Abstract

This article (visual essay) provides a glimpse of a field trip ventured by design students as part of a larger study of developing a localised version of design education for sustainability, focusing on the wants and needs of non-urban populations in vast Russian hinterlands. The central goal is to introduce would-be designers to the concepts of locally appropriate technology and sustainable/circular living by real-life examples and, eventually, teach them to recognise the sustainable potential of place-based technologies and practices of their making, using and maintaining. The primary data came from the trip to Pozhva, a village in Permskiy Krai, Russia, that gained popularity among DIY activists and users of off-road vehicles in Russia in the early 2000s because of its unique, community-centred manufacture of lightweight ATVs on low-pressure tires, nicknamed “jeeps”. This article presents the students’ journey in a comic strip portraying a composite character of technologies and their user-designers as experts in local conditions and (subconsciously) agents of circularity. The article closes with a discussion on the expedition’s discoveries and learning outcomes, correlating them with broader implications for design education.

1. Introduction

What constitutes the process of teaching and cultivating designers for a sustainable world? Half a century ago, Victor Papanek’s seminal book [1] became a manifesto of the revolution in design and design education—an uprising against self-indulgence in “ideal form”, fashion for “hi-tech”, and unrestrained commercial crass in favour of the environmentally friendly, original material forms in different regions and cultures. His observations and statements are still relevant today, particularly his critique against design education ([2], p. 14). This article examines learning opportunities that emerge when design students are entrusted with a task to (re)consider a global problem through the lens of sustainability. This lens implies scaling down to the local level, where they have to immerse themselves into the community of potential users and approach them as knowledge-keeping experts. While the field study as design pedagogy is not new globally, the details of the setting provide the ground for positioning this case study as an indicative learning example from the part of the “real world”, which is currently underrepresented in both research and teaching. The geographical focus is a Russian roadless hinterland where daily living requires frequent year-round short-distance travelling to meet housekeeping needs, such as hauling hay and other loads, hunting, berry- and mushroom-picking and fishing, with conditions varying from marshy and bumpy terrains to deep snow and black ice.

Having tapered down the scope to the mobility and transport theme, let us outline the Russian specifics of education in the field of industrial design. In theory (i.e., how it is taught in universities), the design process appears to be as follows: the designer engages in the creation of a new thing at a very early stage, acting as an initiator and author of the concept, and collaborating as a peer with engineers. However, in the context of post-Soviet industrial stagnation, this is still a rare case. Today’s Russian industrial and product design is a semi-virtual practice in both education and profession (for a broader analytic overview see [3]). Its final output is an overelaborated 3D model created without reference to real users and manufacturers and, therefore, without any prospects for mass production in most cases. Notably, in the last 5 years, the burning topic of sustainable design has found its way as complicated simulacrum titles into the curricula, without delving into the core of the very concept of sustainability (this is based on one of the authors’ 15 years of experience teaching industrial design at one of the leading design schools in Russia). As a result of this kind of training, graduates often lack connection to the engineering, economic and, more importantly, environmental and human (user) realities of how a product is born and how it exists.

In terms of professional practice, novice designers do not fully understand what a design brief is; in the teaching and learning context it is imposed “from above” while in “real life” it is often compiled hastily with limited resources available, often without contact with or interest in real people (instead, they are abstract “users” or “customers”) and their living environment, with the only objective to sell the final product. Industrial design graduates often have to confine themselves to the role of a “surface decorator” or even find jobs in the advertising of ready-made products which were created by someone else. In other words, Russian industrial designers are not prepared to design in Russia and for Russia.

Why is this so? The main reason is a poor manufacturing infrastructure with very limited potentialities, meaning that the “designer resources” cannot be employed to the fullest. We continue with an example from the segment of transport vehicles in general and in small-scale off-road vehicles in particular. In many regions of Russia, with its unevenly developed road infrastructure all over a vast territory, the demand for cross-country and all-terrain vehicles arises from real-life needs. Currently, this market sector is full of international brands—impressive lightweight off-roaders, mainly oriented towards use in tourism and sports. Given this abundance in the market, a legitimate question arises: why create something of your own if it is easier to select something from the range of ready-made and, at first glance, universal solutions of the international automotive industry? However, in Russia, which is very patchy both geographically and culturally, the needs for lightweight off-road vehicles are very diverse and are not limited to sports and entertainment in natural settings. Thus, design (both for products and processes) should also be diverse, being able to fit in with different environments and user needs. in particular, the existing range of small-size off-roaders for sports and entertainment does not reflect the interests of the country’s rural population—about 37 million people [4]. From the perspective of demand for “special design”, the needs and expectations of these communities have not been studied properly—designers often do not understand how they should approach them.

In fact, rural communities are very mobile and self-sufficient, following the spontaneous principle, “if you’re drowning, you’re on your own”, when virtually everyone has to become “a designer in their own right”. Thus, a whole world emerges in the space of rural road-lessness, that of lightweight off-road vehicles, incredibly diverse in design and technical characteristics. Thus, the “ideal transport” already exists and is operated successfully; moreover, its creation does not need the involvement of professional designers, as the entire production cycle, from concept to making and to disposal occurs without them; it is an instantaneous response to user needs. For instance, a “Buran” snowmobile instantly becomes a donor of the engine for a water pump; waste aircraft wheel tubes turn into all-road low-pressure tires; a chainsaw becomes a boat engine, etc.

This essay and the larger educational project it covers are devoted to the virtually invisible culture of “lay designers” [5], i.e., enthusiastic DIY makers, tinkerers and grassroots innovators in the vast peripheral area of Russia. This heterogeneous community—mostly small town and village residents—make with their own hands what contemporary manufacturing industries cannot produce: they continually develop extremely functional, rational and economical tools and technologies for their real needs in a specific locality.

