Abstract

This paper reviews oral histories and established scientific materials regarding wild reindeer (Rangifer tarandus spp.) in the Southern Sakha-Yakutia, in the Neriungri district and surrounding highlands, river valleys and taiga forest ecosystems. Wild reindeer is seen as an ecological and cultural keystone species through which environmental and social changes can be understood and interpreted. Oral histories of Evenki regarding wild reindeer have been documented in the community of Iyengra between 2005 and 2020. During this 15-year-co-researchership the Southern Sakha-Yakutian area has undergone rapid industrial development affecting the forest and aquatic ecosystems. The wild reindeer lost habitats and dwindles in numbers. We demonstrate that the loss of the wild reindeer is not only a loss of biodiversity, but also of cultural and linguistic diversity as well as food security. Our interpretative and analytical frame is that of emplacement. Socio-ecological systems have the potential and capacity to reconnect and re-establish themselves in post-extractive landscapes, if three main conditions are met. These conditions for successful emplacement include (1) surviving natural core areas, (2) links to cultural landscape knowledge and (3) an agency to renew endemic links.

1. Introduction

Evenki live over a vast geographical range in East Siberia, Far East of Russia, Northern China and Mongolia [1,2,3]. Wure’ertu [4] provides us with an Evenki-authored view of the distant past and the deep memories the Evenki have over large spatial scales, essentially spanning the continent. Yet, each region and community has a unique heritage of the Evenki culture [1,2,5].

It is estimated that the entire Evenki community has approximately 36,000 members today, and ca. 7000 speak the language. Traditional livelihoods have revolved around nomadic reindeer herding, hunting and fishing [6]. There is also an Evenki community in China. This research focuses on the Evenki community of Iyengra and the surrounding taiga camps, in the Southern Sakha-Yakutia (spelling also for example Iakutia).

Collaborations and co-researcher -ship have emerged in the past 10 years in different parts of the Evenkia (here referring to the larger Evenki home realm, see more of this concept for example in [7] and other parts in [8]), where reindeer herders and women from the taiga camps have been positioned as equal partners in research. This structure has been in place in our long-term research from the very beginning. The emergence of the Evenki landscape studies [9,10,11] have offered similar approaches in research. More precisely, the people in the community shared their oral histories over the past years to form an oral history corpus. Individual contributors own their knowledge and are acknowledged by name unless they have requested anonymity. Two of the authors of this article are Indigenous (Evenki and Yukaghir) and have led the research effort in the community and in the republic for 15 years.

Our case community, the Evenki of Iyengra, has faced a continuous, though varying over time, pressure of displacement since the days of the first encounters with Russians in the early 17th century, including forced settlements in the 1920s. We summarize these community changes briefly below and throughout the article but our primary focus is on wild reindeer as a keystone indicator of change.

One of the first encounters with Russians took place in 1619 when Petr Albychev and Cherkas Rukin enslaved Evenki nobility Iltik. Since this event 400 years ago, the Evenki have interacted with the Indo-European peoples. Prior to contact with Russians the Evenki had met with the Sakha (Yakut) people, with whom the relationship had ranged from trade to war. During those days, the Evenki were also aware of and had connections to a range of Siberian nations, such as the Chukchi, Even and Yukaghirs [12]. For example the place names surrounding Iyengra reflect in part the meshed landscape and influence of the Sakha on the Evenki homeland [6].

Neriungri, the regional district where Iyengra is located, is a southern region of the Republic Sakha-Yakutia in the Russian Federation, located close to the Chinese border. The population of the district is about 75,000, most of it being urban. Neriungri, the capital city, is also the centre for coal-mining operations. The district produces up to 75% of the 10 million tons of coal that is produced in Sakha annually [12,13,14].

Southern Sakha-Yakutia is part of the continental climatic zone. Siberian larch, other coniferous trees and birch cover much of the taiga. The village of Iyengra is located in the southern part of the Sakha. Mountains and large hills dominate the landscape, combined with shallow rivers flowing in the valleys. For example, the Aldan catchment area, a subcatchment of Lena River, flows through the district. Winters are usually very cold with small amounts of snowfall. Temperatures can plummet down to −50 °C and below.

Springtime is often short with snowmelt already well under way in April. Summers are continental and hot. Autumn brings the first frosts, often in September or October. In addition to terrestrial hunting and herding economies, fishing for salmonid fish such as trout, grayling and whitefish is important. This is reflected in many Evenki place names around Iyengra [6,15]. They play an important role in the traditional food security of the community. Evenki have used these salmonid fish as cultural bioindicators to assess the degradation of river health and change over time [6,16]. They also place significant cultural value especially to local trout as a culturally relevant species.

Under the Soviet regime and during the post-Soviet years, the Evenki lands and waters became a target of expansive industrial operations [14,17,18]. Mining for coal and gold, hydropower construction, energy pipelines [19] and many other infrastructure projects mark the landscape [14]. This expansion widely and thoroughly altered the post-Ice Age landscapes of the southern Sakha-Yakutia. During Soviet times, most of the Evenki in the area were officially relocated into the village of Iyengra, which was founded on the catchment area of the river of the same name in 1926, along the traditional nomadic routes of the Evenki [6].

According to the 2018 census (which is the most recent in public records), the population of Iyengra is 918, of which the majority (over 800) is Evenki. Some of the Iyengra Evenki spend most of the year on the taiga but are registered in the village (Other hunter-herders, like Kolesov, shared their oral histories with willingness and consent to be named. If this has been the case, we have quoted a person direct with names.). Other nationalities in the village include for example Even, Karelian, Russian and Sakha-Yakut peoples. Evenki children go to school in Iyengra, which functions as a residential school where the children of the reindeer herders spend the winter season while their parents are working in the taiga.

We, the authors of this paper, have been working in the community to document and co-research Evenki knowledge between 2005–2020. The original invitation to work with the Evenki of Iyengra originated amongst Evenki scholars and leaders in Yakutsk. The original group was led by Evenki Galina Varlamova, Evenki Tamara Andreeva, Evenki Anna Myreeva and Yukaghir Vyacheslav Shadrin. The aim was to seek new collaborations to strengthen Indigenous knowledge preservation, document climate and ecological observations in the village and surrounding taiga forest ecosystems and to position the rapid development plans for the region into a broader context of the Evenki culture, way of life, food security and traditional professions.

In the present paper, we focus on available science and Indigenous Evenki knowledge of the wild forest reindeer (Rangifer tarandus Linneaus, 1758, Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] name the southern reindeer to be Rangifer tarandus valentinae Flerov, 1933 and speculate further that the southern herds would be actually close to the Ohota subspecies R. tarandus phylarchus Hollister, 1912 [21] in Southern Sakha-Yakutia).

Reindeers are overall central to the Evenki in terms of food security, cultural and linguistic knowledge, beliefs and to the maintaining of social order, justice and knowledge of nature across the Evenki living space [5,22,23,24]. Vorob’ev [24] (p. 34) quotes G.M. Vasilevich, a specialist in Evenki language and culture, sharing “that the Evenki considered that moose and (wild rein)deer were sent by a spirit—the master of the taiga: The ancient belief in their resurrection survived for a long time. After processing the meat and hides, hunters were supposed to collect all the bones of the skeleton and to rest them on a platform [gulik], so that dogs could not drag them away”.

According to Vorob’ev [24] in Krasnoyarskii krai the northern wild reindeer is known as as severnyi dikii olen. The word dikovka is derived from dikii, Russian for “wild.” Vorob’ev [24] (p. 36) continues that the “seasonal hunt for migrating northern wild deer called dikovka, as in most regions of Siberia, underscoring the distinction between the northern wild deer and its domesticated cousin. The wild deer hunters are called dikovshchiki.” Shubin [24] (p. 34) reports that in Buryatia the meat and appreciation of wild reindeer meat as food comes behind for example moose, even though overall wild reindeer are important to the culture.

