Abstract

Education is considered the primary driver of sustainable development. Teachers play a critical role in the conjunction of ideal, designed, and actual teaching and learning experience delivery. Successful education plays a crucial role in accomplishing the UN Sustainable Development goals (SDGs). Therefore, this research focused on the better preparation of teachers to deliver high-quality education for achieving SDGs in Qatar. To this end, this study investigated teachers’ development needs, including their professional preparation, empowerment, and assessment, by employing semi-structured interviews in selected schools. In summary, the findings show a lack of professional development (PD) opportunities, and the current PD approaches have no direction, purpose, or progress. The results also demonstrate that objective and customized assessment methods, a clear and robust career roadmap, and career promotions accordingly would increase teachers’ motivation for their, and thus students’, development. In addition, only a few teachers are aware of the SDGs and their connections with education. Therefore, there is a need to raise their level of understanding and motivation by preparing them with the right set of skills and tools and paying attention to the teachers’ development as a whole at school, society, and policy levels.

1. Introduction

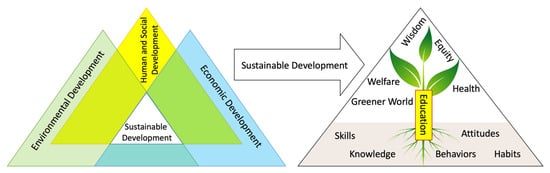

Sustainable development has been a global paradigm demanding radical changes in economic, social, and environmental development trajectories across national and international institutions since the onset of the undesired effects and irreversible calamities of the industrialization era during the 20th century. Qatar has integrated sustainable development into its national vision [1] to achieve balanced development between economic, environmental, social, and human dimensions and between the present and future generations [2]. To this end, Qatar National Vision (QNV) envisions a diversified and innovation-driven knowledge-based economic development with less dependency on its oil/gas resources and more on its human resources by 2030. Therefore, education systems have been at the core of SDGs and national visions. Education ensures the growth and development of the next generations (human resources) with the right set of knowledge, skills, behaviors, and tools. In addition, these features enable humankind to comprehend and meet the intertwined goals of sustainability such as curbing global warming, increasing welfare, providing a greener world, and achieving equity in all aspects (economy, gender, and so on) (see Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1.

Desired sustainable future approach.

Education systems are comprised of visions, strategies, institutions, policies, and written and unwritten conventions and have a broad range of stakeholders, including students, teachers, parents, decision makers, businesses, and industry circles [4]. Education systems and their outcomes vary from country to country depending on history, tradition, culture, geography, national visions, economic and demographic structure, governance, policy, and leadership, among many other factors. As education is a critical factor of sustainability, teachers’ development and status are considered one of the most critical factors within the education system, among others such as parents, school, environment, curriculum, and performance assessments [5]. The quality of teachers directly affects the overall quality of student achievements in social, ethical, and moral dimensions and the education system [6,7]. The main reason for teachers’ impact on the outcomes of the education system is that they are the main contact, delivery, and reflection points with the subject of the entire education system: students. Therefore, any changes in teachers’ development, including their education, training, recruitment, retention, performance assessment, and promotion, directly affect the education goals and education system and, eventually, the SDGs at the national level.

Qatar recognizes teachers’ role in achieving its ambitious QNV 2030 targets because they not only educate and train the next generation but also motivate them to follow the nation’s vision. However, the recent underachievement levels of students in international and national assessments show that Qatar has a problem in the education system and hence teachers’ motivation, skills, or abilities. In this regard, the Qatari government has identified as one of the challenges that there is a substantially limited number of Qatari teachers, and thereby around 95% of teachers are non-Qataris from various parts of the world but mainly from other Arabic-speaking countries in the Middle East [8]. Although the government has diligently embraced this diversity, achieving sustainable education and hence SDGs with a considerably large teaching force with varying qualities, backgrounds, and professional and social aspirations is a significant challenge. We investigated this challenge and potential solutions from the teachers’ development perspective by considering recruitment, assessment, re-training, and development of teachers [9].

This preliminary research—part of a larger long-term project that has been approved and supported by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MoEHE)—had two objectives. The first was to understand teachers’ professional development problems and misalignments in Qatar through the lens of a system involving a multitude of stakeholders. The second objective was to propose a progressive and tailored set of recommendations for teachers’ developmental needs grounded in systems and design thinking. To this end, a comprehensive literature review and semi-structured interviews were conducted to obtain an in-depth understanding and provide insights into teachers’ experiences and desires. In this inductive reasoning research, we conducted interviews with mainly teachers, administrators, parents, and the MoEHE representatives for an in-depth contextual understanding of teachers’ development experiences, along with problems and future desires.

2. Literature Review

The teaching profession is a complex and multidimensional process that, if not well addressed, will cause education outcomes to miss their targets. Therefore, this process requires a deep and multifaceted understanding to synthesize and integrate a proper set of knowledge to serve different situations in varying conditions with diverse groups and unique individuals.

In the decade between 1980 and 1990, there was increasing concern directed at the state of education in the United States. Reports such as A Place Called School [10], A Nation at Risk [11], High School: A Report on Secondary Education in America [12], Horace’s Compromise: The Dilemma of the American High School [13], and Action for Excellence [14] documented the state of the country’s education system during that period. As Wilcox (1995) said, “All these articles had a theme in common: an indictment of the American education system and its failure to provide quality education for its students” [15]. These reports brought a revolution in the education sector. For the first time in the US history, the focus was on the education system, and a massive reform took place. There were extended school years, extended school time, and a thorough review of the courses being provided [16]. Additionally, school administration was reformed through leadership training, more careful selection of teachers, and regular teacher evaluations. It had become evident that the foundation of the teachers and administration mattered and that if it was not fixed, all reform efforts would be fruitless. In his book, In the Name of Excellence, Toch (1991) said, “if the problems in teaching were not addressed, the reform movement would grind to a dead halt” [17].

Griffith and Conrad (2008) described the “knowing-doing gap” problem that most teachers—especially those who have faced repeated reforms within their education systems—believe that national initiatives are substantially transient and thus difficult to embrace [18]. Therefore, educational reforms should be designed professionally together with the participation of all stakeholders and should be persistent and robust for a long time. Furthermore, the literature indicated that teachers’ engagement problem with nations’ educational strategy mainly originates in inconsistency between expectations and reality, mainly due to their incomplete and/or incorrect professional development (PD) strategies [18]. In this regard, policymakers should develop an attractive complete set of PD strategies and apply them consistently with the published guidelines to avoid any gaps between expectations and reality.

Globally, there are promising and successful examples in applying robust PD strategies such as Finland. Niemi (2015) highlighted the three-phase model adopted in Finland, which includes initial teacher education, orientation (otherwise known as induction) in the first five years into the profession after graduation, and in-service teacher education [19]. Through this model, the career-long development for the teachers continues until they retire. This ensures that teachers remain effective, efficient, and knowledgeable in the classroom. Many scholars support this “teacher development continuum”. Schwille and Dembélé (2007) argued that there is a need for a comprehensive framework that can be used to organize and understand how teachers obtain and deliver knowledge and improve the style they teach it in [20]. Additionally, Feiman-Nemser (2001) supported this continuous development and emphasized that teachers’ schooling has an impact on who they are as teachers [21].

