3. Results

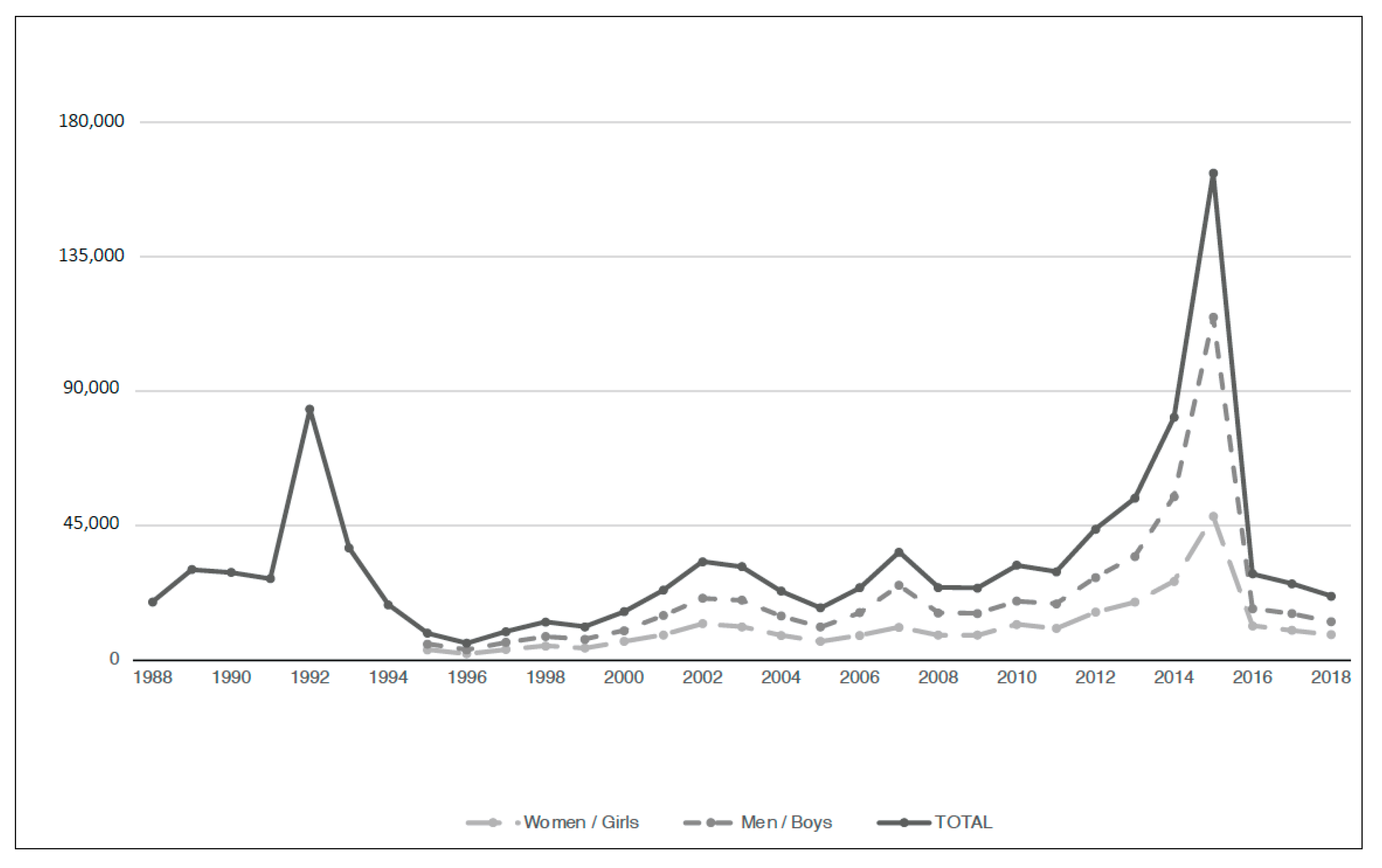

The true impact of displacement cannot be measured or studied by only focusing on direct costs or consequences. Zetter and Pearl (2000) [

22] argue that it is important to take overall costs and benefits of all interest groups, such as displaced populations, host communities, governments, donors, and agencies. In the REGARD project as a whole, and particularly in the Swedish case, the impact of relocation and effect on social cohesion was studied through examining the needs of both new arrivals and the host communities in the critical sectors that form the built environment as framed by the above noted conceptual framework.

The needs assessment was first carried out through a literature review followed by in-depth and validation interviews as referred to above. While all the sectors were touched upon and covered in the actual data collection (housing, socio-cultural, education, health, economic, physical infrastructure, governance, and communities with special needs), only the first five sectors will form the focus of this paper in the Sweden case with special reference to women and children’s needs as they appeared to be critical and of higher profile during the interviews.

