A Systematic Review on Adaptation Practices in Aquaculture towards Climate Change Impacts

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Need for a Systematic Literature Review Related to Adaptation Practices among Aquaculture Communities

2. Materials and Methods

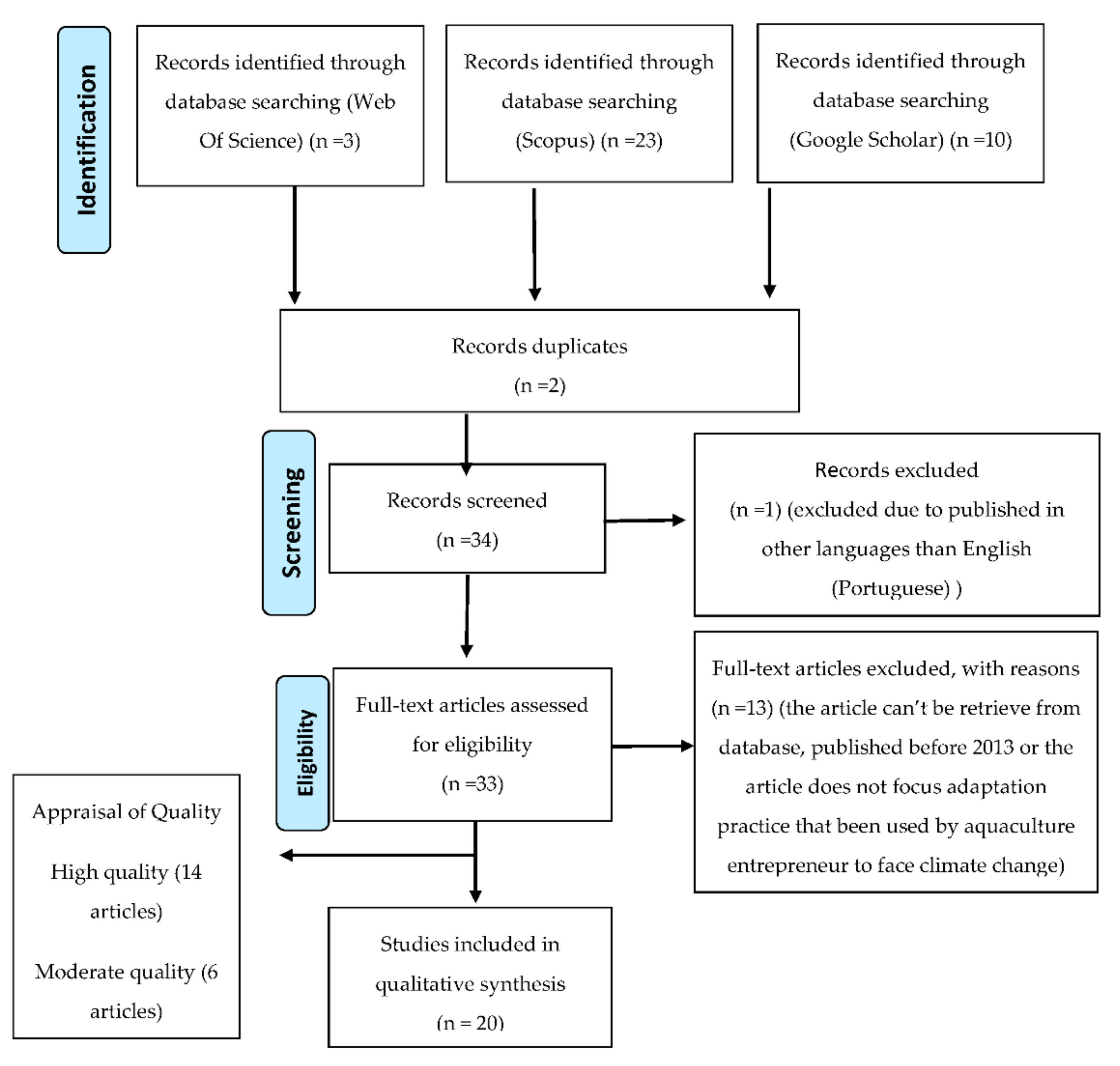

2.1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

2.2. Formulation of Research Questions

2.3. Systematic Searching Strategy

2.3.1. Identification

2.3.2. Screening

2.3.3. Eligibility

2.4. Appraisal of Quality

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Background of The Selected Studies

3.2. Adaptation Practices Exercised by Aquaculture Community to Face Climate Change Impacts

3.2.1. Governmental

Product Market (PM)

Standard Policy and Management (SP)

Capacity Training (CT)

Associations’ Cooperation (AC)

Strengthened Relationship (SR)

3.2.2. Community

Spread Risk Information (SI)

Monitoring Rotation System (MR)

Women’s Participation/Family Members’ Participation (WP)

3.2.3. Facilities

Change of Diet (CD)

Cage Management (CM)

Warning Systems (WS)

Technology Management (TM)

Natural Barriers (NB)

3.2.4. Temperature

Temperature Tolerant Strains (TS)

Seasonal Data Monitoring (SD)

3.2.5. Financial

Financial Access (FA)

Government Support (GS)

Job/Livelihood Diversity (JD)

4. Discussion

5. What Next?

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018—Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i9553en/i9553en.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Sustainability in Action. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/ca9229en.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Barange, M. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018: Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. 2018. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i9540en/i9540en.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Hanson, S.; Nicholls, R.; Ranger, N.; Hallegatte, S.; Corfee-Morlot, J.; Herweijer, C.; Chateau, J. A global ranking of port cities with high exposure to climate extremes. Clim. Chang. 2011, 104, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azra, M.N.; Aaqillah-Amr, M.A.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H.; Waiko, K.; Otrensky, A.; Tavares, C.P.D.S.; Abol-Munafi, A.B. Effects of climate-induced water temperature changes on the life history of brachyuran crabs. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Wahab, M.A. Impact of Climate Change on Shrimp Farming in the South-West Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Res. Agric. Livest. Fish. 2016, 3, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, T.B.; Shrestha, M.K.; Bhujel, R.C.; Pradhan, N.; Swar, D.B.; Pandit, N.; Rai, S.; Wagle, S.K. Aquaculture diversification for sustainable livelihood in Nepal. Nepal. J. Aquac. Fish. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffril, H.; Abu Samah, A.; D’Silva, J.L. Adapting towards climate change impacts: Strategies for small-scale fishermen in Malaysia. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Silva, J.L.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Samah, B.A.; Uli, J. Assessment of social adaptation capacity of Malaysian fishermen to climate change. J. Appl. Sci. 2012, 12, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramli, S.A.; Abu Samah, A.; Shaffril, H.A.M. Examining factors affecting change adaptation practice among small-scale fishermen in Kelantan and Pulau Pinang. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bukvic, A.; Gohlke, J.; Borate, A.; Suggs, J. Aging in Flood-Prone Coastal Areas: Discerning the Health and Well-Being Risk for Older Residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samah, A.A.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Fadzil, M.F. Comparing adaptation ability towards climate change impacts between the youth and the older fishermen. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 681, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Abu Samah, A.; Idris, K.; Abu Samah, B.; Hamdan, M.E. The adaptation towards climate change impacts among islanders in Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, W.J.; Hai Hanh, T.T. Adaptation to climate change as social–ecological trap: A case study of fishing and aquaculture in the Tam Giang Lagoon, Vietnam. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1527–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, L.; Hjøllob, S.S.; Telfera, T.C.; McAdama, B.J.; Hermansenc, O.; Ytteborgc, E. The importance of calibrating climate change projections to local conditions at aquaculture sites. Aquaculture 2019, 514, 7334487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, L.C.; Kochalski, S.; Aguirre-Velarde, A.; Vivar, I.; Wolff, M. Coping with abrupt environmental change: The impact of the coastal El Ni~no 2017 on artisanal fisheries and mariculture in North Peru. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 76, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K. Impact of climate change: A curse to the shrimp farming in India. Int. J. Adv. Res. Ideas Innov. Technol. 2018, 4, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M.E. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Krauss, S.E.; Samsuddin, S.F. A systematic review on Asian’s farmers’ adaptation practices towards climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Abu Samah, A. The ABC of systematic literature review: The basic methodological guidance for beginners. Qual. Quant. 2021, 55, 1319–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Legese, G. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Idris, K.; Abu Samah, A.; Samsuddin, S. F Guidelines for developing a systematic literature review for studies related to climate change adaptation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 22265–22277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Dasí-Rodríguez, S. The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1023–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.A. Methodological Guidance Paper: The Art and Science of Quality Systematic Reviews. Rev. Educ. Res. 2020, 90, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, K.; Booth, A.; Garside, R.; Tunçalp, O.; Noyes, J. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: Clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Glob. Health 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormedal, I. Corporate Strategies in Environmental Governance: Marine harvest and regulatory change for sustainable aquaculture. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, R.; Kari, F.; Othman, A. Biophysical Vulnerability Impact Assessment of Climate Change on Aquaculture Sector Development in Sarawak, Malaysia. DLSU Bus. Econ. Rev. 2015, 24, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, K.; Mohamed Shaffril, H.A.; D’Silva, J.L.; Man, N. Identifying Problems among Seabass Brackish-Water Cage Entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biju Kumar, A.; Bhagyalekshmi, V.; Riyas, A. Climate change, fisheries and coastal ecosystems in India. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2017, 5, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, S.K.; Trivedi, R.K.; Chand, B.K.; Mandal, B.; Rout, S.K. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change, impacts on freshwater aquaculture and adaptation strategies in climatic change hotspots: A case of the Indian Sundarban delta. Environ. Dev. 2017, 21, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Ahmed, M.; Ojea, E.; Fernandes, J.A. Impacts and responses to environmental change in coastal livelihoods of south-west Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637–638, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.A.; Akber, M.A.; Ahmed, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M.R. Climate change adaptations of shrimp farmers: A case study from southwest coastal Bangladesh. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameem, M.I.M.; Momtaz, S.; Kiem, A.S. Local perceptions of and adaptation to climate variability and change: The case of shrimp farming communities in the coastal region of Bangladesh. Clim. Chang. 2015, 133, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Bunting, S.W.; Rahman, S.; Garforth, C.J. Community-based climate change adaptation strategies for integrated prawn–fish–rice farming in Bangladesh to promote social–ecological resilience. Rev. Aquac. 2014, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, O.M.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Klerkx, L. Are shrimp farmers actual gamblers? An analysis of risk perception and risk management behaviors among shrimp farmers in the Mekong Delta. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, P.; Whangchai, N.; Chitmanat, C.; Lebel, L. Climate risk management in river-based tilapia cage culture in northern Thailand. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 7, 476–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navy, H.; Minh, T.H.; Pomeroy, R. Impacts of climate change on snakehead fish value chains in the Lower Mekong Basin of Cambodia and Vietnam. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2017, 21, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, N.; Edwin, L.; Meenakumari, B. Transformation in gender roles with changes in traditional fisheries in Kerala, India. Asian Fish. Sci. Spec. Issue 2014, 27S, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, N.; Andre, J.; Charef, A.; Damalas, D.; Green, B.; Parker, R.; Sumaila, R.; Thomas, G.; Tobi, R.; Watson, R. Energy prices and seafood security. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; D’Silva, J.L.; Kamaruddin, N.; Omar, S.Z.; Bolong, J. The coastal community awareness towards the climate change in Malaysia. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 7, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.Z.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Bolong, J.; D’Silva, J.L.; Abu Hassan, M. Usage of offshore ICT among fishermen in Malaysia. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 3–4, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Mazuki, R.; Omar, S.Z.; Bolong, J.; D’Silva, J.L.; Hassan, M.A.; Shaffril, H.A.M. Social influence in using ICT among fishermen in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.; McIvor, A.; Tonneijck, F.H.; Tol, S.; van Eijk, P. Mangroves for coastal defence. In Guidelines for Coastal Managers & Policy Makers; Wetlands International and The Nature Conservancy: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty P, Honnery D Energy Efficiency or Conservation for Mitigating Climate Change? Energy 2019, 12, 3543. [CrossRef]

- Duarah, J.P.; Mall, M. Diversified fish farming for sustainable livelihood: A case-based study on small and marginal fish farmers in Cachar district of Assam, India. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, A.S. Adapting to environmental change in artisanal fisheries—Insights from a South Indian Lagoon. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barange, M.; Bahri, T.; Beveridge, M.C.M.; Cochrane, K.L.; Funge-Smith, S.; Poulain, F. Impacts of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture: Synthesis of current knowledge, adaptation and mitigation options. FAO Fish. Aquac. Tech. 2018, 628, 627. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation Women Watch Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change. 2009. Available online: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Khalil, M.B.; Jacobs, B.C.; McKenna, K.; Kuruppu, N. Female contribution to grassroots innovation for climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Clim. Dev. 2020, 12, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Databases | Keywords Used |

|---|---|

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“climate* chang*” OR “climate* risk*” OR “climate* variabilit*” OR “climate* extreme*” OR “climat* uncertaint*” OR “global warming*” OR “temperature rise*” OR “sea level rise*” OR “el-nino” OR “la-nina” OR “el nino” OR “la nina”) AND (“adapt* abilit*” OR “adapt* strateg*” OR “adapt* capacit*” OR “adapt* capabilit*” OR “adapt* strength*” OR “adapt* potential*” OR “adopt* abilit*” OR “adopt* strateg*” OR “adopt* capacity*” OR “adopt* capabilit*” OR “adopt* strength” OR “adopt* potential*”) AND (“aquacultur*” OR “hydroponic* cultur*” OR “hydro* ponic* aquacultur*” OR “tray* agricultur*”) AND (“entrepreneur*” OR “contractor*” OR “producer*” OR “business person*” OR “impresario*” OR “industrialist*”)) |

| WEB OF SCIENCE | TS = ((“climate* chang*” OR “climate* risk*” OR “climate* variabilit*” OR “climate* extreme*” OR “climat* uncertaint*” OR “global warming*” OR “temperature rise*” OR “sea level rise*” OR “el-nino” OR “la-nina” OR “el nino” OR “la nina”) AND (“adapt* abilit*” OR “adapt* strateg*” OR “adapt* capacit*” OR “adapt* capabilit*” OR “adapt* strength*” OR “adapt* potential*” OR “adopt* abilit*” OR “adopt* strateg*” OR “adopt* capacity*” OR “adopt* capabilit*” OR “adopt* strength” OR “adopt* potential*”) AND (“aquacultur*” OR “hydroponic* cultur*” OR “hydro* ponic* aquacultur*” OR “tray* agricultur*”) AND (“entrepreneur*” OR “contractor*” OR “producer*” OR “business person*” OR “impresario*” OR “industrialist*”)) |

| Criterion | Eligibility | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Literature type | Journal (research articles) | Journals (systematic review), book series, book, chapter in book, conference proceeding |

| Language | English | Non-English |

| Timeline | Between 2013 and 2020 | 2012 and earlier |

| MAIN STUDY DESIGN | Governmental | Community | Facilities | Temperature | Financial | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTHOR/COUNTRIES | PM | SP | CT | AC | SR | SI | MR | WP | CD | CM | WS | TM | NB | TS | SD | FA | GS | JD | |

| Falconer et al. (2020)—Norway | QN | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Kluger et al. (2019)—Peru | QN | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Pelletier et al. (2014)—62 Developing Countries | QN | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Hamdan et al. (2015)—Malaysia | QN | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Idris et al. (2013)—Malaysia | QL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mohanty (2018)—India | QL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Islam et al. (2016)—Bangladesh | MM | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Ahmed et al. (2014)—Bangladesh | QL | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Vormedal (2017)—Norway | QL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Gopal et al. (2014)—United Nations | QL | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Boonstra & Hai Hanh (2015)—Vietnam | MM | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Gurung et al. (2018)—Nepal | QL | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Biju Kumar et al. (2017)—India | QL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Dubey et al. (2017) | MX | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Hossain et al. (2018) | MX | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Islam et al. (2019) | MX | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Joffre et al. (2018) | QN | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Lebels et al. (2015) | MX | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Navy et al. (2017) | QN | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Shameem et al. (2015) | MX | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| GOVERNMENTAL | COMMUNITY | FACILITIES | TEMPERATURE | FINANCIAL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM | Products Markets | SI | Spread Risk Information | CD | Change of Diet | TS | Temperature Tolerant Strains | FA | Financial Access |

| SP | Standard Policy and Management | MR | Monitoring Rotation System | CM | Cage Management | SD | Seasonal Data Monitoring | GS | Government Support |

| CT | Capacity Training | WP | Women/family members Participation | WS | Warning System | PC | Price Control | ||

| AC | Associations Cooperation | TM | Technology Management | JD | Job Diversity | ||||

| SR | Strengthened Relationship | NB | Natural Barriers | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abu Samah, A.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Fadzil, M.F.; Ahmad, N.; Idris, K. A Systematic Review on Adaptation Practices in Aquaculture towards Climate Change Impacts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011410

Abu Samah A, Shaffril HAM, Fadzil MF, Ahmad N, Idris K. A Systematic Review on Adaptation Practices in Aquaculture towards Climate Change Impacts. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011410

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbu Samah, Asnarulkhadi, Hayrol Azril Mohamed Shaffril, Mohd Fauzi Fadzil, Nobaya Ahmad, and Khairuddin Idris. 2021. "A Systematic Review on Adaptation Practices in Aquaculture towards Climate Change Impacts" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011410

APA StyleAbu Samah, A., Shaffril, H. A. M., Fadzil, M. F., Ahmad, N., & Idris, K. (2021). A Systematic Review on Adaptation Practices in Aquaculture towards Climate Change Impacts. Sustainability, 13(20), 11410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011410