The Impact of CSR on Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Second-Order Social Capital

Abstract

:1. Introduction

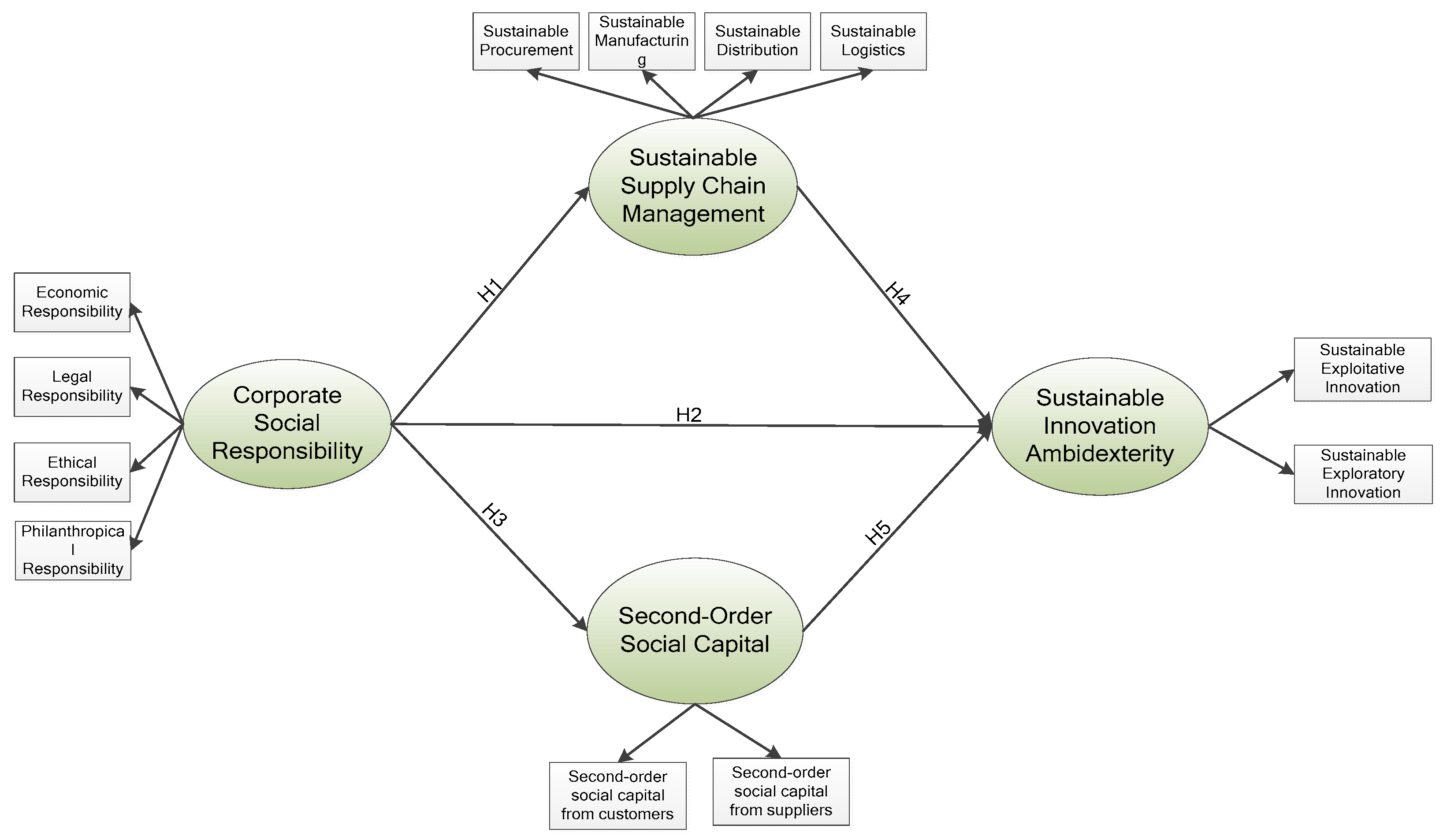

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. CSR and Sustainable Supply Chain Management