Often clumsy and offbeat at first glance, these DIY creations hide huge potential: they embody what one actually needs for a life of some convenience and reflect the ‘know-how’ of making it based on the available (usually limited) resources. DIY creations and DIY enthusiasts are manifestations of different, non-urban cultures existing across the vast expanses of Russia, where people rely on themselves and their own efforts in permanent contact with the nature and its potentialities and limitations. If interpreted correctly, these DIY creations present an invaluable resource of solutions, best practices and know-how for professionals whose remit is the creation of things, i.e., designers.

However, it is impossible to understand, appreciate and, first and foremost, use these solutions from out of the depth of the “urban civilization”, with its illusory accessibility of any goods and technologies, bordering on all-permissiveness. There is a gulf between these worlds: while designers have to do a lot of guesswork when searching for design solutions without knowing the actual geographic, cultural and social context in which their product is going to be used, the knowledge the DIY tinkerers possess remains invisible and, thus, untapped.

Intending to close this gap, in this essay we touch upon the first step towards developing a learning tool, a kind of “literacy” course for designers on how to find, analyze and apply this type of knowledge embodied in real technical objects. This is a part of a larger educational development built upon the results of the team’s decade-long exploration of user innovations in the Russian North with its vast low-populated areas, poor infrastructure and remoteness from economic, industrial and cultural centres [6,7,8,9,10]. The course would be unique and novel in that it gives priority to reality over virtuality: the emphasis is made on regional specifics, needs and resources.

The visual essay is centred on an introductory field study (expedition) aimed at would-be designers. The expedition’s fundamental and overall educational approach is the concept of participatory learning rooted in the works by Dewey [11] and Vygotsky [12], and later Brown, Collins and Duguid [13], and Lave and Wenger [14], that encourages learning by doing, situated context, and the involvement of communities of practice. In this vein, knowledge and skills are products of neither a single individual’s mind nor a “from-teacher-to-student” transmission. They are outcomes of a participatory framework that includes both human and non-human actors and renders objects and practices visible through the dynamic adaptation to changing circumstances.

The research quest that we pursued as design educators seeks to encourage students to understand and appreciate the sustainable potential of rural-originated technologies and related making, using and maintaining practices: how do we discover, evaluate and apply this potential in the Russian context? As well as this, what is the role of field studies in this process?

For our research and teaching purposes, we narrowed down the broad concept of sustainability and a sustainable way of living to its practical—circular—implementation, and consider one of its vital components, i.e., re-manufacturing, which helps harness the environmental, economic, and social benefits by extending their useful lives rather than being landfilled or recycled, and, thus, recapturing their added value [15,16]. In our work, the concept of circularity is the core, since it bridges the rather vague and ambiguous concepts of sustainability and a sustainable way of living with the real-life context. The importance of circularity lies in the value created and delivered without actually using or extracting a new portion of natural resources to produce new material objects. By the example of the sector of homemade off-road vehicles, students are expected to obtain practical knowledge on what constitutes reliable, economical, valuable and, overall, sustainable objects for daily life, with attention to the locality for which they are made and the specifics of use.

The main body of data comes from the trip to Pozhva, a village in Permskiy Krai, Russia, that gained popularity among DIY activists and users of off-road vehicles in Russia in the early 2000s because of its unique community-centred manufacture of lightweight ATVs on low-pressure tires nicknamed “jeeps”. The essay presents the students’ journey in a comic strip portraying the composite character of technologies and their user-designers as experts in local conditions and (subconsciously) agents of circularity.

The next section describes how the research was conducted within the chosen community. The main part consists of three narratives (lessons)—on geography, economy and ethics. These topics accidentally emerged in almost every conversation in the field, pointing out implicit aspects of a relationship with technology. Thus, it was natural to distil them during the data analysis. The final part summarizes educational implications and lessons learned. The essay closes by discussing the contribution of the expedition’s discoveries to the understanding of environmentally, socially, and economically adequate practices emerging from within, instead of “imposed” sustainable behaviour.

2. Materials and Methods

We have deliberately chosen the format of a visual essay as it allows us to bridge together fieldwork and observational sketching for the eventual presentation of the investigation’s findings ([17], p. 115). We gathered the inspiration from Escobar’s proposition to rethink ethnography as a design process based on certain trends in design practice and education, such as collaboration, diverse partnerships and outcome orientation ([18], p. 56).

The visual representation is based primarily on data from semi-structured interviews, participant observation and further discussions with peers and participants, adding new insights and dimensions to our understanding. The depicted expedition (9 days in July 2019) was preceded by an early exploration and probing with local dwellers and makers in Pozhva village (3 days in March 2018). During this first encounter, our “gatekeeper” was the local librarian Irina, the wife of a former mill worker and jeep-maker Ivan (pseudonyms applied). We found her via the webpage about Pozhva that she administrated. Thanks to her, we quickly found and approached all our informants—local makers and their families (n = 14). The demographic profile of the informants predominantly consisted of males aged 45–60. The youngest was 20, and the oldest was 65. Also, there were three females: one of them was an active maker and racer (aged 36); the others were makers’ wives (aged 50 and 55). Altogether, we conducted 18 interviews (each typically took 30 to 120 min, either taped and transcribed or using handwritten notes). We complemented the observational ethnography by exploring various archival data, such as personal photo archives of our informants and publications in local newspapers. We also tapped into publicly available personal information on the Internet, e.g., online profiles in social networks and DIY Internet forums. The line of questioning stemmed from the core research interest in the phenomenon of collective DIY activity in rural areas. The topics included the local history of the phenomenon, local names and modifications, structural variations, the design and manufacturing process, the geography of use and the makers’ motivation. In most cases, the locals responded with lively interest and enthusiasm and willingly shared stories from their lives, where DIY transport vehicles sometimes acted as living “characters”.

Author One is a professional illustrator, and it was her initiative to utilize her drawing skills: first, as a means for ensuring a ‘less invasive’ contact with informants ([17], p. 125); and, second, for deepening the informants’ involvement and data analysis ([19], p. 76). She deliberately included herself and other members of the field team (Figure 1) in the pictures to emphasize the educational immersion into the research context and, at the same time, the irreducible distance between the observers and the observed.

