Abstract

Medium-term electricity consumption and load forecasting in smart grids is an attractive topic of study, especially using innovative data analysis approaches for future energy consumption trends. Loss of electricity during generation and use is also a problem to be addressed. Both consumers and utilities can benefit from a predictive study of electricity demand and pricing. In this study, we used a new machine learning approach called AdaBoost to identify key features from an ISO-NE dataset that includes daily consumption data over eight years. Moreover, the DT classifier and RF are widely used to extract the best features from the dataset. Moreover, we predicted the electricity load and price using machine learning techniques including support vector machine (SVM) and deep learning techniques such as a convolutional neural network (CNN). Coronavirus herd immunity optimization (CHIO), a novel optimization approach, was used to modify the hyperparameters to increase efficiency, and it used classifiers to improve the performance of our classifier. By adding additional layers to the CNN and fine-tuning its parameters, the probability of overfitting the classifier was reduced. For method validation, we compared our proposed models with several benchmarks. MAE, MAPE, MSE, RMSE, the f1 score, recall, precision, and accuracy were the measures used for performance evaluation. Moreover, seven different forms of statistical analysis were given to show why our proposed approaches are preferable. The proposed CNN-CHIO and SVM techniques had the lowest MAPE error rates of 6% and 8%, respectively, and the highest accuracy rates of 95% and 92%, respectively.

1. Introduction

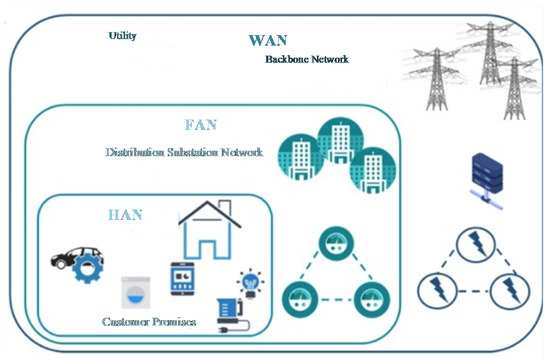

Electricity is now a critical component of economic and social growth. It revolves around electricity. Our lives are thought to be stuck if we do not have electricity. Industrial, commercial, and residential electricity use are classified into three groups. According to [1], residential areas consume nearly 65% of total generated electricity. The majority of energy is lost in the conventional grid during the production, delivery, and supply of electricity. To resolve the aforementioned issues, the smart grid (SG) was developed. By incorporating information and communications technology (ICT) into a traditional grid, it can be transformed into an SG as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical network of smart grid.

1.1. Smart Grid

SG is a smart power system that handles energy generation efficiently. Transmission incorporates emerging technology into a system of energy, allowing users and utilities to communicate in both directions. Power is also a necessity and a valuable asset. Because of the severe energy shortages in the summer, the youth of today are drawn to Singapore. Gadgets in the home are planned with DSM implementing meta-heuristic methods to minimize energy costs and highest point ratios and to find a satisfactory balance between energy costs and customer convenience [2]. By offering effective energy storage, SG assists consumers in achieving efficiency and sustainability. By encouraging customers and providers to exchange information in real-time, the smart meter made it possible to gather sufficient information about future power production. It will ensure that energy output and use are in order. The consumer engages in SG services by shifting demand from maximum to off-hours and conserving resources and saving money on energy [3]. DSM allows customers to monitor their energy usage patterns based on the price set by the utility. The load forecasting benefits market rivals more. Growth, distribution management energy, production planning, performance analysis, and quality control are all things that need to be taken into consideration that depend on upcoming load predictions. Another problem in the energy sector is efficient energy production and use. The primary objective of the consumer and the utility is utility maximization. Energy producers will increase their costs with the aid of reliable load forecasts, while consumers will profit from the low cost of buying electricity. In Singapore, there is no proper energy generation policy. A perfect balance between generated and consumed energy is needed to avoid extra generation. As a result, accurate load forecasting is more critical for market setup management. ISO-NE is also a local distribution system operated by an independent power system, charging the wholesale energy market’s activities. Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island in New England are served by it. The analysis in the study was based on a large collection of ISO NE results. Price is not the only factor that influences the load; temperature, weather conditions, and other factors all affect the electrical load. There is a significant amount of real information [4].

The SG data were carefully scrutinized. The utility takes instructions from the huge quantities of data, which allow it to conduct research and enhance business activity planning and management. To enhance the supply side of SG, a decision-making model was developed. A method for producing is required. The successful choice process leads to a reduction in loss of power, lower energy costs, and lower PAR in the end consumer [5]. Researchers are concentrating on the power scheduling problem in light of these issues. Specific optimization approaches were utilized to address the energy issue [6].

1.2. Problem Statement and Motivation

Each technique in machine learning has advantages and disadvantages. In forecasting the electricity load, however, better performance and accuracy are the primary issues. A large volume of data, on the other hand, makes forecasting more difficult to achieve accuracy. As a result, several strategies have been developed and adapted to fix these problems within the time constraints; however, some challenges remain, such as varying power production and usage to monitor the varying behavior between the power consumption and production patterns [7]. Technique precision and adjusting the hyperparameters for the estimation of electricity demand data [8] and computational difficulty during fuzzy details, such as unnecessary and duplicate features in the data, which increases the learning process calculation time and decreases the reliability of energy load forecasting. A machine learning and deep learning-based model was proposed to solve these challenges. Furthermore, to achieve optimum precision, the hyperparameter values were fine-tuned to use an optimization algorithm. In the function engineering phase, RFE, X-G Boost, and RF were used to remove duplication and clean the files. Finally, the CHIO optimization algorithm was used to determine the optimal hyperparameter values for the convolutional neural network (CNN).

2. Background and Related Work

The term “smart grid” refers to the next generation of power grids, which are power systems in which integrated two-way communication is used to improve energy generation and management. They have the ability in interactions and pervasive computing for stronger control reliability, durability, and protection. Electricity is delivered between producers and customers through a SG. Digital technologies form two-way communication. It is in charge of intelligent appliances. For buyers’ homes or buildings, it is used to save electricity and money and to improve trustworthiness, performance, and accountability [9]. The legacy power system is required to be updated by a SG. It automatically regulates, preserves, and maximizes the operation of the interconnected components. It includes everything from conventional main utilities to emerging regeneration distributed generators, as well as the transmission and distribution networks and systems that link them to industrial consumers and/or home users with heating systems, electric cars, and smart appliances [10]. The bidirectional link of energy and knowledge flows in a SG and creates an integrated, globally dispersed transmission network. It combines the advantages of digital communications with the legacy electricity grid to provide real-time information and to allow near-instantaneous supply and demand management [11]. Many of the SG systems are now in use in other industrial applications, such as sensor networks in manufacturing and wireless networks in telecommunications, and are being developed for use in this modern intelligent and integrated model. Advanced materials; sensing and measuring; enhanced interfaces and decision support, protocols, and classes; and integrated communications are the five main fields in which SG networking systems can be classified. Home area networks (HANs), business area networks (BANs), community area networks (NANs), data centers, and substation automation convergence schemes serve as general frameworks for SG networking infrastructures [12]. Using bi-directional information flow to monitor intelligent equipment at the consumer’s side, SGs deliver electricity between generators (both conventional power generation and distributed generation sources) and end-users (industrial, private, and residential consumers), saving energy and lowering costs while improving system efficiency and service. Smart metering/monitoring strategies can include real-time energy usage as a review and can correlate to demand to/from utilities with the help of a network infrastructure. Customer power demand data and online market prices can be retrieved from data centers from network service centers in order to optimize electricity supply and delivery based on energy consumption. In a dynamic SG architecture, both utilities and consumers will benefit from the widespread rollout of modern SG elements and the integration of current information and control systems used in the legacy power grid [13]. Through incorporating digital connectivity technologies into SGs, it will also improve the reliability of legacy power generation, transmission, and distribution systems, as well as increase the use of sustainable renewable energy. The capacity for various organizations (e.g., intelligent instruments, dedicated software, systems, control center, etc.) to communicate with a network infrastructure is the foundation of a SG. As a result, the construction of a dependable and widespread network infrastructure is critical to the structure and service of SG communication networks [14]. In this regard, the construction of a secure connectivity system for developing robust real-time data transportation across wide area networks (WANs) to the delivery feeder and consumer level is a strategic necessity in supporting this mechanism [15]. Existing electrical utility WANs are built on a mix of networking technologies, including wired technologies like fiber optics, power line communication (PLC) systems, copper-wire lines, and wireless technologies like GSM/GPRS/WiMAX/WLAN and cognitive radio [16]. They are intended to enable monitoring/controlling technologies such as supervisory control and data aAcquisition (SCADA)/energy management systems (EMS), distribution management systems (DMS), enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, generation plant automation, distribution feeder automation, and physical protection for facilities in a variety of locations with insufficient bandwidth. Many technologies, such as SG energy metering, have resulted from a decade of wireless sensor network research. However, sensor networks were unable to communicate with the Internet due to a lack of an IP-based network infrastructure, reducing their real-world influence. The LoWPAN and roll working groups were established by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) to define specifications at different layers of the protocol stack to link low-power devices to the Internet. The authors of [17] explain how the scientific community effectively engages in this process by shaping the creation of these working groups’ specifications and offering open-source implementations. The new transmission infrastructures can expand into virtually universal data transport networks capable of handling both power distribution applications and large amounts of new data generated by SG applications. These networks should be flexible to meet the current and future collection of functions that define the emerging SG networking technical platform, as well as being highly ubiquitous to support the deployment of last-mile communications (i.e., from a backbone to the terminal customers’ locations) [18]. The remainder of this segment covers power line connections, distributed energy storage, smart metering, and tracking and regulation, as well as other important aspects of SG systems.

