Abstract

In an attempt to enhance democratic governance, sustainable development goals (SDG), and Local Agenda 21 (LA21), the notion of public participation exercise (PPE) presents a range of possibilities. The PPE is observed as a method of solving the constraints faced by public parks in Malaysia, which in general suffer from two main challenges, namely (i) the underutilisation issue of public parks and (ii) the weakness of the present top-down development policy. Consequently, the objective of this study is to develop indicators for PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia. The method implemented in this study is an assessment of the construct, variable, and indicator adapted from Lazarsfeld’s scheme by conducting a document review of the Public Consultation Index (PCI), six sustainability assessment tools, namely LEED-ND, BREEAM, IDP, SITES V2, Green Mark-NRB, and GTI, and literature references. The variables and indicators were tabulated into the respective operational definition of the construct table and variables and measurement table. The findings include the identification of two main constructs, including public participation and public parks. Multiple variables were derived from each construct, including attributes of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia, development stage, method of approach, type of public, and public parks design criteria. Subsequently, this study developed the fundamental basis for the PPE framework in designing public parks in Malaysia, which benefits the local development approach for public parks towards an integrated design framework.

1. Introduction

This research is primarily derived from three core factors encompassing democratic governance, SDG, and LA21. Therefore, the relationship and association between these three factors and their significance to the public participation exercise (PPE) are further discussed.

Malaysia is a federal constitutional monarchy based on democratic parliamentary governance, which encourages citizens to participate and get involved in their public policies to serve the people and meet their needs [1,2]. This type of public policy displays a bottom-up development framework, whereby the involvement of the public and engagement level of the citizens is central and wide-ranging. Manaf [3] stated that increased public participation in government policies and decisions contributes positively to the enhancement of democracy. Hence, in order to emphasise democratic governance in Malaysia, the public is encouraged to have a role in the formulation and implementation of government civil policies.

In many instances, direct public participation in various governmental processes is intrinsically regarded as a means of democratic freedom of expression and procedural justice [4]. Public participation is strongly associated with democratic governance and is seen as a game changer in terms of decision making, shifting from top-down to bottom-up, with more participatory processes involving diversified factors [5,6,7,8,9]. An ideal democratic governance practise is that the public has a right to influence the decisions that affect them or the things they value [10]. By providing opportunities for citizens to participate in decision-making processes, public participation has proven to be a good exercise in strengthening democratic governance and expanding its horizons, as well as in shifting the present top-down framework for policy development to more participatory processes.

Sustainability is defined as “a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, nature of technological development, and institutional reforms are consistent with the needs of the present and the future” [11]. According to the United Nations, sustainability refers to “the growth or development which fulfils the present needs whilst maintaining the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [11,12]. Subsequently, the United Nations General Assembly adopted seventeen sustainable development goals (SDG), with the goal of enhancing the organisational operationalisation and integration of sustainability and, as a result, SDG address current and future stakeholder needs and ensure a better and sustainable future for all, while balancing economic, social, and environmental development [13]. SDG 17 specifically promotes the strengthening of implementation and revitalisation of the global partnership for sustainable development [14]. The discussion of SDG 17 includes eight major themes, including multi-stakeholder partnerships and voluntary commitments, which further elaborates the integration of decision making undertaken by the government, as emphasised in Agenda 21 (Johannesburg Plan of Implementation) [15]. SDG 17 acknowledges the importance of multi-stakeholder partnerships and encourages effective public, public–private, and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of collective action [14].

The Local Agenda 21 (LA21) was introduced in Malaysia in 1999 and the policy includes the involvement of the community and multi-stakeholders [15]. LA21 is a programme designed to forge partnerships between local authorities in Malaysia and the public, in the planning process and in maintaining the surrounding environment in achieving the SDG [16]. LA21 has mandated the encouragement of the local authorities to have dialogues within the community to achieve development and consensus on the LA21 action plan [15]. However, due to a lack of enforcement at higher levels of local government and the fact that implementation is solely dependent on the individual local authority, the implementation of LA21 activities in Malaysia is considered low [16]. Conversely, the LA21 outlined several aims focusing on people-centred development to achieve the sustainable development goals [3,17,18]. Ngah et al. [18] further highlighted that LA21 states that good urban governance demonstrates “people first” and “people-centric” schemes, emphasising the importance of allowing the public to participate in governmental decision-making processes.

Certainly, democratic governance, SDG, and LA21 have strong relationships in demonstrating the importance of the implementation of PPE in Malaysia. The anticipation of the public in various civil policies strengthens the diversity in obtaining a holistic consensus and decision towards the implementation of sustainable development. Volunteerism as a form of participatory action among the public has consequently been a key element of the progress made to date, including social leadership and higher awareness in implementing the doctrine of sustainable living policy. Undoubtedly, PPE holds great potential for Malaysia in contributing effectively to the global agenda towards sustainable development.

Therefore, the research aims to develop a set of variables and indicators in proposing a public participation framework in designing public parks in Malaysia. In relation to that, this paper identified two main research gaps identified in the Malaysia context, which consist of the following: (1) issues concerning the underutilisation of public parks and (2) weaknesses of top-down civil policies.

(1) Despite the presence of well-designed public parks landscapes, the issue of underutilisation of public parks in Malaysian urban areas persists [19,20]. The lack of public participation in Malaysia’s public parks indicates a failure in the design element of the public parks, despite the huge amount spent annually by the federal government [21]. Furthermore, the design factor is also believed to have an impact on the level of acceptance among the public, and the level of interest/engagement with its facilities [21].

(2) Malaysia’s current landscape practise has a poor policy emphasis in responding to the required components of sustainable development, and it is critical to change this current conventional practise in order to adapt to new, more sustainable landscape practises. [21]. The top-down approach has proven to be a failure despite being based on professional estimators and assumptions as opposed to the opinions of the public. This has led to the development of unusable spaces that have failed to meet the needs of the public. In the late 1970s, the top-down approach was used in municipalities that adopted Western-style open space models under the “City Cosmetic Movement”. Further, this caused major failures in most public park designs [22]. Ridings and Chitrakar [23] argued that the frameworks designed for public spaces in traditional cities were no longer appropriate. One of the major negative factors was the lack of direct public input during the establishment of the framework.