Figure 1.

Field team.

During field contacts and interactions, Author One adopted a three-step approach to visual documentation: first, freehand drawing in-situ for ‘ice-breaking’, then capturing people, objects and situations with a camera and finally processing (and thinking about) the obtained visual material with digital tools. in particular, at the last stage, she used freehand drawing upon the photographs and analogue sketches using ProCreate software, reflectively, i.e., focusing on some traits and details and blurring or omitting the others. It is worth admitting that, in some cases, she reconstructed situations that happened beyond the camera’s eye or even could happen only potentially, based on the acquired understanding of people and their technology. In these instances, Author One constructed her drawings as collages enriched with visual data on characters and objects collected in the same location, though not necessarily at the same time. For the final version of the essay, there were five key characters selected (Figure 2), supplemented with verbatim and paraphrased quotations from field interviews.

Figure 2.

Pozhva residents who participated in the research (pseudonyms applied).

The ways in which objects of technology that are grounded in solid infrastructures of resources (materials), tools and professional knowledge, and within certain geographical settings, can generate and establish practices have been widely examined by STS scholars [20,21,22]. Alternatively, there is a body of user innovation and grassroots studies [23,24,25] which have considered user interventions into established manufacturing technologies and practices resulting in new ways of making, using and maintaining the surrounding materiality.

Based on the theoretical insights from both tracks, this essay expounds our observations of technologies and practices in illustrations examined through the lens of “proximal design” [7], highlighting not only the users’ ability to adjust, repair and redesign their machines, but also their knack for creating entirely new kinds of technology and, eventually, coming up with enduring design principles without access to systematically arranged infrastructures or the participation of professionals. Design, here, is a liberating and empowering practice focused on figuring the alternatives for multiple ways of world-making [18,26,27].

The section below introduces three narratives unfolding the contemporary craft of making ATVs on low-pressure tires in Pozhva.

3. Results

3.1. Geography

Globalization has resulted in a dominant culture of mass-production and, increasingly, fully automated manufacturing that can be understood as a place-less, consumption-based economic system ([28], cited in ([29], p. 185), our emphasis). In contrast, traditional making practices are localized and place-specific, maintaining sociocultural, spiritual, functional, aesthetic and/or economic values [29,30]. In rural areas—distant from administrative centres, large industries and infrastructures—geography becomes the primary identifier of a human-made object: knowing the place of origin and use of the object under study allows us to retrace what kinds of need the environment generated and what materials it provided to meet them.

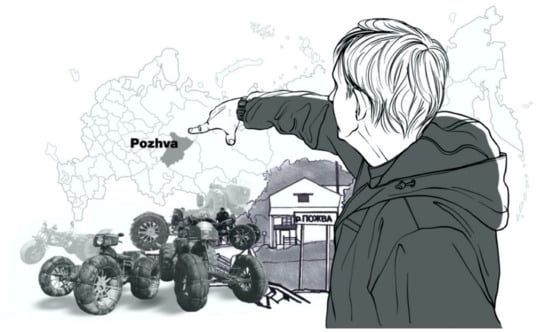

Pozhva is a rural settlement in Permskiy Krai, in the European North of Russia (Figure 3), with a population of 3131 (Census 2010). Its official history began in 1754, when the Pozhva Machine-Building Mill was founded by one of the counts Stroganov. Historians call the Pozhva mill “the cradle of domestic steam shipbuilding” and “the centre of advanced technical thought” in Russia in the early 19th century (materials from the Pozhva Museum of Local Lore). In the days of the Soviet Union, the mill manufactured boats, fire engines, cranes and timber technologies and related components. In the post-Soviet period, the mill experienced financial problems, and in 2014, it was announced bankrupt and closed. In the early 2000s, Pozhva gained popularity among DIY activists and users of off-road vehicles because of its unique community-centred manufacture of lightweight ATVs on low-pressure tires, informally called “jeeps”. In our study, we consider the practice of making ATVs on low-pressure tires in Pozhva as a clearly place-based handicraft with the following attributes: both outer shape and internal structure have evolved to better fit the environment of use; it is widely adopted in the community (there are about 200 vehicles of this kind surviving in the village to date, with a peak of over 500 ‘jeeps’ in the early 2000s); and it is based on a learning-by-doing way of transmitting practical knowledge, with no drawings or written guidelines.

Figure 3.

Geographical context of the study.

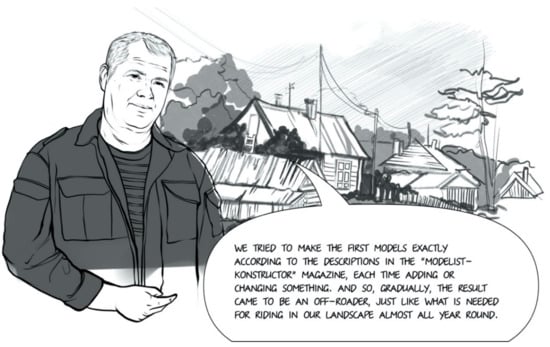

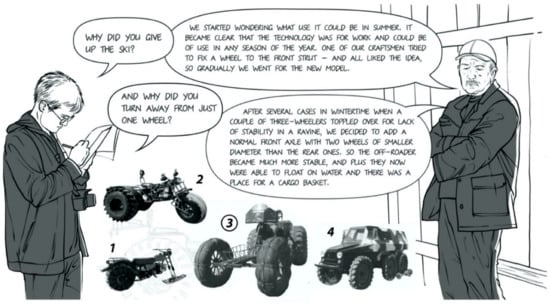

The most eloquent manifestation of the geography is the specific “Pozhva frame”. It has undergone several clearly consecutive stages of evolution (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