There are two pieces of the associated work. The literature on energy usage prediction is examined in the first sub-section. A systematic analysis of the literature on power price forecasts is presented in the second sub-section.

2.1. Forecasting Electricity Load

Many techniques for load forecasting have been used in the literature. The training data are difficult to work with as the data are so large and complex. The computing ability of a deep neural network (DNN) allows it to manage big data training. DNN has the capability of accurately forecasting and handling large amounts of data. A broad variety of estimation strategies are covered in the literature. Random forest, naive Bayes, and ARIMA, among other classifier-based techniques, are used for forecasting. Particle swarm optimization (PSO), shallow neural networks (SNN), artificial neural networks (ANN), deep neural networks (DNN), and other artificial intelligence techniques, including shallow neural networks (SNN), artificial neural networks (ANN), deep neural networks (DNN), and others are used. Forecasting the load or price employs a variety of methods. Neural networks have an advantage over other approaches due to automated feature extraction and training methods. In [19], SNN had poor outcomes and an overfitting issue. Regarding price and load forecasting, DNN outperforms SNN. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) and the restricted Boltzmann machine (RBM) were used by the author for forecasting [20]. Data processing and training are handled by RBM, while load forecasting is handled by ReLU. In [21], features were extracted using KPCA, and price forecasting was done using DE-based SVM. Deep auto encoders (DAE) [10] are used to forecast electricity load. DAE is superior in terms of data learning and accuracy. DAE is an unsupervised learning approach that outperforms other methods in terms of achieving high accuracy. In [22], the price was forecasted using the gated recurrent units (GRU) technique. To detect irregular load activity, the Parameter Estimation Method (PEM) was used in [23].

DAE is an unsupervised learning system that achieves high precision while outperforming other methods. It predicts the price using the gated recurrent units (GRU) approach [24]. In [25], the authors used the parameter estimation model (PEM) to identify irregular load activity. For DNN models, the predictability for outcomes is higher. Big data from SG will assist in determining the load and cost trends. It helps utilities create a market, distribution, and inspection routine, which is needed to achieve demand–supply stability. DNN models have a higher degree of predictability. The use of SG’s big data would aid in the analysis of load and cost patterns. It assists utilities in developing a production, distribution, and maintenance strategy, both of which are essential for maintaining production equilibrium. Feature engineering is one of the applications of the classifier. The authors of [26] used a multi-layer neural network (MLNN) model to predict energy costs. However, the computational time and rate of neuron failure in this model are extremely high. Price prediction using hybrid structured deep neural networks was addressed by the authors in [27]. The HSDNN, LSTM, and CNN algorithms were merged. The accuracy of this framework was calculated for different benchmark schemes using performance evaluators like MAE and RMSE. The authors established the predictive performance with the suggested RNN and LSTM named GRU in [28]. Benchmark models such as SARIMA, Markov chain, and naive Bayes were also used in the comparison. To limit forecasting flaws in forecasting, [29] introduced a new framework for STLF named “back neural networks” (BPNN). SSA was used to pre-process the information. This model forecasts using CS and SVM. STLF accuracy was improved in this study. The envelope and embedded strategies were used in [30], and the training data were validated using extra tree regression (ETR) and recursive feature elimination (RFE). LSTM-RNN was used to forecast outcomes after splitting results into preparation and trial sets. It addressed the topic of load demand on the service side [31]. It also encouraged customers to shift their loads from maximum to off moments, saving them money. For DR, two types of architectures have been proposed: user- and utility-centric. The data pre-processing steps were addressed by the authors in [32]. The authors proposed a method for selecting and extracting features. Feature identification and filtration are essential in information pre-processing, and they play a crucial role in reliable forecasting. Forecasting accuracy is improved using normalized data. The actual data are inadequate to estimate demand correctly. A meta training methodology was employed to achieve better results, with the post approach being recommended. A battery was used to store energy in this model. It enabled facility users to discharge excess energy during peak hours when prices were high [33]. Additionally, the authors suggested the battery energy storage system (BESS) as a method for achieving effective cost forecasts. It describes the intra-hour term, which is used to evaluate if the cost is rising or decreasing at the time of publishing. The authors suggested a method for displaying the pattern of electricity use in [34]. With Apache Spark’s library, the k-means method and the cluster validity indices (CVI) were proposed. The RF algorithm was used for prediction by the authors in [35]. Using hourly data from two separate University of North Florida buildings also determined the function value. This model can also predict monthly and yearly consumption patterns, and RF with support vector regression (SVR) were used to analyze the reliability of multiple aspects such as air, heat, moisture, and time type. SVM and artificial neural networks (ANN) were considered classifiers in this analysis. The authors considered improving forecasting accuracy in their proposed model. To extract and pick features from large datasets, RF and regression tree (CART) were employed. The collection of input determines the efficiency and accuracy of resources. The authors of this study concentrated on input selection and accuracy behavior when the training and testing sets were changed. Deep learning (DL) is a particular sub of machine learning that has advanced significantly in recent decades. The increased computing cost of training large models is one of the significant concerns of artificial neural networks. However, when a deep belief network is effectively formed utilizing a method known as greedy layer-wise pre-training, this problem is solved. The experts began to effectively train complex neural networks with more than one layer not visible. The precision and efficiency of these new designs have increased models that have been used to apply generalization technologies in software engineering applications such as object processing, voice identification, and other relevant disciplines. There are a few functions that are focused on deep processing. Estimating performance improved by 30% due to the sorting method in the literature, and some authors utilized CNN to obtain more precise modeling that outperformed the competition in energy-related areas, such as load and price forecasting, in terms of accuracy. The authors in [36,37,38] forecasted the short-term electricity load using the feature extraction methods and also the improved version of a general regression neural network and deep learning methods. The authors achieved accuracy in forecasting the electricity load. The authors of [39] recommended and described how to use DL time-series forecasting techniques for predicting electricity consumption. DL includes models such as the restricted Boltzmann machine (DBM), deep recurrent neural networks (RNN), the stack auto-encoder (SAE), CNN, and others. It is a subset of SAE in which the auto encoder is used as a foundation framework. It involves operational inference [40] to prevent overfitting. SAE aims to reduce the complexity of the data set. DBM is made up of layers, each of which contains hidden Boolean units that allow different layers to communicate with one another. This relation, however, does not exist between each layer [41]. The authors of [40,41,42] increased the accuracy of pricing and load predictions, but they did not account for processing time. Similarly, it solves the problem of load predictions, however, it does not address the issue of overfitting. Additionally, the authors presented the BPNN model for forecasting day-ahead electricity usage in 10; nevertheless, the recommended model’s complexity has risen. Furthermore, we also discuss the literature on electricity price forecasting in the next section.

