Abstract

Consumers’ purchasing choices are no longer based only on economic factors but also on ethical reasons related to environmental sustainability and food safety. However, nutritional information on food labels is underused by consumers. Often the lack or incompleteness of information available on the market obstructs the complex transition towards sustainable consumption patterns. This empirical study analysed a sample of 359 consumers from an area in Southern Italy (city of Naples) to identify homogeneous consumer clusters with respect to the assessment of the level of consumer attention to sustainable environmental, social behaviours in daily life, and also to safety attributes. The most important sources of information influencing the consumers’ choices, food safety knowledge, and future purchasing behaviour were analysed. The research sample was self-selected, and the questionnaire for the survey was administrated through a non-probability sample from a reasoned choice. The results indicate that the ideal solution is a five-cluster partition that confirms a good level of attention to intrinsic attributes, in particular food expiry, transparency of food information, food traceability, and seller confidence. In addition, the research could provide an opportunity to consider collaborative actions between policy makers and industries to increase consumer awareness of environmental attributes.

1. Introduction

The modern agri-food consumers are more inclined to make informed and conscious purchasing decisions regarding products that favour a level of environmental, social, and economic sustainability while not neglecting economic aspects [1,2]. Numerous studies highlight the lack of or incomplete information available on the market that creates [3] information asymmetry issues that obstruct the complex acquisition of sustainable consumption patterns [4]. According to recent studies [5,6,7], the nutritional value of food remains a key factor for consumers in their food purchases. Nevertheless, even when nutritional information on food labels is comprehensive, it is underused by consumers [8,9].

The agri-food sector attaches great importance to the quality of raw materials, with respect for and protection of the environment and human resource, involving the stakeholders [10,11,12]. Consumers’ choices are also ethical choices related to the protection of the environment and working conditions, protecting the territory and resources to be handed over to future generations [13]. Consumers do not base their purchasing choices only on economic motivations in relation to quality/price [14,15,16,17,18,19,20] but, above all, on the benefits to the community for the development of a more environmentally friendly society. Important international reports, such as the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science, and Technology (IAASTD); the Climate Change Manifesto; and the Future of Food Safety [21], highlight the link between food security and environmental sustainability.

This connection is explained in these studies by stating that agriculture has a fundamental footprint on all major environmental issues [22,23]: climate change, biodiversity, land degradation, water quality, etc. These issues present difficult development challenges that need to be resolved because we must reduce the climate change footprint of agriculture; we must not degrade our soil and water, which has negative effects on biodiversity. [24,25]. These major challenges can be addressed by integrating local and traditional knowledge with institutional knowledge.

The new needs expressed by consumers and acknowledged by the actors of the production chain and in synergy with national governments encourage the development of increasingly articulated certification systems [26,27]. In the context of the green economy, such products have higher costs to operate in an ecological and social way. A good digital green marketing strategy and a good use of social media as a communication channel are essential to communicate the value of the product and to achieve a higher level of civic engagement [28]. The aim is to encourage the purchase of eco-friendly products and therefore more ethical than those with only economic benefits.

This study aims to analyse the degree of awareness of a sample of 359 Italian consumers regarding the adoption of sustainable behaviour in their lifestyle and attention to food safety attributes. In addition, it analyses the consumer’s understanding of the main sources of information and their influence on the respondent’s food safety knowledge and future purchasing behaviour.

2. Theoretical Framework

Food has an essential role in society by influencing people’s lifestyle, health, and habits [29] and is an essential part of socialization. Today, the consumer defined as “critical” or “responsible” can show his or her attention to food safety, environmental protection issues, justice, human rights, and everything related to the ethical content of commercial activities to the production world [30,31].

