Abstract

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the status of emotional labor and its related factors among nurses in general hospital settings in Korea. A total of seven electronic databases were comprehensively searched to find relevant cross-sectional studies published up to 28 January 2021. The meta-analysis was performed using Stata version 13.1. In total, 131 studies were included. The population showed a standardized mean difference of 3.38 (95% confidence interval, 3.34 to 3.42) in emotional labor assessed by a 1–5 Likert scale. The level of emotional labor had significant negative correlations with job satisfaction, social support, organizational engagement, coworker support, resilience, and nurses’ work environment, while it had significant positive correlations with emotional labor and burnout, turnover intention, and job stress. Although the methodological quality of the included studies was generally good, 24 of the included studies (18.32%) were evaluated as lacking generalization potential or otherwise as unclear. In conclusion, nurses in general hospital settings in Korea experience mild-to-moderate levels of emotional labor. There is some evidence that the emotional labor of nurses and its detrimental effects can be buffered at both the individual and hospital levels, and future research should focus on developing targeted interventions and evaluating their effectiveness.

1. Introduction

Nurses are important healthcare workers (HCWs) and are potentially exposed to occupational stressors, including poor coworker attitudes, working in busy departments, inadequate pay, overwork, and possible tensions/conflicts with other medical staff [1]. Many studies have reported that burnout, including low personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion, is common in this population [2], causing nurses’ quality of life and well-being to be threatened [3,4]. Not only is the improvement of nurses’ mental health important to enhance their overall health and quality of life [3], but also their good mental health is essential for patient safety [5,6] and the efficient use of medical resources, such as organizational commitment and productivity [6]. For example, HCWs’ turnover intention, which is known to be related to emotional labor [7], has also been connected to significant financial costs and reduced productivity [8].

Emotional labor can be defined as the process of managing emotions such that they are appropriate for organizational or professional display expectations [9], which can occur in any occupation that provides interpersonal services, including nursing. Four dimensions of emotional labor were conceptualized by Morris and Feldman, which include emotional dissonance, variety of emotions to be displayed, attentiveness to required display rules, and frequency of appropriate emotional display [10]. These dimensions are focused on external behavioral displays. On the other hand, Yang et al. has suggested that the major dimensions of emotional labor include: emotion termination, expression of naturally felt emotions, surface acting, and deep acting [11]. Emotional labor is known to have a harmful impact on the health of various occupational workers, and in the case of nurses, it is associated with an increased risk of musculoskeletal problems, burnout, and depression [12]. However, some studies have emphasized the bright side of emotional labor, and in particular, it has been suggested that deep acting, but not surface acting, has a positive relationship with outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, job performance, and customer satisfaction in general [13,14]. In other words, it is not assumed that emotional labor will have a negative impact on individual well-being as a whole, but it is suggested that an approach according to its subtype is needed.

Korea’s medical services are over-crowded, and nurses in Korea are required to take on high levels of emotional labor and work intensely. The job demands-resources model proposed by Demerouti and colleagues presents the contributing factors of job burnout and job engagement that can be applied to various occupational environments, including nursing [15]. Job demands refer to physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological effort or skills [15], and in particular, psychological demands can be conceptualized as emotional labor that can lead to emotional exhaustion [16]. A recent integrative review found three key job demands of nursing staff: work overload, lack of formal rewards, and work–life interference, and six key job resources: supervisor support, fair and authentic management, transformational leadership, interpersonal relations, autonomy and professional resources [17]. Therefore, elucidating the relationship between these job demands and resources and emotional labor can be utilized to improve the nursing environment with regards to maintaining good mental health and well-being as well as for improving the emotional labor and exhaustion of nurses at the organizational level.

A systematic review is a research methodology that answers clinical questions by systematically and comprehensively collecting existing literature [18]. By using this methodology, investigating the level of emotional labor and related factors of Korean nurses may help to improve not only the emotional labor, individual health, and quality of life of this population, but also patient safety and the efficient use of medical resources in Korea. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to investigate the status of emotional labor among nurses in general hospital settings in Korea. In addition, the factors associated with emotional labor among nurses were summarized.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses [19] (Supplementary File S1). The protocol of this systematic review was registered in the Open Science Framework registry (doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/R8GKF), and the protocol was followed.

2.1. Study Search

Comprehensive study searches were conducted in seven electronic databases, including four international databases (MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE (via Elsevier), the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and PSYCARTICLES) and three domestic databases (Korea Citation Index, Research Information Sharing Service, and Koreanstudies Information Service System). To identify gray and potentially missing literature, Google Scholar was manually searched. The search date of this review was 28 January 2021. All published studies up to the search date were considered. The study search process was conducted by one researcher (Lee B), with the search strategies presented in Supplementary File S2.

2.2. Study Selection

Two independent researchers (Ha DJ and Park JH) selected the studies using a two-step screening. First, the relevance of each study was determined by reviewing the title and abstract. Next, the full text of potentially relevant articles was reviewed for final inclusion. Any disagreement between the two researchers was resolved through discussion under the intervention of a third-party researcher (Kwon CY). The inclusion criteria for this review were as follows. (1) Study design: Only cross-sectional studies were included. There were no restrictions on the publication language. (2) Population: Nurses working in general hospital settings in the Republic of Korea. Studies that assessed the emotional labor of combined groups of HCWs (i.e., doctors, nurses, and other allied health practitioners) but that included separate data on nurses were considered for inclusion. There were no restrictions on the ethnicity, age, or sex of the participants. (3) Outcomes: The primary outcome included the level of emotional labor, assessed using validated assessment tools, such as the emotional labor scale by Brotheridge and Lee [20]. In addition, factors related to emotional labor, including individual personalities, job satisfaction, health outcomes, intent to leave, nursing performance, and patient safety were investigated.

2.3. Risk of Bias (Methodological Quality) Assessment

Among the included studies, the methodological quality was assessed by two independent reviewers (Ha DJ and Park JH) using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [21]. The STROBE statement consists of a 22 item checklist for an article’s title and abstract, and the introduction, methods, results, discussion sections, and other information [21]. This tool can be used to assess the risk of bias in three study designs: case-control studies, cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies. In this review, six criteria based on the STROBE statement were used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies [22]. The criteria were: (1) Are there any clear descriptions of the study settings? (2) Is sufficient information about the participants presented? (3) If the outcome is a medical diagnosis, are the criteria specified? (4) Is there a description of whether the participants provided informed consent? (5) Are there any descriptions of consecutive participants? (6) Can these results be generalized to nurses in Korea? Any disagreement between the two researchers was resolved through discussion under the intervention of a third-party researcher (Kwon CY).

2.4. Data Extraction

The following data from the included studies were extracted and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet: publication year, name of lead author, information for risk of bias assessment, sample size, mean age, ward in which the participants worked, pathological condition of participants, outcomes, and results.

2.5. Data Analysis

In our prior protocol, when considering the heterogeneity of potentially included studies, quantitative synthesis was not planned, but there was consensus among researchers that quantitative synthesis was possible in the process of actual systematic review. Therefore, meta-analyses of emotional labor among nurses in general hospital settings in the Republic of Korea were performed in this review. However, the meta-analysis was separated according to the score unit (i.e., Likert scale range). All meta-analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, USA). In the analysis, metan code was used to generate forest plots [23]. A generated forest plot provides the pooled effect size and 95% confidence interval (CI) of individual studies, helping to easily identify intra-study and inter-study variations. The results were presented as standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. Since substantial heterogeneity was anticipated, a random-effects model, which incorporates an estimate of heterogeneity into the weighting, was introduced [23,24]. Specifically, the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method was used [23]. The heterogeneity was assessed with the I-square statics [25,26]. As suggested by Higgins et al., in this review, an I-square value greater than 75% was considered high heterogeneity [25]. In addition, the emotional labor-related factors among nurses were investigated. Specifically, correlation results between emotional labor and other variables were extracted from the included studies, and the number of reported variables was quantified. In addition, considering that deep acting has been reported to have a positive relationship with some outcomes of individual mental health and well-being in previous studies [13,14], we tried to investigate whether it is consistently reported in Korean nurses as well.

2.6. Publication Bias

Publication bias was investigated using a funnel plot if more than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Metafunnel code was used to generate the funnel plots [27]. When the effect size and standard error are entered into the metafunnel code, a funnel plot is created. By examining the visual symmetry of this plot, the publication direction can be evaluated [27].

