Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil: A Review on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- How consumers perceive the sustainability labels on olive oil?

- -

- How the use of sustainability labels (separately or together) impact consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay for olive oil.

2. Background: Sustainability Labeling on Food Products

3. Methodology and Materials

3.1. Study Selection

- Population—independent consumers and/or purchasers of olive oil aged 18–75 years old.

- Intervention—labels/logos/claims/information linked to economic, environmental and/or social or cultural sustainability of olive oil.

- Comparison—consumer preference for the different sustainability labels.

- Outcomes—qualitative results included consumer evaluation, interpretation and liking of different labels. Empirical results included attribute utility estimates and willingness-to-pay.

- Situation—no geographical limits.

- Type of study—primary research studies only.

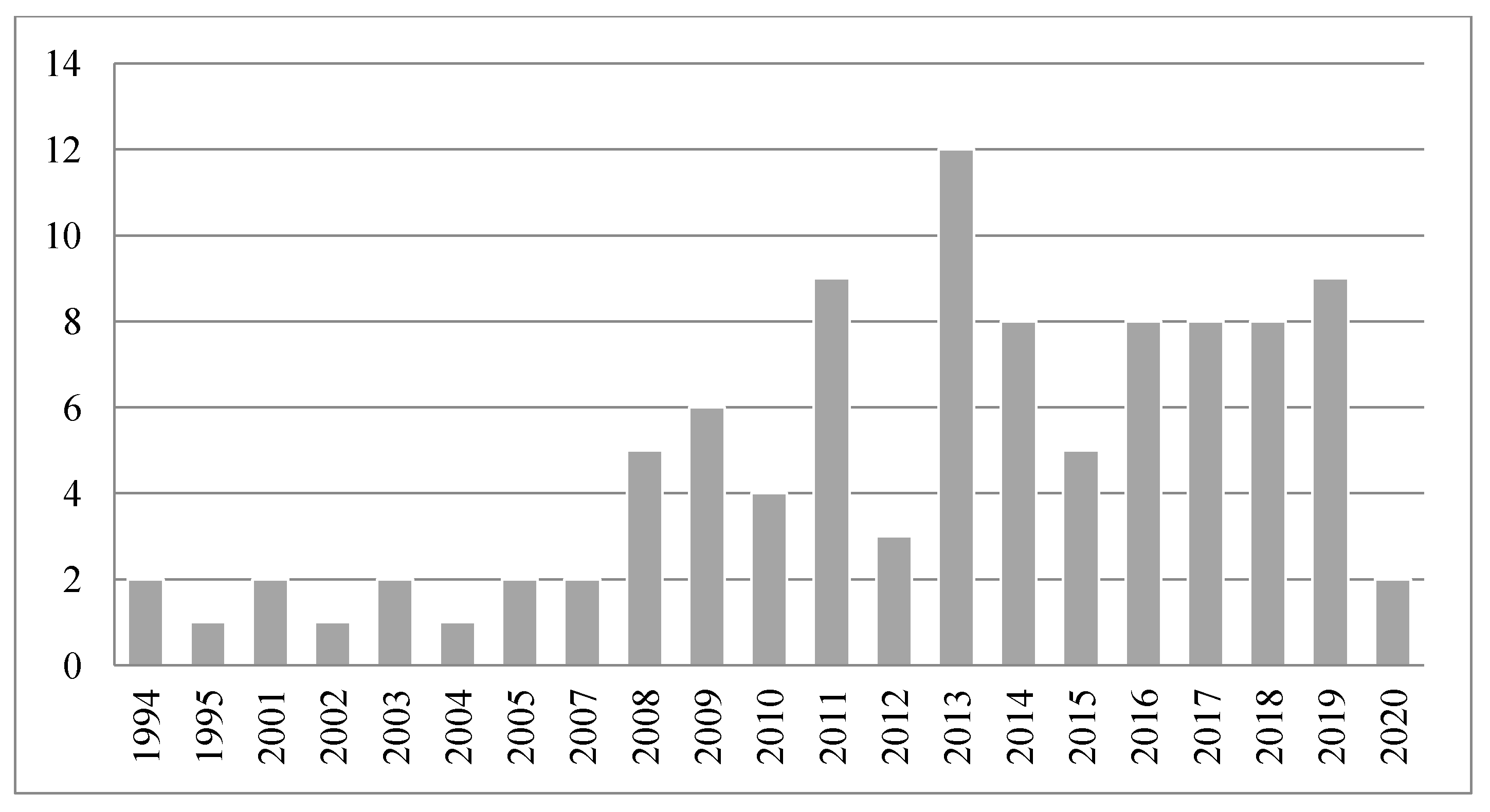

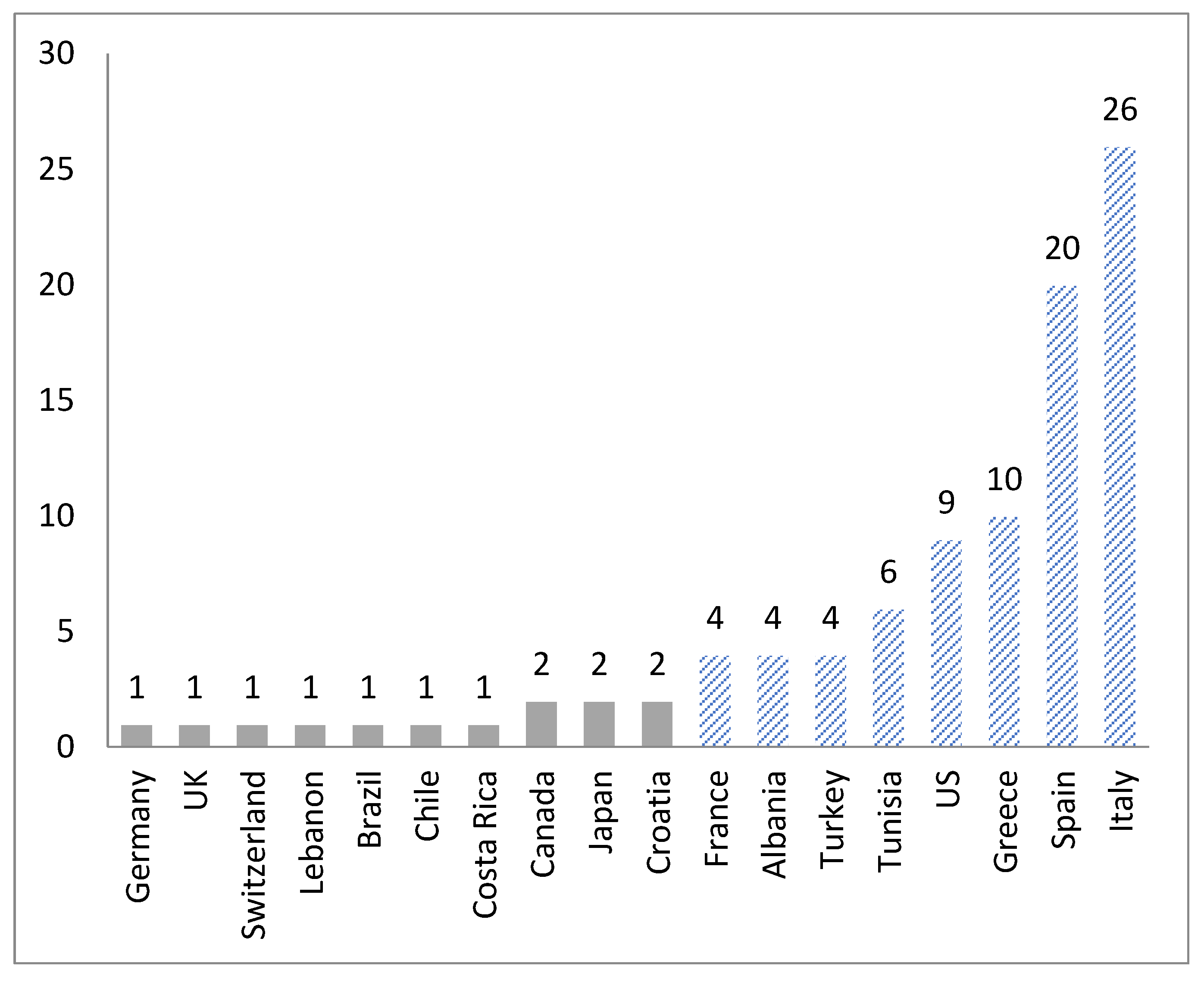

3.2. Overview of the Publications

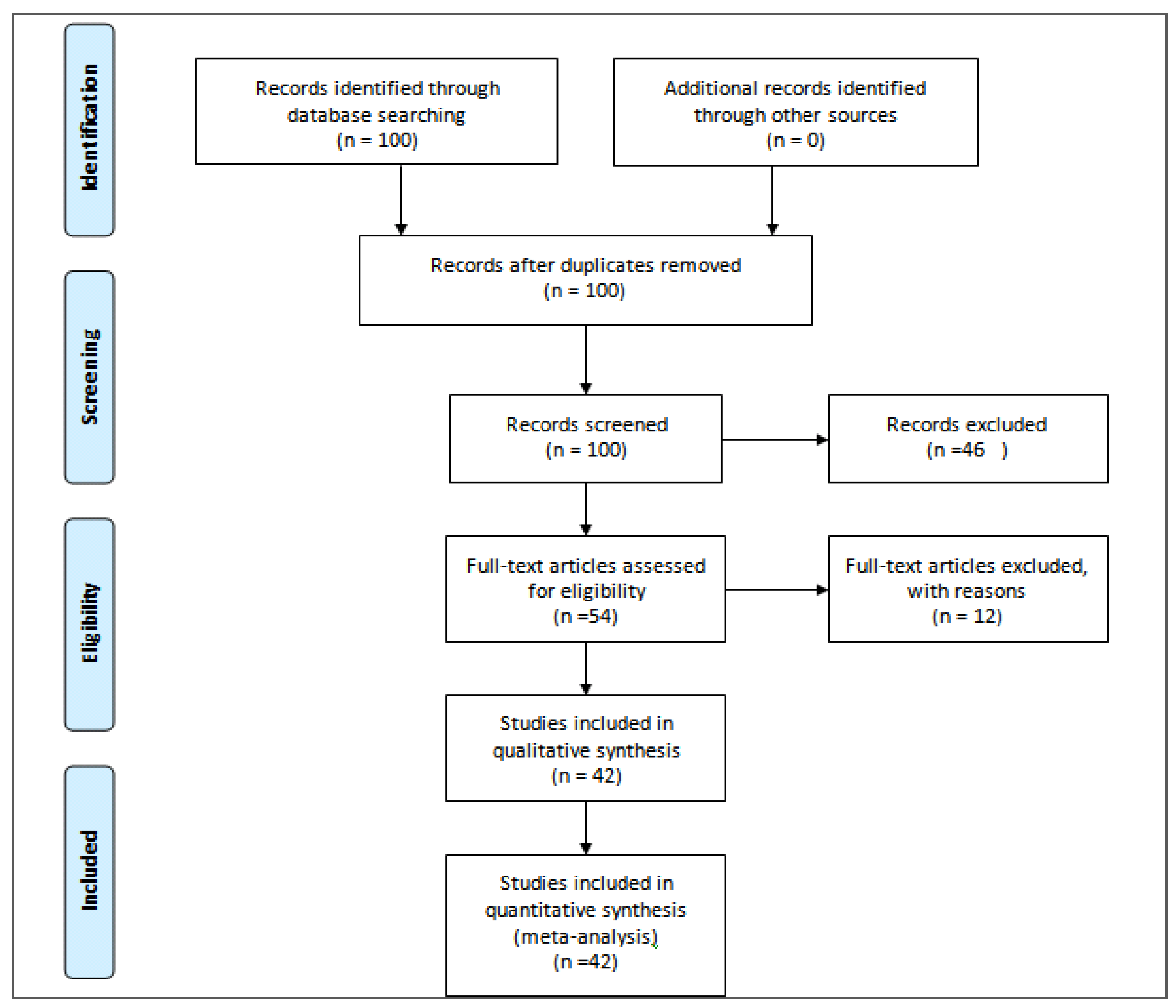

3.3. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA)

- -

- The paper presents a result of an empirical study (literature reviews are excluded);

- -

- The objective of the study deals with aspects related to consumer attitudes and behavior (perception, preferences, buying and consuming habits, etc.).

- -

- The empirical work is a consumer study (studies with farmers, manufacturers, experts are not considered);

- -

- At least one olive oil sustainability label is studied;

4. Results

4.1. Consumer Attitudes and Behavior Regarding Origin-Based Labeling on Olive Oil

4.1.1. Country-of-Origin Labeling (COOL)

4.1.2. Region of Origin’ Labeling

4.1.3. Consumers Attitudes and Behavior Regarding ‘Local’ Labeling on Olive Oil

4.2. Consumers Attitudes and Behavior Regarding Environmental Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil

4.3. Consumers Attitudes and Behavior Regarding Social and Cultural Sustainability Labeling on Olive Oil

4.4. Competition or Complementarities between Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Key Findings

5.2. Consumer Preferences towards Sustainability Labels in the Context of Olive Oil

5.3. Perspectives for Future Research

- -

- Synergies and oppositions between different sustainability labels

- -

- Consumer perceptions of geographical indications transition towards the inclusion of environmental aspects

- -

- Cross-cultural analysis including different territorial context, for olive oil particularly including North/South Mediterranean and producer/non-producer countries

- -

- Consumer behavior in the context of circular economy agenda, acceptance of products issued from waste and by-products