2.2. Forecasting Electricity Price

In [43], the authors proposed a cost forecast approach based on deep learning methods, which included DNN as an evolution of the DNN framework, the CNN framework, hybrid GRU, traditional MLP, and the hybrid LSTM-DNN framework. The suggested structure was then put up against 27 other schemes as a comparison. The suggested deep learning framework was discovered to improve prediction consistency. A single dataset was used to equate the proposed model to all other schemes. For all real-time experiments, a single dataset is insufficient. GCA, KPCA, and SVM were used to create a dual process for the choice of features, filtration of features, and a massive drop in measurements. However, since the authors used a broad dataset that included prices for wood, steam, gas, wind, and oil, the model’s computation overhead increased. Furthermore, collecting all of these costs in a single real-time database is complex; these resources’ prices cannot be collected in advance. The authors of [44] used DNN templates and the stacked DE noising auto-encoder (SDA). To improve market predictive accuracy, the authors compared various models such as multivariate regression DNN, classical neural networks, and SVM [45]. Additionally, the authors selected features using functional analysis and Bayesian optimization of variance. The creators have suggested the prototype for simultaneously predicting the prices of two markets. Furthermore, prediction can be improved by employing aspects of elimination methods. They reduce the chance of overfitting. The authors, on the other hand, compared the model that had been proposed. This study performed both price and load forecasting. The price prediction accuracy, on the other hand, is insufficient. The authors of [46] looked at a probabilistic model for predicting hourly prices. The generalized extreme learning machine (GELM) was used to make predictions. To speed up the model by reducing computational time, the authors used bootstrapping techniques. On the other hand, it does not work best for massive, large datasets, and the volume of information increased linearly. Oveis Abedinia et al. focused on attribute choice to improve prediction. For feature selection, these proposed models use information-theoretic parameters such as information gain (IG) and mutual information (MI). The hybrid filter-wrapper solution is another contribution of this study. In [47,48], the authors suggested a mixed algorithm for cost and demand modeling. Quasi-oppositional artificial bee colony (QOABC) and artificial bee colony optimization (ABCO) algorithms were updated by the researchers. Dogan Keles et al. are a group of researchers who came up with a novel solution. ANN [49] was used to propose a system. To find the best ANN parameters, the authors used a variety of clustering algorithms. The dynamic choice algorithm neural network (DCANN) was introduced by [50]. This design is used to predict rates for the next day. To unplug poor results and recognize acceptable inputs for a teaching method, this method integrates supervised and unsupervised training. The researchers of [51] developed a mixed design built on the neural network of Guo-Feng Fan et al. By combining the bi-square kernel regression model with the phase space reconstruction algorithm, the PSR-BSK model [52], a new model for predicting energy load, has been suggested. To validate the model’s performance, the authors used an hourly dataset from NYISO in the New South Wales and the United States market. To extend the community in CS and to maximize the search space in [53], the authors suggested a dual SVR-chaotic cuckoo search (SVRCCS) framework. The authors recommended SSVRCCS, a seasonal CCS with SVR, to work with the load’s periodic linear development. Owing to a large number of iterations, the computing period, on the other hand, was raised. It is impossible to overstate the value of contact between SG and its users. In the sense of creation in smart cities, the authors reduced energy usage and increased the traffic speed of device-to-device (D2D) interaction, also known as smart interaction, in [54]; smart communication is a serious issue that needs to be tackled. The authors broke the problem down into two parts to solving it: uplink subcarrier assignment (SA) and power allocation (PA) with joint optimization. The transmission power was distributed to all sub-carriers using a heuristic algorithm for SA. After that, an optimal PA algorithm was implemented to tackle the sub problem of convex similarity. The contact problems between SG and consumers were addressed by the authors in [55]. The authors provided a brief overview of the wireless and wired communication systems, as well as the various communication protocols. According to the cyber and physical frameworks, security concerns of hardware and software were also addressed. The authors discussed advanced metering infrastructure as well as automatic meter readings for customer information gathered via cables and portable links. The authors of [56] showed how SG and customers communicate digitally and with advanced control technologies. For connected and portable communication, the functionality, safety, robustness, efficiency, range, speed, power consumption, and protocols of wireless and other innovations were contrasted. API, HEMS, DA, DER, and EVS were some of the contact applications used by SG and consumers. To evaluate the efficiency of D2D delivery, in their study [57], the authors proposed an energy efficient delivery system (ECDS). D2D is a dependable and effective method of communication. It is not necessary to have any prior knowledge of content delivery, mobile mobility, or user demand. The energy conservation design system (ECDS) is used in smart cities to reduce their energy consumption. For a random and complex world, this method achieves the optimal solution.

Only a few logical operations were performed by ECDS, which made decisions based on local data from each system. The authors in [58,59] forecast the electricity price using the multi-step methods and dual decomposition methods. Furthermore, they tuned the parameters of the model using multi-objective optimization methods, which led to better forecasting.

SG can quickly predict the demand for consumers’ energy usage after receiving information about the use of various devices through a green communication system. To maintain production and need equilibrium, load and price prediction are critical. Load balancing is necessary to prevent power shortages and over-production. When resources are abundant, storing them is very costly. A blackout could occur if a generation falls short of demand. The utility can generate electricity with the help of generators and other expensive tools. The cost of energy rises in all situations. A summary of related work is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarized related work.

3. System Models

This stud proposes two methods for forecasting energy load and price. Since they use similar strategies, these two models are related.

The last design, on the other hand, is utilized to predict electricity demand, while the second framework is utilized to predict energy costs. The models that were suggested are the electricity price forecasting model and the electricity load forecasting model.

3.1. Model for Predicting Electricity Load and Price

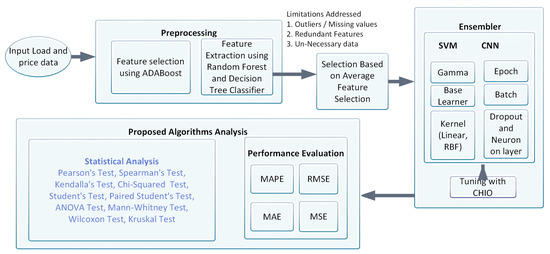

Figure 2 depicts the load forecasting model. To predict the electricity load and price, take the following steps:

Figure 2.

System model for electricity price and load forecasting.

- Data input (i.e., dataset).

- Feature extraction using RFE.

- Feature selection using RF and XG-Boost.

- Splitting of data into training and testing.

- Load the CNN layers and parameters.

- Tuning the CNN parameters using CHIO and then model compiling.

- Predicted price and load.

- Performance evaluation.

- Statistical analysis.

