Spanish Tourist Sector Sustainability: Recovery Plan, Green Jobs and Wellbeing Opportunity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

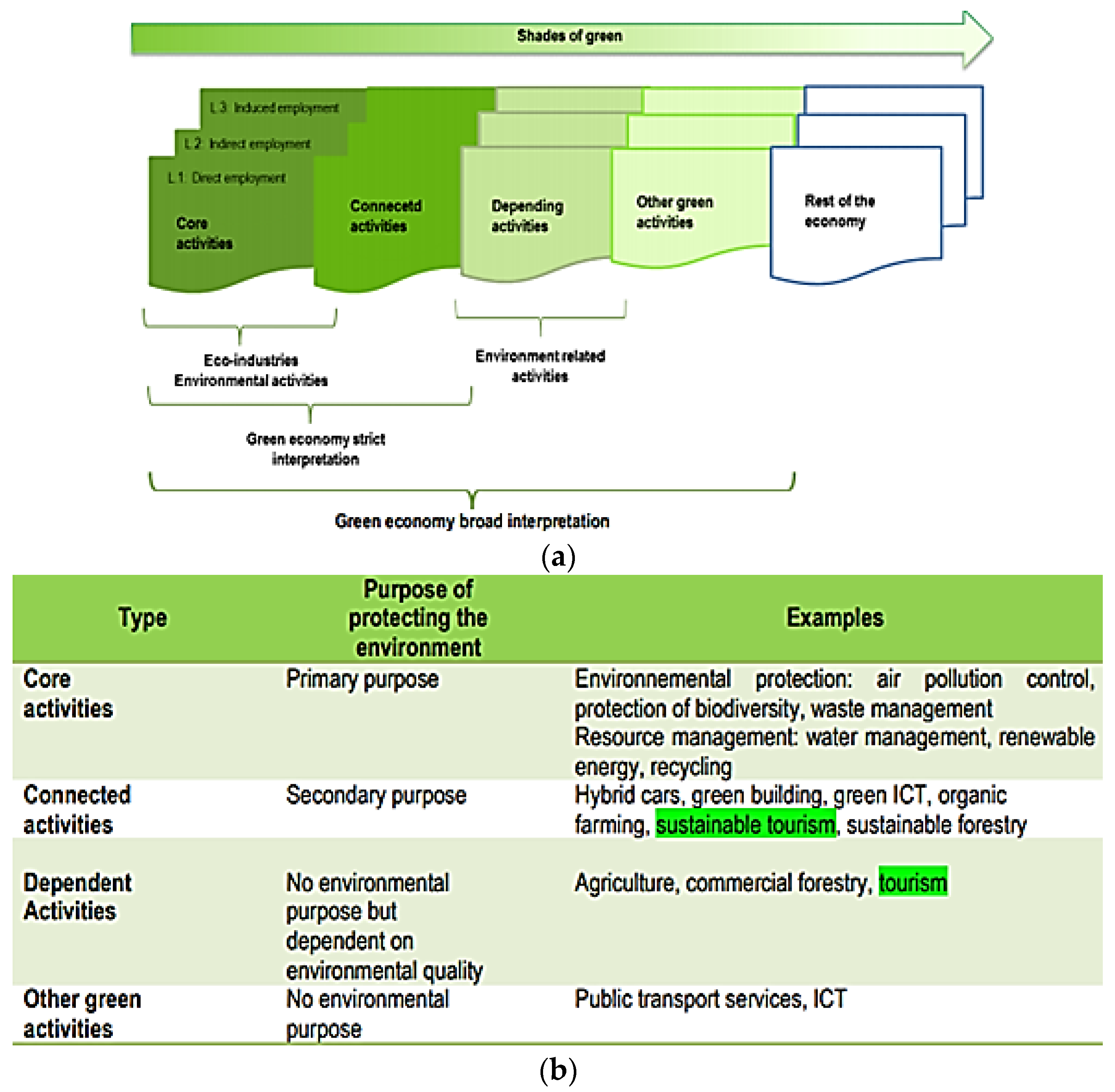

2.1. Sustainable Tourism and Green Jobs

2.2. International Institutions Perspective on Sustainability and Green Jobs

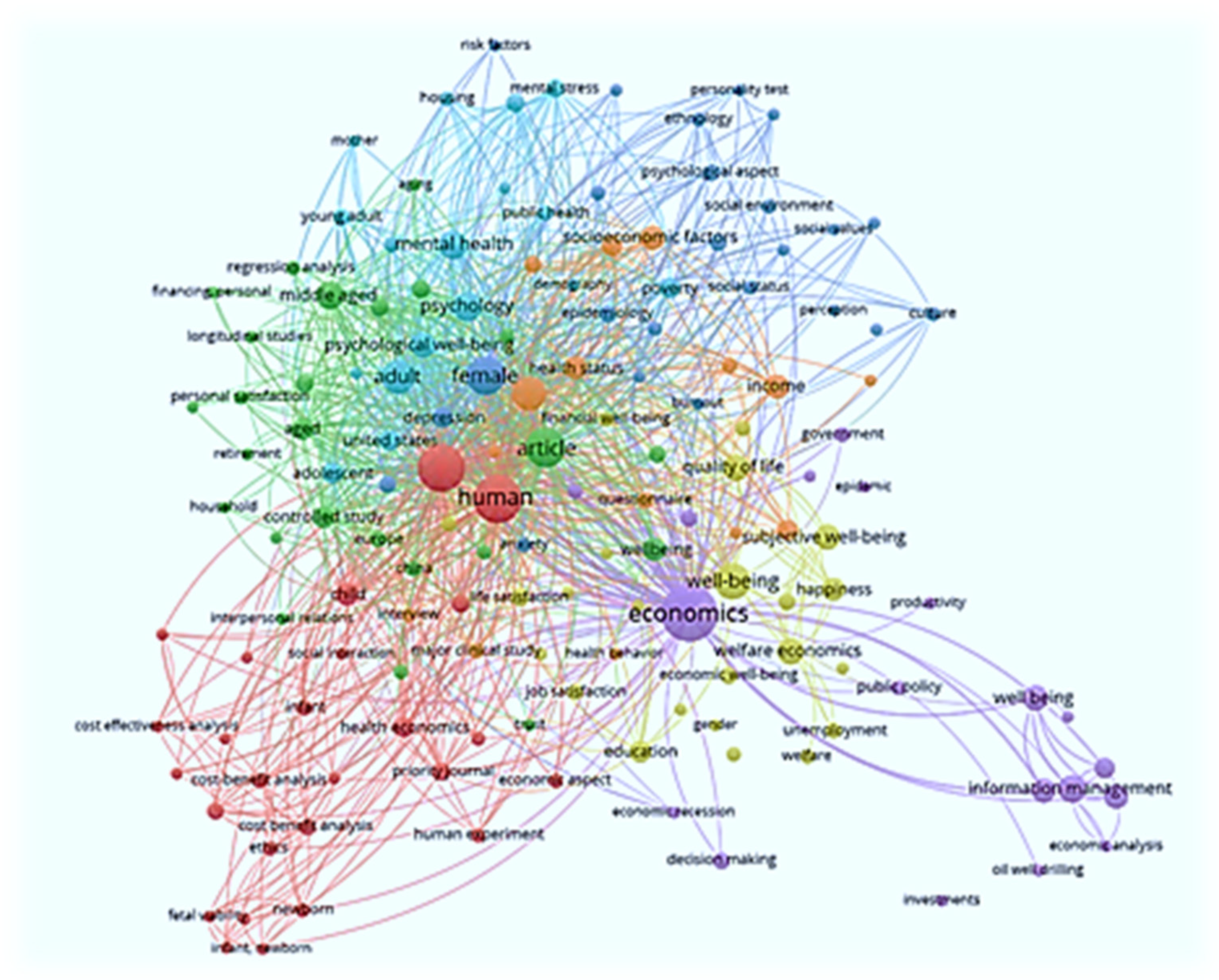

2.3. Academic Literature on Sustainable Tourism and Green Jobs

- 1.

- Determine whether the initial and very optimistic prospect about green jobs as announced by the EU during the Green Deal have been achieved years later in the hospitality sector, which is very relevant for the Spanish economy, providing many green jobs.

- 2.

- Analyze whether main Spanish hotel chains (as a substantial part of the tourism industry in the country) are aligned with Sustainable Development Goals and the other international initiatives in WBE.

- 3.

- Analyze whether Spanish hotel chains are putting in place sustainability systems and EMSs (Environmental Management Systems).

- 4.

- Analyze whether Spanish hotel chains are creating green jobs in both the first definition of green jobs (works in recycling, renewable energies, energy saving and waste disposal, etc.) and in the latest and more generic definition (decent and sustainable jobs and other points related with WBE).

3. Case Study: Green Jobs and Wellbeing Opportunity in Spanish Hospitality

- 1.

