Abstract

This work studied the efforts of the Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage in Cyprus to explore how effectively the TCCH applies diplomatic relation-building efforts towards cultural heritage management and how this can be used to construct a bridge to a process of sustainable development of social relations and heritage use in Cyprus. The Committee’s efforts demonstrate community heritage diplomacy and civil heritage diplomacy, employed by the two largest communities of the island as they attempt to build relations with each other and other minor communities across the border via various heritage practices, and public heritage diplomacy, which is employed by the authorities of each side via the Committee to influence the public of the other side. The Committee employs these forms of heritage diplomacy via a language of cooperation and by bridging gaps in and crossing borders for collaboration, so as to transfer knowledge, values, and experience, and to build trust with institutions and communities. The significance of the study lies in illustrating that the technical and collaborative successes of the Committee via application of the determined types of diplomacy may be successfully applied for a sustainable approach to build relations and confidence under ideologically and politically strained circumstances in Cyprus.

1. Introduction

The immovable heritage of and in Cyprus and the various relations that have revolved around it throughout the tumultuous history of the island have been a testament to the importance of said heritage to locals. They have used it to unify and to divide, to promote close relations and to maintain conflict between individuals and groups. No longer a colony under the rule of the British Government since 1960, a newly independent Cyprus harbored a less than stable political and social environment, as ethnically Greek and Turkish Cypriots clashed in a fight for governance of the island. Greater powers the likes of the United Kingdom took a hand in promoting this clash for their own political agendas [1,2]. The locals, in the meantime, clashed with each other on an ethno-political basis, with the active negligence, repurposing, and destruction of the others’ heritage acting as a tool of war [3]. In 1974, the penultimate year of separation of the island into two parts, the Turkish army landed in the north with the stated intent to protect Turkish Cypriot from the Greek Cypriots. The Turkish Cypriots, theretofore, lived in mingling with the Greek Cypriots and later, as clashes worsened, in alcoves dispersed throughout the island. As of 1974, the island is divided into roughly a third of the island in the north, the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), and two thirds south, the Republic of Cyprus (RoC), as well as a UN administered Buffer Zone separating the two areas (Figure 1). While Turkish Cypriots reside in the north and Greek Cypriots in the south, their mutual immovable heritage has remained interspersed throughout the island and has over the years witnessed vandalism, neglect, re-purposing, and destruction [4,5,6,7,8]. Despite the continued division and failed attempts at reunification, known as the Cyprus Problem, the border is slowly opening up, seeing an increase in checkpoints and an ease of crossing for touristic purposes [9,10,11,12]. After the division of 1974, heritage professionals of both sides almost immediately turned towards finding ways of cooperation with the purpose of preserving as much heritage as they could [13,14,15]. These efforts first led to the Nicosia Master Plan (NMP), which involved immovable heritage preservation and sustainability studies of places of historical heritage like the Nicosia city walls and Famagusta city, and other cross border heritage-related preservation, maintenance, and sustainable urban development research efforts, thus demonstrating that heritage related activities could act as a bridge across the divide [16]. These first steps led to the foundations upon which the Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage (TCCH) was created. Today, TCCH focuses not just on cross-border preservation and management of cultural heritage, but on doing so for sustainable development of social and diplomatic relations between the locals of the island as a whole.

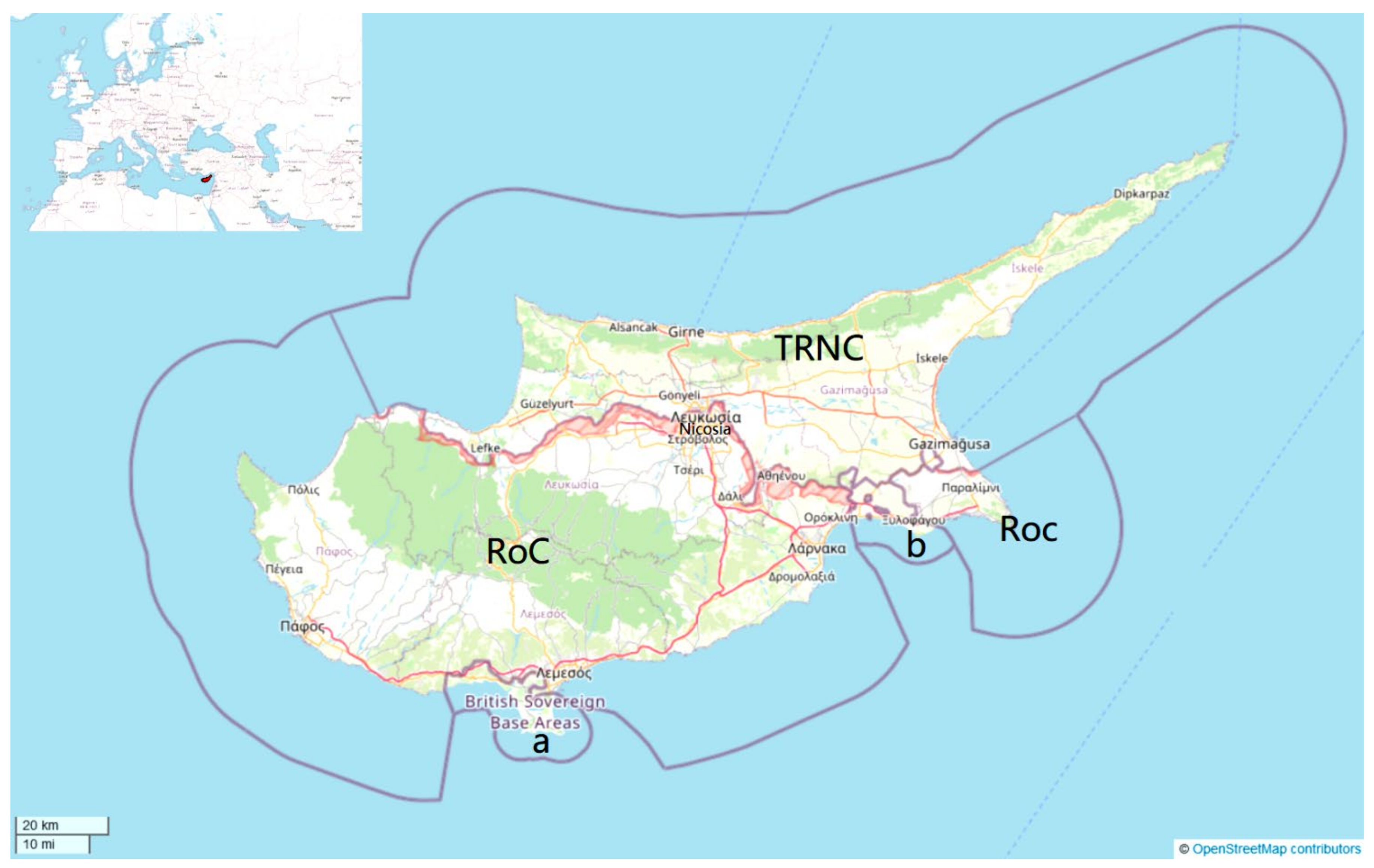

Figure 1.