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jurgilevich, A.; Birge, T.; Kentala-Lehtonen, J.; Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Pietikäinen, J.; Saikku, L.; Schösler, H. Transition towards Circular Economy in the Food System. Sustainability 2016, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qaim, M. Globalisation of agrifood systems and sustainable nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodano, V. Innovation and food system sustainability: Public concerns vs. private interests. In Proceedings of the EAAE Seminar ‘System Dynamics and Innovation in Food Networks’, Innsbruck-Igls, Austria, 18–22 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Obi, F.O.; Ugwuishiwu, B.O.; Nwakaire, J.N. Agricultural waste concept, generation, utilization and management. Niger. J. Technol. 2016, 35, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartiu, V.E.; Morone, P. Grassroots Innovations and the Transition Towards Sustainability: Tackling the Food Waste Challenge. In Food Waste Reduction and Valorisation; Morone, P., Papendiek, F., Tartiu, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herrick, J. Unlocking the Potential of Land Resources: Evaluation Systems, Strategies and Tools for Sustainability; A Report of the Working Group on Land and Soils of the International Resource Panel; Herrick, J., Ed.; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya; Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, W.; Roosen, J. Market differentiation potential of country-of-origin, quality and traceability labeling. J. Int. Trade Law Policy 2009, 10, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Sustainable food consumption. Product choice or curtailment? Appetite 2015, 91, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Oosterveer, P.; Lamotte, L.; Brouwer, I.D.; de Haan, S.; Prager, S.D.; Khoury, C.K. When food systems meet sustainability—Current narratives and implications for actions. World Dev. 2019, 113, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D. Extra-virgin olive oil production sustainability in northern Italy: A preliminary study. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1942–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.; Adger, W.N.; Brown, K. Adaptation to environmental change: Contributions of a resilience framework. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2007, 32, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomez-Limon, J.; Sanchez-Fernandez, G. Empirical evaluation of agricultural sustainability using composite indicators. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, M.G.; van den Bosch, H.; Diemont, H.; van Keulen, H.; Lahr, J.; Meijerink, G.; Verhagen, A. Quantifying the sustainability of agriculture. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2007, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banterle, A.; Cereda, E.; Fritz, M. Labelling and sustainability in food supply. Br. Food J. 2013, 37, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Partidario, M.R.; Sheate, W.R.; Bina, O.; Byron, H.; Augusto, B. Sustainability assessment for agriculture scenarios in Europe’s mountain areas: Lessons from six study areas. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandecandelaere, E.; Arfini, F.; Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A. Linking People, Places and Products. A Guide for Promoting Quality Linked to Geographical Origin and Sustainable Geographical Indications; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1760e/i1760e00.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2017).

- Popovic, I.; Bossink, B.A.G.; van der Sijde, P.C. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Decision to Purchase Food in Environmentally Friendly Packaging: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go from Here? Sustainability 2019, 11, 7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erraach, Y.; Sayadi, S.; Parra-Lopez, C. Measuring preferences and willingness to pay for sustainability labels in olive oil: Evidence from Spanish consumers. In Proceedings of the XV EAAE Congress, Parma, Italy, 29 August–1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bangsa, A.B.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. Linking sustainable product attributes and consumer decision-making: Insights from a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfini, F.; Bellassen, V. (Eds.) Sustainability of European Food Quality Schemes: Multi-Performance, Structure, and Governance of PDO, PGI, and Organic Agri-Food Systems; Springer Nature: Basel, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sidali, K.L.; Spiler, A.; von Meyer-Hofer, M. Consumer expectations regarding sustainable food: Insights from developed and emerging markets. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Magistris, T.; Gracia, A. Consumers’ willingness to pay for light, organic and PDO cheese. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnevehr, L.; Eales, J.; Jensen, H.; Lusk, J.; McCluskey, J.; Kinsey, J. Food and consumer economics. American. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 92, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattie, K. Golden goose or wild goose? The hunt for the green consumer. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsos and London Economics Consortium Report. Consumer Market Study on the Functioning of Voluntary Food Labelling Schemes for Consumers in the European Union EAHC/FWC/2012 86 04. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-labelling-scheme-final-report_en.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Erraach, Y.; Sayadi, S.; Parra-López, C. Olive oil origin preferences: Incidence of socio-economic variables and lifetyle. In Vilar Hernández J. (Coord.), The Olive Oil Producing Sector: A Multidisciplinary Study; Centro Internacional de Excelencia para Aceite de Oliva–GEA Westfalia Separator Ibérica, S.A.: Granollers, Spain, 2013; pp. 473–494. ISBN 978-84-616-3992-2. [Google Scholar]

