respective website features of the tourism and the information about related activities covers 7 topics with 38 attributive criteria (

Table 3); this reflects, first, the availability and, second, the detail of presentation of the necessary information. The marketing conceptualization of a tourist product and its components [

42,

43,

44], refracted through the features of natural heritage-based tourism, has theoretically influenced the construction of this subsystem. The seven thematic areas, adopted in the present study, prove to be the most common and adequately represent the basic global trends and practices in this area.

The comparison of the content of the Bulgarian natural heritage websites to those of the best international benchmarks has been conducted in the period of April–May 2020 (Step 5). The selected binary coding scale, which indicates presence (Code 1) or absence (Code 0) of respective information, minimizes the subjectivity of the judgments and further facilitates the ‘comparison to the benchmark’ process. The negative codes show information deficits, gaps, and shortcomings, while the positive codes reveal good practices. The assumption here is that the sum of the positive codes of all topics and attributive criteria equals 100%, which this study accepts as the global benchmark. On this basis, the study calculates the ‘distance’ of each specific surveyed website to the established benchmark. It also performs such calculations and analyses for groups of NH websites of different types.

3. Results

3.1. Targeted Analysis of World-Class Websites of Natural Heritage Brands

The targeted analysis of world-class websites, which feature natural heritage brands, highlights important trends in their presentation. Their synthesis led to development of the Digital Benchmarking Criteria System applied here. Its most impactful elements include: quick facts about the aesthetic and/or qualitative characteristics of the site; purposeful inculcation of ‘heritage’ features; representation of the natural heritage through its relationship with the local people and the established cultural interactions; prioritization of the most attractive types of tourism, recreation, sports, and leisure activities as well as their integration in the site brand; accessible, yet comprehensive, presentation of the tourist services and amenities provided; specific to the respective site, the definition of business niches and potential for synergies; incorporation of provocative state-of-the-art techniques and instruments for a unique first impression about internet users; and creation of a need for real contact with the site. The quality of the Digital Benchmarking Criteria System should be judged by its success to transform the largest possible number of first virtual encounters by potential visitors with the natural heritage site into real and repetitive visits.

3.2. Bulgarian Natural Heritage on the Internet

Internet information on Bulgarian natural heritage sites is predominantly present on websites of a general type, such as Wikipedia, YouTube, and Google Maps, as well as online travel guides. Several other types of websites also disseminate online natural heritage information, such as various state institutions (e.g., ministries or government agencies) and most municipalities. Last, it is not uncommon to find natural heritage information on private web pages, which resemble the official ones but are administered by unauthorized entities or individuals, i.e., ‘grey’ or pseudo-official communication channels. The format and content of the institutional websites usually provide highly specialized, mostly ecological information. Municipal websites, on the other hand, mainly focus on tourist information. ‘Grey’ websites mostly disseminate popular science and tourist information, but pages with environmental content also exist. This investigation shows, however, that, on average, the official websites carry significant weight as an online communication channel through which the public can obtain sufficiently reliable information about natural heritage sites.

Ultimately, only 36 of the surveyed 57 natural heritage sites (about 63%) have official websites. The conclusion is valid about all National Parks, Biosphere Reserves, Arts Parks, almost all Nature Parks, and even some popular sites that lack official status at the time of this investigation (e.g., the ‘Iskar-Panega’Geopark and the ‘Krushuna Falls’ Geotope). At the other end of the spectrum, no site in the Protected Sites category included in the study has an official webpage. Paradoxically, even the Natural History Museum ‘Srebarna’, which is directly related to Srebarna Lake—one of sites on the World Natural Heritage List—does not feature a website. In fact, only two—Ledenika Cave and Belogradchik Rocks—of five sites in the Bulgarian Natural Monuments category have their own websites. The same is true about approximately half of the Natural History Museums, the Visitor and Nature Protection Centers, the Resorts, and the State Hunting Farms from this research sample. Most importantly, for international tourism development, only 55% of the identified official websites (and 35% from the sample) have foreign language versions.