2.1. Education System in Qatar

Qatar is facing a new era of development in which many different fields are seeking to pursue sustainable pathways of development to correspond to urgent global demands. Like other countries in the region, Qatar aims to transform its oil/gas-based economy into a more diversified knowledge-based economy [22]. A knowledge-based economy, as defined in the QNV, is about facing international competitiveness with innovation [23], entrepreneurship [24], excellence [17] in education, a world-class infrastructural backbone [25], an efficient delivery of public services [26], a transparent and accountable government [27], and environmental awareness such as achieving the zero-waste concept [28]. Among these requirements, Qatar has recognized that education is the critical component in achieving the target of building this knowledge. Porter (1990b) likewise suggested that the knowledge capacity of a nation needs to be developed through well-investigated strategies that consider interactions of social and human capitals with their institutional regimes [29]. Therefore, adopting legitimate policies and regimes will aid the human and social development processes. In alignment with this, Qatar has invested a significant amount into the education system; however, the system is not meeting or achieving the expected outcomes. This has been measured in the outcomes of students in international examinations, along with annual reports of the students’ examinations in schools, both of which prove the instability of the education system as a whole. As a result, Qatar has introduced several reforms to its education system in the past two decades, but due to the lack of detailed implementations of these reforms, the whole system has been weakened, resulting in unexpected outcomes [30].

2.1.1. A Brief Educational History of Qatar

Schools in Qatar were initially established in the 1950s and were segregated by gender. Girls who graduated from these schools would go back home to be housewives or would go on to be teachers and administrators in the girls’ schools. In comparison, boys would explore other disciplines such as ministry, military, and family businesses and trades. By the 1990s, slightly before the Qatari grand education system reform, most schools’ operators (i.e., administrators and teachers) were nationals, especially in the girls’ schools [8]. In 2001, a comprehensive and diligent assessment of the K-12 education showed that the education system was underperforming because of dependency on rote learning, unattractive curriculum, and limited student–teacher interaction [30]. In addition, as a profession, teachers were not receiving a desired social status and were receiving considerably low salaries and inadequate professional development. Regarding the infrastructure, classrooms were overcrowded, and schools were unsatisfactory [31].

In 2002, after recognizing the shortages in the education system, Qatar began a new reform campaign, Education for a New Era (EFNE), that emphasizes student-centric education and pedagogy [32]. To this end, a new organizational structure—the Supreme Education Council—school models, and new curriculums were introduced for a high-quality education that reflects the aspiration to build a sustainable future [33,34]. In the EFNE reform, students were required to be active and self-responsible learners and teachers to act as guides and facilitators for knowledge seekers instead of only transmitting knowledge (Brewer et al., 2007). Furthermore, teachers became flexible in developing their custom instructional designs with proper tools to promote questioning, exploration, and critical thinking. However, Ellili-Cherif and Romanowski (2013) reported that principals, teachers, and parents indicated difficulties about extra work and effort, sudden and frequent reforms, and threats to the local culture and language [33]. In another study, Romanowski et al. (2013) reported that principals, teachers, and parents stated their negative experiences with the EFNE reform: the lack of parental involvement, student motivation, and teacher qualifications [35]. In 2016, the Qatari government took another step to improve the educational system, and after abolishing the Supreme Education Council, it performed a structural change by establishing the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MoEHE). The ministry is assigned to deal with all aspects of education in Qatar.

2.1.2. Teachers’ Professional Development and Role in Qatar Educational System

Professional development—including preparations, assessment, and promotions—and status in society for teachers are critical factors in pursuing any educational reform [5]. Motivated and well-equipped teachers will provide high-quality education, and this will lead to accomplishing sustainable development goals. In this regard, the Qatari government has been striving to improve these factors since the educational reform, Education for a New Era, was implemented. Subjects such as mathematics and sciences, in this reform, were facing a transition in the instructional language from Arabic to English which demanded a lot of effort significantly from both students and teachers to adopt this requirement. As claimed by Nasser (2017), out of many transitions, this had the most significant impact on the teachers, mainly from other Arabic-speaking countries in the Middle East, as they felt unqualified to be employed in the new independent schools in Qatar [36]. Due to this transformation in the system’s structure and the need to satisfy the expected qualifications, many national teachers and administrators dropped out of the system, comprising a group that went on to be called the Central Provision. Independent schools began to look for a multi-national teaching workforce of professionals who could fill those gaps.

Diversification of the teaching workforce produced complex demands regarding teachers’ development. Multi-national teachers have affected the context of the educational system since no clear training or pathways were established for them, and they have functioned in the system without having the right background. Until today, foreign teachers have not had the right set of training to enable them to teach in public schools, and this reflected critically on the outcomes of the system. Regarding the teachers’ backgrounds, the College of Education in Qatar University previously offered bachelor’s degrees in general education, which is where, prior to 2000, most teachers used to receive their degrees and training from, until the reform took place, and this program was closed. In response to the reform, degrees became more specialized in the fields of study, and pedagogical courses were provided out of the college [36]. Furthermore, it was requested that teachers become licensed to ensure their professional attainment levels were adequate, which added a lot of stress on the teachers. Policies for teachers were coming from different government offices, which, unfortunately, caused mistrust in the teachers’ ability and diminished their empowerment, opposing the initial reform strategy that encouraged autonomy. A final cause was the intensive work demands placed on teachers, including after-school working hours, PD requirements, and continual strategy updates and changes.

Qatar’s teaching competency lags behind other countries in developing human skills, leading to a dependency on expatriates for domestic production. Thus, the literature review indicates a noticeable gap in identifying and localizing teachers’ effective recruiting, retaining, and professional development approaches to enhance teaching competency from a holistic system perspective.

3. Methodology

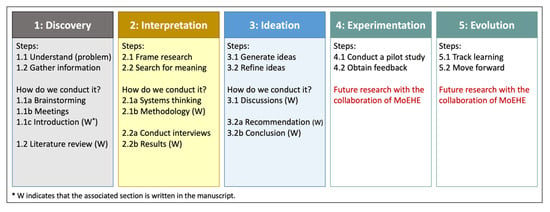

This study was structured according to a design thinking methodology. Design thinking, as an implicit activity in the designing process, is a dynamic practice to view, shape, and construct better understanding within the process of solving a problem in order to come up with the hidden problems and issues to finally work creatively and synthetically on building upon ultimate solutions [37]. In this regard, we followed five structured phases of design thinking—discovery, interpretation, ideation, experimentation, and evolution phases—to interpret observations into feasible and successful solutions (see Figure 2) [38]. The first phase is to understand the problems in the education system by performing brainstorming and meetings within the research group and stakeholders and gathering the related information through a literature review. The outputs of the discovery phase are the introduction and literature review sections in this manuscript.

Figure 2.

Design thinking process followed by this study.

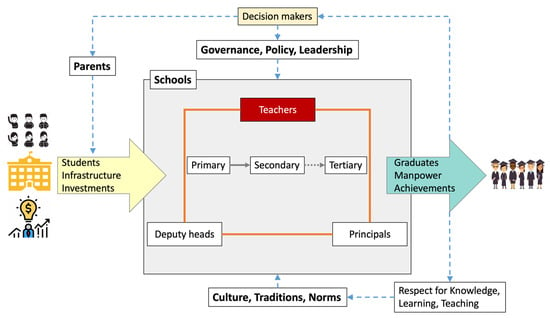

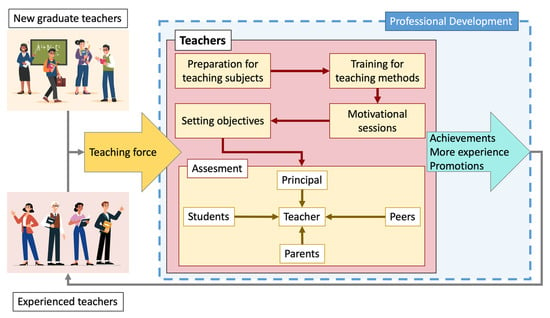

Second, in the interpretation phase, we employed systems thinking approach to depict a holistic educational system that enables us to realize all the stakeholders and operational mechanisms (see Figure 3). In this holistic system, we framed our research perspective with teachers and their professional development and drew a diagram of systems thinking for teachers as well by emphasizing teachers’ preparation, training, motivation, objectives, and promotions under the professional development (see Figure 4). In addition to systems thinking diagrams for the educational system and teachers’ development, we also integrated teachers’ PD to the ultimate target of achieving sustainable development goals (see Figure 5). The next step in the interpretation phase was to develop interview questionnaires according to the systems diagrams and conduct semi-structured interviews to better identify missing points of the problem and potential solutions. In this stage, the methodology and results sections are written into the manuscript. Third, in the ideation phase, we refined all the information gathered throughout this study by discussing the results and then generated ideas for potential solutions by making short- and long-term recommendations. As a result of this phase, we wrote discussions, recommendations, and conclusion sections of the study.

