Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced people to pay more attention to the negative impacts of economic policy uncertainty on energy poverty. Meanwhile, through financial expenditure, governments might play a critical role in energy poverty alleviation, but there is little focus on this factor in the literature. We employ a panel threshold model to investigate the threshold effect of economic policy uncertainty between financial expenditure and energy poverty. This model can keenly explore the time-varying characteristics of financial expenditure. In order to control the endogenous influence, the estimators of the panel least square method are used to replace the corresponding endogenous variables. We find that financial expenditure has a significant positive effect on energy poverty alleviation, and that the positive effect has the threshold characteristic of economic policy uncertainty. With the rise in economic policy uncertainty, the positive effect of financial expenditure on energy poverty is continuously enhanced. Furthermore, we find that financial expenditure plays a more significant role in alleviating energy poverty in emerging economies than it does in developed economies.

1. Introduction

Economic policy uncertainty is considered a risk that, in the near future, remains undefined in terms of government policies and regulatory frameworks [1]. The “black swan” event, which is a term that refers to natural disasters, wars, economic crises and so on, is largely responsible for this economic policy uncertainty. The frequent occurrence of “black swan” events hinders the improvement of people’s living standards worldwide and the realization of the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At present, energy poverty has been the most significant form of poverty, posing an unprecedented challenge to global sustainable development. Although eradicating energy poverty was listed as SDG 7 in 2015, efforts to alleviate energy poverty are still hampered by various factors and this results in slow progress. By 2019, 759 million people worldwide had no access to electricity and, if the speed of energy poverty alleviation remains constant, 660 million people will still have no access to electricity by 2030. In light of this, it is natural to ask whether rising economic policy uncertainty exacerbates energy poverty. If so, how does economic policy uncertainty affect energy poverty? Exploring the answers to these questions may help to mitigate the negative impact of economic policy uncertainty on energy poverty and to achieve the SDGs.

Economic policy uncertainty has received growing scientific and political attention worldwide in recent years. Firstly, previous research focused on the assessment of economic policy uncertainty. Baker et al. (2016) developed a new index of economic policy uncertainty based on newspaper coverage frequency [2]. Davis (2016) constructed a monthly index of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty (GEPU), which is built on the work of Baker, Bloom and Davis [3]. Huang and Luk (2019) constructed a new monthly index of Economic Policy Uncertainty for China in 2000–2018, based on Chinese newspapers [4]. Secondly, the majority of research investigated the effects of economic policy uncertainty on international and domestic markets. Brogaard and Detzel (2015) found that economic policy uncertainty was an economically important risk factor for equities [5]. Zhang et al. (2019) used economic policy uncertainty in the U.S. and China to estimate the influence of both economic systems on several key international markets [6]. Song et al. (2021) examined the effects of China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) on green total factor productivity under economic policy uncertainties [7]. Thirdly, some papers explored the relationship between economic policy uncertainty and firm-level performance. Kang et al. (2014) examined the effect of economic policy uncertainty and its components on firm-level investments [8]. Jung and Kwak (2018) confirmed that the firm-level uncertainty and the macro-level economic policy uncertainty both had a negative synergy in impending enterprise investments [9]. Guo et al. (2020) analyzed the static and dynamic interactions among EPU, enterprise investments, and enterprise profitability, and then analyzed regional heterogeneity in terms of these factors [10]. Finally, a few papers have paid attention to the influence of “black swan” events on energy poverty. Oliveras et al. (2020) explored the relationship between energy poverty and health in European areas during the European debt crisis [11]. Halkos and Gkampoura (2021) assessed the impacts of the 2018 financial crisis on energy poverty in European countries and confirmed that economic recession exacerbated energy poverty in Europe [12]. Bienvenido-Huertas (2021) analyzed the effects of unemployment benefits and economic aid which was provided by the Spanish government on alleviating energy poverty during the COVID-19 lockdown [13].