3.3. Natural Heritage Sites and Their Digital Presentation

The summary results show that the information on the official websites of the Bulgarian natural heritage sites contributes relatively little to their branding: the average score of all 63 criteria is about 24% of the global standard (100%) (

Figure 2). The results for the topic ‘General Presentation of NH Sites’ demonstrates that the official websites promote the heritage value of the sites through two main types of thematic information: ‘History’and ‘Biodiversity’ (54% each). However, in the majority of cases, website authors borrow texts directly from documents without adapting the information to serve a wide audience. Only 44% of websites use the ‘Quick Facts’ approach and it rarely demonstrates the ‘prominent’ features of the natural heritage sites. The websites are often devoid of user-provoking facts and lack visual effects techniques. Geodiversity is greatly underestimated (38% of cases): in the majority of cases, it is understood only as the habitats of protected species. The lack of concrete information for ‘site-to-people’ and vice versa are among the most important deficits: such information is present in less than 35% of the Bulgarian websites. Botanical Gardens and Natural Sites—Popular Tourist Destinations (Krushuna Waterfalls) receive the highest summary results in the ‘General presentation of the Natural Heritage Sites’ topic, 67 and 72%, respectively (

Figure 3a). The latter clearly points to the need for the optimization of information strategies for Natural Parks (67%) and National Parks (60%), which should set the standard for natural heritage information contact with society and most closely cooperate with the recreational industries in natural heritage preservation and socialization.

All indicators in the topic ‘Heritage Values’ show a significant information deficit (26% of all sites). Only 7% of the websites use the term ‘Heritage’ in the introduction of their home pages. The results of the attributive criteria ‘How the site is valuable for the local population’ (26%) and ‘How the site is valuable for the world’ (14%) are almost negligible. In 35% of the websites, there is evidence of publicly recognizable cultural heritage sites, but they are presented in separation of, and without any mention of, their close origin from the natural heritage. This undoubtedly deprives Bulgarian natural heritage of prominence and standing in the ‘eyes’ of local business, tourism, and the creative industries, in general. According to this research, the information scarcity directly leads to the low results reported by the criteria ‘Sustained Significance for Generations’ (25% of the global benchmark) of the natural heritage sites. Resorts (55%) and Palace Parks (50%) receive the highest results in the ‘Heritage Values’ topics (

Figure 3b). Deeper analysis leads to the paradoxical conclusion that the website of the ‘Golden Sands’ Resort presents significantly more information (83% of the global standard) about the value of its nature, than the eponymous Nature Park (17%). This example is very indicative of the absence of a national strategy for the promotion of the natural heritage sites, even in cases that are internationally renowned for tourism development. Similarly, the ‘State Hunting Farms’ group of sites are without a positive indication in any criterion, despite the fact that they generally possess quite favorable premises for the presentation of natural heritage.

The results confirm that the cognitive and educational value of the natural heritage sites is clearly recognizable and best interpreted in the offered publicly available information (49% of cases). However, the official Internet presentations of the studied natural heritage sites lack information (

Figure 3c) on environmental change and vulnerability as well as the direct threat of loss of valuable qualities.

Surprisingly low are the results closely related to the ‘Ecosystem Benefits for Society’ topic (26% of the global benchmark). Indicative of the absence of a consumer-oriented national-scale information strategy are also the average results of the criteria ‘Contribution of the Site to the Local Economy’ (26% of the benchmark). The presentation of the significance of the site as cultural services, ‘Inspiration for art or hobby’ and their ‘Contribution to human health and physiological comfort’, are 23 and 17% of the global standard, respectively; this is also among the most neglected. The analysis (

Figure 3d) shows a striking contrast. There are groups of sites, e.g., Palace Parks, without a positive value of any indicator. At the same time, others, such as Biosphere Reserves and individual Nature Parks (e.g., Balgarka Nature Park), score 100%. The latter achievements are primarily due to smart utilization of recent EU funding in projects dealing with ecosystem services.