Map of Cyprus demonstrating the division; the area shaded in red is the UN Buffer Zone. The two areas labeled a and b are British military Zones. Adapted by the authors from open source material [17]. © OpenStreetMap contributors. Copyright: https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright (accessed on 24 October 2021).

The discussion of cultural heritage management in relation to sustainable development is emerging, addressing how the management of cultural heritage assets could contribute to the process of sustainable development [18,19,20]. The literature on sustainable development is vast, but in essence proposes adopting cultural heritage management as an essential approach to deal with social, economic, and environmental issues of sustainability [21,22]. Recently, the role of cultural heritage management in transnational diplomacy, and especially serial nominations of UNESCO World Heritage status, has demonstrated the critical role of heritage in international relations and diplomacy [23,24]. Cultural heritage practices of cultural heritage internationally create a common set of development goals for all communities in different countries.

The problem we address in this paper is the relationship between the practice of international cultural heritage management and sustainable development, specifically heritage diplomacy as an attempt to build relations across borders via various heritage practices. Cyprus has much to offer in terms of the development of heritage diplomacy throughout the island’s modern history. This development has occurred via practical application and on a theoretical level that can contribute to the way in which cultural heritage is perceived and conceptualized by national, regional, and local governments. Consequently, this impacts how local communities associate themselves with heritage and other groups across the border.

This paper also focuses on whether heritage diplomatic relation-building efforts can be applied to finding sustainable solutions to the Cyprus Problem, bridging a seemingly inflexible and stagnant divide between cultural, ethnic, and religious groups on the physically divided island. Answering this question required determination of how the current status of heritage diplomacy in Cyprus has translated into management of cultural heritage assets on both sides of Cyprus.

2. Exploring the Roles of the Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage in Cyprus

Cyprus has a plethora of heritage elements passed down from generation to generation. These elements have played a significant role in the formation of individual and national identity and in the ethnic conflict that has caused an ongoing social, economic, and geopolitical divide between Greek and Turkish Cypriots (at the expense of minority groups such as the Maronite Cypriots) and thus between the RoC and the TRNC [3]. This has made heritage an indelible component of international diplomatic relations with such nations as Greece and the Republic of Turkey and of domestic intercommunal relations. Heritage diplomacy is a relatively new term that encompasses a variety of formal bi- and multilateral connections revolving around heritage governance [23]. These connections are established, developed, and maintained with heritage, and the practices and dialogues involving it. The heritage acts as either a core element or a practical resource in the power-exerting political, economic, and social strategies of states, international governmental and nongovernmental organizations, and groups of like-minded individuals. In Cyprus, such heritage practices and dialogues are wholly diverse. They include but are not limited to the excavation, preservation, conservation, maintenance, etc., of archaeological sites and unique cultural objects; the re-purposing and gentrification of war-torn buildings, land ownership disputes, and redevelopment for tourism, trade, and other economy-centered actions; politicization and the resulting palpable effects on tangible heritage; illicit and contested practices for the manipulation of nationalist ideals, etc. [4,5,6,7,8,13].

This plethora of themes and activities involving and revolving around heritage has presented fertile ground for a study of the complex role heritage has played and continues to play in the diplomatic affairs of Cyprus—as the following demonstrates, though in no way exhaustively and with invitation for further research. Within a chronological context of the history and current state of affairs in Cyprus, this paper explores the actions and motivations of a specific heritage-focused organization, the TCCH, to determine the specific nature of heritage diplomacy in Cyprus, how effective it has been over the years, and its possible relation to sustainable development in the future.

Some of the most prominent examples of cultural immovable heritage in Cyprus are ancient sites and relics, such as the UNESCO World Heritage site Choirokoitia, the Nicosia city walls, the Famagusta complex, and war-torn buildings and structures, such as those located in the Buffer Zone. The latter type of heritage has been contested, with issues of ownership, maintenance, history, etc., continually arising, as it is modern heritage created by conflict [13]. The island boasts a rich cultural heritage composed both of objects and sites once belonging to empires and republics long extinct. This heritage has been under a variety of governance systems dependent on the authorities once in power, but who now have limited say in the relations locals have with heritage. This is seen in the case of the imperial authority during Cyprus’ colonial time under Britain, which influenced the Ottoman Waqf institution and traditions of heritage and monument maintenance in Cyprus [25]. Cyprus is further rich in cultural heritage elements that continue to be used by modern-day inhabitants who focus on celebrating their own heritage in opposition to the “other.” This latter aspect is specifically seen in the case of the ethnopolitical clash between the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. Studies of demographic changes in Cyprus (predominantly the North) demonstrate a highly politicized cultural identity on the island that has affected attitudes towards heritage [26]. This has been done primarily in the form of purposefully perpetuated ambiguity of demographics data by authorities with the intention of altering the perception of the island itself as the rightful property of specific ethnic groups, actions that result in systematically altered views of what constitutes heritage and to whom it belongs, with an expected significant effect on the identity formation of future generations. The former type of heritage has been affected by this very same conflict, with ancient sites being neglected, accidentally damaged, and/or destroyed systematically [3]. Research literature on Cypriot heritage has revolved around the issues that are the result of ethnic and political conflict and the division of the island in 1974; examples include the aforementioned case of war heritage in the Buffer zone, the Armenian Church of Famagusta undergoing conservation under strained legal circumstances, various religious centers succumbing to issues of heritage crime, and the disparities between the South and the North in attitudes towards and efforts of conservation and maintenance [3,15,27]. A key element in this conflict is the nationalist views that are divided as a result of long-term focus on Greece and Turkey for political and ideological support [28]. This is a key element of social affairs on the island, as Greek Orthodox or Latin and Turkish or Muslim heritage elements are important to Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, respectively. The elements boost nationalist feelings along cultural, ethnic, religious, etc., divides. This is opposed to being united in a single nationality, Cypriot, and with widespread acceptance of the diversity of identity elements based on historical, cultural, and natural heritage [6].