Overall there are at least 71 distinct endemic concepts for the reindeer, domestic and wild (same biological animal, different stocks and uses for the Evenki) [25]. When accounting for dialects and synonyms, this equates to hundreds of specific reindeer-related concepts. The language differentiates the animals according to age characteristics, fur color, as well as their character and behavior. To offer some examples:

- “sonnga” = newborn calf

- “ukoto” = nursing calf

- “epchakan” = female reindeer, one to two years old

- “ektana” = bull reindeer, two to three years old

- “semeki” = female reindeer that does not let people approach it during calving

- “arkichan” = old riding (on saddle) reindeer

- “kongnomo”, “kongnorin” = black color and fur color of reindeer

- “igdiama”, “igdyama” = ginger fur color

- “kurbuki” = reindeer that has become wild

- “sungnaki” = restless reindeer(summarized from [26])

Specifically for wild reindeer, people in the oral history materials pointed for example to kuraika, which can be translated as ‘autumn male wild reindeer’. Accordingly neӈcheng is the ‘spring wild reindeer’ (see discussion in [10] on tensions between ‘official transliterations’ and vernacular spelling of Evenki).

Given the vast industrial developments, infrastructure process and mining in the Southern Sakha-Yakutia space, the wild reindeer are disappearing and losing their ancestral ranges [20]. We explore the key implications, observations and ultimately, solutions, to these negative drivers.

Several earlier summary reports and publications have been released from this on-going knowledge documentation and Indigenous knowledge work (see for example [6,27,28,29]).

The Evenki have been studied at length over the past years, with a primary focus on their belonging to the taiga forest ecosystem [7,9,10,15,22,24,30,31,32]. Already during the historic, and later Soviet times, the Evenki were a target of anthropological and geographical interest, with ‘classical’ desciptions of their lives, human societies and ways of life documented. During the Russian and Soviet era, the Evenki were targets of scrutiny and ethnographic investigations that have provided an outsider view of the transitions and changes of the Evenki societies across their vast home area.

Authors such as Arkadii Anisimov, Sergei Shirokoroff, Anna Sirina and perhaps most importantly, Glafira Vasilevich [e.g., see English summaries in [9,24], researched the Evenki customs and lifeways from the late 1800s to the mid- and late-1900s. Evenki Alexander Sergeevich Shubin (born in 1929, see collections of works in [23]) from the Khabarzhan area of the Barguzinsky region produced a large collection of Buryat Evenki histories and change during the Soviet era. He has written (during Soviet times and being affected by them, see [5,22,23] from an ‘(Soviet) internal viewpoint on the Evenki historic development and cultural issues, in some ways, much like Varlamova [1].

Emerging from the 1990s, the concept of Indigenous communities of Northern Russia being in a position of co-interpreting and researching with outside scholars started to gain a foothold (for notions of inherent, endemic knowledge of a situated heritage, see [27], and for the persistence of the ‘Evenki as other’ see [33]). For example Safonova and Sántha [34] have reviewed the ‘classical’ intepretation of ‘hunter gatherer Evenki’ and advanced a more broad interpretation. We follow such overall positioning in our present work and have also included the voices of the Evenki academic scholars, such as the late Galina Varlamova [1], Wure’ertu [4] and Anna Myreeva [25], as well as our Evenki co-researcher Tamara Andreeva in Yakutsk. Overall, we use this co-interpretation (see below) and ‘novel research space’ in our approach of emplacement of the Evenki, described in more detail below.

The empirical section of the article begins with a description of the traditional concepts, cosmological narratives and aspects of the Evenki and thereafter focuses on the wild reindeer and change in the community over our review period.

2. Materials and Methods

We frame our article on two theoretical understandings. Following Montonen [35] and in part from Vorob’ev [24], we build our case around the understanding that the wild forest reindeer (Rangifer) for the Evenki is a cultural keystone species [26]. Montonen [35] demonstrated in the case of the Sámi and Finnish wilderness communities that the wild forest reindeer maintained the land uses, oral histories, traditional songs, hunting patterns and food security of several forest communities until it was over harvested and the stocks collapsed in NE and Eastern Finland, early 1900s and in 1928, respectively.

This sped up, according to Montonen [35], the erosion of traditional knowledge. The practise and the time-consuming actions of hunting wild reindeer in the forest fell out of use, either then replaced by other activities or species, such as increased hunting pressure on moose, or a switch to larger scale reindeer herding. More recent scholarship, such as Frainier et al. [26] agrees, and emphasizes the triangulation between Indigenous knowledge, linguistic and biological diversity on which the people depend.

Second, as we explore the potential for maintaining and fostering the return of wild forest reindeer into the Southern Sakha-Yakutia we draw on Mustonen and Lehtinen [36]. They argue that whilst modernity and associated natural resources extraction has altered, often permanently, natural systems, they contain elements of a renewed emplacement despite the damages.

They [36] investigated how community emplacement functions. Here we can summarize that it is an emerging spatial understanding of severed, preserved and reconnected belongings to a place. We wish to offer a renewed emplacement approach as a mechanism to understand the complex reality (and potential future pathways) of the present-day Evenki life in Iyengra. More precisely, investigations of emplacement require the following components:

- some remaining natural ecosystems having enough carrying capacity and production that nature-based traditional livelihoods have maintained “core” areas, despite extractive / altered impacts from human uses

- a traditional knowledge corpus of a cultural engagement with a landscape of former but recent (often discontinued or abandoned) practices that is still within community’s reach

- a concentrated willingness and actionable process to maintain, and where emplacement allows, revitalize nature-based livelihoods, cultural practices and specific engagements with the surround ecosystems(summarized from [36], with elements of scaling the loss from [24]).

We need to be clear also that if industrial and extractive land uses have created conditions where emplacement does not meet these three criteria, evident and permanent loss may happen. Emplacement is not an automatic solution space or to be taken for granted. It is a concentrated, combined effort of emerging and surviving potential of socio-ecological systems combined with a determined agency [37] that is willing to implement and position emplacement as a realistic potential future pathway.

We recognize the important descriptive and interpretative early works building on Russian and Soviet ethnography (Arkadii Anisimov, Sergei Shirokoroff, Anna Sirina, Glafira Vasilevich and others). We also acknowledge the present ethnographical works that have partnered with the Evenki to understand change, continuity and loss [7,9,10,15,24,30,31] and identities [32] and provide valuable descriptions and precise documentation of the Post-Soviet years.

Our emplacement conversation builds to conceptualize a ‘third way’ in the science-Indigenous nexus, where the Indigenous peoples self-articulate and co-produce the situational analysis and potential solution spaces. In order to realize Indigenous rights and authorship, we also have to critically self-reflect on the established academic practices and the othering that has been one of the underlying drivers of Russian and Siberian ethnography [38].

In our understanding emplacement offers a situated, post-colonial and localized assessment of a post-industrial situation [36] where the empirical situation ‘as-it-unveils’ provides the best window to the issues. This has also implications to the future of the Arctic and Indigenous studies and how we understand change, belonging, memory and landscape studies.

In the context of Iyengra, we frame this work to build on the fact that the Indigenous forest lifestyles and presence have continued across and in the middle of the industrial developments [14]. For example, continued fish harvests and reindeer herding demonstrate a range of qualities and adaptations to the ecological alterations that do produce cultural continuums even if in the middle of industrial upheaval [14].

We can see these examples constitute endemic (self-defined, self-articulated) acts of emplacement [27,36]. This rests on tensions between preserved traditional lifeways of the taiga and the impacts of industrialization. They constitute also acts of co-intepretation. This emerges in oral histories and choices of narration Evenki themselves priorize—overall in our study period with the community members the fate of wild reindeer as a overall theme and the specific drivers was raised and resulted in the analytical frame of this article.

Co-interpretation comes in many forms, one of the most central being agency [37]. It allows outside researchers to refine their view and on the other hand addresses the power relations in scholarship where the local/community/knowledge holders have an even space for their priorities as opposed to outside, prior and set expectations in research. Huntington et al. [37] value the inherent value of community choice, knowledge and interpretation as unique—providing a tension line between general and specific. In this research we address this tension by allowing the co-intepretation to flow from the oral history corpus which is then further reflected on by T.A., Evenki co-author to maximize the voices and knowledge of the Evenki as they see it. All interpretation is always an interpretation. However, as Huntington et al. [37] show, co-intepretation advances the scholarly process in marked ways and it is applied here with rigor.

