Reflecting on Existing English for Academic Purposes Practices: Lessons for the Post-COVID Classroom

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- RQ 1.

- How did EAP teachers in Hong Kong cope with the transition to emergency remote teaching?

- RQ 2.

- How did these teachers transition from emergency remote teaching to sustainable EAP technology-enhanced practices?

3. Methodology

3.1. Context of the Study and Participants

- Refer to sources in written texts and oral presentations;

- Paraphrase and summarise materials from written and spoken sources;

- Plan, write, and revise expository essays with references to sources; and

- Deliver effective oral presentations.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- How would you describe your experience teaching EAP during ERT?

- What did you find most useful, and why?

- What did you find most challenging, and why?

- What strategies did you use, and why?

- How has the suspension of in-person teaching affected your classroom practices? If it has changed, what factors influenced the change? If it has not, why not?

- What should be kept or left behind from this experience, and why?

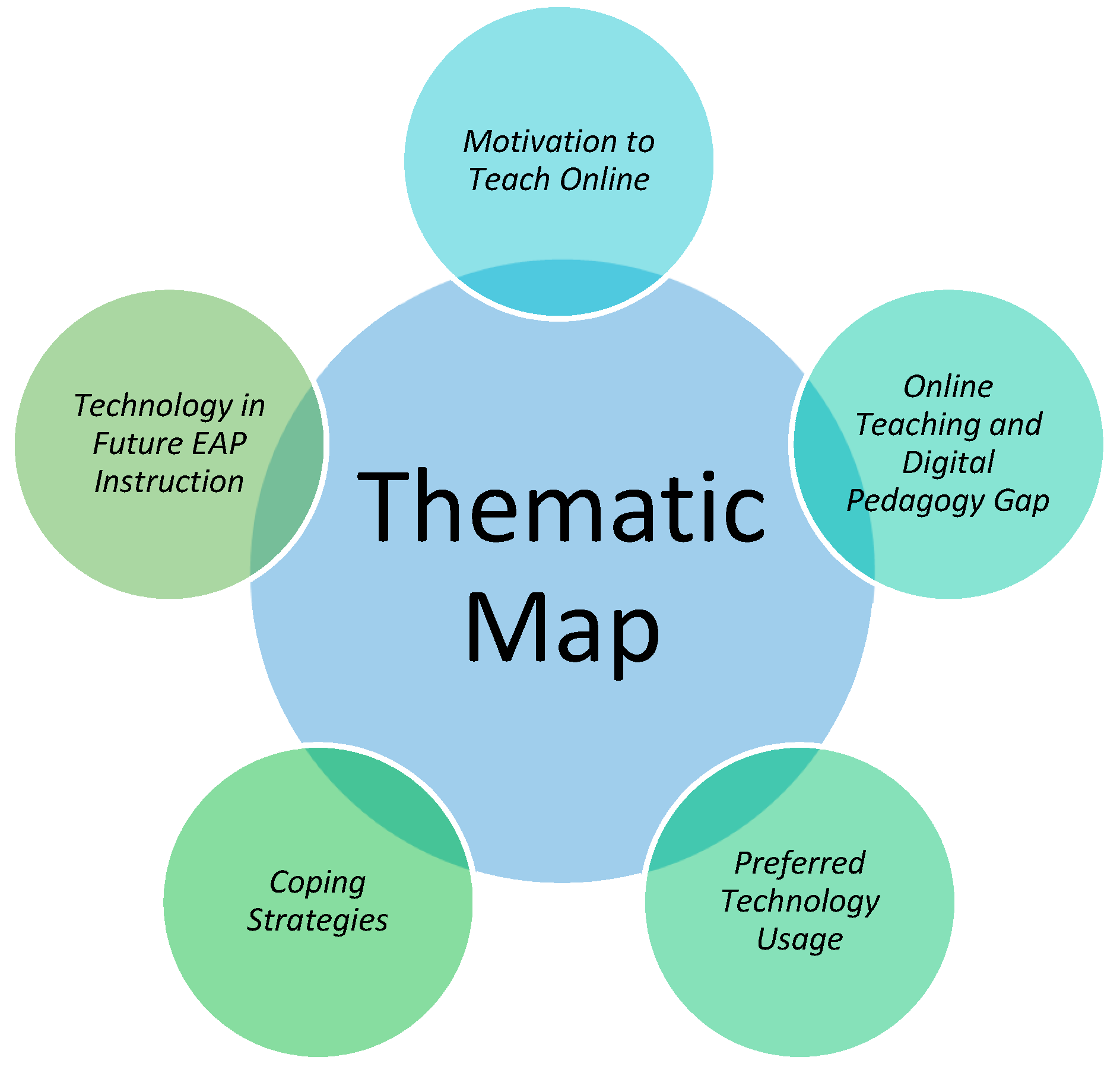

4. Findings Discussion

4.1. Motivation to Teach Online

4.2. Online Teaching and Digital Pedagogy Gap

Okay, so I don’t have enough knowledge of online teaching, and this was something I really had to work on. In the face-to-face classroom, it is easy to connect with my students, understand if they have understood my instruction [and] monitor their learning progress, but in the online classroom, I can’t use the same approach.