- Textual adhesion to SDG: Mention of specific measures and actions put in place by the hotel chain to achieve these goals within their scope.

- 2.

- Sustainability practices: A sample of different sustainability measures regarding recycling, waste disposal, renewable energies, energy savings and/or environmental training are mentioned.

- 3.

- Environmental Management Systems mentioned by the hotel: Any environmental certification system used by the hotel chain and mentioned on the CSR report ( ISOs and eco-labels).

- 4.

- Human resources practices linked to decent jobs: Mention of fair wages, equality-diversity management, non-discrimination and justice.

- 5.

- Green jobs: Any mention to increase of green jobs or green job opportunities on the CSR.

- 1.

- Perspectives for green jobs within Spanish hotels. Is there a significant increase in green jobs at Spanish hospitality? Are Green skills and green profiles important in the hiring processes? Are green skills and competencies more sought after by the Spanish hospitality by now? Is this going to change for the better in the coming future?

- 2.

- Are Spanish hotels complying with SDG? What measures are they implementing?

- Adherence to the SDGs and how they are applied at the hotel chain;

- Good sustainability practices (recycling and energy saving);

- EMSs or Environmental Management Systems and certifications (ISO 14000 and ISO 15000);

- Human resource practices linked to decent work: non-discrimination, equality, justice and fair wages;