2. Literature Review

In order to identify the variables and indicators in PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia, the following sections are reviews of literature focusing on the PPE and public parks design criteria in Malaysia.

3. Public Participation Exercise—PPE

Human participatory development, which emphasises sustainably managing and restoring ecosystems, will have a simultaneous effect on promoting wellbeing whilst reducing negative environmental impacts [24]. The development of human participation in this context is related to public opinion and community decision making, as transparent communication may leverage support for certain policies, based on individual or social rationality, as long as people perceive the policy as appropriate to tackling the problem [24]. While the significant role of the community in promoting the sustainability agenda is readily apparent [25], the term social sustainability is not well defined, due in part to the difficulties in quantitatively measuring factors of social sustainability as compared to economic or environmental sustainability [26].

Sustainable development at the community level is defined as a dynamic process in which communities can anticipate and accommodate the needs of present and future generations by reproducing and balancing the local social, economic, and ecological systems to address global concerns [27]. In general, four main factors influenced social sustainable development, including social equity [17,28], sustainable community [29,30], community resilience [31], and community engagement [27,28,29]; thus, the significance of PPE in responding to social sustainable development is highlighted by community engagement factors.

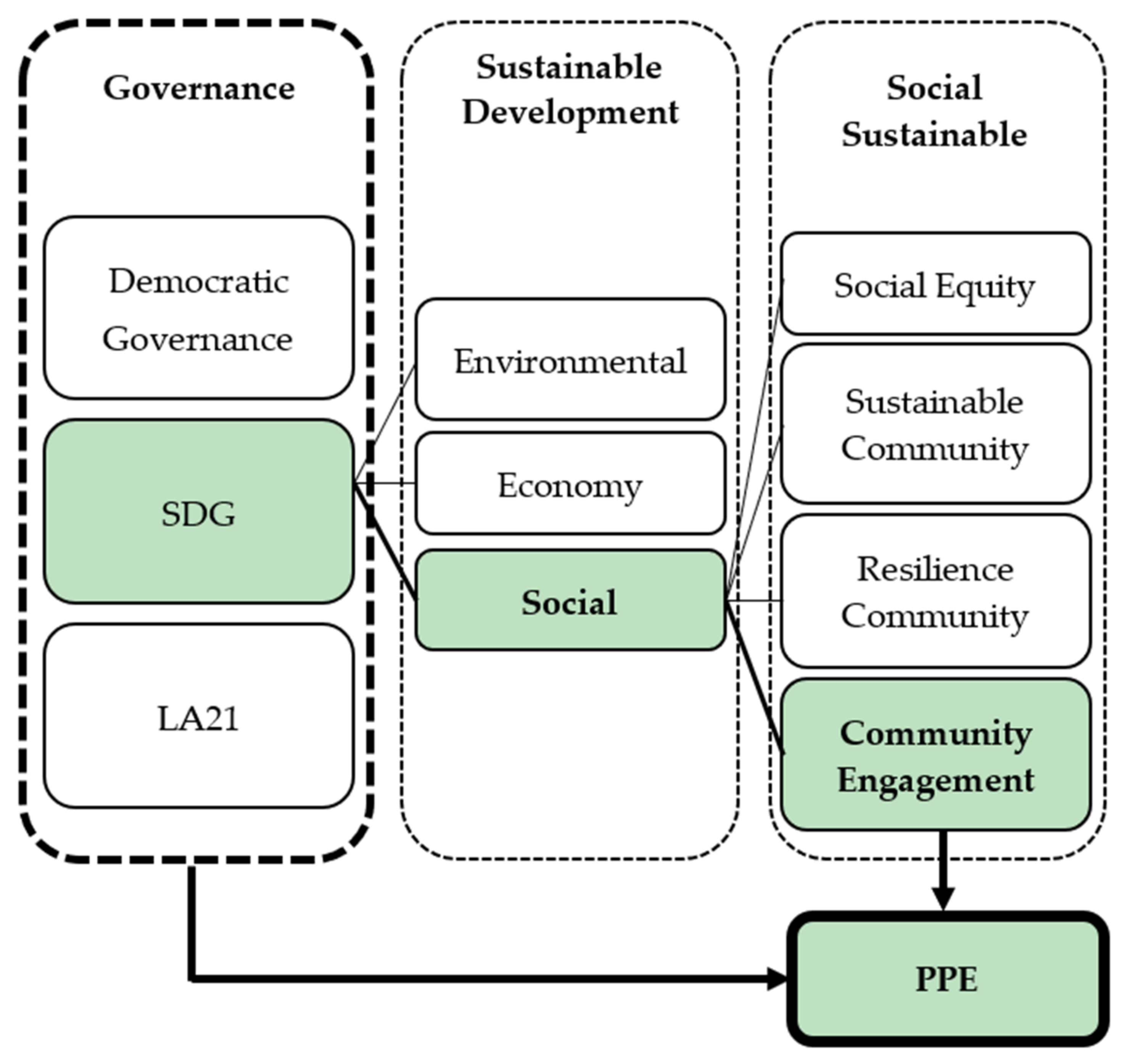

Figure 1 depicts the connection between the governance policy, sustainable development pillars, and the social sustainable factors. PPE is supported at the local governance policy level by the three-governance policy, which comprises democratic governance, SDG, and LA21. The three pillars of sustainable development demonstrate that PPE has a significant effect on social sustainability factors, leading to sustainable development. The concept of community engagement is significant to PPE and emphasises the social sustainability components even more. As a result, PPE is essential to the three criteria mentioned, and this demonstrates the relevance and significance of PPE in Malaysian civil policy implementation.

Figure 1.

