Abstract

The aim of this article is an explorative study of the debate on the flood in the western part of Germany in July 2021, based on the comments found below the coverage of a German public television channel (ZDF) published on YouTube. Based on the neopragmatic framing of the analysis by connecting morality and mass media according to Luhmann, as well as Dahrendorf’s conflict theory, four patterns of interpretation were identified which illustrate a high moralization of the conflict: conclusions drawn from the storm (e.g., of a political nature, references to COVID-19, etc.), far-reaching, predominantly negative interpretations that place the storm and its consequences in the context of other negatively interpreted aspects, as well as rational and empathetic interpretations regarding expressions of sympathy and offers of help, and, ultimately, interpretations that range from climate change and planning failures to various conspiracy-theoretical claims of responsibility for the flooding. All in all, a transformation from conflicts of interest and facts to conflicts of identity and values is taking place, revealing two utopias: the utopia in which man and nature are in harmonic unity, as well as the utopia of the satisfaction of individual (material) needs in a stable material-spatial and legal framework. Science has an instrumental application in both utopias.

Keywords:

flood; West Germany; conspiracy theory; conflict; climate change; moralization; Dahrendorf; Luhmann 1. Introduction

In July 2021, Germany experienced its worst natural disaster since the floods on the North Sea coast, particularly Hamburg, in 1962. The flooding in western Germany (the states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate were affected), which followed extremely heavy rainfall, claimed the lives of well over 150 people. Using digital social media, extensive (usually private) relief efforts were spontaneously launched and coordinated; at the same time, a fierce debate broke out on the Internet about the classification of the events. This debate will be examined pars pro toto, embedded in the current state of research on conflicts over spatial change, particularly in the context of measures related to adaptation to and mitigation of anthropogenic climate change in this article [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. More specifically, in this explorative study, we aim to take a closer look at how the flood and its aftermath are interpreted and discussed by users on social media. For this purpose, 1000 comments on the contribution “Das Hochwasser und seine Folgen im Westen Deutschlands” (“The Flood and its Consequences in western Germany”) of the Second German Television (ZDF; public television) made available on the platform YouTube are examined content-analytically and the results are discussed against the background of Niklas Luhmann’s media theory and Ralf Dahrendorf’s conflict theory.

The ‘neopragmatic’ approach, which we follow in this paper, draws on pragmatic tradition, as from U.S. philosophers such as William James, Charles S. Peirce and John Dewey, but also extends it. The orientation of pragmatism towards the effects of action is taken up. Thus, usefulness becomes the touchstone of action, rather than consistency with principles [12,13,14,15]. ‘Truth’, ‘theory’, ‘practice’, etc. are thus no longer thought of separately, but rather form a “unity mediated in the process of experience” [14] (p. 258). In philosophy, ‘neopragmatism’ is particularly associated with Richard Rorty [16,17], but also with Hilary Putnam [18]. As a postmodern approach, neopragmatism rejects notions of universal truth as well as incontrovertible objectivity. Instead, it focuses on pluralistic worldviews and the recognition of contingency, and is normatively oriented towards open-ended, democratic processes of negotiation (see in more detail: [19,20,21]). In current research in spatial and social sciences, the neopragmatism advocated here extends the action reference of pragmatic social and spatial research [3,22,23,24] through its meta-perspective. Complex research objects whose structures are functionally contingently interconnected (see on complexity and space [25,26]) can hardly be treated monotheoretically nor monomethodically (in a meaningful way). The application of different methods and especially theoretical perspectives is appropriate to the complexity of the subject matter (even if basic theoretical stances, such as constructivist and positivist, may well contradict each other [27,28]). The application of different theoretical perspectives must always be reflected and justified with regard to the potential and limits of knowledge. The theoretical as well as methodological openness makes neopragmatic regional research and its multiperspectivity particularly useful for explorative approaches to this complex research object, as it embarks on a search for ‘usable’ knowledge, whereby this principle in turn stands in contradiction to teleological thinking [29,30].

As indicated, a theory triangulation of Niklas Luhmann’s media theory and Ralf Dahrendorf’s conflict theory (on this among others: [31,32,33,34]) in the sense of a ‘neopragmatic approach’ (in summary [35,36,37,38,39]) needs to be justified, since the scientific theoretical foundations are quite different: Luhmann’s approach is based on radical constructivism, whereas Dahrendorf follows critical rationalism. However, both approaches have a complementary framing potential for the question of our investigation: Luhmann deals with the meaning of moral communication, especially in the mass media, and how this leads to conflicts, but does not operationalize these conflicts (i.e., social macro-theory) further. This is where Ralf Dahrendorf’s conflict theory comes in, which, as a social meso-theory, refers to how social conflicts arise and how they can productively contribute to society. This ‘theoretical double strategy’ results in the triangulation of methods, by using qualitative and quantitative methods of media content analysis. These triangulations are complemented by researcher triangulations (with different professional backgrounds, different genders, different stages of scientific careers) and data (the scientific literature, authority statistics, newspaper articles, discussion forums).

In our paper, we first introduce the events surrounding the July flood in West Germany. Then, after a brief presentation of the content of the video, we deal with the theoretical framings, first, the connection between moralizations and mass media, then social conflicts. Next up is the presentation and justification of the methodology of the study, followed by the presentation of the empirical results. Theoretical framings and empirical results are then linked in the ‘Discussion’ section. In the conclusion, we offer further considerations, especially on the unproductivity or productivity of mass-media—based conflict. In doing so, we also identify—based on this explorative study—further potentials for ‘neopragmatic’ approaches to the topic of the mass media construction of anthropogenic climate change and the strategies of mitigation and adaptation.

2. The Events of 14–17 July 2021, in Western Germany and Their Classification

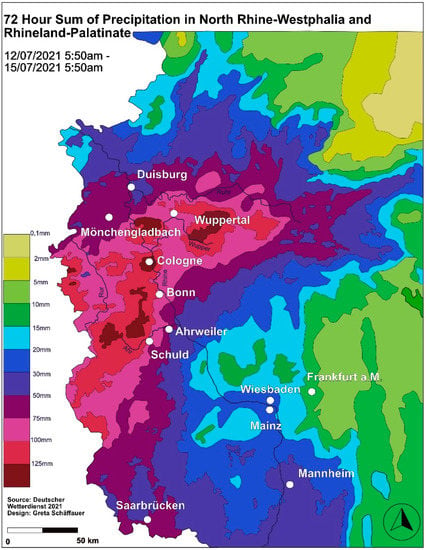

The summer of 2021 was already unusually rainy in western Germany, so that the soils were already highly saturated with water. The severe weather over Belgium and Germany was triggered by the low-pressure system ‘Bernd’, which brought warm, moist, and unstably stratified air from the Mediterranean region to Central Europe, lying between two stable high-pressure areas to the west and east. A low-altitude current allowed the low to remain stationary, the second cause of the locally large amounts of precipitation (the 72 h sum of precipitation in the affected region is shown in Figure 1). The precipitation, which in some cases exceeded 150 mm, hit an area that is particularly susceptible to flooding as a result of geomorphological peculiarities: low mountainous areas with often narrow valleys with steep slopes [40]. In the “Bergisches Land” and especially on the northern edge of the Eifel, these quantities of precipitation that could have been distributed in the lowlands, ran off quickly and caused small rivers and streams to swell. Thus, the previous record level of the Ahr River at Altenahr of 371 cm on 2 June 2016, was surpassed with almost double the value of about 700 cm on 15 July 2021 (the value is an estimate because the gauge was not designed for such a high water level; [41]). Numerous landslides further complicated the situation. The floods damaged and destroyed numerous buildings, infrastructure facilities from bridges to roads and railroad tracks. Mud and debris clogged canals, making it difficult for the water to drain away, the power supply collapsed in the affected areas, and dams threatened to burst. These events were met by a population that was used to floods, but not to floods that rose at such a high speed and were so destructive. Instead of leaving their homes and running for safety, many people tried to minimize the damage to their own homes. It also proved to be problematic that, with the end of the Cold War, the siren warning network in Germany was thinned out considerably, so that the population (especially in the case of power failures) could not be warned sufficiently (e.g., [42]). As of 28 July 2021, 181 deaths had been counted [43].