Government regulation helps to mitigate the negative impacts of economic policy uncertainty. Aceleanu et al. (2015) concluded that active labor market policies focusing on job creation and green jobs for the young are effective measures to reduce youth unemployment, which is exacerbated by the financial and economic crisis [14]. Hou et al. (2021) pointed out that government subsidies could effectively mitigate the negative impact of economic policy uncertainty on energy enterprises’ finance and investment and ensure energy supply [15]. The World Bank (2020) found that the Egyptian government unleashed its potential for entrepreneurship and employment and improved social welfare through implementing financial, monetary and energy sector reforms [16]. Nguyen and Su (2021) investigated the effects of government spending on energy poverty in 56 developing countries and found that government spending has a U-shaped effect on energy poverty, and that the effect of government spending on energy poverty was transmitted through economic growth and income inequality [17]. When economic policy uncertainty rises, government actively uses various regulatory policies to stabilize employment, improve social welfare and guarantee residents’ energy demand.

Multidimensional energy poverty measurement is an effective tool in Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) methods, which is employed to assess energy poverty at a multi-country level [18,19]. Maxim et al. (2016) measured energy poverty across the European Union, by constructing the Compound Energy Poverty Indicator (CEPI) [20]. Sánchez et al. (2018) developed a method for appraising energy poverty in Spain by incorporating climatic, building and socioeconomic characteristics [21]. Gafa and Egbendewe (2021) proposed a new multidimensional measure to evaluate the levels and determinants of energy poverty in rural West Africa [22]. Halkos and Gkampoura (2021) examined energy poverty for 28 selected European countries, using a composite measurement [12]. We found that previous literature is generally limited to a particular country or region and that only rarely in the literature is global energy poverty assessed by using multidimensional energy poverty measurements. In the literature, the study by Che et al. (2021) is noteworthy as an attempt to assess global energy poverty with an integrated approach [23].

During recent years, more and more literature has focused on the impacts of threshold effects on energy poverty. Boardman (1991) defined 10% of the household’s income as a high effective threshold in energy poverty analysis [24]. Nguyen and Su (2021) pointed out that government spending has a U-shaped effect on energy poverty, implying that increases in government spending may alleviate energy poverty until a threshold is reached [25]. The panel threshold model can keenly explore the time-varying characteristics of explanatory variables and explain economic phenomena more rationally. Banerjee et al. (2021) employed a threshold regression to examine the threshold effects of the poverty headcount ratio between the energy development index and life expectancy rates, and between the energy development index and infant mortality rates, respectively [2].

Overall, these references provide some deep insights for our study. To the best of our knowledge, few papers (Oliveras et al., 2020; Halkos and Gkampoura, 2021; Bienvenido-Huertas, 2021) formally analyze the impacts of “black swan” events on energy poverty, however, they tend to ignore the impacts of economic policy uncertainty on energy poverty. We argue that, rather than accidental events (such as “black swan” events or extreme events), policy uncertainty actually has a more significant impact on the energy system, since it is quite common for economic policy changes to occur while accidental events across the local-level and global-level are infrequent. Hence, we should pay more attention to policy change-oriental effects on energy system. Furthermore, previous studies rarely investigated the role of governmental regulations in shaping the relationships between economic policy uncertainty and energy poverty. We provide empirical evidence which supports the positive effects of public financial expenditure on alleviating energy poverty. We think that this will provide some useful policy implications, particularly in the policymaking process.

Parallel to these aspects, the purpose of this study is to investigate the threshold effect of economic policy uncertainty between financial expenditure and energy poverty by using a panel threshold model. The main contributions lie in the following three aspects. Firstly, it is the first time that the panel threshold model has been employed to investigate the relationship between economic policy uncertainty, financial expenditure and energy poverty, which enriches the research on energy poverty. Secondly, the estimators of the panel least square method replace the corresponding endogenous variables to control the endogenous influence, which is effective in improving the accuracy of estimation results. Thirdly, we find that financial expenditure has a significant positive effect on energy poverty alleviation, and the positive effect has the threshold characteristic of economic policy uncertainty. With the rise of economic policy uncertainty, the positive effect is continuously enhanced. Furthermore, we find that financial expenditure plays a more significant role in alleviating energy poverty in emerging economies than it does in developed economies.