The island boasts a wealth of culture, in the form of both ancient cultural heritage created or influenced by the above-discussed connections with other civilizations and cultures, and modern-day cultural practices enjoyed by the locals with the participation of foreign visitors. Today, Cyprus is celebrated as the birthplace of the Greek goddess of love and fertility, Aphrodite. Modern-day festivals and public events revolve predominantly around Muslim holidays in the north and Greek Orthodox celebrations in the south. For example, the city of Limassol, the second-most populous on the island, holds a Grand Carnival every year in spring, attended by thousands of locals, and a wine festival to celebrate the harvest in late summer. Overall, the island is in a peaceful state relative to its twentieth century history. The border that divides it has opened up via more and more crossing points since 2003, with nine crossings to date (October 2021), despite ongoing geopolitical disputes with Turkey and other nations.

3. Research Methodologies and Data Collection

The hypothesis leading to this research was that heritage diplomacy has a significant effect on the relations between ethnically diverse groups in Cyprus and can aid in developing sustainable relations and heritage practices. Thus, this study aims to answer a main research question of what the status, importance, and nature of effectiveness of heritage diplomacy are when applied in and for Cyprus. Two underlying questions that guided the research process towards gaining greater clarity of understanding of how the transition from conflicted interaction to greater cooperation in relation to heritage, thus allowing for the creation of TCCH, were:

- (a)

- What were the chronological processes of the diplomatic and political efforts around heritage from Cypriot colonial up to modern times;

- (b)

- What and how TCCH and key actors have done to apply heritage diplomacy as a tool to sustainably tackle such challenges as the Cyprus problem, as well as for what purpose, with what motivations, and future plans.

The research initially commenced with a study of cultural diplomacy and transitioned towards heritage diplomacy, a relatively new theory, which was applied to the case of Cyprus and the TCCH. A case study is an empirical study of human action in a specific and unique setting, which is often social, environmental, and relevant to current events [29]. This type of study requires the collection of data from diverse sources. The case can thus be viewed from different angles for a deeper understanding, in a sense resembling an ethnographic study, in which the research is conducted with the purpose of understanding as opposed to evaluating [30]. Thus, the conclusions drawn from the critical analysis are specific to this case study and may not be applicable in other contexts [31]. However, the study aims to highlight various issues that can be a part of a broader discussion of heritage governance, international and intercommunal relations, conservation, sustainability, etc. The aim is to add to the complexity that Winter argues is needed in the scholarly domain of heritage and global governance [32]. This approach tests heritage diplomacy as a theory and moves away from the generalizing quality of inferences, as this case study will add to a growing number of dissimilar cases in the pool of scholarly work and make use of the extended case methodology [33]. The methodology that guided this research is that of critical social science with a balance between a limited positivist and an interpretive approach. The purpose for this is to test the theory of heritage diplomacy on Cyprus, and build upon it further [34].

The two theories of constructivism and actor–network served as frameworks during the processes of conducting the initial research field examination, building and then carrying out the interviews and observation strategy, analyzing the data gathered, building a discussion, drawing conclusions, and determining further research recommendations. Constructivism posits that action, as opposed to hard and predictable facts, plays a major role in creating and shaping ideas and approaches [35] (pp. 19–22). It is a “social theory of international politics” that emphasizes the social construction of world affairs. This is opposed to the claim of (neo)realists that international politics are shaped by the rational choice of behavior and decisions of egoist actors who pursue their interests by making utilitarian calculations to maximize their benefits and minimize their losses, hence the materiality of international structures [34].

This theory was applied in order to maintain a constant vigilance towards the social construction of diplomatic affairs between the major communities in Cyprus when dealing with heritage via the TCCH. The actor–network theory/approach, which relies on empirical case studies and is a “disparate family of material-semiotic tools, sensibilities and methods of analysis” [36], involves a diverse variety of actors in a complex web of relations that are the effect of this web. The actors could be anything or anyone (humans, organizations, animals, ideas, inanimate objects, geographical formations, etc.) and come into existence as a result of the relations they form with each other, and are thus defined by said relations. The actor–network approach has a descriptive nature, bears a subjective nature via “material semiotics,” and allows for complexity to be promoted. This, as Winter has stated, is important in the field of international heritage and for the theory of heritage diplomacy [23,34]. This theory helps determine the complexity of the relations between actors. Throughout this study, there is a conscious awareness of the theories outlined above in order to determine the most relevant ones in drawing effective conclusions and in building further upon heritage diplomacy as a theory in itself.

Data Collection

Data were collected during a visit to the island in the first half of 2019 via face-to-face interviews and email correspondence; telephone and local WhatsApp conversations were limited to arranging interviews (see Appendix A for sample interview questions). The qualitative nature of the research meant that a method of triangulation was applied during the data collection period [29]. The three main sources of data were official reports and documentation, interviews and observation, and news outlets (including social media). Although triangulation does not guarantee 100% validity, diversity in data sources increases reliability and provides a clearer picture of the case.

The primary sources consulted were written documents in the following categories:

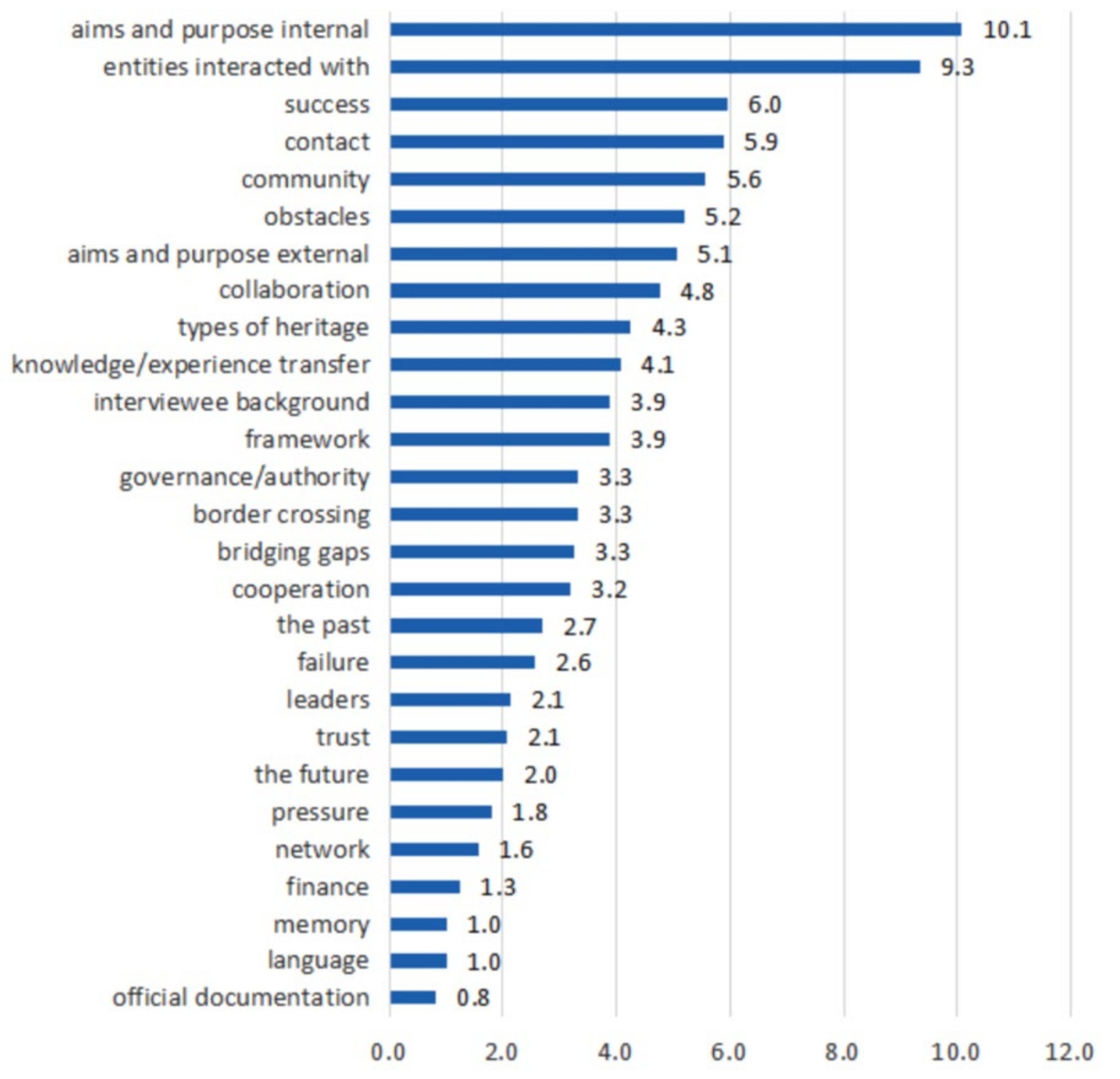

Transcripts of the interviews conducted by the authors and analyzed via the computer application Atlas.ti 8 (Software for Qualitative and Mixed Methods Data Analysis). The transcripts were coded according to main themes, to determine which were most often discussed (Figure 2);

Figure 2.

Popularity percentage bar chart of themes discussed during the interviews. Aims and purposes internal provides a view of how and why TCCH operates; Finance, Framework, Governance/authority, Types of Heritage, and Leaders pertain to discussion of TCCH’s structure. Cooperation, Knowledge/experience transfer, Border crossing, Bridging gaps, Collaboration, and Network pertain to interactions of TCCH with external entities. Aims and purposes external pertains to actions of entities other than TCCH. Success, Trust, Pressure, Obstacles, and Failure pertain to interviewees’ evaluations of the performances and relationships of TCCH and other entities. Language, Memory, Community, The past, and The future add to the discussion of the nature of heritage diplomacy involving TCCH. The remaining themes—Entities interacted with, Interviewee background, Official documentation, and Contact—were noted for practical research purposes.

Transcripts of the interviews conducted by the authors;

Observation notes and impressions;

Background materials and official statements related to the TCCH and other organizations, such as leadership and staff backgrounds, funding sources, mission statements, press releases, etc.;

Official organizational reports and detailed descriptive works on past projects, events, consultancy reports, etc., as well as policy files;

Secondary sources that could act as primary sources, such as mass and social media pieces—newspaper articles, Facebook posts, Instagram posts, YouTube videos, etc.—and original scholarly research and projects based on primary sources.

4. Sustainable Solution and Heritage Diplomacy

4.1. Bridging Gaps in and Transferring Values, Knowledge, and Experience

From an internal perspective presented by the interviewees, a major success of the TCCH is in how the cooperation embodied by the TCCH involves a unique collaboration between the two sides of Cyprus. This is unlike most official interactions that occur between the North and the South, due to the maintained goodwill and acceptance. Simply put, the TCCH shows that Cypriots, regardless of ethnic/religious background, can work together, trust can be created internally, and the country can be unified, if only in the cultural field for now. The TCCH presents itself as an example/idiom for the people of Cyprus and for those dealing with contested areas around the world of how two communities may come together with a level of understanding and respect that may have been missing in the past. They come together to pursue a common target (in this case, preservation of common cultural heritage), with a consolidated spirit of cooperation, and for confidence building, during “periods of deadlock and darkness” or peace. They simultaneously achieve practical results in the heritage protection field for common ends and local, national, and universal benefit. With 33 large projects and about 20 to 25 smaller projects, regular completion ceremonies visited by individuals from both sides, etc., the TCCH has positively applied heritage to building relations between the communities. It has done so with an understanding of what to do and how to work towards the protection of heritage and to overcome nihilism and pessimism in finding solutions to sustainable development. This understanding was reached from the start via a solid mandate base and via the development of flexible formal and informal discussion modes. Weekly meetings, an exponentially increasing pace of monument restoration, increasing expectations, and the expression of interest, appreciation, and satisfaction from the locals on both sides (such as during completion ceremonies, seminar participation, direct requests for preservation, etc.) show that the TCCH’s work is nowhere near slowing down or ceasing. Projects that do not quickly progress are not discarded but kept for a later time. One factor that contributes to this success is the skillful leadership of Takis Hadjidemetriou and Ali Tuncay, who take responsibility for the members during the most difficult and oppositional times. They lead in the maintenance of professional interaction, so internal scientific and technical discussions, however intense, never result in ethnic strife. The ethnic lines that divide Cypriots to this day melt away in the TCCH, where members are more like family than mere coworkers. Another factor is the educational aspect of the TCCH: the locals, especially in the North, can clearly see and understand the nature and purpose of the work, and are thus given the opportunity to increase their own value of heritage sites and buildings. They are given an opportunity to develop trust in the TCCH, adding to the Committee’s success in confidence building amongst the people.