3. Results

3.1. Study Search

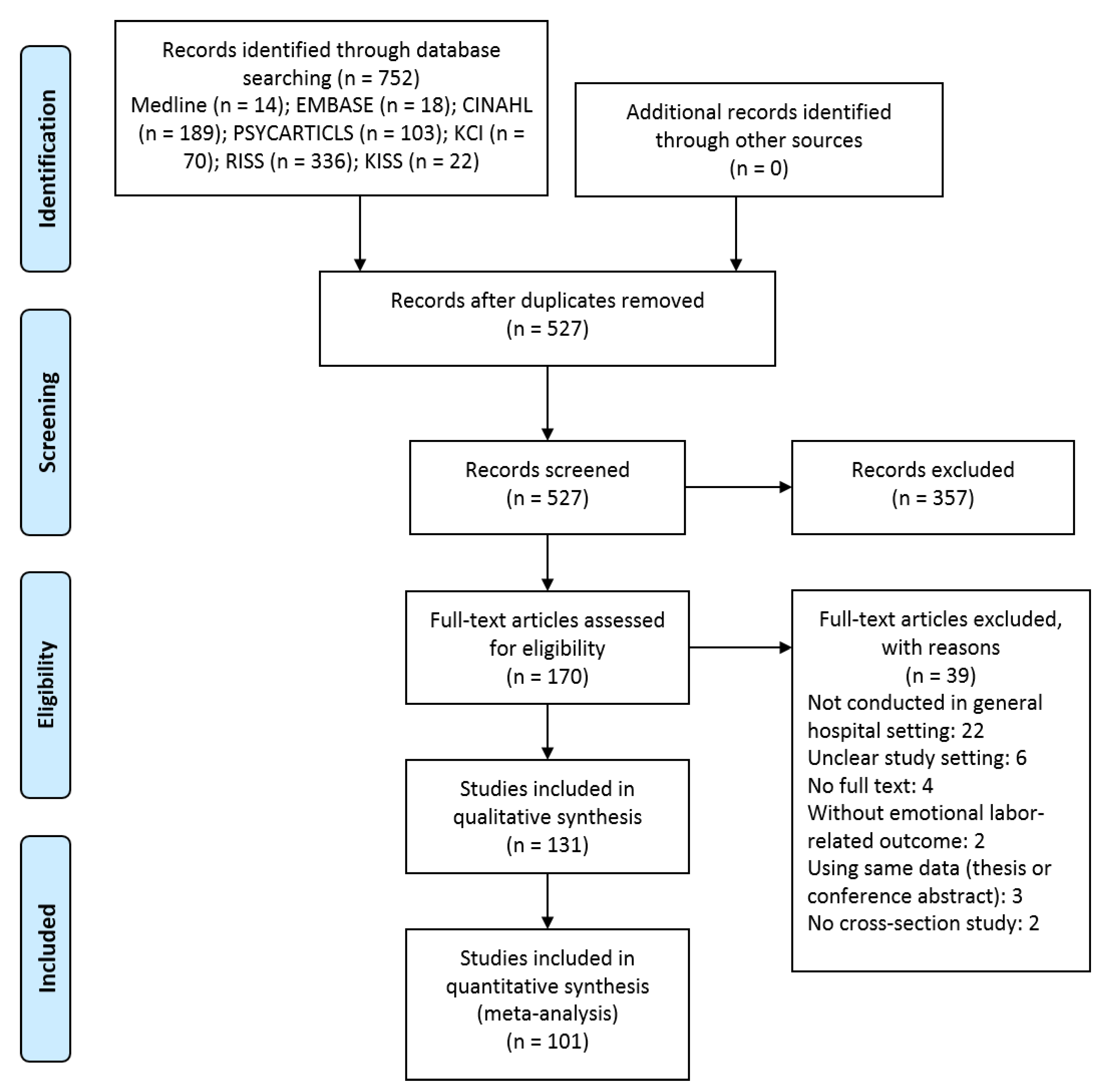

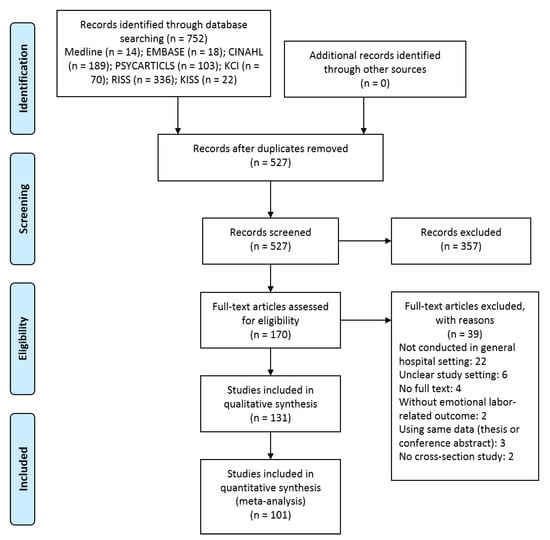

As a result of the literature search, 527 studies were searched, excluding duplicates. Among them, 172 potentially relevant articles were selected for the first screening process. As a result of the secondary screening of the full texts, 22 which were not conducted in general hospital settings [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], 6 which did not confirm the hospital where the research had been conducted [49,50,51,52,53,54], 4 which did not include the full text [55,56,57,58], 2 which did not use emotional labor [59,60], 3 which used the same data as other journal articles (thesis or conference abstract) [61,62,63], and 2 studies that did not have cross-section designs [64,65] were excluded. Finally, 131 studies were included in this review [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196]. Among these, 101 studies were included in the meta-analysis [67,68,69,71,74,77,78,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,94,96,97,98,100,102,103,104,105,106,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,128,129,130,131,132,133,136,137,139,141,142,143,144,145,147,148,149,150,151,152,154,155,156,157,158,159,161,162,164,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,174,175,176,178,180,181,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,192,193,194,195] The PRISMA flow chart for this review is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of this review. Abbreviations. CINAHL, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature; KCI, Korea Citation Index; KISS, Koreanstudies Information Service System; RISS, Research Information Sharing Service.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

In total, 131 studies had cross-sectional designs [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197]. These studies were all published between 2009 and 2020 and were conducted on Korean nurses (only the nursing staff) in Korea. The analyzed sample sizes of the included studies varied from 60 to 813. In 38 studies [69,70,72,73,75,77,82,90,93,101,104,112,113,129,130,131,134,138,141,147,148,149,153,154,161,163,166,167,169,171,173,174,175,176,187,191,194,195], the sex of the participants was not reported. It is presumed that sex information was missing under the assumption that all participants were female. One study included only male nurses [190]. The participants in the remaining studies were either all or mostly female. In 15 studies [72,74,75,92,96,122,131,134,139,143,145,146,153,160,164], information regarding which departments the participants worked in was not reported. Six studies included only nurses working in emergency departments [98,109,118,127,148,178], one study included only nurses working in intensive care units [137], two studies included only hospice nurses [161,181], and one study included only nurses working in comprehensive nursing care wards [177]. In the remaining study, nurses working in various departments were included. In 59 studies [66,67,72,74,75,78,80,82,83,87,88,89,95,98,99,100,101,102,105,106,107,109,111,116,118,121,122,123,129,130,131,134,136,137,139,143,145,148,151,152,153,155,159,160,161,163,164,165,166,168,169,177,178,179,181,188,191,193,196], whether the participants performed shift work was not reported. Four studies only included nurses who did not have shift work [79,86,103,192], while four other studies only included nurses with three shifts [81,170,175,186]. In the remaining studies, nurses with and without shift work were included (Supplementary File S3).

3.3. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

The included studies all presented a clear description of the study setting. Only one study [153] did not clearly describe the study population. Not all of the studies needed to present diagnostic criteria because they did not use medical diagnosis as an outcome. Seven studies [76,110,116,150,153,173,179] did not mention receiving consent from participants. None of the included studies mentioned targeting consecutive participants. In the generalization of the study domain, 50 studies [66,67,72,74,75,78,82,83,87,88,89,92,96,99,100,101,102,105,106,107,109,111,116,121,122,123,129,130,131,136,139,143,145,146,151,152,153,155,159,160,163,164,165,166,168,169,188,191,193,196] were rated as unclear because they lacked information on nurses’ working departments and/or shift work. Eighteen studies that targeted only nurses who worked in specific departments, including outpatient departments [103], emergency [80,98,118,127,148,178], hospice wards [161,181], health examination centers [191], intensive care [68], comprehensive nursing care [177], and three-shift [81,170,175,186], or no shift rotations [79,86]; another six studies with restrictions on their clinical experience [76,144], sex [190], or age [91,126,179] were rated as no (Supplementary File S3).