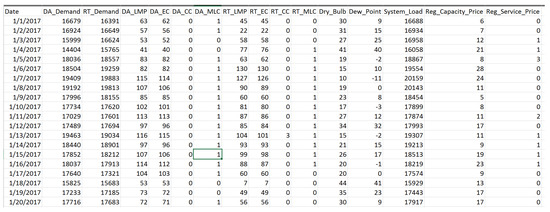

3.2. Data Collection

ISO-NE is the name given to the electricity energy sector in New England [60]. It is in charge of producing, processing, and delivering electric energy to end-users in the processing, retail, and industrial areas. ISO-NE provides a large amount of data about, among other things, load, cost, production, and supply. The load data for 2018 come from ISO-NE, and they were used to incorporate the proposed models. This study used daily energy load data from Independent System Operator New England (ISO NE) (https://www.iso-ne.com, accessed on: 29 June 2021) for three years, from January 2017 to December 2019. It provides power to a number of English towns. Weather, temperature, humidity, and other dependent and independent data were included in the dataset. Our goal data are in a column called “electricity load”. The target data were affected by all functionality other than the target features. The energy load demand pattern of a similar month in each year is roughly the same. As a result, we took three years’ worth of results, or 36 months. To that end, the dataset was split into two sets: preparation and research. As a result, 90% of the data was used for teaching, and 10% was used for research, since the more data generated for training, the higher the model’s learning rate would be. Furthermore, data from previous years’ equivalent months, such as January 2017, January 2018, and January 2019, were combined to provide a short-term load forecast for December 2019. The data in the dataset were organized by month, which aids in the better training of our model to determine the load pattern of months. All data from the first week of December 2019, i.e., 1 December 2019 to 7 December 2019, were used as preparation for weekly forecasting. In the first week of December, the teaching model was put to the test. Furthermore, the first five months of 2019 were also taken into account for preparation and research. Similarly, except for January 2019, all data were used for preparation and monitoring. In addition, the same situation was pursued in February, March, April, and May 2019. The suggested model’s effectiveness is shown by the simulation and the results. The data description and function names are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Dataset overview.

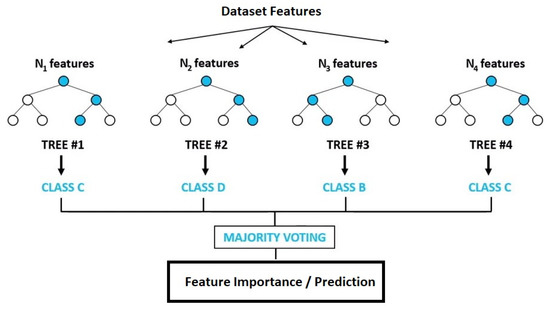

3.3. Feature Extraction Using (RFE)

Recursive feature elimination (RFE) is a tool for obtaining a set of attributes from a database [61,62,63]. It replaces the lowest feature recursively before the required set of attributes is achieved. RFE involves the selection of many features; however, determining how many features are most important is difficult in advance as in Figure 4. To solve this dilemma, cross-validation was combined with RFE. Cross-validation tests the reliability of various categories and picks the most reliable.

Figure 4.

Random forest classifier.

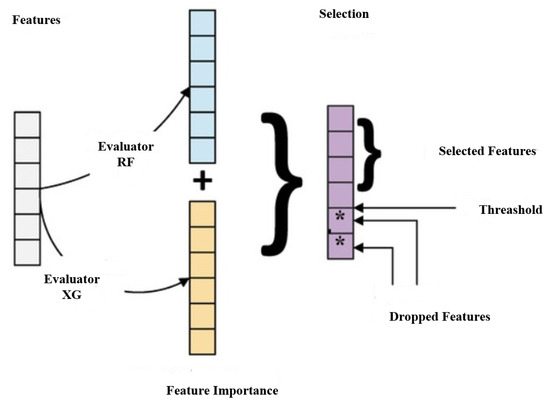

3.4. Feature Selection

The method of selecting more important features is known as feature selection [64,65,66]. The number of features in the data set was reduced. Every feature’s importance was calculated using RF. It was done to exclude the less relevant functions, and a hybrid solution was proposed for the final selection, which was a mixture of XG-boost and RF as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Feature selection.

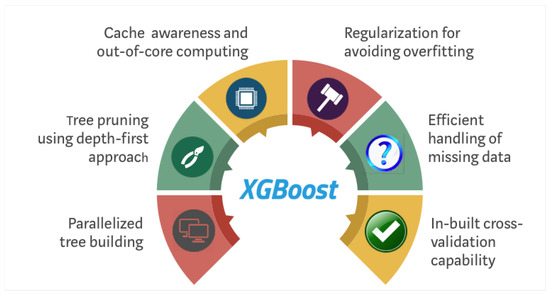

XG-Boost

XG-boost gradient boosting (Extreme) is an optimized gradient boosting library [67]. It is made to be extremely compact, adaptable, and efficient. It uses the gradient method boosting and tree boosting in tandem to effectively and reliably produce accurate classification issues. It can be used to address estimation, grouping, and rating concerns. It is a library that is free to use. It comes in a variety of languages, including C++ and Python, for a variety of platforms of activity. The abstract diagram of XG-boost is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

XG-boost abstract model.

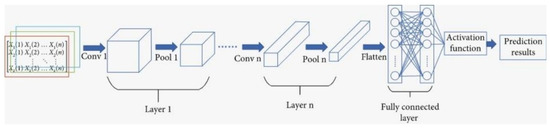

3.5. Convolutional Neural Network

CNN is a type of neural network that belongs to the category of supervised deep learning prototypes [68]. In CNN implementation, firstly, a sequential model is implemented. It builds model layers upon layers. A prediction framework is built using four distinct levels in this design. A second surface, the convolution layer, is added to verify the neurons with outcomes that are related to the input layer. The convolutional layer receives m*r as its input. The dimensions of the height and width of the matrix are denoted by m and r, respectively. In cases where the matrix’s dimension is less than the query, the kernel size will be used as a filter. The network’s linked structure is determined by the filter’s height. The equation will be used to calculate Relu, which will be used as an activation function. If the input value is negative, Relu returns 0; otherwise, it produces the same result, where x is the inputs:

Following it, as a network’s third tier, max-pooling is used to provide a matrix with small numbers. Max pooling, for example, chooses the most significant value from the various matrices. Then, using these values, it makes a small matrix.

For example, where p stands for padding and f stands for the range of filters, and n is the length of content: 32 × 32 × 1. To prevent the issue of over-fitting, flatten layer was used as the fourth layer to turn all of the neurons into a single associated layer using a dropout layer. Each entity in the system is attached to the others. Early on in the process, the importance of the neuron failure rate was revealed. If the value of a network’s failure rate in a stable state cannot be found by soon stopping the process it can be tested again. Then, to prevent overfitting, one switches to the dropout layer and applies the dense layer once more. The prediction result is finally shown in the output layer. The optimizer in this model is called “Adam”. CNN forecasted energy demand and price under various scenarios in this study. Algorithm 1 illustrates the proposed model step by step. The architecture of CNN is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

CNN architecture.

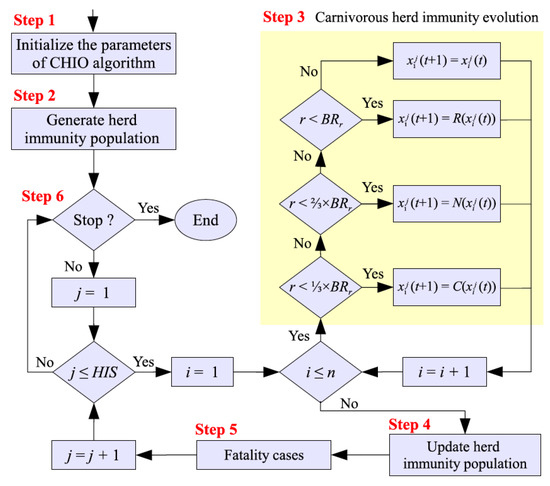

3.6. Coronavirus Herd Immunity Optimization

In this study, we utilized the CHIO algorithm [68] to tune the parameters of Adaboost. CHIO is used to minimize time complexity and increase precision in AdaBoost performance measurement. The concept of coronavirus herd immunity optimization (CHIO) was inspired by preventing the COVID-19 disease outbreak. The rate at which coronavirus infection spreads is regulated by how affected people interact with others in society. To protect all members of the community from the condition, health authorities advise social distancing. Herd immunity is a state attained by a species when the majority of its population is immune, inhibiting disease transmission. These concepts are represented by optimization principles. CHIO is a combination of herd immunity and social distancing strategies. Human cases are classified into three types for herd immunity: vulnerable, immuned, and contaminated. This is to determine whether the newly developed method employs social distancing strategies to update the genes. Figure 8 depicts the flow of the CHIO algorithm.