Another success lauded by the interviewees is how productive the cooperation with the EU and the UNDP in the respective funding and implementation of the TCCH’s decisions is. The UNDP presents TCCH as promoting several Sustainable Development Goals, such as goals 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities and 16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions [37]. The participation of the Secretary General (via representation) in the Committee for facilitation and regular measurement of the TCCH’s performance in reports are positive aspects for Cyprus and Cypriot sustainable development and give value to the TCCH’s work. The receipt of funding from the European Commission (EC) is considered a success in itself, contributing greatly to successful TCCH project completion. Initial TCCH success was necessary for the EC to choose to give the Committee funds (currently, approximately two million every two years) for projects it deemed in line with European programs on Cyprus settlement and heritage, four years after the establishment of the TCCH. The EC listens to the TCCH’s ideas for funding and, once provided as part of the EC program, the TCCH successfully “absorbs” the funds.

4.2. Success Where Others Have Failed—Working in the North

The TCCH is successful in an area in which other organizations have failed, thus raising the Committee’s legitimacy as a confidence-building entity in the eyes of international actors and of Presidents Akıncı and Anastasiades. It has filled in the gap created by the UN, UNESCO, the EC, ICOMOS, ICCROM, the World Heritage Fund, the Getty Institute, etc., which are not able to work in the North (as in the case of the need for UNESCO to talk with the RoC representatives from the DoA about Famagusta) or to reach the concerns of the Turkish Cypriot community. The obstacle of nonrecognition of the North by the international arena is overcome by the TCCH with the executive aid of the UNDP. From an external perspective, the TCCH receives interest from the international community, as they are viewed to be successful. The European community has honored Hadjidemetriou and Tuncay for their work; the EU assigned them the title of European Citizen. The TCCH has further exhibited its work in Brussels. A more local success for the TCCH is the continual approval of the leaders, ministers, negotiators, and departments (such as the DoA, despite the occasional expression of negative attitudes) with whom the TCCH maintains contact for increased legitimacy of the importance of their work for reconciliation, improved understanding, and help in confidence building; the TCCH’s legitimacy is further supported by the expertise and former bicommunal experience of its members who strive towards politically neutral work, without the political sensationalist confrontation that once permeated heritage-related interactions. Thus, the TCCH’s work is not viewed as illegal, as efforts that involve the North often are. This is in part attributable to the experience many of the key individuals involved in the TCCH have had with the NMP, where the most successful collaborations were between architects and engineers with clear practical goals and not political agendas. What has also helped the TCCH is that the physical border on the island is gradually becoming less strict and meaningful.

All in all, the TCCH’s success embodies a gradual change of attitude towards a contested topic—cultural heritage—making it one that is no longer an arena for confrontation, politicization, and conflict, but one where trust is created and maintained with reciprocity in the protection of each other’s heritage, increasingly by and between more and more various entities involved and cooperating: members, advisors, leaders, authorities, the Cypriot public, International Organizations (IOs), etc. The TCCH is both the result of and a vehicle for this change. It acts as an influencer of values of cooperation, aiming to extend the knowledge of its importance and to increase Cypriots’ capacity for it. The TCCH can thus act as an example for communities and politicians in other nations who may wish to make use of the “gluing effect” of heritage when building diplomatic relations and starting collaboration between parties with differing political opinions.

The TCCH succeeded where other committees have failed: appointed individuals not tied by obligations to structures, ministries, or government departments. These latter three entities are willing to undertake time-consuming communication via a “company line,” memo writing, continual re-explanations of the same issues, and other division-related departmental agendas and constraints. Alongside the Lost People, Education, and the Cultural Committees, the TCCH is one of the most active and productive Committees.

Heritage and its preservation are a sensitive topic that can be difficult to apply in a volatile field such as politics. The TCCH or the cultural heritage field alone would not be able to provide a solution to sustainable development, but it is a valid example of the type of platform that could be established to successfully promote confidence building between two sides in spheres that can be shared, on a local or national level and internationally. There are, however, several aspects presented by the interviewees as obstacles, pressure, and downright failures in the fields of cooperation and collaboration as experienced prior to the establishment of and by the TCCH.

4.3. Inflexible Memory, Dangerous Zones, and Legal Constraints

A major continuous failure in interactions prior to the establishment of the TCCH were the accusations between Greek and Turkish Cypriots that would stall practical results in connection with work on monuments. This involved a limited understanding of current issues because of focus on previous events such as the invasion. The TCCH continually focuses on understanding and cooperation in the cultural field, which, when politicized, could easily become a ground for confrontation. Yet, it can promote such values only to a limited extent, as memory of the invasion and legal constraints on the north side continue to prevail and affect the direction that relations between communities on the island take. Although the TCCH allows for opportunities for the people to visit their heritage on the other side, there is limited opportunity for regular consistent visits, for example, for attending mass and services in churches in the North and prayer in mosques in the South.

According to several interviewees, community-related issues are a very sensitive topic amongst Greek and Turkish Cypriots, including on the legal level. While ideological and physical borders may have been overcome within the TCCH, the Committee has not succeeded in reaching out to the people of the island in its entirety. Obsession with attempts to find any excuse to highlight the illegality of the other’s presence (as in the case of village name changes), show that the two sides are still against each other in areas that are not always heritage-related and somehow have to be addressed differently. The TCCH is powerless to intervene and must follow the rules. With the presence of the Turkish military in the North, political borders are difficult if often impossible to overcome, as are borders built in the minds of the people over decades of living in a divided country. This is despite their possible participation in or acceptance of the TCCH activities. There have been reports of cases of vandalism, not unusual in the work of the TCCH.