3.4. Main Results

3.4.1. Status of Emotional Labor among the Participants

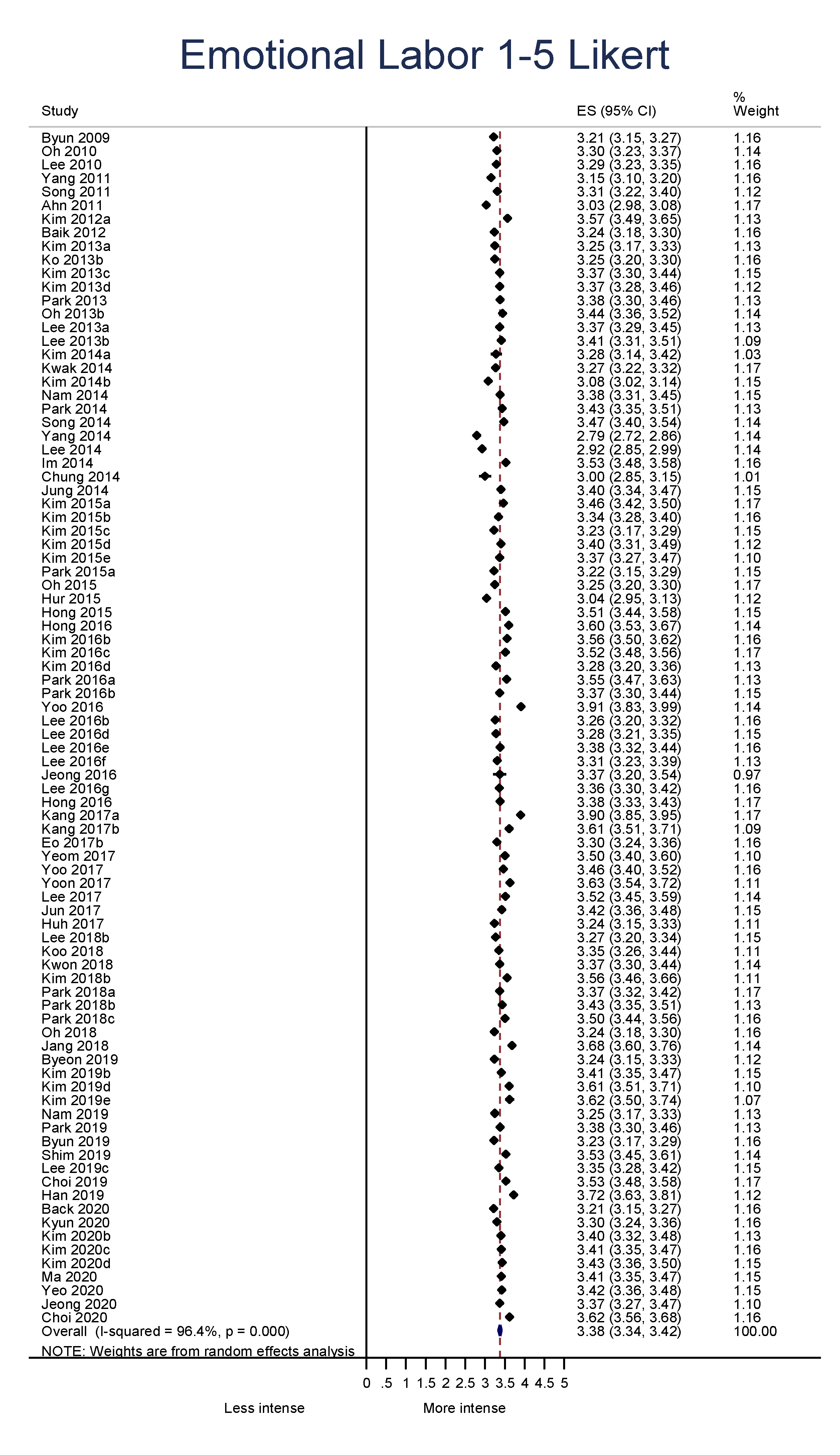

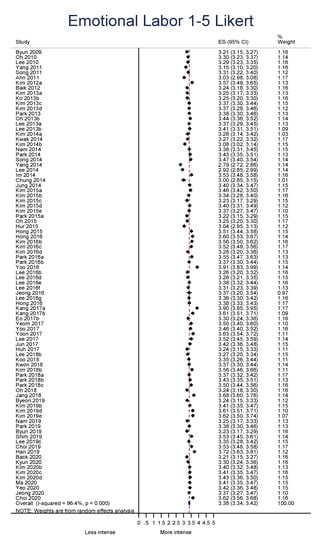

Meta-analyses for outcomes of emotional labor from a 1–5 Likert scale were as follows: total score of emotional labor (88 studies; SMD, 3.38; 95% CI, 3.34 to 3.42; I2 = 96.4%), frequency of emotional display (57 studies; SMD, 3.55; 95% CI, 3.51 to 3.59; I2 = 94.8%), attentiveness to required display rules (55 studies; SMD, 3.34; 95% CI, 3.29 to 3.40; I2 = 97.0%), emotional dissonance (57 studies; SMD, 3.15; 95% CI, 3.10 to 3.21; I2 = 96.9%), variety of emotional display (4 studies; SMD, 3.51; 95% CI, 3.44 to 3.58; I2 = 68.8%), duration of emotional display (1 study; SMD, 3.36; 95% CI, 3.25 to 3.47), level of emotion caution (1 study; SMD, 3.36; 95% CI, 3.29 to 3.43), emotional modulation efforts in profession (8 studies; SMD, 3.70; 95% CI, 3.61 to 3.79; I2 = 91.5%), patient-focused emotional suppression (8 studies; SMD, 3.21; 95% CI, 3.11 to 3.31; I2 = 84.0%), emotional pretense by norms (8 studies; SMD, 3.23; 95% CI, 3.14 to 3.33; I2 = 89.9%), surface acting (13 studies; SMD, 3.29; 95% CI, 3.18 to 3.41; I2 = 96.3%), and deep acting (13 studies; SMD, 3.39; 95% CI, 3.27 to 3.51; I2 = 96.9%). Meta-analyses for outcomes of emotional labor from a 1–7 Likert scale were as follows: total score of emotional labor (three studies; SMD, 4.57; 95% CI, 4.29 to 4.84; I2 = 94.8%), surface acting (SMD, 4.66; 95% CI, 4.53 to 4.79), and deep acting (SMD, 4.39; 95% CI, 4.27 to 4.51). Finally, meta-analyses for total scores for emotional labor from a 1–4 Likert scale were conducted (one study; SMD, 2.79; 95% CI, 2.73 to 2.85) (Figure 2, Supplementary File S4).

Figure 2.

Emotional labor (1–5 Likert) among Korean nurses. Note: The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method, which incorporates an estimate of heterogeneity into the weighting, was used.

3.4.2. Factors Related to Emotional Labor among the Participants

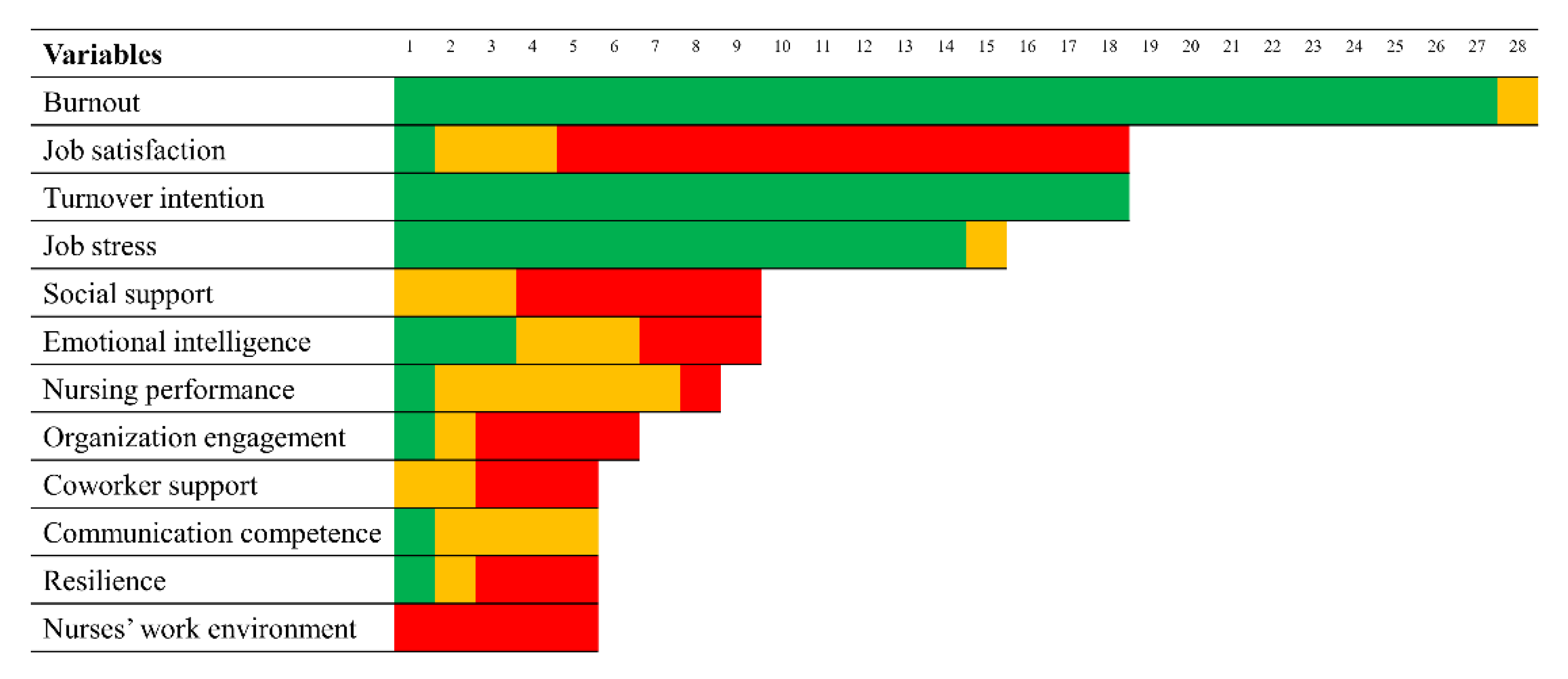

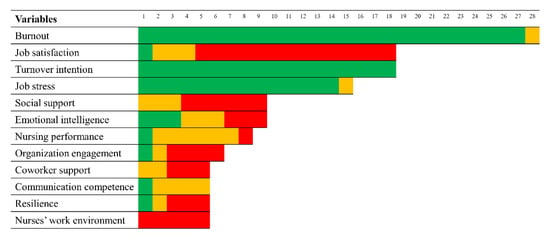

In 116 studies [67,68,69,70,71,73,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,98,100,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,180,181,182,183,184,186,187,188,189,190,191,193,194,195,196], the relationships between emotional labor or its subscales and other variables were analyzed. Among the studies, 23 studies [67,69,70,79,80,81,87,89,94,107,112,119,127,131,135,148,153,161,162,164,174,188,191,195] were excluded, as these studies only reported the relationships between the subscales of emotional labor and other variables. In total, the relationships between emotional labor and a total of 63 variables were analyzed. Among them, 12 variables commonly reported in five or more studies were, in order of frequency, burnout, job satisfaction, turnover intention, job stress, social support, emotional intelligence, nursing performance, organization engagement, coworker support, communication competence, resilience, and nurses’ work environment. Overall, significant negative correlations were reported between emotional labor and job satisfaction, social support, organizational engagement, coworker support, resilience, and nurses’ work environment. On the other hand, significant positive correlations were reported between emotional labor and burnout, turnover intention, and job stress. The relationships between emotional labor and other variables were either unclear or were not statistically significant (Figure 3, Supplementary File S5).