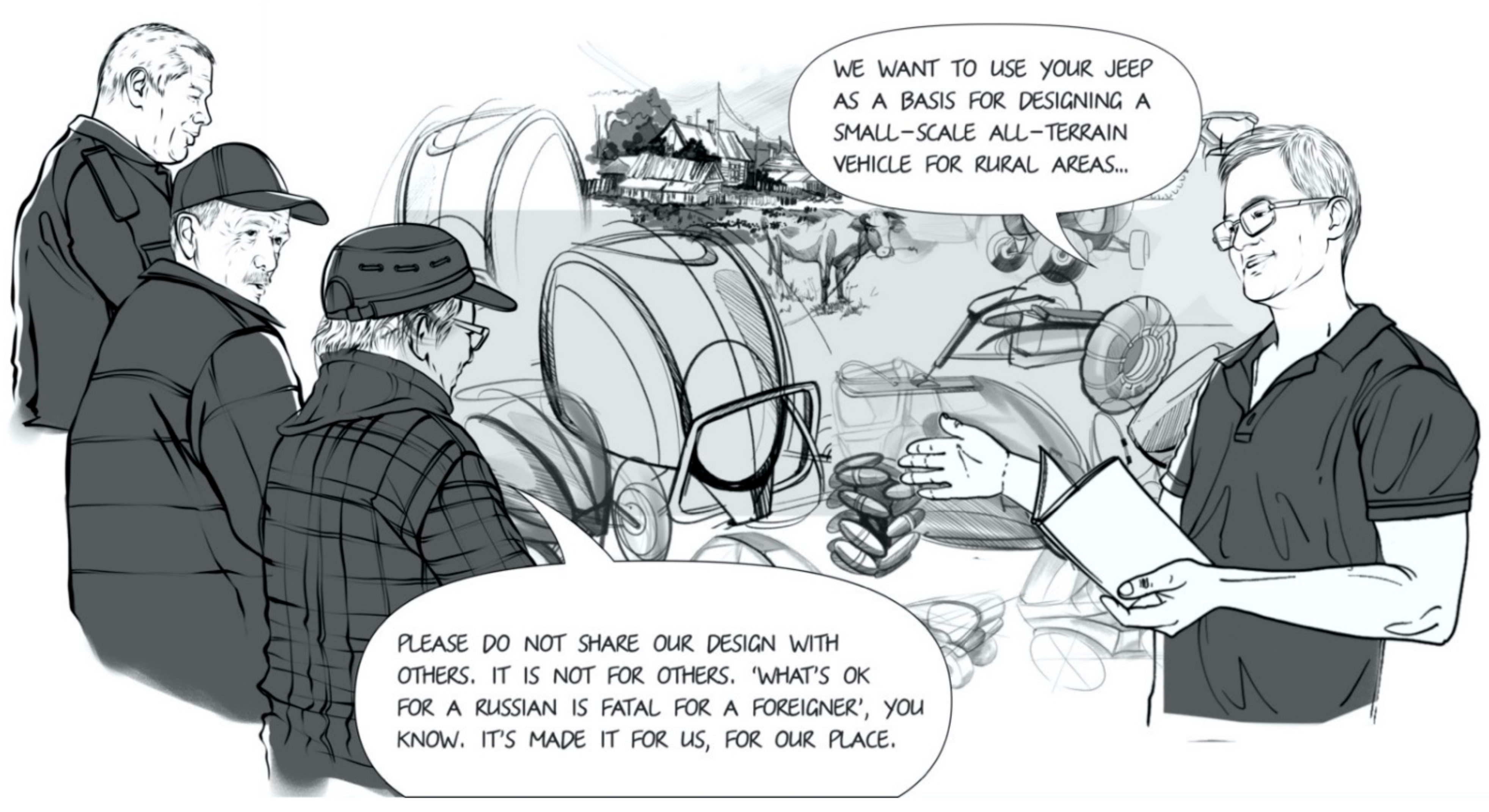

Figure 4.

Describing the origin of Pozhva design.

Figure 5.

Stages of the evolution of Pozhva jeeps: (1) an early version with a front ski was made based on drawings in a Soviet DIY magazine; (2) a three-wheeler was an all-season modification, later advanced to; (3) a four-wheeler that became a “golden standard”; and (4) a six-wheeler, which was a trial that did not fit the requirements of Pozhva’s everyday living.

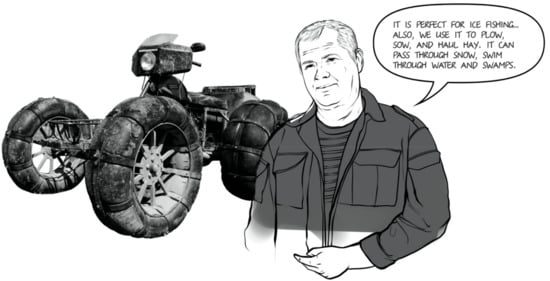

The “pinnacle of creation” is the all-weather use, easy-to-handle and light four-wheeled machine (rear-wheel drive), with a motorcycle engine, an automobile chassis, a luggage box at the rear and a cargo platform in front (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A typical Pozhva jeep and its range of use.

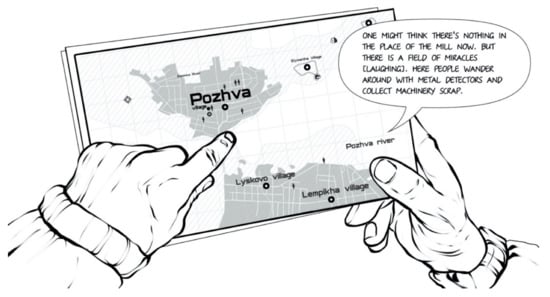

The geographical narrative also covers the sources of parts and materials. The place-based making of transport vehicles inevitably involves external components, but in this case, most of them are, in fact, already localised through reusing and recycling: widely available, mass-produced parts and construction materials come from the artificial environment of backyards, metal stores and the landfills of the local kolkhoz (collective farm), which is full of broken tractors and other machines (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The map of Pozhva and vicinities.