- Allaire, G. Diversité des Indications Géographiques et positionnement dans le nouveau régime de commerce international. Cah. Options. Mediterr. 2009, 89, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, U. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Agri-food Chains: A Competitive Factor for Food Exporters. In Bhat R. (coord.), Sustainability Challenges in the Agrofood Sector; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 150–174. ISBN 9781119072768. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.A.; Jolibert, A.J.P. A meta-analysis of country-of-origin effects. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1995, 26, 883–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, A. A Comparison of Japanese and U.S. Attitudes toward foreign products. J. Mark. 1970, 34, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.M. Country image: Halo or summary construct. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.K.; Ronkainen, I.A.; Czinkota, M. Negative Country of Origin Effects: The case of new Russia. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1994, 25, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Chen, C.I.; Sher, P.J. Investigation on perceived country image of imported food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Ward, R.W. Consumer interest in information cues denoting quality, traceability and origin: An application of ordered probit models to beef labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S.; Lobb, A.; Butler, L.; Harvey, K.; Bruce Traill, W. Local, national and imported foods: A qualitative study. Appetite 2007, 49, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicia, G.; Cembalo, L.; Del Giudice, T.; Scarpa, R. The impact of country-of-origin information on consumer perception of environment-friendly characteristics. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cicia, G.; Cembalo, L.; Del Giudice, T. Country-of-origin effects on German peaches consumers. New. Medit. 2012, 11, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.M.; Terpstra, V. Country of origin effects for Uni-National and Bi-National products. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988, 28, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font i Furnols, M.; Realini, C.; Montossi, F.; Sañudo, C.; Campo, M.M.; Oliver, M.A.; Nute, G.R.; Guerrero, L. Consumer’s purchasing intention for lamb meat affected by country of origin, feeding system and meat price: A conjoint study in Spain, France and United Kingdom. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lans, I.; van Ittersum, K.; De Cicco, A.; Loseby, M. The role of origin and EU certificates of origin in consumer evaluation of food products. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001, 28, 451–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaďuďová, J.; Marková, I.; Hroncová, E.; Vicianová, J.H. An Assessment of Regional Sustainability through Quality Labels for Small Farmers’ Products: A Slovak Case Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorenz, B.; Hartmann, M.; Simons, J. Impacts from region-of-origin labeling on consumer product perception and purchasing intention–causal relationships in a TPB based model. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 45, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Ittersum, K.; Meulenberg, M.T.; Van Trijp, H.C.; Candel, M.J. ‘Consumers’ Appreciation of Regional Certification Labels: A Pan-European Study. J. Agric. Econ. 2007, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions and preferences for local food: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pícha, K.; Navrátil, J.; Švec, R. Preference to Local Food vs. Preference to “National” and Regional Food. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, P.; Toth, Z.B.; Fehér, O. The economic and marketing importance of local food products in the business policy of a Hungarian food retail chain. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 81, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearson, D.; Henryks, J.; Trott, A.; Jones, P.; Parker, G.; Dumaresq, D.; Dyball, R. Local food: Understanding consumer motivations in innovative retail formats. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneed, C.T. Local Food Purchasing in the Farmers’ Market Channel: Value-Attitude Behavior Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cranfield, J.; Henson, S.; Blandon, J. The effect of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on the likelihood of buying locally produced food. Agribus 2012, 28, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onozaka, Y.; McFadden, D.T. Does local labeling complement or compete with other sustainable labels? A conjoint analysis of direct and joint values for fresh produce claim. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 93, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Tong, C. Organic or local? Investigating consumer preference for fresh produce using a choice experiment with real economic incentives. HortScience 2009, 44, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Trajer, N.; Lehberger, M. What is local food? The case of consumer preferences for local food labeling of tomatoes in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 207, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Li, J. Who buys local food? J. Food Distrib. Res. 2006, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, D.; Colasanti, K.; Ross, R.B.; Smalley, S.B. Locally grown foods and farmers markets: Consumer attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability 2010, 2, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCluskey, J.J. A game theoretic approach to organic foods: An analysis of asymmetric information and policy. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2000, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erraach, Y.; Sayadi, S. L’étiquetage environnemental et social: Quel intérêt pour valoriser l’huile d’olive espagnole en France? New Medit 2020, 19, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Ianuario, S.; Pascale, P. Consumers’ attitudes toward labelling of ethical products: The case of organic and fair trade products. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2011, 17, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui-Essoussi, L.; Zahaf, M. Canadian organic food consumers’ profile and their willingness to pay premium prices. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2012, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Paladino, A. Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australas. Mark. J. 2010, 18, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Hamm, U. Consumer preferences for additional ethical attributes of organic food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 5, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanigro, M.; McFadden, D.; Kroll, S.; Nurse, G. An in-store valuation of local and organic apples: The role of social desirability. Agribus. 2011, 27, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmar, U. Consumers’ purchase of organic food products. A matter of convenience and reflexive practices. Appetite 2011, 56, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Magistris, T.; Gracia, A. Do consumers pay attention to the organic label when shopping organic food in Italy? In Organic Food and Agriculture—New Trends and Developments in the Social Sciences; Reed, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 109–208. [Google Scholar]