Figure 3.

A holistic education system utilizing systems thinking approach.

Figure 4.

Teachers’ professional development diagram employing systems thinking.

Figure 5.

Teachers’ professional development paves the way for sustainable development.

The remaining two phases—experimentation and evolution—require heavy and long procedures and permission from the MoEHE. Therefore, we completed our study after conducting the ideation phase with recommendations and assigned the last two phases as future work with the collaboration of the MoEHE. The fourth phase, experimentation, is a pilot study and flexible process as it allows developers to try new ideas and go back and forth within the process in case something needs improvement. In the fifth phase, project owners who implement the pilot study will track the teachers’ performance with respect to the proposed recommendations and move forward.

3.1. Systems Thinking: A Holistic Educational System and Teacher’s Professional Development

For education systems, it is essential to fully adopt the system thinking approach since many subsystems play a role in shaping it. In a study conducted by Waddell (2005), relations and scales interacting with multidimensional systems were described as a change in an extensive system depending on the association within stakeholders [39]. In education, students and teachers are the primary stakeholders, and parents, policymakers, and close surroundings are secondary stakeholders (see Figure 3). Then the social surroundings, infrastructures, and other factors affect the education system but after primary and secondary stakeholders. Each parameter here acts as a system on its own and is inter-linked to others through a flow within this complex system. In this regard, we focused on teachers in a holistic educational system and drew a teachers’ professional development diagram by utilizing system thinking (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 shows the preparation for subjects, training for instructional methods, motivational training, setting objectives, assessments, promotions, and satisfactions (i.e., achievements) under the umbrella of teachers’ professional development. It completes the current cycle and moves forward to the next cycle of professional development. We developed the interview questions in meetings and brainstorming sessions—involving educational professionals, the research group, and other stakeholders—according to the systems thinking methodology depicted in Figure 4. Furthermore, this study integrated teachers’ professional development with achieving sustainable development goals (see Figure 5). Motivated and well-equipped teachers will provide high-quality education, and this will lead to accomplishing sustainable development goals.

3.2. Interviews

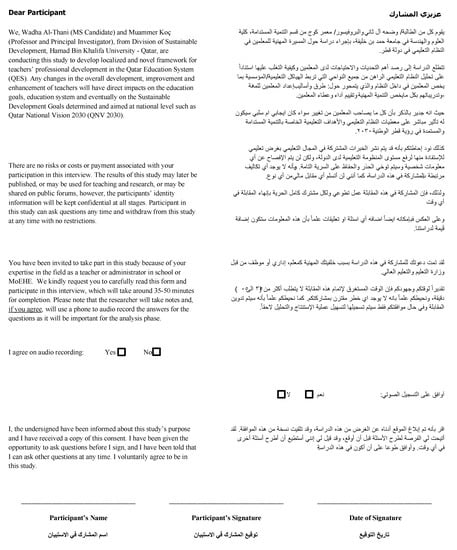

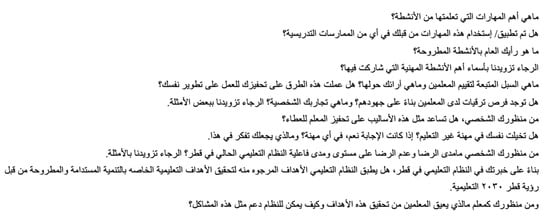

This study developed semi-structured interviews on teachers’ professional development according to the systems thinking approach described in the previous sub-section (see Appendix B for the interview questions). The interviews were conducted with teachers for an in-depth contextual understanding of their experiences, desires, and career journeys in Qatar. The interviews were conducted carefully to ensure that reliable data were collected and that the interviewees did not go out of the scope of the research, thus active listening and nonjudgmental behavior were two essential practices adopted by the interviewer [40]. Teachers’ professional journeys informed the development of questions asked in the interview sessions within the school setting, which touched on the following topics: (1) the preparation stage, (2) PD, (3) evaluations, (4) promotions/incentives, and (5) their general knowledge and awareness about the SDGs and QNV 2030.

The clearance permission from the MoEHE was obtained after presenting the main objectives, methodologies, and interview questions. Then, the Institutional Review Board of Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar accepted this study’s interview application which was required because it involved interactions with humans. The semi-structured interviews were recorded on audiotapes at a convenient time that suited the teachers’ schedule. They were performed in a meeting room of the schools, and each lasted for approximately 30 min. The interviews were conducted by the first author of this study trained in conducting semi-structured interviews. Before conducting the interviews, a consent (see Appendix A) form was outlined for all potential interviewees to obtain willing participants in this study. The form included an overview of the study and its main objectives, potential risks, benefits, explicit request to audio-record the interview, and finally, the contact information of the interviewer and the supervisor of this study. Moreover, the form and the interview questions were written in both Arabic and English languages to suit the comfort of the interviewee and are presented in Appendix B. The audio-recording helped the interviewer obtain reliable data without being biased to a particular direction. If the interviewee disagreed, a second note-taker was available to support the reliability of all collected data. The interviews were all confidential, and the gathered data were transcribed in a notebook only used for this purpose by the researcher solely.

After each interview, the responses were typed and saved anonymously in a protected folder, ensuring no personal information was declared other than the school affiliation and general background information. Member checking is an essential practice used to verify and validate their answers [41]. Therefore, to validate the collected data, all scripts were shared with the corresponding interviewees to obtain their approval. After the validation, the manual analysis was used to assist data interpretation and coding. Creswell (2013) and Kvale (1996) both suggested that analyzing qualitative data means dealing with dense and rich texts and transforming those texts into a smaller number of meaningful themes and patterns [42,43]. Therefore, qualitative research encompasses a continuous interplay between data collection and analysis [44].

3.2.1. Sampling and Participant Selection

According to Creswell (2007), selecting appropriate candidates for interviews plays a critical role in the overall findings of the study [45]. In this regard, four public schools were chosen based on the selection criteria discussed as follows. First, the level of schooling that was chosen to serve this study was preparatory level due to several reasons. The preparatory level is a level where students face enormous challenges. As addressed by Roeser, Eccles, and Sameroff (2000), a substantial portion of students in middle grades possess negative attitudes toward certain subjects, engage in behavioral misconduct, and face decreased motivation [46]. Second, two of the selected schools were categorized as high-performing (HP) and the others were low-performing (LP) schools for both boys and girls according to the schools’ success levels in the national examination. These results are shared by the MoEHE through their official website, and under each school, there is its annual School Resort Card (SRC). Third, the selection of the schools had to be in Doha city to satisfy the criteria of having a representative mix of the population besides being un-prejudiced for a specific tribe. This is because the Planning and Statistic Authority in Qatar reports that Doha city has the largest and most mixed population among other cities around it [47]. Finally, the student-to-teacher ratio was also taken into account where all preferred schools did satisfy it to be around 11:1 which competes with the world benchmarks.