The significance of PPE in a Sustainable Development Framework.

PPE is defined as citizen participation and implies the involvement of citizens in a wide range of policymaking activities. These include the determination of levels of service, budget priorities, and the acceptability of physical construction projects in order to orient government programmes toward community needs, build public support, and encourage a sense of cohesiveness within neighbourhoods [32]. There are six concepts in implementing PPE which are labelled as functionalist, neo-liberal, deliberative, anthropological, emancipatory, and post-modern [33]. The concept is explained by the extent of the public contribution expected under the PPE. In general, each PPE is unique, whereby the location, type of public, type of policy, and the objective of PPE are main factors in identifying the characteristics of the framework to be implemented [5,34]. According to Jibladze et al. [34], there are five rising degrees of PPE on the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) spectrum of public involvement. Inform is at the bottom, followed by consult, involve, collaborate, and empower. This spectrum illustrates the substantial degree of public decision-making capacity in PPE implemented by local governments.

The notion of PPE goes beyond just achieving consensus or obtaining mutual understanding in a decision-making context; rather, the PPE itself has considerable benefits to the public in terms of promoting interaction and engagement between the local authority and the citizenry [33]. Furthermore, the PPE is perceived as a pragmatic approach to cope with the complexity of modern societies, given that the public is more informed, educated, and interconnected. Thus, the public is better at accommodating new ideas, different perspectives, and innovative solutions to address issues attended by the local authority [5]. PPE is essential to generate public interest in participating in the local government process, as well as to increase public willingness to play an active role in development planning [33].

PPE has been proven to have a positive effect on public mental wellbeing [35,36,37] and in terms of good design practise in meeting the needs of the end user [38]. Payne et al. [38] highlighted that the implementation of PPE involving the end user should be at the beginning of the design process rather than during the post-occupancy stage, as it is important to ensure that the design meets the needs of the end user. The design brief, which indicates specific design factors during the PPE, is crucial in setting the scope and boundaries of the discussion [38].

It has been suggested that landscape architects integrate with the community in order to include social sustainability factors into the design scheme, as well as in establishing a design and development framework that involves the public [39]. Recent studies on public participation in landscape design have shown that it is superficial and insufficient, thus leading to difficulties in developing a design scheme for public spaces that meets the needs of the people [9].

Based on the current state of sustainable development, the development of an integrated design framework between public and civil policies for public parks is crucial. The role of the public is vital for the development of a design scheme that meets the needs of the public in public spaces. The PPE is an exercise that allows the public to directly contribute towards the decision-making process. Consequently, the PPE in local development projects will increase public awareness and knowledge of sustainable development, as well as motivate the public to care for the development’s long-term upkeep [6,40].

PPE, which is also known as the integrated design process, is an iterative process that is inclusive from the very beginning, front-loaded (with time and commitment being invested from the start), and allows for full optimisation with decisions being influenced by the broader team. It also involves whole-systems thinking, requires life-cycle costing, seeks synergies, and continues throughout post-occupancy. In contrast, the conventional design process is a linear approach that involves team members only when it is essential, requires less time, commitments, and collaboration in the early stages, and involves decisions made by fewer people. Moreover, the systems are often designed in isolation and limited to constrained optimisation processes, have a reduced opportunity for synergies, emphasise up-front costs, and typically finish when the construction is completed [41].

PPE is commonly administered by the local authority [5,34] and in Malaysia, local authorities are mainly classified as city councils, municipal councils and district councils. Each of these local authorities has developed their own development framework as referred to the primary guidelines established by the federal government. The present PPE in Malaysia was established by the Department of Town and Urban Planning (JPBD), known as ‘Publicity’ (SERANTA) for the local development plan in Malaysia, which involves a public exhibition process where local citizens have the opportunity to express their personal opinions to the local authorities during the SERANTA process [42]. According to Ali and Arifin [42], the level of PPE in Malaysia is considered poor and viewed as top-down in the general system instead, whereas it should represent a bottom-up development framework system; thus, PPE in Malaysia at the moment reflects a non-holistic disciplinary approach and is not centralised [42]. Additionally, there is no trace and enforcement of PPE nor SERANTA in landscape departments within local authorities which are responsible for the development of public space projects, including public parks in Malaysia.

Therefore, a further investigation is needed to identify the variables and indicators for PPE by using the Public Consultation Index (PCI) as a main reference. PCI is one of the most referred to in the field of PPE globally [34]. There are six main criteria described in PCI [34] for developing a PPE, which include accessibility, openness, effectiveness of the public consultation process, accountability, diversity of participants, and public engagement/interest.

Table 1 shows that there are five variables identified in an effective public consultation process as referred to PCI. The five main variables are the announcement method, the consultation format, feedback, stages of policy development, and participants.

Table 1.

Extracted Variables of PPE from PCI [34].

Consequently, the discussion on PPE and its relevance has led to the study of public parks in Malaysia. This is due to critical issues confronting the Malaysian public parks, which without a doubt have an impact on society, as the function of public parks in society is more than just a public infrastructure facility, but rather has a substantial impact on the development of sustainable communities. Public parks have proven to be beneficial to the general public’s mental wellbeing and physical health [20]. Therefore, PPE is an important approach to be implemented in designing public parks in Malaysia.

4. Sustainable Assessment’s Tool

This study delves deeper into the independent variable, which was adapted from the six PCI criteria (the announcement method, the consultation format, feedback, stages of policy development, and participant). The sustainable assessment tools are widely used in built-environment research as the assessment tools list a rigorous measurable indicator as a guideline in complimenting sustainable development. According to Siew [43], several green rating tools have been employed to guide the design process and development of buildings, such as the Green Star Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), Building Research Establishment Environment Assessment Method (BREEAM), and Comprehensive Assessment System for Building Environmental Efficiency (CASBEE).