The attributive criteria of the ‘Site advantages—opportunities and safety concerns’ topic score 22% of the benchmark, with positive indications of the presence of the requested information. Nearly 40% of the websites use general information on thematic itineraries, but only 18% provide guidelines to ‘position’ the visitor (virtual or real, ‘This is the best place/time for…’) in the most suitable locations for observation of the most prominent features of the site. The potential to increase consumer interest through the ‘Communication with other sites of importance’ has been largely ignored (25% of the global standard). Information, related to the protection of the natural heritage sites, including restrictions for their use, is presented in only 25% of the analyzed cases. This is a negligibly low share, despite the direct relation of such information to the safety of visitors. Only four percent of websites provide preliminary information to their visitors to help them prepare their visits, e.g., ‘What do you need to know before visiting the site?’. Among the groups of natural heritage sites, National Parks and Botanical Gardens feature the highest results for ‘Site Advantages-Opportunities and Safety Concerns’, but even their websites cover only 50% of the selected indicators (

Figure 3e).

The data for the ‘Site promotion’ topic show a result of 21% information availability about the criteria applied. In 40% of the cases, the websites display site development information, but in most cases, it is related to site maintenance rather than business initiatives. The presentation of local traditions, produce, and crafts, derived from the natural heritage resources, is identified as the most serious deficit of these websites: only seven percent of them display such information. Similarly, just 35% of the sites participating in the survey use additional venues to connect to users by linking their official websites to social networks. The opportunity to share visitor ‘stories’ (11% of the websites) is seldom used as an approach in site promotion and the stimulation of positive attitudes towards the respective natural resource. Among the different groups of natural heritage sites, Botanical Gardens (50%) and Resorts (43%) show the most favorable overall values (

Figure 3f). The potential of groups of sites such as Hunting Farms, Biosphere Reserves, and Nature Parks remains largely untapped.

The results for the topic ‘Public engagement’ show a poor provision of information (23% of the global standard) about available connections and optional interactions with partner institutions and organizations. Only the traditional connections with the educational system–the main source for supplying information about the public significance of the sites–clearly stand out (42% of the benchmark). However, the results register a low percentage (25%) of interaction with the local public and its involvement with the event calendar of the sites. The information about active voluntary activities is minimal (only 11% of cases). Much-needed information about public support is absent: e.g., only seven percent of websites provide information to the audience about the options to donate. Overall, the Botanical Gardens show good PR abilities (50%,

Figure 3g), followed by Zoos and Nature Parks. Unexpectedly low are the results for groups such as Natural Monuments or Features, Hunting Farms, Biosphere Reserves, Nature Visitor Centers, and even Natural History Museums (5–22%,

Figure 3g).

The results of the application of the topic ‘Techniques and design’ feature a combined result of 28% of the benchmark. Their analysis shows that in 67% of the cases the text information makes up over 60% of the content of the site. Obviously, this is a highly ineffective approach to retain the attention of site users. It minimizes their motivation to consider its structure, topics, and subheadings. The deficit of modern approaches that provide visual attractiveness is evident in the results for ‘visualization’: only 21% of selected websites use videos, a negligible percentage (five percent) offer virtual tours, and no 3D models of key natural phenomena exist on any of the surveyed websites of 57 Bulgarian NH sites. Thematic maps with free access are offered by 28% of websites only. The results in the group of Biosphere Reserves (70%) (

Figure 3h) differ sharply in comparison to the overall assessments of the groups National and Nature Parks, Palace Parks, or Natural Monument, which vary between 18 and 40%.