2.2. CSR and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity

2.3. CSR and Second-Order Social Capital

2.4. Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity

2.5. Second-Order Social Capital and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity

2.6. The Mediating Role of Second-Order Social Capital

2.7. The Mediating Role of Sustainable Supply Chain Management

3. Methodology

Sample and Procedure

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Data Analysis

4.2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

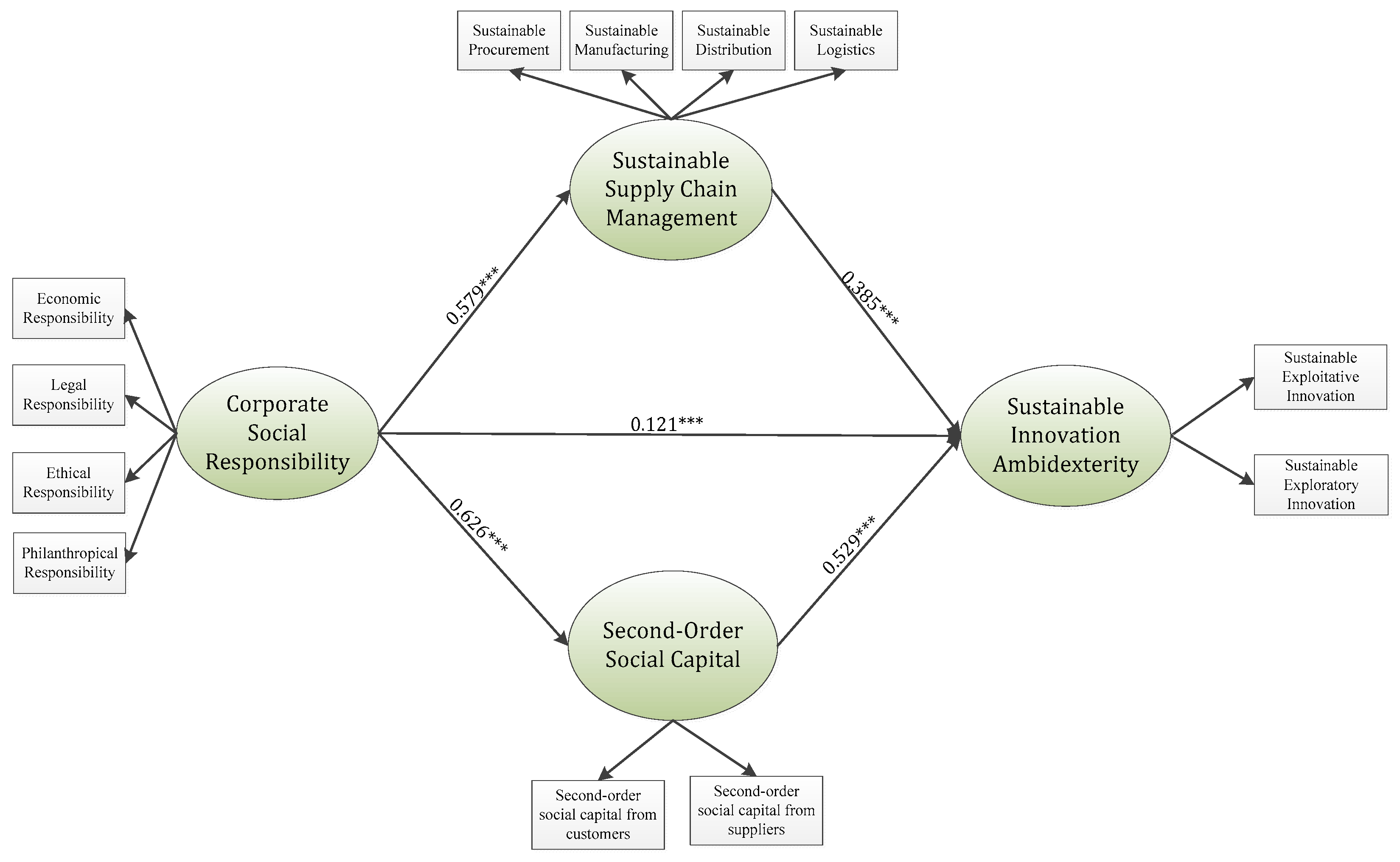

4.3. Empirical Results

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

7. Theoretical Implications

8. Managerial Implications

9. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Economic CSR

- ECO 1:

- The organization improves the business industry.