3.2.2. Demographics

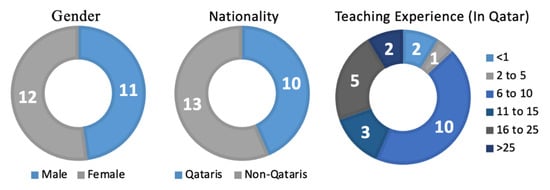

The selection of teachers was based on “purposeful selection,” described by Maxwell (2006) as, “a strategy in which particular settings, persons, or events are deliberately selected for the important information they can provide that cannot be gotten as well from other choices” [48]. This study attempted to select teachers with various teaching experience, nationalities, and subject matter expertise to explore the diverse challenges faced by the teachers in the education system in Qatar. The chosen teachers were nominated by the principal and the deputy head of academics (DHA). Five to six teachers from each school were interviewed, with a total of 23 teachers, including 12 female and 11 male teachers (Figure 6). Their attributes such as experience, nationalities, social status, and teaching subjects are represented in Figure 6 (see Table A1 in Appendix C for teachers’ details). The distribution of nationalities and gender was important for representing unbiased data. Similarly, their years of experience helped in comparing their preparation, development, and status. To supplement the teachers’ responses, an administrator and two parents from each school were also interviewed. Furthermore, representatives from different MoEHE departments—the Training and Educational Development Center, Educational Supervision Department, Office of Teachers Affairs, and Office of Human Resources—were interviewed to understand the reasons behind their actions and decisions in order to look at the situation from multiple perspectives.

Figure 6.

Characteristics of the teachers.

3.2.3. Data Analysis

This research followed Creswell’s (2009) six steps for data analysis: (1) organizing and preparing the data, (2) reading through the data to become familiarized with it, (3) performing detailed analysis using coding for categorized segments, (4) generalizing those codes into small categories or themes, (5) identifying the emergence of themes that share similar sentiments, and (6) interpreting the data [49]. There was an attempt to utilize software to ease the process of analyzing the data. However, no software was found to support data in Arabic or the context of Qatar, and thus most meaning would have been lost through software-based analysis. As the last step to avoid losing any meaning or information mentioned by the interviewees, the data were translated into English as carefully as possible.

3.2.4. Validation and Trustworthiness

Qualitative research requires the researcher to have an active role in collecting and interpreting the words and expressions of others. Stake (1995) cautioned that, in this kind of research design, the researcher should be open-minded and understand the research as the participants do instead of imposing their assumptions [41]. Therefore, as recommended by qualitative researchers, certain steps were taken to avoid risks to credibility and trustworthiness: (1) Information was gathered from multiple sources: in this case, teachers, administrators, parents, and MoEHE representatives. In this field, the process of gathering information from multiple data sources is called data triangulation [50,51]. (2) Member checks were performed by sending each participant a copy of their transcript and asking them to verify the data within it [50]. (3) Finally, the study was peer-reviewed by its supervisor and co-supervisor to increase the dependability of the research or consistency of the findings.

4. Results and Discussion

To represent the results of all interviews, thematic analysis was performed by coding the data to identify patterns.

4.1. Findings and Trends from the Conducted Interviews

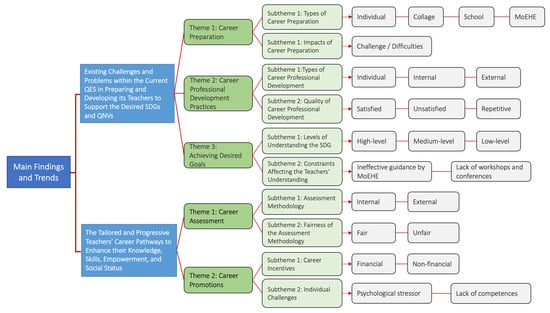

The key findings from all stakeholder interviews are analyzed, and trends are identified to show a holistic picture of teachers’ professional development and career journeys. The interview questions did not reflect the research questions directly; rather, the research questions were formulated into several interview questions to ease the flow of the interviews and facilitate a thorough understanding of the research objectives. Figure 7 illustrates the relationships between the research questions, interviews, and findings to ease the reading process of this section. Since this section includes descriptive data and discussions, the analysis was divided into two parts for each research question. Then, themes were established based on the research needs to serve the study’s main objectives. Regarding the educational professionals’ and teachers’ feedback, subthemes were established to complement the themes and subthemes, and patterns were configured to achieve the overall target of this project.

Figure 7.

Interrelations between research questions, central themes in interviews, and findings.

4.2. Research Question 1: Current Challenges for Teachers within the Qatar Education System (QES)

The findings in this subsection corresponding to the research question of “What are the challenges and problems of the current education system in Qatar in preparing and developing its teachers to support the SDGs and QNV?” were grouped into three main themes: (1) career preparation; (2) professional development practices; and (3) achieving desired goals. Each theme was further divided into subthemes and then categorized by participants’ perceptions of and experience with teaching. The following sections explain these themes in detail as obtained from the interview analyses.

4.2.1. Theme 1.1: Career Preparation

This theme emerged throughout the interviews, and two subthemes were determined as: (i) types of career preparation and (ii) its impact on their career journeys.

Subtheme 1.1.1: The types of career preparation. This subtheme focuses on the levels of preparation that were identified through the interviewees’ responses, including individual, university/college education, school (workplace), or ministry (MoEHE) levels, as these were the primary sources of preparation for the teachers’ careers.

For the individual preparations among the 23 teachers, six teachers shared similar claims of participating in self-supported further reading, attending external workshops, or learning from their surroundings. Two of these—Qatari female teachers—reported that they needed extra preparation, and thus they attended some external workshops to support their knowledge and skills in dealing with students, and this was performed in the summer before the beginning of the academic year. In contrast, the other four (non-Qatari) teachers reflected that they prepared themselves through reading or with help from their families, as some of their family members were teachers or serving in the educational field.

For the college preparations, thirteen of the teachers discussed being prepared during their studies and agreed on their satisfaction, to a certain extent, with this preparation phase. The Qatari and non-Qatari teachers who graduated from the College of Education in Qatar University agreed that their studies and curriculum at the university prepared them very well for fieldwork. Since their program obligated them to attend a semester in a school (i.e., internship), undergraduate students (i.e., teacher candidates) had the chance to act as assistants to teachers in their departments where they helped in preparing the lessons, attended the lessons, examined the way teachers prepared and evaluated the assessments, and, most importantly, learned how to implement all the theoretical knowledge they gained in the university in real-life practice. Furthermore, they were also evaluated on their work.

On the other hand, all teachers with university education from other countries lacked the strategy implementation skills that the QES highly focuses on. In their countries—for example, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Sudan—universities emphasized the subject matter and usually made room for teachers’ creativity in teaching. The teachers recounted their struggles at the beginning of their journeys in Qatar as they were restricted from implementing those strategies, which was a challenge until they spent effort and time to read, learn, and ask about the way of teaching in the QES.

For the school preparations, thirteen teachers shared their interpretations. There were two different approaches implemented for new teachers in the schools. The first one, which is no longer implemented, was during the decentralized era (2002–2014) of the Supreme Education Council. During that period, specialized teams were assigned to each school to prepare and monitor teachers. Teachers faced many difficulties as almost everything was changed, including the curriculum, language of teaching, way of teaching, school structure, and other aspects of the education system.

On the other hand, with the reinstallation of the centralized structure that has been ongoing from 2014 to the present, schools are responsible for managing the adaptation, orientation, and re-training of new teachers. Accordingly, the deputy head of academics and coordinator teachers of each department (i.e., science, math, language, etc.) prepare plans for new teachers to enable them to be slowly introduced to the fieldwork. The plans differ from school to school and are flexible based on the preference of each coordinator. There are neither guidelines nor restrictions for these plans set by the MoEHE.

The MoEHE provides teachers with pre-career training in a one-week workshop before they start their official fieldwork. This weeklong preparation includes teaching strategies, grading criteria, skills for managing classrooms and student behavior, etc. The workshop is open to all new teachers coming from Qatar or other countries. The teachers interviewed had different opinions about this weeklong preparation session. Some said it was enough and comprehensive in discussing all the necessary standards, while some mentioned it should have been different for teachers from Qatar compared to teachers from other countries. Others believed that it lacked topics regarding the culture of students and schools in general as the schools have mixed student bodies. Another point was made regarding the practice of hiring new teachers to teach grade 7; teachers mentioned that this was a difficult level not only because students transition from one level to another (i.e., primary to preparatory) but also because they experience physical and emotional changes that usually influence their behaviors as they transition to acting like teenagers.