Wu [44,45] recommended the use of several sustainable assessment tools to evaluate both the environmental impact of construction projects and the systems for green development, which include the following: Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA), Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM), Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency (CASBEE), Building Environmental Assessment Method (BEAM), and Sustainable Building Tool (SB Tool). Larco [46] listed several rating scales that were used as sustainability-focused urban scale rating systems, which include LEED-ND, BREEAM communities, STARS, and SITES.

In total, nine sustainable assessment tools were reviewed in identifying the indicator for each variable derived from the PCI. Following this appraisal, out of nine assessment tools, only six of them have relevant indicators to the PPE as follows:

- Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Neighbourhood Development (LEED-ND)—United States [47].

- Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM)—United Kingdom [48].

- Integrated Design Process (IDP)—Canada [49].

- Sustainable Site Initiative SITES v2 Rating System for sustainable land design and development—United States [50].

- Green Mark (For non-residential buildings NRB: 2015)—Singapore [51].

- Green Township Index (GTI)—Malaysia [52].

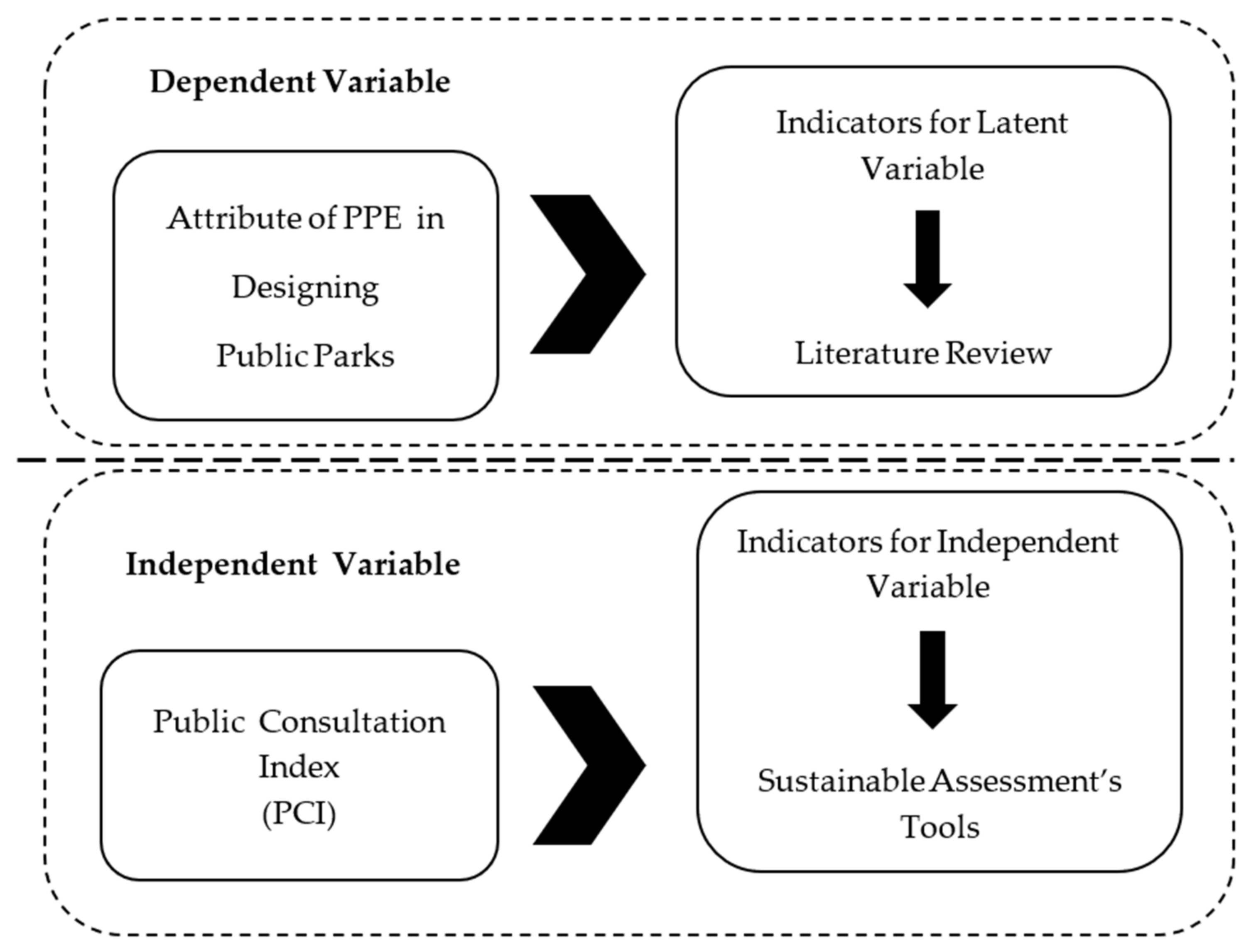

The relevant indicators of PPE are abstracted and tabulated in Lazarsfeld’s scheme method. Figure 2 shows the development of the dependent variable and the independent variable. The dependent variable is derived from the attribute of PPE in designing public parks as shown from the literature references, while the independent variable is developed from the PCI and the indicators are based on the documentation review of six sustainable assessment tools.

Figure 2.

Variables and Indicators of PPE.

5. Public Parks Design in Criteria Malaysia—PPDCM

Adiati [53] stated that parks and green spaces are important components of recreation and relaxation. On the other hand, Ahmad [54] noted that public parks are essentially associated with open spaces and recreation activities. Public parks usually consist of three main components: (1) the parks and their facilities; (2) the landscape; and (3) the architecture of the parks. Sakip [55] emphasised that public parks are an integral aspect of an urban setting. The green spaces within the cities play an important role and provide several health-promoting benefits. In this regard, the public parks’ components, which also include green spaces, potentially have a similar impact on the public [19].

Sakip [55] noted that the public parks categories in Malaysia are based on the Malaysian Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD) Planning Framework for Open Space and Recreation include the following: (1) national parks, (2) regional parks, (3) city parks, (4) local parks, (5) neighbourhood parks, (6) children’s playgrounds, and (7) playgrounds. Ridings and Chitrakar [52] stated that various frameworks designed for public spaces in traditional cities were no longer considered appropriate. One of the major factors is the lack of direct public participation in the establishment of the framework.