- ECO 2:

- The organization generates employment through their operations.

- ECO 3:

- The organization strives to activate the local economy.

- ECO 4:

- The organization strives to achieve sustainable growth.

- Legal CSR

- LEG 1:

- The organization properly implements health and safety rules and regulations.

- LEG 2:

- The organization has established appropriate regulations for customers to abide by.

- LEG 3:

- The organization strives to abide by regulations related to their customers well-being.

- Ethical CSR

- ETHI 1:

- The organization has established ethical guidelines for business activities.

- ETHI 2:

- The organization tries to become an ethically trustworthy company.

- ETHI 3:

- The organization makes efforts to fairly treat customers.

- Philanthropic CSR

- PHI 1:

- The organization participates in a variety of volunteer activities by starting the company’s volunteer group.

- PHI 2:

- The organization supports social welfare projects for the underprivileged.

- PHI 3:

- The organization supports education programs.

- Second-Order Social Capital from Customers

- SOCC 1:

- Our major customers have many direct relationships with their partners.

- SOCC 2:

- The relationship between the partners of our main customer shall be established mainly through our customer.

- SOCC 3:

- Our primary customers are more closely related to other members of the industry than to its competitors in the same industry.

- SOCC 4:

- Our main customers have a closer relationship with a university or research institute than its peers.

- SOCC 5:

- Most peer companies of our major customers know the technical capabilities and products of our major customers.

- SOCC 6:

- Our main customers are intermediaries for technical exchanges between other enterprises in the same industry.

- SOCC 7:

- Peer companies of our major customers expect our major customers to provide new knowledge or technologies when they need technical advice.

- SOCC 8:

- The change of business behavior or strategy of our major customers has a great impact on other companies in the same industry.

- Second-Order Social Capital from Suppliers

- SOSS 1:

- Our major suppliers have many direct contacts with their partners.

- SOSS 2:

- The relationship between the partners of our main suppliers shall be established mainly through our suppliers.

- SOSS 3:

- Our primary suppliers are more closely related to other members of the industry than to its competitors in the same industry.

- SOSS 4:

- Our main suppliers have a closer relationship with a university or research institute than its peers.

- SOSS 5:

- Most peer companies of our major suppliers know the technical capabilities and products of our major suppliers.

- SOSS 6:

- Our main suppliers are intermediaries for technical exchanges between other enterprises in the same industry.

- SOSS 7:

- Peer companies of our major suppliers expect our major suppliers to provide new knowledge or technologies when they need technical advice.

- SOSS 8:

- The change of business behavior or strategy of our major suppliers has a great impact on other companies in the same industry.

- Sustainable Exploitative Innovation

- SET 1:

- We usually strive to improve the environmental quality of our existing products (services).

- SET 2:

- We always strive to provide more and better supporting services for existing green and environment-friendly products.

- SET 3:

- We often try to reduce the production cost of existing products (services) by choosing low energy consuming materials.

- SET 4:

- We often try to refine the types of green products (services) available.

- Sustainable Exploratory Innovation

- SEP 1:

- We often try to improve the quality of the existing green products.

- SEP 2:

- We often try to create or introduce new green products (services).

- SEP 3:

- We often try to introduce new environmental protection technology.

- SEP 4:

- We often try to develop new green products (services) into emerging markets.

- SEP 5:

- We often try to adjust our product structure to make our products (services) more environmentally friendly.

- SEP 6:

- We often try to improve our business processes to make our products (services) more environmentally friendly.

- Sustainable Procurement

- SP 1:

- We follow the principles of the 3Rs: reuse, recycle, and reduce in the process of green procurement in terms of paper and parts container (plastic bag/box).

- SP 2:

- We place purchase orders through email (paperless).