3.1. Housing Needs

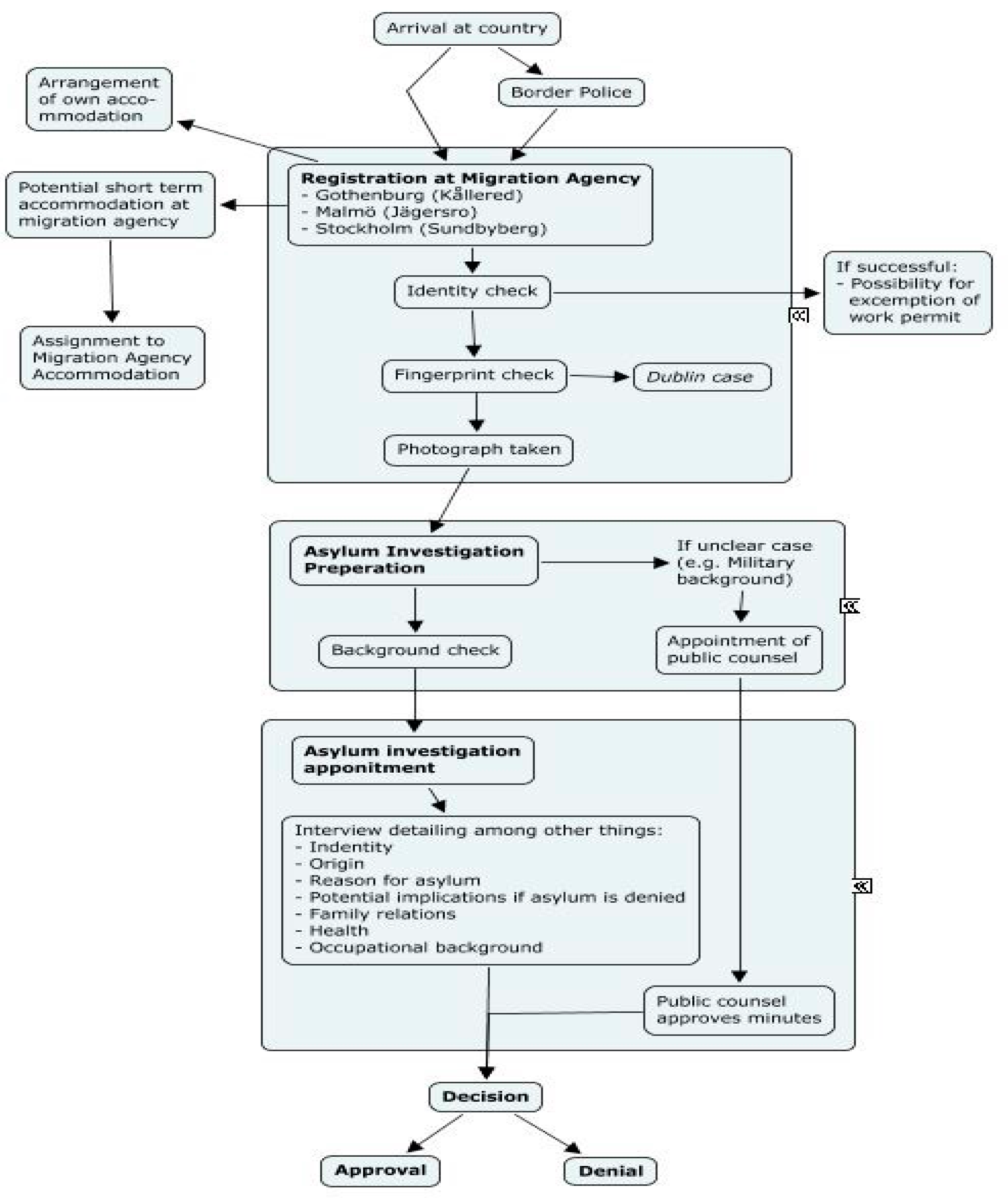

In Sweden, upon asylum registration the Swedish Migration Agency (

Migrationsverket) inquires if the applicant requires housing or will provide housing on his/her own. Accommodation provided by the Migration Agency is on a no-choice basis. The asylum seeker might be moved from one facility to the other during the period his/her asylum application is being processed because there is fluctuation in the Migration Agency’s housing facilities [

6]. Housing provided by the Migration Agency tends to be located in smaller municipalities or on the outskirts of larger ones; however, this varies greatly across the country.

Asylum seekers who provide their own housing rely largely on family and friends for finding housing and this is much more common in densely populated areas such as Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö [

23]. Those who wanted to seek asylum in Sweden were provided initial temporary housing (

ankomstboende) by

Migrationsverket before moving on to special asylum seeker housing arrangements (

asylboende). Those who are not sure whether they wanted to seek asylum in Sweden are left to the mercy of NGOs who provide them with emergency housing. Churches, mosques, hostels, and some private individuals help in finding housing for the arriving asylum seekers. In other words, civil society plays a great role in making sure arriving asylum seekers are provided a place to stay.

Within two months of an asylum application approval, asylum seekers who previously were housed by the Swedish Migration Agency are allocated to a Swedish municipality, which is to provide housing for the now refugee according to the Swedish Code of Statutes (2016:38), also known as

Bosättningslagen. Which municipality the refugee is allocated to is determined, among other things, based on the municipality’s size, the local labor market situation, and the number of refugees and newly arrived already living in the municipality, in combination with the specific needs of the refugee. These factors are taken into account by

Migrationsverket when it decides how big a portion of the refugees accepted by Sweden every municipality should receive (Municipalities Interviews). As such, the newly arrived resident normally has little say in where he or she will be settling [

24,

25].