In the days following the flood disaster, work began on sounding out the damage. At the same time, the German Federal Armed Forces, the Federal Agency for Technical Relief (THW) and fire departments moved in to make infrastructures usable again, to clear cellars of mud and to clean out sewers. Simultaneously, countless private initiatives were developed to help the victims of the disaster. Immediate aid in the form of donations in kind (especially goods for daily use) were collected and brought to the disaster region, and emergency shelters were organized for people who had become homeless. Furthermore, by means of social media, regional radio stations organized fundraising campaigns, and the First German Television (public service) organized a fundraising gala. On the weekends following the floods, professional helpers were often unable to reach the affected regions, because so many helpers had set out to help with the cleanup work that access roads were blocked (an overview is available at [44]). No sooner had the first news about the flood disaster—the extent of which could hardly be estimated at the time—become known, a heated debate broke out on social media about its interpretation and evaluation, the subject of this article.

Figure 1.

The 72 h sum of precipitation in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate, own illustration based on: “Hydro-klimatologische Einordnung der Stark- und Dauerniederschläge in Teilen Deutschlands im Zusammenhang mit dem Tiefdruckgebiet” Bernd “ vom 12. bis 19 July 2021” [45].

3. “The Flood and Its Consequences in the West of Germany”—Key Messages of the Video

The video under investigation, which was published on YouTube on 15 July 2021, covers the flood disaster in the summer of 2021 in western Germany in 41 min. The ZDF special is titled “Das Hochwasser und seine Folgen im Westen Deutschlands” (The Flood and its Consequences in western Germany) and includes reports from the affected regions, as well as interviews with experts from various fields (ZDF = “Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen”; a Germany-wide public television channel with the highest audience market shares of all German TV stations (13.9% in September 2021; [46]). The report begins with private footage from the flooded regions, showing the initial extent of the rainfall. The footage shows, among other things, the masses of water and destroyed houses and cars. In terms of the impact of the floods, ZDF says that 40 people have died, with (at the time of the video’s filming) quite a few people still missing. Among these fatalities are firefighters and other helpers.

Beyond the private shots, there are also camera shots from the ZDF, which were shot from the air or on site. The aerial shots show that many roads are impassable, rivers have burst their banks and a dam has been damaged, threatening to burst. During these on-site shots, various local residents are interviewed, who describe their view of the situation and describe personal fates, such as the unsafe condition of their own homes. Aspects such as solidarity, the extent of the damage and the demand for rapid help from the state are mentioned. Furthermore, politicians such as Malu Dreyer, Prime Minister of Rhineland-Palatinate, and Armin Laschet, Prime Minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, express their sympathy for those affected and promise rapid financial assistance from the federal states and the federal government. Malu Dreyer here speaks of EUR 50 million as immediate aid and demands, in view of this disaster, more climate protection and better flood protection. She also considers the flooding as a motivation to invest more in climate protection in the future.

The ZDF weather editorial team explains the special nature of the heavy rain event, which is unique in its intensity. Furthermore, the aspects of weather development explained above are presented. For comparison with this heavy rain event, earlier floods are included, such as the flood in August 2002, when the Elbe burst its banks and flooded regions, particularly in Saxony. As a more recent example, the 2013 floods are cited, which affected the whole of Central Europe and resulted in damage of around EUR 12 billion.

The ZDF special also looks at Germany’s neighboring countries, such as Belgium, Switzerland and the Netherlands. Similar situations can be observed there to those in western Germany. In the province of Liège, severe flooding has also occurred, there is no electricity and, as of the time of writing, nine deaths have been counted. Regarding the causes and further future flood dangers, experts are consulted, such as the specialist for spatial and environmental planning Prof. Dr. Jörn Birkmann from the University of Stuttgart and the head of the ZDF environmental editorial department Volker Angres. Jörn Birkmann notes that solutions must be found for further heavy rainfall events, for example by using existing roads as drains and combining reconstruction with climate adaptation. In addition, heavy rain hazard maps should be used when building on land. Volker Angres sees not only climate change as a cause of flooding, but also the continuously increasing sealing of land in Germany. Additional reasons cited are river straightening and the loss of floodplain areas that can serve as retention areas. In order to prevent flood events such as these, Volker Angres calls for a new water management, a stop to land sealing and the upgrading of rural areas, where already built-up areas that are no longer in use are reintegrated into the housing market. At the end of the video, the question of whether there is hope for an improvement in the climate situation is answered by saying that the climate system is very fragile and that we must expect further severe weather events.

Before these contents of the video are analyzed in more detail, a presentation of the framing theoretical foundations will now follow.

4. The Theoretical Framework I: Morality and Mass Media

The concept of morality is understood as a system of normative rules and values that (co-)determine people’s actions. This system is the—preliminary—result of social conventionalization processes. While ‘rules’ give clear guidelines for behavior in concrete social situations, ‘values’ are broader: norms formulate facts desired by a society (or at least a large subset of it) [47], they thus serve as orientation [48], they legitimize norms and they form a guide for ‘identifying purposes’ [49]. In doing so, they follow a dichotomous and complementary logic: every ‘value’ is opposed by an ‘unvalue’ or ‘negative value’ [50,51,52]. In the context of morality, ‘good’ is opposed to ‘evil’. Conventions exhibit a degree of variability that allows, for example, conventions to adapt to changing social conditions [53,54]. This variability takes place not only in a temporal context, but also in a social or cultural context. For example, conventions of social interaction differ between proletarian and academic milieus; what is considered desirable in one culture is undesirable in another (sometimes secured with legal consequences). Moreover, Douglas posits, that blame is used in most societies as an effective means of social control, ultimately resulting in ideological domination [55].

Social conventions (such as values) are the result of communication processes, and communication in turn is also based on conventions. The sociologist Niklas Luhmann [56] understands communication as the only original social action, which—if this view is followed—is the foundation of every society. Communication is divided into a threefold selection: information, communication and understanding [56]. Only when these three selections are completely finished is communication successful. Communication can fail in different ways; for example, communication depends on the information being comprehensible, i.e., it has to be suitable for the further communication process.

Even in early modernity, moral norms were grounded in religion. Religion sharply contoured normality against abnormality, “a scheme of generalization transverse to the situational and behavioral type” [56] (p. 126). The modernization of society brought a differentiation of functional systems with specific tasks for society, which was expressed, for example, in a progressive division of labor and the formation of specialized occupational profiles. The differentiation of society meant not least an increase in “conflictuality and the capacity for conflict,” but also a differentiation of moral values [56] (p. 220) and a differentiation of moral ideas, which increasingly competed with religious morality and largely replaced it in the process of the secularization of society. [57]. Moral communication changed its formative medium: it was no longer dominated by Sunday sermons, but increasingly by the press, radio and television [58]. At present, a threefold process of differentiation can be noted in this context:

- The progressive differentiation of society, for example, through increasingly specialized approaches to social challenges (e.g., in the form of specialized job profiles);

- the differentiation of morals through the disappearance of overarching moral obligations;

- the differentiation of communication media through the emergence of digital social media.

This differentiation is contrasted by the longing for unification of the world [59], which uses the code of morality, because this always has a de-differentiating effect, economic questions no longer on the basis of economic criteria and political questions no longer on the basis of political criteria, etc., but rather morally. In place of the consideration of whether something makes economic sense or is politically opportune, a moral judgment takes the place of a factual discussion (for example [60,61]). Gray [30] (p. 12) even assumes that moral communication is a constitutive feature of current socially differentiated democratic societies; they “can hardly communicate factual issues in any other way than in the mode of excitement and indignation”. This simplification comes with some side consequences, for, “when starting points for conflict are already present,” moralization “tends to generalize the material of conflict”. [56] (p. 128). Stigmatizing the acting person as ‘typical’ leads to personally discrediting him or her [60,62,63]. The typification has a far-reaching effect, because “the ideological adversary becomes a pathological case. And with patients one does not discuss, patients must be cured” [50] (p. 47). With another metaphor: “Moralizing communication now treats everyone equally like children, since it does not accept their actions and statements as mature behavior but subjects them to permanent judgment.” [64] (p. 44). This, in turn, is associated with the side effect that those exposed to moralizing would begin to behave like children: “They react out of fear of punishment or seeking praise, or they revolt against the chastisement” [64] (p. 44). The hierarchical superiority of one’s own position and the subordination of the other position associated with moralization is associated with “creating strife, arising from strife, and then exacerbating the strife” ([65] (p. 370)). Moralizations are also difficult to take back (cf. [66]). The differentiation of morals mentioned at the beginning, in turn, increases the complexity of moral communication, because the expected disciplining effect (with regard to the adherence to one’s own social norms; [60,63]) fails to materialize because the target person/target group has other, often incommensurable, morals. This, in turn, is fed back by the increase in the importance of electronic social media. Particular morals are recursively consolidated and made absolute in echo chambers, the moralization of the other on their basis then breaks out, for example, in discussion forums on contributions by the ‘classic mass media’, such as the press, radio and television [67,68,69,70,71], which in turn makes the study of these forums very fruitful for scientific insights into the genesis and development of social conflicts [72,73,74]. Hereof, the ambiguity of the Internet as a medium becomes clear [75] (p. 127): “Never in the history of mankind has there been such an opportunity for freedom of expression as this. And never before have the evils of unlimited freedom of expression—death threats, pedophilic images, sewage floods of abuse—flowed so easily across borders.”