In addition, the critical consumer avoids products that are dangerous to the health or cause damage to the environment during manufacture, use, or disposal. In this context, there are many events that focus on the valorisation and importance of food. For example, Expo 2015 “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life” connected food issues with sustainability [32,33,34]. This event analysed the role of food in addressing nutrition, food production, management, and distribution as well as global and regional food governance, promoting an international dialogue on nutrition and natural resources. Furthermore, some studies [35,36] have supported that gastronomy can help build social relationships with local communities by clarifying the different motivational factors that drive consumers to choose experiences that promote a healthy lifestyle. According to Beldad and Hegner (2018) [37], the propensity toward purchasing food safety products is higher among women than men, as women are more willing to pay more. According to Monier-Dilhan (2018) [38], consumers with higher levels of education are more likely to buy organic products for health reasons, product quality, and environmental protection [39]. In accordance with previous studies, [40] the level of education is rather more relevant [41] than the age variable in obtaining a good level of attention to food safety issues. In the field of communication, according to Panagiotopoulos et al., (2015) [42], before digital media, food companies had to use expensive marketing media to reach their audience with limited feedback and low possibility of target knowledge.

Since the 2000s, digital green marketing strategies related to the optimal and widespread use of social media to effectively promote product value have become widely established [43,44]. However, previous studies show that employees (especially if they are married) use social media much less and are more sceptical about this digital evolution [45].

Academic research is developing, and related concepts are being explored, such as the impact of such information sources on consumers’ purchasing motivations [46]. The aim is to induce consumers’ purchasing motivations towards more sustainable and environmentally friendly products. Based on these assumptions, agri-food systems are seeking new levels of sustainability to respond to new levels of wellbeing to monitor the health of the planet [47,48].

The study focuses on the following Research Questions (RQs):

RQ1: The level of consumer attention to intrinsic attributes of the product purchased and the reasons for purchasing food products.

RQ2: The implementation of sustainable environmental and social behaviours in the daily life of respondents.

RQ3: The most important sources of information that influence the consumer’s choices.

3. Materials and Methods

This study investigates the respondents’ level of awareness of sustainable behaviours in their daily lives, consumers’ understanding of and attention to intrinsic attributes, and the influence of information sources on future purchasing behaviour. To collect information, a questionnaire was prepared for a population of 359 Italian consumers residing in Campania (a southern Italian region), surrounding the city of Naples. The interviews were conducted directly face-to-face during the period January–February 2021.

The research sample was self-selected; it was an exploratory study without inferential objectives. The questionnaire was administrated through a non-probability sample from a reasoned choice.

The final questionnaire was divided into four sections consisting of multiple-choice questions measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 points. The first part investigated the safety of food consumed while the second part the tendency to implement sustainability-oriented behaviours in the daily lives of respondents.

In addition, the greater willingness to purchase food products when food safety-oriented production behaviours are adopted was analysed. Lastly, which sources of information on food, between mass media and social media, were most appreciated by the interviewees was analysed, highlighting a possible influence of information sources on future purchasing behaviours. Using the data from the questionnaires, a first univariate exploratory analysis was elaborated (analysis of the frequency and use of synthetic indicators), then a multivariate analysis [49], and an analysis of the main components and cluster analysis were performed. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used as a way of reducing dimensionality [50]. It made it possible to restrict the number of quantitative variables into a smaller set of factors or principal components (PCs). After identifying the key components (with PCA analysis) that influence the awareness of respondents on intrinsic attributes, a cluster analysis was finalized [51] to segment the statistical units [52,53]. In this scheme, the K-means approach was chosen, in which objects were divided into separate sub-sets, and each object is part of one and the same cluster. With this analysis, an ideal partition of 5 clusters was identified, analysed, and discussed.

4. Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The consumers participating in this study were mostly single, employed women (57.66%), aged between 18 and 25, with a high school diploma and a total net annual income of 10,000–20,000 €. It can be assumed that the female population is still responsible for food purchase [54], according to the study of Beldad and Hegner (2018) [37].

Table 1.

Socio-demographic variables of the sample.

The sample of respondents is “very” concerned (35.9%) about food safety standards, with more attention paid to aspects such as food expiry (33.1%) and transparency in food information (28.69%). Other aspects, such as food traceability (29.53%) and seller confidence (31.5%), were only “moderately important”. From the sample interviewed, it was shown that among the most considered purchasing motivations were the place of origin (28.69%) and the presence of certifications (23.96%), while the method of production (28.97%) and the method of conservation (24.79%) were of “moderate importance”. The questions in the second part of the questionnaire investigated the use of sustainable behaviour adopted daily by citizens, and 28.41% stated that the habit of buying eco-labelled products is “very important” in their daily lives. The purchase of fair-trade products and the use of eco-labels are still niche issues, according to Monier-Dilhan (2018) [38] and Van’t Veld (2020) [39]. In the third survey section, respondents were asked how much more they would be willing to spend in the purchase of a product if the company adopted food safety behaviours. Looking at the responses, 48.75% said they would be willing to spend at least 10 % more than the average selling price for products with safety attributes; 30.92% said they would be willing to spend at least 20% more than the average price; 25.07% stated that they would have “moderate” willingness to spend 30% more than the average selling price.