I need to be able to select apps that benefit the points I’m trying to convey. Then, I have to figure out how to use them, and how to best and when to integrate them with the teaching material. It is not just telling students to take out their phones and click on something.

In the classroom, I ask them to Google and brainstorm a topic and then present it using a Padlet. Now, when we are online, they first have to go into a breakout room, then share a window, collaborate on the ideas on Padlet, save it and come back to the main room and present what they found. It’s like we are going from one window to the next and so on.

4.3. Preferred Technology Usage

I like to use wikis, as students can together work on a topic, brainstorm initial ideas, start organising their ideas, and then help to write and build their report by self-correcting each other before I clarify both general and specific language items.

In the last couple of years, when we attend conferences or seminars, they tend to be predominantly about technology this or that… I just don’t feel that I need to use it… It just doesn’t add anything extra to my lessons.

4.4. Coping Strategies

I knew I would struggle with online teaching. But the more I taught, the better I felt students responded, and I became more confident to experiment and less anxious. I also received tips and tricks from students, and eventually, I felt my hard work paid off.

4.5. Technology in Future EAP Instruction

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terauchi, H.; Noguchi, J.; Tajino, A. Towards a New Paradigm for English Language Teaching: English for Specific Purposes in Asia and Beyond; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. New Technologies and Language Learning; Palgrave Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kohnke, L.; Jarvis, A.; Ting, A. Digital multimodal composing as authentic assessment in discipline-specific English courses: Insights from ESP learners. TESOL J. 2021, e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Vasquez, C. Web 2. 0 and Second Language Learning: What Does the Research Tell Us? CALICO J. 2012, 29, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Tavares, N.J. From Moodle to Facebook: Exploring students’ motivation and experiences in online communities. Comput. Educ. 2013, 68, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K.; Wong, L.L.C. Innovation and Change in English Language Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review Online, Retrieved 27 April 2021. 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 3 August 2020).