Figure 3.

Factors related to emotional labor among the participants. Note: Green indicates statistically significant positive correlation; yellow indicates no statistical significance; red indicates statistically significant negative correlation.

Among the studies reporting the relationships between emotional labor and other variables, 12 studies [69,70,81,87,93,94,103,112,119,148,149,170] divided emotional labor into surface acting and deep acting. Surface acting and deep acting showed contradictory associations in some variables. Specifically, job stress, burnout, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, psychosocial stress, presenteeism, anxiety, and frustration were all reported to have significant positive associations with surface acting, whereas no significant or significant negative associations with deep acting were reported. On the other hand, self-efficacy, authentic leadership, enjoyment, pride, job satisfaction, and job embeddedness were not observed to have significant associations with surface acting, but they were reported to have significant positive relationships with deep acting (Table 1).

Table 1.

The relationships between surface acting or deep acting and other variables.

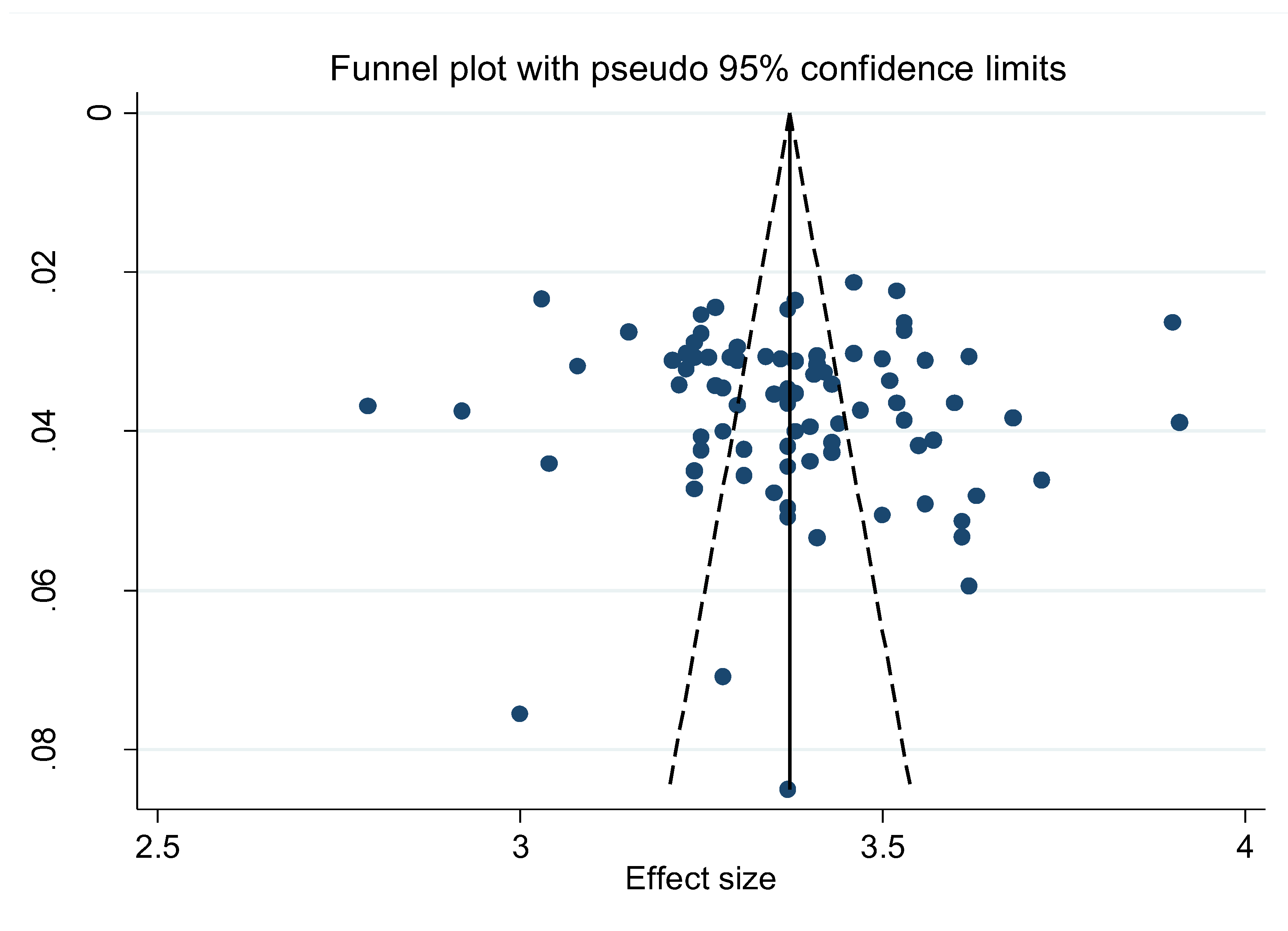

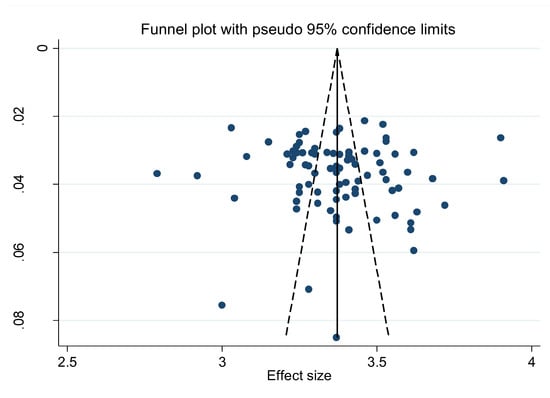

3.5. Publication Bias

Funnel plots of six outcomes, including emotional labor, frequency of emotional display, attentiveness to required display rules, emotional dissonance, surface acting, and deep acting (all of which used a 1–5 Likert scale) were generated. Although no apparent publication bias was observed in the funnel plot for emotional labor, moderately sized studies that fell outside of the funnel shape were considered outliers (Figure 4). This tendency was also observed in the funnel plots for frequency of emotional display, attentiveness to required display rules, emotional dissonance, surface acting, and deep acting (Supplementary File S6).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot for emotional labor (1–5 Likert) among Korean nurses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

This systematic review was performed to investigate the status of emotional labor among nurses in general hospital settings in Korea. According to the meta-analysis, the population was reported to have experienced mild-to-moderate levels of emotional labor (3.38 of SMD, 1–5 Likert scale). Other subscales of emotional labor showed similar levels (from 3.15 in emotional dissonance to 3.70 in emotional modulation efforts in profession, 1–5 Likert scale). Several studies have further investigated the relationships between emotional labor and other variables. Significant negative correlations were reported between emotional labor and job satisfaction, social support, organizational engagement, coworker support, resilience, and nurses’ work environment. However, significant positive correlations were reported between emotional labor and burnout, turnover intention, and job stress. The relationships between emotional labor and other variables were either unclear or not statistically significant. As suggested in previous studies [13,14], job stress, burnout, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, psychosocial stress, presenteeism, anxiety, and frustration were all reported to have significant positive associations with surface acting but not with deep acting, while self-efficacy, authentic leadership, enjoyment, pride, job satisfaction, and job embeddedness were reported to have significant positive associations with deep acting but not with surface acting. Although the methodological quality of the included studies was generally good, 24 of the included studies (18.32%) lacked generalization potential or were too unclear to evaluate.

4.2. Clinical Implications

In clinical practice, nurses experience emotional labor due to the nature of their jobs, where they have to listen to patients’ complaints and maintain a helpful attitude. However, emotional labor is associated with an increased risk of musculoskeletal problems, burnout, and depression [12]. According to our findings, Korean nurses experienced mild-to-moderate emotional labor. However, the significant heterogeneity found in the meta-analysis suggests that the level of emotional labor may have differed depending on the working environment. As expected, emotional labor showed significant negative correlations with job satisfaction, social support, organizational commitment, health promotion behaviors, and resilience, while it showed significant positive correlations with job stress, burnout, turnover, and depressive symptoms.