Another kind of official preparation approved by the MoEHE is the preparation of candidates in the Teach for Qatar (TFQ) institution. This entity is another source that provides the QES with trained, qualified, and experienced teachers. It has a different approach, as they hire candidates who are interested in teaching but have not graduated from a college of education or received a diploma in education. TFQ trains candidates with all the necessary requirements and prepares them to teach.

Subtheme 1.1.2: Impacts of Career Preparation. Despite its many levels, if preparation is not carried out in the right way, teachers’ quality of performance and delivery will be impacted, ultimately affecting the whole QES. Furthermore, teachers experience some difficulties and challenges through their first period in teaching. Career preparation with clear guidelines has a significant impact on mitigating these difficulties and challenges. In this regard, one of the teachers (HP-G-2) expressed: “I lacked a lot of preparation. I had some fear and many challenges from my career at the beginning, but I did not have any other options. However, my coordinator had a great and positive role in overcoming this”.

Other stakeholders who had views regarding this topic were school principals, DHAs, and MoEHE representatives. The schools’ principals and DHA members who were interviewed had two counterviews regarding teachers’ preparation. Some stated that it is the MoEHE’s responsibility and that clear guidelines should be established for those teachers, since schools are already overloaded with different responsibilities, especially at the beginning of the academic year as they welcome new students, parents, and teachers. Consequently, a clear framework and guidelines will guide the DHA members and coordinators on how to manage new teachers, and the teaching and other administrative loads on the new teachers should be reduced. The MoEHE treats new teachers the same as existing teachers in terms of their teaching load (i.e., number of classes taught per week) and other responsibilities and expectations.

Nevertheless, a DHA reflected that they had clear guidelines agreed upon between them and the coordinators to manage the new teachers in a way that eases the process for all parties. Their guidelines detail the process of involving the teachers slowly in the fieldwork with constant monitoring until their readiness is ensured. The MoEHE members discussed that they were working on this issue and restructuring the preparation stage for teachers. Moreover, they emphasized that the coordinators at the school level were now given a lighter load for handling such situations. In general, the MoEHE, along with the schools’ DHA members and coordinators, should agree on guidelines and a framework for new teachers regarding the preparation process. Thus, generating a unified guideline to present to all new teachers in all public schools, and explaining it in detail, would facilitate the induction process and would avoid overloading new teachers with an excessive and more complicated administrative load. The complexity of the school contexts and student body in Qatar must be adequately managed to prevent new teachers from struggling and leaving the profession.

4.2.2. Theme 1.2: Career Professional Development Practices

To obtain information on teachers’ PD practices, teachers were asked three different questions to allow the interviewer to obtain a full picture regarding their PD. Responses from the participants encompassed various interpretations. However, some responses overlapped, and subthemes were thus shaped to review all the participants’ elaborations on this topic: (i) types, (ii) quality, and (iii) impact of PD on teachers.

Subtheme 1.2.1: The types of career PD. According to the findings, PD practices can be divided into (i) individual effort, internally within the school, and (ii) externally by the MoEHE or College of Education at Qatar University (QUEC).

For individual PD, two Qatari female teachers (HP-G-2 and LP-G-6) talked about external workshops that they attended and benefitted and gained skills from. The pattern involves external workshops that did not fall under the MoEHE supervision, which meant an extra burden on teachers. One of them (HP-G-2) elaborated:

However, for me, I always search for external workshops. I recently registered for an online workshop on how teachers can make a short movie on the presented lesson, which I applied in one of the lessons, and it reflected positively in the classroom. Thus, it eager me to present something different and not be restricted with the strategies by the MoEHE.(HP-G-2)

Considering internal PD, almost all teachers contributed by describing their experiences in various workshops. In general, internal workshops are proposed by each coordinator based on the needs of their department, and another option is proposed by the DHA who lists the general needs of teachers and coordinators based on the upcoming year’s goals and objectives. These workshops are then raised to the MoEHE for their final approval. Therefore, internal PD is dependent on the schools’ policies and guidelines and, ultimately, on the approval of the MoEHE. The interviewees’ opinions advanced a different level of satisfaction with such internal workshops. Female teachers, in both high- and low-performing schools, recalled mentioning their abilities to prepare and deliver workshops, but their schools did not support such opportunities. Principals, DHA members, and coordinators are the only sources of delivering internal PD in their schools. One of the teachers (LP-G-5) stated that “some of the workshops are very helpful, and some are not, in my opinion, depending on the lecturer and fulfilling the number of Professional Development courses per semester”.

The male teachers, in both high and low-performing schools, highlighted their opportunities in presenting workshops, thereby sharing their experiences and best practices with their colleagues within the school. If a teacher introduced a new strategy or technique, and the coordinator or the DHA thought it would benefit the students, the DHA or coordinator asked the teacher to prepare a workshop and present it to the other teachers. In this regard, one of the teachers (LP-B-2) stated that “in our school, we hold distinctive practices program, which is an internal policy adopted by the DHA, in which experiences among teachers are transferred through workshop sessions”.

Others elaborated on the reputation of the workshops, detailing their focus on particular topics and the inconsistency in their levels. Teachers from all schools commented on this aspect. For instance, HP-B-2 stated his concern regarding the reputation of the workshops: “For me, I did not attend a workshop this year because I attended all the workshops, and they are considered repetitive”.

External PD is considered to be an effective instrument in terms of developing teachers in many ways and distributing knowledge among all teachers. However, the teachers in the QES have been highly disappointed with this type of PD and raised many concerns. External PD opportunities are not managed well by the MoEHE; therefore, a call for support was elevated by higher management to QUED’s center for PD practices to fill this gap. This center is responsible for providing teachers with workshops and teaching licenses based on the needs communicated to them by the MoEHE. Another major event is the annual education conference organized by the MoEHE.

HP-B-5 said that attendance at external workshops was not considered in their annual evaluations, which suppressed the teachers’ motivation to attend workshops as they waste their time.

The courses are repetitive, such as national exams preparation which is repeated every year with the same content...In my own opinion, external professional development has a positive impact, such as attendance of workshops in other schools or live classrooms in other schools.

Subtheme 1.2.2: The quality of PD. Teachers shared their feedback regarding the quality of PD practices. Their feedback was categorized into three subthemes according to the quality of the PD provided: (i) satisfied, (ii) dissatisfied, and (iii) repetitive.

Teachers conveyed their satisfaction with some PD opportunities concerning training for teaching abilities that focus on the implementation of technologies and classroom management and strategies. Nine teachers interpreted the vast benefits gained through this PD. Some others seemed to be satisfied but still looking for further opportunities through which to improve and fulfill their needs. HP-G-1 described her satisfaction: “the workshops are effective and valuable as they are dynamic and fixable to the other changes that we face frequently. Thus, those workshops are up to date”.

On the other hand, when it comes to the subject matter of PD, conferences, or negotiations that are related to the curriculums and subject fields, teachers exhibited their dissatisfaction and urgent desires for such opportunities where they can share and discuss the recent studies, techniques, and skills regarding these topics. The chances to attend some external workshops, discussions, and conferences within the academic year for teachers exist in the QES but sparingly. The only conference that all teachers in the QES are eligible to attend annually is the Education Conference by the MoEHE. This event aims to deliberate on challenges and opportunities and propose practical solutions and innovations within the education field [52]. Other conferences, such as those arranged by QUEC, usually conflict with teachers’ schedules; therefore, only a few can attend. Another well-known event is the WISE Conference, which occurs every other year and provides an excellent opportunity for teachers to explore a broader image of education around the world. The WISE is an international, multi-sectoral platform for creative thinking, debate, and purposeful action for new approaches in education involving educators from all around the world. The main issue with this event is the language barrier; although translation devices are provided, attendance and engagement are not popular among the teachers as the conference is conducted using English as its main language.