3.4. Tourism and Recreation Information and Its Presentation

The results of this study of the tourism and recreation information, as well as its presentation on the Bulgarian official websites, outline a worrisome picture. Compared to global trends, the average level is estimated at only 24% of the tourism and recreation information benchmark. The details reveal the main gaps and shortcomings of the Bulgarian official websites (

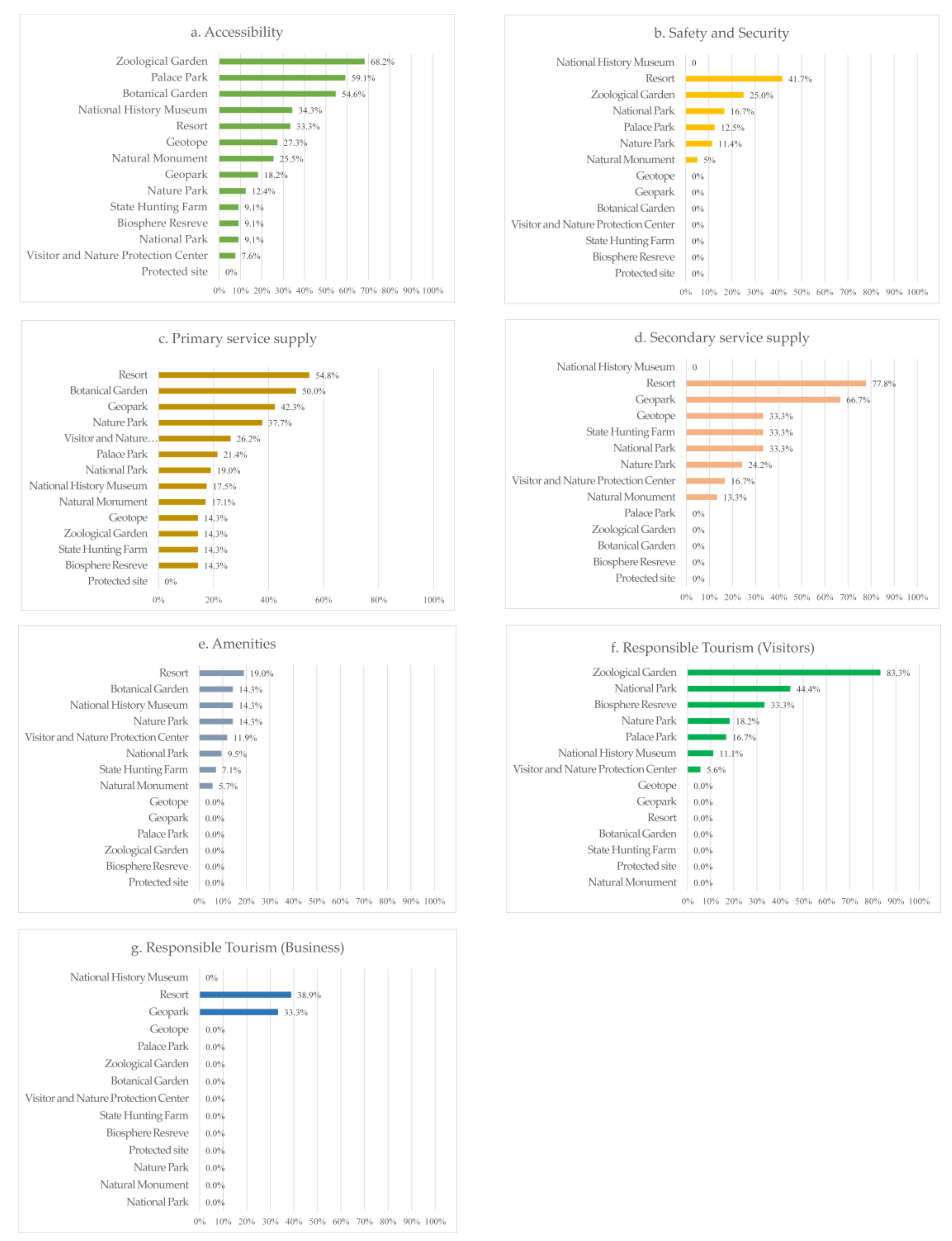

Figure 4).

Given the importance of the issue of accessibility for any tourist destination, the collected data unequivocally shows an unsatisfactory level of information provided. Compared to the reference websites, the average level in Bulgaria reaches a modest 33%. In practice, for about 50% of the websites, there is either no information about spatial-temporal accessibility or it is incomplete. For 68% of the sites, information on their financial accessibility is missing or partially presented. Particularly worrying is the fact that on 79% of the surveyed sites, no information about organizational details for planning visits exists, which clearly shows a lack of customer orientation.