However, since these findings are all based on the results from cross-sectional studies, these associations do not explain causal relationships. Some included studies allow us to infer relationships between them, which may broaden our understanding of the effects of emotional labor on nurses. Emotional intelligence can be defined as “the ability to identify, understand, and use emotions positively to manage anxiety, communicate well, empathize, overcome issues, solve problems, and manage conflicts [197].” As emotional intelligence is known to buffer the detrimental effects of customer incivility in service occupations [198], this could potentially be related to nurses. Among the included studies in this review, Baik, using hierarchical multiple regression and path analysis, suggested that high levels of support could buffer the effect of emotional labor on burnout [133]. In addition, in that study, nurses with lower levels of emotional intelligence had a stronger association between emotional labor and burnout [133]. Hong et al. used structural equation modeling to analyze their hypothetical model’s goodness of fit and found that emotional intelligence mediated the relationship between emotional labor and burnout [71]. Specifically, burnout was significantly affected by emotional labor, job stress and emotional intelligence (with a total explanatory power of 37.2%), and emotional intelligence was significantly affected by emotional labor and job stress (with a total explanatory power of 13.1%) [71]. However, Hwang reached slightly different conclusions [196]. In their study, analysis using the Sobel test and hierarchical regression analysis showed that emotional labor was a mediating factor between emotional intelligence and burnout [196]. Emotional intelligence in nurses may be an important factor in the relationship between emotional labor and burnout. Since it is known that emotional intelligence can be improved through training [199], educational programs targeting emotional intelligence are not only expected to improve nurses’ general health [200], leadership [201], and quality of nursing care [202], but also buffer the effects of emotional labor’s triggering of burnout. As burnout has been found to be a partial mediator of the effects of emotional labor on both depression [135] and turnover intention [67] in Korean nurses, these programs have the potential to have a protective effect on depression and turnover among nurses.

At the individual level, some other factors may have a protective effect against the detrimental effects of emotional labor. Among the studies included in this review, Byeon et al. and Jung et al. found that resilience can mediate the relationship between emotional labor and job satisfaction [68] and the relationship between emotional labor and depression [74], respectively. Lee et al., using structural equation modeling and path analysis, found that enjoyment, pride, and anger mediated the relationship between deep acting and job satisfaction [81]. Yeo used stepwise multiple regression and found that positive psychological capital partially mediated the relationship between emotional labor and job satisfaction [150]. These findings show that an individual’s positive psychological capital, including resilience, can mitigate the detrimental effects of the emotional labor of nurses. On the other hand, based on the affective events theory [203], emotional experiences such as mistreatment by patients in the work environment can potentially have detrimental effects by influencing nurses’ attitudes toward their jobs and their organizational behavior. According to the findings of this review, verbal violence and physical threats were reported to be positively correlated with emotional labor, while job satisfaction showed a negative correlation with the emotional labor of Korean nurses (Supplementary File S6). Some aspects of emotional labor, such as the suppression of one’s emotions or attempts to identify one’s inner self with the desired emotions, can be considered as a kind of emotional experience of nurses at workplaces. Therefore, strategies to minimize negative affective events such as violence and to enhance job satisfaction can be considered in order to reduce the harmful effects of emotional labor in this population.

The mode of emotional expression also seems to be an important factor related to the effect of emotional labor on nursing care. Ko et al. used multiple regression and found that emotional dissonance was a mediating factor between surface acting of emotional labor, but not between deep acting and burnout [69]. Surface acting can be defined as when “employees modify their displays without shaping inner feelings”, while deep acting as when “employees modify internal feelings to be consistent with display rules [204].” Gross has categorized emotional regulation strategies as antecedent-focused and response-focused emotion regulation strategies, with the former relating to reappraisal and the latter to suppression [205]. Although both of these strategies may be effective in reducing emotion-expressive behavior, reappraisal reduces disgust experience, whereas suppression is associated with sympathetic activation and has the potential to have detrimental health effects [205]. Surface acting and deep acting of emotional labor can be understood in the context of suppression and reappraisal, respectively [9]. According to the path analysis conducted by Han et al., deep acting directly and indirectly increases levels of service delivery and customer orientation, whereas surface acting indirectly decreases these [70]. Kim used multiple regression and found that the frequency of emotional expression and emotional incongruity negatively affects job satisfaction, whereas the level of emotional expression positively affects it [104]. Lee et al. (2018b) used hierarchical regression and the Sobel test and found that emotional modulation efforts buffered the effects of customer orientation on posttraumatic growth [80]. In other words, emotional labor can affect nurses’ attitudes toward patients, including their customer orientation, and some emotional expression-related factors such as emotional dissonance, surface acting, and emotional modulation efforts may mediate this effect, but these factors are also related to the work environment. Therefore, some Korean researchers have suggested that it would be promising to develop interventions that improve deep acting and work engagement in order to reduce the adverse effects of emotional labor in clinical nursing settings [70]. These suggestions are consistent with previous studies that have found that deep acting, but not surface acting, which is one aspect of emotional labor, can have a positive effect on individual mental health and well-being [13,14]. The findings of the present review emphasize that, as a whole, deep acting in Korean nurses is positively related to variables such as self-efficacy, authentic leadership, enjoyment, pride, job satisfaction, and job embeddedness (Supplementary File S6). Therefore, as well as lowering the overall emotional labor level in this population, reducing surface acting and facilitating deep acting may be a promising approach for establishing nurse mental health management strategies. Furthermore, the levels of surface acting (SMD, 3.29; 95% CI, 3.18 to 3.41) and deep acting (SMD, 3.39; 95% CI, 3.27 to 3.51) of this population found in this meta-analysis should be interpreted in this context.

Other factors at the hospital level may also be related to the impact of emotional labor. Among the studies included in this review, Oh et al. used three-step mediated regression and found that relationship-oriented culture and innovation-oriented culture partially mediated the relationship between the frequency of emotional labor and turnover intention [154]. Kim et al. used a composite-indicator structural equation model and found that workplace violence mediated the relationship between emotional labor and burnout [75]. The relationship between emotional labor and burnout can be further understood in the job demands-resources model [15]. According to the results of the included studies, the emotional labor of Korean nurses was positively correlated with workload, physical labor, work–family conflict, workplace violence, physical threats, perceived emotional requirements, emotional display rules, and demands at work, while negatively correlated with organization engagement, work engagement, nurses’ work environment, job autonomy, organization support, coworker support, and supervisor support (Supplementary File S6). These findings are consistent with the results of a recent integrative review [17], and the emotional-labor-related job demands-resources can be considered when establishing hospital-level strategies for improving the levels of emotional labor and burnout experienced by Korean nurses.

The above results suggest various factors that can be targeted at the individual and hospital levels with respect to the potentially detrimental effects of the emotional labor of Korean nurses.

4.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Studies

This study is the first to systematically analyze the emotional labor status and related factors of Korean nurses, and the findings can be used to develop strategies for improving nurses’ mental health in Korea. However, the following limitations should be considered when interpreting this study.

First, it is likely that the participants and hospital settings of the studies included in this review are heterogeneous. Although this review only targeted nurses working in a general hospital setting in Korea to minimize possible heterogeneity, the working environment may differ depending on the hospital or region. This heterogeneity of the participants and working environment may be one factor explaining the significant statistical heterogeneity of the meta-analysis conducted in this review. Differences in emotional labor among participants due to the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic cannot be ruled out, but the studies included in this review were all conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, there could have been differences in the emotional labor of nurses over time. This is because emotional labor in service jobs, including nursing, is increasingly regarded as an important social issue in Korea.

Second, the results of this review have limitations in terms of their generalizability. Since this review focuses on Korean nurses, caution must be taken when translating these results with regards to the emotional labor faced by nurses in other countries. As they live in a country still influenced by Confucian ideology, one of the typical traits of Korean nurses is to hide their thoughts or opinions, or to speak and act differently from their true intentions, as patience is considered a virtue [206,207]. However, the effect of this cultural belief on the mental health of Korean nurses has not yet been systematically investigated. In addition, since this study focused on nurses working in general hospital settings, it cannot be translated to nurses working in other medical institutions.

Third, the heterogeneity between the emotional labor evaluation tools used in the included studies was considerable. In addition, even if the same evaluation tool was cited, it was common for each study to partially modify the questions according to the working environment of the participants. Accordingly, the meta-analysis conducted in this review included research results that shared the same Likert scoring system, and the effect size was calculated using the SMD value. This is probably because nurses are not medically ill persons, so there may be no common standardized evaluation scale. Nevertheless, to develop strategies for improving the mental health of nurses in this field in the future, a standardized tool for evaluating nurses’ emotional labor is needed.

Finally, since this review only included cross-sectional observational studies, it was not possible to analyze longitudinal changes in the emotional labor status of nurses and their effects. Moreover, it was not possible to analyze which interventions may have a positive effect on emotional labor status and their effects on these nurses. However, there was a recent randomized controlled trial that used a mobile app-based stress-management program, reporting that this program reduced the emotional labor of Korean nurses [208], and a systematic review examining various interventions to reduce emotional labor in this population is also promising.