Traditional skills do not necessarily disappear during industrial modernization. Instead, in certain encouraging conditions, they can re-emerge and pave routes to endemic futures. In the conclusions we discuss these aspects of potentials of preservation of wild reindeer stocks (and connection to Evenki) in Southern Sakha-Yakutia.

As a culturally-positioned solution we refer to such an (future) act of emplacement as nimat. Nimat refers to a process, ceremony and distribution system by which successful hunters share their wild reindeer catches amongst the Evenki community [1]. The purpose of this distribution of assets is linked with community cohesion and food security—those who cannot hunt, i.e., the women, Elderly, children, are also given food by the providers. In nimat, wild reindeer provides for the Evenki.

We can see the forest ecosystem services culminating in nimat for the Evenki—what is taken, is shared, and overharvesting is strictly observed and forbidden. McNeil [2] highlights the role of the revival-focused concepts amongst the Evenki. We therefore use the concept of nimat as a concept in this vein. We following co-interpretation priorities from the community envision rewilded Iyengra territories to be a nimat of the future—an act of emplacement, a return and a comeback to the restored taiga and restored beings in the forest. Whilst this may seem unrealistic at present, the situation has changed in the recent past in a speedy manner [38].

For capturing the Indigenous knowledge of the Evenki regarding the southern stocks of the wild reindeer, we have reviewed over 80 primary oral history files that have been translated from Evenki or Russian (depending on the case) into English, as well as diary entries, written statements communicated by email (especially for 2019–2020 season) from Iyengra on the situation of the wild reindeer over the decades. Our primary focus is on the 15 years between 2005 and 2020, but we add Indigenous knowledge of past changes on wild reindeer where applicable, also reviewing the literature (for example on losses of knowledge at [24]).

In 2007, a large international conference “Traditions of the North” was organised in Iyengra to discuss the midpoint results, natural resources extraction of the region and further cooperation points. This allowed the community members participating to hear of the results and discoveries until 2007. Between 2012 and 2019, the materials of the oral histories were summarised into an online Atlas (see [6]) that has been made available, based on the wishes of our co-researchers, in Russian in January 2020 (an Evenki version may be a future option).

The primary oral history tapes were recorded by the authors (Tero Mustonen, Kaisu Mustonen, Tamara Andreeva), mostly in the reindeer camps around Iyengra, or in the community itself. Consent forms were used. Anonymity was offered and respected when requested. Some summaries and examples of the oral histories have been shared in Mustonen [27], Lehtinen and Mustonen [28], Mustonen and Lehtinen [29] and in Evenki Atlas [6].

The primary tapes are located in oral history archives in Yakutsk and in Finland. Vyacheslav Shadrin led this process. Each tape was transcribed and analyzed for contents and thematized. Evenki translations of interviews were carried out by Indigenous co-authors Yukaghir Vyacheslav Shadrin and Tamara Andreeva, an Evenki herself. Interview tapes exist in WMA and MP3 format in the archives.

Given the thematic focus on wild reindeer we concentrate on offering the trends and key messages from the oral history documentation and other sources, with carefully chosen oral history quotes where applicable for the results. These quotes were a question of co-intepretation of needs—the losses of wild reindeer, observations and ultimately impacts of the losses emerge strongly from the oral history corpus.

For a broader temporal-analytical frame, building on Montonen [35] and Mustonen and Lehtinen [36] we use three conceptual-temporal themes

- baseline science on wild reindeer in general in Sakha-Yakutia

- the situation from pre-industrial era into first industrial changes until 1990 (displacement)

- shifts from 1990s to the second wave of industrial land use 2020s (emplacement potential emerges)

These will service as a mechanism to discover the status, trends and intertwined impacts of the wild reindeer numbers, populations and their observed or assumed disappearance. Then the fourth and the largest analytical section “Evenki knowledge of the reindeer” highlights these implications for the Evenki (see the loss of knowledge in another Siberian region in [24]).

3. Results

3.1. Understanding the Baseline of Wild Reindeer in Southern Sakha-Yakutia

An independent survey conducted by Argunov [39] explains that the wild reindeer stocks in Sakha-Yakutia can be divided roughly into tundra wild reindeer (populations of Leno-Olenok, Indigirka and Sundrun populations) and then taiga, or forest, reindeer stocks that are often understood to consist of Western taiga, Southern Sakha and mountainous taiga populations. An earlier, separate study was conducted by Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20]. We use these as a baseline and indicators of change in summary form from scientific sources.

In this paper we focus, according to the categorisation of Argunov [39], on the Southern Sakha wild reindeers and more specifically on those herds which have occupied and continue in part to occupy the Neriungri region. We should note that despite some of the monitoring efforts presented in this paper, the exact populations on 20 km × 20 km scales remain still a gap, and there is a need for further research and documentation.

3.2. From Pre-Industrial Populations into the First Wave of Industrial Land Uses 1975–1990

Argunov [39] presents a fairly recent historical assessment of the herds of the wild reindeer in the region. His results build on aerial and on-the-ground -surveys of stocks as well as hunter inventory data from the ministerial sources in Yakutsk. The large stocks of 1960s referred to by Argunov in Krivoshapkin and Mordosov’s [20] opinion are based on the re-organisation and liquidation of many wilderness and rural communities in the 1960s (so-called Liquidation of Villages with no Prospects). This provided more spatial extent and habitat to the wild reindeer.

Aerial surveys of wild reindeer in the taiga parts of Sakha-Yakutia can be summarized in the following:

- 1960: 100,000 animals

- 1975: 57,000 animals

- 2001: 24,500 animals

- 2010: 24,500 animals(based on [39], partly complemented by [20])

Rather positively Argunov [39] presents also data from the ground monitoring which has been re-started in 2010s and summarized below:

- 2013: 70,000 animals

- 2014: 70,000 animals

- 2015: 85,000 animals

- 2016: 63,500 animals

- Late 2010s: 85,000 animals(based on [39])

Argunov [39] says that the southern taiga herds of the wild reindeer would number around 7900 animals. He points out the rather massive (75%) collapse in the aerial survey numbers of the southern wild reindeer over the span of 50 years, despite the aerial and spatial extent being rather secure.

He also points out that the southern herds have moved in the more recent 2000s into the middle parts of the Republic and have merged with herds there—a potential consequence of the industrial development in the south. Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] mark the southern herds to number around 8000 in 2001 and they list the overall forest reindeer numbers to be around 12,000 animals in 2001 (significantly lower than presented by Argunov for the same period).

This period in the lives of the Evenki was a massive transformation, and an often forced process. The self-governance of the life in the taiga changed into a mixed, and more controlled Soviet era, when the settlement of Iyengra was founded in 1926. Natural ecosystems remain relatively intact until 1970s—we can also see the preservation of cultural knowledge of wild reindeer to have survived better, given that we can assume the herds were bigger, closer and healthier.

From 1970s onwards the advancement of several industrial actions, including the Baikal-Amur railroad and proliferation of coal mining started to affect the Evenki nature-based life. Many Evenki had been working with mineral exploration crews as guides. The building of the city of Neriungri in 1975 sped up the infrastructure and road construction in the region.

In 1991 the Evenki faced the dissolution of the state farm -based reindeer herding. Lack of financial assets triggered what Pika [40] has called “neotraditionalism”, or the reawakening of modes of life building on traditional taiga life. We can see this as a first era of a renewed emplacement [36] —wild reindeer stocks also benefitted from reduced industrial activities. Some Evenki established obshchinas, Indigenous kin-based community-cooperatives as a basis of private reindeer herding. For example Gonam is one of these communities [6]. The conceptualisation of nomadic schooling also emerged from within the freedoms of the 1990s [30].