The TCCH initially failed to reach out to communities for project participation due to lack of time, leaving such interactions purely for completion ceremonies. Gradually and with initial limited participation, the TCCH began to conduct seminars and workshops to attract and educate the public. Nonetheless, there is a failure on the part of the TCCH to provide a complete experience for the public for whom the heritage preservation is purportedly being carried out and to “interpret” the work to other communities. There is, according to an interviewee, a gap in knowledge of the nature and value of cultural heritage for the people in the North. Churches in Famagusta that could be open for public visits are standing idle when not in rare use for ceremonies. There seems to be a lack of opportunity for individuals from other communities to visit the heritage of the other, and thus to appreciate, admire, and value it.

The TCCH cannot move forward beyond its current local efforts due to the nonrecognition of the North by the international arena. Only the RoC can interact with the EC or with UNESCO, whereas it cannot officially work with/talk to the TRNC. The TCCH does not even have an official office, as that would mean having to choose a side, making it difficult for applications for specific site preservation to reach the Committee; this lack of physical space, as well as not being legally defined on either side of the island division (as in, it is just a group of volunteers), add to the somewhat virtual characteristic of the TCCH, making it less tangible and official than it would otherwise be. The TCCH also has no official power to directly communicate as an official body with entities such as nations outside of Cyprus, i.e., only individuals from the Committee can communicate when they visit other countries. As noted above, possible international diplomatic communication is conducted by the EC, which represents several countries—not an ideal situation, according to one interviewee. Furthermore, the TCCH cannot raise funds bilaterally, only through the EC or via spontaneous donation, making the TCCH dependent on other organizations for taking direct funding initiative.

The TCCH has yet to expand its reach and scope. The Committee overall does not seem to want to pursue contact with specialists apart from architects or conservators located locally. This means that it misses out on the chance to partake in international expertise and learn new technologies not yet available locally, as well as to gain firsthand experience in unique heritage-related interactions outside of Cyprus, ones that may teach the TCCH further transferable skills in sustainable development. However, several interviewees mentioned the TCCH presidents sharing the TCCH experience at conferences and talks outside of Cyprus, such as in Brussels, where TCCH has a chance to address the EU, and, with some uncertainty, Dubrovnik, where heritage has also acted as a tool for promotion and maintenance of conflict, as well as in post-war recovery efforts; how transferable TCCH methods are to other groups and areas around the world is beyond the scope of this research. [38] Several members actively conduct heritage and sustainability research beyond the scope of the work of TCCH and beyond Cyprus, providing potential but as yet unexploited channels of cooperation on sustainable development of heritage practices [39,40,41]. Finally, the TCCH has yet to address the possibility of preserving sites that require immediate attention due to being demolished as a result of not being listed or legally approved as heritage sites, such as valuable 20th century modern buildings and industrial heritage.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The Cyprus Problem has stagnated on the geopolitical plane, where attempted solutions have been focused. From UN mediated attempts at unification via the Annan Plan to most recent talks between Anastasiades and Akinci in 2017, efforts fall through with the same result, in which one of the parties is unsatisfied with an element or two in the unification deal proposed by the other party. The TCCH does not deal with unification in such a direct manner. The TCCH works with what is already indelibly shared by and has not been divided as directly as the communities. Cultural heritage and monuments of Greek Orthodox, Latin, Muslim, Ottoman, Venetian, etc., origins are dispersed throughout the island and, due to a mélange-like nature, have made for suitable grounds to mingle the communities via common pursuit of heritage preservation and appreciation.

Immovable cultural heritage is shared by the parties who are building diplomatic relations between themselves. However, heritage diplomacy lies within the international arena, with heritage governance being partaken in by nations, IOs, NGOs, nonstate actors, private companies on behalf of states, etc., across national borders. The case of heritage diplomacy in Cyprus involves interactions across a border that divides the island into a recognized state, the RoC, and a non-recognized self-proclaimed state, the TRNC, a border that many locals still hope is temporary. Although the TRNC is unrecognized by the legal and international domains, this state considers itself to be independent and does not recognize the RoC; the RoC, in turn, does not recognize the TRNC. However, the TCCH represents neither the RoC nor the TRNC and instead represents the interest of the people and works for the people. Our research showed that several TCCH members have the idea of a federal Cyprus in the future, but in the meantime, the TCCH works on promoting unity amongst the public and building confidence in a peaceful and prosperous future for the island as a whole and for all communities. Cultural heritage will be unable to enhance sustainable development on its own for the island in its entirety and in the social, economic, and political spheres. This makes the TCCH’s efforts only part of what must be implemented to reach a solution, in this case, the part that involves influence over attitudes to overcome nihilism/pessimism, while working on a valuable part of society’s interests, its immovable cultural heritage. The TCCH will not be able to influence extensive blockages in the relations between the RoC and the TRNC, including something as simple as the two governments directly talking to each other. However, it succeeds in bypassing the issues of nonrecognition of the North for practical achievements and building public and community relations. This is despite its virtual state, due to not having an official office, even in areas such as the Buffer Zone, or at the Home For Cooperation, which is a stumbling block in the efficiency of its work.

The TCCH has demonstrated significant success in community relations as a result of mutual support in the heritage field, amongst Greek, Turkish, and Maronite Cypriots, as demonstrated by the ceremonies’ popularity and attendance. TCCH acted as facilitator of communication and interaction between locals from around the island and from varying ethnic backgrounds, who cordially mingle at these events. TCCH has done this alongside its strictly professional collaboration for the purposes of heritage preservation and maintenance. The members are convinced of the benefit to and support of the public, yet there is still much space for improvement in communication with and the project involvement of the public, especially in the North. The relations are mostly bicommunal, with limited tricommunal and multicommunal efforts. Maronite Cypriots may not have had much of a say in the larger domestic and international affairs and discourse due to the spheres being overwhelmed by Greek and Turkish Cypriot mutual issues, yet syncretism is a factor that the TCCH has attempted to bypass via inclusion of Maronite heritage projects. Over time, distinction along such ethnic and religious lines would ideally gradually cease to be a part of relations and relations would be natural enough for community heritage diplomacy to no longer be needed. The parties would become one community where individuals of various cultural, ethnic, and religious backgrounds coexist and thrive in their diversity of cultural and heritage elements, which they would mutually respect, manage, and preserve. This may even extend to immigrant communities, though whether this is possible for Cyprus is yet to be seen.