Figure 8.

CHIO algorithm flow chart.

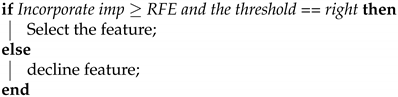

Algorithm 1 illustrates the proposed model step by step. The proposed algorithm of our work is:

| Algorithm 1: Proposed Work Algorithm |

| Result: Electricity price and load forecasting X: data features; Y: data with a purpose; /* Separate the data into two categories: preparation and testing. */ ; split (x, y) = x train, x test, y train, y test; RFE (5, x train, y train); Selected_ function; /* Selection of hybrid features */ ; Incorporateimp = RFimp + XGimp; /* Using RF and XG-boost, measure value */ ; RF imp = RF calculates importance; /* RFE is a technique for extracting features. */ ;  CNN-CHIO predicting the future with fine-tuned; Performance evaluation test, compare predictions; |

3.7. Performance Evaluation

Based on efficiency metrics, the suggested models were evaluated: MSE, MAPE, MAE, and RMSE. Equations (2)–(5) [22] provide the MSE, MAE, RMSE, and MAPE formulas. On the data collection of ISO-NE, Table 2 and Table 3 displays the measurement of output measures of various methods. The MAPE is calculated using the formula:

Table 2.

Performance evaluation values of electricity load forecasting.

Table 3.

Electricity price forecasting performance evaluation values.

The RMSE is calculated using the formula:

The MAE and MSE are calculated using the formula:

4. Simulation Results and Discussions

The implementation effects of our proposed model are explained in terms of their performance metrics in this section. We simulated our model on the following system specifications: 16 GB RAM and a 4.8 GHZ Core i7 processor. The IDE environment Anaconda (Spyder) and the Python language were used.

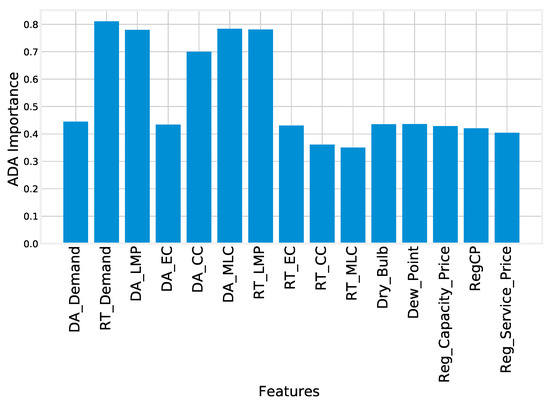

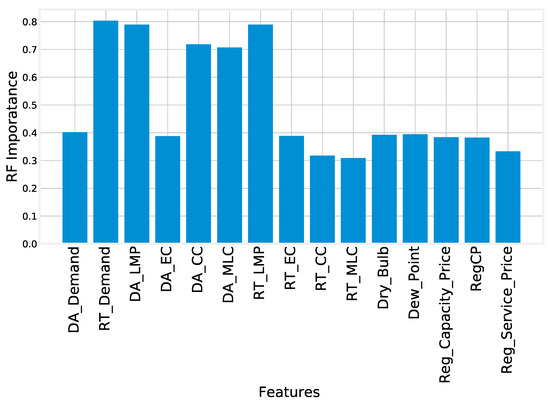

4.1. Electricity Load Forecasting

Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the feature importance calculated by machine learning techniques, i.e., AdaBoost and RF. The feature importance means how much a feature impacts the target feature, i.e., electricity load. The high importance value of the feature means an important influence on the targeted function. The high impact of the feature shows the high relevancy towards the target. Changes in these relevant features can cause a huge impact on the target. Features with a low importance value were considered as low-impact features. If these features are removed, they had no impact or low impact on the target. Getting rid of the features that are not needed improves the simulation time and reduces computational complexity. Figure 9 shows the feature score/importance calculated by the AdaBoost technique, and Figure 10 displays the importance of features calculated by RF.

Figure 9.

ADABoost-computed feature importance.

Figure 10.

Random-forest-computed feature importance.

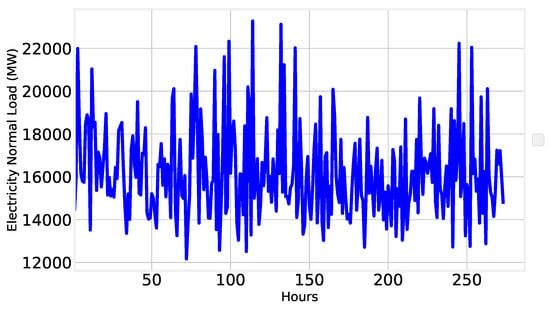

Figure 11 shows the daily normal load electricity of the years 2012–2020. We can see that the normal load had some different patterns with respect to time. Figure 11 also comprises the historical consumption pattern of consumers.

Figure 11.

Normal electricity load. of ISO-NE 2012–2020.

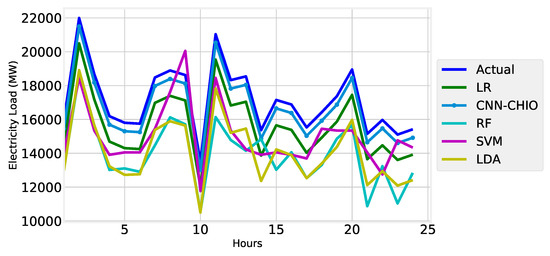

Using the modified machine learning algorithm SVM and the deep learning algorithm CNN embedded with a GRU layer, we forecast the electricity load of one day as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

One-day electricity load forecast.

Furthermore, with the same methodology, we forecasted two-day, three-day, and one-week upcoming electricity loads with a high accuracy of 96%.

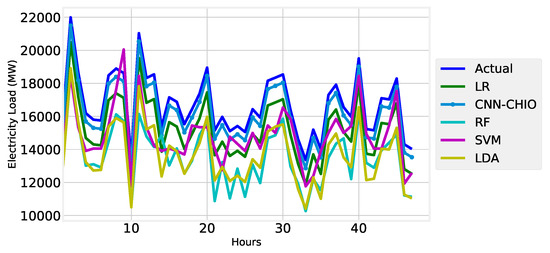

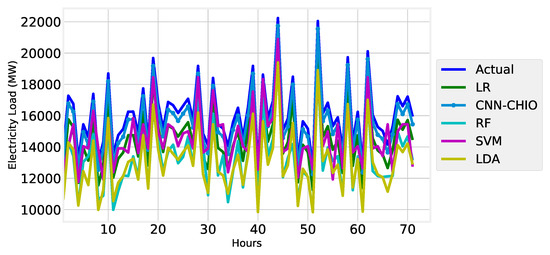

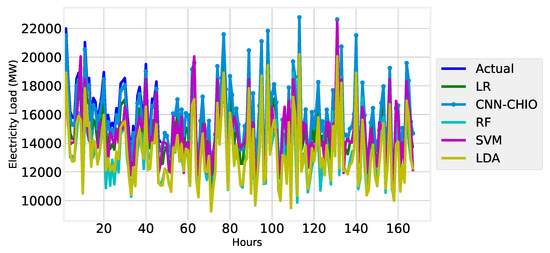

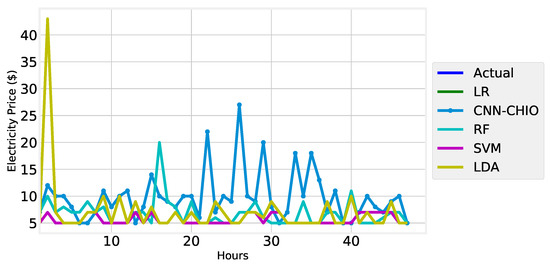

In Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15, we can see that our proposed algorithm forecasts better than the other benchmark algorithms. The proposed algorithm CNN-CHIO performed better than the other proposed algorithms, and SVM performed better than the most up-to-date algorithms.