The portion of refugees which are provided housing via municipality arrangements vis-a-vis those responsible for finding their own housing reportedly varies significantly from municipality to municipality. Some municipalities reported that almost every refugee arriving was finding housing on his/her own, whereas other municipalities described almost the opposite situation.

One of the advantages of Bosättningslagen is that it helps municipalities prepare for the reception of refugees, and that it hence may facilitate integration. Adequate information, time to prepare, and working along long-term perspectives were mentioned by many interviewees as key for successful integration, especially in the initial reception of refugees to the municipalities.

Among the advantages of providing one’s own housing is that the refugees get to decide on their own where they wish to live, which means that they may stay near family and friends, and that managing to find housing on one’s own provides a sense of agency and pride in being able to provide for oneself. Staying near family and friends was stressed as an important factor for successful integration by one municipality representative, as this creates a sense of safety and solidarity. However, this also leads to segregation as most refugees choose or, for economic reasons, are forced to choose housing in certain districts, resulting in cases of illegal contracts, third hand contracts, overcrowding of apartments, and non-favorable lodging agreements (inneboende in Swedish).

An increasingly prominent issue is the group of individuals who have managed to establish themselves in Sweden, but whose initial housing provisions were ending (NGOs Interviews). As housing queues are often long, these individuals and their families were not able to find housing easily, and had to look for housing outside of the big cities, away from their newly established social networks. This risk contributes to social alienation and isolation, especially as many refugees are relying on public transport as their main mode of accessing the city. Overall, temporality of housing arrangements was mentioned both by municipality and NGO representatives as an issue causing uncertainty, and as a potential contributor to mental health issues—a specific issue that will be further elaborated on in the paper.

3.2. Socio-Cultural Needs

In the reviewed literature, newly arrived residents interviewed indicated that they wish to be socially integrated into society, motivating the need for social integration by understanding the new society, learning about Swedish culture and rules, making friends, and obtaining a general sense of wellbeing. However, the same interviews also pointed out that many refugees may feel that they are “stuck” between their own and the host community’s culture, which points to the fact that as well as being keen on adapting to and learning how to function in a new society and culture, they still have specific needs that may need to be catered for.

One of the expressed difficulties is in connecting with Swedes and the perception that Swedes are comparably introverted and difficult to connect with [

7] (pp. 27–28). Consequently, there is a great need for meeting points facilitating cultural exchanges, a need which is hard to cater for. Both the creation of such meeting points and encouraging everyone including established Swedes in society to participate were mentioned by one NGO interviewee as crucial for integration. Refugees need the right conditions to understand Swedish society, as it may be hard to penetrate or understand from the outside when Swedes, in general, are not always good at explaining social codes. These meeting points need to be more natural than what is currently the case, and here civil society again may play a great role.

Finding and building relevant social networks of all kinds by refugees is the most prominent need mentioned both by municipality and NGO interviewees, on the REGARD project needs assessment, as they are essential for integration and many, especially the quota refugees, arrive without access to these and many other resources, thereby having a weaker social security network. A great help to overcome the issues mentioned above is to have family and friends nearby as a source of comfort, but also a place of refuge from which exploration towards integration can be safely pursued [

7] (p. 65). A lack of nearby family is, therefore, a barrier to integration, as several asylum seekers and newly arrived residents speak of the difficulties in concentrating on studies, education, and future work when their loved ones are stuck in refugee camps, have disappeared because of war, or internal conflict is ongoing back home where family and friends live [

26] (p. 21), [

7] (pp. 6,21–23,32).

3.3. Education Needs

The SFI (

Svenska för Invandrare) is a national language teaching program funded and implemented by the local municipality. For this reason, SFI drastically differs geographically when it comes to the number of students and funding. The municipalities’ priorities differ much when it comes to SFI, which in turn is likely to influence the quality of the education [

27]. Again, refugees’ opportunities for integration into Swedish society are dependent on the specific focus, resources, and policies of the single municipality, and how consequently the opportunities for integration may differ greatly depending on where in Sweden the refugee is placed, how quickly they have access to a place on the SFI courses, number of students in the class, etc.

The educational needs of refugees also vary greatly, as groups arriving include everything from quota refugees to highly educated refugees. With differing needs and a wide range of levels of educational among refugees, there exactly lies the greatest challenge for many municipalities—to cater for a group whose needs vary greatly, when resources and opportunities may be restricted. For highly skilled or educated refugees, a prominent barrier to accessing the Swedish education system is proper documentation or certification of skills and education. However, for lowly educated or semi-skilled refugees, there is an overall need for vocational training, on a high school level (yrkesgymnasium) with language support in particular.

The most prominent problem mentioned by both municipality and NGO interviewees with reference to education, and in particular with reference to language education, was how the Swedish society and system were simply not adapted to illiterates (Municipalities Interview). Many interviewees in the course of the REGARD Project mentioned that they believed that for some groups the Swedish education requirements are far too high, and that extra education or language are not necessary for all groups.