Public parks in Malaysia have been developed in urban areas mainly for recreation and relaxation purposes [56], and they have provided significant benefits to the public’s mental wellbeing, and facilities for physical activities [53,57]. Furthermore, Sakip [55] and Ngesan [58] stated that public parks not only offer health benefits to the physical body but also the inter-relationship between the community, and they increase the value of properties. Ridings and Chitrakar [23] stated that a successful public space requires the following components to be embedded: (1) people-friendly urban design factors, (2) human scale, (3) sightliness, (4) activated edges, (5) shelter, (6) seating, (7) engagement, (8) legibility, and (9) permeability. Fu and Ma [59] discussed the significance of PPE and the integration between the community and the local governing system in designing public spaces. Tomlinson [60] highlighted that a successful public space requires the following: (1) places that trigger memories and (2) the cultural and historical meanings of places for individuals and the community.

Ridings and Chitrakar [23] elaborated that people-friendly frameworks were established through various studies by Lynch in 1960, Alexander in 1964, Alexander and Poyner in 1970, Gehl in 1971, Whyte in 1980, Jarvis in 1980, Carr in 1992, Srecnberg in 2000, Tibbalds in 2000, Carmona in 2003, and Crankshaw in 2008. These studies focused on approaches to encourage people to linger in public spaces which were designed for gathering and performing social activities [23]. However, Jan Gehl and Lynch noted that these frameworks do not provide a comprehensive set of rules for the design of public spaces [23].

Fu and Ma [59] argued that the efficient mobilisation of citizens and local governing institutions is required for a sustained interacting mechanism between urban space, social capital, and natural capital. A successful urban space results from a well-functioning community that positively engages with both local authorities and the public. Hence, PPE in decision-making for urban spaces will enhance the quality of urban spaces. Public parks play a crucial role in developing and maintaining the social identities of both individuals and groups [19]. Since public parks are used by various groups of people with diverse backgrounds, the landscape architect is responsible for designing public parks that respond to the needs of the end users. Furthermore, the design of a public park must respond to the local climate and surroundings of the site, historical value, cultural and social influences, as well as security and public safety factors [23].

Brown [61] mentioned that public parks, and in particular community parks, are crucial elements in urban development due to their social and ecological benefits. Hence, the role of the public is crucial and has equal importance with other stakeholders such as the local authorities and development consultants in terms of working towards achieving a public responsive design scheme for the development of public parks in Malaysia. The architectural and design elements of public parks carry social and cultural values for an individual, thus leading to social inclusivity and a sense of belonging to the public parks [25,62].

The discussion of public parks and the issues pertaining to Malaysian public parks demonstrate the significance of the implementation of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia. An integrated design framework that incorporates PPE in the design of public parks promotes the sustainable development of the long-term growth of public parks in Malaysia. As a result, the PPE in designing public parks has the potential to address the issue of underutilisation of public parks by obtaining direct feedback from the public through the PPE. The PPDCM indicators discovered in this research are tabulated in Lazarsfeld’s scheme for further analysis.

6. Methodology

In this study, the Lazarsfeld’s scheme methodology was adapted for tabulating the identified variables into endogenous variables and exogenous variables. Even though Lazarsfeld’s theory is commonly used in mass media communication studies [7], this research adapts a similar method to that of Lazarsfeld’s, known for its technique of approaching public respondents about the attentive objective of this research. Lazarsfeld’s scheme is mainly used for social science questionnaire-based studies [7]. Therefore, this research is oriented towards a public opinion.

Based on the scheme, the construct operational definition was developed by identifying the dependent variables (attribute of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia) and independent variables (development stage, method of approach, type of public, and public parks design criteria) and relevant indicators in every variable of the study. The constructs (public participation and public parks) are the main keywords of the study. Additionally, a variable measurement table was developed for the measurement of indicators. The sequence of Lazarsfeld’s scheme is shown in the results section. Operationalisation refers to the conversion of abstract concepts into measurable observations, in which there is a systematic data collection on processes and phenomena that are not directly observed. Operationalisation is important to remove ambiguity in concepts by specifying the operations that will be measured. Therefore, operationalisation translates the meaning of the constructs provided by the theoretical definition into a prescription for measurement. Operational definitions or prescriptions for measurements are statements that describe measurements and statistical operations. The three main components in operationalisation including: (1) social class, (2) morbidity, and (3) self-efficacy belief.

7. Results and Discussion

Table 2 shows the operational definition including two constructs identified as follows: (1) public participation and (2) public parks. Public participation is defined as an active public involvement in decision-making activities in policymaking, and physical development towards meeting the needs of the people. A public park is an open space that is associated with public and recreational activity among the public.

Table 2.

Operational definition of the construct.

Table 3 shows the variables and measurements for each construct. There were five variables identified, including (1) attribute of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia, (2) development stage, (3) method of approach, (4) type of public, and (5) public parks design criteria. The attribute of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia is to measure public awareness of public participation activities in general.

Table 3.

Variables and measurement of PPE.