Figure 13.

Two-day load forecast.

Figure 14.

Three-day load forecast.

Figure 15.

One-week load forecast.

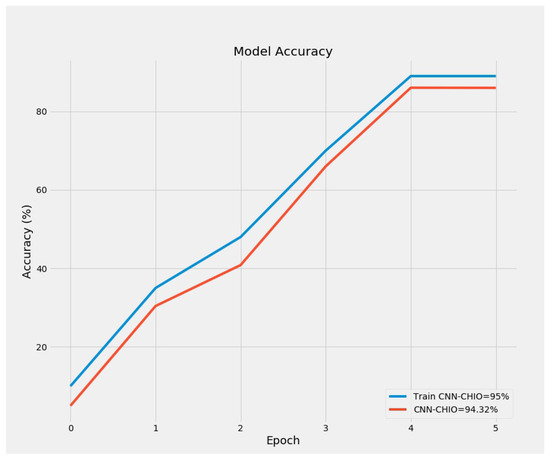

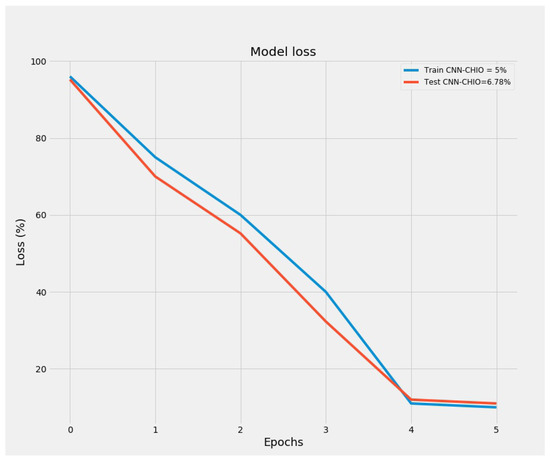

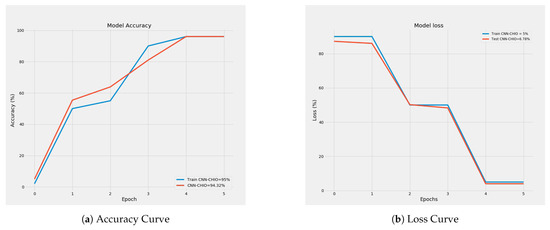

Figure 16 and Figure 17 shows the accuracy and loss curve of our proposed model. In Figure 16, we can see that the curve of training and the testing accuracy was increasing, while Figure 17 shows the decrease in the model loss value. The increase in accuracy and the decrease in the loss curve shows the superiority of the model that we proposed, which means our proposed model performed better in achieving the accuracy.

Figure 16.

Accuracy curve of electricity load model.

Figure 17.

Loss curve of electricity load model.

4.2. Electricity Price Forecasting

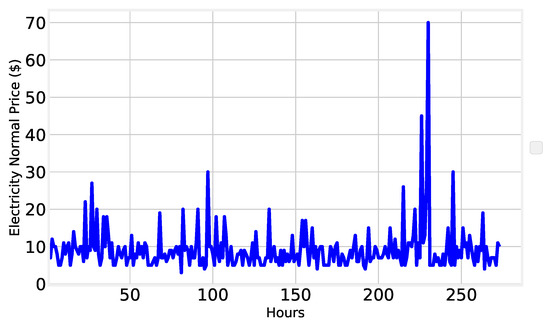

Figure 18 shows the normal electricity price from 2012–2020. The price of electricity varied with time. It also shows the seasonal change in the electricity price.

Figure 18.

Normal electricity price of ISO-NE 2012–2020.

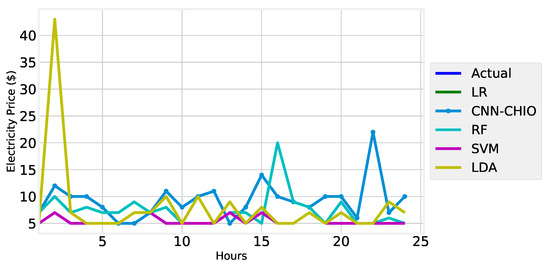

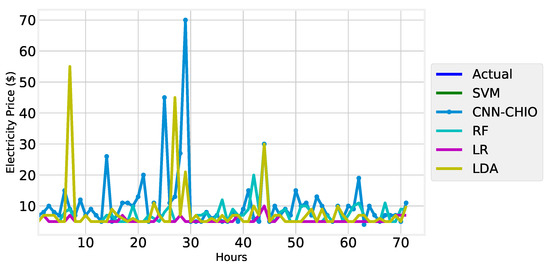

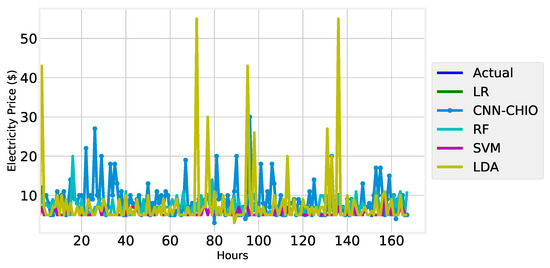

Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22 shows the electricity price forecasting of 24 h, two days, three days, and one week. From Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22, it was determined that the proposed algorithm worked well in terms of predicting the electricity. In comparison with the actual electricity price, we can see that the curve of the proposed algorithm is near to the actual. In forecasting the short-term electricity price, our proposed model outperformed benchmark algorithms.

Figure 19.

24-h electricity price forecast.

Figure 20.

Two-day electricity price forecast.

Figure 21.

Three-day electricity price forecast.

Figure 22.

One-week electricity price forecast.

Figure 23 describes the proposed model’s loss and accuracy. The proposed model’s accuracy was increasing, and the loss value was decreasing with the number of iterations. Our proposed methodology performed better in achieving the accuracy of 92% and 90%, respectively.

Figure 23.

Electricity price forecasting model accuracy and loss.

4.3. Performance Evaluation of Electricity Price and Load Forecasting

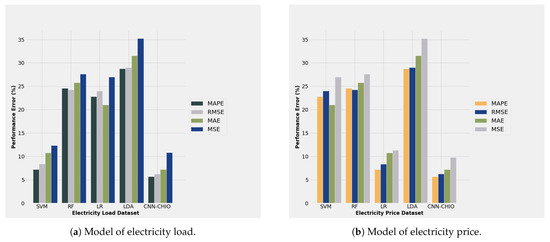

This section evaluates the proposed model and benchmark schemes using performance evaluation techniques, performance error metrics, and statistical analysis. Figure 24 shows the performance evaluation using the error metrics MAPE, MSE, RMSE, and MAE. We can determine in Figure 24 that the proposed models SVM and CNN-CHIO had the lowest error rate compared with the RF, LDA, and RF techniques. The LDA technique had the highest error rate in forecasting the electricity price and load. The lowest error showed the superiority of the proposed techniques.

Figure 24.

Performance error metrics of proposed and benchmark techniques.

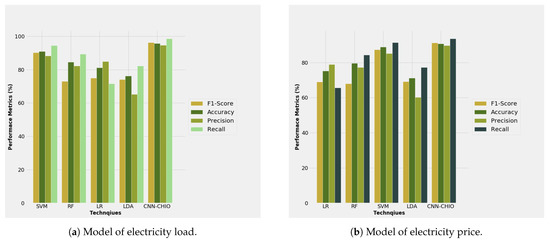

The performance evaluation metrics, i.e. precision, F-score, accuracy, and recall, were also used to assess the proposed model and to compare with the benchmark algorithm.