- Mention of green jobs in corporate documentation.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. EU Green Week. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/news/eu-green-week-2021-zero-pollution-conclusions-2021-06-04_en (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- European Commission. Renewable Energy Directive. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/topics/renewable-energy/renewable-energy-directive/overview_en (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal COM/2019/640 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Recovery Plan for Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- EUR-Lex. Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 Establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021R0241 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Vindel, J.M.; Trincado, E.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. European Union Green Deal and the Opportunity Cost of Wastewater Treatment Projects. Energies 2021, 14, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yzquierdo, J.H.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. The European transition to a green energy production model. Italian feed-in tariffs scheme & Trentino Alto Adige mini wind farms case study. Small Bus. Int. Rev. 2020, 4, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trincado, E.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Vindel, J.M. The European Union Green Deal: Clean Energy Wellbeing Opportunities and the Risk of the Jevons Paradox. Energies 2021, 14, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Vaquero, M.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Lominchar, J. European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain. Energies 2021, 14, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; García-Vaquero, M.; Lominchar, J. Wellbeing Economics: Beyond the Labour compliance & challenge for business culture. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2021, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bagus, P.; Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. COVID-19 and the Political Economy of Mass Hysteria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Guidelines for a Just Transition towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/publications/WCMS_432859/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- International Labour Organization (ILO) Green Jobs skills. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_709121.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- CEDEFOP. Skills for Green Jobs in Spain: An Update. 2018. Available online: http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/spain_green_jobs_2018.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Eurostat Statistics Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tourism_statistics (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Weforum. The Travel Tourism Competitiveness Report. 2019. Available online: https://es.weforum.org/reports/the-travel-tourism-competitiveness-report-2019 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Trincado, E. Business and labour culture changes in digital paradigm. Cogito 2020, 12, 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Economy of Well-Being. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/about/secretary-general/the-economy-of-well-being-iceland-september-2019.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- WEF. Wellbeing Economy Alliance. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/about#:~:text=The%20Wellbeing%20Economy%20Alliance%20is%20a%2010-year%20project,people%20and%20organisations%20working%20toward%20a%20common%20vision (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- IEA and International Monetary Fund. Sustainable Recovery: World Energy Outlook. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/sustainable-recovery (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Skills-OVATE. Skills Online Vacancy Analysis Tool for Europe. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-visualisations/skills-online-vacancies/skills/occupations (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- OECD. Skills Statistics by Country Stat. 2018. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SKILLS_2018_TOTAL# (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- CEDEFOP. Skills for Green Jobs in Europe. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/3078_en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- O*NET Online. Available online: https://www.onetonline.org (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Brundtland, G.H.; Khalid, M.; Agnelli, S.; Al-Athel, S.; Chidzero, B.J. Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- VV.AA. PNUMA Annual Report. 2007. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org›UNEP_AR_2007_SP (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Measuring Green Jobs. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/green/home.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Deschenes, O. Green Jobs (No. 62); IZA Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Niñerola, A.; Sánchez-Rebull, M.V.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Tourism research on sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B.; Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.L.J. Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development of Tourism. 2012. Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/en/content/about-us-5 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- UNDP. Annual Report 2017. Available online: https://annualreport.undp.org/2017 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Valero-Matas, J.A. El espejismo de una energía social. La economía del hidrógeno. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2010, 68, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNDP. Making Tourism More Sustainable. A Guide for Policy Makers; United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNSD. UN Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- UNCTAD. The Contribution of Tourism to Trade and Development; TD/B/C.I/8; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. 6th International Conference in Tourism Statistics Measuring for Sustainable Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/archive/asia/event/6th-international-conference-tourism-statistics-measuring-sustainable-tourism (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ILO. Sustainable Development, Decent Work and Green Jobs. Report V. International Labour Conference. 102nd Session, Geneva. 2013. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_207370.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- ILO. Green Jobs Programme of the ILO. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_371396.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Poschen, P. Decent Work, Green Jobs and the Sustainable Economy: Solutions for Climate Change and Sustainable Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. ILO Green Jobs. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/WCMS_213842/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Chernyshev, I. Employment, Green Jobs and Sustainable Tourism. Available online: http://webunwto.s3.amazonaws.com/imported_images/48535/chernyshev_conf2017manila_central_paper.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Bilsen, V. Green Jobs. Final Report. IDEA Consult in Collaboration with RDC Environment (3E). Brussels, May 2010. Available online: file:///D:/downloads/Final%20report%20green%20jobs%20IDEA.pd (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Valero-Matas, J.A.; De la Barrera, A. The Autonomous Car: A better future? Sociol. Techscience 2020, 10, 136–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ladkin, A.; Szivas, E. Green jobs and employment in tourism. In Tourism in the Green Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Ministry of Enveronment. Empleo verde en una Economía Sostenible. Available online: http://www.upv.es/contenidos/CAMUNISO/info/U0637188.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Jugault, V. Green Jobs for Sustainable Tourism. Available online: https://webunwto.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/45423/gjasd_international.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Renewable Energy in Europe. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/focus-renewable-energy-europe-2020-mar-18_en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Szako, V. Employment in the Energy Sector; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.; Kuralbayeva, K.; Tipoe, E.L. Characterising green employment: The impacts of ‘greening’on workforce composition. Energy Econ. 2018, 72, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Green Jobs for Sustainable Development, a Case Study for Spain. 2012. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/--emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_186715.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Eures: Short Overview of the Labour Market. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eures/main.jsp?catId=2627&countryId=ES&acro=lmi&lang=en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Labour Markets. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/5734929/KS-HA-12-001-05-EN.PDF.pdf/f60b7339-a767-4400-8036-1d6294913a23?t=1414776599000 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- ILO. Green Skills for Green Jobs. 2011. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/ilo-bookstore/order-online/books/WCMS_159585/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Sanchez, A.B.; Poschen, P. The Social and Decent Work Dimensions of a New Agreement on Climate Change. 2010. Available online: https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/library/ilo22.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Spanish Government. Informe Sobre Empleo Verde. Available online: https://www.empleaverde.es/sites/default/files/informe_empleo_verde.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Towards innovation in sustainable tourism research? J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. The growth and spread of the concept of sustainable tourism: The contribution of institutional initiatives to tourism policy. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branwell, B.; Lane, B. What drives research on sustainable tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, G.C.; Jara, R.M.; Julián, J.R.R.; Bielsa, J.I.G. Study of the effects on employement of public aid to renewable energy sources. Procesos de Mercado: Revista Europea de Economía Política 2010, 7, 13–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sulich, A.; Rutkowska, M. Green jobs, definitional issues, and the employment of young people: An analysis of three European Union countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 262, 110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, R.V.; de Man, F. Tourism Inclusive growth and decent work: A political economy critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, S. Adoption of voluntary environmental tools for sustainable tourism: Analysing the experience of Spanish hotels. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; García-Ramos, M.A. A win-win case of CSR 3.0 for wellbeing economics: Digital currencies as a tool to improve the personnel income, the environmental respect & the general wellness. REVESCO 2021, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Ramos, M.A.G. How to undertake with digital currencies as CSR 3.0 practices in wellbeing economics? J. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M.; Celemín, M.S.; Rubio, L. Use of different sustainability management systems in the hospitality industry. The case of Spanish hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.V. La sostenibilidad ambiental del sector hotelero español. Una contribución al turismo sostenible entre el interés empresarial y el compromiso ambiental. Arbor 2017, 193, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baum, T.; Kralj, A.; Robinson, R.N.; Solnet, D.J. Tourism workforce research: A review, taxonomy and agenda. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 60, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winchenbach, A.; Hanna, P.; Miller, G. Rethinking decent work: The value of dignity in tourism employment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1026–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valero-Matas, J.A. Responsabilidad social de la actividad científica. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2006, 64, 219–242. [Google Scholar]