5. The Theoretical Framework II: Ralf Dahrendorf’s Conflict Theory

In the previous section, we addressed conflicts that develop from the application of moralizations on the one hand and from the application of different morals on the other. In the following, we will now address the question of how conflicts arise and how they can be regulated so that they can develop their productive potential and not have a destructive effect. For this purpose, as announced at the outset, we will draw on the conflict theory of Ralf Dahrendorf, a German-British sociologist and political theorist who was concerned with social conflicts throughout his academic life (inter alia. [76,77,78,79,80,81]; summarized: [82,83,84,85]).

Before approaching the details of Ralf Dahrendorf’s conflict theory, we will—in the spirit of neopragmatic framing—take a look at alternative but unused theories of social conflict.

Social conflicts form an essential element of societies and have been a central subject of social science research from early on (an overview: [86]). For Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, social conflicts are triggers for revolutions and thus are motors of social development [87]. Georg Simmel counters this macro-sociological perspective with a micro-sociological one by locating the driving forces for social conflict in the subject’s drive and interest in certain objects [88]. Like Marx and Engels, social conflicts are not dysfunctional for Simmel, as they are for Talcott Parsons [89], who viewed them—again macrosociologically—as a disruption of the functional structure of society. Pierre Bourdieu, in turn, focused his conflict theory on the mechanisms of distribution of symbolic capital, as well as on how, using economic, social and cultural capital, conflicts are played out in the fields of society (roughly to compare with Parsons’ social subsystems) according to different rules of the game, integrating the micro- into the macrosociological perspective [90,91,92]. In this study, however, we follow the conflict theory of Ralf Dahrendorf, who, on the one hand, adopts a meso-sociological perspective and analyzes typical courses of social conflicts as well as giving indications under which framework conditions social conflicts can be productive for social development and under which they are not. Due to this combination, his conflict theory stands out among the alternatives ones by providing the theoretical framework in which individual conflicts can be understood against the background of social developments.

The starting point for Dahrendorf is to establish the normality of social conflict, so the idea “may be unpleasant and disturbing that there is conflict wherever we find social life: it is nonetheless inevitable for our understanding of social problems” [93] (p. 261). However, Dahrendorf does not merely state the normality, but rather states for him a constructive significance of conflicts for the development of societies: “In conflict lies [...] the creative core of all society and the chance of freedom.” [94] (p. 235). Hereby he distances himself from conservative ideas of a normative ‘natural’ or ‘God-given’ harmony as well as from socialist utopias of a conflict-free final society. Both would bring social developments to a standstill and minimize individual chances in life, especially with regard to the possibilities of individuals to have an innovative effect in societies through their achievements [95,96].

Constitutively supra-individual, social conflicts, as Dahrendorf [78] notes, follow a characteristic pattern: in the first phase of the ‘structural initial situation’, ‘quasi-groups’ emerge initially, which—in certain contexts—have similar interests. In the second phase, the ‘awareness of latent interests’, the conflict parties emerge as the ‘quasi-groups’ become aware of their interests. In the third phase, the ‘phase of formed interests,’ the degree of organization of the conflict parties increases “with a visible identity of their own” [78] (p. 36). Now, the conflict parties face each other dichotomously and differentiated interpretations of the conflict’s object and form are transformed into internal conflicts within the individual conflict parties [78]. For Dahrendorf [78], there are three principal possibilities in dealing with conflicts: their suppression, their solution and their regulation. He rejects the first two possibilities, as in suppression, neither the object nor the cause of the conflict are eliminated, but rather an eruptive (and violent) outbreak threatens. Solution is rejected, because it is connected with the elimination of the social antagonisms underlying the conflict, and is therefore utopian, because there is no society without social antagonisms (this is also not desirable). The method of dealing with conflicts favored by Dahrendorf, their settlement, is characterized by five aspects:

- The concrete conflict (as in social conflicts in general) must be recognized by the conflict parties as normal (not as a contradiction to the ideal of a ‘harmonious conflict-free’ society).

- The settlement refers to a concrete object of conflict, as well as to forms and manifestations of the conflict. It does not refer to the social causes of the conflict (this means an attempt to resolve it).

- A high degree of organization of the conflict parties increases the chance of a settlement of the conflict.

- The success of conflict resolution, in turn, depends on the conflict parties’ compliance with rules. This compliance also refers to the mutual recognition of the equal value of the conflict parties as well as the fundamental justification of the world view of the respective other conflict party.

- The ability to regulate a social conflict depends on the existence of an institutional framework. This framework is formed by a third authority that sets binding rules for dealing with conflicts and has the means to end the conflict externally if necessary. This is what Dahrendorf calls [97] (p. 385) “freedom under the protection of the law”. This authority, in turn, is subject to the imputability of responsibility for its decisions, for example, through a rotational review of satisfaction by the electorate [98].

Conflicts can additionally be differentiated in terms of their subject matter [99,100]: Factual conflicts refer to the concrete facts of the matter (such as whether a mobile or immobile protective device is more suitable for flood prevention at the specific location), while procedural conflicts refer to the type of conflict regulation (such as the type and extent of citizen and expert participation). Conflicts of identity relate to the construction of collective identities, in particular, in order to distinguish them from others (“we affected people” go “the wise guys”), and conflicts of values finally relate to fundamental and incommensurably constructed world views (e.g., advocacy of the “ecosocial transformation” versus defense of the “harmonious homeland”). The controllability of conflicts thereby decreases from the factual to the procedural and identity to the value dimension. In the following, we will deal—with the manifestation of conflicts around the July flood in western Germany—with the handling of the underlying conflicts.

6. The Methodology of the Study

In the sense of the neopragmatic approach, the discussion about the flood is also examined on the basis of the comments below the video on the platform “YouTube”, with a method mix of qualitative and quantitative analysis: a quantitative categorization, as well as a qualitative content analysis of the 1000 comments considered. In total, a data corpus of about 55,000 words was analyzed. The comments analyzed were the first 1000 comments published under the video (of a total of 3474 comments in response to the video as of 8 October 2021). Due to the high number of sub-comments, only comments responding directly to the video content (not to another comment) were considered. Advertisements and links to pornographic content were not considered. The sample size may be small, but this number is quite sufficient for the investigation in the form of an explorative study. Even before the number of comments examined had been reached, no new patterns of interpretation were found. In this respect, the inclusion of further comments would not have yielded any qualitative gain in information, especially since an in-depth qualitative investigation by means of theoretical sampling is not possible with this method, since neither the gender nor the place of residence or age of the commentators are known from the data basis. The qualitative analysis aims to identify typical differentiated patterns of interpretation and evaluation; with the quantitative analysis, we estimate frequencies in relation to three inductively determined categories. The analysis is complemented by a quantitative word frequency analysis, which is presented graphically in the form of a word cloud and can provide information about frequently addressed topics.