The case of illiterates illustrates how hard it is for un-skilled or low-skilled and educated individuals to manage the Swedish system on the whole. One interviewee stressed the importance of creating good conditions for low-skilled workers or low educated people, in order for them to grow as human beings and be able to provide for themselves (Ibid). Part of this work might consist of lowering the language and other requirements of many jobs, which many municipality interviewees deemed were unnecessarily high or bureaucratic and made it difficult for many job seeking refugees to find work.

3.4. Health and Well-Being Needs

Mental health issues such as depression, PTSD, difficulties concentrating, and more were by far the most prominent health issues mentioned during interviews. Refugees being burdened by traumatic experiences is not unique to Sweden, but [

28] points out that traumatic experiences make refugees more vulnerable in stressed situations, which increases a feeling of helplessness and anxiety, which in turn can influence integration [

28] cited in [

7] (p. 6). This conclusion is supported by another study, which found that “the migration process and the environment in the new country contributed to the increased risk of developing mental illness”. The same study pointed to the lack of control of their lives, long asylum process, and self-isolation due to language barriers, culture, and discrimination as likely causes [

29] (pp. 13–15). Findings from the interviews in the REGARD project are in line with these conclusions. In addition, it was mentioned that cultural differences may be an issue, as many refugees may not be willing or know how to talk about their mental health problems. Practical difficulties such as long waiting times, access to mental health professionals able to cater for refugees’ specific issues, and access to interpreters were also mentioned as common issues, and psychological care for unaccompanied minors was pointed out as a particularly urgent problem.

Moreover, during the asylum process and the establishment process, the asylum seeker or newly arrived resident is forced to relive trauma through the repeated telling of their story to various administrators. This issue is increased as administrators can change during the process and the story has to be retold, increasing the risk of mental health issues [

7]. Women were mentioned as often being forgotten when talking about the health of the family. They were mentioned as being more alienated than men. Violence in families may be a problem, and here refugee women may be particularly vulnerable because of their weaker social networks.