3.3. 1990s into the Second Wave of Industrial Land Uses 2005–2020

As a whole Argunov [39] determines that the populations of the taiga wild reindeer are rather stable on a republic-wide level. Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] disagree to certain extent in those data sets where their observations overlap (until 2007). They are concerned about the loss of numbers of animals evident in the aerial survey data and have an estimation of 24,500 wild reindeer in all of Sakha-Yakutia. They name the main drivers of losses as:

- wildfires and the long recovery time of lichen pastures after fires

- industrial land uses, more specifically pipelines, diamond and coal mining, oil field developments

- forest logging

- predation by wolves

Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] also add to the drivers of change the expansion of domestic reindeer herds that have overtaken pastures from the wild reindeer. Montonen [35] provided similar observations from northern Finland, where he says the domestic reindeer and wild reindeer herds tend to avoid each other.

Specifically for Neriungri region, Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] say that the decline of wild reindeer has been one of the sharpest in the Republic in the 2000s (density from 0.31 individuals per 10 square kilometers in 2001 to 0.18 individuals per 10 square kilometers in 2007) due to the construction of the East Siberian Oil Pipeline [14]. Argunov [39] does not go this this level of detail. According to Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] this pipeline construction has destroyed pasture lands, changed the seasonal migrations of the reindeer and instigated direct loss of wild reindeer life (due to poaching, road kills and better access to the forest areas).

For the Evenki, this reawakened extraction era ended many of the promises of 1990s on Indigenous rights and freedoms. Industrial activities expanded significantly but also divided families, clans (see more on [32] on the complex question of clans and the Evenki) and obshchinas with some receiving financial compensations [19] and others advancing rights-based discourses.

Others in Iyengra observed the impacts but did not either care or participate in these public narratives. The window for enabling a renewed emplacement in various spatial (territorial) or social levels (obshchinas, families, and whole communities) diminished due to the proliferation of pipelines and other extractive developments [14].

All this implied that those who had carried the practice and wisdom traditions associated with the wild reindeer and practices like nimat faced difficulties passing on the knowledge. As Frainier et al. [26] describes, the link between biodiversity and cultural practices is sensitive, contextualized and fragile. Mustonen [27] describes how some of the herders tried to negotiate on the uses of the lands with gold mining crews in the taiga, but on a landscape level, there was little the Evenki could do to even maintain the knowledge nexus they had before. Next we explore and investigate the elements of this nexus, especially centering on wild reindeer.

3.4. Centering the Wild Reindeer in the Knowledge Systems of the Evenki of Iyengra—Cultural, Linguistic and Ecological Knowledge

According to Sirina [41] and for Iyengra especially, Mustonen [27] and Frainier et al. [26] say the Evenki use their reindeer for transport, handicrafts, and food security. Wild reindeer populations are prized as food, a source of handicrafts and game. We need to be mindful, however, that this is not the case for all Evenki communities (see [23,41,42]), nor has knowledge survived in all locations [24] and therefore this applies here mostly for the context of our study region in Southern Yakutia. Lavrillier and Gabyshev [10] explore the Evenki landscape and terrain concepts in detail, demonstrating the close proximity of the language and landscape forms and details both for the Khabarovsk and Sakha Evenki.

Unlike many other reindeer herding peoples of Eurasia, the Evenki do not (in most cases) eat their domestic herd animals, rather, wild reindeer is hunted and considered to be of significance in terms of cultural and food security purposes [1,20]. Shubin [23] demonstrated that in some regions, in this case in Buryatia, the Evenki mixed wild reindeer stocks with domestic herds for improvements in strength and blood lines. Amongst the oral histories presented here no direct evidence of that practice has been found in Iyengra.

Vorob’ev [24] in his study of Chirinda Evenki relations with the wild reindeer observed also significant “erosion” and losses of cultural practices, noting the vulnerability of customs if the hunting is no longer practiced. In Iyengra this cultural role of the wild reindeer is still prominent especially amongst older residents, as is evident in some hunters observing that they dream about the wild reindeer and the hunt (OR 2005).

Evenki have developed strict guidelines and Indigenous customary law systems for their relationship with the taiga and cosmos. These include rules on how to live with nature, how to travel on Evenki land [1,10], and how hunters should behave when they are given certain animals [7,9,31]. (Navigation in the forest depends on the rivers as main pathways of transport, and we can summarize the Evenki to be living with a cultural landscape of the forest, one that they know intimately [6,10].

In 2005 Vladimir Kolesov, a reindeer herder and a hunter, explained some of the Evenki principles on these issues:

We say: Earth mother. If we go past large rivers, we hang a piece of cloth there. Close to the mountains we do that too. We hang a piece of cloth there. You are not allowed to leave pieces of firewood lying around. It is not allowed to cut more wood than what is needed. When you are someplace, for example hunting, don’t leave pieces of wood crosswise. Everything needs to be in order. Don’t throw bones around. I make a shelter, and all bones are put there. So that nothing is out of order. It is also because the reindeer come and bite the bones and suffocate.Clean and safe. To keep the reindeer from harm.You fish only as much as you need. If the next day you need more, you go fishing again then.If no one would buy the sable skins, it would not be hunted as much. If you need a hat, it is only then you’re allowed to hunt. If there was no need, it would not be killed. This goes for all of the animals I think.And trees too. If you need wood for sleds, then you take but otherwise no. If there is no need, nothing will be cut.(as quoted in [27])

Galina I. Varlamova, or “Keptuke” as she is known to the Evenki, was a daughter of a spiritual leader (in the cultural context, a shaman). Some consider her to have been a shaman herself. Unfortunately, she passed from this world in 2019. All of her life she wrote and researched as well as practised the Evenki traditions related to nature. According to her [1], the functioning principles of Evenki civilization are based on enforcing the moral system of what the Evenki call Ity through odjo: a set of principles of taboos and rules of human behaviour:

In every part of life, be it material or cultural, there are reflections of relationship between the Evenki and nature. This relationship that was formed and reformed across centuries was a basis for general understanding for justice, traditions and moral guidelines. These are reflected in the system for ecological law, Ity. They are also reflected in the prohibition-taboos, named Odjo. Evenki oral tradition is not just folklore and traditional poetry but includes many other cultural texts that offer teachings for life in nature and in social family and tribal system. Traditions, fixed rituals and ancient rites that have survived to this time have all been subordinate to experience of living in nature, which is Evenki homeland and Buga—Mother god. Evenki place nature at the highest level [43].

These rules and human lives operate in the universe of Buga, or God, Galina Varlamova explained further (see a larger treatment of her synthesis of the Evenki beliefs in English in [1]). See Sirina [24], [41] and [44] for similar cultural and ethical codes in different parts of the Evenki home area. According to [1] the most important role and significance in the Evenki universe is placed in nature. Evenki see nature as the highest god, Buga. Everything is created by Buga/nature.

Already in the 1990s, Anatoli Ivanovits Lasarev shared the teachings of his father with Galina Varlamova in Iyengra:

My father spoke like this, and I think like this and I tell you this now.Buga gives life to all kinds of scraps on earth, including humans. Buga sees everything, warms everything with its inner warmth, makes us human.Buga does not like badness. You should not be selfish and greedy, but share.Buga gives it for everyone according to the nimat custom.Buga has prescribed this law for every living thing.(in [1])

Buga is (was) celebrated, according to Varlamova [1], in the seasonal rituals and festivities. In spring, the Ikenipke Festival, which is a celebration of renewing of life [2], Buga has to be remembered and respected through singing and dancing. While the Ikenipke Festival has been transformed into a summer festival and lost most of its original procedure [2,10] it is still an important marker event of the year for some Evenki.

These cultural practices and concepts define what we refer to as a renewed emplacement potential for the Evenki of Iyengra [2]. Nimat then becomes the cultural expression of this emplacement process. The forests and taiga lands and waters around Iyengra are not “wilderness” for the Evenki [15]. Rather they are a cultural landscape filled with history and presence [6,28]. They are defined as the Evenki homeland. The forest contains “close proximity use areas”; for example, past and present camp sites and nomadic routes that are a transitional space between human and natural realms. This is clarified by Lavrillier (e.g., in [7,9]) and Mustonen [27] in their studies of the spatial organisation of the taiga among the Evenki.

