1. Introduction

A report by the World Health Organization [

1] uncovered the critical shortcomings that need immediate attention in Libyan hospitals: scaling up hygiene standards and healthcare waste collection and disposal, training of selected staff, technical support for disposal of large amounts of expired drugs and strengthening and developing medical waste management including waste segregation, collection, treatment, and disposal.

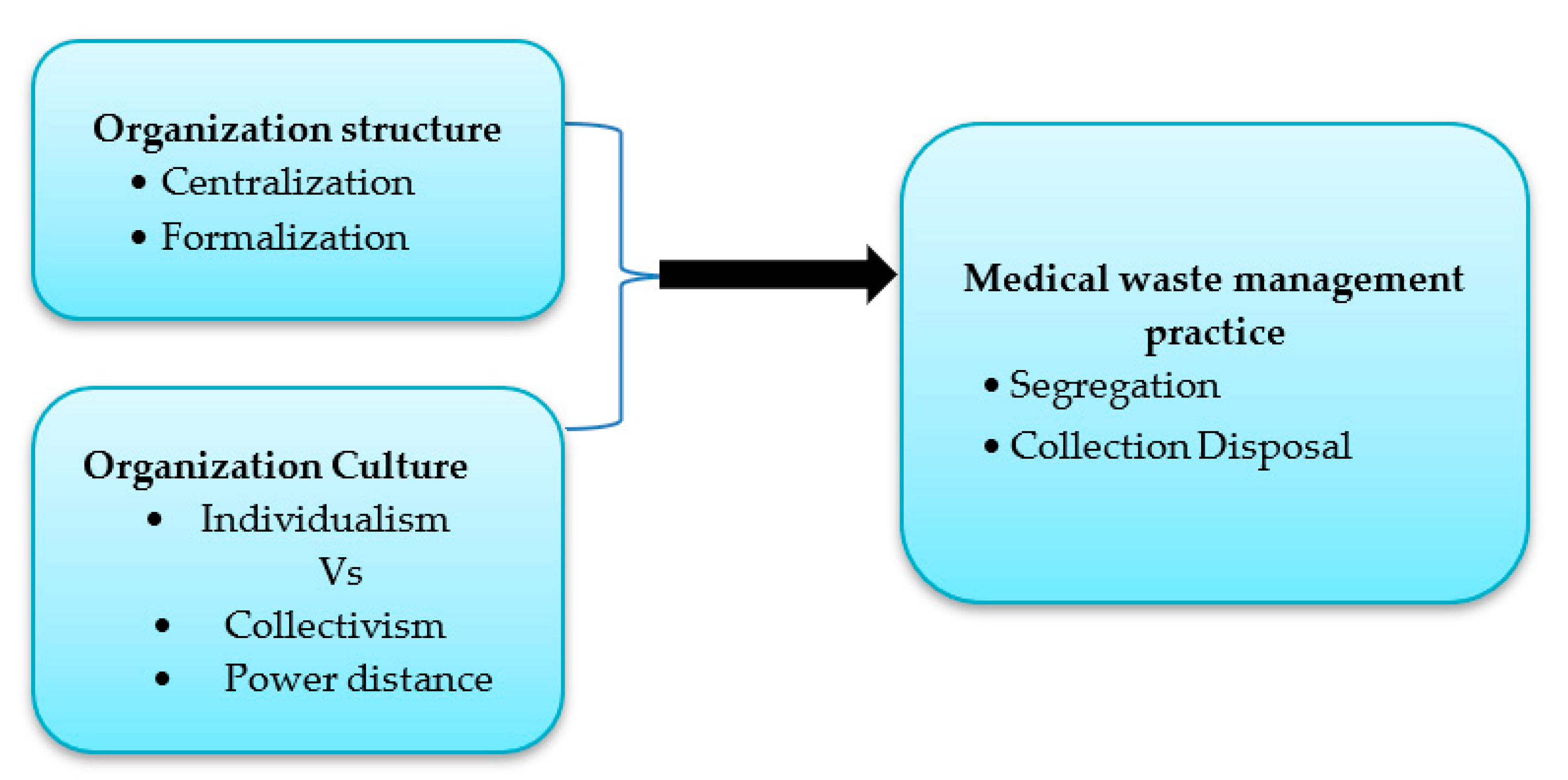

The basic assumption known by various scholars is that many organizational factors affect healthcare waste management practice. For instance, organizational structure is found to be a clear factor influencing healthcare waste management [