Compared to the other categories of sites included in the sample, the best presentation of their accessibility information is demonstrated by the websites of the Botanical and Zoological Gardens and Palace Parks. The sites from the categories of Natural History Museums, Resorts, Geotopes, and Natural Monuments show a close-to-average level of accessibility information (26–34%). Shockingly, National Parks, Nature Parks, State Hunting Farms, Biosphere Reserves, and Visitor and Nature Protection Centers show an extremely low level (8–12%) of accessibility content (

Figure 5a). Due to the lack of official web pages in the category of protected sites, this kind of official online information is practically impossible to find.

The presentation of the topic ‘Security and Safety’ on the Bulgarian websites reaches a level of only 14% of the benchmark. In terms of the presentation of detailed information, the value for the Bulgarian websites stands at nine percent, in comparison to the global trends. In over 85% of the cases, there are no preliminary instructions for visit organization, safety, and security, including the availability of rescue services and medical care in case of emergency. Except for the websites of Resorts, where the level of presentation of safety and security information reaches about 40% of the benchmark, for the other site categories such information is extremely limited (

Figure 5b).

The websites of the Bulgarian natural heritage sites pay the most attention to the presentation of the primary services as an element of their tourist offers: the average level reaches 38% in comparison to the global standard. For about 60% of the investigated sites, there is no official online information on the primary tourist services provided. The presentation of various thematic categories shows significant differences due to the diverse nature of the sites: the profile of their recreational potential. However, the modest presentation of the performance of the therapeutic and relaxation services (10% of the cases), is worth noting. This suggests that, in general, the health benefits provided by natural heritage seem to be vastly underestimated. For all other primary recreational services, the level of performance compared to global trends is approximately equal: it varies in the range of 40 to 50%. The categories of Resorts, Botanical Gardens, Geoparks, and Nature Parks demonstrate the best performance (38–55%) of the offered services. The other categories of the site have strongly neglected this type of information (

Figure 5c).

The overall level of information provision for secondary tourist services is higher compared to the other topics mentioned in the study. It is, however, still highly insufficient (30% of the benchmark). Content about accommodation and stay dominates the general picture in Bulgaria, but even such information is missing for more than half of the sites. About three-quarters of the sites publish nothing on eating opportunities nor any information regarding the provision of tourist transport services, which falls within the scope of exceptions: the latter is missing in 93% of the selected cases. The provision of information on secondary tourist services generally depends on the level of development of the respective tourist functions: it is most often to be found on the websites of Resorts (78%) and Geoparks (67%). For the other groups, the provision of information on secondary tourist services is a rather unusual practice (

Figure 5d).

The level of presentation of the topic ‘Amenities’ reaches only 15% of the benchmark. This applies to all categories of sites. The maximum level is observed on the websites of the Resorts, but even there it does not exceed 20% (

Figure 5e).

The analyzed data shows that of all the topics considered so far, the one related to the promotion of responsible tourism is the least represented. Compared to world practices, its level of development reaches only 12%. Insofar as such information is published at all, its main audience is private visitors. The content aimed at businesses is less that by more than twice, while the furnished information lacks sufficient detail. Considering the acute shortage of information on the topic, the situation about the lack of content for introducing eco-standards and quality standards is the most serious. The breakdown by types of sites confirms that finding information related to sustainable practices on the Bulgarian natural sites falls within the scope of exceptions: the level of presentation of such content by type of sites generally does not exceed 20% of the global standard. A good example of addressing information to visitors about responsible behavior is demonstrated by the Zoo websites. National Parks and Biosphere Reserves also show some activity in this aspect, while on the websites of the other categories this type of information is either an exception or missing. Information directing business to corporate social responsibility is found only on the websites of Resorts and Geoparks. The latter can be interpreted as an indicator of a lack of collaboration in general between the governing bodies of the natural heritage and tourism and recreation business in Bulgaria (

Figure 5f).