- SP 3:

- We use eco-labeling on our products.

- SP 4:

- We ensure our suppliers’ environmental compliance certifications.

- SP 5:

- We conduct auditing for suppliers’ internal environmental management.

- Sustainable Manufacturing

- SM 1:

- We as a manufacturer, design products that facilitate the reuse, recycle and recovery of parts and material components.

- SM 2:

- We avoid or reduce the use of hazardous products within the production process.

- SM 3:

- We minimize the consumption of materials as well as energy.

- Sustainable Distribution

- SD 1:

- We use strategies to downsize packaging.

- SD 2:

- We use “green” packaging materials.

- SD 3:

- We promote recycling and reuse programs.

- SD 4:

- We cooperate with vendors to standardize packaging.

- SD 5:

- We encourage and adopt returnable packaging methods.

- SD 6:

- We minimize material uses and time to unpack.

- SD 7:

- We use recyclable pallet system and lastly.

- SD 8:

- We save energy in warehouses.

- Sustainable Logistics

- SL 1:

- We collect used products and packaging from customers for recycling.

- SL 2:

- We return packaging and products to suppliers for reuse.

- SL 3:

- We require suppliers to collect their packaging materials.

References

- ElAlfy, A.; Palaschuk, N.; El-Bassiouny, D.; Wilson, J.; Weber, O. Scoping the evolution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) research in the sustainable development goals (SDGs) era. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Whiteman, G.; Parker, J.N. Backstage interorganizational collaboration: Corporate endorsement of the sustainable development goals. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2019, 5, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, A.; Weber, O. Corporate Sustainability Reporting The Case of the Banking Industry; CIGI Paper; Centre for International Governance Innovation: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, N.; Chaim, O.; Cazarini, E.; Gerolamo, M. Manufacturing in the fourth industrial revolution: A positive prospect in sustainable manufacturing. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 21, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Rich, N.; Kumar, D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Enablers to implement sustainable initiatives in agri-food supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 203, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Gawankar, S.A. Sustainable Industry 4.0 framework: A systematic literature review identifying the current trends and future perspectives. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Luo, J. Corporate social responsibility as an employee governance tool: Evidence from a quasi-experiment. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domi, S.; Keco, R.; Capelleras, J.-L.; Mehmeti, G. Effects of innovativeness and innovation behavior on tourism SMEs performance: The case of Albania. Econ. Sociol. 2019, 12, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, C.; Rong, D.; Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikis, J. Modified Carroll’s pyramid of corporate social responsibility to enhance organizational performance of SMEs industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Bi, M.; Kuang, H. Design of Evaluation Scheme for Social Responsibility of China’s Transportation Enterprises from the Perspective of Green Supply Chain Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervani, A.A.; Helms, M.M.; Sarkis, J. Performance measurement for green supply chain management. Benchmarking Int. J. 2005, 12, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.-H. Corporate social responsibility for supply chain management: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 158, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Mridha, B.; Pareek, S.; Sarkar, M.; Thangavelu, L. A flexible biofuel and bioenergy production system with transportation disruption under a sustainable supply chain network. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reefke, H.; Sundaram, D. Key themes and research opportunities in sustainable supply chain management–identification and evaluation. Omega 2017, 66, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, A.; Chen, C.-C.; Lu, K.-H.; Wibowo, A.; Chen, S.-C.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Supply Chain Ambidexterity and Green SCM: Moderating Role of Network Capabilities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, L.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Dezi, L.; Castellano, S. The influence of inbound open innovation on ambidexterity performance: Does it pay to source knowledge from supply chain stakeholders? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Thieme, J. The role of suppliers in market intelligence gathering for radical and incremental innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2009, 26, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunlap, D.; Parente, R.; Geleilate, J.