The final part of the survey questions investigated on the information sources on food safety evaluating their level of clarity and reliability. First, the information sources with most clarity and reliability were doctors (34.54%), Ministry of Health (30.08%), and health associations (28.69%), while the least reliable were the food blogger (32.59%) and social media (32.59%), whose clarity and reliability were evaluated “for nothing”. Looking at traditional media, we can see that TV (34.26%), the Internet (31.48%), and magazines (33.43%) present a “moderate” score.

In this fourth section of the questionnaire, the influence of information sources on the future purchasing behaviour of the respondents was investigated. In addition, how the reputation of food companies influences the respondents’ cultural enrichment on food safety matters was investigated. The results showed that 30.92% of the sample buy food safety products having been influenced by the source of information, while 33.15% are influenced to a “moderate” extent in their purchase by the reputation of the companies, and 30.64% of the sample are “very” inclined to acquire more information about environmental and social sustainability, according to Van’t Veld (2020) [39].

4.1. Principal Component Analysis

The sensitization of the sample on the topics of food safety and the related propensity towards greater purchase is influenced by several variables. Therefore, the use of principal component analysis provides an overall clearer and more immediate interpretation [50]. In particular, the components identified can be interpreted as follows:

- Purchasing motivations describe the consumer purchasing motivations on food products, such as place of origin or method of production.

- Sustainable behaviour describes the implementation in daily life of the interviewees whose behaviour is strongly oriented toward sustainability, for example, the purchase of fair-trade products and the use of trademarks protecting workers.

- Propensity to purchase describes consumer’s willingness to pay for a food safety product.

- Attention to safety attributes is a component that describes the principal attributes for which consumers pay more their attention, for example, food expiration and food traceability.

- Media sources satisfaction describes the consumers comprehension of the informative source for a food safety product. In this component, we discuss traditional media, such as TV, the Internet, and magazines.

- Awareness is a component that describes if the information source is influencing the consumer’s food safety knowledge and future buying behaviour.

- Institutional sources satisfaction describes the consumers comprehension on the informative source for a food safety product. In this component, we talk about doctors, Ministry of Health, and health associations.

- Social media satisfaction describes the consumers comprehension of the informative source for a food safety product. In this component, we talk about social networks and food bloggers.

The choice of the number of components occurs by considering three joint criteria: values of community, the amount of cumulative variance explained by the factors (Table 2), and the Eigenvalues of the components. The eight principal components thus identified (Table 3), in fact explain 65.929% of the variance in the original variables.

Table 2.

Total of the explained variance.

Table 3.

The rotated component matrix.

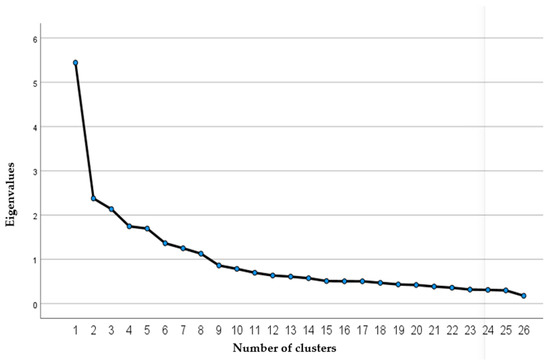

The values of community explain the amounts of variance of each variable explained by extracted factors and such values, being always greater or equal to 50% of the initial variance, demonstrate the fact that the variables are well represented by the factors. The scree plot constructed (Figure 1) shows a slope change at the point where the components become negligible, demonstrating the fact that the first eight factors are explicative since they presented an Eigenvalue greater than 1.

Figure 1.

The scree plot. Source: Authors’ elaboration of data from survey.