5. Conclusions

According to the findings of this review, nurses in general hospital settings in Korea, experienced mild-to-moderate levels of emotional labor. The level of emotional labor had significant negative correlations with job satisfaction, social support, organizational engagement, coworker support, resilience, and nurses’ work environment, and significant positive correlations with burnout, turnover intention, and job stress. Furthermore, it was found that some aspects of emotional labor, such as surface acting and deep acting, had different effects on this population. Specifically, job stress, burnout, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, psychosocial stress, presenteeism, anxiety, and frustration were all reported to have significant positive associations with surface acting but not with deep acting, while self-efficacy, authentic leadership, enjoyment, pride, job satisfaction, and job embeddedness were reported to have significant positive associations with deep acting but not with surface acting. Finally, there is some evidence that the emotional labor of nurses and its detrimental effects can be buffered at both the individual and hospital levels, and future research should focus on developing targeted interventions and evaluating their effectiveness.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su132111634/s1. File S1: PRISMA 2020 checklist; File S2: Search terms used for each database; File S3: Characteristics and risk of bias of the included studies; File S4: Meta-analysis results in this review; File S5: Factors related to emotional labor; File S6: Funnel plots for several outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-Y.K.; methodology, B.L. and C.-Y.K.; software, D.-J.H., J.-H.P., B.L. and C.-Y.K.; validation, C.-Y.K.; formal analysis, B.L. and C.-Y.K.; data curation, D.-J.H., J.-H.P., and S.-E.J.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-J.H., J.-H.P., and C.-Y.K.; writing—review and editing, M.-S.K., K.-L.S., Y.-H.C., and C.-Y.K.; visualization, C.-Y.K.; supervision, C.-Y.K.; project administration, C.-Y.K.; funding acquisition, C.-Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the Grand Information Technology Research Center support program (IITP-2021-2020-0-01791) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to this study is a systematic review of the original studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sharma, P.; Davey, A.; Davey, S.; Shukla, A.; Shrivastava, K.; Bansal, R. Occupational stress among staff nurses: Controlling the risk to health. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 18, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsalve-Reyes, C.S.; San Luis-Costas, C.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Albendín-García, L.; Aguayo, R.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatatbeh, H.; Pakai, A.; Al-Dwaikat, T.; Onchonga, D.; Amer, F.; Prémusz, V.; Oláh, A. Nurses’ burnout and quality of life: A systematic review and critical analysis of measures used. Nurs. Open 2021. (online published ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Watt, I.; Tsipa, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C.d.L.; Abreu, L.C.d.; Ramos, J.L.S.; Castro, C.F.D.d.; Smiderle, F.R.N.; Santos, J.A.D.; Bezerra, I.M.P. Influence of Burnout on Patient Safety: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2019, 55, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Ojemeni, M.M.; Kalamani, R.; Tong, J.; Crecelius, M.L. Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organizational outcomes: Systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 119, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.Y.; Park, H. The Effect of Nurse’s Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention: Mediation Effect of Burnout and Moderated Mediation Effect of Authentic Leadership. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2019, 49, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, J.D.; Kelly, F.; Arora, S.; Smith, H.L. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.A.; Feldman, D.C. The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X. Emotional Labor: Scale Development and Validation in the Chinese Context. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, N.; Tewogbola, P. The impact of emotional labor on the health in the workplace: A narrative review of literature from 2013–2018. AIMS Public Health 2019, 6, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, R.H.; Ashforth, B.E.; Diefendorff, J.M. The bright side of emotional labor. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Gao, J.; Chen, C.; Mu, D. How Does Emotional Labor Impact Employees’ Perceptions of Well-Being? Examining the Mediating Role of Emotional Disorder. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinman, G.; Leggetter, S. Emotional Labour and Wellbeing: What Protects Nurses? Healthcare 2016, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broetje, S.; Jenny, G.J.; Bauer, G.F. The Key Job Demands and Resources of Nursing Staff: An Integrative Review of Reviews. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Ganeshkumar, P. Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis: Understanding the Best Evidence in Primary Healthcare. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2013, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. On the dimensionality of emotional labor: Development and validation of an emotional labor scale. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Emotions in Organizational Life, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–8 August 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allagh, K.P.; Shamanna, B.R.; Murthy, G.V.; Ness, A.R.; Doyle, P.; Neogi, S.B.; Pant, H.B. Birth prevalence of neural tube defects and orofacial clefts in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Bradburn, M.; Deeks, J.; Harbord, R.; Altman, D.; Sterne, J. Metan: Fixed- and random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J. 2008, 8, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.L.; Hunter, J.E. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Harbord, R.M. Funnel plots in meta-analysis. Stata J. 2004, 4, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, M.-S.; Kim, K.-J. A Study on the effect of emotional labor and leader’s emotional intelligence on job satisfaction and organizational commitment for nurses. Korean J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, S.K.; Shin, Y.S.; Kim, K.Y.; Lee, B.Y.; Ahn, S.Y.; Jang, H.S.; Kwon, E.J.; Kim, D.H. The Degrees of Emotional Labor and the Its Related Factors among Clinical Nurses. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2009, 15, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.H. Factors affecting the burnout of nurses in cancer wards and those in general wards. Master’s Thesis, Chung-Ang University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.J.; Yoon, O.S.; Kwon, M.S.; Song, M.S. Comparison of Emotional Labor and Job Stress of Hospital Nursing Staff. Korean J. Occup. Health Nurs. 2011, 20, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Lee, E. The Relationship of Emotional Labor, Empowerment, Job Burnout and Turnover Intention of Clinical Nurses. Korean J. Occup. Health Nurs. 2011, 20, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Inn Oh, M.; Sook Kyoung, P.; Jung Mi, J. Effects of Resilience on Work Engagement and Burnout of Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2013, 19, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lim, H.N. Factors that influence the emotional labor of general duty nurses. Master’s Thesis, Dong-A University Graduate School, Busan, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eun Ju, J.; Young Chae, K.; Mun Hee, N. Influence of Clinical Nurses’ Work Environment and Emotional Labor on Happiness Index. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2015, 21, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Yang, Y.-J. Factors Affecting Job Stress of Pediatric Nurses: Focusing on Self-Efficacy, Emotional Labor, Pediatric Nurse-Parent Partnership. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2015, 21, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-O.; Wang, M.-S. A study on Emotional labor, Positive resources and Job burnout in clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2015, 16, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H. The effect of Emotional labor and Stress on Premenstrual syndrome and Menstrual pain in Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Eulji University Graduate School of Clinical Nursing, Daejeon, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, M.-H. The Effects of Work Environment, Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention by Hospital Nurses. J. Korean Clin. Health Res. 2015, 3, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shin, H.J.; Kim, K.H. Emotional, Labor and Professional Quality of Life in Korean Psychiatric, Nurses. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2015, 35, 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-M. A Study on the Effects of Emotional Labor and Emotional Intelligence on Burnout among Nurses: With a focus on A Hospital in Chungbuk, Korea. Master’s Thesis, Korea Transportation University Graduate School of Education, Chungju, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Im, M.S.; Lee, Y.-E. Factors Affecting Turnover Intention in Pediatric Nurses. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2016, 22, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jeong, H.-L.; Lim, K.-H. Effects of Emergency Department Nurses’ Emotional Labor on Professional Quality of Life—Focusing on Mediating Effects of Emotional Dissonance. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2016, 17, 491–506. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.S. Effects of hospital nurses’ Emotional, labor. Job Stress on coping, type. Master’s Thesis, DaeguHanny University Graduate School, Gyeongsan, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Song, J.-A.; Hur, M.H. Effect of Emotional Labor and Stress on Premenstrual Syndrome among Hospital Nurses. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2016, 22, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.M.; Kim, W.S.; Cho, H.H. Effects of Social Capital, Labor Intensity and Incivility on Job Burnout in Pediatric Nurses. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2017, 23, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kang, M.-J.; Ahn, H.Y.; Kim, E.-M. A Study of Pediatric Nurse’s Emotional Labor, Empowerment Pediatric Nurse-Caregiver Partnership. Asia Pac. J. Multimed. Serv. Converg. Art Humanit. Sociol. 2017, 7, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.S.; Kim, H.Y. Effects of Clinical Decision-making on Job Satisfaction among Pediatric Nurses: The Mediating Effect of the Nurse-Parent Partnership. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2018, 24, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, M.-J. The effect of the emotional quotient of emotional laborers working in a social space: On their vocational emotional satisfaction. Master’s Thesis, Kyonggi University Graduate School of Service Management, Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.J.; Kim, K.S.; Ahn, S. Effects of Emotional Labor, Nursing Organizational Culture on Self-efficacy in Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2014, 15, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. The Effect of Emotional Labor on the Quality of Life of Registered Nurses. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Shin, N. Emotional Intelligence, Emotional Labor and Exhaustion of the Clinical Nurses. Med. Leg. Update 2019, 19, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. The Influence of Gender Role Conflict and Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention of Hospital Male Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Catholic University Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-J.; Kim, E.A. Factors Influencing Turnover Intention of Nurses in Comprehensive Nursing Care Wards: Focused on Emotional Labor, Role Conflict, and Reciprocity. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 467–477. [Google Scholar]