-M.; Marion, T.J. Organizing for innovation ambidexterity in emerging markets: Taking advantage of supplier involvement and foreignness. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2016, 23, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.E.; McDonough III, E.F.; Yang, J.; Wang, C. Aligning knowledge assets for exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity: A study of companies in high-tech parks in China. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Chen, L.-R.; Hung, C.-Y. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Supporting Second-Order Social Capital and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galunic, C.; Ertug, G.; Gargiulo, M. The positive externalities of social capital: Benefiting from senior brokers. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, T.; Shi, H. External involvement and green product innovation: The moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Feng, T. Does second-order social capital matter to green innovation? The moderating role of governance ambidexterity. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seman, N.A.A.; Govindan, K.; Mardani, A.; Zakuan, N.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Hooker, R.E.; Ozkul, S. The mediating effect of green innovation on the relationship between green supply chain management and environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.W. Integrating suppliers into green product innovation development: An empirical case study in the semiconductor industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, T.-Y.; Chan, H.K.; Lettice, F.; Chung, S.H. The influence of greening the suppliers and green innovation on environmental performance and competitive advantage in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. Social capital, innovation and economic growth. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2018, 73, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akçomak, I.S.; Ter Weel, B. Social capital, innovation and growth: Evidence from Europe. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2009, 53, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dovey, K. The role of trust in innovation. Learn. Organ. 2009, 16, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siddique, H.M.A.; Kiani, A.K. Industrial pollution and human health: Evidence from middle-income countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 12439–12448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.T.; Shahab, S.; Hafeez, M. Energy capacity, industrial production, and the environment: An empirical analysis from Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 4830–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Badulescu, A.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Badulescu, D. What Prompts Small and Medium Enterprises to Implement CSR? A Qualitative Insight from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The four faces of corporate citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 1998, 100, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R.; He, Q.; Black, A.; Ghobadian, A.; Gallear, D. Environmental regulations, innovation and firm performance: A revisit of the Porter hypothesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, X.; Yang, S.; Shi, X. How Corporate Social Responsibility and External Stakeholder Concerns Affect Green Supply Chain Cooperation among Manufacturers: An Interpretive Structural Modeling Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Christopher, M.; Creazza, A. Aligning product design with the supply chain: A case study. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, U.R.; Espindola, L.S.; da Silva, I.R.; da Silva, I.N.; Rocha, H.M. A systematic literature review on green supply chain management: Research implications and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y. Drivers and barriers of extended supply chain practices for energy saving and emission reduction among Chinese manufacturers. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Jha, S.K.; Prakash, A. Green manufacturing (GM) performance measures: An empirical investigation from Indian MSMEs. Int. J. Res. Advent Technol. 2014, 2, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Thurner, T.W.; Roud, V. Greening strategies in Russia’s manufacturing–from compliance to opportunity. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2851–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. Greening of the supply chain: An empirical study for SMES in the Philippine context. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2007, 1, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G. Aspects of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM): Conceptual framework and empirical example. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2007, 12, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.-D.; Tsai, F.M.; Tseng, M.-L.; Tan, R.R.; Yu, K.D.S.; Lim, M.K. Sustainable supply chain management towards disruption and organizational ambidexterity: A data driven analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 373–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hock, R.; Erasmus, I. From reversed logistics to green supply chains. Logist. Solut. 