Abstract

Sado Island in the Niigata prefecture is among the first Globally Important Agriculture Heritage Systems (GIAHSs) in Japan and among developed countries worldwide. Recent studies have pointed out the need to incorporate culture and farmer opinions to further strengthen GIAHS inclusivity in rural farming. In connection to this, this study explored whether farmer visibility, which is highlighted by GIAHS designation, actually translates to farmers’ actual perceptions of GIAHS involvement. A survey was conducted among Sado Island farmers to determine their knowledge and perception of their GIAHS involvement, in connection to their perspectives on youth involvement, Sado Island branding, and tourism management. Results showed that 56.3% of Sado Island farmers feel uninvolved or unsure towards the GIAHS, which is in stark contrast with the prevalent farming method in the area, special farming (which complies with GIAHS regulations) (77.3%). Further analyses revealed that farmers who feel that the GIAHS does not promote youth involvement, Sado Island branding, and tourism management have a higher predisposition to perceive themselves as uninvolved towards the GIAHS. This study highlights the need for careful reevaluation and integration of farmer insights and needs into the current GIAHS implementation in Sado Island and in other GIAHSs as well.

1. Introduction

In 2002, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) first launched the Globally Important Agriculture Heritage System (GIAHS) Program during the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa. This is part of the Global Partnership Initiative which aims to tackle issues such as sustainable development, agriculture, and traditional farming practices [1]. In 2015, it became a corporate program of the FAO which was further developed to protect traditional agricultural systems of global importance and enhance the harmonious relationship between people and nature. Specifically, the FAO defines the GIAHS in 2002 as “remarkable land use systems and landscapes which are rich in globally significant biological diversity evolving from the co-adaptation of a community with its environment and its needs and aspirations for sustainable development” [2] (p. 1). The selection criteria to be designated as a GIAHS are: (1) food and livelihood security; (2) agrobiodiversity; (3) traditional knowledge; (4) cultures and social values; and (5) landscape features. Overall, the object of designation is an agricultural system composed of traditional knowledge and practices, landscapes, culture, and biodiversity [3]. Since 2005, the FAO has designated 62 systems in 22 countries and is currently reviewing 15 proposals from eight new countries. These selected sites worldwide provide food and livelihood security for millions of small-scale farmers, as well as sustainably produced goods and services. Furthermore, they contribute to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by bringing together economic, social, and environmental dimensions [1].

The overall objective of designating a GIAHS site is to highlight unique knowledge, practices, and landscapes, as well as supporting dynamic conservation of a site. The conservation of GIAHS sites is also highly advocated, entailing several developmental interventions, such as agritourism activities, adding value to GIAHS food products, technology transfer measures, awareness-raising campaigns, and supportive national policies [3]. It is important to note that designating different sites as GIAHSs can also increase awareness and visibility for farmers who are working in these areas and emphasize the critical role they play in global issues. According to the FAO, the backbone of many GIAHS sites are the small-scale and family farmers, since they contribute to achieving food security, preserving rural knowledge, and protecting agrobiodiversity and fragile landscapes [1]. Therefore, raising farmer visibility is essential, most especially in this modern era when the field of agriculture faces a range of issues, including the declining interest of youths, outmigration from rural to urban areas, farmland abandonment, the transfer of indigenous and traditional knowledge, the prioritization of modernization movements in conflict with agricultural land decline and environmental degradation, among others [4,5,6,7,8]. Improving the image of agriculture can help address these issues, such as highlighting farmer visibility in traditional agricultural systems, which in turn can boost the status of agriculture worldwide. While increasing farmer visibility is important, it is also crucial to know if the importance of GIAHS principles actually translates to the ground level, particularly the farmers’ perceptions on their GIAHS involvement. This paper will focus on this aspect by analyzing Japanese farmers’ GIAHS inclusivity and how this may affect the GIAHS development in Sado Island. In particular, this paper aims to answer the question: Does farmer visibility, which is highlighted by the GIAHS designation, translate to farmers’ actual perceptions of GIAHS involvement?

Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHSs) in Japan and Their Impact on Farmer Involvement

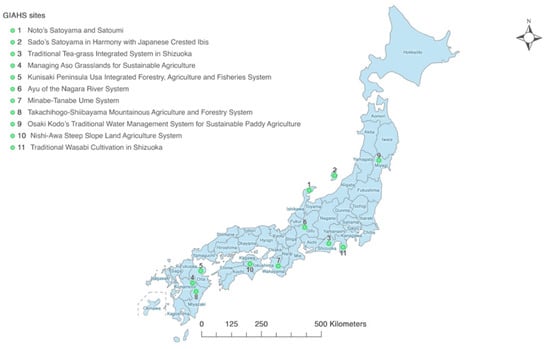

In Japan, sustainable agriculture has been promoted for several years and high importance is given in preserving traditional farming, agro-culture, and biodiversity. This led to the application and acceptance of different sites in Japan as a GIAHS. Aside from the FAO’s initial five selection criteria, Japan added three additional criteria in 2015 to have a more holistic and comprehensive assessment of the GIAHS, which are: (1) enhancing resilience (ecological); (2) establishing the participation of multiple stakeholders and promoting institutions (social); and (3) creating new business models (economic) [9]. At present, there are 11 sites designated as a GIAHS in Japan (Figure 1) [10]. All these sites have demonstrated remarkable use of land systems and landscapes, a good interplay between nature and its surrounding communities, and rich biological diversities, which all contribute to sustainable development. This paper is particularly focused on Sado Island in the Niigata prefecture, which is one of the first GIAHS sites designated in not only in Japan, but also in a developed country.

Figure 1.

Japan’s 11 designated GIAHS sites.

GIAHS sites are categorized into three major types, namely: landscape, farming method, and genetic resource conservation, of which a majority of Japanese GIAHS sites are classified as landscape types (Table 1) [11]. Out of the 11 GIAHS sites in Japan, eight, including Sado Island are classified as landscape types. Landscape type GIAHS sites comprise 33 of the 62 sites worldwide. This type of GIAHS focuses more on the interconnectedness of various landscape components, such as farmlands, rivers, irrigation canals/ponds, human settlements, among others. In Japan, this is similar to the Satoyama and Satoumi mosaic landscapes, which establish ecosystem services in connection with human well-being [12]. The three remaining GIAHS sites in Japan have a farming method classification system. There are 17 of these in the world, and they focus on the unique, traditional agricultural systems which are effective in biodiversity conservation [11]. The last one is the genetic resource conservation type, whereby traditional agricultural systems contribute to the conservation of genetic resources. There are 12 such GIAHSs in the world, but none in Japan.

Table 1.

Japan’s 11 designated GIAHS sites.

The FAO’s initiative to designate GIAHS sites worldwide is essential to address various issues in the field of agriculture. Ever since it was launched in 2002, various studies have been conducted to analyze its sustainability, characterization, the vulnerability of sites, tourism management, biodiversity conservation, among others [13,14,15,16,17]. Most studies focused more on the macro perspectives of the GIAHSs and their potential environmental impacts, which thereby established a wide-ranging knowledge on GIAHSs as a supplement to what the FAO annually provides. These studies are also very useful in crafting environmental policies which can be used to alleviate increasing ecological threats [18]. Therefore, GIAHSs are recognized for their high contribution to rural revitalization and for ensuring the fulfillment of the multifunctional roles of agriculture, such as the creation of resilient landscapes, the preservation of cultural traditions, and the conservation of the natural environment, national land, and water resources [11]. With an expansive bank of research findings, it is ideal to think that this knowledge can actually be absorbed by one of the main caretakers of GIAHS sites: the farmers. However, there are limited studies that can support this. There is still limited literature focusing on micro perspectives, such as farmer participation and perceived GIAHS involvement.

In terms of socioeconomics aspects, it was observed in [19] that livelihood endowments and strategies directly affect GIAHS farmers’ participation in eco-compensation policies. Particularly, the study found that the comprehensiveness of eco-compensation programs, land capital, and material capital are positive factors that provide farmers with incentives to participate in GIAHS conservation and agricultural production, whereas human capital was seen as a negative factor. With regards to sociocultural aspects, Kajihara et al. (2018) discussed the importance of understanding the relationship between culture and agriculture, and highlighted the need for the GIAHS criteria to incorporate culture for more effective management strategies [20]. It is important to note the interplay between farmers’ cultural perspectives and their interaction with their immediate environment, which thereby affects their involvement and mindset towards GIAHS initiatives. This, in turn, contributes to honing the overall cultural development of GIAHS sites and their sustainability. When magnified on a global scale, Sun et al. (2019) conclude that more efforts are needed to understand agricultural heritage systems by combining traditional practices and international experiences [21].