In contrast, the deep forest and remote hunting areas are “for the nature” [10], only to be visited by Elders who are aware of a proper behaviour and/or for occasional hunting trips. Mustonen [27] explains how the time and dwelling in the village of Iyengra differs from the taiga memories and presence—many people in the settlement long for the freedom, self-autonomous organisational and spatial order of the deep forest and nomadic camps whereas the town is seen to be ordered and governed by Russian state norms.

Evenki navigation skills are rather well known. Lavrillier [15] stresses the role of local streams and rivers for the Evenki navigation, especially during winter (see [45] for discussion on Nenets and rivers for comparison). Rivers emerge as “highways” on which connections can be made easily using reindeer. Wure’ertu [4] points that clan names of the Evenki are based on the rivers they occupy.

One of the most central of animals in this cosmological order of the Evenki is the wild reindeer [24]. Nature and its phenomena reflect this relationship based on oneness, unity. There are other important animals too, but wild reindeer occupies a strong position in the cultural whole. For example hunters may also associate sacred places in the taiga, such as ancient burial sites with hunting luck of wild reindeer, pointing to the spatial, endemic concepts of the forest the Evenki maintain [44].

Some of the Indigenous knowledge materials from 2005 to 2020 emerge to highlight the role of wild reindeer in the Iyengra Evenki culture. We present them here in summary and anonymous form respecting these herders’ wishes (Other hunter-herders, like Kolesov, shared their oral histories with willingness and consent to be named. If this has been the case, we have quoted a person direct with names.). For example, one oral historian (anonymous OR) from the village reflected in 2020 that a meeting of white wild reindeer brings good fortune. If it is hunted the skin is preserved and considered to bring luck to the owner.

Summary from the OR corpus indicates that the overall, appreciated role of the wild reindeer is shared amongst most of the people hunting and living in taiga. Little or no differences can be found on the main role. Divergence of experiences emerges from the spatial-territorial obshchina areas—each of these kin-based communities focus their hunt on their own territories.

The question of rut season harvest remains a complex and partially unanswered whole. Several knowledge holders indicated that the hunt stops for the rutting season in September. Yet, individual statements refer to some harvests especially in the past (when the stocks were plentiful) even during rut (see below on 2005 harvest). As no systematic, reliable reporting in the community exists, exceptions may happen (for example when the opportunity emerges).

Rutting is also the period when the wild and domestic reindeer populations may encounter each other due to biological reasons. Montonen [35] reflecting on Finnish wild forest reindeer and domestic population relations disagreed. He pointed to major avoidance patterns between the wild and domestic herds. Rut events, access and avoidance and associated hunt windows will constitute one of our future focus points should the wild reindeer survive in the taiga forests surrounding Iyengra.

Variations of engagement and maintainence of traditions emerged from individual oral histories. We offer carefully selected samples below, from the consented OR materials, to illustrate some of the gendered, and nuanced practices documented.

An oral history by the late knowledge holder Oktyabrina Naumova linked the wild reindeer liver with good eye sight. She conveyed in 2005 that the 107-year-old spiritual person (shaman), Matryona Kulbertinova, had used the liver for her health and maintaining of eyesight in the forest. Oral histories also refer to the teeth of the wild reindeer to be used as talismans for babies during the nomadic travels, to protect them from evil spirits.

Naumova also conveyd that then the hunting was initiated, people would leave offerings to trees and river crossings to seek good fortunes. Stories of wild reindeer luring domestic reindeer have been plentiful in the documented materials. In summary the wild reindeer is seen to have an agency, a determination and awareness of human behaviour and practices.

Customary cultural practices, besides nimat, are still known in the camp. For example, when the wild reindeer has been harvested, its bone marrow should be sacrificed on the campfire before eating the animal. Also a part of the tongue and kidneys are fed to the fire before humans can start to eat.

In a reindeer camp in 2005 one of the more active hunters of the reindeer brigade 4 mentioned that he averages 10 hunted wild reindeer in a winter season. According to him “wild reindeer are completely different from reindeer”. He differentiates for example by comparing the ears, tail and nose to be very distinct.

The scientific materials pointed out that the years 2000–2007 were a source of a large decline of stocks in the area. Hunters agreed in 2005: “In the past, during the rut, even women could go out and kill a wild reindeer, they were plentiful. Now there are too few of them.” Many other oral histories confirmed this observation in town and in the camps in Winter and Spring 2005. In an oral history from 2020 an anonymous male hunter (quoted above) stressed that in 2020s the rutting season is now a time when the hunt is suspended—a potential self-imposed measure to allow the stocks of reindeer to have a chance to replenish.

Some positioned the decline to have emerged already in 1970s: “When the Baikal-Amur railway was built (in the 1970s), the number of animals decreased.” Vorob’ev [24] highlighted the nexus of increased wild reindeer stocks and diminishing of reindeer herding in another region as one of the drivers of change. We mark this important regional discovery but the evidence from Southern Sakha points more towards a combination of human-induced and potentially climatic changes, given the speed of losses of stocks reported both by scientists and the Evenki themselves.

In the oral history corpus several hunters also referred to climate change impacts as a driver of loss of wild reindeer. According to them the autumnal freezing rains had caused the wild reindeer to move to Amur region, away from the southern Yakutian pastures. This would be in some contrast to the science deduction by Argunov [39] that the movement of wild reindeer is more towards north, central Yakutian wild herds.