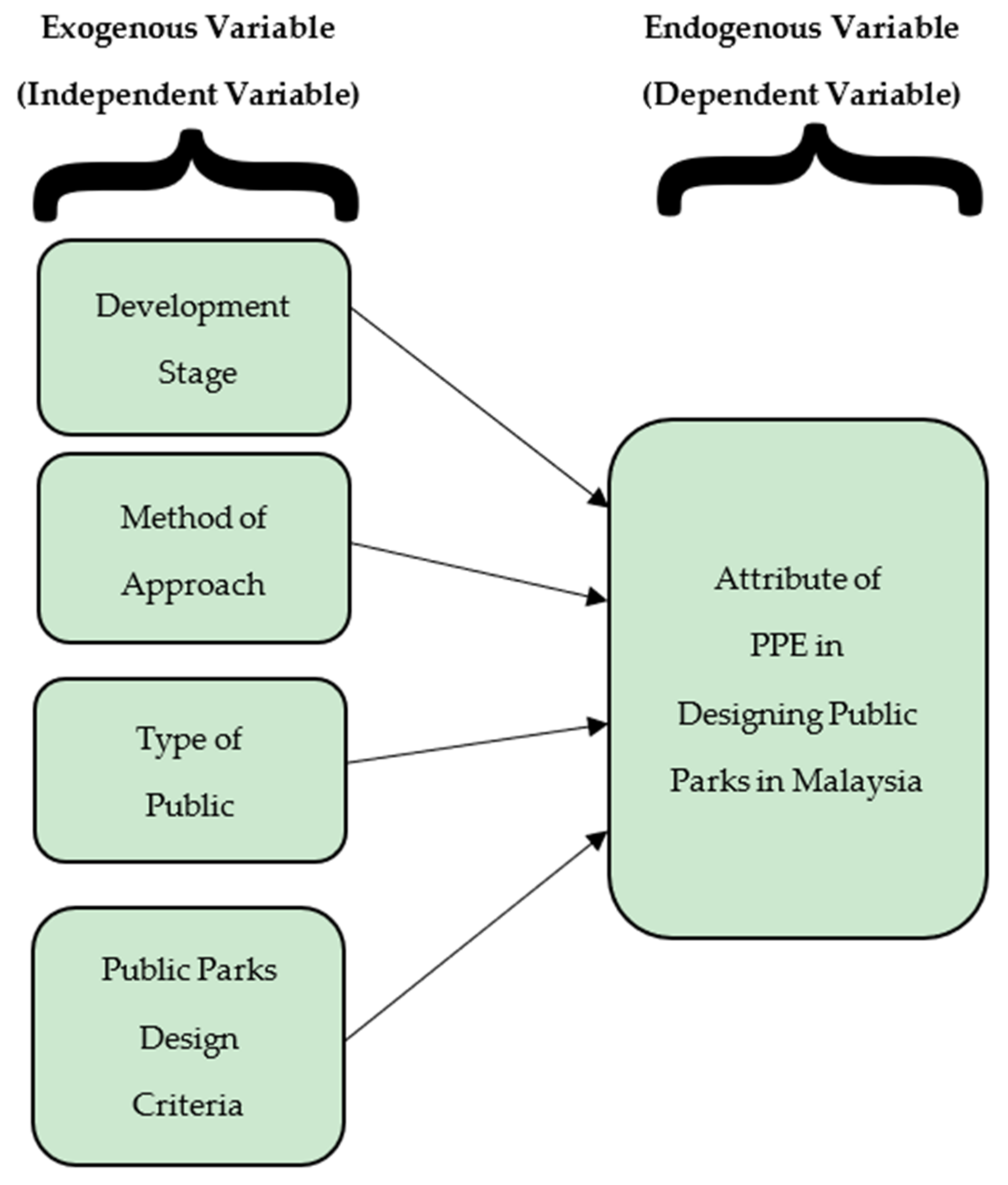

Figure 3 shows the conceptual framework of this research, which is derived from the table of variables and measurement of PPE. There are two types of variables that have been classified under the conceptual framework which includes endogenous variable and exogenous variables. The endogenous variable (dependent variable) involves the attributes of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia while the exogenous variables (independent variables) include the development stage, method of approach, type of public, and public parks design criteria. The conceptual framework demonstrates the relationship between the endogenous variable and the exogenous variable.

Figure 3.

A conceptual framework of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia.

8. Conclusions

PPE in general is not a common practise in local civil policy in Malaysia, despite the mandate given to the LA21 to support the SDGs and the notion of democratic governance. This research determines one dependent variable and four independent variables. The endogenous variable is the attribute of PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia, while the four exogenous variables are the development stage, method of approach, type of public, and public parks design criteria. The contribution of this paper includes public participation in civil policy in designing public parks as it demonstrates the public’s responsive notion towards sustainable development in Malaysia. Consequently, the table of operational definition of the construct, the table of variables and measurement of PPE, and the conceptual framework of the variables for PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia represent the outcome of the research.