2000, 2, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.R.; Poist, R.F. Socially responsible logistics: An exploratory study. Transp. J. 2002, 41, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Poist, R.F. Evolution of conceptual approaches to the design of logistics systems: A sequel. Transp. J. 1989, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, P.-Y.; Lee, V.-H.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. A gateway to realising sustainability performance via green supply chain management practices: A PLS–ANN approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 107, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.; Bon, A.T. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabion, L.; Khorraminia, M.; Andjomshoaa, A.; Ghafouri-Azar, M.; Molavi, H. A new model for assessing the impact of the urban intelligent transportation system, farmers’ knowledge and business processes on the success of green supply chain management system for urban distribution of agricultural products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.-P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W. Corporate social responsibility, Green supply chain management and firm performance: The moderating role of big-data analytics capability. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 37, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.H.; Yang, H.; Lee, M.; Park, S. The impact of institutional pressures on green supply chain management and firm performance: Top management roles and social capital. Sustainability 2017, 9, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thong, K.-C.; Wong, W.-P. Pathways for sustainable supply chain performance—Evidence from a developing country, Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pekovic, S.; Vogt, S. The fit between corporate social responsibility and corporate governance: The impact on a firm’s financial performance. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 103, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Chen, F.; Jones, P.; Xia, S. The effect of institutional investors’ distraction on firms’ corporate social responsibility engagement: Evidence from China. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 1645–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate social responsibility and environmental performance: The mediating role of environmental strategy and green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 160, 120262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdeano-Gómez, E.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Pérez-Mesa, J.C. Sustainability dimensions related to agricultural-based development: The experience of 50 years of intensive farming in Almería (Spain). Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2013, 11, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Leal-Millán, A.; Cepeda-Carrión, G. The antecedents of green innovation performance: A model of learning and capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4912–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerva, M.C.; Triguero-Cano, Á.; Córcoles, D. Drivers of green and non-green innovation: Empirical evidence in Low-Tech SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 68, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Success factors for environmentally sustainable product innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C.; Kraus, S.; Kailer, N.; Baldwin, B. Responsible entrepreneurship: Outlining the contingencies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melay, I.; O’Dwyer, M.; Kraus, S.; Gast, J. Green entrepreneurship in SMEs: A configuration approach. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2017, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, S.O.; Dragu, I.-M.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Farcas, T.V. From CSR and sustainability to integrated reporting. Int. J. Soc. Entrep. Innov. 2016, 4, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Kratzer, J. Social entrepreneurship, social networks and social value creation: A quantitative analysis among social entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2013, 5, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Klassen, R.D. Drivers and enablers that foster environmental management capabilities in small-and medium-sized suppliers in supply chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2008, 17, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Montiel, I. The Adoption of ISO 14001 within the Supply Chain: When Are Customer Pressures Effective? 2007. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/85j5v17p (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Vveinhardt, J.; Andriukaitiene, R.; Cunha, L.M. Social capital as a cause and consequence of corporate social responsibility. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2014, 13, 483–505. [Google Scholar]