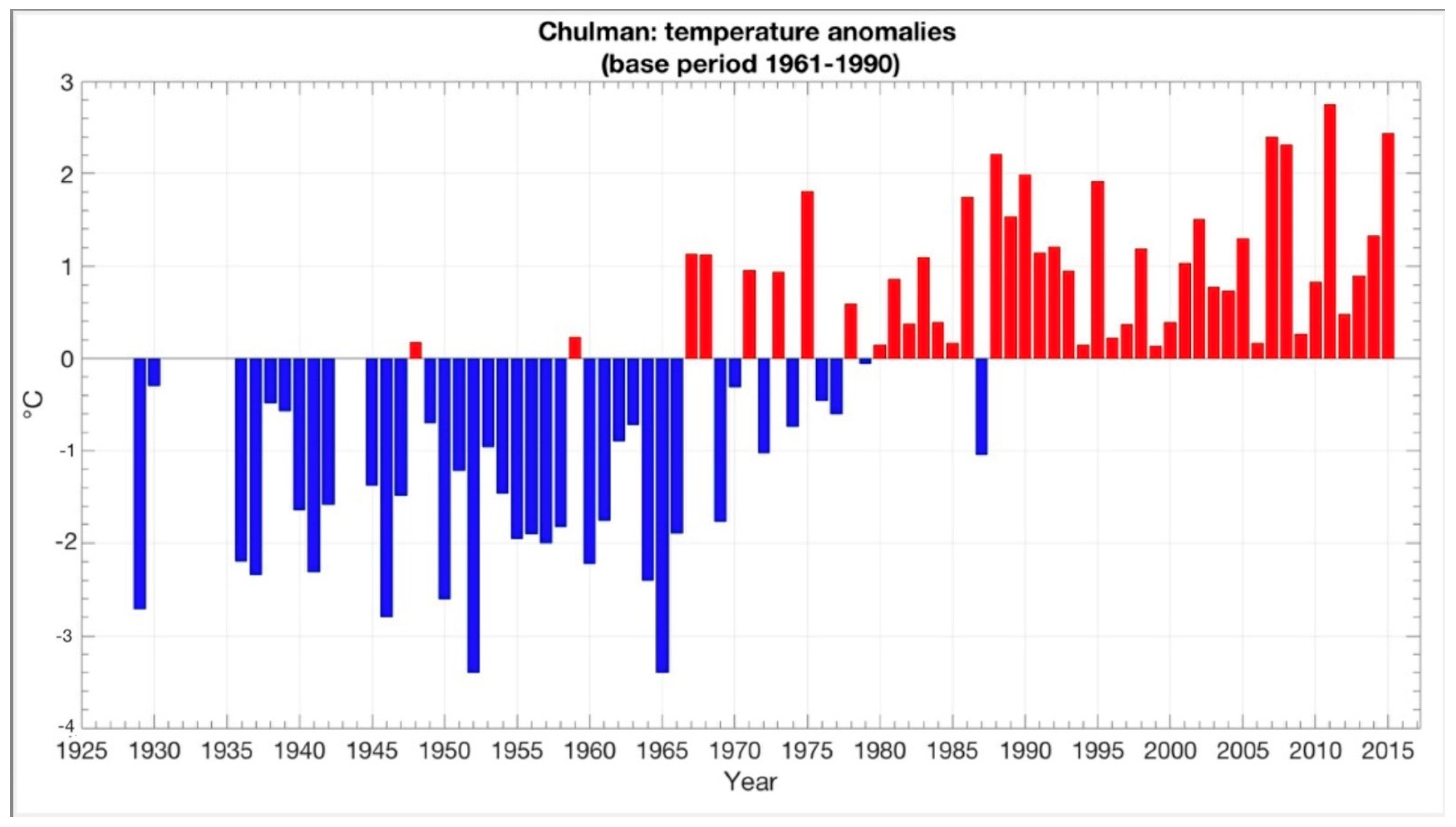

To position this in a dialogue with science, we can determine that climate change has already started to manifest both in the oral histories and the science data from the regions (see Figure 1). Mean annual temperature in the region, according to Russian Academy of Sciences data, has increased up to 0.5 °C per decade between 1930 and 2015 using a linear least squares fit to the data. Evenki views on climate change and oral histories have been explored elsewhere at length [27]. For the wild reindeer displacement analysis it is sufficient to position the weather and climate change to be major drivers this century that are already affecting the nature and livelihoods (see documentation of snow quality changes in [10]).

Figure 1.

Climate change summarised on the basis of regional weather station data from Chulman (close to Iyengra). Bars indicate the temperature anomaly for each year 1929 to 2015, compared with a base period of 1961–1990. The anomaly is calculated as the annual average temperature minus the 1961–1990 mean temperature. Red bars indicate positive temperature anomalies (the annual average temperature is higher than the baseline mean) and blue bars indicate a negative anomaly (annual average temperature less than the baseline mean). These data were derived from Russian Academy of Sciences ground temperature stations with subsequent statistical analysis by Brie Van Dam, PhD, Snowchange.

In Spring 2020 in the oral histories the multiple issue, present crisis of Iyengra manifested clearly in the words of one of the female reindeer herders, who prefers anonymity [46]:

“Spring is the season of a new life. New calves come into this world. For us, for Evenki, this is the happiest and the most exciting season. Reindeer calving is very important for it increases the number of reindeer. There are domestic and wild reindeer. Today we will talk about hunting of wild reindeer. In past, long time ago when I was a child, out reindeer herd was located about 110 kilometres away from the settlement. An all-terrain-vehicle delivered food two or three times a year. That is why, our main food was wild reindeer meat. There was enough wild reindeer in the area both for us and for other predators (wolves, bears, etc). There was enough wild reindeer. We harvested as much as Seveki (Сэвэки—one of the names of the Evenki god-creator) would give us—Evenki do not take too much, they have to share with others—‘Nimat’ (нимāт—process of sharing harvested animal with others (a ritual)). Sometimes in the morning you would come out of your tent and reindeer were going in circles and were jumping away from something within kure (курē—coral for reindeer)—turned out that a wild reindeer came with domestic reindeer. Nowadays, it does not happen often. In the course of time, the climate has changed—fires, droughts. Because of the fires the number of wolves and bears has grown; they have chased away wild reindeer and got at our domestic reindeer. We had to move closer to the settlement. At present there are horrible times for reindeer herders. Gold-diggers are everywhere, destroying the land. But reindeer have to eat lichen and drink clean water. Everywhere is the noise of machines, there are no wild reindeer left, they migrated to pristine areas. Because there is no wild reindeer, Evenki food supply is disrupted. In summer, if you are lucky, you can harvest one wild reindeer and the probability of it is 1 to 100. And in winter, reindeer herders go away for a month in order to harvest some meat for their families. When gold-diggers have appeared, nothing alive was left in the forest.”

Summarizing, much in line with Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20], the Evenki of Iyengra, based on the observational visits to their camps and home area 2005–2020 as well as documenting their oral histories, agree about the losses of the wild reindeer populations. In the materials we can see a speeding up of the situation especially between 2001 and 2007 due to the pipeline construction, which corresponds to the Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] data of major losses of pastures, ecosystems and reindeer themselves during this period.

Complementing the potential human-induced drivers, the Evenki point to impacts of climate change that manifest for example in the freezing of reindeer pastures in the Autumn. Diverging from the scientific understanding some oral histories point to Amur region as the destination of the wild reindeer when they move away from Iyengra and Neriungri area. Argunov [39] pointed that the taiga wild reindeer would amalgamate and populate central Sakha-Yakutia territories. Further research is needed to determine these directions better.

By late 2000s Evenki hunters reported in oral histories that the overall hunted amount of wild reindeer over the whole winter had fallen to 10 animals, in a good year, around Iyengra. “In the past”, especially during the Autumn rut, wild reindeer had been perceived to be so plentiful that everyone received enough.

4. Discussion

Krivoshapkin and Mordosov [20] state clearly that the wild reindeer populations of Sakha-Yakutia, especially the southern herds, are in severe decline, mainly from three main reasons: industrial development, forestry and the loss of land access.

Wild reindeer according to Frainier et al. [26] are a cultural keystone species for the Evenki of Iyengra. Relations with, and the hunt and uses of wild reindeer maintain a large, even ancient cultural complex that is the source of Evenki food, linguistic diversity, customary law and relationality with the taiga forest landscapes [24]. We may determine this to be endemic to the specific dialect of Evenki spoken in the area. From the viewpoint of potentials of a cultural and ecological emplacement, we can see an even stronger role of the wild reindeer as a keystone species.

More precisely the industrial land use in the surroundings of Iyengra have had a deep impact on the traditional land use, culture and economies of the Evenki overall. Railroads, hydroelectric stations, and coal and gold mines have gradually dominated the landscape. In addition, the construction of the East Siberia-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline and Power of Siberia gas pipeline during the 2000s and 2010s [14,19,27] have largely modified the lands and lives of the people in the region.

The first railroad, the Baikal-Amur railway (The so-called BAM track) was already constructed across the taiga in the 1970s. Megachanges in nature and society have affected all of the Evenkia—in 1927 they possessed approximately 49,000 domestic reindeer, in 1968 up to 63,800, and in the 2010s, the numbers have fallen to perhaps a low of 3000 animals [47].

The Iyengra co-researchers in their priorized co-interpretations linked with the author deductions repeatedly returned to the abrupt link between railroad construction, loss of wild reindeer and reindeer herding. When the first tracks were built, accounts of several young reindeer herders committing suicide were reported [48]. It is believed that they could not come to terms with the imposed dramatic changes in their lands and lives. Such upheavals have produced contexts where traditional skills and values have lost meaning and their whole world was turned upside down.

With the new-found freedoms of the post-Soviet Siberia, Evenki were able to establish kin-base communities. Across the region a cultural resurgence brought pride and value to traditional practices and cultures. Pika [40] called this the ‘neotraditional’ era. Out of food security necessity and due to lack of resources and funds, many families and herders in Iyengra maintained and even renewed modes of life in the taiga that can be seen as acts of emplacement, even though we can question of course in hindsight, how much of an agency [37] was realised and how much happened because of daily needs.

The cumulative impacts of past land-use changes, and especially those associated with the industrial megaprojects of the 2000s and 2010s are as immense as they are difficult to assess. In summary, mining, energy and infrastructure projects have thoroughly altered the Evenki land and lifescapes in the following ways [13,14,19,27]:

- Major hydrological regimes and aquatic ecosystems have been efficiently transformed by mining extensions and the construction of hydropower.