2]. Similarly, the author [

3] has classified organizational culture (OC) as human interaction and organizational arrangements. Some other previous research suggests that several factors will influence the management of healthcare waste [

4]. It is essential to consider the influence of the system components on each other to arrive at an optimal plan for the hazardous waste management system [

5]. Our findings illustrate that OC does have a significant impact on the adoption of HWMP. Furthermore, the authors [

6] asserted that centralization may reduce creative solutions and impede communication between departments and the sharing of ideas. This has a clear impact on healthcare facilities when, for example, a healthcare facility has accumulated expired medications that must be handled. On the other hand, a decentralized organizational structure can be more beneficial in allowing employees to bring in full participation for the building of spontaneous processes [

7].

The influence of internal and external factors such as culture and human factors on healthcare waste management practice have been investigated by existing studies [

8]; the factors that influence HWMP among the Libyan public hospitals have been given limited attention. Therefore, the present research is considered essential to many stakeholders in Libya who oversee the management of waste since the last update by the authors in their studies [

9,

10]. Where they recorded that all hospital surveyed in their study were having poor waste management in terms of regulation and concerning adequate ways to handle waste and even though waste disposal has not taken place due to lack of awareness by employees who tend to perform all related activities without proper safety, training, and direction. Therefore, the current research is timely in its quest to gain insights into the development of effective healthcare waste management practices by seeking to better understanding its antecedents and outcomes like organizational culture and environmental condition.

The authors [

11] mentioned that the main issues and challenges that affect healthcare waste management are organizational structure and infrastructure in the National Health Service (NHS) in Cornwall, UK. We note that their study did not concentrate on environmental factors that were highlighted in previous studies. Additionally, in their study, the waste manager and an administration assistant are responsible for observing the logistic documents along with other Cornwall Healthcare Estates and Support Services functions. This will result in inefficient communication to guarantee dissemination from trust management to all employees, which will also result in the manager having to communicate with each worker from all the trusts. A study of existing authors [

11] described the current waste management by Cornwall NHS from the perspective of organizational structure and barriers to recycling and reusable materials for the internal factors, whereas in this paper the conceptualization is forwarded to include more multidimensional factors and approach as presented in the later part of this study. Recently, the author [

12] examined the effect of education on compliance and waste generation in European healthcare. His findings illustrate low compliance and education is the greatest policy affecting compliance with proper healthcare waste handling. On the other hand, the author [

9] conducted a study in three different cities in Libya on the management of hospitals. Their findings show that the targeted hospitals transport their containers via uncovered trolleys. Containers are being dumped in total insanitary conditions and the final disposal practice of waste was discarded along with massive local waste in a bare state outside of city limits. The findings, in addition, revealed that 85% of the personnel surveyed (including managers, cleaning staff, and environmental workers) were not trained in hospital waste management. The situation in Libya is even worse. Data is not available on the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among handlers of healthcare waste [

10].

The purpose of this paper is to examine the influence of organizational factors and culture and structure on healthcare waste management practice in Libyan public hospitals. It ought to be noted that the present research is dissimilar from the study conducted by previous authors [

10] in two main parts: First, our sample covers a more extensive area, which includes five states in the southern region. Secondly, it focused only on internal factors (such as transport, onsite storage, segregation, and training).

The current study’s research gap is evident in its examination of the influence of organizational factors, namely, culture and structure, on healthcare waste management practices in Libyan hospitals. The findings can help hospital administrators and Libyan policymakers by providing insights into the effects of cultural factors on waste management practices and, as a result, finding ways to improve existing waste systems.

Thus, this paper is structured as follows. First, researchers begin by reviewing the empirical and theoretical background of organizational structure and culture as factors influencing healthcare waste management practice among Libyan hospitals. Next, the research hypotheses are developed. This is followed by the methods used in the study by shedding some light on the sampling technique used and research design. Before finally discussing implications and future research direction, the authors discuss important findings.