3.2. Economy

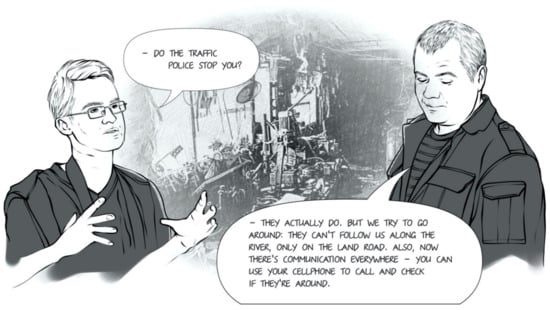

The inventive potential of rural and peripheral areas has been considered by anthropologists and sociologists within a complex phenomenon of “hinterland/remoteness” [31,32,33,34]. Our preceding observations of the development and use of DIY all-terrain vehicles highlighted the creativity of technology users and makers fostered by constantly dealing with the severe environment (roadless and sparsely populated areas with large distances between settlements, harsh climate, etc.) [6,8]. The concrete expressions of this creativity—from sourcing the parts and equipment to using the finished vehicles—often verge upon informal shadow practices of peculiar Soviet “kleptocracy” ([35], p. 253), [36], when company automobile drivers ‘peddled’ the gasoline apportioned to them, plumbers took away tools and instruments, cooks stole fresh meat and deficit food stuffs, etc. ([37], p. 5). Furthermore, in today’s Russia, homemade vehicles are illegal by nature: they are not specified in the Traffic Code, and therefore it is impossible to register them in the State Traffic Safety Inspectorate (Figure 8). In this study, we are not delving deeply into this phenomenon, but find it important to consider it as a backbone for informal economic activities in the “real world”. In the Pozhva case, we observed how these traits have contributed to the overall autonomy—both physical and symbolic—of such “communities of practice” and eventually have led to alternative or informal organization of economic activities. Also, in terms of sustainability, this is a form of utilizing industrial junk that nobody needs any longer (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

About encounters with the traffic police.

Figure 9.

On the tools and machinery equipment for jeep making.

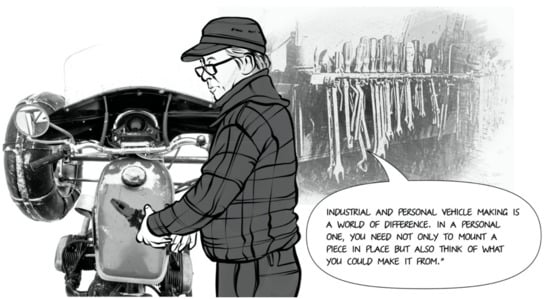

Today, each jeep is an exclusively produced, manual assembly of uniquely sourced (mainly Soviet-produced) components, combined with unique and individual engineering and design solutions. A small share of the parts that required turning, milling and welding operations (e.g., drive sprockets, frames) used to be made in the mill workshops, while general assembling, tuning and alteration are still conducted in personal home garages (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

On the difference between industrial and home manufacturing.

As a new stage of developing and sustaining the craft, Pozhva makers aim to shift towards the current used-parts market completely and, therefore, increase vehicle repairability (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

On the future of homemade vehicles and manufacturing process.

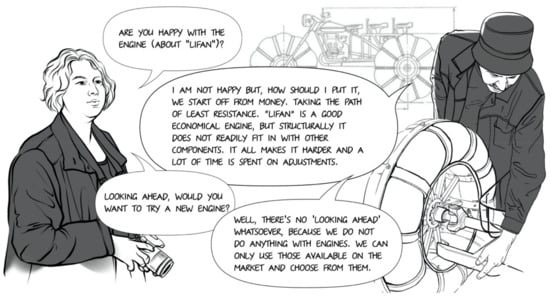

The fluid market of used components forces makers to correspondingly modify their designs to reach adequate (although not optimal) solutions [10] (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

On the compatibility of engines.

The limited availability and everchanging choice of used components also reinforce the meaning of community—the network of friends, workmates and acquaintances in local proximity to reciprocally pull in their resources (parts, materials, tools, competencies, etc.) and, at the same time, to ensure the space for working on their own. For instance, people may group together for the ordering and delivery of the discontinued model of the “Izh” motorcycle from another region (about 300 km away) to get spare parts for their own designs; or, those who possess something from the complex manufacturing equipment of the mill provide access on an exchange (non-cash) basis; etc. Such examples indicate the appreciation of personal autonomy at every stage of making and maintaining and provide evidence for community’s support available at hand at every stage.

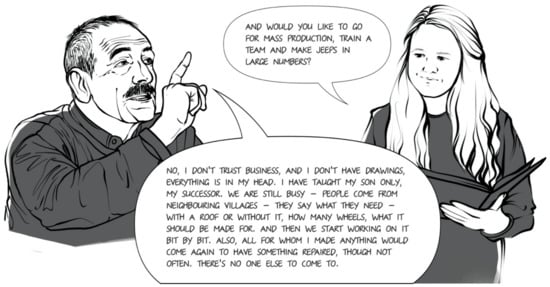

There is yet another side of the informal economics of Pozhva jeeps that reveals itself in the scalability of making activities: none of the makers are eager to grow up into a small enterprise, even those who are commissioned to make vehicles. The main reasons for this are non-formalised and non-transmittable knowledge (no drawings and written guidelines), unpredictable sets of components (no way to make a batch of identical vehicles) and overall distrust of the state–business relationship (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

On the future of the jeep making: knowledge transfer.

Figure 14.

On the future of the jeep making: human resources.