2. Methodology

2.1. Variable Description

- (1)

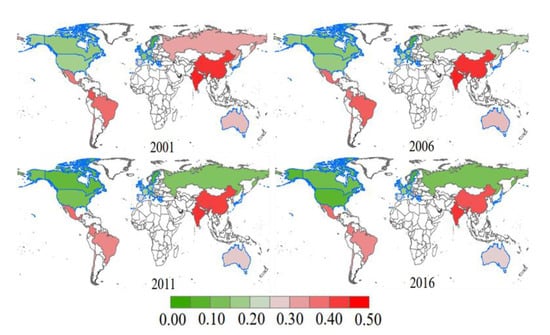

- Energy poverty. Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI) is considered as an effective measurement of energy poverty. Che et al. (2021) constructed a new three-dimensional measurement of energy poverty, including energy availability, energy affordability and energy cleanability, and assessed global energy poverty [23]. Therefore, following Che et al. (2021), we introduce their MEPI for measuring energy poverty. Figure 1 depicts the trend of MEPI from 2001 to 2016. We find that the MEPI for all of the countries shows a downward trend from 2001 to 2016, and the MEPI for emerging economics, such as China, India and Brazil, is significantly higher than that of developed economies, such as the United States of America, Canada and Japan.

Figure 1. Distributions of MEPI in 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016. Note: countries with blue border is developed economies, countries with blank is missing data, the other countries is emerging countries.

Figure 1. Distributions of MEPI in 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016. Note: countries with blue border is developed economies, countries with blank is missing data, the other countries is emerging countries.

- (2)

- Financial expenditure. Government regulation through public spending might play an important role in energy poverty alleviation, but there has been little attention paid to this factor in the literature to date [17]. The influence of financial expenditure on economic growth may affect energy poverty through its effect on energy infrastructure, energy production and utilization, income inequality and social welfare. Financial policy is the main means of economic regulation. It can quickly start investment, drive economic growth and stabilize social employment by adjusting the total amount of financial revenue and expenditure. In terms of financial expenditure, for this study we select the proportion of financial expenditure in the total expenditure as its proxy, which is collected from the WDI.

- (3)

- Economic policy uncertainty. We select the economic policy uncertainty index compiled by Baker et al. (2016) [2] to measure economic policy uncertainty. The economic policy uncertainty index quantifies newspaper coverage of policy-related economic uncertainty by calculating the frequency of articles containing keywords about economic policy uncertainty. We use panel data covering 2001–2016. A series of “black swan” events, such as the 9/11 attacks, Gulf War II, SARS epidemic, global financial crisis and European Debt Crisis, occurred during this period, which provides a reliable basis for exploring the threshold effect of economic policy uncertainty between financial expenditure and energy poverty. We adopt the geometric average method to convert monthly data of economic policy uncertainty index into annual data.

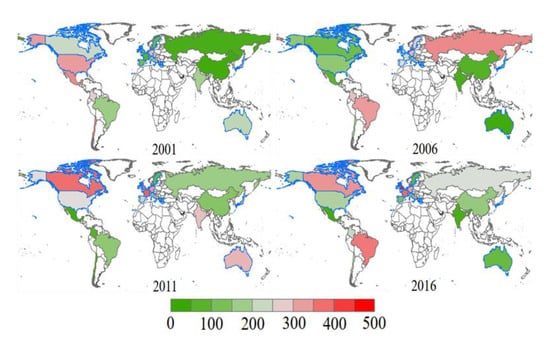

Figure 2 depicts the trend of economic policy uncertainty from 2001 to 2016. We find that the economic policy uncertainty index for the sample countries fluctuates frequently from 2001 to 2016.

Figure 2.

Distributions of economic policy uncertainty index in 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016. Note: countries with blue border is developed economies, countries with blank is missing data, the other countries is emerging countries.

- (4)

- Control variables. To effectively eliminate the interferences of countries’ heterogeneity factors, Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) are set as control variables. Governments play different roles from country to country due to institutional differences. Compared with other indicators, WGI are more comprehensive and have been used frequently in transnational studies. Therefore, we adopt the WGI to control the impact of institutional differences between countries, including voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption.

2.2. Panel Threshold Model

The effect of financial expenditure on energy poverty may be nonlinear due to economic policy uncertainty and this is shown as an interval effect. A single threshold model with economic policy uncertainty index as threshold variable is defined as:

where the explanatory variable is financial expenditure. The threshold variable is economic policy uncertainty. is the indicative function, where takes 1 if , and 0 otherwise. The control variables are voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption. Threshold variables divide samples into low economic policy uncertainty regime () and high economic policy uncertainty regime ().