- Kohnke, L.; Moorhouse, B.L. Adopting HyFlex in higher education in response to COVID-19: Students’ perspectives. Open Learn. J. Open Distance e-Learning 2021, 19, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, G. Technology and the future of language teaching. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2018, 51, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, G.; Ahmed, F.; Cole, C.; Johnston, K.P. Not More Technology but More Effective Technology: Examining the State of Technology Integration in EAP Programmes. RELC J. 2020, 51, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, J.; Lee, A. Technology-enhanced language learning (TeLL): An update and a principled framework for English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses / L’Apprentissage des langues assisté par la technologie (TeLL): Mise à jour et énoncé de principes pour les cours. Can. J. Learn. Technol. La Rev. Can. L’Apprentissage Technol. 2014, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Windsor, A.; Park, S.-S. Designing L2 reading to write tasks in online higher education contexts. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2014, 14, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S. Integrating New Technologies into Language Teaching: Two Activities for an EAP Classroom. TESL Can. J. 2004, 22, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berger, J.L.; Van, K.L. Teacher professional identity as multidimensional: Mapping its component and examining their association with general pedagogical beliefs. Educ. Studies. 2018, 45, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, G. The role of language teacher beliefs in an increasingly digitalized communicative world; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jääskelä, P.; Häkkinen, P.; Rasku-Puttonen, H. Teacher beliefs regarding learning, pedagogy, and the use of technology in higher education. J. Res. Technol. Education 2017, 49, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kember, D.; Gow, L. Orientations to teaching and their effect on the quality of student learning. J. High. Education 1994, 65, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, S. Truth, Lies, and Videotapes: Embracing the Contraries of Mathematics Teaching. Elementary Sch. J. 2016, 117, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-S. Examining Current Beliefs, Practices and Barriers About Technology Integration: A Case Study. Tech Trends 2016, 60, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Valcke, M.; van Braak, J.; Tondeur, J. Student teachers’ thinking processes and ICT integration: Predictors of prospective teaching behaviors with educational technology. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P.A.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.; Tondeur, J. Teacher beliefs and uses of technology to support 21st century teaching and learning. In International Handbook of Research on Teacher‘s Beliefs; Fives, H.R., Gill, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G.; Otto, S.E.K.; Ruschoff, B. Historical perspectives on CALL. In Contemp. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn.; Thomas, M., Reinders., H., Warschauer., M., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer, P.A.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.T. Teacher Technology Change: How knowledge, confidence, beliefs, and culture intersect. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2010, 42, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, F.A.; Lowther, D.L. Factors affecting technology integration in K-12 classrooms: A path model. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2009, 58, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P.A.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.T.; Sadik, O.; Sendurur, E.; Sendurur, P. Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: A critical relationship. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifflet, R.; Weilbacker, G. Teacher beliefs and their influence on technology use: A case study. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 2015, 15, 368–394. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.M. The relationship between teachers’ beliefs, teachers’ behaviors, and teachers’ professional development: A literature review. Int. J. Educ. Practice. 2019, 7, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M.J.; Hawk, N.A. The impact of field experiences on prospective preservice teachers’ technology integration beliefs and intentions. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 89, 103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Zheng, X. The rhetoric and the reality: Exploring the dynamics of professional agency in the identity commitment of a Chinese female teacher. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2019, 21, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moate, J.; Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. Identity and Agency Development in a CLIL-based Teacher Education Program. J. Psychol. Lang. Learn. 2020, 2, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, S.M.; Diehl, K.; Trachtman, R. Teacher belief and agency development in bringing change to scale. J. Educ. Chang. 2019, 21, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.F.; Churchill, D. Adoption of mobile devices in teaching: Changes in teacher beliefs, attitudes and anxiety. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2015, 24, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P.A. Addressing first- and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 1999, 47, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowther, D.L.; Inan, F.A.; Strahl, J.D.; Ross, S.M. Does technology integration “work” when key barriers are removed? Educ. Media International 2008, 45, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongkulluksn, V.W.; Xie, K.; Bowman, M.A. The role of value on teachers’ internalization of external barriers and externalization of personal beliefs for classroom technology integration. Comput. Educ. 2018, 118, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradimokhles, H.; Hwang, G.-J. The effect of online vs. blended learning in developing English language skills by nursing student: An experimental study. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericksen, E.; Pickett, A.; Shea, P.; Pelz, W.; Swan, K. Factors Influencing Faculty Satisfaction with Asynchronous Teaching and Learning in the SUNY Learning Network. Online Learn. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolliger, D.U.; Wasilik, O. Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and learning in higher education. Distance Educ. 2009, 30, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, M.Y.; Tang, Y.; Bonk, C.J.; Zhu, M. MOOC instructor motivation and career development. Distance Educ. 2020, 41, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, L. A review of research exploring teacher preparation for the digital age. Camb. J. Educ. 2019, 50, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polly, D.; Mims, C.; Shepherd, C.E.; Inan, F. Evidence of impact: Transforming teacher education with preparing tomorrow’s teachers to teach with technology (PT3) grants. Teach. Teach. Educ. Int. J. Res. Studies 2010, 26, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J.; Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Baran, E. A comprehensive investigation of TPACK within pre-service teachers’ ICT profiles: Mind the gap! Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Sympathy for the devil? A defence of EAP. Lang. Teach. 2018, 51, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.; Murray, N. An Investigation of EAP Teachers’ Views and Experiences of E-Learning Technology. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoliel, J.Q. Grounded Theory and Nursing Knowledge. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 406–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 7th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Harbon, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychology. 2006, 3, 77101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anney, V.N. Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 2014, 5, 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. InThe SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Researc, 3rd ed.; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; Sage: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fossey, E.; Harvey, C.; McDermott, F.; Davidson, L. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry. 2002, 36, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Rudolph, J.; Malkawi, B.; Glowatz, M.; Burton, R.; Magni, P.A.; Lam, S. COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Int. Perspect. Interactions Educ. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yin, H. Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Educ. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, B.L.; Kohnke, L. Thriving or Surviving Emergency Remote Teaching Necessitated by COVID-19: University Teachers’ Perspectives. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.X.; Zhang, L.J. Teacher Learning in Difficult Times: Examining Foreign Language Teachers’ Cognitions About Online Teaching to Tide Over COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brevik, L.M.; Gudmundsdottir, G.B.; Lund, A.; Strømme, T.A. Transformative agency in teacher education: Fostering professional digital competence. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 86, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, R.; Vallade, J.I. Exploring connections in the online learning environment: Student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, O.; Blau, I.; Eshet-Alkalai, Y. How do medium naturalness, teaching-learning interactions and Students’ personality traits affect participation in synchronous E -learning? Internet High. Educ. 2018, 37, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, C.A.; Sauro, S. Introduction to the Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning. In The handbook of technology and second language teaching and learning; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. Learning beliefs and autonomous language learning with technology beyond the classroom. Lang. Aware. 2019, 28, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peachey, N. Synchronous online teaching. In Digital Language Learning and Teaching: Research, Theory, and Practice; Carrier, M., Damerow, R.M., Bailey, K.M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2017; pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rehn, N.; Maor, D.; McConney, A. The specific skills required of teachers who deliver K-12 distance education courses by synchronous videoconference: Implications for training and professional development. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2018, 27, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L. Tech Review: GoSoapBox—Encourage Participation and Interaction in the Language Classroom. RELC J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, B.L.; Kohnke, L. Using Mentimeter to Elicit Student Responses in the EAP/ESP Classroom. RELC J. 2020, 51, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L. Professional Development and ICT: English Language Teachers’ Voices. Online Learn. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J.; Roblin, N.P.; van Braak, J.; Voogt, J.; Prestridge, S. Preparing beginning teachers for technology integration in education: Ready for take-off? Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2016, 26, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, K.L.; Tracey, M.W. Examining the factors of a technology professional development intervention. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2013, 25, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aşık, A.; Köse, S.; Ekşi, G.Y.; Seferoğlu, G.; Pereira, R.; Ekiert, M. ICT integration in English language teacher education: Insights from Turkey, Portugal and Poland. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 33, 708–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licorish, S.A.; Owen, H.E.; Daniel, B.; George, J.L. Students’ perception of Kahoot! ’s influence on teaching and learning. Res. Pr. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2018, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.I.; Tahir, R. The effect of using Kahoot! for learning–A literature review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 149, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M. Collaborating Online with Four Different Google Apps: Benefits to Learning and Usefulness for Future Work. J. Asiat. 2019, 16, 1268–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, R.J. Language learning strategies and beyond: A look at strategies in the context of styles. In Shifting the Instructional Focus to the Learner; Middlebury, V.T. Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages; Magnan, S.S., Ed.; SciePub Journal of Linguistics and Literature: Newark, NJ, USA.