For the quantitative categorization, the comments were first copied into Excel, screened, and coded using an inductively developed scoring matrix. After an initial review, three main sentiments and consequently categories according to moralization were identified: ‘hostility’, ‘objectivity’ and ‘empathy’. The categorizations and their definitions were recorded in the excel spreadsheet. The first analysis revealed that comments about politicians, such as Armin Laschet, Malu Dreyer and Angela Merkel, as well as topics such as the broadcasting fees or the ZDF, are to be rated in the hostility category. Comments about conspiracy theories (chemtrails, HAARP), God and the actions of politicians were analyzed in the objectivity category. Offers of help, donations and expressions of sympathy were rated in the empathy category. In a second review, comments were rated in all three categories. They were assigned the numbers one to five. One represents the category ‘does not apply’, two ‘rather does not apply’, three ‘partially applies’, four ‘rather applies’ and five ‘fully applies’. For each comment, all three inductively determined categories—‘hostility’, ‘objectivity’, and ‘empathy’—were scored. Some comments could not be translated into German from various foreign languages. These were scored as zero (as in Figure 2, in 7—Empirical Results).

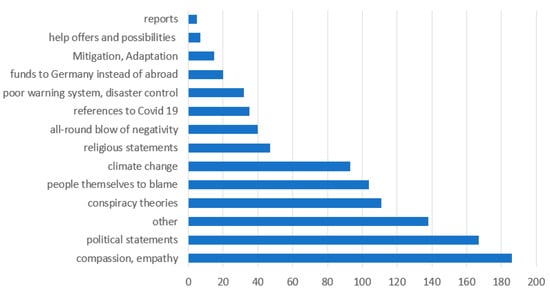

The qualitative content analysis of the 1000 studied comments was initially based on the inductive formation of a code system, based on the evident interpretations and attributions of the flood and its aftermath. Overall, the qualitative content analysis was oriented on the content analysis according to Mayring [101]. In the end, a complex code system was developed, where each comment could be assigned a code. A distribution of the developed codes, and the number of comments assigned to each, is shown in Figure 5 (in 7—Empirical Results). To gain further insight into the present interpretations and attributions of the flood and its aftermath, different patterns of interpretation were derived based on the developed code system. Each pattern represents an identified perspective on the event, which will be presented in more detail in the following chapter.

In addition to the quantitative categorization and qualitative content analysis, a quantitative word frequency analysis was also carried out as a way to visualize frequently used words. The 1000 anonymized comments were inserted, adjusted and finally displayed on the wordart.com (accessed on 19 August 2021) website (Figure 6, in part 7—Empirical Findings). During the adjustment, articles and certain filler words such as ‘and’ were excluded from the analysis. Since the program does not detect word duplications or spelling errors, these were checked and, if necessary, eliminated or combined into one word to determine the correct word frequency.

7. Empirical Results

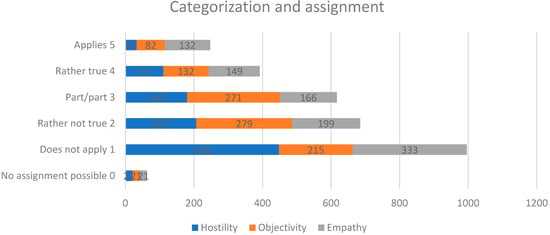

The following paragraphs present the empirical findings of analyzing the 1000 considered comments. The first step is to look at the quantitative categorization of the comments in order to gain an initial insight into the discussion, followed by a more in-depth look at the patterns of interpretation identified in the qualitative analysis. In the quantitative categorization of comments, 21 of the 1000 comments could not be translated and are therefore scored as zero. The most common category determination was ‘does not apply’. Among these, 448 comments were categorized as non-hostile, 215 comments were categorized as non-objective, and 333 comments were categorized as non-empathetic. A total of 685 comments were classified as number 2, ‘rather not true’. A total of 207 comments wew in the area of hostility, 279 in the category of objectivity and 199 in the area of empathy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Categorization and assignment of the 1000 comments (own representation based on own survey 2021).

In total, 144 comments were categorized as rather or fully hostile. It was noticeable that the ‘hostility’ was directed mainly against the politicians. A total of 180 comments were partially hostile and partially not. Very or rather objective were 214 of the 1000 comments. A similar situation can be observed in the ‘empathy’ category. Here, 281 comments were categorized as rather or fully empathic.

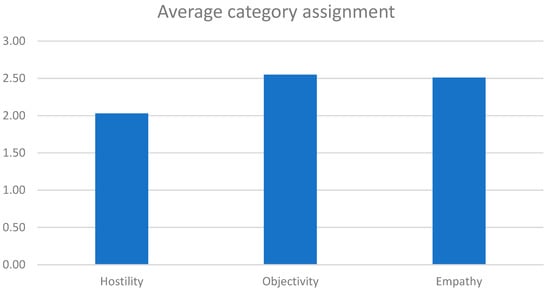

Excel was used to calculate the average assignment (Figure 3). The average value of the category ‘hostility’ was 2.03 and thus at ‘tends not to apply’. The categories ‘objectivity‘ and empathy were 2.55 and 2.51, respectively, and thus between ‘tends not to apply’ and ‘somewhat/partly applies’. It can be observed that all three categories can be located between ‘rather disagree’ and ‘partly agree’ and can therefore be assigned to a predominantly moderate range.

Figure 3.

Average category assignments of the 1000 YouTube comments (own representation based on own survey 2021).

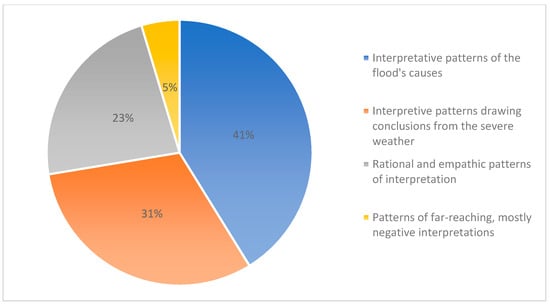

In the qualitative content analysis of the comments, in addition to those from which no interpretation of the video content was apparent—including far-reaching links, comments that cannot be translated into German without further knowledge and comments from which no interpretation of the flood was apparent (“other”; a total of 132 comments, which will not be discussed further below due to lack of relevance)—four other forms of interpretation in particular could be identified: inferences are drawn from the sequences shown in the video (1), the content stimulates a wide-ranging, mostly negative expression of opinion (2) and people react to the video with rational and empathetic comments (3). In particular, however, there were various attempts to discuss the reasons why the flood was caused (4) (see also Figure 4). According to these patterns of interpretation, a closer look at the patterns of interpretation discernible from the comments takes place in the following paragraphs. It should be noted that the majority of the comments—as far as can be seen—were not published by those affected by the flood; accordingly, the patterns of interpretation identified predominantly represent the interpretation of people who were not affected themselves. Based on the inductive coding of the comments, in a further step it was possible to work out four patterns of interpretation of the floods, which will be elaborated on in more detail in the following paragraphs. This consideration is supplemented by exemplary comments that illustrate the expression and tone of the discussion. It should be noted that the commentators’ handling of the rules of German spelling and grammar was very casual. Therefore, the examples shown here have been adapted for better comprehensibility.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the four identified interpretation patterns by percent, the sample size amounts to 868 without the comments categorized as “other” (own representation based on own survey, 2021).