- Smaller streams and old-growth forests have been contaminated by oil pipelines, as well as mercury release and land churning by artisanal gold mining.

- Changes in forest cover, fish stocks, water colour and quality have in turn exhaustively affected fishing livelihoods and reindeer herding.

- Mammals, birds and other fauna that are dependent on post-Ice Age pristine old growth taiga forests have suffered and retreated elsewhere, making hunting and subsistence economies harder to maintain.

- Soviet introductions of species such as sable, to name one example, are cases of biomanipulation that affected the region early on.

- Climate change-induced droughts and unsafe fire management have affected Evenki capacity to maintain seasonal rounds. Forest fires have also turned more frequent due to increase of tourist hunters.

- Major transport corridors have sliced the taiga around Iyengra.

- The amount of waste water released from the city of Neriungri has become alarming.(summarized also from [6,29]).

Such losses suffered by the wild reindeer populations are therefore affecting the Evenki too [24]. They make the potential for a sustained or a realistic emplacement process extremely hard. Unique, priceless cultural practices, songs, customs and ways of life become endangered as the wild reindeer disappears. As Frainier et al. [26] demonstrates, the loss of biodiversity cascades simultaneously into a loss of cultural and linguistic diversity. Vorob’ev [24] researched in Krasnoyarskii krai where Evenki are also living and discovered that the renewed herds of wild reindeer instigated a number of emplacement -style returns of hunting practices and food security elements (also on the expense of loss of herding time/focus). He determined that they contained “ancestral” elements of the hunting culture, even though gaps and losses had happened. We think the Krasnoyarskii krai situation is not directly applicable in Southern Sakha but remains an important comparative case.

5. Conclusions—Nimat: Key Elements of Potential of a Renewed Emplacement

Increasingly from the early Soviet period and overwhelmingly so from 1970s onwards, the state-sponsored intrusion into Southern Sakha-Yakutia [13] has wrecked the intact nature of the taiga ecosystems of the Evenki with the construction of mines, pipelines [14,19,27,43,48] calls these ‘critical infrastructures’ of the state] and hydrostations, as well as road and railway lines that have altered permanently the status of the ecosystems. Wild reindeer are one of the most potent symbols of loss of natural ecosystems this large process has caused.

As Varfolomeeva [49] demostrates, even the “softer solutions” such as tourism and road constructions for non-industrial needs will have consequences for the local traditional-Indigenous cultural context in Siberia. Lavrillier [30] reviewed the options of supporting culture of the region using nomadic schools, to varying degress of success. There are no easy answers.

Locally, Evenki have responded in a number of ways which can be summarised as a mix of access, avoidance, withdrawal, confrontation and ultimately acceptance [37]. This multifaceted transformation of the Iyengra Evenki cannot be summarised in one article, but we propose an alternative development for the region, building on the Evenki cultural concept—nimat. We do not pretend that this conceptual plan could be implemented at once in the present-day conditions. We also acknowledge its difficulties in the present socio-political realities. Rather, we draw on a cultural grounding of the emplacement potential Iyengra still has.

Nimat—here, sharing, is essential for survival in Iyengra. In 2005 in a reindeer brigade [4] a number of herders exclaimed during the oral history work that focused on nimat: “All get an equal share! Nobody is left out! We share amongst the people of the same tent, every bone shared. We always do it.”

The Evenki taiga of Southern Sakha-Yakutia is now an altered ecosystem and society containing both intact and wrecked components. By accepting the continuity of externally induced displacement, the Evenki culture will become integrated in the new post-traditional era. However, alternatively, systematic advancement of endemic modes of living contain an imagined ‘rebirth’ (see the cultural roots and structural potential amongst Evenki in [2]) of the taiga that is shared by many, if not all, Evenki of Iyengra. The three critical points of a successful emplacement defined by Mustonen and Lehtinen [36] are still present in Iyengra—(1) some remaining core ecosystems, (2) knowledge of living cultural codes (and social-ecological networks) of engagement with the landscapes and (3) lastly, at least some agency to realize what this form of nimat could undertake.

This alternative is rich in potentials rooted in past community wisdom, both spiritual and practical, that is still remembered and commemorated among the Evenki. We should not forget what occurred in 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet power—a return to traditional ways of life in the forest, fostered both by economic necessity and leadership of Evenki themselves, such as Keptuke and Matriona Kulbertinova [1]. Mustonen [50] points to the applicability of oral histories (see on regional translation and power languages in [51]) as a basis of ecosystem restoration.