4.2. Cluster Analysis

In this empirical survey, the ideal solution is a five-cluster partition, and Table 4 presents the final cluster centres. Having identified the key components that influence the sensitization of the interviewees to the topics analysed, the aim of a cluster analysis was [55] to segment the statistical units [56].

Table 4.

The final cluster centres.

The clusters can be described as follows:

- Cluster 1 can be defined in summary as the group of “food safety virtuous”, represented by 20.05% of the sample (72 of 359 consumers) and characterized mainly by component 3 (value of 0.81462). In fact, their propensity to buy food safety products is much higher, and their motivation to buy them is considerable. They are sustainable in their daily life and present a good level of comprehension of information sources, such as the traditional media, while having a negative level of social media satisfaction (−0.01540).

- Cluster 2 can be defined in summary as the group of “consumer sensitivity” to institutional information. The propensity to purchase and the purchasing motivations are negative in respect to all the components evaluated, especially with reference to orientation towards sustainability. This cluster is more numerous, comprising 106 of 359 interviewees (29.52% of the sample) and is extremely far from component 3 (value of −0.03139), named propensity to purchase. The component 8 (social media satisfaction) presents a negative value (−0.29603), while component 7 (Institutional sources satisfaction) presents a positive value (0.41438).

- Cluster 3 can be defined as the group of “sceptical consumer”, representing 14.76% of the sample (53 of 359 consumers) and is extremely far from component 7 (value of −1.18549). Therefore, this means that the cluster does not trust institutional sources for food product safety information. This clustering is the least numerous with an elevated awareness level (component 6 with value of 0.79324) and positive social media satisfaction (component 8 with value of 0.52680). However, there is no willingness to pay more for a food safety product because propensity to purchase (component 3) presents a negative value (−0.31679).

- Cluster 4 can be defined as the group of “social media consumer” since this consumer does not pay attention to sustainability and to food safety; they choose to maintain a motivation purchase (component 3 with a positive value) based on social media information rather than mass media. This cluster represents 57 consumers out of 359 (14.48%) and is characterized mainly by component 8, social media satisfaction (value of 1.28354), and it is extremely far from component 5 (media sources satisfaction with value of −0.80027).

- Cluster 5 can be defined as the group of “distrustful consumer” since they do not see the information source as an advantage and an opportunity to be followed. In fact, component 3, propensity to purchase, presents a negative value. This cluster comprises 76 consumers out of 359 (21.16 %) and is characterized mainly by component 1 (purchasing motivations with value of 0.63766), but the most negative components evaluated are number 8, the social media satisfaction (value of −0.81811) and component 5 (media sources satisfaction with value of −0.59981).

The ANOVA table shows which variables contributed the most in the identification of the clusters. Social media satisfaction, purchasing motivations, and media sources satisfaction are the three variables associated significantly with the clusters identified. These are followed by institutional sources satisfaction and propensity to purchase. However, attention to food safety and sustainable behavior are the least influential in the division of the groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

ANOVA table.

Table 6 and Table 7 show the composition of the cluster groups according to socio-demographic variables. Cluster 1 composed of 72 statistic units (20.5% of the sample) and includes a concentration of unmarried females (age 18–25 years old, 32% of the consumers). Regarding instruction, most of the sample have a diploma and are represented by students (32% of the sample), while 43% have an income between 10,000 and 20,000 euros. This cluster presents the highest level of instruction in the survey because the percentage of degrees and postgraduates is more than 30%. This important information confirms the theory concerning a higher attention to food safety based on education level, according to the study by Monier-Dilhan (2018) [38], because cluster 1 is the most virtuous of all concerning food safety issues. In addition, it is confirmed that the education of women is fundamental in the sensitization and promotion of food safety issues, according to Beldad and Hegner (2018), [37] because this cluster presents a higher concentration of women graduates.

Table 6.

Composition of cluster groups I, II and III.

Table 7.

Composition of cluster groups IV and V.