- Wi, S.-M. Effect of Emotional Labor and Organizational Effectiveness on Nursing performance of Clinical nurses. Master’s Thesis, Gachon Medical Science University Graduate School, Incheon, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pyo, N.R. The effect of emotional dissonance and social support on job satisfaction among the general hospitals’ nurses. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, H.A. Study on Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction, and Their Effect on Turnover Intention: Focusing on Nurses at a General Hospital. Master’s Thesis, Chungnam National University Graduate School of Public Health, Daejeon, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.Y. The Effects of Job Stress and Emotional Labor on Near Miss among Nurses Working at Hospital. Master’s Thesis, Inje University Graduate School of Public Health, Gimhae, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; Kim, M.Y.; Choi, S.; Shin, H.Y. Factors Influencing Managerial Competence of Frontline Nurse Managers. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2018, 24, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.M.; Kim, E.A. Factors Influencing Musculoskeletal Disorder Symptoms in Hemodialysis Nurses in Tertiary Hospitals. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2019, 25, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. The Effects of Emotional Labor and Communication Competence on Nurse Turnover Intention. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.M. The Influences of Emotional Labor, Ethical Climate and Job Satisfaction on Retention Intention in General Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Gyeongsang National University Graduate School, Jinju, Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K.-J. Moderation and mediating effects of nursing organizational culture in relation to emotional labor, job satisfaction, and turnover intention of general hospital nurses. Master’s Thesis, Gwangju University Graduate School of Health Counseling Policy, Gwangju, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, W.; You, M. Problems and Prospects of Nursing Research on Job Stress in Korea. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2013, 19, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, S.H. Variables Related to Nursing Performance in Hospital Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Chonbuk National University General Graduate School, Jeonju, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, Y.; Han, Y.; Song, J.S.; Kim, J.S. Impact of emotional labour and workplace violence on professional quality of life among clinical nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, C.Y.; Hyun, D.S.; Jeung, D.Y.; Chang, S.J. Mediating Effects of Burnout in the Association Between Emotional Labor and Turnover Intention in Korean Clinical Nurses. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byeon, M.L.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, H.J. Resilience as a Moderator and Mediator of the Relationship between and Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction among Nurses working in ICUs. J. Korean Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 12, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.M.; Lee, A.Y. The Mediating Effect of Emotional Dissonance in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Burnout among Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2013, 19, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Han, S.-S.; Han, J.-W.; Kim, Y.-H. Effect of Nurses’ Emotional Labor on Customer Orientation and Service Delivery: The Mediating Effects of Work Engagement and Burnout. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, E.; Lee, Y.S. The mediating effect of emotional intelligence between emotional labour, job stress, burnout and nurses’ turnover intention. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2016, 22, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.-S.; Lim, S.-H. Effects of personality type on burnout in korean clinical nurses: Focus on personality type d. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Emotional Labor, Burnout and Job Satisfaction among Korean Clinical Nurses. Med. Leg. Update 2019, 19, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-S.; Baek, E. A structural equation model analysis of the effects of emotional labor and job stress on depression among nurses with long working hours: Focusing on the mediating effects of resilience and social support. Work 2020, 66, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.S.; Choe, K.; Kwak, Y.; Song, J.S. Mediating effects of workplace violence on the relationships between emotional labour and burnout among clinical nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 2331–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Park, J.H.; Park, S.H. Anger Suppression and Rumination Sequentially Mediates the Effect of Emotional Labor in Korean Nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 16, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.-M.; Joung, H.Y.; Choo, H.S.; Won, S.J.; Kwon, S.Y.; Bae, H.J.; Ahn, H.K.; Kim, E.M.; Jang, H.J. Effects of Emotional Labor, Emotional Intelligence and Social Support on Job Stress in Clinical Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Fundam. Nurs. 2013, 20, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, Y.; Jang, S.J. Nurses’ organizational communication satisfaction, emotional labor, and prosocial service behavior: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.K.; Ji, E.J. The Moderating Role of Leader-Member Exchange in the Relationships Between Emotional Labor and Burnout in Clinical Nurses. Asian Nurs. Res. 2018, 12, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.K.; Park, J.H. The mediation effect of emotional labor between customer orientation and posttraumatic growth. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jang, K.S. Nurses’ emotions, emotional labor, and job satisfaction. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2019, 13, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y. Relationship of among Emotional labor, Burnout and coping type of clinical nurses. Master’s Thesis, Gachon University Graduate School, Incheon, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.K. A study on burnout, emotional labor, and self-efficacy in nurses. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2011, 17, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.L.; Kim, J.H. Job-related stress, emotional labor, and depressive symptoms among Korean nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2013, 45, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.-R.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.-E.; Bang, Y.-Y.; Lee, G. The Influence of the Clinical Nurses’ Emotional Labor and Resourcefulness on the Turnover Intention. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, T.R. The Relationship of Nursing work and Emotional Labor among Outpatient Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Ulsan University Graduate School of Industry, Ulsan, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, T.R.; Park, J.Y. Impact of Surface and Deep Acting Emotional Labor on Emotional Dissonance among Ambulatory Care Nurses. Korean J. Health Promot. 2020, 20, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kyun, Y.-Y.; Lee, M.-A. Effects of Self-leadership, Professional Self-concept, Emotional Labor on Professional Quality of Life in Hospital Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2020, 26, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.O. Influence of Clinical Nurses’ Emotional Labor on Happiness in Workplace. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2013, 13, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.K. Emotional Labor, Emotional Intelligence, Health Promotion Behavior and Turnover Intention in Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Chodang University General Graduate School, Muan, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, J.S.; Kim, S. The Effects of Emotional Labor and Health Promotion Behavior on Premenstrual Syndrome in Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2018, 19, 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.E. A Study on Emotional Labor, Resilience and Psychological Well-Being of Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2018, 19, 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-O.; Cho, Y.-C. The Relationships between Emotional Labour and Depressive Symptoms Among Nurses in University Hospitals. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop Soc. 2013, 14, 3794–3803. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-H. Convergence Study about Influences of Emotional labor and Social support on Job Embeddedness in Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Cover. Soc. 2019, 10, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kim, S.-M.; Kwon, M.J. Factors affecting the clinical competence of new nurses. J. Ind. Converg. 2020, 18, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.-H.; Park, S.Y. Influence of Emotional Labor and Occupational Stress on Burnout of General Hospital Nurses. J. Learn. Cent. Curric. Instr. 2020, 20, 883–895. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-J. Relationship of Emotional Labor to Sleep Disturbance in Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Catholic University Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Seo, E.; Shin, S.H. The Influence of the Emotional Labor, Professional Self-Concept, Self-Efficacy & Social Support of Emergency Room Nurse’s Burnout. Stress 2019, 27, 404–412. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Choi, H. Structural equation modeling on nurses’ emotional labor including antecedents and consequences. J. Korean Data Inf. Sci. Sociaty 2016, 27, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, M.-A. Effects of Emotional Labor and Communication Competence on Turnover Intention in Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2014, 20, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-E.; Han, J.-Y. Clinical Nurses’ Job Stress, Emotional labor, Nursing Performance, and Burnout in Comprehensive Nursing Care Service Wards and General Wards. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2017, 23, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. The Effects of the Violence Experience and Emotional Labor of Hospital Nurse on the Burnout. Master’s Thesis, Changwon University, Changwon, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H. Effect of emotional labor on psychiatric health of ambulatory nurses. Master’s Thesis, Catholic University Graduate School of Public Administration, Bucheon, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-W. The influence of emotional labor on job satisfaction in univercity hospital nurses: A case study at K University Hospital. Master’s Thesis, Kyung Hee University Public School, Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H. Status of Emotional Labor and Related Factors of University Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Yeungnam University Graduate School of Environmental Health, Gyeongsan, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Seo, M. Factors Influencing the Retention Intention of Nurses in General Hospital Nurses. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-J. The Influence of a General Hospital Nurse’s Emotional Labor, Emotional Intelligence on Job Stress. J. Digit. Converg. 2014, 12, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.-K. The Relationship between Emotional Labor and Depression in Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Catholic University Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.J. Emotional labor and job exhaustion according to verbal violence in outpatient nursing staffs of university hospital. Master’s Thesis, Kyungpook National University Graduate School of Public Health, Daegu, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.H. The Effects of Emotional Labor, Empathy Competence and Job-esteem on Quality of Work Life in General Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Kyungnam University Graduate School, Changwon, Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.I. Emotional labor, job stress, and fatigue of nurses. Master’s Thesis, Kwandong University, Gangneung, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, Y.S. Effects of Emotional Labor and Self-efficacy on Psychosocial Stress of Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2015, 21, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y. The Influence of Hospital Nurses’s Emotional Labor and Job Characteristics on Empowerment. Master’s Thesis, Kyungpook National University Graduate School of Forensic Science, Daegu, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.E. The effect of emotional labor, social support and anger expression on nurses’ organizational commitment. Master’s Thesis, Kyung Hee University Public School, Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, I.K. A Study on the Emotional Labor, Burnout and Turnover Intention of Clinical Nurses. J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2014, 16, 1653–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.Y. The effect of emotional labor, job stress and way of coping on the organizational commitment of nurses in a general hospital. Master’s Thesis, Korea University Graduate School of Education, Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.O. Effects of Emotional Labor and Empathy Ability on Burnout in Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Dong-A University Graduate School, Busan, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-O. A Study on the Emotional Labor of Emergency Room Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Eulji University Graduate School of Clinical Nursing, Daejeon, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Na, S.Y. The effect of nurse’s emotional labor on turnover intention: Mediation effect of burnout and moderated mediation effect of authentic leadership. Master’s Thesis, Kyung Hee University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, M. The Effects of Emotional Labor and Positive Psychological Capital on Burnout among Nurses at a General Hospital. Master’s Thesis, Changwon University, Changwon, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, H.A. Exploration of the Relations with Emotional Labor of Clinical Nurses, Social Support, and Job Satisfaction. J. Wellness 2014, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, E.-J.; Han, K.S. Emotional Labor and its Related Factors in Nurses in the Outpatient Department. Stress 2020, 28, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.K. The correlation between perception of servant leadership, communication competence and emotional labor of hospital nurses. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University Graduate School of Nursing, Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.M.; Park, O.I.; Moon, H. The Effect of the Emotional Intelligence on the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Turnover Intention of the General Hospital Nurses. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2013, 33, 540–564. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.-Y. Effects of Emotional Labor and Job Stress on Turnover Intention among University Hospital Nurses; Chonnam National University: Gwangju, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Park, O.-I.; Moon, H. Effects of Emotional Labor on Women’s Reproductive Health of Nurses. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2015, 9, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.-S. Emotional labor of the emergency room nurse and the relationship of the turnover intention. Master’s Thesis, Soonchunhyang University Graduate School of Health Sciences, Asan, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Kim, S.; Choi, I. Effects of Emotional Labor and Job Stress on Nursing Performance and Somatic Symptoms of Nurses. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 9, 1323–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, J.A. Effects of Emotional Labor and Work Environment on Retention Intention in Nurses. Asian J. Beauty Cosmetol. 2016, 14, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Chung, S.K. Influence of Emotional Labor, Communication Competence and Resilience on Nursing Performance in University Hospital Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2016, 17, 236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.-H.; Lee, E.-K.; Kim, S.-H. Work Engagement and Associated Factors among General Hospital Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2018, 19, 462–470. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.S. The Moderating Effect of Social Support on the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Nursing Performance in General Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Kunsan University Graduate School, Kunsan, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, D.W. The Effects of Social Support and Emotional Intelligence in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Burnout among Clinical Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Chung-Ang University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Back, C.-Y.; Hyun, D.-S.; Chang, S.-J. Association between Emotional Labor, Emotional Dissonance, Burnout and Turnover Intention in Clinical Nurses: A Multiple-Group Path Analysis across Job Satisfaction. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. 2017, 47, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, C.-Y.; Hyun, D.-S.; Jeung, D.-Y.; Chang, S.-J. Burnout as a Mediator in the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Depressive Symptom in Clinical Nurses. Health Soc. Sci. 2017, 46, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.S. Factors affecting the burnout of clinical nurses: Focused on emotional labor. Master’s Thesis, Chung-Ang University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, S.W.; Ha, Y.O. Factors Influencing Nurses’ Intention to Stay in General Hospitals. Korean J. Occup. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Na, B.J.; Kim, E.J. Moderating and Mediating Effects of Work-family Conflict in the Relationship between Emotional Labor, Occupational Stress and Turnover Intention among Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 22, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, S.R.; Lee, E.K. Effects of Emotional Labor and Organizational Justice on Organizational Socialization of Emergency Room Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2017, 23, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.J.; Park, S.K.; Kong, S.S. Impact of Internal Marketing Activity, Emotional Labor and Work-Family Conflict on Turn-Over of Hospital Nurses. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2012, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.-S. Influence of Emotional Labor on Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention of Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2014, 15, 3741–3750. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.J. A study on the effect of emotional hardship on job satisfaction and turnover of nurses. Master’s Thesis, Catholic University Graduate School of Public Administration, Bucheon, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, E.-H. The Effects of Relational Bonds, Emotional Labor and Customer Orientation on Nurse Turnover Intention. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyungnam University Graduate School, Changwon, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.Y. A Study on Emotional Labor, Job Stress and Primary Dysmenorrhea among Newly Hired General Hospital Nurses; Ewha Womans University Graduate School: Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.A.; Yea, C.J.; Yeum, D.M. The Impact of Nurses’ Job Demands, Job Resources, Emotional Labor and Emotional Intelligence on Burnout. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 27, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.-Y. The Convergence Relation of Communication, Emotional Labor, and Organizational Commitment among Nurse. J. Korea Cover. Soc. 2017, 8, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.-H.; Jeoung, K.-H. Effects of Emotional Labor, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment on Turnover Intention in Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2014, 15, 7170–7178. [Google Scholar]