3.3. Ethics

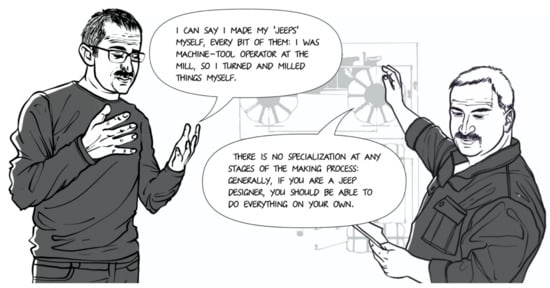

The process of inhabiting and valourising the space by the observed community of practice is based on a specific combination of do-it-yourself culture with moral principles of preservation and the longstanding use of human possessions. Golubev and Smolyak, in their analysis of Soviet DIY discourses, suggest this combination is actually rooted in the domestic cultural milieu ([38], p. 30). The attitude of being frugal and the use and reuse of what is available in proximity [7,39,40] brings forward the particular value of skills regarding what the user can utilise from what is provided by the environment. Most of these skills became available thanks to the Soviet system of mass secondary and vocational training, which enhanced the rates of technological literacy, promoted rich manual workmanship and literally shaped a community of peasants who could dismantle almost anything and, from this pile of parts, assemble a perfectly tailored “self-propelled wagon” (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

On the specialization in the making process.

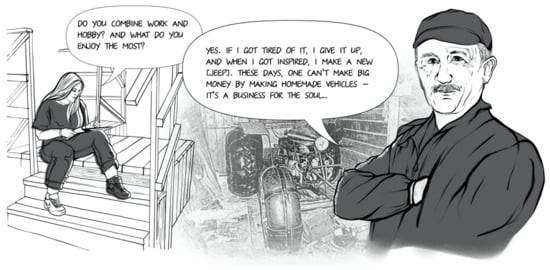

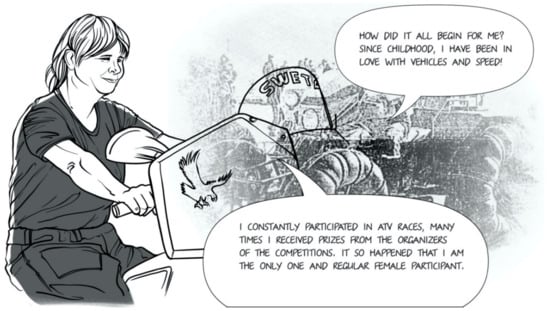

Proceeding next to the practical value of and attitude to being skillful, both making and riding are strongly associated with a feeling of pleasure (Figure 16 and Figure 17).

Figure 16.

On the pleasure of jeep making.

Figure 17.

On the pleasure of riding a jeep.

Some ethical principles and attitudes are obviously not expressed explicitly, so we had to observe and follow people interacting with their vehicles to see them come out. We discovered a significant sense of control over technology (Figure 18) and the time-space on the local scale, sometimes expressed through risky behaviours (Figure 19 and Figure 20). In these instances, handmade vehicles are a manageable means to embody, verify and extend practical knowledge of the locality.

Figure 18.

On maintenance and repair.

Figure 19.

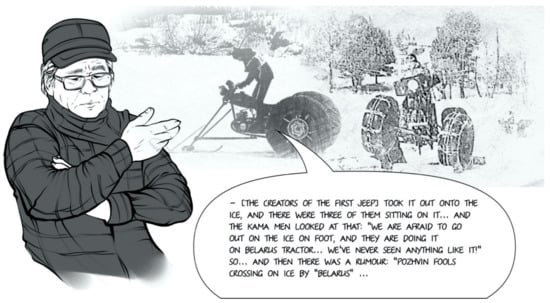

On the risks of use—A.

Figure 20.

On the risks of use—B.

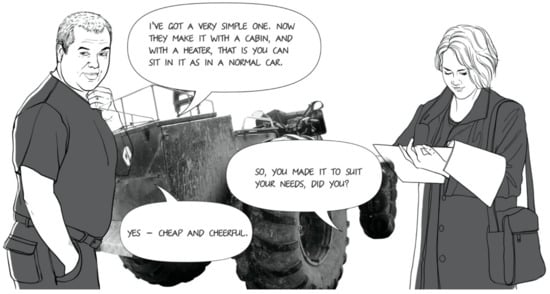

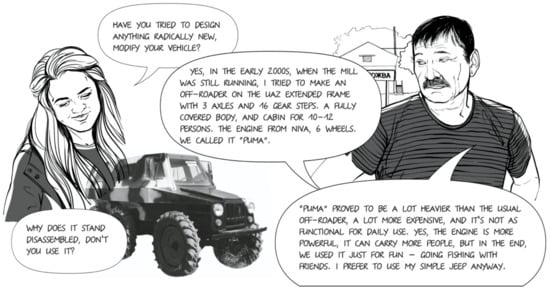

Among others, we discovered “practical aesthetics” [41], i.e., the pleasure and beauty of material austerity and rationality (Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23).

Figure 21.

On the austerity and rationality of the design—A.

Figure 22.

On the austerity and rationality of the design—B.

Figure 23.

On attempts to make larger ATVs.

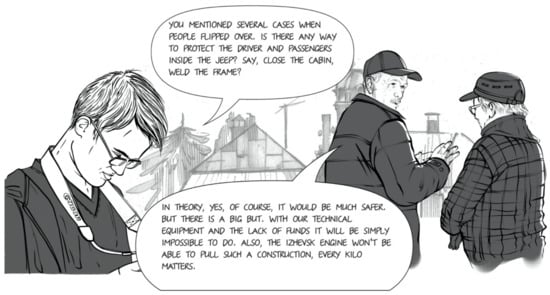

We observed further manifestations of practical aesthetics through co-designing and co-thinking sessions that eventually provoked a critical shift in the students’ understanding of “good (machine) design” (Figure 24 and Figure 25). In discussing “placeless” designerly improvements for Pozhva jeeps, makers insisted on the adequacy (perfect for here and now)—rather than the optimal design (the best or the most efficient in the long run)—of their original vehicles [10]. During these sessions, makers also voiced important concerns about sharing their ideas with the outside world by formalising making knowledge. They simply plainly asked the designers not to export their original ideas to other geographical and cultural contexts—not because of copyright considerations, but because they thought it would be inappropriate to copycat their machines in other geographical and technological settings (Figure 26).

Figure 24.

Discussing the concept of a “good machine design”—A.

Figure 25.

Discussing the concept of a “good machine design”—B.