In cluster 2, composed of 106 units (29.52% of the sample), the distribution with respect to age is the same as cluster 1, but the age class 18–25 is more numerous with 46 units (43.39% of the sample), with a good percentage of the students (40.56%) having a diploma. This cluster has a higher concentration of young people and men (that represent 46.22% of the sample with 49 statistic units), but at same time, it has the worst instruction level because only 11% have a degree or are postgraduates. In addition, it is also the cluster that presents the worst incomes because only 31 units out of 106 earn more than 20,000 euros. This confirms the theory (Vlontzos et al., 2018) [57] that young people (mainly the men) earn less than adults, do not show an interest in the food safety issues, and do not have an increasing propensity to purchase. Therefore, this cluster is the most negative regarding food safety attention, and it needs more sensibilisation on these issues.

In cluster 3 (N = 53), 56% of the consumers are unmarried women in the age group between 18 and 25 years; the prevalent level of education is the diploma, while their income is medium-high, with 44% of these consumers (24 statistic units) earning over 20,000 euros p.a.

In fact, this is the potentially interesting cluster in food safety issues because they present a good predisposition to sustainability behaviours and a positive attitude versus food safety attributes. Although their incomes are very high, there is no predisposition to increase their purchase of food safety products. This could be due to a low level of instruction; in fact, only 18% (10 statistic unit) have a degree or are postgraduates.

Cluster 4 is composed of 52 statistic units (14.48%), mainly of female students with a diploma. In this cluster, the percentage of married women is relevant, nearly 50%. This group is defined as the group of “social media consumer” since they do not think that attention to food safety is a goal to be pursued for sustainability; they choose to maintain a motivation purchase based on social media, according to Heinonen 2011 [58]. This point is particularly important to demonstrate that age is not a relevant variable for a good level of attention to food safety issues, according to previous studies [40,59], confirming that instruction level is rather more fundamental [41].

Finally, cluster 5 composed of 76 units (21.16% of the sample), including mostly married consumers, with a percentage of 53.94 (41 units). This group is characterized mainly by women in the age group of 18–25 years and who are prevalently employees. This cluster shows the dissatisfaction versus the source’s information (mainly social media), and this could confirm the theory that employees (especially if married) spend less time on social media and so are more sceptical of this digital evolution [45]. Their motivation to purchase is quite solid, and their sustainable behaviour discreet, but the cluster does not show them to be believers in the food safety information sources (media and social media) to obtain the achievement of sustainability.

4.3. Discussion

For three of the five cluster groups, attention to food safety has a positive value with respect to sustainable behaviour and purchasing motivations. In addition, consumers’ level of education (university degree or postgraduate degree), when accompanied by high levels of earnings and employment status, increases the level of attention to the quality of food consumption and the link between food and health, according to Monier-Dilhan (2018) [38]. Regarding the information sources, the consumers show a preference for institutional sources, so four out of five clusters present a positive value for this attribute, while for social media, only two clusters out of five present a positive value. The fundamental role is attributed to educated women (more virtuous, in the cluster 1) who present a higher level of attention to food safety issues, preferring institutional sources to media sources, according to Beldad and Hegner (2018) [37], and with a good propensity to purchase food safety products. This survey reveals that the classic role of the consumer has been surpassed and that the consumer is now seen as an active producer of corporate value. In particular, the study by Heinonen (2011) [58] shows that consumer behavior is not exclusively influenced by traditional marketing communications. Therefore, companies can be expected to participate more in the activities of their target groups on social media to understand the impact of social media on their brand and their image. However, digital marketing in the circular economy and optimal use of social media still have a long way to go to educate, inform, and engage consumers in sustainability. Duit and Galaz and Walker et al., (2008) [60,61] affirm that to meet the challenges of current society, more sustainable approaches, such as new management and governance systems, are needed, especially for consumers who are not very active online and commonly show a low level of participation and contribution on social media, according to Schau (2009) [62]. However, other studies have drawn attention to the importance of social networking (Schau et al., 2009) [63]. The negative effect of lower income on food consumption decisions, evidenced in this empirical research, can be compensated for by food safety education. Especially for young people (males), it is necessary to promote ad-hoc information programmes within the formal educational processes since, according to the study by Vlontzos et al., (2018) [57], they are the ones most influenced by the media in their purchasing decisions.

