WeThe15, Leveraging Sport to Advance Disability Rights and Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Study Context and Objectives

- Describe the normative backdrop to WeThe15 and the campaign drivers and purpose.

- Analyze media coverage of the 2016 Summer Paralympics as a proxy to popular culture or public perception of disability.

- Examine the potential of para-sport and para-athletes to identify and overcome barriers to disability inclusion and promote disability rights.

- Identify how WeThe15 can intentionally leverage sport to advance the rights of people with disabilities in line with sustainable development objectives.

1.2. Materials and Methods

1.2.1. Hypothesis and Research Questions

- Are the current international normative frameworks across sport, human rights, and sustainable development a good foundation for disability inclusion?

- Do para-athletes identify as advocates for disability inclusion?

- Does the media report on disability in a manner that advances or stifles understanding and attitudes around disability?

- Can sport impact disability rights and sustainable development objectives?

1.2.2. WeThe15 Descriptive Research and Literature Review

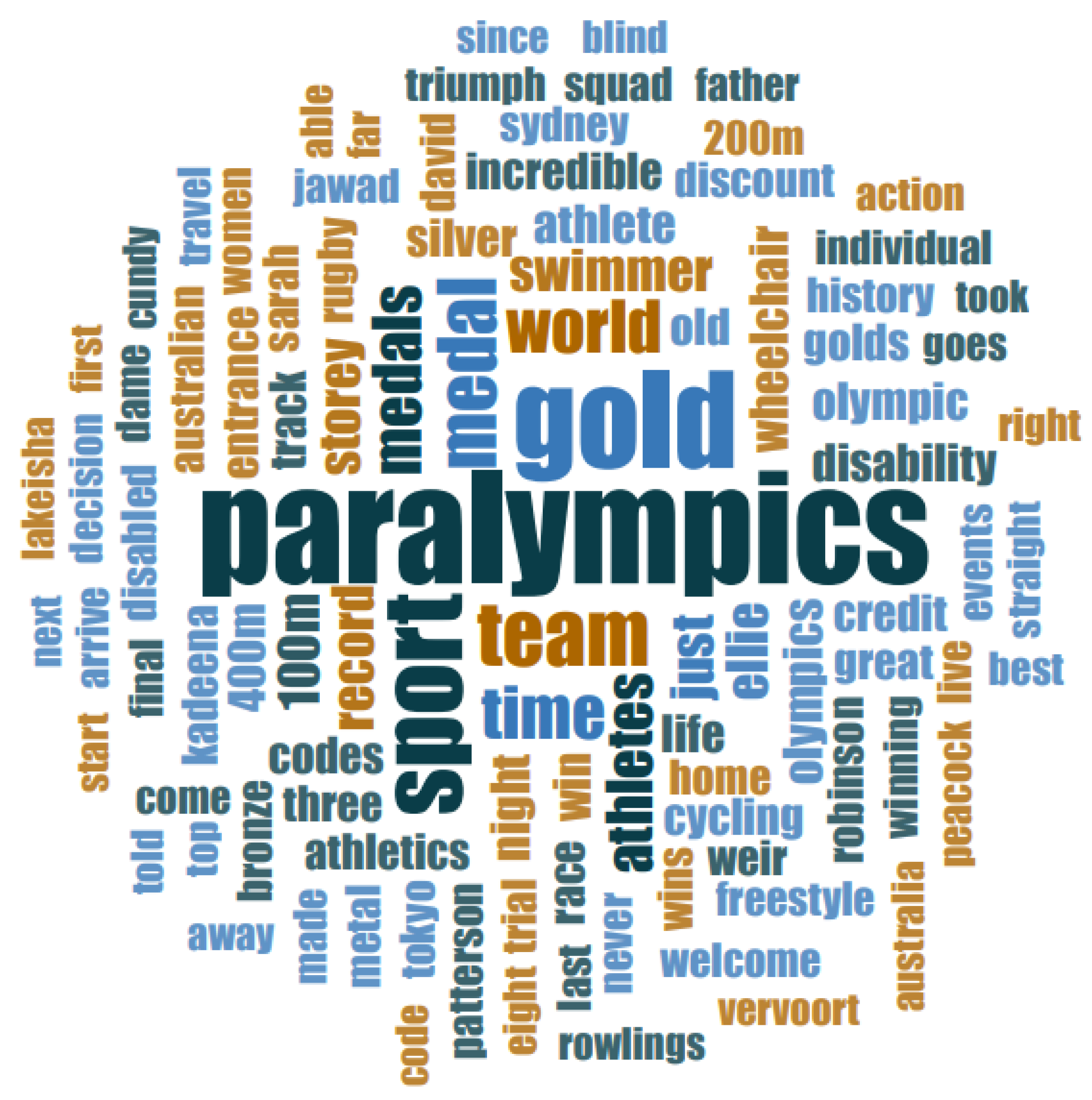

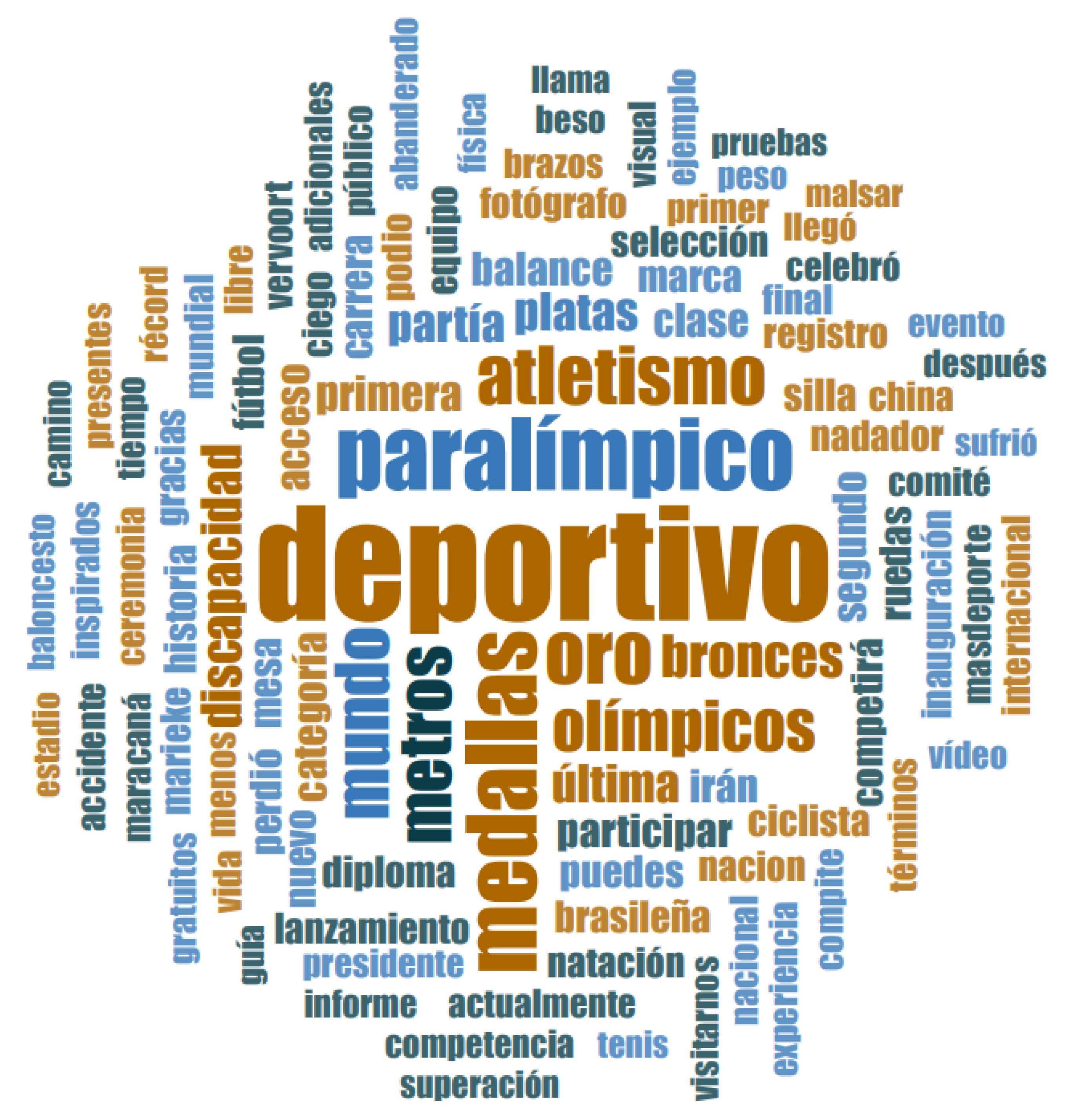

1.2.3. Empirical Research across Media and Athletes

- (a)