4. Results and Discussion

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to discover the underlying structure of the organizational structure and culture and healthcare waste management Practice measures. During the EFA, the 14 items of the OS construct were exposed to principal components analysis (PCA) using SPSS v20. To aid in the analysis of the two components of the construct, namely, centralization and formalization, Varimax rotation was carried out. The correlation matrix showed the items’ coefficients were at 0.3 or above. The scree plot showed an obvious break after the second component and the existence of two factors with robust loadings. The researcher then opted to retain two components for further investigation [

60]. This was strengthened by the parallel analysis showing the eigenvalue generated from EFA stopped exceeding the random criterion value created by parallel analysis at the third component (14 variables 171 respondents) (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3). Factor loadings were all acceptable for OS, OC, and HWMP ranging from 0.468 to 0.784, 0.433 to 0.749, and 0.523 to 0.793, respectively (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). To ensure the reliability of the scales, internal consistency confirmation of the scales was performed by checking the Cronbach ‘s alpha coefficient. The cut-off points for measuring the reliability for the current research is coefficient alpha of above 0.65 as recommended by the author [

55]. There was a total of two statistical measures to assess the factorability of the data conducted through Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) to determine the measure of sampling adequacy‖ value. The value reported was 0.887 for OC, 0.843 for OS, and 0.788 for HCWMP respectively, exceeding the recommended value of 0.6 [

61,

62,

63]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity [

64,

65] is significant at

p < 0.001. Therefore, the sample size here is adequate for factor analysis for all variables.