In Italy, this issue has been approached by the Ministry of Health, which, to raise the level of food safety information among young people, proposes a link between food risk communication and social media [43,64]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) risk communication guidelines mentions that social networks should inform and involve stakeholders in communicating easy and clear messages to a wide variety of consumers. It provides information to consumers so that they are more aware of the risks associated with a food product. The aim is to establish confidence in risk assessment through accurate and appropriate information. This allows consumers to choose from a variety of options that may meet their risk criteria.

These messages are also effectively spread through “online community discussions” that influence consumer behavioural change.

According to Heinonen (2011) [58], this can be achieved by promoting discussions on different everyday purchasing choices and encourage consumers to ask questions and share experiences. Relating the offer to consumers’ daily lives in this way can also promote the food company and its image. Through consumer engagement and information sharing on social media, it is possible to obtain real-time product reviews, inviting consumers to share their opinions.

Information shared on social media plays a key role in improving consumer empowerment and knowledge in the food industry (Stefanidis et al., 2013) [65,66]. According to Dijkmans et al., (2015) [67], companies’ engagement in the promotion of their products through the optimal use of social media increases and facilitates the development of a company’s corporate reputation.

Consequently, the use of social networks should be a strategic part of food risk communication projects. The results of this empirical analysis can support the companies in the introduction of new marketing strategies to propagate emerging food safety trends among post-modern consumers.

5. Conclusions and Political Implications

The study confirms a good level of attention towards intrinsic attributes, especially for all the aspects concerning food expiry, transparent food information, food traceability, and seller confidence. Although the purchase of environmentally friendly products is increasing, there are still many consumers who do not use a high degree of environmental sustainability as a purchasing parameter.

The results of this study may stimulate the strengthening of information campaigns to increase food safety knowledge and improve awareness levels in consumer choice. Moreover, research may contribute to the understanding how social media can affect consumer awareness of environmental and social sustainability and of intrinsic attributes to define a business strategy. In addition, such studies could provide an opportunity to consider collaborative actions between institutions and industries to increase consumer awareness of environmental attributes. The work presents some limitations with reference to empirical research: the numerosity of the samples of consumers analysed (defined with random criteria) as well as the reference context (Naples, Italy). Possible future developments of the research could extend the analysis of consumers over the entire Italian territory in order to evaluate in more detail all the dynamics for the achievement of sustainable consumption models as well as designing an empirical survey that evaluates the sensitivity to the issue (intended as willingness to spend, role of online/offline communication channels, and so on), showing more differences (if existing) between males and females by analysing the level of awareness of sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; methodology, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; software, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; validation, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; formal analysis, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; investigation, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; resources, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; data curation, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; writing—review and editing, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; visualization, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; supervision, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S.; project administration, G.C., V.R., D.S., and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pengue, W.A.; Gemmill Herren, B.; Balázs, B.; Ortega, E.; Acevedo, F.; Diaz, D.N.; Díaz de Astarloa, D.; Fernandez, R.; Garibaldi, L.A.; Giampietro, M.; et al. Eco-agri-food systems: Today’s realities and tomorrow’s challenges. In TEEB for Agriculture & Food: Scientific and Economic Foundations; UN Environment: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Chapter 3; pp. 57–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Thorn, J.P.R.; Gowdy, J.; Bassi, A.; Santamaria, M.; DeClerck, F.; Adegboyega, A.; Andersson, G.; Augustyn, A.M.; Bawden, R.; et al. Systems Thinking: An Approach for Understanding ‘Eco-Agri-Food Systems’; The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Langen, S.K.; Vassillo, C.; Ghisellini, P.; Restaino, D.; Passaro, R.; Ulgiati, S. Promoting circular economy transition: A study about perceptions and awareness by different stakeholders’ groups. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. La Globalizzazione che Funziona [Making Globalization Work]; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.M. Mediating influences of attitude on internal and external factors influencing consumers’ intention to purchase organic foods in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hati, S.R.H.; Zulianti, I.; Achyar, A.; Safira, A. Perceptions of nutritional value, sensory appeal, and price influencing customer intention to purchase frozen beef: Evidence from Indonesia. Meat Sci. 2021, 172, 108306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.S.; Cassady, D.L. The effects of nutrition knowledge on food label use. A review of the literature. Appetite 2015, 92, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D.; Rotondo, G. Consumer attitudes to food labelling: Opportunities for firms and implications for policymakers. Calitatea 2015, 16, 312. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, I.; Hasnaoui, A. The meaning of corporate social responsibility: The vision of four nations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, V. Not Just Food: The, New, Importance of Urban Gardens in the Modern Socio-Economic System: A Brief Analysis; Ledizioni: Milan, Italy, 2015; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpato, D.; Civero, G.; Rusciano, V.; Risitano, M. Sustainable strategies and corporate social responsibility in the Italian fisheries companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2983–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civero, G.; Rusciano, V.; Scarpato, D. Orientation of Agri-Food Companies to CSR and Consumer Perception: A Survey on Two Italian Companies. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2018, 9, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Fraedrich, J. Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making & Cases; Nelson Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fabris, G. Il Nuovo Consumatore: Verso il Postmoderno; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2003; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Unnevehr, L. (Ed.) Food Safety in Food Security and Food Trade; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpato, D.; Simeone, M.; Rotondo, G. The challenge of Euro-Mediterranean integration for Campania agribusiness sustainability. Agric. Econ. 2019, 6, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A. A pluralistic approach to economic and business sustainability: A critical meta-synthesis of foundations, metrics, and evidence of human and local development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Micheletti, S.; Bosone, M. A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Son, M.; Hong, A.J. Trends in Civic Engagement Disaster Safety Education Research: Systematic Literature Review and Keyword Network Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Mora, C.; Chryssochoidis, G.; Kehagia, O. Rintracciabilità, qualità e sicurezza alimentare nella percezione dei consumatori. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2010, 12, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisco, G.; Gatto, A. Climate Justice in an Intergenerational Sustainability Framework: A Stochastic OLG Model. Economies 2021, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. China, and the UN Food System Summit: Silenced Disputes and Ambivalence on Food Safety, Sovereignty, Justice, and Resilience. Development 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilbeck, A.; Tisselli, E. The emerging issue of “digitalization” of agriculture. In Transformation of Our Food Systems; Herren, H.R., Haerlin, B., The IAASTD+ 10 Advisory Group, Eds.; Zukunftsstiftung Landwirtschaft: Bochum, Germany, 2020; Chapter 59. [Google Scholar]