- Yiridoe, E.K.; Bonti-Ankomah, S.; Martin, R.C. Comparison of consumer’s perception towards organic versus conventionally produced foods: A review and update of the literature. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2005, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Product labelling in the market for organic food: Consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 25, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfkih, S.; Wannessi, O.; Mtimet, N. Le commerce équitable entre principes et réalisations: Le cas du secteur oléicole Tunisien. N. Medit. 2013, 1, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rapp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langen, N. Are ethical consumption and charitable giving substitutes or not? Insights into consumers’ coffee choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Monroe, K.B.; Cox, J.L. The Price is Unfair! A conceptual framework of price fairness perceptions. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpal, F.; Hatchuel, G. La consommation engagée s’affirme comme une tendance durable. Consommation Modes Vie 2007, 201, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.; Johns, N.; Kilburn, D. An exploratory study into the factors impeding ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 98, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Janssens, W. A model of fair trade buying behavior: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75l, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, S.; Ping, Q.; Wuyang, H.; Yun, L. Using a modified payment card survey to measure Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for fair trade coffee: Considering starting points. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 61, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagbata, D.; Sirieix, L. Apports et limites de la double labellisation bio et équitable pour les consommateurs. Econ. Soc. 2008, 42, 2127–2148. [Google Scholar]