4. Discussion

4.1. Typology of the Bulgarian Natural Heritage and Its Official Presence on the Internet

The typology of the Bulgarian natural heritage sites applied for the purpose of the study allows the following challenges to be identified, which require further research and analysis. The fact that no official list of natural heritage exists in Bulgaria limits the representativeness of the spectrum of sites this study covers, particularly in terms of their diversity and significance and, especially, at the regional and local scales. To overcome the above challenge, this investigation assumes a broader view of natural heritage sites in Bulgaria and interprets them as objects that foster “people-nature” relations through heritage-based tourism, sport, and recreation development. These include the sites of conservation significance, which are traditionally placed in the focus of the topic of heritage, as well as sites of economic importance and those that have acquired hereditary value due to other reasons. All sites are analyzed here as sources of cultural (recreational) ecosystem services, which greatly contribute to the construction of cultural identity and serve as a prerequisite to a number of diverse business initiatives.

The analysis, evaluation, and classification of the NH sites in Bulgaria present another important challenge, which is related to their official and informal public communication, especially online. The presence of the many diverse communication channels that present Bulgarian natural heritage is a positive sign. However, this multi-channel environment allows for the creation of several simultaneous online identities with different, often conflicting, emphasis. The same sites are presented as sites of conservation importance on one channel, as sources of recreational benefits on another, and as tourist destinations on a third website, etc. This produces fragmented perceptions and obscures the true identity and value of the respective site. Multiple presentations prevent the users from acquiring clear, distinct, and objective impressions and are likely to lead to a decline in trust, due to the reliability of the sources of information. An optimal model for the site identity of the Bulgarian natural heritage should provide both information consistency and emphasize its multi-layered nature in the minds of users, e.g., the “onion” model [

45].

On a positive note, more than half of the sites in this study have developed websites. This suggests that authorized bodies support the digital promotion and dissemination of official information about natural heritage. Nevertheless, a significant part of the surveyed sites does not maintain their own websites. The large differences between these groups of sites, and even within the groups themselves, show that promotion and dissemination efforts are not a result of a unified and purposeful e-marketing policy, but rather of individual institutional and interdepartmental initiatives. The investigation found a vague and fragmented management structure as well as a very wide range of stakeholders in Bulgarian natural heritage, which includes several ministries and agencies, a multitude of municipal administrations, NGOs, regional and local associations, and private companies. Undoubtedly, the lack of coordination and a common vision for Bulgarian natural heritage has had a negative impact on the process of disseminating official online information about its sites.

4.2. Presentation of Natural Heritage Sites in a Digital Environment–Strengths and Weaknesses

The results from the data analysis for ‘Information about Natural Heritage and its Presentation’ provide arguments to the conclusion that the official websites of the Bulgarian natural heritage sites suffer from serious information deficits and lack the strategic vision for structuring their brand identities. The websites emphasize the conservation significance of the sites, but generally neglect their functions and values that are important in the daily lives of people. Their contribution to the promotion and appreciation of heritage values is still quite limited and does not include a sufficient basis for building the significant relations between: (A) Natural Heritage and the local population and (B) Natural and Cultural Heritage. Their information content needs the creation of prerequisites for attracting and retaining the attention of active Internet users, especially those who are international and business-oriented, and is ineffective regarding public motivation for natural heritage maintenance and protection.

Despite these generally unfavorable conclusions, there are sites whose Internet-oriented messages show purposeful efforts in building people-oriented and/or business- oriented ‘communicative’ brands: Botanical Gardens, Biosphere Reserves, and part of Nature Parks and Resorts. The significant differences in the results by groups of sites are due to the functional purpose of the sites and the nature of their management and financing. The sites, whose financing depends on their own initiative and close communication with consumers, show significantly better results, e.g., Botanical Gardens and Resorts. Protected areas show a lag in Internet communication, most obviously in the case of Natural Monuments. National Parks show lower-than-expected results, although they have the most significant advantages of using their documented heritage status to develop as a profitable brand. Favorable results have been established for sites whose main functions include sustainable and harmonious interactions with the local population–Biosphere Reserves and Nature Parks. The results give us reason to propose a unified strategy in heritage branding between sites that geographically belong to a common heritage—for example, the Golden Sands Nature Park and the eponymous Resort. The same area is distinguished by a large concentration of individual sites that should be taken into account in the overall strategy: internal Natural Monuments, Geotopes, Protected Sites, etc.