7.1. Interpretive Patterns Drawing Conclusions from the Severe Weather

A total of 269 of the comments examined revealed conclusions drawn by the commentators from the storms, in particular interpretations with political connotations (a total of 155 comments, see Figure 4). However, these were predominantly negative: “If the water comes, the media-hungry politicians will puke” (K776). The political reaction to the storm is seen as a prime example of “not needing a caste called ‘professional politicians’” (K038), and some of the comments accuse politicians of not providing good help: “Just hollow phrases. If the political busybodies had rather taken a shovel in [their] hands. And brought clothes and food to those affected instead of putting themselves in the limelight in a media-effective way and then laughing like idiots. The people need energetic help, not gossip” (K041). Special reproaches are addressed thereby directly to Armin Laschet (Prime Minister of North Rhine-Westphalia), because he should have “the missing flood precaution to answer for and push[e] everything on the alleged climatic change” (K320). In addition, the German chancellor Angela Merkel and Malu Dreyer (Prime Minister of Rhineland-Palatinate) are mentioned by name. The high importance of politics in the discussion about the storm, its causes and consequences are also particularly evident in Figure 5, showing the word frequencies of the analyzed comments. In addition, connections are made to the federal election in September, which on the one hand classify the political behavior (“And the politicians make a promotion tour out of it to catch votes in September”, K784), and on the other hand the interpretations go partly to the extent that connections between major elections and flood events are assumed: “On the subject of floods and election in DE. Election 1990 flood—Election 1994 flood 1993 and 1995 Election 1998 flood 1999 Election 2002 flood 2002 Election 2005 flood 2005 Election 2009 flood 2009 in Bavaria Election 2013 flood 2013 Election 2017 flood 2017 Election 2021 flood 2021 (Coincidence! All coincidence?! Certainly not.)” (K373). Similarly, speculation about financial support from the state can be found, but even these are often framed pessimistically, as the support would be misapplied: “I do not want to write Evil but realistic. Dear Federal Government immediately stop all EU Covid 19 aid and build our country with this money. Immediately!!! No long debates no long discussions stop and pay out. This time Germany needs its money itself” (K470), or more clearly: “Our tax money should be used for such situations and not given away to the whole world!!!” (K911). In this context, the expectation towards other countries to now support Germany financially is recognizable in some of the comments: “Let’s see if now as much help comes from the countries we have [helped] in the course of time as Germany has always distributed so abundantly. I don’t just mean financial aid […] “ (K737). Other commenters draw a more pragmatic conclusion from the storm: that the warning system and the handling of the flood was poor. “Here you really have to ask yourself, why weren’t people warned and what do we have early warning systems for in Germany???” (K326). Likewise, there are doubts about the deployment of aid workers and calls for more commitment: “And the police and fire department send helpers away. Politics does nothing, what do the Bundies [short for soldiers] do? They have nothing to do, go there!” (K227). Other commentators see the storm as finally available proof that the Covid 19 pandemic was much more insignificant than generally portrayed: “And suddenly Covid 19 moves into the background, fortunately, because now it’s really about lives...” (K909). On the other hand, a lack of adherence to the mask requirement in the scenes of the video is criticized and a wait-and-see attitude is taken towards the future, as “First Covid 19 now flooding [...] What’s next?” (K642). Complementary demands for increased mitigation and adaptation become clear, because their insufficient attention by politicians is partly responsible for the damage of the flood:“POLITICS blames I failure on climate change, there have been much worse floods, now they have let the infrastructure decay for decades and that takes revenge.” (K129), or more succinctly, “Maybe flood protection instead of climate protection?” (K303). In parts, the comments examined also include direct apportionment of blame: “To Ms. Dreyer: Anyone who blames climate change for the flood and wants to change the climate back, whose mental suitability for an elective office I must doubt very much...this is a weather catastrophe. We have to deal with it and protect people as best we can.” (K277). Overall, in the aftermath of the storms, there are corresponding interpretations of political failure, personal attacks on political decision-makers, and criticisms of the warning systems and disaster management, which ultimately lead to connections with the COVID 19 pandemic and pleas for a strengthening of climate adaptations.

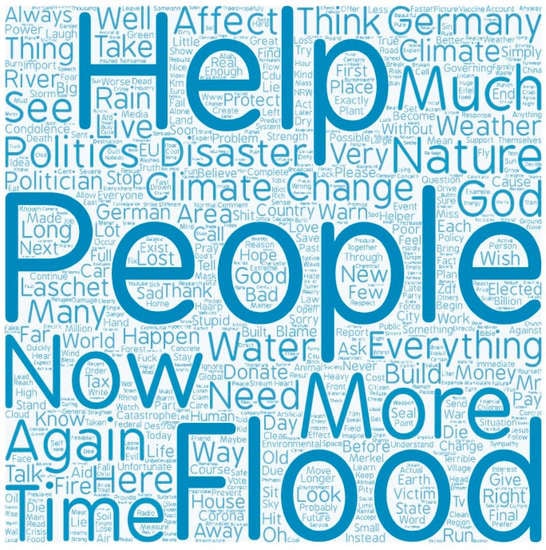

Figure 5.

Word cloud of the examined 1000 comments below the analyzed video. (Own representation using wordart.com; accessed on 19 August 2021; based on own survey 2021).

7.2. Patterns of Far-Reaching, Mostly Negative Interpretations

For some commentators, the coverage of the storm and its consequences provides reasons to express their frustration about what they have seen, as well as various other social and political aspects (a total of 38 comments, see Figure 4). For example, people doubt that the reason for the flood is to be found in climate change, express political disappointment via the question of why warnings were not issued in time, and, finally, to use comparisons to the Christian Flood (cf. K015). Accordingly, the storm and its consequences serve as a stimulus for further, predominantly negative expressions of opinion, as well as associated suggestions of a possibly better implementation: “I also think it’s a pity that only people with a migration background were interviewed. Were there no Germans there. The people there have to be helped, so you can do without gender crap. And what does that have to do with CO2? And take Laschet away, he is totally out of place there.” (K992). Overall, some of the comments contained a wide range of negative opinions, based on far-reaching negative interpretations of the flood and its consequences in western Germany.

7.3. Rational and Empathic Patterns of Interpretation

In this pattern of interpretation, a total of 198 comments conveyed sympathy and compassion (see Figure 6), in addition to reports and offers of help. “My deepest sympathy to those affected! Much strength for the next time! Hopefully there will be no more human losses. Would be nice if the existences could be rebuilt as painlessly as possible! […]“ (K025). These are not only from Germany, but come from different countries, written in various languages: “I hope it will be back to normal as soon as possible. Stay strong everyone. Much love from Tokyo, Japan” (K018) or “courage a vous, de tout coeur avec vous” (K091). Reports about the floods were identified only five times within the analyzed comments, and it can be assumed that the focus of affected people was taken up by the situation on site. Only in one of the comments is the situation clarified: “My beautiful hometown: (I got out at just before one meter, that was a good decision by the way! My losses refer only to my apartment and my inventory (about 3000€) others it has hit much worse ... Homeless I am now for the time being nevertheless to find an apartment here is very difficult” (K551). Beyond that, inquiries are found for donation possibilities and offers of assistance to support those affected. Accordingly, a large proportion of the comments contain rational expressions of sympathy and offers of help, which contrast with the comments, some of which are negative, apportion blame and seek causes.

Figure 6.

Number of comments assigned to the inductively developed codes. If comments could not be clearly assigned to individual codes—for example, religious references that could also be interpreted as conspiracy theories—the dominant code was selected. For the present study, it was already possible to obtain far-reaching information with this procedure, but it opens up the possibility of examining these overlaps more closely in future studies. (own representation based on own survey 2021).

7.4. Interpretative Patterns of the Flood’s Causes

With a total of 309 comments that could be assigned to this interpretation pattern, this is the most frequently identified interpretation pattern (Figure 4). Most frequently, the causation of the flood is associated with climate change. However, it must be noted here that the storm is seen both as a confirmation of climate change and its effects (e.g., K183: “To all car drivers, meat eaters; single-family home dwellers, Greta haters, climate change deniers and vaccination opponents! YOU ASKED FOR IT! These are the effects of a climate sow lifestyle!”, a total of 93 comments, here the transformation from a factual conflict to an identity and value conflict is also evident, as well as “climate lies” (K161), “climate protection propaganda” (K394) and “scaremongering” (K907: “Again this scaremongering by the government! I’m an opponent of flooding, it’s only a light rain!”) is classified. Thus, on the one hand, there is a call for increased climate protection, while at the same time climate change is negated. Climate change is only associated with warming, and climatic changes are interpreted as normal developments: “Of course, climate change is to blame. There have never been flood disasters before [...] The way the Greens directly exploit this is absolutely disgusting” (K762). In the discussion about flooding, the high importance of climate change becomes evident by the analyzed word frequencies, which are visualized in a word cloud shown in Figure 6. However, it is not clear whether climate change is confirmed by the storm or continues to be denied. Furthermore, in a large number of comments, the blame for the flood and its consequences is attributed to the people themselves, which pints out the moral charge of the discussion in the comments (a total of 95 comments). In addition to alleged misconduct in the immediate run-up to the storm, particular reference is made to a “planning failure” of recent years, especially land sealing and the construction of settlements in flood plains and floodplains: “Because soils are sealed, everything is built up and rivers that need space are diverted into canals. Everything only around more building land to get. Nature is displaced and that is the receipt. […] “ (K144). In parts, there is even a direct attribution of blame to those affected: “[...] my condolences to the relatives of the dead, but whoever builds in a flooded area must expect that this will happen” (K039). Another interpretation is the assumption that the storm is a punishment of nature for the ‘bad handling’ by mankind. Thereby, in parts, a personification of nature takes place, because it “strikes back” (K794). A similar interpretation can be found in religious references drawn in connection with the floods (47 comments in total): In parts, the flood is interpreted as God’s punishment for people’s sinful behavior and analogies to the Flood are often referred to (e.g., K946: “God gave the rainbow after the Flood as a sign of peace, but man uses the rainbow for something else...no wonder then that God allows such (floods)...he calls sinners to himself...”). Moreover, many of the commenters see the reasons for the floods as clearly rooted in conspiracy theories: “Who ordered these floods? It’s clear that [...] weather manipulation is taking place! First Covid 19 now water! What do they want from us? Mass destruction?” (K521). The storm is said to have been influenced by means of chemicals and thus could be used as a “climate weapon” (K213): “That was indeed ‘man-made’, but not by too much CO2 but probably by H.A.A.R.P. and geoengineering, the conscious and deliberate manipulation of weather and climate by ‘science’ and the military, worldwide on behalf of governments!!!” (K495). Chemtrails and “HAARP” are mentioned (among others K315) which are said to be responsible for the extreme weather, justifying their use in “weather manipulation to push through the climate agenda!” (K217). Often there is a comparison to the COVID 19 pandemic, which is now followed by severe weather: “[...] This is not a natural disaster!!! Who has staged pandemic, who has also caused floods, this is NOT a NATURAL disaster!!!! […]” (K124). In addition to these explicitly named triggers of the storm, there are also a variety of criticisms of the public broadcasters to be found, who are accused of misinformation. Amongst other things they are called “propaganda television” (K048) and, not least, are accused of complicity: “the consequences? Total loss of confidence in the state media, which, despite knowledge, refrained from warning the people.” (K334). At the same time, however, the request is made: “Send us helpers instead of reporters!” (K473). Overall, the speculations of the commentators regarding the causation of the flood can be divided into two categories: Reasons that can be located beyond the current scientific consensus and those reasons that are based on scientific evidence. In addition, the comments examined often involve personal attacks on fellow commentators, as well as blaming institutions and political figures.