Figure 26.

Discussing the students’ proposals.

4. Discussion

In line with the theme of this special issue, we turn towards immense challenges within the scope of the sustainable development goals [42] that design aims to address. Entrusted with such tasks, designers are expected to profoundly understand the local culture and needs facing the target population ([2], p. 18). In this essay, by scaling down to the local challenge of being mobile in a roadless area of the Russian hinterland, we use this experience to reconsider traditional design education and complement it with studies into the best local practices and know-how. Fieldwork experience, i.e., ethnographic observation of a very personal kind [43] obtained through immersion into an established living system of rural inhabitants, became a primary source of inspiration and hands-on training for design students fitting in perfectly with Lave and Wenger’s concept of situated learning as value-adding participation in communities of practice [14]. Through this theoretical lens, we explored what and how design students could learn from real-life encounters with grassroots autonomous design—completely different from widely promoted “modern” (“westernised”) design—as a response to the top–down push for innovation.

This study resonates with the following research discourses and contexts: circular economy; appropriate technology movement; user innovation studies; and maker and repair culture. While companies worldwide are gradually moving from being manufacturers of solid, physical products to providers of flexible services, there is a growing demand for fluid, adaptive design solutions that are increasingly engaged with the environment they operate within [44]. This puts a greater emphasis on designing for “circular living”, when products, in addition to being free from negative externalities such as waste and pollution, are expected to be in use as long as possible [45]. The portrayed modest “wheelhorses” made of machinery scrap and reliably working for 10–15 years in response to love and care from their users serve as a clear manifestation of circularity and an alternative form of a sustainable relationship with the local environment. In this vein, circularity, and particularly re-manufacturing, is not a concept but a practice that can be observed, documented and learned from. We thus echo Andrews ([46], p. 305) in arguing that designers are crucial to developing circularity as a new economic model and advocating for broader use of this model to facilitate design education for sustainability.

The objects and practices of low-tech creativity we discovered present the opposite to “imposed” sustainable behaviour [47,48,49] and contemporary “design for development” within the “appropriate technology” movement [50]: from within, through local knowledge and oral history, through personal craft and trial, by virtue of economic reasons. In a global context, the Pozhva jeep—simple, durable, not flawless but easy-to-maintain—is comparable to iconic and long-standing examples of appropriate technology [50,51]. Furthermore, Pozhva jeeps are a part of a grander narrative on connectivity to both the land and its people. In terms of maker culture, they bind together the resources and opportunities of the environment with the community of peers and their competencies to ensure daily mobility at microlevel.

5. Conclusions

Drawing from the experiences described in this essay, we may derive two groups of practical implications for design education from students’ and teachers’ perspectives.

First, the “using the world as the classroom” and “working with real-life problems” approach ([52], pp. 241–242) motivates and guides students to formulate the problem by deeply engaging with the local community. In this setting, they learn to understand the following: the relationship between people and technology, and between technology and environment; the need to relate technology to human needs and scale; and to determine the extent of external designerly interventions in the local culture—how much design is needed (if any)—based on the principles of ethical, appropriate and environmentally responsible design. For teachers, implementing this approach requires a strong research background to carefully choose the locality and community and special pedagogical training to provide sensitive supervision and guidance during the trip.

Second, global and local challenges require strengthening the multidisciplinary and multi-actor approach to environmental, economic and socio-cultural aspects in design education. For both students and teachers, this implies teamwork, where team members’ diversity goes beyond academic multi-disciplinarity and involves local experts as knowledge-keepers and stakeholders. Through observing real-life examples of place-based making and longstanding use and reuse, where both control over technology and responsibility for the environment are passed to the user, students, i.e., would-be designers, enter into the spirit of the system acting appropriately out of its own resources ([18], p. 165) and access the pool of user skills and resources designers must consider and approximate. This kind of teamwork would potentially extend the limits of design training towards working with complex socio–technical systems, and students could learn to practically appreciate otherness and advocate for culturally versatile understandings of sustainability.

Overall, field explorations, especially into the non-urban context, while not a new pedagogical approach, are worth becoming a compulsory part of (product and industrial) design education. For both teachers and students, the integration of field study into the curriculum on a permanent basis would allow transferring the traditional ideating-making-reflecting activities from the studio into a real-life setting. While we do not argue that field experience is enough to prepare would-be designers for dealing with the significant global challenges of the 21st century, it clearly contributes to the often missed or unrecognised plurality of existing practices and ways of living.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.U.-K.; methodology, S.U.-K.; software, A.R. (Alexandra Raeva); investigation, A.R. (Alexandra Raeva), A.R. (Anton Raev), I.S. and M.F.; data curation, A.R. (Alexandra Raeva), A.R. (Anton Raev), I.S. and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.U.-K., A.R. (Alexandra Raeva); writing—review and editing, S.U.-K., A.R. (Alexandra Raeva); visualization, A.R. (Alexandra Raeva), A.R. (Anton Raev); supervision, S.U.-K.; project administration, S.U.-K.; funding acquisition, S.U.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 17-78-20047.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the hospitable community of Pozhva village. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the member of the research team Ilya Abramov, who provided his field data for further analysis and interpretation. The authors thank the organizers and reviewers of the ”Emerging Scholars Workshop”, particularly Jane Connory, Gizem Öz, Mayane Pereira Dore and Anh-Ton Tran for their thoughtful comments and recommendations on the earlier version of this essay that helped authors to develop the manuscript. The authors also thank three anonymous reviewers who provided constructive feedback that helped to improve the quality of the paper. Finally, the authors thank Valery Gafurov for his advice in literacy and for carefully proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in: the design of the study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