- Úbeda-García, M.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the hotel industry. The mediating role of green human resource management and environmental outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, S.; Kusluvan, Z.; Ilhan, I.; Buyruk, L. The human dimension: A review of human resources management issues in the tourism and hospitality industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 171–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, M.; Jago, L. A framework for work-life balance practices: Addressing the needs of the tourism industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fortune 2020 List. Available online: https://fortune.com/worlds-best-workplaces/2020/hilton/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Goh, E.; Muskat, B.; Tan, A.H.T. The nexus between sustainable practices in hotels and future Gen Y hospitality students’ career path decisions. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2017, 17, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grolleau, G.; Mzoughi, N.; Pekovic, S. Green not (only) for profit: An empirical examination of the effect of environmental-related standards on employees’ recruitment. Resour. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Sulkowski, A.J. A greener company makes for happier employees more so than does a more valuable one: A regression analysis of employee satisfaction, perceived environmental performance and firm financial value. Interdiscip. Environ. Rev. 2010, 11, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubor, A.; Berber, N.; Aleksić, M.; Bjekić, R. The influence of corporate social responsibility on organizational performance: A research in AP Vojvodina. Anal. Ekon. Fak. Subotici 2020, 43, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Spanish Hotel Employees. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?tpx=37124 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Hosteltur. Ranking Hosteltur Grandes Cadenas Hoteleras. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/139934_ranking-hosteltur-de-grandes-cadenas-hoteleras-2020.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Instituto Tecnológico Hotelero-ITH. Available online: https://www.ithotelero.com/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- López, M.V.; Garcia, A.; Rodriguez, L. Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones sustainability index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Lominchar, J. Labour relations development and changes in digital economy. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2020, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| Hotel | 2019 Turnover (Millions of Euros) |

|---|---|

| Meliá Hotels | 2.846 |

| Iberostar Hotels and Resorts | 2.353 |

| RIU Hotels | 2.240 |

| Barceló | 2.2184 |

| NH Hotel Group | 1.1783 |

| Bahía Principe Hotels and Resorts | 800 |

| Palladium | 752 |

| H10 Hotels | 660 |

| Eurostars Hotel Company | 620 |

| Princess Hotels | 2868 |

| Hotel | Total Hotels | Adhesion to SDG | Sustainable Practices | EMS | Decent Jobs | Mention/Visibility of Green Jobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meliá Hoteles | 367 | YES. Many actions mentioned in all SDG | YES. Energy saving, waste disposal, recycling. Renewable energies | YES | YES. Fair wages, rewards and recognition, non discrimination, diversity management. Employees’ wellbeing | NO textually. Training in environmental and substainability mentioned |

| Iberostar | 118 | YES | YES. Waste disposal, recycling, energy saving | YES | YES. Non discrimination, diversity, fair wages. Employees wellbeing | NO |

| RIU | 92 | YES | YES Waste disposal, recycling, energy savings | YES | YES. Non discrimination, diversity, fair wages | NO |

| Barceló | 265 | YES | YES. Waste disposal, recycling, energy saving | YES | YES. Non discrimination, diversity, employees’s well being | NO |

| NH Hotels | 361 | YES | YES. Waste disposal, recycling, energy saving | YES | YESDiversity management, fair wages based on individual and group performance | NO. Training substainability |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnedo, E.G.; Valero-Matas, J.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. Spanish Tourist Sector Sustainability: Recovery Plan, Green Jobs and Wellbeing Opportunity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011447

Arnedo EG, Valero-Matas JA, Sánchez-Bayón A. Spanish Tourist Sector Sustainability: Recovery Plan, Green Jobs and Wellbeing Opportunity. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011447

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnedo, Esther González, Jesús Alberto Valero-Matas, and Antonio Sánchez-Bayón. 2021. "Spanish Tourist Sector Sustainability: Recovery Plan, Green Jobs and Wellbeing Opportunity" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011447

APA StyleArnedo, E. G., Valero-Matas, J. A., & Sánchez-Bayón, A. (2021). Spanish Tourist Sector Sustainability: Recovery Plan, Green Jobs and Wellbeing Opportunity. Sustainability, 13(20), 11447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011447