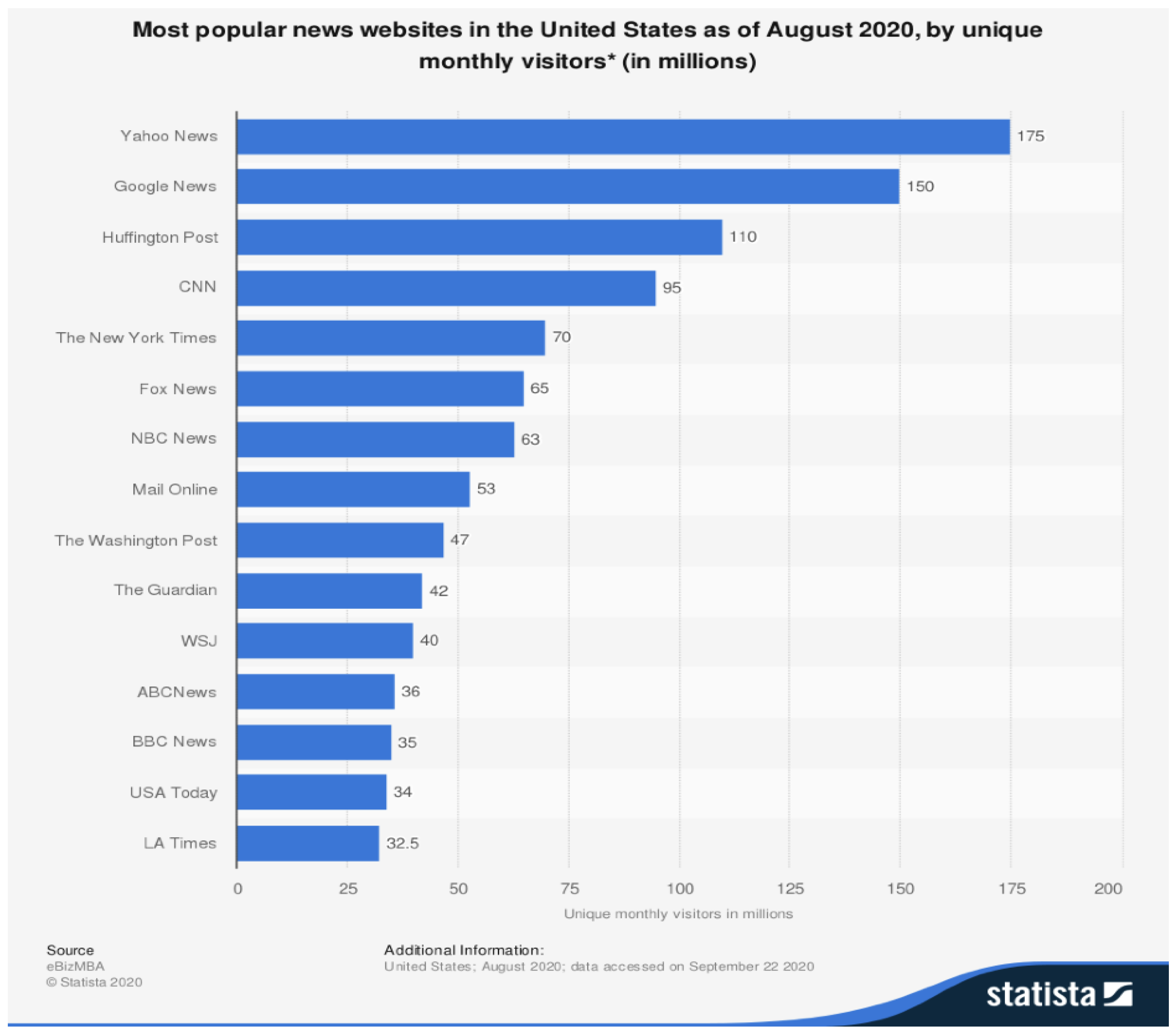

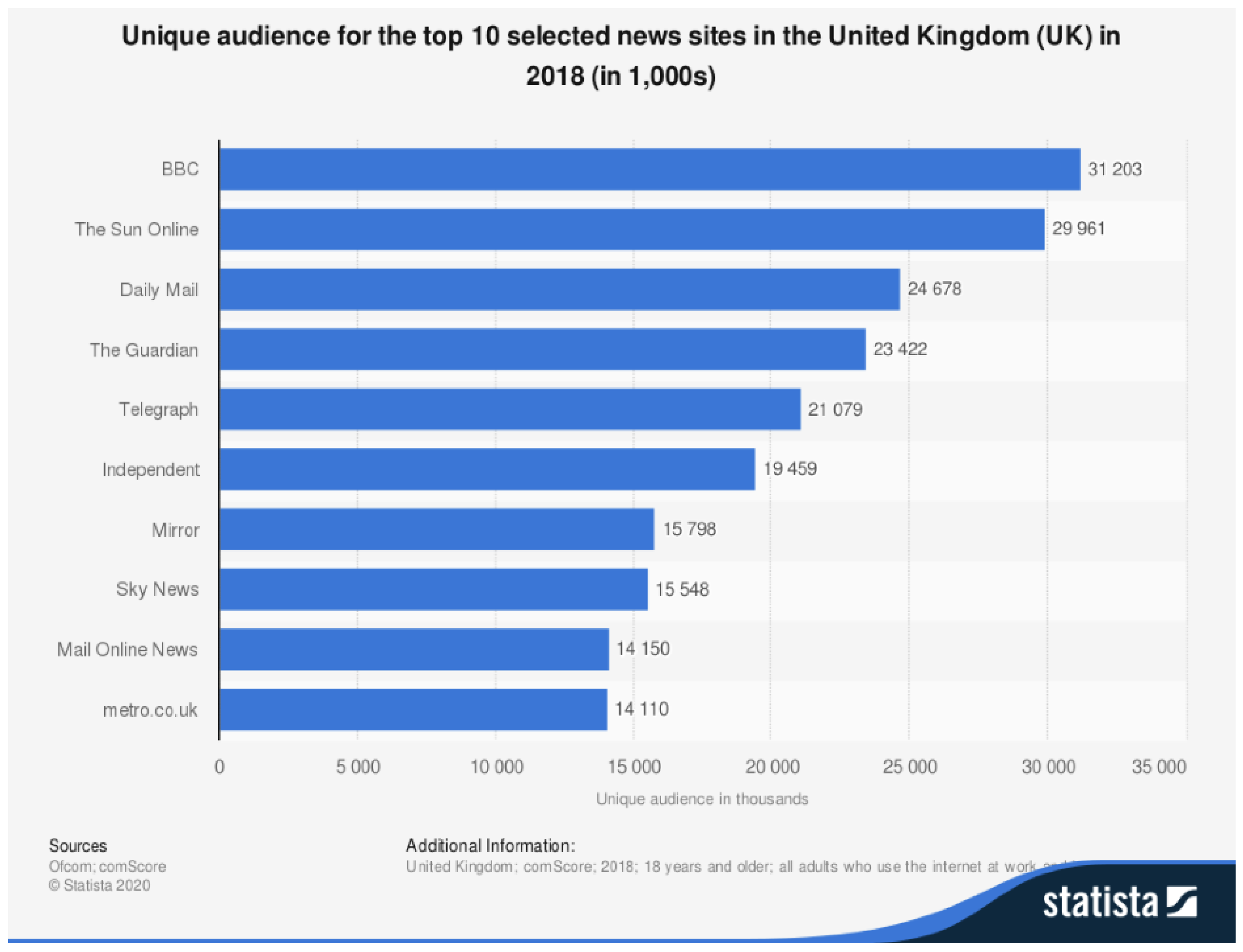

- Mainstream Media Sampling

- Were published between 6 August 2016 and 18 October 2016;

- Covered the 2016 Summer Paralympics.

Analysis

- (b)

- The Athlete’s Platform Role: The Athlete Listening Experiment

Focus Groups

Limitations

2. WeThe15 Descriptive Research and Literature Review

2.1. WeThe15

2.2. Disability, Disability Rights Sustainable Development, and Sport

Sport is also an important enabler of sustainable development. We recognize the growing contribution of sport to the realization of development and peace in its promotion of tolerance and respect and the contributions it makes to the empowerment of women and of young people, individuals and communities as well as to health, education and social inclusion objectives.[7] (p. 13)

3. The Role and Impact of Sports on Human Rights and Disability Rights

3.1. Impact of Sports on Individuals with Disabilities

3.2. Health and Well-Being

3.3. Income and Employment

3.4. Full Development of Human Potential and Empowerment

3.5. Impact of Sports for Persons with Disabilities on Societies