Overall, only a very small proportion of the comments reflect on the opinions expressed. Although some comments are the subject of lively discussions about their correctness, agreement or justification, conclusions are only very rarely drawn from the comments read. If a reflection does take place, however, it usually results in a request to close the comment function below the video: “Please, please close the comment bar. What is written by lateral thinkers is inconceivable, unrealistic and unworthy of human beings.” (K983; In Germany, “Querdenker” (roughly: unconventional thinkers) is the name given to a movement that opposes government measures to contain the COVID 19 pandemic). Because: “The next catastrophe is the comment process here ... who is to blame? Who didn’t do what, politics failed, the community would have failed, climate change is to blame ... etc. Many many THANKS to all who helped and still help!!!” (K119). The political classification of the comments made here also points to a frequently recognizable skepticism within the comments towards the recognized scientific, social and political consensus and a turn towards alternative, socially less accepted theories and world views (conspiracy theories).

8. Discussion

Against the background of the theoretical foundations of the presented investigation, a high degree of moralization of communication on the one hand and a high degree of conflict on the other hand can be observed. The presented investigation shows a high degree of ‘pre-generalization’ of the conflict. The focus of the discussion is not on the flood and how to deal with it, but this is fitted into pre-formed patterns of interpretation and evaluation and is morally charged. In this respect, the incomplete communication (because the step of ‘understanding’ the utterance of those who do not follow one’s own interpretation of the world is suppressed) has something ritualistic about it; the conflict is actualized on different occasions, in this case a concrete flood. Following the logic of moral communication [60], this takes place in large parts in an individualized way and is aimed at discrediting the person who has a different (also moral) interpretation of the world. In this process, it is not only the personified other conflict party that is moralized; rather, the desire for its disappearance (for example, through conflict suppression or assimilation) becomes clear, which in turn indicates a lack of recognition of the normality of conflicts on the part of the conflict parties.

The results of the present study provide another example of the transformation of factual and procedural conflicts, as presented in the initial video, into identity and value conflicts [96,99,102]. This transformation is taking place as a result of the use of modern communication technologies at a hitherto unprecedented speed [103]. In Dahrendorf’s sense, this makes it more difficult to regulate these conflicts; a polarization occurs that increases to dichotomization. At the same time, the moralization of the conflict means, on the one hand, the mobilization of the members of one’s own conflict party, and, on the other hand, one’s own submissions to the communication. Thus, freed from the argumentative burden of factual and procedural questions, utopias can be used without any worries as standards of comparison for current social situations.

Against the background of the current state of the scientific debate on conflicts in the context of strategies to deal with climate change (for instance, at [5,104,105,106,107,108,109,110]), the empirical findings obtained here can be categorized in light of Ralf Dahrendorf’s conflict theory as follows: The high degree of moralization means the exaggeration of one’s own worldview, and the formation of the other ‘quasi-group’ (phase 1) is accordingly stigmatized as not legitimate. The awareness of alternative interests takes place under their pathologization (phase 2). The manifestation of the openly visible conflict (phase 3) accordingly cannot result in an effort to find a settlement acceptable to both sides. This fails not least because the principle of moralization is based on discrediting and pathologizing. The legitimacy of the other party to the conflict cannot possibly be regarded as legitimate. However, as the study has shown, the conflict over how to deal with climate change has reached a state that goes beyond the framework of dealing with social conflicts stretched by Dahrendorf and fundamentally calls into question the possibility of settling the conflict. There is neither a social consensus on the framework in which conflicts are to be dealt with, nor on a basic set of what is to be regarded as ‘real’ [111].

9. Conclusions

In the sense of Ralf Dahrendorf, conflicts played out by means of moralization—this study provides a current example—can be outlined as negative-productive. The transformation of factual and procedural conflicts into morally charged identity and worldview conflicts can be understood as an expression of a “new search for homogeneity” [79] (p. 9), connected with the desire of numerous people “to live among their own kind” [79] (p. 9). This, in turn, is related to the “suppression of minorities internally and artificial demarcation externally. Put less innocuously, civil war and war often follow from the false god of the homogeneous nation” [79] (p. 9). The irony of such utopian striving for harmony lies not least in the fact that the measures of moralization taken to achieve it have the opposite effect of what they want to achieve: a “release of aggressions” [112] (p. 35) which become all the greater the more intensive the attempts to suppress social conflicts, precisely through moralization. The two dominant utopias, which become recognizable from the comments, stand thereby in exclusivist and incommensurable interpretation sovereignty competition. On the one hand stands the utopia of a harmonious unity of humans and nature, coined by climatic neutrality, regional economy, vegan nutrition, living in a community of the like-minded (beyond the nuclear family) in multi-unit houses in rather urban spatial contexts, etc. On the other hand stands the utopia of satisfying individual (material) needs in an otherwise stable material-spatial and legal framework in scattered settlements. Politically, these utopias can no longer be classified in the classic right-left scheme; for example, the first utopia, with its strong pressure on the individual to conform to communal norms, also contains conservative elements, while the classic socialist approach to emancipation from social ties is hardly relevant anymore. The second utopia, on the other hand, combines the conservative desire for stability with libertarian elements of self-empowerment (cf. in this context: [113,114,115,116,117,118,119]). The position of science is instrumental in both utopias: In the first case, affirmative, yet selective with respect to certain earth system sciences, and scientifistic, with the basis of sciences, doubt and the diversity of theories and methods, left out. In the context of the second utopia, science is framed as one of many alternative interpretations of the world, which, moreover, is always under establishment suspicion (more detailed: [96,120,121,122,123]).

In this context, productive conflict resolution is hampered to the point of impossibility. This ranges from the non-recognition of the normality of conflicts, to the moral pathologization of the other conflict party, to a barely existing consensus on what is recognized as ‘true’ (even if only ‘viable’) and how fundamentally societal conflicts should be negotiated. Thus, there is also a lack of an arena for negotiating the underlying conflict over questions of how to deal with the consequences of climate change that do justice to the politically aroused hopes for participation in the design for mitigation and adaptation in relation to climate change, against the background of balancing constraints on current individual lifestyles against generalized expectations of preserving life chances for future generations [121,124,125]. In this respect, the discussion forums for reporting on current events (in this case a flood disaster) are merely an outlet for releasing individual or conflict group-specific moral overpressure, with no or minimal chance of (political) effectiveness. Here, the Janus-faced nature of social media also becomes clear, using the July flood in West Germany as an example: on the one hand, they enable the coordination of a large number of individual offers of support; on the other hand, they represent the central medium for increasing the destructiveness of social conflicts—here, using the flood.