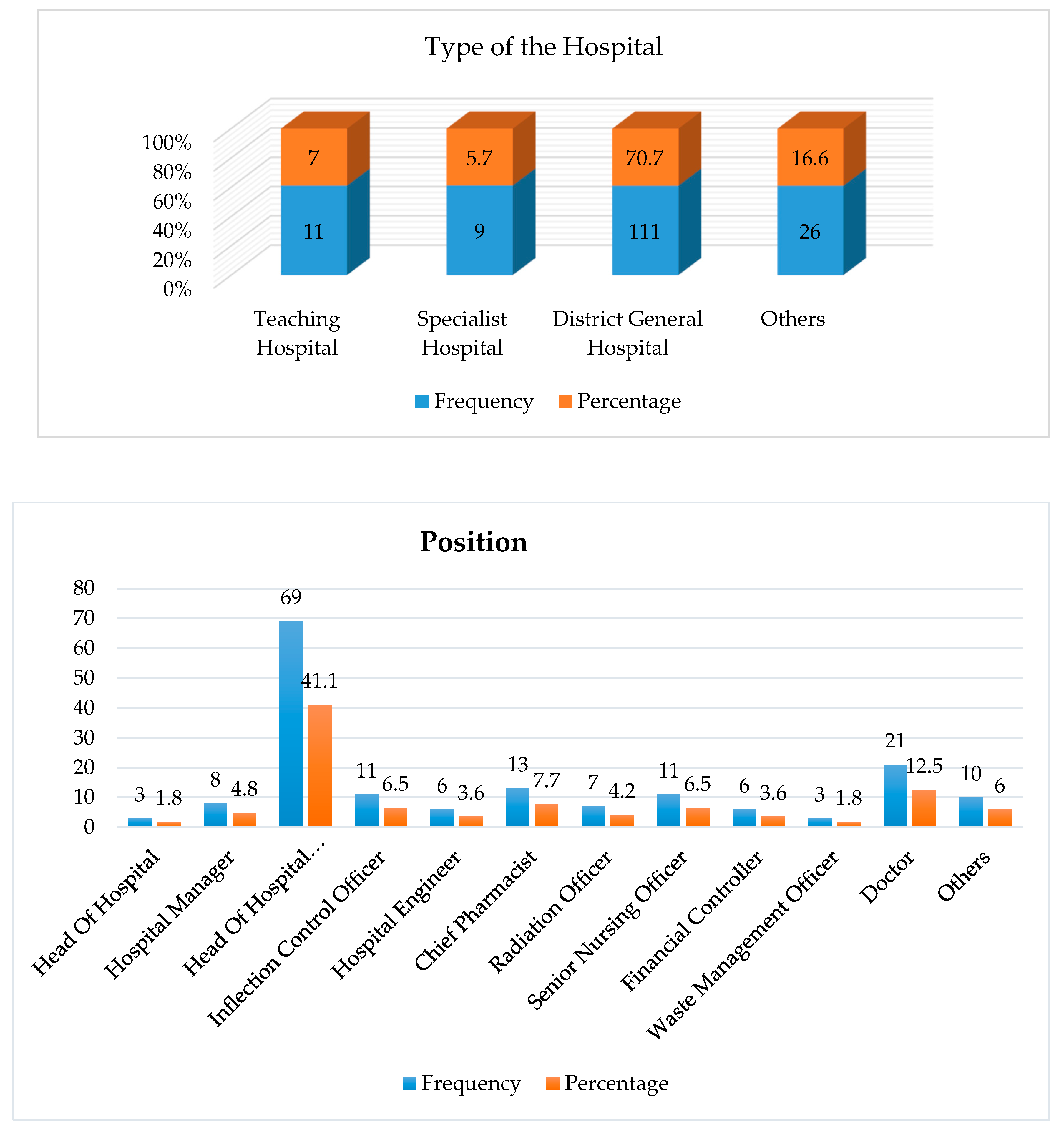

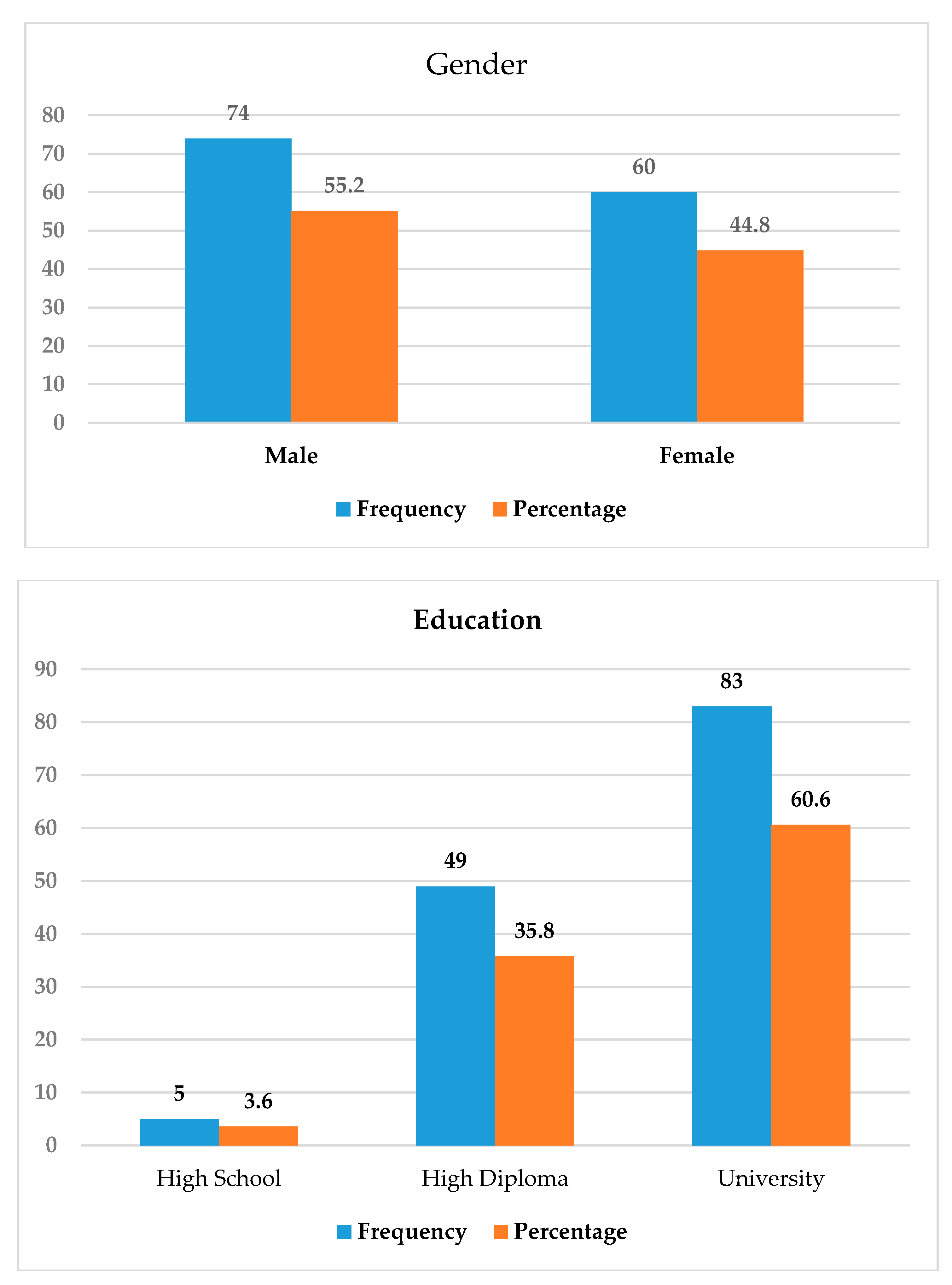

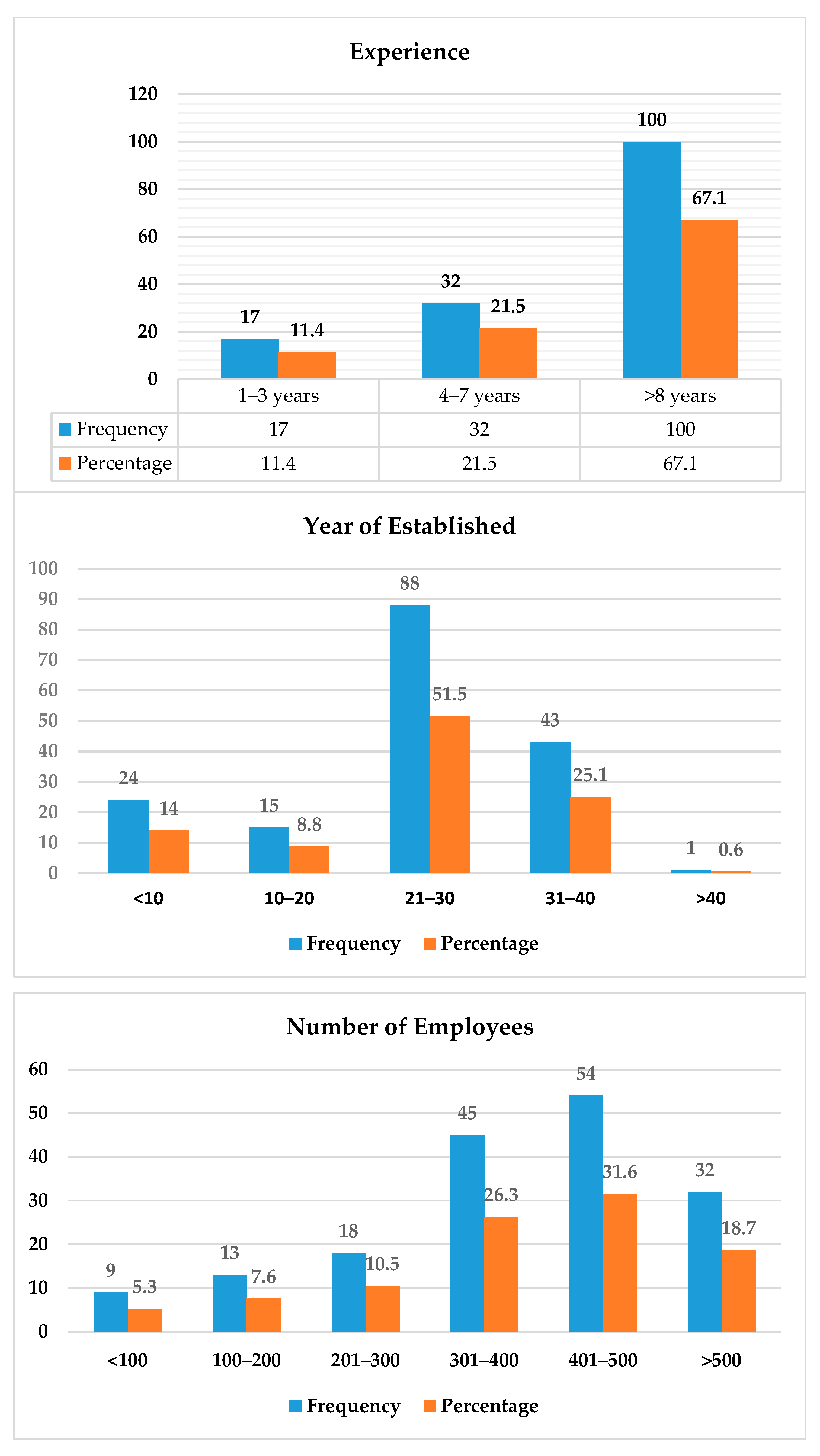

The charts in

Appendix A and

Table 4 show the demographic statistics of respondents’ background at the hospitals surveyed. Out of 171 respondents who returned the completed questionnaires, 70.7% of the participants were from the District General Hospital, while 7.0% came from teaching hospitals and 5.7% were from specialist hospitals. They held various positions in the hospital. Most of them were heads of departments (41.1%) and doctors (12.5%). Males made up 55.2 percent of respondents, while females made up 44.8 percent. Most of the participants had finished their tertiary education and had more than 8 years of experience. It could also be found that most of the hospitals were old hospitals, and they were established for more than 20 years. According to the number of employees, most of the participants were from the hospital with 300 employees.