- Turnhout, E.; Duncan, J.; Candel, J.; Maas, T.Y.; Roodhof, A.M.; DeClerck, F.; Watson, R.T. Do we need a new science-policy interface for food systems? Science 2021, 373, 1093–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, P. Rintracciabilità obbligatoria e rintracciabilità volontaria nel settore alimentare. Dirit. E Giurisprud. Agrar. E Dell’ambiente 2005, 3, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier, C.; Valceschini, E. Coordination for traceability in the food chain. A critical appraisal of European regulation. Eur. J. Law Econ. 2008, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Gatto, A. The puzzle of greenhouse gas footprints of oil abundance. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 75, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M. Seeking Gastronomic, Healthy, and Social Experiences in Tuscan Agritourism Facilities. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Ferrari, M. Environmental policy stringency, technical progress and pollution haven hypothesis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusciano, V.; Civero, G.; Scarpato, D. Social and ecological high influential factors in community gardens innovation: An empirical survey in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civero, G.; Rusciano, V.; Scarpato, D. Consumer behaviour and corporate social responsibility: An empirical study of Expo 2015. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1826–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, G.; Licciardo, F.; Verrascina, M.; Zanetti, B. The Agroecological Approach as a Model for Multifunctional Agriculture and Farming towards the European Green Deal 2030—Some Evidence from the Italian Experience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massari, S. Transforming research and innovation for sustainability: Transdisciplinary design for future pathways in agri-food sector. In Transdisciplinary Case Studies on Design for Food and Sustainability; Woodhead Publishing: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Civitello, L. Cuisine and Culture: A History of Food and People; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Q.L.; Ab Karim, S.; Awang, K.W.; Bakar, A.Z.A. An integrated structural model of gastronomy tourists’ behaviour. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldad, A.; Hegner, S. Determinants of fair-trade product purchase intention of Dutch consumers according to the extended theory of planned behaviour. J. Consum. Policy 2018, 41, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monier-Dilhan, S. Food labels: Consumer’s information or consumer’s confusion. OCL 2018, 25, D202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van’t Veld, K. Eco-labels: Modeling the consumer side. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Prescott, J. A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, G.E.; Abidin, U.F.U.Z.; Lihan, S.; Jambari, N.N.; Radu, S. A cross sectional study on food safety knowledge among adult consumers. Food Control 2019, 99, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, P.; Shan, L.C.; Barnett, J.; Regan, Á.; McConnon, Á. A framework of social media engagement: Case studies with food and consumer organisations in the UK and Ireland. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Sustainable consumption: How does social media affect food choices? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.C.; Wu, L.W.; Chang, Y.Y.C.; Hong, R.H. Influencers on social media as References: Understanding the Importance of Parasocial Relationships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J.K.; Iyer, R.; Eastman, K.L.; Gordon-Wilson, S.; Modi, P. Reaching the price conscious consumer: The impact of personality, generational cohort and social media use. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šikić, F. Using Instagram as a Communication Channel in Green Marketing Digital Mix: A Case Study of bio&bio–Organic Food Chain in Croatia. In The Sustainability Debate; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, P.; Galaz, V.; Boonstra, W.J. Sustainability transformations: A resilience perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, L.; Karpouzoglou, T.; Doshi, S.; Frantzeskaki, N. Organising a safe space for navigating social-ecological transformations to sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6027–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilg, A.; Barr, S.; Ford, N. Green consumption, or sustainable lifestyles? Identifying the sustainable consumer. Futures 2005, 37, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M.; Romagnoli, L. Customer satisfaction with farmhouse facilities and its implications for the promotion of agritourism resources in Italian municipalities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Lillo, A. Analisi Multivariata per le Scienze Sociali; Pearson Italia Spa: Turin, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, T.A.; Siegrist, M. A consumer-oriented segmentation study in the Swiss wine market. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.; Fasanelli, R.; Riverso, R. Emotional profiling for segmenting consumers: The case of household food waste. Age 2019, 18, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Peta, E.A. Consumi Agro-Alimentari in Italia E Nuove Tecnologie; Quadro Strategico Nazionale; Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Dipartimento per le Politiche di Sviluppo e di Coesione, Unità di Valutazione degli Investimenti Pubblici (UVAL): Rome, Italy, 2007.