Less pessimistic is the reflection of the ‘neopragmatic’ framework of the present study. The two theoretical frameworks have proven to be complementary and have demonstrated their potential to contribute to the explanation of the complex subject of mass-media-mediated and -intensified conflicts. The triangulation of methods has also yielded results that could not have been achieved with only one method (for example, without inductively qualitative categories, deductive categorization, in all likelihood less appropriate to the topic, would have characterized the quantitative study). The researchers’ triangulation produced different perspectives (specifically on how digital social media works), and the data triangulation in turn served to corroborate the findings of the exploratory study. This explorative study has clarified the potential of a neopragmatic approach to media content, but it has also shown that there is still a great potential for differentiation, for example, with regard to the negotiation of the topic of the July flood in media contexts that are not primarily German-language or with regard to different digital social media, but also in the comparison between these and analog media. Here, further differentiated insights into the social construction of anthropogenic climate change and, in particular, how to deal with it and the accompanying moral polarization could be achieved. Our article aims to contribute to the disclosure of the harmfulness of closed discourses. Moral polarization can only be prevented if society succeeds in breaking up monardization into closed discourses. Moralization (here in the sense of Douglas’ blaming theory [55]) supports the cohesion of society when there is a unified moral foundation. If there is not, it contributes to monardization into different sub-societies [60,64,121,125]. Without such an opening of discourses, a constructive approach to the challenges of reducing anthropogenic climate change and dealing with its consequences will not be possible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.K., L.K. and M.-L.Z.; methodology, L.K. and M.-L.Z.; theoretical framework, O.K.; investigation, M.-L.Z. and L.K.; writing and review, O.K., M.-L.Z., L.K. and G.S.; visualization, G.S., M.-L.Z. and L.K. All authors contributed jointly to prepare the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Tübingen. The research, however, received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All analyzed comments are publicly available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kInnbKht5bA (accessed on 12 October 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weber, F.; Jenal, C.; Roßmeier, A.; Kühne, O. Conflicts around Germany’s Energiewende: Discourse patterns of citizens‘ initiatives. Quaest. Geogr. 2017, 36, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weber, F. Konflikte um die Energiewende: Vom Diskurs zur Praxis; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leibenath, M.; Otto, A. Competing Wind Energy Discourses, Contested Landscapes. Landsc. Online 2014, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenath, M. Raumplanung im Spannungsfeld von Verrechtlichung und Bürgerprotest: Das Beispiel Windenergie in der Planungsregion Oberes Elbtal/Osterzgebirge. In Architektur- und Planungsethik: Zugänge, Perspektiven, Standpunkte; Berr, K., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 33–45. ISBN 978-3-658-14972-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kamlage, J.-H.; Drewing, E.; Reinermann, J.L.; de Vries, N.; Flores, M. Fighting fruitfully? Participation and conflict in the context of electricity grid extension in Germany. Util. Policy 2020, 64, 101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, O.; Weber, F.; Berr, K. The productive potential and limits of landscape conflicts in light of Ralf Dahrendorf‘s conflict theory. Soc. Mutam. Politica 2019, 10, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, K. Die Akzeptanz des Stromnetzausbaus—Eine Interdisziplinäre Untersuchung der Möglichkeiten und Grenzen gesetzlicher Regelungen zur Akzeptanzsteigerung Entlang des Verfahrens für Einen Beschleunigten Stromnetzausbau nach dem EnWG und dem NABEG; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2020; ISBN 3848766191. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, S.; Schwarz, L. The Energy Transition from Plant Operators’ Perspective—A Behaviorist Approach. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bues, A.; Gailing, L. Energy Transitions and Power: Between Governmentality and Depoliticization. In Conceptualizing Germany’s Energy Transition: Institutions, Materiality, Power, Space; Gailing, L., Moss, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 69–91. ISBN 978-1-137-50592-7. [Google Scholar]

- Weingart, P.; Engels, A.; Pansegrau, P. Von der Hypothese zur Katastrophe: Der anthropogene Klimawandel im Diskurs zwischen Wissenschaft, Politik und Massenmedien, 2nd ed.; Leicht Veränderte Auflage; Barbara Budrich: Opladen, Germany; Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2008; ISBN 3866491344. [Google Scholar]

- Weingart, P. Kassandrarufe und Klimawandel. Gegenworte 2002, 10, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Joas, H. Symbolischer Interaktionismus: Von der Philosophie des Pragmatismus zu einer soziologischen Forschungstradition. Kölner Z. Für Soziologie Und Soz. 1988, 40, 417–446. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, H.-J.; Joas, H.; Wenzel, H. Pragmatismus zur Einführung: Kreativität, Handlung, Deduktion, Induktion, Abduktion, Chicago School, Sozialreform, symbolische Interaktion; Junius Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 3885066823. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, C. Pragmatismus—Umwelt—Raum: Potenziale des Pragmatismus für eine Transdisziplinäre Geographie der Mitwelt; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9783515108829. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, C. Von Interaktion zu Transaktion–Konsequenzen eines pragmatischen Mensch-Umwelt-Verständnisses für eine Geographie der Mitwelt. Geogr. Helv. 2014, 69, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorty, R. Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; ISBN 0521353696. [Google Scholar]

- Rorty, R. Consequences of Pragmatism: Essays: 1972–1980; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1982; ISBN 0816610649. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, H. Pragmatism: An Open Question; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, D.L. The neopragmatist turn. Southwest Philos. Rev. 2003, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, D.L. Pragmatism, neopragmatism, and public administration. Adm. Soc. 2005, 37, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warms, C.A.; Schroeder, C.A. Bridging the gulf between science and action: The “new fuzzies” of neopragmatism. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1999, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichhart, P. Auf der Suche nach der “dritten Säule”. Gibt es Wege von der Rhetorik zur Pragmatik? In Möglichkeiten und Grenzen integrativer Forschungsansätze in Physischer Geographie und Humangeographie; Müller-Mahn, D., Wardenga, U., Eds.; Selbstverlag Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde e.V.: Leipzig, Germany, 2005; pp. 109–136. ISBN 3860820532. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, C. Materie oder Geist? Überlegungen zur Überwindung dualistischer Erkenntniskonzepte aus der Perspektive einer Pragmatischen Geographie. Ber. Zur Dtsch. Landeskd. 2009, 83, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kersting, P. Geomorphologie, Pragmatismus und integrative Ansätze in der Geographie. Ber. Zur Dtsch. Landeskd. 2012, 86, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, F. Spatial Complexity: Theory, Mathematical Methods and Applications; Springer Nature: Cham, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783030596712. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, F. Modelling and Visualization of Landscape Complexity with Braid Topology. In Modern Approaches to the Visualization of Landscapes; Edler, D., Jenal, C., Kühne, O., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, A. Der Blickpunkt von niemand besonderen. In Die Renaissance des Pragmatismus: Aktuelle Verflechtungen zwischen analytischer und kontinentaler Philosophie; Sandbothe, M., Ed.; Velbrück: Weilerswist, Germany, 2000; pp. 59–77. ISBN 9783934730243. [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt, F. Stadtforschung: Gegenstand und Methoden; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9783658008239. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Jenal, C. Neopragmatische Regionale Geographien—Eine Annäherung. In Louisiana—Mediengeographische Beiträge zu Einer Neopragmatischen Regionalen Geographie; Kühne, O., Sedelmeier, T., Jenal, C., Eds.; Springer (im Druck): Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Reboot “Regionale Geographie”—Ansätze einer neopragmatischen Rekonfiguration “horizontaler Geographien”. Berichte. Geogr. Und Landeskd. 2018, 92, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M. Approaches to Qualitative-Quantitative Methodological Triangulation. Nurs. Res. 1991, 40, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flick, U. Triangulation; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; ISBN 9783531181257. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Triangulation in Data Collection. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018; pp. 527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Ritzer, G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M. (Ed.) Rorty Lesen; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Landscape Theories: A Brief Introduction; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rorty, R. Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Reprint; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; ISBN 9780521353816. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Jenal, C. Baton Rouge—A Neopragmatic Regional Geographic Approach. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, O. Contours of a ‘Post-Critical’ Cartography—A Contribution to the Dissemination of Sociological Cartographic Research. KN—J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2021, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L. Unwetter in der Eifel: Die Faktoren Hinter den Vernichtenden Sturzfluten. Available online: https://www.spektrum.de/news/unwetter-die-faktoren-hinter-den-vernichtenden-sturzfluten/1895908 (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Landesamt für Umwelt Rheinland-Pfalz. Übersicht des Pegels Altenahr. Available online: https://www.hochwasser-rlp.de/karte/einzelpegel/flussgebiet/rhein/teilgebiet/mittelrhein/pegel/ALTENAHR (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Peters, G. Mönchengladbach prüft die Rückkehr der Alarmsirenen. Westdeutsche Zeitung [Online], March 2, 2015. Available online: https://www.wz.de/nrw/moenchengladbach/moenchengladbach-prueft-die-rueckkehr-der-alarmsirenen_aid-29256433 (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Skowronek, M.; Stephanowitz, J. Flutkatastrophe: Keine Vermissten mehr nach Hochwasser in NRW. zeit online [Online], July 28, 2021. Available online: https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2021-07/flutkatastrophe-nrw-keine-vermissten-herbert-reul-landtag-hochwasser-todesopfer (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Westdeutscher Rundfunk. Flut. Available online: https://www1.wdr.de/suche/index.jsp?q=flut (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Junghänel, T.; Bissolli, P.; Daßler, J.; Fleckenstein, R.; Imbery, F.; Janssen, W.; Kaspar, F.; Lengfeld, K.; Leppelt, T.; Rauthe, M.; et al. Hydro-klimatologische Einordnung der Stark- und Dauerniederschläge in Teilen Deutschlands im Zusammenhang mit dem Tiefdruckgebiet „Bernd“ vom 12. bis 19. Juli 2021. Available online: https://www.dwd.de/DE/leistungen/besondereereignisse/niederschlag/20210721_bericht_starkniederschlaege_tief_bernd.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6 (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Statista (2021): Zuschauermarktanteile der Tv-Sender im September 2021. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/75044/umfrage/zuschauermarktanteile-der-tv-sender-monatszahlen/ (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Wildfeuer, A.G. Wert. In Neues Handbuch philosophischer Grundbegriffe; Kolmer, P., Wildfeuer, A.G., Eds.; Alber: Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 2011; pp. 2484–2504. ISBN 9783495482223. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckhohn, C. Values and value-orientation in the theory of action: An exploration in definition and classification. In Toward a General Theory of Action; Parsons, T., Shils, E.A., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1951; pp. 388–433. ISBN 9780674863507. [Google Scholar]