- González-Benito, J.; González-Benito, Ó. The role of stakeholder pressure and managerial values in the implementation of environmental logistics practices. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2006, 44, 1353–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.M.; Romis, M. Improving work conditions in a global supply chain. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 48, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.M.; Steg, L.; Koning, M.A. Customers’ values, beliefs on sustainable corporate performance, and buying behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, S.; Jhony, O. Corporate Social Responsibility supports the construction of a strong social capital in the mining context: Evidence from Peru. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. Greening the supply chain: A new initiative in South East Asia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: The mediation role of green innovation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Amran, A.; Jumadi, H. Green innovation adoption among logistics service providers in Malaysia: An exploratory study on the managers’ perceptions. Int. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R.; Kraslawski, A. Creativity enables sustainable development: Supplier engagement as a boundary condition for the positive effect on green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-E.; Liu, C.-H. Impacts of social capital and knowledge acquisition on service innovation: An integrated empirical analysis of the role of shared values. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Yang, S.; Dooley, K. A theory of supplier network-based innovation value. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2017, 23, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfi, W.B.; Hikkerova, L.; Sahut, J.-M. External knowledge sources, green innovation and performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Du, W.; Wu, H.; Wang, J. Effects of environmental regulation and FDI on urban innovation in China: A spatial Durbin econometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Un, C.A.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Asakawa, K. R&D collaborations and product innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2010, 27, 673–689. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saeed, M.M.; Arshad, F. Corporate social responsibility as a source of competitive advantage: The mediating role of social capital and reputational capital. J. Database Mark. Cust. Strategy Manag. 2012, 19, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon, J. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, T. Corporate citizenship: Creating social capacity in developing countries. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlauf, S.; Fafchamps, M. Chapter 26—Social Capital. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Aghion, P., Durlauf, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, I.; Kobeissi, N.; Liu, L.; Wang, H. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance: The mediating role of productivity. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zailani, S.; Govindan, K.; Iranmanesh, M.; Shaharudin, M.R.; Chong, Y.S. Green innovation adoption in automotive supply chain: The Malaysian case. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, R.; Eichhammer, W. Benchmarking green innovation. Miner. Econ. 2012, 24, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Cox, J. Corporate social responsibility and social capital. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 60, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Kumari, R.; Kumar, N.; Sarkar, B. Reduction of waste and carbon emission through the selection of items with cross-price elasticity of demand to form a sustainable supply chain with preservation technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.S.; Prakash, A.; Saxena, P.; Nigam, A. Sampling: Why and how of it. Indian J. Med. Spec. 2013, 4, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Cluster sampling. BMJ 2014, 348, g1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Zhang, S.; Hong, S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.; Lee, H. Interpretation and application of factor analytic results. In A First Course in Factor Analysis; Comrey, A.L., Lee, H.B., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.L.; Rhou, Y.; Uysal, M.; Kwon, N. An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, S.; Straub, D.; Rai, A. Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofod-Petersen, A.; Cassens, J. Using activity theory to model context awareness. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Modeling and Retrieval of Context, Edinburgh, UK, 31 July–1 August 2005; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Govindan, K.; Zhu, Q. A system dynamics model based on evolutionary game theory for green supply chain management diffusion among Chinese manufacturers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 80, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebanjo, D.; Teh, P.-L.; Ahmed, P.K. The impact of external pressure and sustainable management practices on manufacturing performance and environmental outcomes. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, L.; Choi, T.M.; Sethi, S.P. Green supply chain management in Chinese firms: Innovative measures and the moderating role of quick response technology. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 958–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, P.; O’Toole, T.; Biemans, W. Measuring involvement of a network of customers in NPD. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Ryoo, S.Y.; Jung, M.D. Inter-organizational information systems visibility in buyer–supplier relationships: The case of telecommunication equipment component manufacturing industry. Omega 2011, 39, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Q.; Liu, X.; Ahmad, S.; Fu, P.; Awan, H.M. Comparative analysis of entrepreneurship and franchising: CSR and voluntarism perspective. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2020, 31, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, I. Is the Time Right for Human Rights NGOs to Collaborate with Businesses that Want to Stop Dabbling with ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’and Start Making Social Impact? J. Hum. Rights Pract. 2016, 8, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalova, E.; Studenikin, N.; Starikova, E. Business participation in implementation of socially oriented Sustainable Development Goals in countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus region. Cent. Asia Cauc. 2018, 19, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhalim, K.; Eldin, A.G. Can CSR help achieve sustainable development? Applying a new assessment model to CSR cases from Egypt. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | CSR | SSCM | SIA | SOSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saeed et al. [88] (2012) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Jha and Cox [96] (2015) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Thompson [29] (2018) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Shahzad et al. [65] (2019) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Seman et al. [26] (2019) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Lu et al. [10] (2020) | ✔ | |||