- Rousu, M.; Corrigan, J. Estimating the Welfare Loss to Consumers When Food Labels Do Not Adequately Inform: An Application to Fair Trade Certification. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2008, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, T. Are Stated Preferences Confirmed by Purchasing Behaviour? The case of fair trade-certified bananas in Switzerland. J. Bus. Ethics. 2010, 92, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finardi, C.; Giacomini, C.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Consumer preferences for country-of-origin and health claim labelling of extra-virgin olive-oil. In Proceedings of the 113rd EAAE Seminar on: “A Resilient European Food Industry and Food Chain in a Challenging World”, Chania, Greece, 3–6 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zulug, A.; Miran, B.; Tsakiridou, E. Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Country of Origin Labeled Product in Istanbul. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2015, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, D.; Capecchi, S.; Iannario, M.; Corduas, M. Modelling consumer preferences for extra virgin olive oil: The Italian case. Int. J. Agric. Pol. Res. 2013, 1, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mtimet, N.; Ujiie, K.; Kashiwagi, K.; Zaibet, L.; Nagaki, M. The effects of Information and Country of Origin on Japanese Olive Oil Consumer Selection. In Proceedings of the International Congress of European Association of Agricultural Economists, Zurich, Switzerland, 30 August–2 September 2011; European Association of Agricultural Economists: Zurich, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Romo-Muñoz, R.A.; Cabas-Monje, J.H.; Garrido-Henrríquez, H.M.; Gil, J.M. Heterogeneity and nonlinearity in consumers’ preferences: An application to the olive oil shopping behavior in Chile. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dekhili, S.; Sirieix, L.; Cohen, E. How consumers choose olive oil: The importance of origin cues. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, G.; Policastro, S.; Carlucci, A.; Monteleone, E. Consumer expectations for sensory properties in virgin olive oils. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, S.; Guldas, M. An Impact Assessment of Origin Labeling on Table Olive and Olive Oil Demand. Acta Hortic. 2008, 791, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C.; Gómez-Rico, A.; Guinard, J.X. Evaluating bottles and labels versus tasting the oils blind: Effects of packaging and labeling on consumer preferences, purchase intentions and expectations for extra virgin olive oil. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtimet, N.; Zaibet, L.; Zairi, C.; Hzami, H. Marketing olive oil products in the Tunisian local market: The importance of quality attributes and consumers’ behavior. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2013, 25, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, C.; Krystallis, A. Are quality labels a real marketing advantage? A conjoint application on Greek PDO protected olive oil. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2001, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejel, J.; Fandos, C.; Flavián, C. The influence of consumer degree of knowledge on consumer behavior: The Case of Spanish Olive Oil. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2009, 15, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erraach, Y.; Sayadi, S.; Gómez, A.C.; Parra-López, C. Consumer-stated preferences towards Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) labels in a traditional olive oil producing country: The case of Spain. N. Medit. 2014, 13, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Santosa, M.; Guinard, J.X. Means-end chains analysis of extra virgin olive oil purchase and consumption behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Halbrendt, C.; Zhllima, E.; Sisiorc, G.; Imami, D.; Leonettie, L. Consumer preferences for olive oil in Tirana, Albania. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2010, 13, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Muça, E.; Kapaj, A.; Sulo, R.; Hodaj, N. Factors Influencing Albanian Consumer Preferences for Standardized Olive Oil. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2017, 10, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ganideh, S.F.; Good, L.K. Nothing Tastes as Local: Jordanians’ Perceptions of Buying Domestic Olive Oil. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaban, J. The Efficiency of Food Labeling as a Rural Development Policy: The Case of Olive Oil in Lebanon; American University of Beirut: Beirut, Lebanon, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Perito, M.A.; Giampiero, S.; Di Mattia, C.D.; Chiodo, E.; Pittia, P.; Saguy, I.S.; Cohen, E. Buy Local! Familiarity and Preferences for Extra Virgin Olive Oil of Italian Consumers. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 462–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polenzani, B.; Riganelli, C.; Marchini, A. Sustainability Perception of Local Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Consumers’ Attitude: A New Italian Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandalidou, E.; Baourakis, G.; Siskos, Y. Customers’ perspectives on the quality of organic olive oil in Greece. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeras, N.; Valchovska, S.; Baourakis, G.; Kalaitzis, P. Dutch Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Organic Olive Oil. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2009, 21, 286–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberatore, L.; Casolani, N.; Murmura, F. What’s behind organic certification of extra-virgin olive oil? A response from Italian consumers. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ruiz, F.J.; Vega-Zamora, M.; Parras-Rosa, M. False Barriers in the Purchase of Organic Foods. The Case of Extra Virgin Olive Oil in Spain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menegaki, A.; Hanley, N.