3.5. Economic Needs

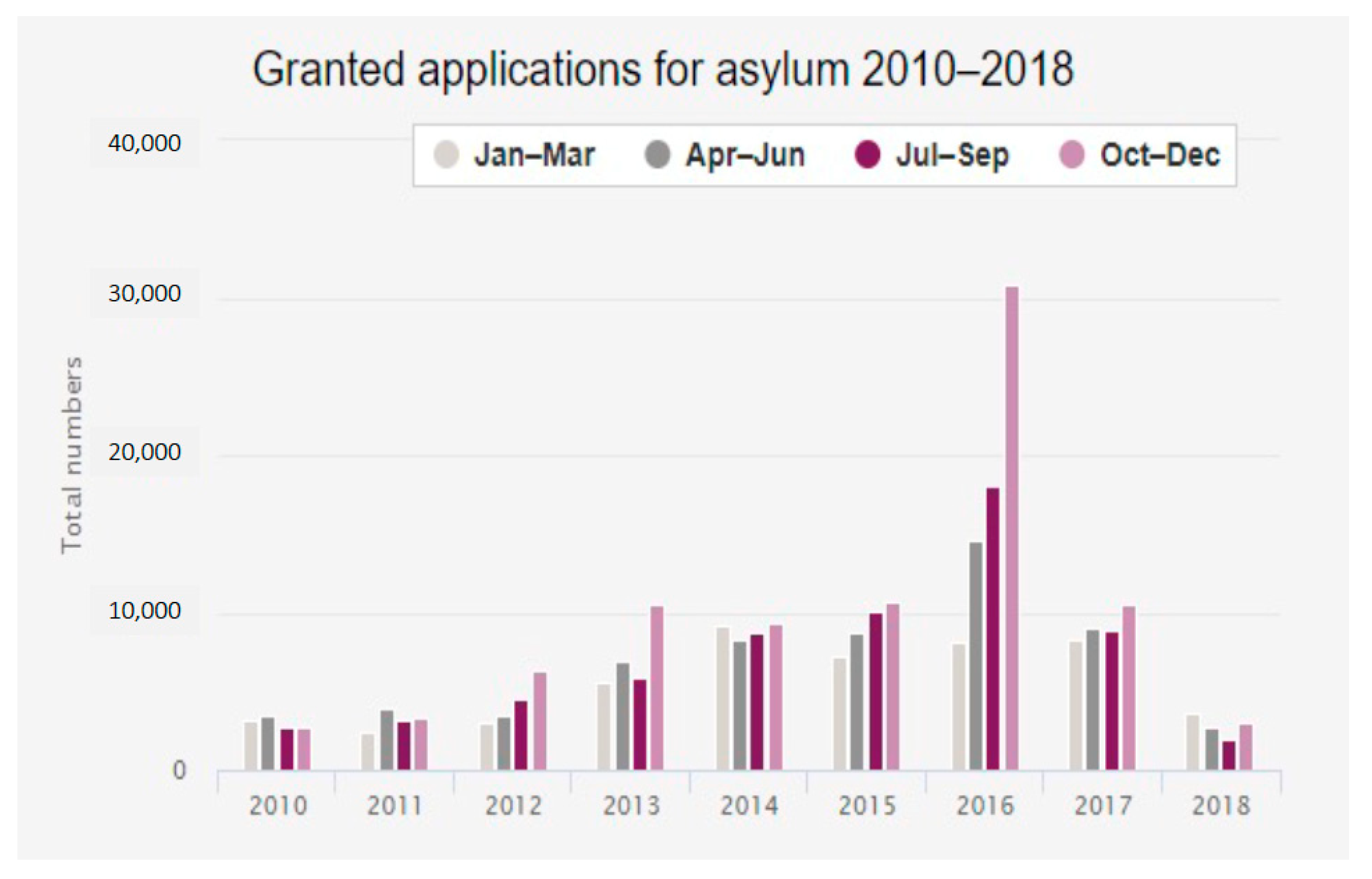

While an asylum application is being processed, an asylum seeker might be allowed to work given that certain conditions are met. These conditions pertain to the degree of certainty according to which the asylum seeker’s identity can be ascertained. While the Swedish Migration Agency issues the work permits, it does not know how many of the asylum seekers actively work (P. Engman, personal communication, 11 April 2019) (Statistician, Swedish Migration Agency), as many refugees may receive work via personal contacts or the like. Once a refugee has gotten his/her asylum application approved, he/she may choose to be enrolled in an establishment program (Etableringsprogrammet) led by the Swedish Public Employment Service (Arbetsförmedlingen). The goal of the program is for the refugee to, as quickly as possible, learn Swedish, find a job, and be able to manage his/her own livelihood. Within Etableringsprogrammet, the resident combines language studies at SFI with job seeking efforts such as internships, courses, and similar [

30].

However, the Swedish Public Employment Service has limited possibilities for education and other activities. As such, the staff of the Swedish Public Employment Service appear to be generally concerned with the family situation, and the refugees’ educational and vocational background appears to matter less. The result is that some newly arrived residents feel pressured to seek jobs they lack experience in or do not want [

26] (p. 5). Some newly arrived residents, especially those with a high educational or vocational background, had difficulties adjusting to the long path in order to receive a comparable position [

7] (p. 25). Certain “quick tracks” (Snabbspår, for instance it is possible to go through the SFI program quicker than what is normally the case) are in place for academics with specific backgrounds, such as doctors where the demand from the labor market is greater [

31].

4. Discussion

This section will reflect on the issues identified in the needs assessment research phase and elaborate on the nuances and root causes of challenges facing refugees and asylum seekers, as well as the host community including government structures in resettlement and social integration.

The starting point in further understanding housing needs challenges is further analysis of the

Bosättningslagen. Bosättningslagen stipulates that all municipalities are obliged to receive refugees whose asylum applications have been approved, if they are allocated to the municipality by the Migration Agency. While the law does not give any indication as to the amount of time municipalities have to provide refugees with housing when they arrive, several municipalities interpreted that the provision of accommodation should last for two years, due to the possibility of receiving government grants during the first two years. Other municipalities use the average apartment queue length as their guide, while yet others strive for permanent solutions, albeit sometimes in the form of older apartments [

24]. The average time that newly arrived refugees can rely on the municipality for housing thus varies from municipality to municipality and significantly affects their experience with resettlement and integration.

The room for interpretation that exists in Bosättningslagen was problematized by several municipality interviewees (Municipalities Interview Summary). Negative implications include that the reception and support that refugees receive varies, depending on the resources available and the general focus of the municipality. This means that refugees may not be treated equally or be offered equal opportunities depending on where in Sweden they are placed. The above also means that whether the needs of refugees are met or not is not so much dependent on the actual strategies or laws of the Swedish government, but more on how municipalities choose to interpret these strategies and what resources they have at hand. Consequently, integration of refugees is largely managed on a municipality level, or at least is directly affected by municipality policies to a greater extent than the policies of the Swedish state, resulting in what is euphemistically termed a ‘postcode lottery’ for the refugees and asylum seekers.

Municipality interviewees stressed how “government strategies actually are not taking into account the specific needs of the municipalities” (Ibid). For instance, one interviewee mentioned how the Migration Agency does not take the host municipality into account in the planning of its asylum centers (asylboende). It was mentioned that for the establishment of such centers, the Migration Agency enters into contracts with private players without communicating with the municipality as such. Placement of asylum reception centers and the inflow of new inhabitants that comes with them disturb the municipality’s welfare system, which Migrationsverket, according to the same interviewee, does not take into account.

Another structural issue that affects the housing situation of refugees and newly arrived in Sweden was mentioned by municipal interviewees, and is two-fold (Ibid). First, it involves the diversity of statuses or types of residence permits that refugees receive. This differs because not everybody has the right to the same help and support, which poses problems both as refugees are treated unequally, and as some refugees may think they are entitled to services they are not entitled to. Second, housing providers (landlords) require tenants to have stable and regular income, a requirement which few refugees fulfil. This is an issue both for those refugees taking part in the Etableringsprogrammet, and those who do not. The money received when taking part in the Etableringsprogrammet counts as stable income by housing providers, but as Etableringsprogrammet lasts only two years, and many refugees may have to spend the first year of their stay queuing for housing, this means that when they have gotten enough points to access housing, they often will have only one year or less left of Etableringsprogrammet (and hence only one year left of stable income, which many housing providers deem not secure enough).