Table 5 presents the correlation between medical waste management practices and structure. It was found that there was a significant relationship between both variables (r = 0.609,

p < 0.01). However, there was also an indication of the significant relationship between centralization and collection (r = 0.525,

p < 0.01) and disposal (r = 0.193,

p < 0.05). Another significant relationship can also be found between formalization collection (r = 0.486,

p < 0.01) and disposal (r = 0.208,

p < 0.01). Centralization and formalization were found to have no significant relationship with separation. The outcomes then provide the statistical proof to support H1 and H2.

Table 6 reveals that the OC-HWMP association was significant (r = 0.739,

p < 0.01). Another strong association appears between individualism and collection (r = 0.506,

p < 0.01) and disposal (r = 0.374,

p < 0.05) and between power distance collection (r = 0.282,

p < 0.01) and disposal (r = 0.436,

p < 0.01). The outcomes then provide the statistical evidence to support H

A1 (8), H

A1 (9).

Table 7 shows finding from the regression analysis which examined the OS-HWMP association. It was found that organizational structure explained 37.1 percent of MWMP (R

2 = 37.1, F = 49.03,

p < 0.01). Both dimensions significantly predicted the MWMP in public hospitals in Libya as follows: centralization (B = 0.313, t = 3.805,

p < 0.01) and formalization (B = 0.355, t = 4.316,

p < 0.01).

Likewise,

Table 8 showed the results of regression analysis that examined the OC-HWMP association. It was found that the organizational culture explained 57.8 percent of MWMP (R

2 = 0.578, F = 113.655,

p < 0.01). Both dimensions had also significantly predicted MWMP in public hospitals in Libya as follows: individualism and collectivism (B = 0.455, t = 7.508,

p < 0.01) and power distance (B = 0.388, t = 6.018,

p < 0.01).

The present study was conducted with two objectives in mind. First, it examined the relationship between organizational structure and organizational culture and healthcare waste management practice. In this study, organizational structure was conceptualized as formalization and centralization. Organizational culture was conceptualized as power distance and collectivism vs. individualism. Nevertheless, the output of factor analyses shows that segregation and collection disposal were highly correlated and were subsequently collapsed as a dimension of safe management practice of healthcare waste. The strong relationship between variables was addressed in the literature. The authors [

11] mention that the main challenges and issues, such as collection infrastructure, can affect waste management through the organizational structure of the National Health Service (NHS). Furthermore, the authors [

66] argued that the differences in medical waste management practice in terms of generation rate may be due to living habits, standards, availability of treatment facilities, and ways to categorize wastes. A study [

67] also reported that the medical waste generation rate depends on the size and the type of the medical institution and level of economic development. To have better practice of healthcare waste management, Libyan hospitals need to put into consideration employee training for old and new works, provide continuous education and have a management evaluation process for system and workers. Waste management practices were dimensional in this research: segregation, collection, and disposal. The importance of these processes is highly reported in literature. For example, to have a successful program with respect to HCWMP, a good plan must be available at the source of segregation, disinfection at the earliest opportunity, safe handling during transportation (within or outside the premises), and eco-friendly disposal [

68]. To have an effective medical waste management strategy, it is essential to understand current hospital practices concerning the segregation of a variety of waste category streams [

69]. In addition, the current study revealed that organizational culture has significant influence on HWMP in Libya. This might be due to the strength of relationship in which correlation coefficient between the two variables is (r = 739). The author [

70] states that when studying the situation in any advanced or less advanced country, it is essential to consider the cultural beliefs, degree of awareness of health issues, and the practices and technology during healthcare waste management. The entire process is conditioned by organizational culture because the values and behavioral norms held by organizational members serve as a filter in the sense-making and meaning-construction processes [

71].