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Social acceptability and evaluation of recycled water in Crete: A study of consumers’ and farmers’ attitudes. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 62, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, T.; Kashiwagi, K.; Isoda, H. Effect of Religious and Cultural Information of Olive Oil on Consumer Behavior: Evidence from Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Gastaldi, M.; Morone, P. A Social Analysis of the Olive Oil Sector: The Role of Family Business. Resources 2019, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Vita, G.; D’Amico, M.; La Via, G.; Caniglia, E. Quality perception of PDO extra-virgin olive oil: Which attributes most influence Italian consumer. Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 14, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Markovina, J.; Caputo, V. The Impact of Product Designations on Consumer Decisions: The Case of Croatian Olive Oil. Bus. Rev. Camb. 2010, 15, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Panico, T.; Caracciolo, F.; Del Giudice, T. Quality dimensions and consumer preferences: A choice experiment in the Italian extra-virgin olive oil market. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2014, 15, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Liberatore, L.; Casolani, N.; Murmura, F. Perception of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Certifi-cations: A Commodity Market Perspective. Izvestiya. Varna Univ. Econ. Engl. Online 2017, 61, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chousou, C.; Tsakiridou, E.; Mattas, K. Valuing Consumer Perceptions of Olive Oil Authenticity. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2018, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, L.; Carlucci, D.; Gennaro, B.C. What Is the Value of Extrinsic Olive Oil Cues in Emerging Markets? Empirical Evidence from the U.S. E-Commerce Retail Market. Agribus 2017, 32, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, R.; Del Giudice, T. Market Segmentation via Mixed Logit: Extra-Virgin Olive Oil in Urban Italy. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2004, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menapace, L.; Colson, G.; Grebitus, C.; Facendola, M. Consumers’ preferences for geographical origin labels: Evidence from the Canadian olive oil market. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 38, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, G.; Carlucci, D.; Sardaro, R. Assessing consumer preferences for organic vs eco-labelled olive oils. Org. Agric. 2019, 9, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato, D. Analysis of the Factors that Influence Olive Oil Demand in the Veneto Region. Agriculture 2019, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krystallis, A.; Ness, M. Consumer preferences for quality foods from a South European perspective: A conjoint analysis implementation on Greek olive oil. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2005, 8, 62–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yangui, A.; Costa-Font, M.; Gil, J.M. The effect of personality traits on consumers’ preferences for extra virgin olive oil. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 51, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavallo, C.; Piqueras-Fiszman, B. Visual elements of packaging shaping healthiness evaluations of consumers: The case of olive oil. J. Sens. Stud. 2017, 32, e12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaczorowska, J.; Rejman, K.; Halicka, E.; Prandota, A. Influence of B2C sustainability labels on purchasing behavior of the Polish consumers on the olive oil market. Olszt. Econ. J. 2019, 14, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Union. Rural Development in the European Union. Statistical and Economic Information Report 2011; Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Paper on Agricultural Product Quality: Product Standards; Farming Requirements and Quality Schemes, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, M.C. Protected designation of origin: An instrument of consumer protection? The case of Parma Ham. Prog. Nutr. 2012, 14, 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Broude, T. Taking ‘Trade and Culture’ Seriously: Geographical Indications and Cultural Protection in WTO Law. J. Int. Econ. Law 2005, 26, 624–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaczorowska, J.; Prandota, A.; Rejman, K.; Halicka, E.; Tul-Krzyszczuk, A. Certification Labels in Shaping Perception of Food Quality—Insights from Polish and Belgian Urban Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Verhoef, P.C. Drivers of and barriers to organic purchase behavior. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Delanchy, M.; Remaud, H.; Zepeda, L.; Gurviez, P. Consumers’ perceptions of individual and combined sustainable food labels: A UK pilot investigation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovic, S.; Magnusson, P.; Stanley, S. Dimensions of fifit between a brand and a social cause and their inflfluence on attitudes. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescotti, A.; Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Edelmann, H.; Belletti, G.; Broscha, K.; Altenbuchner, C.; Scaramuzzi, S. Are Protected Geographical Indications Evolving Due to Environmentally Related Justifications? An Analysis of Amendments in the Fruit and Vegetable Sector in the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A.; Sanz-Cañada, J.; Vakoufaris, H. Linking protection of geographical indications to the environment: Evidence from the European Union olive-oil sector. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Sub-Category | Denominations | Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin-based labeling (economic, social sustainability dimension) | Country | ‘Country of origin’, ‘origin’, ‘place of origin’ or ‘place of provenance’ | The country where the product comes from | |