Alleviating housing needs difficulties are measures aiming at creating greater awareness among landlords and social housing authorities about the limitations for refugees to meet standard housing requirements [

32]. Training of housing providers on the specificities of refugees’ housing needs is a factor in improving refugees’ access to suitable housing, in combination with providing information to refugees themselves on housing options and housing markets [

33]. Successful housing projects do not further reinforce social isolation of marginalized communities, but reduce or eliminate both physical isolation and improve access to basic services for refugees.

The need for taking individuals’ backgrounds, motivations, and aspirations into consideration prevails also with regard to meeting their socio-cultural needs. This becomes particularly evident when discussing language education, especially as refugees’ varying backgrounds with regard to language and other education have presented themselves as major obstacles to designing effective integration measures. The more integration measures take the specific characteristics of individuals’ skillsets into account, while matching such initiatives with the needs of the host community, the more effective they are in the long-term.

Language training needs to be adapted to the various stages of the integration process [

34], in terms of how higher language training is made available targeting highly skilled refugees [

32,

35] and providing informal learning opportunities for those with limited educational backgrounds [

33], but also in terms of language education targeted to specific occupations or sectors in order to provide participants with relevant and work specific vocabulary and ensure that they are ready for the labor market.

The findings from [

26] are supported by [

7], who found that many newly arrived residents have the stance that language is the path to a job, rather than having a job being key to the language. Furthermore, [

7] (p. 22) express that “[their] results indicate a paradoxical connection where the hunt for work can risk education and thus development of language”. Similar to the government’s stance, newly arrived residents see job acquisition as vital for integration. Those with a high vocational or academic educational background see the job as a goal in itself, whereas for refugees with lower vocational or academic background it is more the ability to be self-reliant and the way in which the job integrates a person into society that is of importance. The former group tends to act more independently in their job seeking, while the latter is more dependent on council from friends and family or authority/NGO [

7] (pp. 20–22).

Much of refugees’ needs related to culture lie in understanding and adapting to a new cultural context once arriving in their host community. Bettering of both refugees’ understanding of the host community’s culture, and vice versa, may take place both before and after the refugees have arrived in their destination community [

36]. Equally, the focus needs to be on integration as a two-way process and on mutual efforts to reach understanding, and not solely the absorption of one culture by the other. Both guest and host community need to work together to solve integration challenges, with the benefit that each becomes accustomed to the other’s culture.

Inclusive integration process characterized by equality requires the involvement of a multitude of stakeholders in society, and not simply the refugees themselves or those who are directly involved in the design and execution of integration measures [

35,

37,

38,

39]. Several sources [

32,

40,

41,

42] specifically mention the use of mentorships and volunteer interaction to support the creation of meaningful social networking. Such mentorships and social networks are seen as helping refugees in the process of making friends, navigating their new community, and overcoming cultural barriers between their own and the host community.

Another important prerequisite for promoting fairness and equality is instating strong anti-discrimination frameworks and the promotion of intercultural dialogue [

32,

36,

41]. Measures for facilitating intercultural dialogue are, for instance, ensuring that the professionals involved in the integration process, such as social workers, should be highly culturally competent and possess both cultural sensitivity towards the individuals they meet and a political awareness of the bigger situation they are dealing with (e.g., the background of the conflict that led to the displacement, a fair degree of historical and political knowledge of the area the displacees come from, and a general cultural understanding of their society) [

43,

44].

When it comes to health and well-being, the most prominent factor mentioned is to consider health as a “cross-cutting issue affecting many aspects of the integration process” [

32], and “recognizing that all factors play an important role in affecting refugees’ health” [

44]. In other terms, successful approaches to refugees’ health and wellbeing look upon health from a holistic perspective, not treating it in isolation from other aspects of refugees’ lives. Successful approaches do not only look upon the systematic treatment of diseases or cases as such, but also take into account cultural and social factors such as community needs assessments, education, or assessments of beliefs and expectations.

This is no clearer than when looking at the intricate and complex connections between children and women’s education and health needs and their overall integration in a new society.

Women were portrayed as at risk of being alienated and isolated, due to factors such as maternity leave, weaker social networks, and hardships regarding entering the labor market. Women may be extra exposed both physically and mentally when they are supposed to be integrated into a new culture where society lays a lot of demands on them, in addition to the already existing demands from family and relatives. Violence within the family is also a concern, as many women do not have social networks in place to support them. Women with young children are particularly vulnerable and in need of extra language and parental support, as well as help in creating social networks. All these factors come together to determine an individual’s experience and what forms of support they need to be offered and at what stage in their life.

Children, on the other hand, face challenges when it comes to education due to language barriers, incorrect placement, and lack of support from home. These challenges cause several children to drop out of school before achieving their post-secondary education [

45] (p. 2). As children have the right to attend school and learn Swedish at an earlier stage in their asylum application process, they also often serve as translators for their families and have to take responsibility for their parents’ integration process if they arrived with their parents or after family reunification, which causes further complications as will be highlighted below.