- Eo, Y.S.; Kim, M.S. Relationship among Emotional Labor, Emotional Leadership and Burnout in Emergency Room Nurses—Comparison of employee-focused emotional labor and job-focused emotional labor. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Uh, E.J. Associations between emotional labor and presenteeismin in nurses from tertiary hospital. Master’s Thesis, Korea University Graduate School of Education, Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, S.J. Mediating Effect of Positive Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction in Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 21, 400–409. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, E.Y. The Influence of Interpersonal Problems, Emotional Labor on Professional Self-Concept among Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Park, K.-Y. Influences of Customer Orientation, Emotional Labor, Unit manager-nurse Exchange and Relational Bonds on Nurses’ Turnover Intension. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 22, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.-M.; Kim, Y.-J. The Influence of a General Hospital Nurse’s Emotional Labor, Emotional Intelligence on Job Stress. Proc. Korea Contents Assoc. Conf. 2013, 2013, 403–404. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K.-J.; Kim, E.Y. The Influence of Emotional Labor of General Hospital Nurses on Turnover Intention: Mediating Effect of Nursing Organizational Culture. J. Digit. Converg. 2018, 16, 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y.M. A study on nurses’ emotional labor and organizational effectiveness. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University Graduate School of Public Policy, Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y.J.; Choi, Y.H. Effects of emotional labor, job stress and burnout on somatization in nurses: In convergence era. J. Digit. Converg. 2015, 13, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-A. The Effects of Nurse’s Anger-Expression Mode and Emotional Labor on Psychological Well-being and service Lebel. Master’s Thesis, Kwangwoon University Graduate School of Counseling and Welfare Policy, Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, M.H. The effects of physical labor and emotional labor on burnout and the moderating effects of social support and job autonomy among hospital nurses. Master’s Thesis, Inje University Graduate School of Public Health, Gimhae, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S.Y.; Yu, J.H. The Influence of Focusing Manner and Emotional Labor on Nursing Performance of Clinical Nurses. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2017, 23, 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.-J. The Effect of the General Hospital Nurses’ Job Satisfaction on Emotional labor and Response Level of Patients. Chung-Ang J. Nurs. 2011, 15, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.R. The relationship between Emotional Labor, Job Stress and Professional Quality of Life in Nurses working in Oncology Wards. Master’s Thesis, Kosin University Graduate School, Busan, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, S.S. Effects of Emotional Labor, Emotional Intelligence and Social Intelligence on Job stress in Clinical Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Inje Graduate University, Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.R.; Kim, J.M. Effects of Emotional Labor on Burnout in Nurses: Focusing on the Moderating Effects of Social Intelligence and Emotional Intelligence. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 22, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-A.; Kim, E. Influences of Hospital Nurses’ perceived reciprocity and Emotional Labor on Quality of Nursing Service and Intent to Leave. J. Korea Acad. Nurs. 2016, 46, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-J. Comparison of Emotional labor, Job satisfaction, Customer orientation of Nurses between Outpatient and Ward. Master’s Thesis, Gachon University Graduate School, Incheon, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.K. The Relationships of Emotional Labor, Interpersonal Problem, Burnout and Turnover Intention of Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Womans University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-J. Factors Influencing Turnover Intension of Hospital Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Gongju University Graduate School, Gongju, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-I.; Lee, E.-J. Effect of Nursing Work Environment, Emotional Labor and Ego-Resilience on Nursing Performance of Clinical Nurses. J. Wellness 2016, 11, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.N. Relation of among Emotional Labor, Burn Out and Job Involvement of Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University Graduate School of Clinical Nursing Information, Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, D.H. The Effect of Emotional Labor, Job Stress and Social Support on Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. Stress 2019, 27, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S. The Effects of New Nurses’ Job Stress, Emotional Labor and Self-Directed Learning Readines on Turnover Intention. Master’s Thesis, Dong-A University, Busan, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-Y.; Kim, J.-S. Relationships among Emotional Labor, Fatigue, and Musculoskeletal Pain in Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.Y.; Kang, H. The Influence of Emotional Labor and Resilience on Burn Out in Clinical Nurse. J. Human Resour. Manag. Res. 2020, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-J. University hospital nurse’s feelings regarding the impact on the business performance of nursing labor research. Master’s Thesis, Soonchunhyang University Graduate School of Health Sciences, Asan, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.S. A Study on the Relationships among Somatization, Emotional Labor and Burnout in Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Ajou University Graduate School, Suwon, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Im, S.-I.; Cho, E.-A. Relationship between Emotional Labor, Job Stress and Eating Attitudes among Clinical Nurses. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2014, 15, 4318–4328. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.-S.; Song, E.J. Influences of Emotional Labor, Hardiness on Job Satisfaction of Nurses in Comprehensive Nursing Care Service Units. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 21, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, E.-H. Relationships among Emotional Labor, Health Promotion Behavior and Job Satisfaction in Emergency Room Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Konyang University, Nonsan, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.Y.; Park, S.M. Effects of exposure to endocrine disruptors, burnout, and social support from peers on premenstrual syndrome in nurses. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2020, 26, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.Y. Influences of Burnout, Emotional labor, and Positive Psychological Capital on Job Satisfaction of Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2017, 23, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]