| Region | Certified label | Protected Designation of Origin “PDO” | Identifies a product that originates from a particular place, region or country, the quality or characteristics of which are mainly due to a particular geographical environment with its inherent natural factors (raw materials, environmental conditions, location) and human factors (traditional and craft production) and the production, transformation and elaboration stages of which all take place with inside the described geographical area, in respect of consistent production regulations established in the procedural guidelines of production | |

| Protected Geographical Indication “PGI” | Indicates a product that originates from a particular place, region or country, whose given quality and characteristics are basically related to its geographical origin, and for which at least one of the production steps takes place with inside the described geographical area | |||

| Not certified label | The name of region of origin | It consists on indicating the region where product was made it. | ||

| Local | ‘Farm to fork’, ‘short supply chain’, ‘traditional product’ | A variable geographical indication that depends on the consumer perception of the term ‘local’, it can be a country, a region, a village. | ||

| Environmental sustainability | Eco-label | Environmental labels | A quality label indicating that the product was produced with less harmful effects on the environment. | |

| Organic agriculture | Organic farming, organic production, Bio | A production system that follows specific regulations to guarantee the sustainability of the soil, ecosystem and human. | ||

| Social and cultural sustainability | Fair-trade | A certification system that guarantees social sustainability (restrict child labor, guaranteeing a safe workplace and the right to unionize), economic sustainability (fair price that covers the cost of production and facilitates social development, and environmental sustainability (conservation of the environment). | ||

| Number of Databases | Language | Database |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | English | AgEcon, Web of science, EconPapers, NAL Catalog, Google Scholar, Emerald insight, Taylor and Francis online, Science Direct |

| Authors | Country | Region | Purpose of the Studies | Type of Label or Sustainability Aspect | The Aspect Studied | Methods Used in the Studies | Sample Size | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finardi et al. (2009) | Italy | Not specified | Analyze the introduction of country-of-origin labeling and new health claims | Local product | consumer preferences | Focus group, Questionnaire, choice experiment | 196 | The attribute related to the Italian origin carried the highest parameter relative to the other attributes, health claim and acidity level information. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erraach, Y.; Jaafer, F.; Radić, I.; Donner, M. Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil: A Review on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112310

Erraach Y, Jaafer F, Radić I, Donner M. Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil: A Review on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112310

Chicago/Turabian StyleErraach, Yamna, Fatma Jaafer, Ivana Radić, and Mechthild Donner. 2021. "Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil: A Review on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112310

APA StyleErraach, Y., Jaafer, F., Radić, I., & Donner, M. (2021). Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil: A Review on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior. Sustainability, 13(21), 12310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112310