A study regarding children and the Swedish asylum reception structure highlights findings that, in the political discourse, asylum seeking unaccompanied children are talked about differently than adult asylum seekers, with a focus on their vulnerability resulting in their right of residence being motivated by compassion rather than a right to asylum as political subjects [

46] (p. 34). What is critical is that unaccompanied children make up a greater portion compared to the whole child population when it comes to psychiatric problems, with 3.4 percent compared to 0.26 percent [

46]. Another study further confirms that the migration process and the environment in the new country contributed to the increased risk of developing mental illness. The study pointed at the lack of control of their lives, long asylum processes, and self-isolation caused by language barriers and discrimination as likely causes [

29] (pp. 13–15).

Interviews with children in Sweden pointed out three important factors for their wellbeing: the presence of parents; going to school; and having social contacts in their spare time [

47] cited in [

46] (p. 35). The presence of parents is an apparent issue for unaccompanied children. In Sweden, each refugee child who has been granted right of residence has the right of reunification with their parents. While this is generally a good thing, as indicated above, some of the children interviewed by [

45] indicated that the reunification brought with it problems as the children had become independent and used to a degree of freedom where they can decide much on their own. Upon reunification, several challenges appear as the child must readjust to having a guardian and losing some of their independence. In addition, the children, having obtained a knowledge of the Swedish language and the Swedish system, were obliged to take responsibility of their parents’ integration process, resulting in, among other things, missing school days as well as an almost role reversal and parents’ overdependence on their children [

45] (pp. 30–33).

As further evidence of the interconnectedness of integration factors across sectors and services, the REGARD project found that three discourses dominate the literature on what constitutes good practice in relation to education of children and young individuals, namely: the importance of a welcoming environment free of racism; the need to meet psycho-social needs, particularly if there are prior experiences of trauma; and linguistic needs [

48]. Apart from promoting a commitment to social justice, an inclusive approach, and supporting the learning needs of students, successful integration measures within this sector have involved recognizing the complexity of needs of asylum seeker and refugee children, and the importance of parental involvement, community links, and working with other agencies [

48].

When it comes to economic needs, access to the labor market and employment, historically, the focus on work versus education has depended greatly on the conditions of the Swedish labor market. During periods of high demand from the labor market, migrants could move directly into the labor force, even with little or no knowledge of Swedish. Conversely, during periods of low demand, government efforts always aimed at making the migrant more appealing and employable in the future, focusing on education. These trends have been observed both nationally and on a local scale [

26] (pp. 32–33).

The strongest barriers portrayed were an unnecessarily bureaucratic Swedish system, unrealistic requirements for low skilled jobs, and a general lack of jobs for refugees with little or no educational background. Sweden is at large a rather bureaucratic country, and the Swedish reception system is perceived as complex and difficult to navigate for many asylum seekers and newly arrived residents, especially if these come from a lower educational background [

7] (pp. 21,23). This “square” bureaucracy, or treatment by officials, is seen as a barrier to integration and newly arrived residents and asylum seekers often express that informal paths, such as personal contacts and meetings, are more functional for gaining an understanding of the system [

7] (pp. 6–7).

The effective determination and measuring of refugees’ previous qualifications, skills, and education have been pointed out as barriers to prompt and effective integration, which further makes the individualization of the integration process more difficult. Examples from other countries abound, one of which quoted by interviewees is the flexible approach endorsed by Hungary, where there are two possibilities for recognition of documents and qualifications: one is represented by the official path and getting recognition by the Hungarian Equivalence and Information Centre, whereas the other possibility is represented by a more flexible approach involving the chosen institution [

49]. Another example of alternative ways of assessing refugees’ previous competencies is the

Jobprofil competency assessment in Austria, where initial assessment is followed by an interview and the results are made available to the Public Employment Service in order to facilitate employment [

33].

Many interviewees did not perceive that the Swedish government has any explicit strategies in place to cater for the needs of refugees, or at least did not know whether any such strategies exist. The two strategies most prominently mentioned were Bosättningslagen and Etableringsprogrammet, both of which have been discussed in detail above. Most interviewees were also unsure as to whether these strategies were implemented as was intended (Municipalities Interview).

Where the system seems to work at cross purposes or ignore contextual realities, is with many low qualified professions (e.g., cleaning or hotel personnel) where there is great need for human power. Many refugees are willing to work and to fill these positions, but cannot do so because of extensive Swedish regulations and overambitious requirements with regards to language and other skills. Most employers require at least high school education, even for the simplest of tasks. Private companies may be in need of employees but require proper documentation and moreover often Swedish education, which further adds to the difficulties for many refugees to find work.

Measures promoting the employment of refugees not only refer to facilitating access to education and the effective determination of previous qualifications, but also the importance of addressing the employers themselves. This aspect is two-fold. First, promoting refugees as a talented and useful workforce to employers, as well as promoting the acceptance for and understanding of foreign education [

34,

39]. This is important for working against the stigma of employing refugees that still prevails in certain contexts. Second, the importance of involving employers themselves in the design of measures aimed at facilitating refugees’ introduction into the labor market, while allowing employers to have an active role in designing policies and programs will ensure that these policies and programs would meet the demand and needs, and be attractive to other local employers [

41].