5. Conclusions

The present research examined the relationships between organizational culture, structure, and healthcare waste management practice among Libyan public hospitals with the aim of assessing the relationships between organizational structure, culture, and healthcare waste management practice among Libyan public hospitals. The population for organizational study is southern Libyan public hospitals. Simple stratified random sampling was utilized for the hospitals selected. In addition, self-administrated structured questionnaires were physically distributed to 210 selected hospitals in the five states, followed by phone calls and reminders, seeking to get back positive feedback. A total of 171 respondents were returned. The data was also analyzed using a variety of methods, including correlation, regression, and descriptive analysis. The results of the reliability analysis showed that all the variables were reliable for this study by checking the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which held values greater than 0.65 for all variables. The regression analysis revealed that all the variables (organizational culture and structure) significantly predicted healthcare waste management practices in the Libyan hospitals. The results of the correlation analysis showed that organizational culture and organizational structure have a strong impact on HCWMP. The result of the descriptive analysis for the mean score ranged from 1.6 to 4.7, and all the standard deviations were low, except for Q6 about segregation of waste and Q14 about penalizing following Standard Operation Procedures (SOP) on healthcare waste, which suggested utilizing the data. In general, the current practice of healthcare waste management within Libyan hospitals indicates what has been previously stated: there was an emphasis on some of the major and priority needs in Libya’s primary healthcare structure and hospitals as per the authors [

2]. These include expanding sanitation standards and healthcare waste collection, disposal, training of selected staff, technical support for dumping significant amounts of expired drugs, creating medical waste separation, treatment, and disposal. In another study consistent with this research, conducted by the authors [

61,

62], it was determined that in most of the healthcare facilities surveyed in Turkey, top management, managers, and senior nurses did not pay any attention to hospital waste, due to their insufficient knowledge and the significance of medical waste and their lack of interest. However, in examining the extent of the relationship between organizational culture, structure, and healthcare waste management practice among Libyan public hospitals, in some recent and past studies, the focus was on type of healthcare facilities, thereby identifying health waste management practices from a one-dimensional approach, such as organizational structure [

11], organizational culture [

72], and organizational size [

73]. This one–dimensional concept may have brought about outcomes on the definition of healthcare waste management and research instruments that do not gather all the dimensions influencing the management of healthcare waste in the context of best practices. Therefore, this study empirically established the relationship between organizational structure, organizational culture, and healthcare waste management practice. Previous studies have shown that certain internal and external factors of organization do influence best practice of healthcare waste [

11,

66,

67]. This study will not be exhaustive enough without examining certain organizational internal factors that have been found to influence waste management as a best practice in previous studies. Therefore, there is a need to assess the extent of waste management from a multidimensional approach; this study seeks to fill the research gap created by scarcity of literature on healthcare waste management practice factors in Libyan industry. This study therefore aims at examining the influence of organizational structure and culture factors on healthcare waste management practices in southern public hospitals in Libya. Based on the results and the findings, this study succeeded in positioning the direct relationship between organizational internal factors of organizations and healthcare waste in Libya as far as the practice management is concerned. The method used in assessing the extent of healthcare waste management practice in this study can be useful in ranking Libyan public hospitals according to their level of waste management practice.

6. The Practical Implications of the Study

Practical implications of the current study are evident in that the findings can help improve the practice of healthcare waste management among Libyan hospitals. All the interested parties in the field of safe management of healthcare facilities, including managers, medical staff, nurses, environmental officers, and waste management officers, need to seriously give attention to factors such as organizational structure (centralization and formalization). For instance, previous studies [

63,

74] have illustrated that centralization may reduce the original solutions and impede communication between departments and the more regular sharing of information and ideas because of the existence of time-consuming formal communication channels.

This may clearly be noticed when a healthcare facility has accumulated expired medications that must be handled. In a similar vein with formalization, healthcare waste management with proper structure and clear rules and procedures will allow the management to easily handle the waste properly where it is generated from different departments, and secondly, it will decrease ambiguity [

34,

75]. Lastly, with formal procedures, employees tend to handle situations more effectively because they comprise best practices learnt from experience and which are fused into organizational memory [

35]. Furthermore, this research plays an essential role that is important to whoever oversees medical waste management, such as the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Environment, healthcare facilities’ managers, and the lower-level staff.

To summarize, in gathering all the relevant information for this research, there are limitations that arise from using single respondents to collect data and employing the survey method. Thus, our future directions in this field of research should consider multiple respondents for gathering the relevant data. Additionally, moderating variables can be examined to increase our understanding of the relationships studied, like hospital location and type of services offered, and the relationships between organizational factors and medical waste management practices.