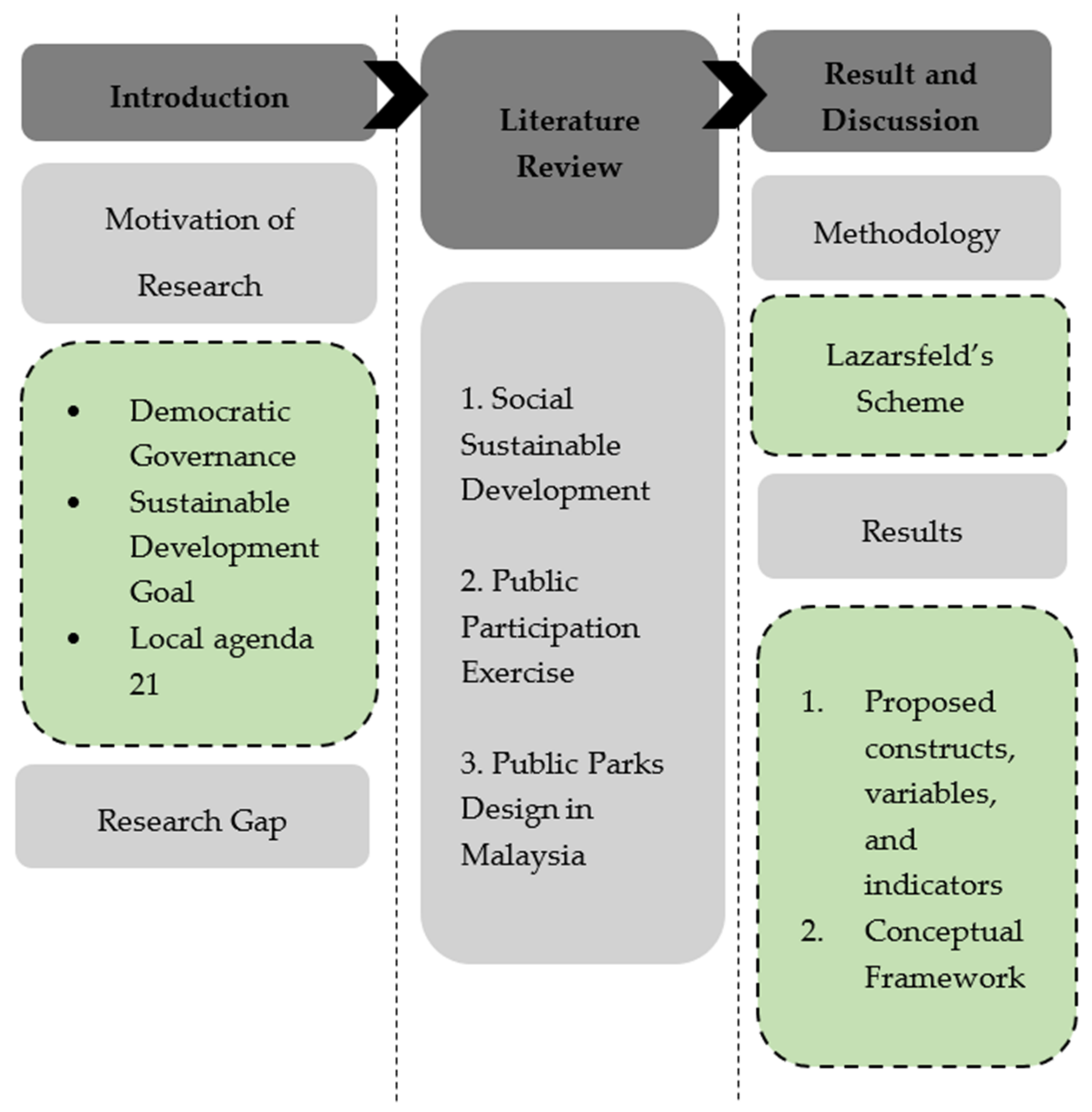

The process of obtaining the variables and indicators for PPE in designing public parks in Malaysia is shown in Figure 4. This research is limited to the context of Malaysia as the design framework is place-dependent. A further investigation into the PPE framework in designing public parks in Malaysia will be conducted to measure the relationship between endogenous and exogenous variables. Furthermore, it is highly recommended to further investigate the PPE design framework for other public facilities, such as sports facilities and health facilities.

Figure 4.

Structure of paper.

Author Contributions

U.N.S. carried out the study and the main drafter for the article; M.K., M.D.P. and T.J.D. involved in supervising the work and contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Reading-Malaysia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kamaruddin, N.; Rogers, R.A. Malaysia’s democratic and political transformation. Asian Aff. Am. Rev. 2020, 47, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moten, A.R. The 14th general elections in Malaysia: Ethnicity, party polarization, and the end of the dominant party system. Asian Surv. 2019, 59, 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, H.A.; Mohamed, A.M.; Lawton, A. Assessing Public Participation Initiatives in Local Government Decision-Making in Malaysia. Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 39, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, S.; Hassanzadeh, M.; Forghanifar, B. Role of Public Participation in Sustainable City. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Research in Science and Technology, Kuala Lumpur, Malasya, 15 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eckerd, A.; Heidelberg, R.L. Administering Public Participation. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2019, 50, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wu, Q.; Wu, W.; Liao, W. Decision-Maker-Oriented VS. Collaboration: China’s Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Cai, Q.; Huang, Y.; Lang, W. System Building and Multistakeholder Involvement in Public Participatory Community Planning through Both Collaborative- and Micro-Regeneration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santé, I.; Fernández-Ríos, A.; Tubío, J.M.; García-Fernández, F.; Farkova, E.; Miranda, D. The Landscape Inventory of Galicia (NW Spain): GIS-web and public participation for landscape planning. Landsc. Res. 2018, 44, 212–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pløger, J. Politics, planning, and ruling: The art of taming public participation. Int. Plan. Stud. 2021, 26, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, D.; Schweizer, P. Public values and goals for public participation. Environ. Policy Gov. 2021, 31, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 10, pp. 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Kadir, S.A.; Jamaludin, M. Universal Design as a Significant Component for Sustainable Life and Social Development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 85, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals Relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-DESA. Sustainable Development Goals. 2021. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Abidin, N.I.; Zakaria, R.; Aminuddin, E.; Saar, C.C.; Munikanan, V.; Zin, I.S.; Bandi, M. Malaysia’s Local Agenda 21: Implementation and approach in Kuala Lumpur, Selangor and Johor Bahru. IIOAB J. 2016, 7, 554–562. [Google Scholar]