In Figure 25, the performance evaluation of the electricity price and the electricity load forecasting model is shown. Figure 25 clearly shows that the accuracy of CNN-CHIO and SVM was higher than the other benchmark algorithm. The optimization part of the proposed model provided the exact values to the models, which increased the accuracy of our proposed model.

Figure 25.

Evaluation metrics performance of proposed and benchmark techniques.

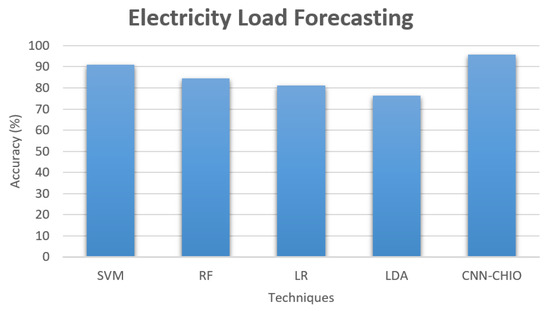

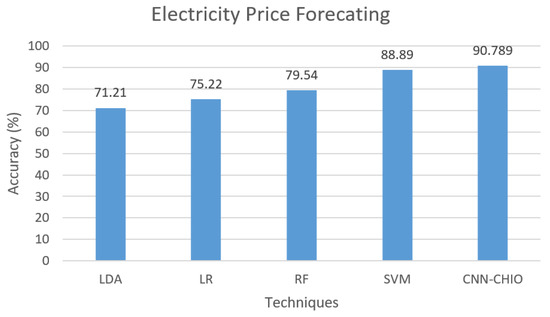

Our proposed model’s, i.e., SVM’s and CNN-CHIO’s, accuracy in electricity price forecasting, was 92% and 90%, respectively. Furthermore, SVM achieved 95% accuracy, while CNN-CHIO achieved 92% accuracy in terms of the electricity load forecasting model.

Table 2 and Table 3 shows the performance evaluation of electricity load and price forecasting values in tabular form. Our proposed technique CNN-CHIO achieved 95% accuracy, and SVM achieved 90.89% accuracy in load forecasting with 90% and 87.32% accuracy in price forecasting, respectively, as shown in Figure 26 and Figure 27. Our proposed technique outperformed the state of the art.

Figure 26.

Electricity load forecasting accuracy proposed vs. benchmark techniques.

Figure 27.

Electricity price forecasting accuracy proposed vs. benchmark techniques.

Table 4 shows the statistical analysis of the proposed algorithm. We applied ten statistical techniques to analyze our proposed model. The supremacy of the proposed model can also be identified in the analysis table.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of proposed techniques vs. benchmark algo.

5. Conclusions

We proposed a CNN-GRU hybrid model tuned with a novel optimization technique CHIO was used to simulate energy use and energy price in residential buildings in this study. The proposed model was validated using a publicly accessible dataset from ISONE. Since the input data were non-linear, we first normalized them using a regular min–max scalar, then we fed the normalized data into the feature selection method using AdaBoost and extracted the feature importance and selected the features with high importance. We applied RF and RFE to remove the redundant features and selected the optimum and most relevant features. The preprocessing process was performed to improve the training of our model and to decrease the computational complexity. Following that, we looked at various machine learning and deep learning approaches before settling on a mixed model that merged CNN and GRU. We first used feature engineering to extract spatial features. We then fed them into our tuned CNN-CHIO and SVM to simulate temporal characteristics corresponding to the time series data entry. As opposed to other baseline models, the proposed model performed well, suggesting that our presented, existing buildings model must be able to be found in actual life. Furthermore, our proposed model of CNN-CHIO and SVM achieved 95% and 92% accuracy in load forecasting and 92% and 89% accuracy in price forecasting, respectively. In future work, we intend to validate the proposed CNN-GRU and SVM model on various datasets and enhance the model’s accuracy by incorporating fuzzy logic concepts. The model is currently being based on residential building results, but it will also be tested on commercial loads and price datasets. We predicted short-term electricity consumption and electricity prices in this study; however, our long-term aim is to assess the model’s efficiency in predicting medium- and long-term electricity consumption and electricity prices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and N.A.; methodology, S.A., N.A., U.F. and M.J.A.; software, S.A. and M.J.A.; validation, F.R.A. and G.R.; formal analysis, U.F. and A.T.A.; investigation, A.T.A.; resources, A.T.A.; data curation, S.A. and U.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A., N.A. and U.F.; writing—review and editing, F.R.A., G.R., S.I.H. and R.B.; visualization, A.T.A.; supervision, A.T.A. and R.B.; project administration, A.T.A.; funding acquisition, F.R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC is funded by Taif University Researchers Supporting Project Number (TURSP-2020/331), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study can be found here: https://www.iso-ne.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from Taif University Researchers Supporting Project Number (TURSP-2020/331), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interrest.