Despite all available opportunities, the teachers stated their dissatisfaction with the scope, quality, and timeliness of those events as well as the covered subject matter. Teachers, wanting to contribute to their students’ learning, are curious and always wanting to learn more productive and valuable knowledge and skills beyond the skills that the MoEHE asks the schools to focus on in their internal PD. Moreover, teachers do not have any influence or representation when it comes to changes, improvements, or reforms of the curriculum, except when they are asked to share their opinions. However, many have never felt that their input was taken into consideration at further levels.

Experienced teachers further complained about the repetition of the workshop over the years, which negatively affects their motivation to participate in PD. Teachers would like to have leadership roles where they can facilitate and share their experiences by presenting in workshops in different ways and with new and refreshing topics. LP-G-4 highlighted this point:

The workshops are very beneficial, and I enjoy them very much. However, they don’t change from one year to another as they always deal with the same topic. For the more experienced teachers, the workshops are boring and repetitive. I think that in this stage, an experienced teacher can prepare and offer workshops instead of attending them, except if there is something new.

Another approach to improving teachers’ PD is to believe in the importance of sharing knowledge among all educators. As most teachers noted, knowledge sharing is a collective behavior in most schools in which teachers share and transfer the knowledge that was gained through a workshop or other event to other teachers. Based on the teachers’ perspectives, the coordinators hold the pivotal role for either supporting these habits or not, as not all schools have this coordinator support in common. Schools that participate in scientific research tend to highlight the importance of sharing the knowledge for the good of all, recognizing its impact on the whole school.

Studies in Malaysia have indicated that Malaysian society is collectivistic through knowledge sharing, which happens naturally because there is a tendency among citizens to help each other [53]. Therefore, although knowledge sharing occurs in most schools, the way it is implemented is essential, and it should not be limited to the school’s environment if it is to be effective. Teachers should be given more trust to share what they know with other schools and educators. Moreover, they can be part of the research conducted by surrounding institutions to reflect the reality. If given an opportunity, teachers will go beyond their circles by giving more and, most importantly, gaining motivation and empowerment. However, such a culture is not easy to establish, as the fear of making mistakes, receiving negative feedback, and being evaluated on shared knowledge will always keep teachers at the same level.

4.2.3. Theme 1.3: Achieving Desired Goals

Teachers were asked about sustainable development to understand their potential to engage in it, as they are the source from which students will gain knowledge of sustainability. The structure of this theme is slightly different from the earlier themes. In Subtheme 1.3.1, teachers were categorized according to their level of understanding of SDGs. Subtheme 1.3.2 discusses what has kept teachers from gaining sufficient knowledge, material, and training to understand SDGs. Both themes are sequentially addressed as follows.

Subtheme 1.3.1: Levels of understanding of the sustainable development goals. To address this theme, teachers were allowed to talk about their understanding of the SDGs and their importance in assuring the stability of resources for current and future generations. Only teachers who can comprehend the SDGs will be able to produce students who recognize and work on those goals. The teachers’ levels of understanding were divided into high, medium, and low tiers that are explained in more detail in Appendix D (see Table A2). Based on these criteria, each teacher was distributed into a category based on their answers, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Teachers’ classifications.

Subtheme 1.3.2: Constraints that affect teachers’ understanding. After verifying their levels of understanding, teachers were asked whether they had received any introductions to or training regarding the incorporation of sustainable development into their subjects. Their replies were divided into two patterns concerning ineffective guidance by the MoEHE and a lack of workshops for the teachers on this subject.

Development in the state of Qatar is remarkable, multifaceted, and widespread. The MoEHE has sought to reflect this development as well as the SDGs in the national curriculum to ensure that the outcomes of the system can cope with this development and further it. When the curriculum was established, a brief introduction was given to coordinators and subsequently delivered to teachers. The teachers did not have a chance to thoroughly examine the curriculum, as they received it at the beginning of the academic year and had to start teaching it to students. All teachers shared their feedback on how the lack of and ineffective guidance affected them and added a tremendous amount to their workload.

The teachers further mentioned their efforts in studying and researching the topics discussed in the curriculum as they were new and sometimes challenging. HP-B-3 said that “the ministry did not offer anything about the involvement of sustainable development in the syllabuses”. On the other hand, teacher LP-G-6, who recently graduated from a workshop that she attended, did have a chance to discuss and be prepared for the new curriculum by stating that “yes, SDGs along with QNV are developed within the subject materials, and with that, we have to implement the competencies strategies, so I believe students will adapt the understanding of the SDGs through this”. Competencies strategy falls under the development of the various skills of students, including linguistics, mathematics, critical and synthetic thinking, and presentation skills.

The other limitation was a lack of workshops and conferences that discuss this topic and are eligible for teachers to attend. The scope of the provided PD is narrow and is not adequate for training and advancing teachers in sustainable development within the QES. International agencies have highlighted the “priority of the priorities” that teachers should have opportunities for education for sustainable development in their PD. Indeed, the MoEHE should have a framework that covers all aspects of the curriculum to ensure education for sustainable development is covered as well. Furthermore, collaboration between different entities will promise a better future for teachers as clear pathways of responsibilities are recognized.

4.3. Research Question 2: Tailored and Progressive Career Pathways

The findings in this subsection corresponding to the research question of “what would be tailored and progressive teachers’ professional development for their career pathways within the QES to enhance teachers’ knowledge, skills, and empowerments?” were grouped into two main themes: (1) career assessment and (2) career promotion. Each theme was further divided into subthemes.

4.3.1. Theme 2.1: Career Assessment

Teacher evaluation policies and systems based on their students’ learning and success have gained momentum for ensuring teachers’ effectiveness. This has occasionally been used as justification to retain or relieve a teacher. The general concept is that if the skills of the teachers are improved and coupled with supervision, as well as evaluation to ensure that the teacher’s knowledge is up to standard, then one can expect that their students will perform well, achieve success, and become more knowledgeable [54]. This will bring high-quality education that paves the way for achieving the SDGs.

The most prominent way to assess teachers’ performance based on world benchmarks is the 360-degree assessment method, by which teachers are evaluated by many parties and on different aspects of their teaching. The method measures several specific skills and practices including classroom management, strategy implementation, their knowledge and how they deliver it, planning, and some other external practices depending on the schools’ administrators [55]. Two subthemes emerged from the interviews to summarize their thoughts: (i) the assessment methodology and (ii) the fairness of the assessment methodology.

Subtheme 2.1.1: Assessment methodology. Based on the information received from the interviewees, the teachers’ assessment in the QES follows the benchmarks method. Teachers receive overall performance assessments which are meant to help improve their performance throughout the years. There were patterns identified through the interviews that illustrated the assessment methodology. The assessment is mainly performed internally and externally.

The internal assessment is the central part of the teachers’ evaluations in which they are evaluated by the principal, deputy head of academics, and coordinator and self-evaluation. However, there was variation among the answers regarding the average number of visits to each class per semester for conducting the evaluation. The schools follow a systematic way of evaluating the teachers that all teachers agreed to, and the number of visits by the principal and DHA to each class depends on whether the teachers satisfied their requirements. If they did, then one or two visits are common. However, if the teacher has some weaknesses, then the principal and DHA member will visit more frequently until the teacher improves.

After each visit, the evaluator shares their comments with the teacher to help them improve specific requirements or encourage them to keep up their excellence. Teachers highlighted the advantages gained from this assessment system. The boys’ schools encouraged the idea of peer-reviewing each other, and much more authentic feedback was provided, especially to the new teachers. The teachers also felt more relieved as this would not be added to their final evaluation. LP-B-1 mentioned: “I was new to Qatar and my colleagues peer-reviewed me, and this helped me to improve substantially. Their attendance was not frightening as much as the coordinator and principals”.