The TCCH’s diplomatic approach has achieved technical success, which was the primary reason for the establishment of the Committee and of the Advisory Board. This study has in part validated the effectiveness of the object-oriented approach, i.e., building relations via technical work with a physical medium [42]. It has clearly shown that the TCCH focuses mainly on social impact, but has not studied whether this is detrimental to making the preservation efforts more efficient. Cooperation purely for technical preservation is no longer the sole purpose of the TCCH, as its philosophy over the years has evolved to make cooperation more sustainable in the long run. The development of a language of cooperation, moving away from language of conflict and blame, as well as maintenance of respect for emotional and memory factors, are key to the success of the diplomatic efforts of the TCCH towards the public. Interviewees have, however, stated concern over financial and human resource limitations and have expressed desire for greater participation of experts, perhaps from abroad.

The heritage diplomacy that is involved in the processes of the TCCH may be termed differently from “community” heritage diplomacy. As the TCCH ultimately has no full independence and always answers to the presidents of the RoC and the TRNC, this may make the TCCH an entity that carries out whatever the highest authority approves of. The TCCH may be viewed as indirectly working as a diplomatic convoy between the higher authorities and the public. The presidents’ support is important to the reputation and validity of the TCCH’s work but has not been enough to garner the full support of government departments and the DoA. A key factor in the TCCH’s work is relational success with ministries and key political figures, both a propellant of the Committee’s efforts and a result of the legitimacy of the TCCH’s work, though attempts at sabotage by figures who disagree have been known. The TCCH’s diplomacy cannot penetrate deeply ingrained attitudes as well as the members would like, meaning that confidence building may not be enough to ensure that the ideological and emotional climate on the island fully transforms into one that will ensure peaceful reunification. Nonetheless, it is possible that the TCCH partakes in exerting soft power on behalf of the state via its peace and confidence building along the path of heritage conservation. It thus employs public heritage diplomacy. Furthermore, although heritage politicization was stated by interviewees to no longer be a factor in the TCCH efforts, Greek Cypriots purportedly being forced to fund the Apostolos Andreas monastery conservation and preservation project due to the nature of Turkish Cypriot funding begs the question of whether the power exerted on and via the TCCH is other than soft power [5]. Financial intrigue may even mean the Committee is present in the realm of hard power. However, a deep look into the nature of these interactions was beyond the scope of this study.

An alternative approach to the elements behind both community and public heritage diplomacy may be civil heritage diplomacy. Taking into consideration the fact that TCCH members are volunteers who do not hold political positions, they can be seen as civilians who partake in diplomatic pursuits with the intention of locally influencing the social atmosphere of the Cyprus Problem, something that is usually performed by politicians and officials on local and national levels on both sides [43]. Individuals who participate in TCCH projects and are not members of the TCCH, i.e., members of the public, whether Greek/Turkish/Armenian/Maronite/etc., Cypriot, also partake in and employ community heritage diplomacy. However, to have sociopolitical influence does not seem to be the intention of these individuals, as determined from the interviews; the public is interested in preserving their ancestral memory. The public’s intention requires further inquiry for a clearer view.

Heritage in diplomacy plays a role in the TCCH activities that involve the EC, the UNDP, and other nations who do not share in Cyprus’ heritage but may wish to learn from the Committee’s successes. The study did not determine the participation of IOs beyond financial support by the EC and technical and mandating support by the UNDP, in line with existing projects for both organizations. Furthermore, the EU has officially honored the TCCH leaders, Ali Tuncay and Takis Hadjidemetriou, for their efforts. If these entities did not approve of the direction of the Committee’s work, it would have been highly detrimental to the success of the projects, and the TCCH would not have been able to carry out its diplomatic pursuits. The TCCH’s work thus falls well in line with the heritage governance pursuits of the EU and the UN, which in this case involve peaceful cooperation for heritage conservation, preservation, and management. To what extent the participation of these entities means the acceptance of the TRNC is yet to be determined, but the fact that the TCCH works with communities and not governments means that TRNC nonrecognition is an ongoing factor, and the IOs’ support is purely for the benefit of the people, though further research into the IOs’ intentions is recommended.

Areas with similar conflict and entities from other areas of interest that require the building of relations and confidence under strained circumstances may benefit from using the example of the type of technical platform that the TCCH employs for and via its diplomatic pursuits. This study has highlighted the Committee’s enthusiasm in sharing the knowledge behind its success in establishing positive connection and sustaining collaboration internally and with both communities [44]. The successes and failures of the TCCH allow for the determined types of diplomacy to possibly be successfully applied in areas and platforms with similar conflict and politicization issues for the building of relations and confidence under ideologically strained circumstances. Several members have expressed their positive views on the TCCH’s future and on sustaining an expansion of heritage management and diplomatic efforts. Whether the diplomatic efforts of the TCCH will, in fact, sustain their success in the future and grow in scope will be seen over time and will, potentially, provide for further research and insight into the interrelation of sustainable development and heritage diplomacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.G. and Q.W.; methodology, O.G.; software, O.G.; validation, O.G. and Q.W.; formal analysis, O.G.; investigation, O.G.; resources, O.G.; data curation, O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.G.; writing—review and editing, Q.W.; visualization, O.G.; supervision, Q.W.; project administration, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Liberal Arts, Shanghai University (protocol code 128; date of approval: 26 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Sample Questions for the Semi-Structured Interviews

- What does TCCH do and what is the core mission or vision guiding it?

- What might be the biggest influences your work and the work TCCH does in general have and on whom, on what?

- How is governance handled?

- How has cooperation been established and maintained? With whom and along what kind of channels? What kinds of borders would you say are crossed?

- What might be some obstacles to such cooperation that you have encountered?

- Are there instances where collaborations have happened over heritage that is not shared between the communities?

- Has there been any heritage-based international cooperation with nations/organizations/communities/etc. who have historical connection with the heritage that TCCH focuses on, i.e., the heritage is common/shared?

- Has there been any heritage-based cooperation with nations/organizations/communities/etc. who do not have historical connection with the heritage that TCCH focuses on at all? Internationally and domestically?

- Have there been any examples of when TCCH worked on sites that were previously not viewed as heritage but eventually had their status changed to one of important cultural/natural heritage?

- Does TCCH do any heritage-based work beyond Cyprus? If yes, why?

- Does TCCH itself in any way build non-heritage-based diplomatic relations, and if yes, why and what are some examples?

- Can you think of any other examples of heritage playing a role in diplomatic relations within Cyprus, perhaps between Cyprus and other nations/organizations/communities/actors? Recent or in the history of the island?