- Nurudin, S.M.; Hashim, R.; Rahman, S.; Zulkifli, N.; Mohamed, A.S.P.; Hamik, S.A. Public Participation Process at Local Government Administration: A Case Study of the Seremban Municipal Council, Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hassan, A.M.; Lee, H. The paradox of the sustainable city: Definitions and examples. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 17, 1267–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngah, K.; Mustaffa, J.; Zakaria, Z.; Noordin, N.; Sawal, M.Z.H.M. Formulation of Agenda 21 Process Indicators for Malaysia. J. Manag. Sustain. 2011, 1, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ujang, N.; Moulay, A.; Zakariya, K. Sense of Well-Being Indicators: Attachment to public parks in Putrajaya, Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulay, A.; Ujang, N. Insight into the issue of underutilised parks: What triggers the process of place attachment? Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2021, 13, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.; Clayden, A.; Cameron, R. Tropical urban parks in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Challenging the attitudes of park management teams towards a more environmentally sustainable approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgul, E.; Luo, L.; Wei, S.; Pei, C.D. Sense of Place or Sense of Belonging? Developing Guidelines for Human-centered Outdoor Spaces in China that Citizens Can be Proud of. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridings, J.; Chitrakar, R.M. Urban design frameworks, user activities and public tendencies in Brisbane’s urban squares. Urban Des. Int. 2021, 26, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2020. Available online: https://report.hdr.undp.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Too, L.; Bajracharya, B. Sustainable campus: Engaging the community in sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karji, A.; Woldesenbet, A.; Khanzadi, M.; Tafazzoli, M. Assessment of Social Sustainability Indicators in Mass Housing Construction: A Case Study of Mehr Housing Project. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R.; Conroy, M.M. Are we planning for sustainable development? An evaluation of 30 comprehensive plans. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A. Sustainable Communities and Sustainable Development: A Review of the Sustainable Communities Plan; Sustainable Development Commission: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen, S.E.; Sarkissian, S. City size and fund performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 92, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magis, K. Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNPAG. UN Public Administration Glossary. 2013. Available online: http://www.unpog.org/page/sub5_3.asp (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Ahmadi, D.; Bandung, I.U.I.; Rachmiatie, A.; Nursyawal. Public Participation Model for Public Information Disclosure. J. Komun. Malays. J. Commun. 2019, 35, 305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Jibladze, G.; Romelashvili, E.; Chkheidze, A.; Modebadze, E.; Mukeria, M. Assessing Public Participation in Policymaking Process; WeResearch: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2021; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jekabsone, I.; Sloka, B. The role of municipality in promotion of well-being: Development of public services. In Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2017; pp. 713–721. [Google Scholar]

- Wampler, B.; Touchton, M. Designing institutions to improve well-being: Participation, deliberation and institutionalisation. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2019, 58, 915–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, P.A. Social participation, health literacy, and health and well-being: A cross-sectional study in Ghana. SSM-Popul. Health 2018, 4, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, S.; Mackrill, J.; Cain, R.; Strelitz, J.; Gate, L. Developing interior design briefs for health-care and well-being centres through public participation. Arch. Eng. Des. Manag. 2015, 11, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, N.A.A.; Pazmiño, M.G. Principios de sostenibilidad social en el diseño urbano. Rev. Científica Retos Cienc. 2018, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yuliani, S.; Hardiman, G.; Setyowati, E. Green-Roof: The Role of Community in the Substitution of Green-Space toward Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, A.; Wille, R. Designing Droplet Microfluidic Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.A.M.; Arifin, K. Penglibatan Awam Sebagai Pembuat Keputusan Dalam Rancangan Tempatan Pihak Berkuasa Tempatan (Public Participation as a Decision Maker in Local Plans at Local Authority). Akademika 2020, 90, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Siew, R.Y.J. Green Township Index: Malaysia’s sustainable township rating tool. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Engineering Sustainability; Thomas Telford Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Shan, P.; Wang, C.; Quan, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhao, C.; Wu, G.; Deng, H. Assessment of urban sustainability efficiency based on general data envelopment analysis: A case study of two cities in western and eastern China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Qiang, G.; Zuo, J.; Zhao, X.; Chang, R. What are the Key Indicators of Mega Sustainable Construction Projects?—A Stakeholder-Network Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larco, N. Sustainable urban design—A (draft) framework. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEED-ND. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Neighbourhood Development 2021. Available online: http://leed.usgbc.org/nd.html (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- BREEAM. Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method. 2021. Available online: https://www.bregroup.com/greenguide/calculator/page.jsp?id=2071 (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- IDP. The Integrated Design Process. 2021. Available online: http://iisbe.org/down/gbc2005/Other_presentations/IDP_overview.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- SITES-V2. The Sustainable Sites Initiative. 2021. Available online: http://www.sustainablesites.org/get-started-sites-v2-rating-system (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- GreenMark. Green Mark for Non-Residential Building NRB: 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.bca.gov.sg/greenmark/others/Green_Mark_NRB_2015_Criteria_Draft_R3.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- GBI. GBI Assessment Criteria for Township. 2017. Available online: https://www.greenbuildingindex.org/Files/Resources/GBI%20Tools/GBI%20Township%20Tool%20V2.0.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Adiati, M.; Lestari, N.; Wiastuti, R. Public parks as urban tourism in Jakarta. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.H. Project Review: Public Park Planning and Design as Contribution from Multidiscipline Fields in Built Environment. J. Alam Bina 2006, 8, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sakip, S.R.M.; Akhir, N.M.; Omar, S.S. Determinant Factors of Successful Public Parks in Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakip, S.R.M.; Akhir, N.M.; Omar, S.S. The Influential Factors of Successful Public Parks in Malaysia. Asian J. Behav. Stud. 2018, 3, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Mohan, G.; Curtis, J. Public park attributes, park visits, and associated health status. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 199, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngesan, M.R.; Karim, H.A.; Zubir, S.S.; Ahmad, P. Urban Community Perception on Nighttime Leisure Activities in Improving Public Park Design. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ma, W. Sustainable Urban Community Development: A Case Study from the Perspective of Self-Governance and Public Participation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C. City of culture, city of transformation: Bringing together the urban past and urban present in The Hull Blitz Trail. Urban Hist. 2020, 48, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Schebella, M.; Weber, D. Using participatory GIS to measure physical activity and urban park benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 121, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JPBD. Perancang Bandar Dan Desa. 2016. Available online: https://www.townplan.gov.my/index.php?option=com_docman&view=flat&layout=table&category%5B0%5D=48&category_children=1&own=0&Itemid=427&lang=ms&limit=20&limitstart=20 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- UNSDG. Sustainable Development. 2019. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnerships/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Bakar, J.A. A Design Guide of Public Parks in Malaysia; Penerbit UTM: Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.H. The Architecture of Public Park: Fading the Line between Architecture and Landscape. J. Alam Bina 2006, 8, 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Khaza, M.K.B.; Rahman, M.; Harun, F.; Roy, T.K. Accessibility and Service Quality of Public Parks in Khulna City. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).