Multiple thresholds may occur in this paper. We further illustrate the double threshold model briefly and the multiple threshold model can be extended based on this, specified as:

2.3. Data

Twenty-two countries in the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index database are selected as sample, including fourteen developed economies (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Spain, Singapore, the United Kingdom, the United States and Sweden) and eight emerging economies (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, India, South Korea, Russia, China and Mexico). MEPI is obtained from Che et al. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty comes from the economic policy uncertainty index database (https://www.policyuncertainty.com/index.html (accessed on 16 March 2021). Financial expenditure and control variables are obtained from the World Development Index and Worldwide Governance Indicators, respectively. MEPI and financial expenditure take the natural logarithm to reduce data skewness and avoid heteroscedasticity. Table 1 reports the definitions and summary statistics.

Table 1.

Definition and summary statistics.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Endogeneity Test and Treatment

Although the threshold parameter and quantity are completely determined by the sample, the endogeneity problem can be alleviated to a certain extent, but it cannot fundamentally be solved. Meanwhile, the threshold variable must be exogenous.

Firstly, the endogeneity test is conducted. We introduce the DWH (Du-Wu-Hausman) test for examining the endogeneity of variables, where the MEPI is set as the explained variable and the lag period of each variable is set as the instrumental variable (IV). Table 2 reports that voiacc, polsta, goveff and corcon are endogenic, while the other variables are exogenous. EPU is exogenous, which meets the panel threshold model.

Table 2.

Endogeneity test results.

Secondly, the endogeneity treatment is completed. We use the estimators of panel least square method to replace the corresponding endogenous variables, where voiacc, polsta, goveff and corcon are the explained variables, and the lagged of these variables are the explanatory variables.

3.2. Unit Root Test

In order to avoid spurious regression, we carry out unit root test for all variables with LLC test and IPS test. If the null hypothesis is rejected in both methods, the variable is considered stationary and non-stationary if otherwise. Table 3 shows that all variables reject the null hypothesis at the significance level of 10%, indicating that the original sequence data can be used for regression analysis.

Table 3.

Unit root test results.

3.3. Cointegration Test

We also employ a Kao test and Pedroni test to investigate the cointegration relationship between variables, as shown in Table 4. The results show that all variables reject the null hypothesis at the significance level of 1%, which means that there is a long-term economic relationship between the variables and that it is possible to perform the panel threshold regression.

Table 4.

Cointegration test results.

3.4. Threshold Effect Test

The threshold effect test is carried out in model (1) and model (2) respectively, and the F statistic and p value of “autonomous sampling” are shown in Table 5. According to the results, the first threshold parameter in model (1) is 120.5199, its F statistic is 27.67 and its p value is 0.0500, and therefore we reject the null hypothesis of no threshold effect. We further search for the second threshold parameter with a “grid search” in model (2). The results show that the second threshold parameter is 57.2934, F statistic is 7.91 and p value is 0.5640, which rejects the hypothesis that there are two thresholds. Therefore, the result confirms that there is a single threshold regression model, whose threshold parameter is 120.5199. The model can be represented as follows:

Table 5.

Threshold effect test results.

3.5. Full Sample Regression Analysis

Column (1) of Table 6 reports the full sample regression results with MEPI as explained variables. There is a significant negative correlation between financial expenditure and MEPI, and the impact of financial expenditure on energy poverty has a significant threshold effect on economic policy uncertainty. When financial expenditure increases by 1% under low economic policy uncertainty, energy poverty falls by 11.85%. When economic policy uncertainty is above 120.5199, the absolute value of the coefficient increases from 0.1185 to 0.1315. These results indicate that economic policy uncertainty is an important factor affecting governments’ energy poverty regulation, and the positive effect of financial expenditure on energy poverty increases with the rise of economic policy uncertainty.

Table 6.

Panel threshold regression results.