- Nel, L. Students as collaborators in creating meaningful learning experiences in technology-enhanced classrooms: An engaged scholarship approach. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebritchi, M.; Lipschuetz, A.; Santiague, L. Issues and Challenges for Teaching Successful Online Courses in Higher Education. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2017, 46, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychology 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C. The Effects of Flipping an English for Academic Purposes Course. Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2019, 11, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami, F.; Marandi, S.S.; Sotoudehnama, E. Interaction in a discussion list: An exploration of cognitive, social, and teaching presence in teachers’ online collaborations. ReCALL 2018, 30, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basturkmen, H. Review of research into the correspondence between language teachers’ stated beliefs and practices. System 2012, 40, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L.; Jarvis, A. Coping with English for Academic Purposes Provision during COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowsky, M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. Real World Research; Blackwell: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Grenier, R.S. Qualitative Research in practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboke, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Pseudonym | Degree | # of Years of Teaching Experience | # of Years of Teaching Experience on the EAP Course | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Alan | MA | 7 | 2 |

| T2 | Emily | MA | 10 | 2 |

| T3 | John | MA | 16 | 6 |

| T4 | Beth | MA | 8 | 7 |

| T5 | Frank | MA | 11 | 4 |

| T6 | Sara | MA | 14 | 6 |

| T7 | Michael | MA | 16 | 3 |

| T8 | Sophia | MA | 6 | 5 |

| T9 | Adam | MA | 24 | 8 |

| T10 | Oscar | MA | 10 | 7 |

| T11 | Jake | MA | 6 | 1 |

| T12 | Michael | MA | 18 | 4 |

| T13 | Jacob | MA | 9 | 5 |

| T14 | David | MA | 12 | 6 |

| T15 | Dennis | MA | 17 | 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohnke, L.; Zou, D. Reflecting on Existing English for Academic Purposes Practices: Lessons for the Post-COVID Classroom. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011520

Kohnke L, Zou D. Reflecting on Existing English for Academic Purposes Practices: Lessons for the Post-COVID Classroom. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011520

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohnke, Lucas, and Di Zou. 2021. "Reflecting on Existing English for Academic Purposes Practices: Lessons for the Post-COVID Classroom" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011520

APA StyleKohnke, L., & Zou, D. (2021). Reflecting on Existing English for Academic Purposes Practices: Lessons for the Post-COVID Classroom. Sustainability, 13(20), 11520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011520