References

- Papanek, V.J. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change, 2nd ed.; Completely rev.; Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.W.; Norman, D. Changing Design Education for the 21st Century. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2020, 6, 13–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, V.A.; Pavlovskaya, E.E. Ural State University of Architecture and Art Research notes on the problems of higher design education in Russia. Vestnik Tomsk. Gos. Univ. Istor. 2019, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosstat. Otsenka Chislennosti Postoyannogo Naseleniya na 1 Yanvarya 2021 g. i v srednem za 2020 g [Estimated Resident Population as of January 1, 2021 and on Average for 2020]. 2021. Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/compendium/document/13282 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Campbell, A.D. Lay Designers: Grassroots Innovation for Appropriate Change. Des. Issues 2017, 33, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyysalo, S.; Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S. The user dominated technology era: Dynamics of dispersed peer-innovation. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenyuk, S.; Hyysalo, S.; Whalen, J. Proximal Design: Users as Designers of Mobility in the Russian North. Technol. Cult. 2016, 57, 866–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Garin, N.; Klyusov, N.; Dedevich, N.; Pokataeva, M. Light, Local, Repairable: A Designerly Exploration into an Ideal All-Terrain Vehicle. Int. J. Des. Objects 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Klyusov, N.; Hyysalo, S.; Klimenko, V. Depending on Users: The Case of Over-Snow Motorized Transport in Russia. ICON 2020, 2, 76–102. [Google Scholar]

- Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Hyysalo, S. Local adequacy as a design strategy in place-based making. CoDesign 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education; The Macmillan Company: London, UK, 1916; Available online: http://archive.org/details/democracyandedu00dewegoog (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.S.; Collins, A.; Duguid, P. Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning. Educ. Res. 1989, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Saidani, M.; Yannou, B.; Leroy, Y.; Cluzel, F. Dismantling, remanufacturing and recovering heavy vehicles in a circular economy—Technico-economic and organisational lessons learnt from an industrial pilot study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Tripathy, S.; Jena, S. Remanufacturing for the circular economy: Study and evaluation of critical factors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschnir, K. Ethnographic Drawing: Eleven Benefits of Using a Scketchbox for Fieldwork. Vis. Ethnogr. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Designs for the PluriverseRadical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, A.I.; Ramos, M.J. New graphics for old stories: Representation of local memories through drawings. In Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Ethnography; Pink, S., Kürti, L., Afonso, A.I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bijker, W.E. Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs: Toward a Theory of Sociotechnical Change; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Norcliffe, G. G-COT The Geographical Construction of Technology. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2009, 34, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.R. Lonely Ideas: Can Russia Compete? MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hippel, E. Democratizing Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Grassroots Innovation Movements; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kohtala, C.; Hyysalo, S.; Whalen, J. A taxonomy of users’ active design engagement in the 21st century. Des. Stud. 2020, 67, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, R.M.; Noel, L.-A.; Murphy, L. (Eds.) Proceedings of Pivot 2020: Designing a World of Many Centers; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/conference-volumes/37 (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Dourish, P.; Lawrence, C.; Leong, T.W.; Wadley, G. On Being Iterated: The Affective Demands of Design Participation. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Globalization; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.; Evans, M.; Mullagh, L. Meaningful practices: The contemporary relevance of traditional making for sustainable material futures. Craft Res. 2019, 10, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, P.; Kokko, S. Craft as cultural ecologically located practice: Comparative case studies of textile crafts in Cyprus, Estonia and Peru. Craft Res. 2017, 8, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Luckman, S.; Willoughby-Smith, J. Creativity without Borders? Rethinking remoteness and proximity. Aust. Geogr. 2010, 41, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardener, E. ‘Remote areas’: Some theoretical considerations [reprint 1987]. HAU J. Ethnogr. Theory 2012, 2, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, C. The changing significance of remoteness in contemporary Russia. Ètnografičeskoe Obozr. 2014, 3, 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kuklina, V.; Holland, E. The roads of the Sayan Mountains: Theorizing remoteness in eastern Siberia. Geoforum 2018, 88, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G. The Second Economy of the USSR. In The Underground Economy in the United States and Abroad; Tanzi, V., Ed.; Lexington Books: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1982; pp. 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G. Informal Personal Incomes and Outlays of the Soviet Urban Population. In The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries; Portes, A., Castells, M., Benton, L.A., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: London, UK, 1989; pp. 150–170. [Google Scholar]

- Barsukova, S.; Radaev, V. Informal Economy in Russia: A Brief Overview. J. Econ. Sociol. 2012, 13, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubev, A.; Smolyak, O. Making selves through making things. Cah. Monde Russe 2013, 54, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimova, E.; Chuikina, S. The Repair Society. Russ. Stud. Hist. 2009, 48, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, V.; Trogal, K. Repair matters. Ephemer. Theory Politics Organ. 2019, 19, 203–227. [Google Scholar]

- Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Akimenko, D.; Garin, N.; Mietteinen, S. Arctic Design: Basic Concepts and Practice of Implementation. In RELATE NORTH: Tradition and Innovation in Art and Design Education; International Society for Education Through Art—InSEA: Rabat, Morocco, 2020; pp. 14–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World, United Nations: Sustainable Development Goals. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Suri, J.F. Poetic Observation: What Designers Make of What They See; Springer: Singapore, 2011; pp. 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson, O.; Eckert, C. Product Development 2040—Technologies Are Just as Good as the Designer’s Ability to Integrate Them. Des. Soc. 2020, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy Volume 2: Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector. 2013. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Andrews, D. The circular economy, design thinking and education for sustainability. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burningham, K.; O’Brien, M. Global Environmental Values and Local Contexts of Action. Sociology 1994, 28, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.; Harrison, C.M.; Filius, P. Environmental Communication and the Cultural Politics of Environmental Citizenship. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 1998, 30, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barr, S. Strategies for sustainability: Citizens and responsible environmental behaviour. Area 2003, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, R. Radical Plumbers and PlayPumps. Objects in Development. PhD. Thesis, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Laet, M.; Mol, A. The Zimbabwe Bush Pump: Mechanics of a Fluid Technology. Philos. Lit. J. Logos 2017, 27, 171–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontis, S.; van der Waarde, K. Looking for Alternatives: Challenging Assumptions in Design Education. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2020, 6, 228–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).