Control variables have a significant impact on energy poverty. The coefficients of voiacc, polsta and corcon are significantly positive, indicating that they have a negative impact on energy poverty. This may be because the sample countries, which only include developed and emerging economies, have a higher level of democracy and a more open domestic market, and thus they are more vulnerable to international and domestic economic policy uncertainty. The coefficients of requa and law is significantly negative, which has a positive impact on energy poverty. The sample countries have relative perfect government supervision and strict legal systems, which ensures market stability, mitigates the negative impact of economic policy uncertainty on social welfare and helps to alleviate energy poverty. The value of goveff is statistically insignificant, indicating that governments fail to provide comprehensive and effective public services in time.

3.6. Regression Analysis by Country Type

Given the economic and social differences between countries, we further identify the heterogeneous effect of the impacts of financial expenditure on energy poverty across developed economies and emerging economies by the panel threshold model.

Columns (2) and (3) of Table 6 show the regression results of developed and emerging economies, respectively. The threshold effect test shows that both columns (2) and (3) have a threshold, but that the threshold parameter of column (2) is much larger than that of column (3). This indicates that the threshold effects of developed and emerging economies are consistent with that of full sample regression, but emerging economies are more vulnerable to economic policy uncertainty. As can be seen from column (2), the coefficient of financial expenditure in developed economics is statistically insignificant. The probable reason may be that developed economies have established sound social welfare systems which can effectively mitigate the negative impact of economic policy uncertainty. The coefficient in emerging economies is significantly negative, with a larger value than that of the full sample regression. These estimated results demonstrate that financial expenditure plays an important role in alleviating energy poverty in emerging economies.

4. Robustness Tests

4.1. Alternative Energy Poverty Measurement

In this study, we change the energy poverty measurement in order to observe the robustness of full sample regression result. The sample countries include 14 developed economies and eight emerging economies, whose levels of energy poverty are mainly characterized by energy affordability. The energy affordability index (AFF) is set as an explained variable to re-run in the panel threshold model, as shown in column (4) of Table 6. According to the results, the threshold number and parameters of column (4) are consistent with that of full sample regression. The coefficient values and significances of financial expenditure in low/high economic policy uncertainty regimes are similar to those estimated using MEPI in column (1) of Table 6. It can be concluded that the regression result is robust regardless of energy poverty measurements.

4.2. Grouping Regression Analysis

We conduct a grouped regression to examine whether the threshold effect of economic policy uncertainty between financial expenditure and energy poverty is biased due to the analysis model. Referring to the threshold parameter in column (2) of Table 6, the full sample is divided into two sub-samples. According to the Hausman test, we employ a panel fixed effect model in the two sub-samples. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 7 show that the absolute value of the financial expenditure coefficient is slightly smaller than that of the full sample regression, but the coefficient is still significantly negative. This implies that the result of panel threshold model is robust and reliable regardless of the analysis model.

Table 7.

Grouping regression results.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Our study examines the threshold effect of economic policy uncertainty between financial expenditure and energy poverty from 2001 to 2016. The estimators of the panel least square method are used to replace the corresponding endogenous variables in order to control the endogenous influence. The following conclusions are obtained.

Firstly, economic policy uncertainty has threshold effects between financial expenditure and energy poverty, indicating that economic policy uncertainty has a significant impact on energy poverty. Secondly, there is an inverse relationship between financial expenditure and energy poverty. Financial expenditure has a positive effect on energy poverty alleviation, which increases as economic policy uncertainty rises. Thirdly, there are heterogeneous effects of financial expenditure on energy poverty across developed economies and emerging economies. Financial expenditure plays a more significant role in alleviating energy poverty in emerging economies than it does in developed economies.

The obtained conclusions have important policy implications.

Firstly, governments should pay close attention to economic policy uncertainty, both at home and abroad. Through the establishment of risk monitoring and early warning mechanisms, governments could release economic forecast information and help people to understand economic policy changes in a timely fashion. Secondly, it is an urgent necessity to alleviate energy poverty by optimizing financial expenditure. For instance, governments could enhance enterprise confidence, stabilize employment and ensure residents’ income by increasing government subsidies, innovating policy support and expending financing channels. Improving social welfare through mechanisms, such as an unemployment subsidy, could meet the basic energy needs of residents. Last but not least, emerging economies should pay more attention to the impact of economic policy uncertainty on energy poverty. Emerging economics could improve the rule of law to provide a stable environment for policy implementation.