| Wang et al. [55] (2020) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Khan et al. [16] (2021) | ✔ | |||

| Sarkar et al. [14] (2021) | ✔ | |||

| Huang et al. [38] (2021) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Yadav [97] (2021) | ✔ | |||

| Luo et al. [11] (2021) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Zhao et al. [25] (2021) | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Present Study | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Construct | Item Code | Factor Loading | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic CSR (first order) | Eco1 | 0.749 | 0.882 | 0.653 |

| Eco2 | 0.793 | |||

| Eco3 | 0.871 | |||

| Eco4 | 0.814 | |||

| Legal CSR (first order) | Leg1 | 0.819 | 0.845 | 0.645 |

| Leg2 | 0.776 | |||

| Leg3 | 0.813 | |||

| Ethical CSR (first order) | Ethi1 | 0.834 | 0.824 | 0.615 |

| Ethi2 | 0.876 | |||

| Ethi3 | 0.619 | |||

| Philanthropical CSR (first order) | Phi1 | 0.904 | 0.912 | 0.776 |

| Phi2 | 0.888 | |||

| Phi3 | 0.850 | |||

| Sustainable Procurement (first order) | SP1 | 0.797 | 0.922 | 0.704 |

| SP2 | 0.847 | |||

| SP3 | 0.832 | |||

| SP4 | 0.857 | |||

| SP5 | 0.861 | |||

| Sustainable Manufacturing (first order) | SM1 | 0.846 | 0.899 | 0.748 |

| SM2 | 0.896 | |||

| SM3 | 0.853 | |||

| Sustainable Distribution (first order) | SD1 | 0.688 | 0.908 | 0.555 |

| SD2 | 0.729 | |||

| SD3 | 0.823 | |||

| SD4 | 0.865 | |||

| SD5 | 0.747 | |||

| SD6 | 0.697 | |||

| SD7 | 0.608 | |||

| SD8 | 0.776 | |||

| Sustainable Logistics (first order) | SL1 | 0.901 | 0.931 | 0.818 |

| SL2 | 0.921 | |||

| SL3 | 0.892 | |||

| SEP (Sustainable Exploratory Innovation) (first order) | SEP1 | 0.751 | 0.907 | 0.620 |

| SEP2 | 0.738 | |||

| SEP3 | 0.772 | |||

| SEP4 | 0.845 | |||

| SEP5 | 0.783 | |||

| SEP6 | 0.824 | |||

| SET (Sustainable Exploitative Innovation) (first order) | SET1 | 0.788 | 0.922 | 0.704 |

| SET2 | 0.844 | |||

| SET3 | 0.837 | |||

| SET4 | 0.858 | |||

| SET5 | 0.866 | |||

| SOCC (Second-Order Social Capital from Customers) (first order) | SOCC1 | 0.751 | 0.924 | 0.604 |

| SOCC2 | 0.808 | |||

| SOCC3 | 0.808 | |||

| SOCC4 | 0.839 | |||

| SOCC5 | 0.855 | |||

| SOCC6 | 0.792 | |||

| SOCC7 | 0.696 | |||

| SOCC8 | 0.646 | |||

| SOSS (Second-Order Social Capital from Suppliers) (first order) | SOSS1 | 0.802 | 0.839 | 0.723 |

| SOSS2 | 0.853 | |||

| SOSS3 | 0.881 | |||

| CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) (second order) | ECO | 0.806 | 0.865 | 0.672 |

| LEG | 0.802 | |||

| ETHI | 0.776 | |||

| PHIL | 0.880 | |||

| Sustainable Supply Chain Management (second order) | SP | 0.838 | 0.771 | 0.543 |

| SM | 0.865 | |||

| SD | 0.741 | |||

| SL | 0.904 | |||

| Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity (second order) | SEP | 0.785 | 0.927 | 0.864 |

| SET | 0.838 | |||

| Second-Order Social Capital (second order) | SOCC | 0.774 | 0.881 | 0.663 |

| SOSS | 0.845 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | t-Statistics | p-Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: CSR → SSCM | 0.579 | 11.532 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2: CSR → SIA | 0.121 | 4.214 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3: CSR → SOSC | 0.626 | 11.851 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4: SSCM → SIA | 0.385 | 8.389 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5: SOSC → SIA | 0.529 | 12.857 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | t-Statistics | p-Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6: CSR → SOSC → SIA | 0.330 | 10.188 | 0.001 | Full mediation |

| H7: CSR → SSCM → SIA | 0.223 | 7.020 | 0.000 | Full mediation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, A.; Chen, C.-C.; Suanpong, K.; Ruangkanjanases, A.; Kittikowit, S.; Chen, S.-C. The Impact of CSR on Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Second-Order Social Capital. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112160

Khan A, Chen C-C, Suanpong K, Ruangkanjanases A, Kittikowit S, Chen S-C. The Impact of CSR on Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Second-Order Social Capital. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112160

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Asif, Chih-Cheng Chen, Kwanrat Suanpong, Athapol Ruangkanjanases, Santhaya Kittikowit, and Shih-Chih Chen. 2021. "The Impact of CSR on Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Second-Order Social Capital" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112160

APA StyleKhan, A., Chen, C.-C., Suanpong, K., Ruangkanjanases, A., Kittikowit, S., & Chen, S.-C. (2021). The Impact of CSR on Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Second-Order Social Capital. Sustainability, 13(21), 12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112160