“Guadalajara…gain{ed} awareness on what inclusion and accessibility really means. Before we didn’t have accessible stadiums…ramps…inclusive traffic lights…commerce interested in including clients with disabilities…sign language…now we do. This is all because we had programs and public policy to promote these changes…we created the municipal secretariat for inclusion of people with disabilities we…work with civil society to make sure Guadalajara is inclusive for all.”

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; …Such are the places where every man, woman and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerned citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.[50]

4. Results

4.1. Media Listening Experiment Results

“Ibrahim Hamadtou, the table-tennis player that touched the world (…) through his story he inspires the world to overcome lives’ obstacles.”(RPP, 2016)

“For (kids) to see, ‘They’re in wheelchairs and they can do this. Or, they don’t have a leg and they do this, then I guess I can, too,’”(NBC, 2016)

4.2. Athlete Listening Results

“I don’t influence anything purposely, I just do my thing, live my life looking for my own objectives; there will always be other people trying to imitate us, use us as an image, as inspiration. But I don’t believe that because I feel as equal as anyone else. We all have difficulties, we all have limitations, we all have problems.”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Greeting and Presentation of Participants 5 min | Presentation and acknowledgement of attendance to the participants. Likewise, the moderator will emphasize on:

|

| General Approach to Sport 15 min | Objective: Identify what they like the most and if sport is one of these topics.

What does that experience convey to you? Moderator: at this point it is important for the moderator to inquire if sport is a primary activity of interest. Use the inverted pyramid technique (from general to specific) to focus on sports.

|

| The role of Sports 15 min | Objective: To clarify the role of sport in the lives of the participants.

Why did they choose it? What do you like about it?

|

| Obstacles and Support Networks in Sport 25 min | Objective: To inquire about the obstacles that participants have encountered in their relationship with sports.

How have you dealt with these kinds of situations? What should be done to avoid them?