In this study we employ a panel threshold model to verify the threshold effect of economic policy uncertainty between financial expenditure and energy poverty, although we are deeply constrained by data limitations. The methodology will form one instrument for analyzing the threshold effect of economic policy uncertainty and designing and implementing targeted policies in energy poverty alleviation. However, further research is necessary for predicting the potential impact of economic policy uncertainty on energy poverty, based on the indicators outlined in this paper and in order to implement effective precautionary measures to minimize the negative impact.

Author Contributions

X.C. conceived the idea, designed study, analyzed results, and revised the draft. M.J. contributed in writing and analyzing results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Our heartfelt thanks should be given to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71903099), the General Foundation of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province (2019SJA0165), and the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (19KJB610019) for funding supports.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Thaqeb, S.A.; Algharabali, B.G. Economic policy uncertainty: A literature review. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2019, 20, e00133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 1593–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J. An Index of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Luk, P. Measuring economic policy uncertainty in China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogaard, J.; Detzel, A. The asset-pricing implications of government economic policy uncertainty. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Lei, L.; Ji, Q.; Kutan, A.M. Economic policy uncertainty in the US and China and their impact on the global markets. Econ. Model. 2019, 79, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hao, F.; Hao, X.; Gozgor, G. Economic policy uncertainty, outward foreign direct investments, and green total factor productivity: Evidence from firm-level data in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Lee, K.; Ratti, R.A. Economic policy uncertainty and firm-level investment. J. Macroecon. 2014, 39, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, S.; Kwak, G. Firm characteristics, uncertainty and research and development (R&D) investment: The role of size and innovation capacity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, A.; Wei, H.; Zhong, F.; Liu, S.; Huang, C. Enterprise Sustainability: Economic Policy Uncertainty, Enterprise Investment, and Profitability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveras, L.; Peralta, A.; Palència, L.; Gotsens, M.; López, M.J.; Artazcoz, L.; Borrell, C.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M. Energy poverty and health: Trends in the European Union before and during the economic crisis, 2007–2016. Health Place 2021, 67, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkos, G.E.; Gkampoura, E.-C. Evaluating the effect of economic crisis on energy poverty in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienvenido-Huertas, D. Do unemployment benefits and economic aids to pay electricity bills remove the energy poverty risk of Spanish family units during lockdown? A study of COVID-19-induced lockdown. Energy Policy 2021, 150, 112117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceleanu, M.; Serban, A.C.; Burghelea, C. “Greening” the Youth Employment—A Chance for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2623–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hou, F.; Tang, W.; Wang, H.; Xiong, H. Economic policy uncertainty, marketization level and firm-level inefficient investment: Evidence from Chinese listed firms in energy and power industries. Energy Econ. 2021, 100, 105353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Egypt Economic Monitor, November 2020: From Crisis to Economic Transformation-Unlocking Egypt’s Productivity and Job-Creation Potential; World Bank: Bretton Woods, NH, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Su, T.D. The influences of government spending on energy poverty: Evidence from developing countries. Energy 2022, 238, 121785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhars, M.; Miah, F.; Qudrat-Ullah, H.; Kayal, A. A Systematic Review of the Relationship Between Energy Consumption and Economic Growth in GCC Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesticò, A.; Somma, P. Comparative analysis of multi-criteria methods for the enhancement of historical buildings. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maxim, A.; Mihai, C.; Apostoaie, C.-M.; Popescu, C.; Istrate, C.; Bostan, I. Implications and Measurement of Energy Poverty across the European Union. Sustainability 2016, 8, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, C.S.-G.; González, F.J.N.; Aja, A.H. Energy poverty methodology based on minimal thermal habitability conditions for low income housing in Spain. Energy Build. 2018, 169, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafa, D.W.; Egbendewe, A.Y. Energy poverty in rural West Africa and its determinants: Evidence from Senegal and Togo. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, P. Assessing global energy poverty: An integrated approach. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, B. Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth; Pinter Pub Limited: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R.; Mishra, V.; Maruta, A.A. Energy poverty, health and education outcomes: Evidence from the developing world. Energy Econ. 2021, 101, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).