From the point of view of tourism and recreation information, the study shows that the conclusions of Dogramadjieva and Marinov [

22] are still valid today. Despite the efforts made during the last twelve years, the popularization of the Bulgarian natural heritage sites through the use of new technologies is unsatisfactory. The official websites of the Bulgarian natural heritage sites are poorly user-oriented due to the general neglect of necessary tourist information. They are more administrative than marketing-oriented websites. The main substantive shortcomings in the fields of security, safety, and amenities confirm this conclusion. The ‘tourist offer’ of the sites is presented at a basic level through information mainly on accessibility as well as primary and secondary supply services, but even in these areas there are serious gaps. In general, it is difficult to give good examples of sufficient and detailed presentations about tourist and recreation information. However, as expected, the websites of Resorts demonstrate a better level of information performance. It is interesting to note that the websites of natural sites that lack official protected status, according to the current state legislation–Geoparks and Geotopes–in many respects show a better presentation of their tourist offer than those with an official status.

The governors of natural heritage sites should place explicit emphasis on the official status of their respective site, its unique character, and its specific priorities and objectives. The main indicators, which create the ‘natural heritage’ brand, depend on the availability of financing and site management. In Bulgaria, governance often happens under conditions of shared responsibility; most often, involving irresponsibility by more than one state, regional, or local institution. An adequate accent on the purpose of the natural heritage sites and public involvement would alleviate the important gaps in the content and structure of the information offered on the websites. Sites, such as Cultural Landscapes, e.g., the park of the Vrana and Euxinograd Palaces, Biosphere Parks, Nature Parks, Geoparks, and State Hunting Farms, demonstrate very large, but unrealized, potential in this view.

5. Conclusions

This research proves the advantages of contemporary digital marketing techniques in the development of an Internet vision of natural heritage sites and their promotion as tourist destinations. The Digital Benchmarking Criteria System developed and tested in the study is fully applicable to the presentation of sites in diverse geographical environments. The results prove informative, both in the case of an individual site as well as for development of the digital presentation strategies of tourist destinations at the regional and national levels.

Based on a comparative evaluation of the presentation of Bulgarian natural heritage sites, specifically their web branding strategies and practices in respect to world-famous sites, the study shows the main gaps and shortcomings in the case of Bulgaria and provides recommendations for overcoming them. The results show an unsatisfactory level of representation of the heritage value of the Bulgarian natural heritage and a severe depreciation of the provision of the necessary tourism and recreation information, in comparison to the selected global benchmark. It recommends that future studies should try to exhaust all possible aspects of successful brand identity creation, in order to overcome the ‘placebo effect’ of empty ‘heritage’ labelling. Investigation of other formal and informal online communication channels would be especially useful for the study of the online image and reputation of Bulgarian natural heritage. Based on the interpretation of the recreation and tourism industry as an active expression of the awareness of the qualities and functions of natural heritage, as well as the criteria for their recognition by society, this study advocates: First, the urgent creation of official lists of Bulgarian natural heritage sites, differentiated in their significance from the local, national, and global scales and its implementation in the regional development practice. Second, integration of these lists of natural heritage resources in the marketing policy of the tourism and recreation industry at the respective geographic scale, targeted toward the consumers in these markets. The desired outcome of this integration is the sustainable establishment of Bulgarian Natural Heritage as an umbrella brand. Third, the development of an up-to-date strategy for the e-branding of natural heritage sites. Fourth, active communication with the responsible parties about the practical application of such a strategy.