Who has supported you? Why do you remember them? |

| My Personal History and Sport 35 min | Objective: Recognize how sports plays a role in personal transformation in the participants. Exercises # 1 Jam Board “Sports and I” The participants must write a paragraph-long short story whose main theme is “Sport in my life.” Then, two stories will be shared to encourage dialogue between the participants.

Encouragement topics: if the general questions do not produce answers, try with self-confidence, opportunities, the development of skills in other fields, the change in attitudes of other people towards the participant. Do you feel that sport has changed your perception of yourself? Do you feel that the perception others have of you has changed? Oral survey: as closure and summary Their participation is appreciated, it is said that it was very productive, and they are asked to think for 1 min, as a way to conclude, the answers to the following questions: How has sport changed your lives? Why are sports important for people with physical disabilities? |

Appendix C

References

- International Paralympic Committee. #WeThe15—A Movement for an Inclusive World. Available online: https://www.wethe15.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- International Paralympic Committee. WeThe15: A Global Movement to Transform the Lives of the World’s One Billion Persons with Disabilities Over the Next Decade. Side Events—UNDESA Division for Inclusive Social Development. Available online: https://teamup.com/ksmv4e1gd1ruzbzoso (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games—Opening and Closing Ceremonies. Available online: https://olympics.com/tokyo-2020/en/paralympics/ceremonies/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III), 1948, UN Doc. A/810 at 71. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- OHCHR. Report on Physical Activity and Sports under Article 30 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2021. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Disability/Pages/Physical-activity-sports.aspx (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 13 Dec 2006; United Nations: New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- UNESCO. Report of the Sixth International Conference of Ministers and Senior Officials Responsible for Physical Education and Sport (MINEPS VI). Annex 1 Kazan Action Plan. SHS/2017/PI/H/14 REV. Paris. September 2017. Adopted on 14–15 July 2017. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252725 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly. Strengthening the Global Framework for Leveraging Sport for Development and Peace, 2018, 14 August 2018, A/73/325. Available online: http://undocs.org/A/73/325 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly. Sport for Development and Peace Sport: A Global Accelerator of Peace and Sustainable Development for All. Report of the Secretary-General A/75/155. 2020. Available online: http://undocs.org/A/75/155 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Godsil, R.D.; MacFarlane, J.; Sheppard, B. Volume 3: Pop Culture, Perceptions, and Social Change—A Research Review. 2016. Available online: https://perception.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/PopJustice-Volume-3_Research-Review.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Boyle, R.; Haynes, R. Power Play: Sport, the Media and Popular Culture, 2nd ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburg, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.M. The ‘Revolt of the Black Athlete’: Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s 1968 Black Power Salute Reconsidered. In Myths and Milestones in the History of Sport, 1st ed.; Wagg, S., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, I. Democratizing journalism? Realizing the citizen’s agenda for local news media. J. Stud. 2010, 11, 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- International Paralympic Committee. Strategic Plan 2019–2022, 2019. Bonn, Germany. Available online: https://www.paralympic.org/sites/default/files/document/190704145051100_2019_07+IPC+Strategic+Plan_web.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Legg, D. Development of the IPC and Relations with the IOC and Other Stakeholders. In The Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies; Brittain, I., Beacom, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 15–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, P.; Ziegler, S.; Zurmühl, U. Support to Organisations Representative of Persons with Disabilities; Handicap International: Lyon, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Retief, M.; Letšosa, R. Models of disability: A brief overview. HTS Teol. Stud. Theol. Stud. 2018, 74, a4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herwig, O. Universal Design Means Design for everyone. In Universal Design: Solutions for a Barrier-free Living; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, United Nations, Treaty Series. 18 December 1979, Volume 1249, p. 13. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cedaw.aspx (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly Convention on the Rights of the Child, United Nations, Treaty Series. 20 November 1989, Volume 1577, p. 3. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, United Nations, Treaty Series. 16 December 1966, Volume 993, p. 3. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Carty, C.; Carney, S.; Tralee, Kerry, Ireland. UNESCO Chair MTU., Sport & Human Rights Reporting, UN & Regional Instruments. [email protected]. Personal communication, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yelamos, G.M.; Carty, C.; MacLachlan, M. Assessing and improving the national reporting on human rights in and through physical education, physical activity and sport (PEPAS). Rev. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2020, 29, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. MINEPS VI. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of Ministers and Senior Officials Responsible for Physical Education and Sport. Korston Hote, Kazan, Russia, 13–16 July 2017; Available online: https://en.unesco.org/events/mineps-vi-sixth-international-conference-ministers-and-senior-officials-responsible-physical (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Carty, C.; Tralee, Kerry, Ireland. Working Paper to the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. [email protected]. Personal communication, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Carty, C.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Bull, F.; Willumsen, J.; Lee, L.; Kamenov, K.; Milton, K. The first global physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines for people living with disability. J. Phys. Act Health 2021, 18, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. RECOVERING BETTER: SPORT FOR DEVELOPMENT AND PEACE Reopening, Recovery and Resilience Post-COVID-1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/12/Final-SDP-recovering-better.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Blauwet, C.; Willick, S.E. The Paralympic Movement: Using sports to promote health, disability rights, and social integration for athletes with disabilities. PM&R 2012, 4, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.M.; Thompson, A.M.; Blair, S.N.; Sallis, J.F.; Powell, K.E.; Bull, F.C.; Bauman, A.E. Sport and exercise as contributors to the health of nations. Lancet 2012, 380, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaitz, E.S.; Miller, M. Chapter 5: Adaptive Sports and Recreation. In Pediatric Rehabilitation: Principles & Practice; Demos Medical Publishing, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.C.; Khoo, S. Benefits and barriers to sports participation for athletes with disabilities: The case of Malaysia. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 1132–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Paralympics and IPC. Paralympians to earn equal payouts as Olympians in the USA. Available online: https://www.paralympic.org/news/paralympians-earn-equal-payouts-olympians-usa (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Hungary Today. One-off Prize Money Increased for Paralympians. Available online: https://hungarytoday.hu/one-off-prize-money-increase-sports-olympics-paralympians/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Marca. Un Paso Más Hacia La Igualdad: Los premios por Medalla en Tokio Serán más del Doble que en Río. Available online: https://www.marca.com/paralimpicos/2021/06/24/60d49f53e2704e2d8f8b459c.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Instituto Distrital de Recreación y Deporte. Resolución No. 406 de 2013; Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013.