Other evaluation criteria are administrative, focusing on attendance, community service, within-school activities, and the academic achievements of students. Teachers are supposed to satisfy all the criteria to achieve a good score. School activities and community service vary among the different schools.

The MoEHE performs the external evaluation, which happens once per semester or when it is required. The teachers’ thoughts on this diverge, as they were not sure if the mentors from the MoEHE evaluate them or only attend classes to ensure that the level of the presented lessons is satisfactory. A teacher, HP-G-2, expressed that

External assessment is on external workshops and coexistence in classes as well as community activities outside the school. Assessment from outside the school is usually done by the mentor of Educational Supervision Department of the MoEHE, who give some feedback but to be honest I do not know if it is among the assessment or not.

This shows that teachers are not fully aware of the external evaluation system. When the MoEHE representative was interviewed, she explained, “To date, teachers are evaluated internally and are limited to school administrations”.

Subtheme 2.1.2: The fairness of the assessment methodology. Teachers’ insights on the fairness of the assessment methodology fluctuated, though all teachers agreed that it is a fair methodology evaluating teachers throughout the year, not by a single event. Their concerns were about the evaluators, who were not always capable of understanding the required evaluation criteria. The evaluators—coordinators, DHAs, principals, and mentors from the MoEHE—did not receive any kind of training to be evaluators. Furthermore, in some cases, experience is not enough; principles and guidelines are needed to clarify the overall procedures. Teachers such as HP-B-2 pointed out this gap: “However, the defect is in the person who makes the assessment who should normally have knowledge and awareness of items and standards. Otherwise, he will give a shortcoming or unfair assessment sometimes”. Finally, teachers raised their concerns regarding the number of criteria involved in the assessment form, as they have to cover all the criteria in every lesson all year. This adds a tremendous workload and further limits their autonomy within the classrooms.

In summary, although the performance assessment of teachers competes with the benchmarks, the implementation process is not efficient, and teachers have raised concerns about it. The idea of performance assessment should allow the teachers to showcase their creativity and autonomy, but teachers in the QES lack these specifications. They are constrained within the criteria, as if they miss one item, they will lose points on their final evaluations. If evaluators were trained to evaluate based on the students’ learning as well as any new and creative additions to the lessons, they would add to the teaching process instead of asking teachers to follow strict guidelines. Then, with lifted restrictions, teachers would feel more relief and be able to show more skills and creativity. This would also allow for the integration of competencies between the teachers.

4.3.2. Theme 2.2: Career Promotions and Motivations

Career incentive management systems profoundly impact organizational ability to retain and motivate high potential and efficient employees, resulting in high levels of performance. Once this high level of performance is achieved, teachers’ motivation will be shown through different areas such as empowerment, raising social status, workplace appreciation, and collaborative work among them and with other stakeholders. This section covers two subthemes based on the teachers’ feedback—incentives and individual challenges—which will be discussed consecutively as follows.

Subtheme 2.2.1: Career incentives. All the teachers who participated in this study stressed the importance of having a promotion system available to all teachers. They recognized that despite their increased workloads, their efforts have not been appreciated, especially by other stakeholders outside of the school environment but sometimes even by the school administrators as well. This finding also confirms the study conducted by Ellili-Cherif and Romanowski (2013) [33]. Furthermore, it became apparent that there is a disparity between the national and the non-national teachers based on both financial and non-financial incentives.

Constructing the financial incentives based on the teachers’ feedback, there is a precise regulation that separates the nationals from the non-nationals. The national teachers serving the QES follow the national employee ladder for promotions established by the Ministry of Administrative Development, Labor and Social Affairs as stated by HP-G-1:

We, as Qatari teachers, follow the career progress of the Council of Ministers in the State of Qatar, like the other government bodies. Concerning the career itself, however, we have professional licenses concerning the job title of the teacher that have no financial incentives. However, career promotions are through becoming a section coordinator, then an deputy head of academics, then a principal, and then an educational mentor at the Ministry.

Other kinds of incentives that could be considered monetary are gifts and vouchers that the schools give to teachers. This falls under each of the school’s policies. However, nowadays, the practice has become very limited as the MoEHE has started to interfere with this policy. Therefore, any monetary gifts must first be approved by the ministry. The high-performing school has continued to give gifts from many years ago when it used to serve as a self-operating complex under the Supreme Education Council. This strategy of recognizing the work of teachers was integrated into its system to motivate the teachers to perform better.

On the other hand, non-financial promotions are usually certifications given to teachers and mainly by the schools’ administrators. The MoEHE does not recognize the teachers and does not have any criteria by which the teachers could be recognized. There are some exceptions where teachers are acknowledged, but they are infrequent. Moreover, a promotion can be given as a transfer between schools; for example, a teacher with outstanding performance will receive a letter to be transferred to teach in another level school or a better-performing school.

Subtheme 2.2.2: Individual challenges. Promotions play a critical role for individuals—in this case, teachers—within any organization. All stakeholders around teachers should appreciate and understand their role and encourage them. In the QES, teachers receive other allowances, which differentiates them from others; however, they still believe that it is not enough as it is given to them in certain months during the year. Furthermore, the other allowances only cover the nationals, and the non-Qatari teachers, who are the majority in the QES [36], do not receive any kind of promotion or allowances. Finally, teachers are not paid during the holidays. Therefore, this negatively contributes to a lack of self-confidence and lack of competencies among teachers because the system does not support or encourage them for any desire to build higher competency and self-confidence in their profession. This finding also confirms the research conducted by Romanowski et al. (2013) [35]. All teachers presented a similar pattern of both psychological stressors and lack of competencies.

Psychological stressors were incorporated in almost all teachers’ expressions throughout the interviews. For many reasons, the core stressor for all was a lack of motivation. They expressed their desperations regarding the misalignment and fluctuation of the promotion system. Furthermore, the teachers who had served the system for many years were being treated as the other newer teachers, which was more prominent for the non-Qatari teachers. Teachers also worried about the transferring system. Finally, most teachers are parents as well and require time to follow up with their children’s schools if their children are sick or need extra support, and they should be allowed to use those opportunities. Around seventeen of the teachers mentioned their stress on this subject, while the rest did not present much stress either because they are new to the system or have no children. The first quote, from a female teacher at a low-performing school (HP-G-4), describes the social aspect that causes stress for the teachers:

The female teacher is the weakest cell in this system, which makes us lack motivation for competition, distinctiveness, and development. In the past, we had some hours in which we could go out as we have sons and daughters that we need to follow them up in their schools and who are sometimes sick. In my opinion, there should be more focus on motivating us for work and development. So, they exit the career, and nobody asks why.

The second individual challenge that teachers have faced is a lack of competencies. Teachers lack the motivation to produce efforts and creativity that can be added to the education system as they believe that they are not appreciated at the end of the day. They want to see more tangible appreciation and encouragement to support their competencies. This, in turn, affects not only the teachers but the whole system. The teachers did not explicitly state this point, but in their expressions and feedback on most questions, they reflected their lack of competency and that they remain in their positions for the sake of serving the students and their needs. HP-G-2 pointed out that “Teachers in such cases lack competencies and they will just do the job to achieve the given objective only for the good of students regardless of all other efforts a teacher can give”.

Other stakeholders agreed that such incentives would upgrade the quality of the deliverables from all teachers. They further agreed on the necessity of a clear pathway to teachers’ empowerment to enable them to feel confident and proud of their profession.