- Hubig, C. Handlung—Identität—Verstehen: Von der Handlungstheorie zur Geisteswissenschaft; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1985; ISBN 3407546874. [Google Scholar]

- Grau, A. Hypermoral: Die neue Lust an der Empörung, 2nd ed.; Claudius: München, Germany, 2017; ISBN 9783532628034. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, N. Ethik; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Leipzig, Germany, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, C. Die Tyrannei der Werte, 3rd ed.; Duncker & Humblot: Berlin, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-428-83457-0. [Google Scholar]

- Berr, K. Zum ethischen Gehalt des Gebauten und Gestalteten. Ausdruck Und Gebrauch—Dresdner Wiss. Halbjahreshefte Archit. Wohn. Umw. 2014, 12, 30–56. [Google Scholar]

- Berr, K. Zur Moral des Bauens, Wohnens und Gebauten. In Architektur- und Planungsethik: Zugänge, Perspektiven, Standpunkte; Berr, K., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 111–138. ISBN 978-3-658-14972-7. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Risk and Blame; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Systemtheorie der Gesellschaft; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2017; ISBN 9783518587058. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, C. Das befremdliche Überleben des Neoliberalismus: Postdemokratie II; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-518-42274-8. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Die Realität der Massenmedien; Westdeutscher: Opladen, Germany, 1996; ISBN 3-531-12841-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, T. Die Vereindeutigung der Welt: Über den Verlust an Mehrdeutigkeit und Vielfalt, 3rd ed.; Reclam: Ditzingen, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783150194928. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Die Moral des Risikos und das Risiko der Moral. In Risiko und Gesellschaft: Grundlagen und Ergebnisse interdisziplinärer Risikoforschung; Bechmann, G., Ed.; Westdeutscher: Opladen, Germany, 1993; pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, U. Das Schweigen der Mitte: Wege aus der Polarisierungsfalle; WBG: Darmstadt, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3806240573.

- Lübbe, H. Politischer Moralismus: Der Triumph der Gesinnung über die Urteilskraft; LIT: Berlin, Germany; Münster, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3643143006. [Google Scholar]

- Haus, M. Kommunitarismus: Einführung und Analyse; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2003; ISBN 9783531136622. [Google Scholar]

- Stegemann, B. Die Moralfalle: Für eine Befreiung linker Politik; Matthes & Seitz: Berlin, Germany, 2018; ISBN 3-95757-712-8. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Gesellschaftsstruktur und Semantik: Studien zur Wissenssoziologie der modernen Gesellschaft; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt (Main), Germany, 1989; ISBN 3518579487. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, A. Moralische Expertise? Zur Produktionsweise von Kommissionsethik. In Wozu Experten? Ambivalenzen der Beziehung von Wissenschaft und Politik; Bogner, A., Torgersen, H., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; pp. 172–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. The Social Construction of Space and Landscape in Internet Videos. In Modern Approaches to the Visualization of Landscapes; Edler, D., Jenal, C., Kühne, O., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pariser, E. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781594203008. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J. Representations of ‘trolls’ in mass media communication: A review of media-texts and moral panics relating to ‘internet trolling’. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2014, 10, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E. Intimisierte Öffenlichkeiten: Zur Erzeugung von Publika auf Facebook. In Praktiken der Überwachten: Öffentlichkeit und Privatheit im Web 2.0; Stempfhuber, M., Wagner, E., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 243–266. ISBN 9783658117191. [Google Scholar]

- Nagle, A. Kill All Normies: The Online Culture Wars from Tumblr and 4chan to the Alt-Right and Trump; Zero Books: Winchester, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-78535-543-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Weber, F. Der Energienetzausbau in Internetvideos—eine quantitativ ausgerichtete diskurstheoretisch orientierte Analyse. In Landschaftswandel—Wandel von Machtstrukturen; Kost, S., Schönwald, A., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; pp. 113–126. ISBN 978-3-658-04330-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Stadt—Landschaft—Hybridität: Ästhetische Bezüge im postmodernen Los Angeles mit seinen modernen Persistenzen; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-531-18661-0. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, F.; Kühne, O. Räume unter Strom: Eine diskurstheoretische Analyse zu Aushandlungsprozessen im Zuge des Stromnetzausbaus. Raumforsch. Und Raumordn. —Spat. Res. Plan. 2016, 74, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ash, T.G. Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9780300161168. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Soziale Klassen und Klassenkonflikt in der industriellen Gesellschaft; Enke: Stuttgart, Germany, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Sozialer Konflikt. In Wörterbuch der Soziologie; Bernsdorf, W., Ed.; Ferdinand Enke: Stuttgart, Germany, 1969; pp. 1006–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Konflikt und Freiheit: Auf dem Weg zur Dienstklassengesellschaft; Piper: München, Germany, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Der moderne soziale Konflikt: Essay zur Politik der Freiheit; Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt DVA: Stuttgart, Germany, 1992; ISBN 3-421-06539-X. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Die Krisen der Demokratie: Ein Gespräch mit Antonio Polito; C.H. Beck: München, Germany, 2003; ISBN 978-3406494604. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Versuchungen der Unfreiheit: Die Intellektuellen in Zeiten der Prüfung; C.H. Beck: München, Germany, 2008; ISBN 9783406573781. [Google Scholar]

- Niedenzu, H.-J. Konflikttheorie: Ralf Dahrendorf. In Soziologische Theorie: Abriß der Ansätze ihrer Hauptvertreter, 5th ed.; Morel, J., Bauer, E., Meleghy, T., Niedenzu, H.-J., Preglau, M., Staubmann, H., Eds.; Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag: München, Germany; Wien, Austria, 1997; pp. 171–189. ISBN 3486239953. [Google Scholar]