- Harvey, M.W.; Rowe, D.A.; Test, D.W.; Imperatore, C.; Lombardi, A.; Conrad, M.; Szymanski, A.; Barnett, K. Partnering to Improve Career and Technical Education for Students with Disabilities: A Position Paper of the Division on Career Development and Transition. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2020, 43, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băiţan, G.F. The Invictus Games Tournament; Bulletin of ”Carol I” National Defence University: Bucharest, Romania, 2020; pp. 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedbalski, J. The Multi-Dimensional Influence of a Sports Activity on the Process of Psycho-Social Rehabilitation and the Improvement in the Quality of Life of Persons with Physical Disabilities. Qual. Soc. Rev. 2018, 14, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Paralympic Committee. Accessibility Guide. October 2020. Available online: https://www.paralympic.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/IPC%20Accessibility%20Guide%20-%204th%20edition%20-%20October%202020.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Salazar, J.P.; Figueroa, H.; Inclusion and People with Disabilities of Guadalajara. Juan Pablo Salazar (corresponding author) in direct communication with the Hector Figueroa. Personal communication, 3 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Paralympic Committee. Great Wall of China and Forbidden City Made Accessible. Available online: https://www.paralympic.org/feature/6-great-wall-china-and-forbidden-city-made-accessible (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- International Paralympic Committee. Sochi 2014 Breaks down Barriers. Available online: https://www.paralympic.org/feature/8-sochi-2014-breaks-down-barriers (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Government of Japan Universal Design Action Plan. 2017. Available online: https://japan.kantei.go.jp/97_abe/actions/201702/20article2.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Kerr, S. The London 2012 Paralympic Games. In the Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies; Brittain, I., Beacom, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 481–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John Armstrong Research Ltd.; LOCOG. Post Games Attitudes to Disability. Consultant’s Report. 2012; Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, J.P. Juan Pablo Salazar (corresponding author) in direct communication with BP and Chanel 4. Personal communication, 10 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Roosevelt, E. United Nations Speech Where Do Human Rights Begin; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1958.