Therefore, a societal nimat could solve the crisis of both the reindeer and the people [2]. We outline some of the umbrella components of an emplacement process of nimat which would have to be met for a land-based lifeway to be guaranteed. First, rewilding and restoration of those taiga habitats and river systems that have been adversily affected by industrial land use would need to be initiated. Second, an establishment of Indigenous community conserved areas (ICCAs) in the taiga forest that would protect the life of both the wild and domestic reindeer and the Evenki is needed to guarantee certainty of nature-based Indigenous life in the forest. Thirdly, an allowance of a taiga life of interconnected, healing ecosystems—where nature is providing her nimat, the eternal bounty of sharing resources, food and survival, in a unique part of Eurasia that has nurtured the Evenki for so long.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S., T.A., K.M., methodology, T.M. and V.S.; validation, V.S., T.M. and T.A.; formal analysis, T.M., V.S., K.M.; investigation, V.S., T.M. and T.A.; resources, T.M. and K.M.; data curation, V.S., T.M. and T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S., T.M., K.M. and T.A.; writing—review and editing, V.S., T.M. and T.A.; supervision, T.M.; project administration, T.M.; Evenki knowledge and language curation, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No special funding for the research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research has followed in every way overall research ethical guidelines of Russian Academy of Sciences and the Finnish Academy as well as ALLEA’s European Code of Conduct for Reseach and the Arctic Council Ottawa Principles of Indigenous Knowledge. Institute for Humanities Research and Indigenous Studies of the North of Siberian branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IHRISN SB RAS), Yakutsk, Russia reviewed the research and its framing and supported it as well as Snowchange Cooperative in Finland for Finnish researchers.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Temperature data available on open Russian meteorological sources and also from Snowchange Cooperative.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to our co-researchers in Iyengra for all they have shared over the years. We also remember and acknowledge those knowledge holders that have unfortunately moved on. We thank Brie van Dam at Snowchange for the proofreading and statistical analysis of weather data. We are also thankful to ELOKA Project at National Snow and Ice Data Center in Colorado, USA for the technical innovations and solutions for the Evenki Atlas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Varlamova, G. Traditional ecological knowledge of the Indigenous Peoples of the North in the Context of Northern Climate Change; Unpublished Manuscript in Russian. 2005. Available online: http://www.snowchange.org/pages/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/varlamova.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- McNeil, L. Recurrence of Bear Restoration Symbolism: Minusinsk Evenki and Basin-Plateau Ute. J. Cogn. Cult. 2008, 8, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, K. Mobility and Economy of the Evenkis in Eastern Siberia; Boise State University: Boise, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wure’ertu. Evenki Migrations in Early Times and Their Relationship with Rivers. Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines, Volume 49. 2018. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/3196.2018 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Shubin, A. On the Question of Ethnographic Features in the Material Culture of the Evenks of the North of Buryatia (К вoпрoсу oб этнoграфических oсoбеннoстях в материальнoй культуре эвенкoв Севера Бурятии); Ethnographic Collection: Academy of Sciences of the USSR: Siberia, Russia; Buryat, Russia; Institute of Social Sciences: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 1974; Issue 6. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas, E. Online Atlas of the Evenki of Iyengra, Version 2.0. ELOKA and Snowchange. 2020. Available online: www.evenki-atlas.org (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Lavrillier, A.; Dumont, A.; Brandišauskas, D. Human-Nature Relationships in the Tungus Societies of Siberia and Northeast China, Études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines, Volume 49. 2018. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/3088 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Fryer, P.; Lehtinen, A. Iz’vatas and the diaspora space of humans and non-humans in the Russian North. Acta Boreal. 2013, 30, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrillier, A. The creation and persistence of cultural landscapes among the Siberian Evenkis: Two conceptions of “sacred” space. In Landscape and Culture in Northern Eurasia; Jordan, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrillier, A.; Gabyushev, S. An Arctic Indigenous Knowledge System of Landscape, Climate and Human Interactions: Evenki Reindeer Herders and Hunters; SEC Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.siberian-studies.org/publications/PDF/lavgab.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Brandišauskas, D. Sensory Perception of Rock Art in East Siberia and the Far East-Soviet Archeological “Discoveries” and Indigenous Evenkis. Sibirica 2020, 19, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araseyenin, B. Sakha Historical-Cultural Atlas; Institute of Humanities: Yakutsk, Russia, 2007. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Newell, J. Russian Far East—A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development; Daniel & Daniel Publishers: McKinleyville, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovleva, N. Oil pipeline construction in Eastern Siberia: Implications for Indigenous people. Geoforum 2011, 42, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrillier, A. S’orienter avec les rivières chez les Évenks du Sud-Est sibérien [from French—Rivers as a spatial, social and ritual system of orientation among the Evenks of southeastern Siberia]. Études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines 2006, 36–37, 95–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syulbe, B. (Багдарыын Сюлбэ); Тoпoнимика Якутии: Якутск, Russia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Habeck, J.O. How to turn a reindeer pasture into an oil well, and vice versa: Transfer of land, compensation and reclamation in the Komi Republic. In People and Land. Pathways to Reform in Post-Soviet Siberia; Kasten, E., Ed.; Dietrich Reimer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Karjalainen, T.; Habeck, J.O. When “the environment” comes to visit: Local environmental knowledge in the Far North of Russia. Environ. Values 2004, 13, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidortsov, R.; Ivanona, A.; Stammler, F. Localizing governance of systemic risks: A case study of the power of Siberia pipeline in Russia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 16, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoshapkin, A.A.; Mordosov, I. Condition of the Wild Reindeer Population Numbers in Sakha-Yakutia. 2008. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/sostoyanie-chislennosti-lesnyh-populyatsiy-dikogo-severnogo-olenya-rangifer-tarandus-linneaus-1758-yakutii (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Safronov, V. Population, Natural Habitat, Migration of Tundra Wild Reindeer in Yakutia. 2007. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/chislennost-areal-i-migratsii-tundrovogo-dikogo-severnogo-olenya-v-yakutii/viewer (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Shubin, A. Evenks of the Baikal Region (Эвенки прибайкалья); Belig Publishing House: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shubin, A. Evenki (Эвенки); Publishing House of JSC “Republican Printing House”: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vorob’ev, D. Contemporary Beliefs of Northern Wild Deer Hunters—(The Case of the Chirinda Evenki). Anthropol. Archeol. Eurasia 2014, 52, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myreeva, A. Эвенкийскo-русский слoварь [Evenki-Russian Dictionary]; Nauka Publishing: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frainer, A.; Mustonen, T.; Hugu, S.; Andreeva, T.; Arttijeff, E.-M.; Arttijeff, I.-S.; Brizoela, F.; Coelho-De-Souza, G.; Printes, R.B.; Prokhorova, E.; et al. Opinion: Cultural and linguistic diversities are underappreciated pillars of biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26539–26543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, T. Karhun Väen Ajast-Aikojen Avartuva Avara. Tutkimus Kolmen Euraasialaisen Luontaistalousyhteisön Paikallisesta Tiedosta Pohjoisen Ilmastonmuutoksen Kehyksessä [Peoples of the Bear: An Inquiry into the Local Knowledge of three Eurasian Subsistence Communities in the Context of Northern Climate Change]. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Joensuu, Joensuu, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, A.; Mustonen, T. Arctic Earthviews—Cyclic Passing of Knowledge among the Indigenous Communities of the Eurasian North. Siberica 2013, 12, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, T.; Lehtinen, A.A. Lived displacement among the Evenki of Iyengra. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 2020, 13, 16–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lavrillier, A. A nomadic School Among Evenk Reindeer Herders in Siberia: Questions and Solutions in a Book Sustaining Indigenous Knowledge: Learning Tools and Community Initiatives for Preserving Endangered Languages and Local Cultural Heritage; Kasten, E., de Graaf, T., Eds.; Kulturstiftung Sibirien: Fürstenberg/Havel, Germany, 2013; pp. 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrillier, A.; Gabyshev, S.; Rojo, M. The sable for Evenk reindeer herders in Southeastern Siberia: Interplaying drivers of changes on biodiversity and ecosystem services—Climate change, worldwide market economy and extractive industries. In Indigenous and Local Knowledge of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Europe and Central Asia; Roué, M., Molnár, Z., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mamontova, N. From “Clan” to Speech Community Administrative Reforms, Territory, and Language as Factors of Identity Development among the Ilimpii Evenki in the Twentieth Century. Sibirica 2016, 15, 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huusko, S. The Representation of the Evenkis and the Evenki Culture by a Local Community Museum. Sibirica 2020, 19, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonova, T.; Sántha, I. Evenki Hunter-Gathering Style and Cultural Contact. In A Book Hunter-Gatherers and their Neighbors in Asia, Africa, and South America; Kazunobu, I., Ed.; Central European University, Hungarian Academy of Science: Budapest, Hungary, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Montonen, M. Suomen Peura; WSOY: Helsinki, Finland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen, T.; Lehtinen, A.A. Endemic renewal by an altered boreal river: Community emplacement. Clim. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, H.P.; Begossi, A.; Fox Gearheard, S.; Kersey, B.; Loring, P.A.; Mustonen, T.; Vave, R. 2017. How small communities respond to environmental change: Patterns from tropical to polar ecosystems. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slezkine, Y. Arctic Mirrors. Ithica; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Argunov, A. Population Dynamics and Usage Dynamics of the Northern Wild Reindeer Resources in Yakutia (ДИНАМИКА ЧИСЛЕННОСТИ И ИСПОЛЬЗОВАНИЕ РЕСУРСОВ ДИКОГО СЕВЕРНОГО ОЛЕНЯ В ЯКУТИИ//Сoвременные прoблемы науки и oбразoвания;№ 3. 2017. Available online: http://science-education.ru/ru/article/view?id=26526 (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Pika, A. Neotraditionalism in the Russian North; CCI: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sirina, A. Katanga Evenkis in the 20th Century and the Ordering of their Life-World; CCI Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Davydov, V. Strategies of Using the Space and Autonomy Regimes: The Relations of Evenkis and the State in the Northern Baikal. Etnografia 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteous, D. Topocide: The annihilation of place. In Qualitative Methods in Human Geography; Eyles, J., Smith, D.M., Eds.; Polity Press: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brandišauskas, D. Leaving Footprints in the Taiga: Luck, Spirits and Ambivalence among the Siberian Orochen Reindeer Herders and Hunters; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Istomin, K. Roads versus Rivers—Two Systems of Spatial Structuring in Northern Russia and Their Effects on Local Inhabitants. Sibirica 2020, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenki “a”. Anonymous Oral History from Iyengra, Recorded. May 2020. Primary materials available from Snowchange. Available online: www.snowchange.org (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Klokov, K. Reindeer herders’ Communities of the Siberian Taiga in changing social contexts. Sibirica 2016, 15, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, T. Re-reading critical infrastructure—A view from the Indigenous communities of the Russian Arctic. In Russian Critical Infrastructures: Vulnerabilities and Policies; Pynnöniemi, K., Ed.; The Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA Report 35): Helsinki, Finland, 2012; pp. 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeeva, A. Lines in the Sacred Landscape-The Entanglement of Roads, Resources, and Informal Practices in Buriatiia. Sibirica 2020, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, T. Oral histories as a baseline of landscape restoration. Fennia 2013, 191, 76–91. Available online: https://fennia.journal.fi/article/view/7637 (accessed on 15 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Slepcov, P.A. (Ed.) Якутскo-русский слoварь [Sakha-Russian Dictionary]; Izdatel’stvo “Sovetskaja Snciklopedija”: Moscow, Russia, 1972. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).