- Bollani, L.; Peira, G.; Pairotti, M.B.; Varese, E.; Nesi, E.; Pairotti, M.B.; Bonadonna, A. Labelling and sustainability in the green food economy: Perception among millennials with a good cultural background. Rev. Stud. Sustain. 2017, 2, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; D’Amico, M. Clustering attitudes and behaviours of Italian wine consumers. Calitatea 2014, 15 (Suppl. 1), 54. [Google Scholar]

- Vlontzos, G.; Kyrgiakos, L.; Duquenne, M.N. What are the main drivers of young consumers purchasing traditional food products? European field research. Foods 2018, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heinonen, K. Consumer activity in social media: Managerial approaches to consumers’ social media behavior. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todua, N.; Jashi, C. Influence of Social Marketing on the Behavior of Georgian Consumers Regarding Healthy Nutrition. Bull. Georgian Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 12, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Duit, A.; Galaz, V. Governance and complexity—Emerging issues for governance theory. Governance 2008, 21, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Barrett, S.; Galaz, V.; Polasky, S.; Folke, C.; Engström, G.; Ackerman, F.; Arrow, K.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chopra, K.; et al. Looming global-scale failures and missing institutions. Science 2009, 325, 1345–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Understanding the Appeal of User-Generated Media: A uses and Gratification Perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schau, H.J.; Muñiz, A.M.; Arnould, E.J. How Brand Community Practices Create Value. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Simeone, M. The growing influence of social and digital media: Impact on consumer choice and market equilibrium. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1766–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, A.; Cotnoir, A.; Croitoru, A.; Crooks, A.; Rice, M.; Radzikowski, J. Demarcating new boundaries: Mapping virtual polycentric communities through social media content. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A.; Drago, C. When renewable energy, empowerment, and entrepreneurship connect: Measuring energy policy effectiveness in 230 countries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 78, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkmans, C.; Kerkhof, P.; Beukeboom, C.J. A stage to engage: Social media use and corporate reputation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).