- UNESCO Chair MTU. Human Rights in and through Sport. Available online: http://sportandhumanrights.unescoittralee.com/index.php/homepage (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Medicins du Monde. The KAP Survey Model. 2011. Available online: https://www.medecinsdumonde.org/en/actualites/publications/2012/02/20/kap-survey-model-knowledge-attitude-and-practices (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- About the International Paralympic Committee. Available online: https://www.paralympic.org/ipc/who-we-are (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Virtus. Who We Are. Available online: https://www.virtus.sport/about-us/who-we-are/who-we-are (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Hughes, C.; McDonald, M.L. The Special Olympics: Sporting or Social Event? Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2008, 33, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammons, D. An Insight into the World Deaf Sport Organization. Achieve Magazine. 2006, pp. 18–20. Available online: http://www.ciss.org/an-insight-into-the-world-deaf-sport-organization (accessed on 15 June 2021).

| A form of social prejudice that suggests people with disabilities are inferior to their “able-bodied” counterparts. |

| It aligns with a human rights approach and the social model of disability. |

| Refers to changes in the way people approach adaptive sports |

| Focus excessively or repeatedly on an athlete’s body, thus putting disability in the body. |

| The portrayal of people as inspirational solely because of their disability. |

| Use of problematic or discriminatory language. |

| References the barriers affecting people with disabilities |

| The trendsetters | The most engaged and well-informed athletes that are actively pursuing to put their entire platform at the service of inclusion. |

| The followers | Not as engaged as trendsetters because they do not have the time or the resources but are still interested and participate when they can. |

| The base | Know a bit about the social and human rights model of disability but are not engaged because they just do not care or identify as advocates. |

| 12–18 yrs. | 19–29 yrs. | |

|---|---|---|

| Amateurs | 4 men | 3 men |

| 2 women | 2 women | |

| Paralympians | 5 men | 4 men |

| 2 women | 2 women |

| Nodes | LAC | UK | US | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ableism | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Appropriate message | 3 | 11 | 8 | 22 |

| Cultural shift | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Emphasis on the body | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| Inspiration Porn | 22 | 9 | 15 | 46 |

| Non-inclusive language | 6 | 5 | 8 | 19 |

| Raising awareness | 0 | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| Nodes | LAC | UK | US | All Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ableism | 0% | 7% | 7% | 4% |

| Appropriate message | 10% | 30% | 27% | 22% |

| Cultural shift | 0% | 3% | 13% | 6% |

| Emphasis on the body | 3% | 7% | 13% | 8% |

| Inspiration Porn | 37% | 23% | 33% | 31% |

| Non-inclusive language | 17% | 13% | 23% | 18% |

| Raising awareness | 0% | 10% | 17% | 9% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carty, C.; Mont, D.; Restrepo, D.S.; Salazar, J.P. WeThe15, Leveraging Sport to Advance Disability Rights and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111738

Carty C, Mont D, Restrepo DS, Salazar JP. WeThe15, Leveraging Sport to Advance Disability Rights and Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):11738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111738

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarty, Catherine, Daniel Mont, Daniel Sebastian Restrepo, and Juan Pablo Salazar. 2021. "WeThe15, Leveraging Sport to Advance Disability Rights and Sustainable Development" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 11738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111738