- And finally, do you have any thoughts on what the future of TCCH may look like? Further developments and plans? Perhaps contributions to international and global heritage governance?

References

- Mallinson, W. Cyprus: Diplomatic History and the Clash of Theory in International Relations; I.B.Tauris: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, W. Cyprus: A Modern History; I.B.Tauris: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, S. Threats to Cultural Heritage in the Cyprus Conflict. In Heritage Crime: Progress, Prospects and Prevention; Grove, L., Thomas, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, M.E. War and Cultural Heritage: Cyprus after the 1974 Invasion; Minnesota Mediterranean and East European Monographs: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjisavvas, S. Perishing Heritage: The Case of the Occupied Part of Cyprus. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2015, 3, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.M.; Hatay, M. Cyprus, ethnic conflict and conflicted heritage. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2010, 33, 1600–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaphiriou, L.; Nicolaides, C.; Miltiadou, M.; Mammidou, M.; Coufouda, V. The Loss of a Civilization: Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Occupied Cyprus; Press and Information Office of the Republic of Cyprus: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2012. Available online: http://www.mfa.gov.cy/mfa/embassies/embassy_stockholm.nsf/A64B1EE900605967C22578B90025C290/$file/Destruction%20of%20cultural%20heritage%20(English%20version).pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Knapp, A.B.; Antoniadou, S. Archaeology, politics and the cultural heritage of Cyprus. In Archaeology Under Fire Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East; Meskell, L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gramer, R.; Surana., K. Cracking the Cyprus Code. Foreign Policy. 14 March 2017. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/14/cracking-the-cyprus-code-can-a-cypriot-reunification-deal-go-through-diplomacy-united-nations-turkey-greece-frozen-conflict/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Peristianis, N.; Mavris, J.C. The ‘Green Line’ of Cyprus: A Contested Boundary in Flux. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2012; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News: Cyprus Opens First New Border Crossings in Years. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-46182370 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- BBC News: Emotion as Cyprus Border Opens. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/2969089.stm (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Demetriou, O.; Ilican, M.E. A peace of bricks and mortar: Thinking ceasefire landscapes with Gramsci. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewers, M.C. The Nicosia Master Plan: Historic Preservation as Urban Regeneration. Master’s Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, M.J.K. (Ed.) The Armenian Church of Famagusta and the Complexity of Cypriot Heritage: Prayers Long Silent; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Davoodi, T.; Dağlı, U.U. Exploring the Determinants of Residential Satisfaction in Historic Urban Quarters: Towards Sustainability of the Walled City Famagusta, North Cyprus. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Open Street Map. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/export#map=9/35.1267/33.4616 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Hampton, M. Heritage, local communities and economic development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijkamp, P.; Riganti, P. Assessing cultural heritage benefits for urban sustainable development. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2008, 10, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roders, A.P.; Oers, R.V. Editorial: Bridging cultural heritage and sustainable development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. INSULA–Int. J. Isl. Aff. 2007, 16, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. Heritage diplomacy. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Lee, H. Difficult heritage diplomacy? Re-articulating places of pain and shame as world heritage in northeast Asia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, R. Transitions in the Ottoman Waqf’s traditional building upkeep and maintenance system in Cyprus during the British colonial era (1878–1960) and the emergence of selective architectural conservation practices. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brey, H.; Heinritz, G. Ethnicity and Demographic Changes in Cyprus: In the “Statistical Fog”. Geogr. Slov. 1992, 24, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices, 2nd ed.; Ebook; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Loizides, N.G. Ethnic Nationalism and Adaptation in Cyprus. Int. Stud. Perspect. 2007, 8, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Eurepos, J.G.; Wiebe, E. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Shozende Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mosse, D. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice; Pluto Press: London, UK; Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D.; Marvasti, A. Doing Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Shozende Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. Heritage studies and the privilege of theory. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela, L.; Roccu, R. Case study research and critical IR: The case for the extended case methodology. Int. Relat. 2019, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Behraves, M. “Constructivism: An Introduction.” E-International Relations. 3 February 2011. Available online: https://www.e-ir.info/2011/02/03/constructivism-an-introduction/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Onuf, N.G. World of Our Making; University of South California Press: Columbia, SC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Law, J. Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics. Heterogeneities. 25 April 2007. Available online: http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law2007ANTandMaterialSemiotics.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- UNDP: Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage Completes Conservation Works and Begins Tender Process for Several New Sites across the Island. Available online: https://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/20201/technical-committee-on-cultural-heritage-completes-conservation-.html (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Schneider, P. (Ed.) Catastrophe and Challenge: Cultural Heritage in Post-Conflict Recovery. In Proceedings Fourth International Conference on Heritage Conservation and Site Management, Cottbus–Senftenberg, Germany, 5–7 December 2016; Btu Cottbus: Cottbus, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides, G. Urbanisation and Town Management in the Mediterranean Countries Sub-regional study: Malta and Cyprus. In Mediterranean Meeting on «Urban Management and Sustainable Development, Barcelona, Spain, 3–5 September 2001; Mediterranean Commission on Sustainable Development: Barcelona, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides, G. The Economics of Urban Morphology Methodologies and Tools for Analysis in Urban Morphology. Cyprus Network for Urban Morphology, Proceedings of the1st Regional Conference, Buffer Zone, Nicosia, Cyprus, 16–18 May 2018. pp. 2–16. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Acalya-Alpan/publication/346659724_Making_Past_Morphological_Traces_Legible_through_Design_Intervention/links/5fcd332992851c00f8588e30/Making-Past-Morphological-Traces-Legible-through-Design-Intervention.pdf#page=14 (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Kara, C.; Doratlı, N. Predict and Simulate Sustainable Urban Growth by Using GIS and MCE Based CA. Case of Famagusta in Northern Cyprus. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grchev, K.; Dincyurek, O. The Challenges of the “Divided” Heritage of Cyprus. In Cultural Landscape in Practice; Amoruso, G., Salerno, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jarraud, N.; Louise, C.; Filippou, G. The Cypriot Civil Society movement: A legitimate player in the peace process? J. Peacebuilding Dev. 2013, 8, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapp, L. Define ‘Mutual’: Heritage Diplomacy in the Postcolonial Netherlands. Future Anterior 2016, 13, 66–81. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).