Other measures facilitating introduction into the labor market are providing possibilities for combining work (e.g., in the form of volunteering, internships, work experience, or apprenticeships) with language education, tailored mentoring, or initiatives which involve training in combination with employer placements [

32,

33,

41]. It has been pointed out that both the location in which refugees are resettled and the quickness of the initial access to the labor market affect refugees’ labor market introduction [

33]. It may therefore be beneficial to match refugees with the most appropriate dispersal location based on factors including their education levels and work experience, as well as promote fast decisions on asylum cases in order to shorten the time before refugees’ access the host community labor market.

5. Conclusions

The literature review and the results and discussion above of the Sweden case point to four cross-cutting factors as especially important in the striving for successful integration, namely: the individuality of the integration process; seeing integration as a two-way effort; increasing efforts to collect data in relation to integration matters; and putting integration initiatives in a long-term perspective. These four factors do not present themselves as sector specific but should rather be viewed as underlying prerequisites and conditions for integration initiatives to be able to strive for sustainability and efficiency, regardless of whether these measures are aimed at displacees’ introduction into the labor market, at acquiring language skills, education or training, at tackling health issues, or at other integration related areas.

First, the individuality of each displacee or refugee is central to a meaningful integration. For that process to take place the stress needs to be on the importance of client-centered and strength-based practices where personal motivation is allowed to take a central place in the services provided aiming at resettlement and integration [

32,

37]. The focus on individualized integration efforts is coupled with an emphasis on the importance of refugees’ involvement themselves in the design of the integration process, for the above mentioned individualization to materialize [

36].

Second, integration as a two-way process means the necessary involvement of both host and guest community, and to not simply regard this process as the absorption or assimilation of one community into the other [

32,

33,

35,

36,

39,

41]. Both host and guest community have to be equally involved and make a mutual effort to adapt to a situation which is novel to both, working around an idea of integration based on social cohesion and inclusion. One study emphasizes how “supporting the wider participation of refugees in society implies a process of mutual acceptance and adaption of cultural features that are exchanged on the basis of equality” [

35]. Integration needs to be seen as “a process that involves an entire community, not just its most recent members” [

41], and one in which the entirety of society needs to respond in order to bring about systemic change and adapt to both the needs of refugees and host community.

Third, displacement of populations puts both host and guest community into pressured and often highly politicized situations which require quick solutions. However, integration processes are lengthy and complicated, and are not always best addressed by short-term initiatives. Interviewees, especially in Sweden, described many of the current integration efforts carried out as “putting out fires” instead of aiming for growth and sustainability. Moreover, integration projects “need time to establish, build trust and create networks between refugees and local organizations and agencies”, all of which take time [

33].

Fourth, many of the implications of mass population displacement are yet to be known and still require further research, especially in the light of recent migration movements during 2015 and 2016, and at the time of writing the unfolding situation in Afghanistan and its anticipated consequences. Research on integration is therefore encouraged within all policy areas [

32], as well as putting in place adequate instruments for collection of both qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data are stressed as an important complement to the measuring of integration in terms of numbers and statistics. In other words, “targeted longitudinal qualitative research will also be useful to better understand refugee integration in all policy areas and to understand the nuances that statistical data cannot reveal” [

32].

While the Swedish case is considered a model one in Europe by comparison, several municipality and NGO interviewees stressed the importance of cooperation and coordination between various actors and levels in order to address some of the shortcomings outlined above. This referred both to better cooperation and coordination between municipality and government functions, as well as better cooperation between municipalities and civil society. One good practice example of working strategically, while at the same time promoting this type of coordination and cooperation between local and national entities, involves setting up a Refugee Taskforce, involving city services, social welfare, local NGOs, and independent volunteers, all coordinated by the local authorities. The purpose of such a Taskforce is to ensure cooperation between refugee shelters to promote the exchange of good practice, ensure appropriate information exchange with citizens, and bring in civil society, while simultaneously facilitating asylum seekers’ access to relevant organizations as early on in the integration process as possible.

To be more specific, for example promoting cultural competency, for effective promotion of equality, fairness, and social inclusion to take place suggests a change in the discourse as to how refugees are treated. One source suggests that problems experienced by refugees should perhaps be better seen as “problems of exclusion” rather than “problems particularly experienced by migrants”, as they are commonly phrased [

40]. Similarly, another source criticizes the Swedish language education system put in place for refugees as “problematizing migrants”, given the extensive state sponsored language training provided, while what might be necessary is a problematization of the host community via strengthening of anti-discrimination measures and equal opportunities training for the host citizens [

50].

Adequate policies should take into account and include all aspects of life, and not only focus on isolated areas of refugees’ lives, such as labor market introduction. In certain contexts, the question of how to introduce refugees to the labor market may prevail. To counter this, one study suggests a shift in focus of the strategic work with integration issues, where establishment in the labor market should be seen as more of a long-term goal rather than the primary aim of integration [

39]. Individual targeted and focused initiatives should adopt a holistic perspective which places the individual in a bigger context and takes into account various types of participation in society. Taken all together this may create a sense of belonging and contribute to more sustainable integration [

39].