References

- Aslam, S.; Herodotou, H.; Mohsin, S.M.; Javaid, N.; Ashraf, N.; Aslam, S. A survey on deep learning methods for power load and renewable energy forecasting in smart microgrids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuen, C.; Huang, S.; Hassan, N.; Wang, X.; Xie, S. Peak-to-average ratio constrained demand-side management with consumer’s preference in residential smart grid. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2014, 8, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurangzeb, K.; Aslam, S.; Mohsin, S.M.; Alhussein, M. A fair pricing mechanism in smart grids for low energy consumption users. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 22035–22044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, C.L.; Watson, S.; Majithia, S. Analyzing the impact of weather variables on monthly electricity demand. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2005, 20, 2078–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, P. Demand response and smart grids—A survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Iqbal, Z.; Javaid, N.; Khan, Z.A.; Aurangzeb, K.; Haider, S.I. Towards efficient energy management of smart buildings exploiting heuristic optimization with real time and critical peak pricing schemes. Energies 2017, 10, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Ghadimi, N. Electricity load forecasting by an improved forecast engine for building level consumers. Energy 2017, 139, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.B.; Zheng, W.Z.; Kong, J.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Bai, Y.T.; Su, T.L.; Lin, S. Deep-Learning Forecasting Method for Electric Power Load via Attention-Based Encoder-Decoder with Bayesian Optimization. Energies 2021, 14, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kubicki, S.; Guerriero, A.; Rezgui, Y. Review of building energy performance certification schemes towards future improvement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, R.; Gross, R.; Hanna, R.; Rhodes, A.; Green, T. The Demand Response Technology Cluster: Accelerating UK residential consumer engagement with time-of-use tariffs, electric vehicles and smart meters via digital comparison tools. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, A.; Conti, M. Key management systems for smart grid advanced metering infrastructure: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2831–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dileep, G. A survey on smart grid technologies and applications. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2589–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.H.; Huang, C.J. An electricity price forecasting model by hybrid structured deep neural networks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ugurlu, U.; Oksuz, I.; Tas, O. Electricity price forecasting using recurrent neural networks. Energies 2018, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eapen, R.; Simon, S. Performance analysis of combined similar day and day ahead short term electrical load forecasting using sequential hybrid neural networks. IETE J. Res. 2019, 65, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K. Short-term electric load forecasting based on singular spectrum analysis and support vector machine optimized by Cuckoo search algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 146, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.; Deshmukh, S.; Agrawal, R. Electric power price forecasting using data mining techniques. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Data Management, Analytics and Innovation (ICDMAI), Pune, India, 24–26 February 2017; pp. 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bouktif, S.; Fiaz, A.; Ouni, A.; Serhani, M. Optimal deep learning lstm model for electric load forecasting using feature selection and genetic algorithm: Comparison with machine learning approaches. Energies 2018, 11, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keles, D.; Scelle, J.; Paraschiv, F.; Fichtner, W. Extended forecast methods for day-ahead electricity spot prices applying artificial neural networks. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhong, H.; Xie, L.; Xia, Q.; Kang, C. Month ahead average daily electricity price profile forecasting based on a hybrid nonlinear regression and SVM model: An ERCOT case study. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2018, 6, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, J.; De Ridder, F.; De Schutter, B. Forecasting spot electricity prices: Deep learning approaches and empirical comparison of traditional algorithms. Appl. Energy 2018, 221, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi, N.; Akbarimajd, A.; Shayeghi, H.; Abedinia, O. Two stage forecast engine with feature selection technique and improved meta-heuristic algorithm for electricity load forecasting. Energy 2018, 161, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.; Singh, M.; Kumar, N.; Response, C.A. Scheme for Peak Load Reduction in Smart Grid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 8993–9004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitsaz, H.; Zamani-Dehkordi, P.; Zareipour, H.; Parikh, P. Electricity price forecasting for operational scheduling of behind-the-meter storage systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 9, 6612–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Chacón, R.; Luna-Romera, J.M.; Troncoso, A.; Martínez-Álvarez, F.; Riquelme, J.C. Big data analytics for discovering electricity consumption patterns in smart cities. Energies 2018, 11, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, R.; Srinivasan, R.; Ahrentzen, S. Random Forest based hourly building energy prediction. Energy Build. 2018, 171, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahouar, A.; Slama, J. Day-ahead load forecast using random forest and expert input selection. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 103, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Zomaya, A. Robust big data analytics for electricity price forecasting in the smart grid. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2017, 5, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J. Short-term electricity price forecasting with stacked denoising autoencoders. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 32, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, J.; De Ridder, F.; Vrancx, P.; De Schutter, B. Forecasting day-ahead electricity prices in Europe: The importance of considering market integration. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, E.; Bouwman, K.; Van Dijk, D. Forecasting day-ahead electricity prices: Utilizing hourly prices. Energy Econ. 2015, 50, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mujeeb, S.; Javaid, N.; Akbar, M.; Khalid, R.; Nazeer, O.; Khan, M. Big data analytics for price and load forecasting in smart grids. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Broadband and Wireless Computing, Communication and Applications, Taichung, Taiwan, 27–29 October 2018; pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiei, M.; Niknam, T.; Khooban, M.H. Probabilistic forecasting of hourly electricity price by generalization of ELM for usage in improved wavelet neural network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2016, 13, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedinia, O.; Amjady, N.; Zareipour, H. A new feature selection technique for load and price forecast of electrical power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 32, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Shayeghi, H.; Moradzadeh, M.; Nooshyar, M. A novel hybrid algorithm for electricity price and load forecasting in smart grids with demand-side management. Appl. Energy 2016, 177, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Niu, D.; Hong, W.C. Short term load forecasting based on feature extraction and improved general regression neural network model. Energy 2019, 166, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, K.; Wang, Q.; He, Z.; Hu, J.; He, J. Short-term load forecasting with deep residual networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 3943–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, B.; Xu, Y.; Xu, T.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Z. Multi-scale convolutional neural network with time-cognition for multi-step short-term load forecasting. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 88058–88071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, H.; Ghasemi, A.; Moradzadeh, M.; Nooshyar, M. Simultaneous day-ahead forecasting of electricity price and load in smart grids. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 95, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Song, Y.; Zhao, J. A novel model: Dynamic choice artificial neural network (DCANN) for an electricity price forecasting system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 48, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, H.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, R. A hybrid approach to price forecasting incorporating exogenous variables for a day ahead electricity market. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 1st International Conference on Power Electronics, Intelligent Control and Energy Systems (ICPEICES), Delhi, India, 4–6 July 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.F.; Peng, L.L.; Hong, W.C. Short term load forecasting based on phase space reconstruction algorithm and bi-square kernel regression model. Appl. Energy 2018, 224, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hong, W.C. A hybrid seasonal mechanism with a chaotic cuckoo search algorithm with a support vector regression model for electric load forecasting. Energies 2018, 11, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kai, C.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, T. Energy-efficient device-to-device communications for green smart cities. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 1542–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabalci, Y. A survey on smart metering and smart grid communication. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Javaid, N.; Razzaq, S. A review of wireless communications for smart grid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, D.; Chen, J.; Dong, Z. Greening the smart cities: Energy-efficient massive content delivery via D2D communications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 14, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Sopian, W.; Arasid, W.; Nandiyanto, A.; Danuwijaya, A.; Abdullah, C. Short-term peak load forecasting using PSO-ANN methods: The case of Indonesia. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2018, 13, 2395–2404. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah, S.; Deo, R.; Shojafar, M.; Conti, M.; Shamshirband, S. Computational intelligence approaches for energy load forecasting in smart energy management grids: State of the art, future challenges, and research directions. Energies 2018, 11, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, G.B.; Zhu, Q.Y.; Siew, C.K. Extreme learning machine: Theory and applications. Neurocomputing 2006, 70, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Domínguez, A.; Padierna, L.C.; Valadez, J.M.C.; Puga-Soberanes, H.J.; Fraire, H.J. Optimal hyper-parameter tuning of SVM classifiers with application to medical diagnosis. IEEE Access 2017, 6, 7164–7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Xia, J.; Liu, A.; Li, P. States prediction for solar power and wind speed using BBA-SVM. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2019, 13, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, S.; Brito, T.; Welling, D. Measures of model performance based on the log accuracy ratio. Space Weather 2018, 16, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohi-Fayegh, S.; Rosen, M. A review of energy storage types, applications and recent developments. J. Energy Storage 2020, 27, 101047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, F.; Ipakchi, A. Demand response as a market resource under the smart grid paradigm. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2010, 1, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadari, S. Electric System Operations: Evolving to the Modern Grid; Artech House: Braga, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ayub, N.; Irfan, M.; Awais, M.; Ali, U.; Ali, T.; Hamdi, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Muhammad, F. Big Data Analytics for Short and Medium-Term Electricity Load Forecasting Using an AI Techniques Ensembler. Energies 2020, 13, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Niu, T.; Du, P. A novel system for multi-step electricity price forecasting for electricity market management. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 88, 106029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Niu, T.; Du, P. A hybrid forecasting system based on a dual decomposition strategy and multi-objective optimization for electricity price forecasting. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 1205–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Ayub, N.; Ali, T.; Irfan, M.; Awais, M.; Shiraz, M.; Glowacz, A. Towards short term electricity load forecasting using improved support vector machine and extreme learning machine. Energies 2020, 13, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Wollenberg, B. Toward a smart grid: Power delivery for the 21st century. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2005, 3, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.; Villacci, D. Performance analysis of low earth orbit satellites for power system communication. Electric Power Syst. Res. 2005, 73, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahli, S.; Shiraz, M.; Ayub, N. Electricity Price Forecasting for Cloud Computing Using an Enhanced Machine Learning Model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 200971–200981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupp, J.; Beehler, M. Implementing smart grid communications. TECHBriefs 2008, 4, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassemi, A.; Bavarian, S.; Lampe, L. Cognitive radio for smart grid communications. In Proceedings of the 2010 First IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 4–6 October 2010; pp. 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.; Terzis, A.; Dawson-Haggerty, S.; Culler, D.; Hui, J.; Levis, P. Connecting low-power and lossy networks to the internet. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2011, 49, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Aimal, S.; Javaid, N.; Rehman, A.; Ayub, N.; Sultana, T.; Tahir, A. Data analytics for electricity load and price forecasting in the smart grid. In Proceedings of the Workshops of the International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Matsue, Japan, 27–29 March 2019; pp. 582–591. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Betar, M.A.; Alyasseri, Z.A.A.; Awadallah, M.A.; Doush, I.A. Coronavirus herd immunity optimizer (CHIO). Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 5011–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).