Farmer involvement and decision making can be influenced by a lot of internal and external factors [22]. Various studies have shown that farmers’ decision-making processes are being affected by critical influential factors and that they vary on a case-by-case basis [23]. In a study conducted in the Philippines which tried to measure farmers’ perspectives on a strict agricultural ban, it was found that satisfaction in the farming method used, knowledge about the main crop being grown, and personal experiences in farming are very important factors in their crop adoption decision-making process [24]. Indeed, the perception of being involved in a bigger cause is shaped by farmers’ individual differences and environmental influences. This was shown in another study conducted in the Philippines that focused on farmers’ perspectives on coexisting farming methods, which observed that groups of farmers are affected differently by internal and external factors [25]. Therefore, this enhances the need to understand farmers’ perspectives and opinions, which in turn affect their involvement in various agricultural programs. To gauge the perceived involvement of farmers in this study, it would be vital to know their opinions towards important issues related to GIAHSs. Opinions have the capacity to shape perceptions, whether in an individual or community scale. In this study, three main factors were specifically studied, and they revolved around farmers’ opinions towards the GIAHS’s effects on youth involvement, the capability to enhance agricultural products, and tourism management.

2. Study Area and Methods

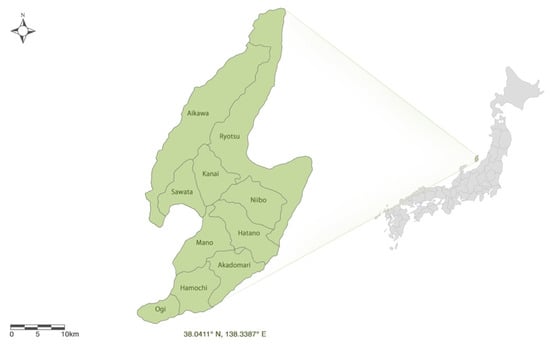

The study was conducted in Sado Island, which is located west of the Niigata prefecture shoreline (Figure 2). It is the sixth largest island in Japan, and has a complex ecosystem, with interdependent satoyama and satoumi landscapes. It is widely known as a natural habitat of endangered Japanese crested ibises (locally called Toki in Japanese) because of its satoyama and satoumi landscapes. The Japan Satoyama Satoumi Assessment (JASS) defines the former term as “landscapes that comprise a mosaic of different ecosystem types including secondary forests, agricultural lands, irrigation ponds and grasslands, along with human settlements” and the latter as “Japan’s coastal areas where human interaction over time has resulted in a high degree of productivity and biodiversity” [12] (p. 2). Sado Island is also famous for its rice produce with the Toki branding, which supports the revival of the Toki birds [26]. Other agricultural crops are also grown, such as persimmons, apples, pears, cherries, oranges, strawberries, watermelons, shiitake mushrooms, among others. Since the island provides suitable habitats for the endangered Toki birds, public and private sectors poured in efforts to support Sado Island’s biodiversity preservation through the environmental conservation agriculture (ECA) program [27], which was a huge factor in its designation as a GIAHS.

Figure 2.

Map of Sado Island.

Sado Island was selected since it is one of the first GIAHSs in Japan and because it is well supported by the local and national governments. A lot of people contribute to its development, such as the active local community, ECA-supportive consumers, and the research community, who all value the protection of Toki birds. Sado Island is a vulnerable rural region affected regularly by natural disasters, which cause crop failures and livelihood insecurity. One way to alleviate these problems are the Toki bird conservation efforts, which led to the production of certified rice, branded as Tokimai in 2008. It is marketed with a premium price and a portion of the income goes towards to conservation of the Toki birds [27]. This rice is produced in ECA lands which the Toki birds use as feeding grounds throughout the year. Sado Island is a GIAHS where people and Toki birds (wildlife) are living together in harmony. These characteristics of Sado Island warrant conducting research with the objectives mentioned above.

A questionnaire survey method was employed to collect data from ECA farmers in Sado Island. After prior discussion about the survey with key persons, the research objectives and questionnaire were explained in the annual meeting of the Board of Directors of the Council for Promotion of “Toki-to-kurasu-satozukuri” (community development living in harmony with Toki), in cooperation with the Sado Municipality Agriculture Policy Division, in February 2020. The board made the resolution to allow the survey and 415 questionnaires were handed to Toki-to-kurasu-satozukuri council members during the annual general meeting. A total of 279 (67%) responses were received by the end of April 2020.

GIAHS-related factors (i.e., farmers’ opinions towards the GIAHS’s effects on youth involvement, the capability to enhance agricultural products, and tourism management) were incorporated in the questionnaire using a three-point ordinal scale (1–strongly yes, 2–not sure, and 3–strongly no). Sociodemographic factors were also gathered via the questionnaire to obtain baseline data for the farmers. Data were analyzed using ordinal logistic regression and a general linear model in SPSS v.27. Tests of parallel lines and model fit were conducted to determine whether statistical assumptions were met. Lastly, qualitative questions were gathered regarding the farmers’ opinions on the impact of the GIAHS on youth involvement, Sado Island branding, and tourism management. The responses given in local Japanese were translated to English by the authors.

3. Results

To understand the current situation of farmer involvement with the GIAHS in Sado Island, their perceived level of involvement was determined using a three-point scale, which revealed that only 43.7% (122 of 279) of the sampled farmers feel that they are involved in the GIAHS, while 56.3% (157 of 279) feel uninvolved or unsure towards the GIAHS (Table 2). Similarly, only 38.7%, 59.1%, and 49.8% of the farmers feel that the GIAHS gives pride and confidence to youths, enhances agricultural products/brand, and promotes tourism, respectively. When viewed at the perspective of their current farming method, which is predominantly special farming (77.3%) (i.e., it complies with GIAHS regulations) and organic farming (10.8%), the farming method and high frequency of farmers who feel unsure or uninvolved towards the GIAHS do not appear to agree with each other.

Table 2.

Frequency distribution table for GIAHS-related and sociodemographic factors among Sado Island farmers.

3.1. Relationship between GIAHS Involvement and Youth Involvement, Tourism, and Branding

To provide an explanation for this observation, various sociodemographic, and GIAHS-related factors relating to Sado Island farmers were used as predictors against their level of perceived involvement towards the GIAHS. The three GIAHS factors evaluated in this study were the common themes of Japanese rural farming, namely: youth involvement, brand promotion, and tourism enhancement [28,29,30]. All three variables were found to be positively related with the GIAHS involvement score, such that farmers who feel that the GIAHS does not promote youth involvement, promote Sado Island brand, and enhance tourism are 17.4%, 38.8%, and 49.4% more likely to feel uninvolved with the GIAHS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship between various GIAHS variables and the farmers’ perceived level of GIAHS involvement using ordinal logistic regression a.

3.2. GIAHS Involvement and Youth Inclusivity

Eight sociodemographic factors were used as predictors of the Sado Island farmers’ perceived level of GIAHS involvement (Table 4). The effects of age, farm/paddy area, yield, climate change effect perception, and farming method were found to have no significant impact on perceived GIAHS involvement. On the other hand, farmers who reported to be participating in exchange programs, either voluntarily or with subsidy, are more likely to feel involved with the GIAHS. In terms of age, 80.3% (224/279) of the sampled Sado Island farmers are 60 years old and above. Of the 15 farmers who are 49 years old or younger, only one third (5/15) reported being involved in the GIAHS. This underrepresentation of youth in GIAHS activities appears to have contributed to the dilution of the effect of age on GIAHS involvement.

Table 4.

Relationship between various sociodemographic variables and the farmers’ perceived level of GIAHS involvement using a general linear model.

3.3. GIAHS Involvement in Tourism and Branding

Sado Island has become known for their Tokimai brand of rice. This integration of the conservation of the local Toki bird population with local farming has contributed to the 0.6% growth rate of tourism in the Niigata prefecture, which amounts to roughly 400,000 guests using local accommodation since the introduction of the program [31]. This also helped to address the problems of livelihood insecurity in the island, as raised by Su and Kawai (2009) [27]. In this study, the effects of farmer expectations on ECA and selling location on perceived GIAHS involvement were also tested. In terms of selling location, farmers who sell directly to consumers were more likely to perceive themselves to be involved with the GIAHS than those who sell at other locations (Table 5).

Table 5.

Relationship between various selling locations and the farmers’ perceived level of GIAHS involvement using a general linear model.

In addition to micro-level predictors, the effect of farmer expectations of ECA on GIAHS involvement was also tested (Table 6). In line with the theme of GIAHSs that relates to ecological conservation, farmers who are participating in the ECA program for carbon sequestration and conservation of biodiversity reasons were more likely to feel involved with the GIAHS, which agrees with previous studies [9,13]. In addition, farmers who are doing ECA to promote the local industry are also more predisposed to feel involved with the GIAHS, which also agrees with other studies, such as in Vafadari (2013), which identifies tourism as a key stimulant of local industry because it opens new jobs and enhances the attraction of rural lifestyles in GIAHS communities [32]. Indeed, the Sado Island tourism webpage features Toki Museum tours, sightseeing, and forest parks [33].

Table 6.

Relationship between farmer expectations of ECA and the farmers’ perceived level of GIAHS involvement using a general linear model.

To determine if the farmers’ global perspective on ECA activities influences their perceived involvement towards the GIAHS, their answer regarding the effect of ECA on climate change was used as predictors for their level of perceived involvement with the GIAHS. Here, farmers who believed that ECA is an adaptation to climate change were twice as likely to feel involved with the GIAHS than those who do not (Table 7). This agrees with the earlier observation on farmer expectations regarding ECA. Testimonials such as that by Respondent 153 reflect this trend from a farmer’s point of view:

Table 7.

Relationship between farmer-perceived effects of ECA on climate change and the farmers’ perceived level of GIAHS involvement using ordinal logistic regression a.

“Produce food that suits climate change. Sell them fresh with safety and good taste. This should be managed through institutional strategy under good leadership. Hotels should use the branded rice produced in Sado.”

4. Discussion

Various studies have emphasized the importance of analyzing farmers’ knowledge and opinions which heavily influence their involvement and productivity in different aspects of agriculture [34,35,36]. In Japan, which is dominated by landscape types that give high value to the linkage of nature, biological diversity, and its surrounding communities, GIAHS sites have been continuously increasing since 2011 [11]. While it is good to see the increase in GIAHS sites in Japan and worldwide, the main caretakers of rural communities—the farmers situated in these sites—should equally be considered. As Rhoades (1984) argues, a full circle should be completed when it comes to the implementation of agricultural technologies and activities, such that farmers are equally involved and a part of the process [36]. Otherwise, the diffusion of technologies would face difficulties and farmers may tend to feel uninvolved, thereby leading to less synchronicity between the agricultural initiative and its target stakeholders.

In this study, the Sado Island’s farmers’ perceived involvement in the GIAHS was explored, and it showed that more than half of the 279 farmers interviewed (56.3%) feel unsure or uninvolved, despite being situated in a decade old GIAHS site. This appears to be contradictory with the primary farming methods being used by the farmers, which focus on ECA and comply with GIAHS regulations. To further understand this disconnect, the study analyzed farmers’ perceived involvement as it related to three common themes of Japanese rural farming, which are: youth involvement, brand promotion, and tourism enhancement. It was found that all three factors are positively related to the farmers’ perceived GIAHS involvement, thereby accentuating their importance when it comes to crafting policies aiming to increase farmer involvement in the GIAHS.

Looking at the age demographics, a huge percentage (80.3%) of farmers are 60 years old and above, which highlights the lack of youth involvement, not only in GIAHS sites, but in various agricultural sectors in Japan. Recent papers, such as that by Reyes et al. (2020), have indeed highlighted the negative effects of farmland abandonment and the underuse of farming resources resulting from Japan’s decreasing and aging rural population [13]. This same sentiment has been observed among the submitted testimonials of the interviewed farmers, such as that by Respondent 269, who stated the following:

“There are many abandoned lands due to lack of successors. Lands are overgrown by various weeds, such as Solidago canadensis var. Scabra, Ambrosia artemisiifolia which flowers yellow during autumn and winter, making it look ugly or not cared for, which is far from the image of GIAHS. First, such land should be managed properly and brought under proper cultivation.”

Sado Island farmers also recognize the alarming issue of farmer shortage in the future because of the increasing trend of youth exodus; hence, they are also voicing their opinions on how to attract people to farm in Sado Island. The narrative of Respondent 131 clearly shows this:

“There will be a shortage of people who will continue farming in the near future. Attract the people who are fed up of city life and loves the countryside to create a natural living environment. People with allergies, retired life, and kids can come to live in Sado. This will create circulatory connectivity in different aspects between Sado and the cities, which will eventually attract the youths to Sado, increase their movements to and fro, making the livelihood more active and connected with the cities as well.”

This highly agrees with the findings of Usman et al. (2021), who highlight the desperate need of rural areas for agricultural workers in connection with Japan’s aging farmers’ population, to mitigate the increase in Japan’s dependency for international food products and high import expenses [37].

Further analyses have shown that farmers’ participation in exchange programs also increases their likelihood to feel involved with the GIAHS. To this end, participation in exchange programs may thus play a key role in not only encouraging the younger generations of farmers, but also enhance the transfer of intangible farming inputs, such as techniques and managerial skills [30]. This view was also shared by Respondent 276, who stated that:

“There is a need to secure people to continue GIAHS. All the GIAHS sites in Japan should come together to promote and enhance it through public relations in universities and colleges and make it part of lectures to get the interest of students who would work on it in the future. First, orient them about GIAHS in general and different GIAHS in Japan, and let them participate in field studies and internships in a GIAHS of their choice for them to interact and learn the local culture, as well as experience the local livelihoods. Afterwards, let them reflect about it and how they can be involved in it in the future to improve.”

This theme was also explored by Yamashita (2021), who focused on how Japanese traditions can be saved by analyzing urban university students’ participation in rural festivals [38]. Interestingly, the case site of the study is also a GIAHS in Japan, particularly the Noto region in the Ishikawa prefecture. The study recommended that better collaborations should be established between urban youths and their participation in rural festivals, which means that more focus should be given in the management of festivals and how outside support can be further increased. These can help alleviate the discontinuation of rural festivals and loss of cultural values. This is also in connection with what Sado Island farmers are voicing out in this study, which is the need to attract youths to Sado Island, thereby implying that they are also aware of the negative consequences if the common trends of youth exodus and rural disinterest will continue.

The narratives of Sado Island farmers and various literature that established the interlinked issues of farmland abandonment, the aging population, youth exodus, and farmer shortages clearly show the need for more policies that would cater to the strengthening of Japan’s agriculture. Based on this paper’s findings, participation in exchange programs may increase the chances of attracting people, especially the youth, to rural areas and help them become more involved in addressing issues in the field of agriculture. With the increase in youth participation, modern solutions can also be applied as rural areas struggle to adapt in the changing world.

With a high growth rate of tourism in the Niigata prefecture, it is not surprising that farmers in this study feel more involved in the GIAHS when they sell directly to consumers. However, looking at the frequency distribution, selling to agricultural cooperatives was the most predominant choice among the farmers (93.5%). This inconsistency was elaborated upon in the testimonials of the farmers, with many entries commenting on the poor uptake of the Tokimai brand across other industries and markets, such as restaurants and supermarkets. This was clearly shown in the response of Respondent 121, who stated that:

“Last year, I participated in the public relations sale of rice in Tokyo station, along with the city officers. Nearly 100% of the passers-by did not know about GIAHS, which is so unfortunate.”

A similar sentiment has been shared by Respondent 141:

“GIAHS alone will not enhance the tourism to brand the hotels, other facilities and services using the branded products of the island.”

Respondent 162 also shared some sentiments on how the GIAHS should complement agriculture:

“It is good to make use of GIAHS for tourism development in the island. However, it is not clear how it helps in enhancing the island’s farming and primary industry. If there is no clear picture/explanation how GIAHS and tourism development can enhance farming, the farmers and youth may not be interested (e.g., How will hotels use rice, vegetables, and fish produced in the island to serve the tourists with a delicious and attractive dish?). It is said that bigger hotels don’t have repeaters (supposedly the food they provide is not delicious) while the homestay pensions serving local food have repeaters. City dwellers visit Sado not only for its nature but also for its food, as well as its hospitable people with warm personalities (heard that the cooks in bigger hotels are dispatched from Kansai (western part of Japan) or foreigners). The concept should be not agriculture for tourism but tourism for developing agriculture.”

These narratives are in line with the point raised by Ohe (2013), who highlights the generation gap between younger and senior generations in recognizing the value of rural tourism, as well as the urban–rural mismatch with regards to rural tourism desires and expectations [29].

This study also found that the Sado Island farmers give high importance to ECA as an adaptation to climate change, thereby highlighting how farmers also prioritize their concern for the environment, in addition to their economic needs. This is also in line with their ECA expectations to promote their local industry, sequestrate carbon, and conserve water quality. Various studies have also shown that farmers’ abilities and individual decisions to adopt environmentally friendly farming methods contribute a lot to mitigating climate change [39,40]. Therefore, maintaining this mindset in farmers is crucial and more studies should be conducted on how to sustain it.

5. Conclusions

Results from the survey in this study have shown a higher incidence of reduced farmer involvement in the GIAHS. While it is one of the direct goals of GIAHS designation to promote awareness and visibility for the farmers working in these sites, results from this study do not support the notion of a direct relationship between farmer visibility and farmer involvement as previously hypothesized. To further understand this observation, the effects of various sociodemographic and GIAHS factors on farmers’ perception towards GIAHS involvement were tested. Negative perceptions of the promotion of youth involvement, Sado Island branding, and tourism management has an enhancing effect on reduced farmer perceptions towards GIAHS involvement. Further evidence presented through the various farmer responses corroborate this observation, prompting an integration of farmer-level input towards the community-level implementation of GIAHSs.

Upon evaluation of the effects of farmer expectations on their perceived GIAHS involvement, it was found that the promotion of local industry has an enhancing effect on farmer involvement. This observation hints at the need for better diffusion of the resulting branding (Tokimai) from the GIAHS initiative to other local industries in Sado Island, as well as the need to target consumers who may not know about Tokimai. Based on farmer responses, there is a need for better uptake of the Tokimai branding across different local industries, such as restaurants, hotels, and supermarkets, for the continuous development of farmer communities and GIAHS sites.

The enhancing effect of carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation towards farmer perceptions on GIAHS involvement was also shown, as expected of an environment-conscious community. This is in alignment with the observation that farmers who feel that ECA is an adaptation to climate change have a higher likelihood of feeling involved with the GIAHS. A study focusing on the effects of various farmer-related factors towards ECA continuation may also provide additional insights on the holistic view of the integration between farmer activities with biodiversity conservation.

While the results of the study cannot be used to fully represent other GIAHS sites in Japan because of the differences in landscape types, locations, and typologies, it can serve well as a reference for local government officials and policymakers on strengthening and developing the GIAHS efforts across Japan, and other countries as well. The study further encourages more research on other GIAHS sites in Japan, with more robust samples and results, which can then contribute to their sustainability. Moreover, studies on GIAHSs around the world with similar characteristics will be needed to enhance the management of GIAHS sites, in connection with the findings of this paper. When magnified on a global scale, the themes explored in this study would lead to a deeper interplay between farmers’ knowledge and perception and GIAHS objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; methodology, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; software, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; validation, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; formal analysis, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; investigation, K.L.M.; resources, K.L.M.; data curation, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; writing—review and editing, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; visualization, K.L.M., C.M.G., and W.F.A.J.; supervision, K.L.M.; project administration, K.L.M.; funding acquisition, K.L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for Promotion of Sciences (JSPS); JP JSBP 120197904. Authors and funding agency have no conflict of interest.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University on 10 July 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study in the annual meeting of the Board of Directors of the Council for Promotion of “Toki-to-kurasu-satozukuri” (community development living in harmony with Toki).

Data Availability Statement

Questionnaire survey data can be available form the first author upon request.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the part of the findings of the joint research project, “Moving Towards Climate Change Resilient Agriculture: Understanding the Factors Influencing Adoption in India and Japan”, Principal Investigator: Keshav Lall Maharjan, funded by Japan Society for Promotion of Sciences (JSPS); JP JSBP 120197904. Authors would like to thank the members of the project, Akinobu Kawai, Professor by special appointment, The Open University of Japan and Akira Nagata, Visiting Research Fellow, United Nations University, Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability, Japan for their valuable inputs in conceptualization of the research project, constructing questionnaire and conducting the survey. The authors are also thankful to, Shinichiro Saito, Chair, Board of Directors, and the members of the “Toki-to-kurasu-satojukuri suishin kyogikai” (Council for Promotion of Community Development Living in Harmony with Toki) and Sado Municipality Agriculture Policy Division for their cooperation in conducting the survey. The authors are grateful to Ruth Joy Sta. Maria for her expertise in the creation of figures for this paper. The earlier version of this paper was presented orally in, International Conference of Agricultural Economists, 17–31 August 2021—online.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- FAO. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems: Combining Agricultural Biodiversity, Resilient Ecosystems, Traditional Farming Practices and Cultural Identity; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Koohafkan, P.; Altieri, M. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems—A Legacy for the Future; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems, Geographical Indications and Slow Food Presidia; Technical Note; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IFAD. Creating Opportunities for Rural Youth; 2019 Rural Development Report; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zulu, L.C.; Djenontin, I.N.S.; Grabowski, P. From diagnosis to action: Understanding youth strengths and hurdles and using decision-making tools to foster youth-inclusive sustainable agriculture intensification. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.F.; Li, X.B. Global understanding of farmland abandonment: A review and prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1123–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwoga, E.T.; Ngulube, P.; Stilwell, C. Managing indigenous knowledge for sustainable agricultural development in developing countries: Knowledge management approaches in the social context. Int. Inf. Libr. Rev. 2010, 42, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Nazroo, J.; Vanhoutte, B. The relationship between rural to urban migration in China and risk of depression in later life: An investigation of life course effects. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiu, E.; Nagata, A.; Takeuchi, K. Comparative study on conservation of agricultural heritage systems in China, Japan and Korea. J. Resour. Ecol. 2016, 7, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS); MAFF: Tokyo, Japan, 2019.

- Nagata, A.; Yiu, E. Ten Years of GIAHS Development in Japan. J. Resour. Ecol. 2021, 12, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraiappah, A.; Nakamura, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Watanabe, M.; Nishi, M. Satoyama–Satoumi Ecosystems and Well-Being: Assessing Trends to Rethink a Sustainable Future (Policy Brief 10-7); UNU-IAS: Yokohama, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, S.R.C.; Miyazaki, A.; Yiu, E.; Saito, O. Enhancing Sustainability in Traditional Agriculture: Indicators for Monitoring the Conservation of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Agnoletti, M. Agricultural Heritage Systems and Landscape Perception among Tourists. The Case of Lamole, Chianti (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A.; Yague, J.L.; de Nicolas, V.L.; Diaz-Puente, J.M. Characterization of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducusin, R.J.C.; Espaldon, M.V.O.; Rebancos, C.M.; De Guzman, L.E.P. Vulnerability assessment of climate change impacts on a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) in the Philippines: The case of Batad Rice Terraces, Banaue, Ifugao, Philippines. Clim. Chang. 2019, 153, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohsaka, R.; Matsuoka, H.; Uchiyama, Y.; Rogel, M. Regional management and biodiversity conservation in GIAHS: Text analysis of municipal strategy and tourism management. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2019, 5, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilina, V.; Grigoriev, A. Information Provision in Environmental Policy Design. J. Environ. Inform. 2020, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C.; Yang, L.; Bai, Y.Y.; Min, Q.W. The impacts of farmers’ livelihood endowments on their participation in eco-compensation policies: Globally important agricultural heritage systems case studies from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajihara, H.; Zhang, S.; You, W.H.; Min, Q.W. Concerns and Opportunities around Cultural Heritage in East Asian Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Timothy, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Min, Q.W.; Su, Y.Y. Reflections on Agricultural Heritage Systems and Tourism in China. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 15, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.; Miniard, P.; Engel, J. Consumer Behavior, 10th ed.; Thomson/South-Western: Mason, Ohio, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dessart, F.J.; Barreiro-Hurle, J.; van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: A policy-oriented review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalvo, C.M.; Tirol, M.S.C.; Moscoso, M.O.; Querijero, N.J.V.B.; Aala, W.F., Jr. Critical factors influencing biotech corn adoption of farmers in the Philippines in relation with the 2015 GMO Supreme Court ban. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalvo, C.M.; Aala, W.J.F.; Maharjan, K.L. Farmer Decision-Making on the Concept of Coexistence: A Comparative Analysis between Organic and Biotech Farmers in the Philippines. Agriculture 2021, 11, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M. Column: Endangered Species in Japan: Ex Situ Conservation Approaches and Reintroduction in the Wild. In Social-Ecological Restoration in Paddy-Dominated Landscapes; Usio, N., Miyashita, T., Iwasa, Y., Eds.; Ecological Research Monographs; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Kawai, A. Comparative Study on the Release Project of Crested Ibis Nipponia Nippon among Japan, China and Korea focusing on Eco-diversity and Agro-environmental Issues. J. Open Univ. Jpn. 2009, 27, 75–91. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ohe, Y. Characteristics and issues of rural tourism in Japan. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 115, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y.; Kurihara, S. Evaluating the complementary relationship between local brand farm products and rural tourism: Evidence from Japan. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, T.; Lobley, M.; Errington, A.; Yanagimura, S. Dimensions of intergenerational farm business transfers in Canada, England, USA, and Japan. Jpn. J. Rural Econ. 2008, 10, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Japan National Tourism Organization. 2019 Accumulated Number of Guests at Accommodations by Prefecture (Niigata Prefecture); Japan National Tourism Organization: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. Available online: https://statistics.jnto.go.jp/en/ (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Vafadari, K. Exploring Tourism Potential of Agricultural Heritage Systems: A Case Study of the Kunisaki Peninsula, Oita Prefecture, Japan. Issues Soc. Sci. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sado Tourism Association. True Sado: Sado Official Tourist Information; Sado Tourism Association: Sado, Japan, 2021; Available online: https://www.visitsado.com/en/ (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Kross, S.M.; Ingram, K.P.; Long, R.F.; Niles, M.T. Farmer Perceptions and Behaviors Related to Wildlife and On-Farm Conservation Actions. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekepu, D.; Tirivanhu, P.; Nampala, P. Assessing farmer involvement in collective action for enhancing the sorghum value chain in Soroti, Uganda. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2017, 45, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rhoades, R. Tecnicista versus campesinista: Praxis and theory of farmer involvement in agricultural research. In Coming Full Circle: Farmers’ Participation in the Development of Technology; Matlon, P., Cantrell, R., King, D., Benoit-Cattin, M., Eds.; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, M.; Sawaya, A.; Igarashi, M.; Gayman, J.J.; Dixit, R. Strained agricultural farming under the stress of youths’ career selection tendencies: A case study from Hokkaido (Japan). Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R. Saving tradition in Japan: A case study of local opinions regarding urban university students’ participation in rural festivals. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2021, 5, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, R.; Dinar, A. Climate Change, Agriculture, and Developing Countries: Does Adaptation Matter? World Bank Res. Obs. 1999, 14, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Agarwal, A.; Gornott, C.; Sachdeva, K.; Joshi, P.K. Farmer typology to understand differentiated climate change adaptation in Himalaya. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).