The teachers’ expressions in their interviews conveyed disappointment and lost hope. None of the teachers showed passion since they no longer trust the academia or the policy recommendations based on their feedback. They felt that they were the weakest point in the system while, in reality, teachers should be the most reliable link and one of the main focuses of the education system. One of the most effective ways to facilitate this process is through incentives and empowerment. Then, teachers will start to feel they are more appreciated within the system, thus affecting their social status and their recognition within society as well.

5. Conclusions

This research identified that teachers in the QES lack professional development, and this deficiency creates under-qualified teachers and thus an underperforming education system, eventually retarding sustainable development. This study, first, delivered a conceptual holistic educational model by utilizing system thinking; this model proposes a progressive PD roadmap for teachers by employing design thinking methodology. The proposed roadmap is expected to bring success in the education system and thus achievement in reaching the SDGs. The findings show that the professional development vision for teachers in Qatar is misaligned and outdated, and also there is a discrepancy between the current PD guidelines and practices in the education system. The system should be monitored and evaluated by the operational effectiveness and outputs to identify the progress, problems, and gaps. Thus, we expect this monitoring and evaluation, first, to confirm our findings, second, convince policymakers and decision makers, and thus open the doors for improvement. We also presented a system thinking methodology to consider the education system in a holistic approach to enable developing an inclusive system in which all stakeholders participate. Furthermore, this study provided a design thinking approach to developing a tailored education system for Qatar, particularly teachers’ PD, within a systematic methodology rather than implementing ready-to-use systems, which would lead to unexpected consequences.

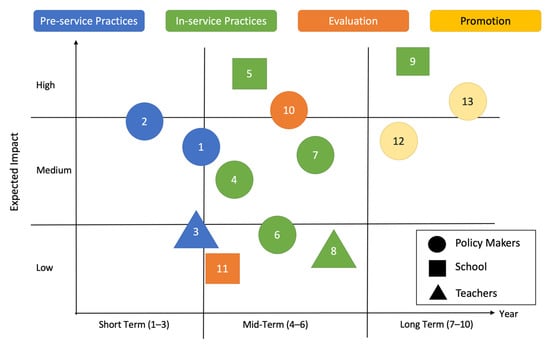

This study followed a design thinking approach consisting of five phases, and three of them were conducted in this research, as explained at the beginning of the methodology section. The last phase in this study was the ideation phase, in which we refined all the information obtained in this study by discussing the results and then generated ideas for potential solutions by making short- and long-term recommendations. We completed our study after conducting the ideation phase with recommendations and assigned the last two phases—experimentation and evolution, explained in the methodology section—as future work with the collaboration of the MoEHE. A list of recommendations based on the findings from the literature review and qualitative research is proposed below. These recommendations based on the findings could allow decision makers to design more detailed and expanded studies:

- Develop and categorize tailored, progressive, and dynamic “career preparation and induction programs” based on teachers’ backgrounds and experience.

- Require all teacher candidates with a degree from non-education-related majors to go through “Teaching/Learning and Pedagogy Programs” either before or during their first semester of teaching.

- During their first year, new teachers should be mentored by an experienced teacher, who can support them in any struggle they might face in any aspect of teaching: coping with students, classroom management, and so on. Their performance should be monitored during their first year to certify them as “fully inducted teachers”.

- Reduce the teaching loads to a maximum of 20–25 h/week to allow teachers to have time to focus on serving the students with their particular and varying needs.

- Extend the autonomy of teachers in the classrooms and in delivering the subject-matter content. This will allow them the flexibility to tailor their teaching methods and strategy implementation to what fits each class and each student’s needs. Implementing this in the right manner will enhance bonding between teachers and students, as students will be their focus rather than the rules and guidance imposed on them.

- Personalize the PD training programs by synchronizing the management among the different institutions under the umbrella of the MoEHE to provide a tailored and progressive set of training to teachers with different skills and knowledge instead of repeating similar topics. Diversify the PD programs for teachers so they can choose the set of training that fits their passion such as leadership, research and development, or teaching.

- Allocate and accommodate minimum required PD program hours for teachers. Teachers should have been trained outside of their schools, either in other schools or other institutions. This will allow them to explore and broaden their thinking toward other aspects of teaching; improve their skills in communication, innovation, synthesis, and analytical and critical thinking; introduce them to different class settings; and allow them to share and discuss their knowledge and experiences.

- Sustainable development should be explained to all teachers through the right set of training and conference opportunities. If teachers can adapt the full understanding of how to move toward sustainable development in their lessons, they will ensure that the next generation will be able to face the SDG challenges.

- Annual and/or other periodic evaluations and assessments should use a performance-based assessment (360-degree) mechanism involving all relevant stakeholders (peers, coordinators, DHAs, principals, parents, and MoEHE mentors). The evaluation system should be clear, strict, fair, and consistent. Achieving this will build trust and confidence among teachers, schools, the MoEHE, and society.

- Performance assessments should be different for new teachers as they should have to meet different criteria than more experienced teachers. Assessments should focus on their practices through the induction process. They should not have workloads larger than others, and, in this stage, they should observe and gather confidence, techniques, and answers to their questions.

- Assessments must be merit-based with promotion management and contract continuity. This will support teachers’ social prestige as well.

- Promotion management for teachers must be treated in a much more distinctive way than that of other public services, and the National Human Resource Law should support this not only for nationals but also for expatriates—especially those serving the system for more than five years and willing to continue. These teachers are one of the main drivers of human development. Therefore, they should be sufficiently supported to ensure they remain in the profession.

The recommendations listed above are presented on an implementation roadmap in Figure 8 that includes each recommendation and its impact level, considering the current status of the education system. The roadmap includes some recommendations that will consequently lead to accomplishing others. The colors represent the phases of the teachers’ journeys whereas the shapes indicate the stakeholders’ responsibility for leading and accomplishing each recommendation. Circles, for example, are the responsibility of policymakers. They should initiate the recommendation, and schools and teachers should implement it. On the other hand, squares represent recommendations initiated at the school level and implemented by teachers. Finally, triangles represent recommendations initiated and implemented at the teachers’ level. This plan aims to build up a resilient base for teachers’ career pathways, considering the different elements of the education system and the factors affecting it.

Figure 8.

Roadmap recommendation for teachers’ career pathways.

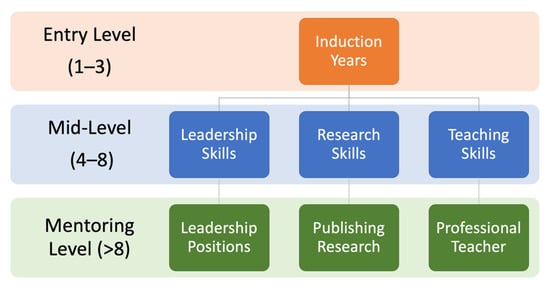

Furthermore, teachers’ PD could be structured as depicted in Figure 9. The first three years of their in-service training should allow teachers to explore diverse training sessions that will give them chances to choose their pathways. After that, teachers should be able to choose their discipline path and become more capable and active within it. This gives teachers chances to attend different training experiences rather than repetitive ones. Moreover, in the future, teachers can lead training sessions; thus not only will they gain knowledge, but they will be able to develop skills and witness their progress throughout their journey. Teachers currently have one way to raise their status—by becoming a coordinator. Otherwise, those who prefer not to handle such a position tend to remain as teachers. This status does not prepare teachers for leadership positions, as they do not receive any leadership training through their career PD. However, this proposed pathway provides opportunities for teachers to be eligible for leadership positions, conduct research, or improve their teaching methods.

Figure 9.

Proposed career pathways for teachers in the QES.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, data curation, and writing of the original draft were the responsibility of W.A.A.-T., the first author. Methodology, reviewing, and editing were the responsibility of I.A., the corresponding author. Conceptualization, supervision of all stages, multiple reviewing, and editing were the responsibility of M.K., the third author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hamad Bin Khalifa University (protocol code 2019-018 and dated 14 May 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments