Abstract

In this paper, the authors present an innovative approach to measuring the resilience of a market system—the Market Systems Resilience Index (MSRI). The MSRI has been developed both to guide development practitioners in the process of conducting resilience assessments and to promote the inclusion of all relevant actors within a market system. A narrative review of the evolution of resilience measurement is presented including identifying the gaps and challenges that remain. Some of these include balancing comparability and contextualization of the questions, understanding how often to perform the survey, and determining how many market actors are needed to properly assess the resilience of the market. This is followed by outlining the development of the MSRI and how it fills some of the existing gaps including the addition of households into the market analysis while creating a set of questions that are consistent while allowing for some optional questions to add nuance. Examples from Nepal and Bangladesh are used to highlight the types of findings that come from using the MSRI. Finally, we describe how these results may be used to inform and guide program management and design of projects.

Keywords:

resilience; measurement; market systems; development; Nepal; Bangladesh; adaptation; management 1. Introduction

The term “resilience” has crossed over from the natural science field into the lexicon of international development [1,2]. Within the development field, there is a constant tension between the short-term gains of project activities, long-term goals, and the sustainability of the impact of development projects once funding has ended. It is also increasingly important to ensure that gains already achieved will not be eroded and that current and future projects are not set up for failure as the enabling and natural environments shift due to climate change. The concept of resilience as defined by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) is the “ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of the hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions” [3] (p. 24). This reflects the overarching consensus found in many disciplines that view resilience as the ability to adapt to, and function during and after times of stress [1]. Resilience provides a framework to explore community, household, and individual needs to cope with changing conditions in complex environments from a holistic perspective; combining analytical lenses from ecology and political economy, it can be applied to different levels and systems [2]. As such, resilience is applicable to the systems and enabling environments in which development practitioners and projects operate. In the development sector, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) applies resilience thinking in its actions towards reducing chronic vulnerability and promoting inclusive growth [4] (p. 6). The concept of resilience helps answer questions such as why one household might be unable to recover from a shock, while their neighbor was able to cope, or how robust a community’s social safety nets may be in the face of increasingly severe natural hazards.

In the face of climatic variability and uncertainty, development practitioners need to better understand what works and what does not; this is also being demanded more by donors [5,6]. To do so requires establishing both quantitative and qualitative measures that contribute to understanding resilience. With a deeper understanding of why one system is resilient while another is not comes the ability to replicate these resilient systems so that all communities can better withstand shocks and stresses associated with climate change. The purpose of this paper is to briefly review the concept of resilience measurement in the literature and practice, and within this context, to introduce the Market Systems Resilience Index (MSRI), a novel tool for measurement and analysis of resilience that specifically includes all relevant actors within a market system.

2. Literature Review

Resilience is not a static trait, but an emergent property that is the product of a complex system; complexity theory posits that the only way to test thresholds in complex systems is by crossing them [7]. Thresholds are critical points at which “the behaviour of some system or the values of some values shift significantly” [4] (p. 12). How architects of resilience measurement tools answer the essential questions of resilience—for whom, to what, through what, and to what end—dictates the composition and applicability of the resilience measurement tool [8].

In this paper, the authors adopt the definition for market system resilience set out by the USAID, which is “the ability of market systems to allocate resources, draw on system-level resources (such as social safety nets, social capital, the financial system, or government assistance), and innovate in order to solve problems in the face of shocks and stresses” [4] (p. 6). This definition nests within the larger discussions and definitions of resilience in regard to human wellbeing and ecological boundaries, while focusing attention on the market system dynamic that interacts with these other two classic spheres of resilience scholarship. Below is a review of some conceptual frameworks and measurement tools related to resilience.

2.1. Review of Existing Tools

There is no systematic agreement on a single definition of resilience; as such, there is no universal agreement on the defining properties or determinants of resilience [1]. The conceptual diversity within the resilience discourse hampers the creation of standardized metrics, as frameworks spawn competing metrics and tools [9]. Below is a sample of competing frameworks.

Bahadur et al. [10] break down resilience into three capacities—adaptive, anticipatory, and absorptive—in their Three As approach for the UK-funded Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters (BRACED) resilience-building program. Bahadur et al. [10] do not include transformative as a capacity, stating that transformation is not a type of capacity, “but rather [it] is an approach to holistically and fundamentally build, reshape and enhance people’s capacity to adapt to, anticipate and absorb shocks and stresses” (p. 12). The authors are in agreement with the view that ‘transformative’ itself is not a capacity of resilience, as transformation would be the result of adaptive, anticipatory, and absorptive capacities as well as other endogenous and exogenous factors culminating in a new state. In describing transformation as an approach, Bahadur et al. [10] note that transformation is generally used to describe deliberate attempts to achieve desired outcomes rather than being a quality or element possessed by actors or systems. This stands in direct contrast to the theoretical framing used by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN), which is predicated upon a division of capacities as adaptive, absorptive, and transformative [6,11,12]. Bahadur et al. [10] use the Three As approach as a conceptual framework for categorizing project impacts on resilience. The strength of the Three As approach is its simplicity; however, how “readily recognizable” these three capacities are as discrete entities is debatable [10] (p. 8). While the Three As is a relatively simple means of categorizing capacities, other frameworks give in-depth outlines and guidance for measuring and understanding resilience at various levels such as household, food systems, and market systems.

Mercy Corps STRESS: Strategic Resilience Assessment is a framework designed to be applicable to many contexts [5]. STRESS provides a workflow process to follow with guiding steps and questions to frame decision making; each assessment is project-specific with predefined ‘development visions’ and specific analyses and outcomes expected to be produced at every step in the process [5]. The ultimate outcome of a STRESS assessment is to revise an existing project theory of change and implement this into adaptive management [5] (p. 8). STRESS includes social, ecological, and economic systems as key elements in understanding the dynamics of resilience [5] (p. 9). Although laudable as a mixed-methods approach, STRESS may not be comparable between projects even if these projects are working in the same focus area—whether geographically or thematically related, because of how highly project-specific the STRESS process is. This decision reflects Mercy Corps’ overarching organizational decision for why a STRESS assessment is being carried out and for what purpose the results will be used, i.e., as an adaptive management process of individual projects [13] (p. 6).

Similar to STRESS, GOAL aims to bring a resilience-informed approach to development and humanitarian interventions [14]. While Mercy Corps’ outward-facing documentation only includes workflow steps, GOAL’s toolkit provides worksheets, specific determinants, and example risk matrices [14]. Predicated on socio-economic systems where households, market systems, and planetary boundaries [15] are included collectively, GOAL’s resilience matrices are generated from the performance of an actor assessment, relationship assessment, system assessment, vulnerability assessment, and stakeholder engagement assessment [14]. While GOAL couches itself as a diagnostic tool, the multiple detailed steps involved make it impractical for many situations, as it is a very time-consuming process. Moreover, because of the commitment of resources involved in executing the toolkit in its entirety, it is unlikely to be repeated; thus providing only a static snapshot and is, therefore, liable to be what d’Errico et al. [16] describe as an “inherently descriptive” exercise (p. 14).

Different from GOAL, which aims to diagnose the resilience of various systems, are measurement tools that have been formulated to a specific system or challenge facing development work. The Food Security Information Network Resilience Measurement Technical Working Group (FSIN) brought together experts in the field of food security to discuss and disseminate guidance on conceptualizing resilience measurement for food systems [16]. This culminated in a causal framework categorized under three components: an ex-ante component, a disturbance component, and an ex post component [16]. The FSIN published seven technical papers out of these collaborations with theoretical guidance for developing resilience measurement tools (https://www.fsinplatform.org/index.php/resilience-measurement) (Accessed on 10 August 2021). The working group proposed five resilience indicator categories based on the literature from ecology [6]: (i) critical outcomes, (ii) disturbance events, (iii) threatening conditions, (iv) disturbance modifiers, and (v) systemic contexts (p. 10) that are measured in respect to their sensitivity to three properties: (i) thresholds and tipping points (threshold property), (ii) rates of change and trajectories (temporal property), (iii) cross-scale dynamics (spatial property) (p. 12). While the reports offer sound theoretical advice, the FSIN recognizes that measuring resilience will have little impact if not directly related to decision making [17]. Therefore, a challenge with the extensive criteria proposed by the FSIN is the feasibility of carrying out such measurements, especially for smaller organizations that are not as well funded as UN agencies or major international non-governmental organizations, and communicating these results in an understandable and timely manner to decision makers.

The Resilience Index Measurement Analysis II (RIMA II) developed by the FAO is a practical analytical tool that builds upon the guidance issued by the FSIN [18] for measuring the resilience of food security [19]. The application of absorptive, adaptive, and transformative capacities faces similar difficulties as the Three As approach for systematically delineating indicators for implementation in resilience measurement [19]. RIMA II is based on household-level data related to six modules: (i) access to basic services, (ii) social safety nets, (iii) food security, (iv) assets, (v) adaptive capacity, and (vi) shocks [19]. Both the FSIN and RIMA II encourage using panel data [19] so that measurements are dynamic, i.e., include time dimensions or changes in the outcome variable(s) of interest [17]. RIMA II includes indirect (inferential) and direct (descriptive) variables but does not include “exogenous variables” such as “environment, socio-political, and institutional aspects” [20] (p. 24). RIMA II is also viewed as having “achievements of resilience” that are observable such as changes in monthly per capita food expenditure and dietary diversity [20]. In its full form, the FAO acknowledges that RIMA II is “time- and resource-consuming, and [is] not always feasible in countries affected by fragility and conflict”; therefore, the FAO developed a short-format questionnaire [19].

Although still focused on food security, the measurement tool utilized by the One Acre Fund for impact analysis frames the essential questions of resilience through the lens of the individual farmer. Therefore, in their framework, “diversity” is crop diversity [21]; however, if one is interested in nutrition and food security, then diversity would more likely relate to diet and food consumption of households rather than crop diversity planted [11].

In contrast to RIMA II and the One Acre Fund, which are primarily concerned with different aspects of food security, the Self-evaluation and Holistic Assessment of climate Resilience of farmers and Pastoralists (SHARP) tool addresses the need to better understand and incorporate the situations, concerns, and interests of farmers and pastoralists relating to climate resilience and agriculture at the household level [22]. The SHARP tool is based on the framework developed by Cabell and Oelofse [22] who compiled 13 behaviour-based indicators of agroecosystem resilience combining ecological and social elements. The SHARP tool has been used by a number of programs over the past eight years, but there has been common feedback that the tool is too onerous and is not easily customizable for project use [23].

Few tools focus chiefly on market systems resilience (MSR), though they do exist [8,24]. One such measurement tool is the Agricultural Cooperative Development International/Volunteers in Overseas Cooperative Assistance (ACDI/VOCA)’s Market Systems Diagnostic tool. This tool has been applied in Honduras to measure the competitiveness, inclusivity, and resilience of the market system at the industry level [24]. The Market Systems Diagnostic tool primarily assesses enterprises across a handful of major industries to gauge the health and resilience of the market system as a whole [24]. This tool does not appear to include households or other smaller market actors, which may be because it was developed with and for high-value industries. It also does not take into account other factors that can influence the resilience of the market system, namely the natural environment.

While there are specialized tools to measure resilience at the household level, which bring well-established theory into practice (STRESS, GOAL, RIMA II), and there are tools being developed to measure resilience at the market systems level (Market Systems Diagnostic), there are no tools in common use which bring together theory-based resilience measurement for households and the market system in a way that is replicable, adaptable, and relatively easy to use by development practitioners. Practicality in time and resource requirements for data collection, and flexibility to quickly capture post-shock and long-term development gains are critical requirements to incorporate into resilience measurement tools in order to provide actionable insights for practitioners [9].

2.2. The Market Systems Resilience Index

The MSRI uses a holistic approach to measuring the resilience of the market at multiple levels and accounts for various exogenous factors (e.g., the ecological environment), in contrast to similar tools available. It was first developed by International Development Enterprises (iDE) in 2018 as part of a market development project in Bangladesh. It has subsequently evolved and has been adapted in part based on the market resilience methods and guidance developed under the Resilience Evaluation Analysis and Learning (REAL) Award in the USAID Center for Resilience [8], and the contributions iDE made to the MSR framework for measurement released by the USAID Bureau of Food Security [4]. iDE’s MSR model brings together core elements of resilience to measure and evaluate the effectiveness of any market system to anticipate, withstand, and adjust to external and internal shocks and stresses.

Guidance issued by the USAID for assessing market system resilience recognizes the positive synergies of enhancing participation between market resilience and market inclusion but delineates the two as separate entities to be measured and worked towards [4]. In contrast, inclusivity is embedded in the MSRI from the standpoint of incorporating social dimensions and vulnerabilities into market resilience measurements. This allows the MSRI to capture human dimensions of resilience along with financial aspects, since markets are socially constructed. Integration and inclusion were chosen, recognizing that systemically excluded groups are integral to long-term resilience-building.

The MSRI explicitly includes households in the market system analysis, recognizing that households are a foundational element of market systems as well as an endpoint of these very same market systems. Without these farming households, the rest of the market would not be able to function. While the SHARP tool measures resilience at the household level, it does not adequately capture systems-level domains of resilience. The MSRI overcomes this by including actors at various levels in the market system in its measurement. By including households and market actors in the market system analysis, the MSRI is able to capture a systems perspective of resilience.

The MSRI built upon the agroecological indicators identified in the SHARP tool to create a more holistic tool that acknowledges and ascribes to the theoretical concept of planetary and social boundaries [23]. This sets the MSRI apart from other market systems tools because it bridges the sectoral divide that often delimits climate and the ecological environment as a separate or imposed policy issue. The MSRI recognizes that households, markets, and the ecological environment are interdependent; by including ecological indicators, the MSRI is able to better gauge the extent and effects of these relationships on the resilience of the market system.

Although the agroecological indicators of the SHARP tool were informative to the development of the MSRI, the developers of the MSRI recognized the operational challenges of existing frameworks and tools, the application of which may be cumbersome and time-consuming. Therefore, the MSRI was developed to be a modular tool that is adaptable to specific contexts without losing comparability. In emphasizing comparability, iDE concluded that it would not take the route of STRESS towards creating new individual measurements for each project.

The current version of the MSRI attempts to build upon the experiences gained from previous resilience measurement tools and frameworks, including earlier piloted versions of the MSRI. It attempts to strike a balance between purely qualitative measurements, thus reducing comparability, and purely quantitative measurements thus losing nuances in responses, by including mandatory quantitative questions along with optional qualitative questions. With the MSRI, iDE also wanted to balance including too many market actors and resilience attributes so as not to become either too onerous or too superficial as this would reduce the quality of results. The range of determinants currently used allows the MSRI to cover a wider array of aspects making it more widely applicable than the previously reviewed frameworks. Coupled with its user-friendliness and flexibility, the MSRI is a tool poised for use with a multitude of projects.

3. Materials and Methods

The initial version of the MSRI was first implemented in the Suchana: Ending the Cycle of Undernutrition in Bangladesh program. Suchana (2015–2022) is a multi-sectoral nutrition program that aims to reduce undernutrition that leads to stunting in children under two years of age in the Sylhet and Moulvibazar districts of Bangladesh. The Suchana monitoring and evaluation team developed and piloted a tool called the Systemic Change Tracker (SCT) to understand the changes within the market system caused by program interventions. This tool was developed in part based on the theoretical framework used by the Donor Committee for Enterprise Development (DCED) standard, and employed by many market systems development programs [25]. Some key attributes include using the results explicitly in adaptive management, ensuring continual reflection and refinement, and looking at system-wide impacts. Leveraging the SCT measurement tool within the Suchana project, the team designed a mechanism to measure system-wide resilience: the MSRI [26]. The initial version of the MSRI tool had three predefined principles and nine determinants in the index to measure the resilience of a market system (Table 1).

Table 1.

Original MSRI composition, determinants, and indicators.

The findings from implementing the MSRI in Suchana were shared at the Resilience Measurement, Evidence, & Learning Conference in New Orleans, United States in 2018, and have also been cited by the USAID in their Market Systems Resilience Measurement guidance [8,26]. The findings from the application of the MSRI in Suchana have been used in the program management to inform further intervention design, project planning and assessment, and to refine the MSRI tool itself.

While the first version of the MSRI was innovative and useful for project management and adaptation, iDE and others working in the MSR space recognized that it lacked a household-level resilience component. With this in mind, and with resources offered through the USAID Implementer-Led Design, Evidence, Analysis and Learning (IDEAL) award, iDE began to explore which household-level resilience measurement tools would be most suitable for integration into the MSRI tool. Households were identified as a key component of market systems that was missing from the earlier version of the MSRI, recognizing that markets cannot function without end buyers/sellers.

3.1. The SHARP Tool: Conceptual Framework

In developing the SHARP tool, the FAO consulted with hundreds of experts and field staff including pilots in Uganda, Senegal, and Mali to develop practical questions that mapped to 13 agroecosystem indicators. Table 2 shows the 13 agroecosystem indicators of resilience; the full list of indicator questions is available from [12].

Table 2.

The 13 agroecosystem indicators of resilience at the household level used in the FAO SHARP tool 1.

The SHARP tool has been used by a number of programs over the past eight years, but there has been common feedback that it is challenging to customize the more than 200 original questions to the context being assessed and that to include the full number of questions is overly onerous for the households interviewed.

Combining MSRI and SHARP Frameworks

The original market-level MSRI tool included three principles and nine determinants of market-system resilience as a proxy for market resilience and was primarily focused on the market system with no explicit household-level resilience measurement included. The SHARP tool is a reliable and replicable tool for measuring household resilience but does not adequately capture systems-level domains of resilience. Table 3 shows how iDE has integrated elements of the SHARP tool into the MSRI, by mapping the 13 agroecosystem indicators of the SHARP tool across the nine original determinants of the MSRI, resulting in the second, (current) version of the MSRI. In this second version of the MSRI, iDE reviewed and updated the determinants of market-system resilience, increasing the emphasis on shocks and stresses and incorporating two additional determinants related to the ecological environment and financial considerations (shaded as grey in Table 3) based on evidence collected during initial piloting in Bangladesh and Mozambique. Overall, we feel that the current 11 determinants and 5 principles more accurately and comprehensively measure the resilience of a market system.

Table 3.

The harmonized MSRI tool including both market-level and household-level assessment of resilience (shading indicates additions from the first version).

3.2. Developing Instruments of the MSRI

Converting the conceptual framework into data collection instruments required iDE to develop scoring rubrics specific to the country context in both Nepal and Bangladesh. This required defining system boundaries, including geographic and market area, and creating survey questions that link all levels, i.e., household, input supplier, retailer, and market-actor levels. These survey questions are mapped to the MSRI indicators, determinants and principles (as well as the 13 agroecosystem indicators) so that the different levels can be analyzed within and between market actors, projects, and countries utilizing the same framework. An example of a household-level scoring rubric is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Example household-level scoring rubric with questions matched to Principle 1. Structure of the market; Determinant 1.1 Redundancy.

3.3. Weighting and Aggregation of Survey Responses and Determinant Scores

The quantitative values for each determinant are calculated following the methods described in [27] and summarized below. The questions and response options are customized for each project context and are tested in the field with a light-touch pilot round to ensure comprehension, survey flow, and that appropriate coded response options are included. The aggregate MSRI scores are calculated based on the customized response options on a scale of 0–100 through a summation of the weighted determinants following formulae.

The resulting MSRI score is a composite index computed as the weighted average of the individual determinants as:

is the weight assigned to each determinant, respectively, in centesimal. is the determinant score from 1 to 5 as per Table 5. This is a continuous measure, so it is possible to have a score of 3.2, for example, allowing for hypothesis testing.

Table 5.

Classification of resilience score contribution assessed at the determinant level.

Each survey response option is weighted based on the contextual factors related to that question. Response options that are theoretically contributing to the relevant determinant are weighted higher than the response options that are related to lower levels of resilience. Survey response weights were collaboratively assigned with in-country project managers, technical specialists and survey-based research experts. Survey question weights are equal across all survey questions within each determinant. For the initial round of MSRI analysis, each of the determinants were weighted equally within each principle. Similarly, each of the principles carries an equal weight for this initial round of MSRI analysis.

Survey response, question, determinant and principle weights were assigned and aggregated using R [28]. Moving forward, we anticipate adjusting survey response, question, determinant, and/or principle weights when we can validate results with overlapping data and after corroborating the results obtained using the MSRI with other market systems level resilience measures.

4. Results

From the beginning of the Suchana program, a market systems resilience assessment was integrated into the project timeline. Key objectives of this assessment were to further adapt the MSRI as a quantitative assessment tool and through its implementation, identify areas for improved project interventions to increase the resilience of the households and markets within the project areas.

In late 2020, a total of 322 households, 68 market actors, and 29 other actors were interviewed for the resilience assessment accompanying the Suchana project. Because of the timing of these interviews, iDE was particularly interested to understand the impact of COVID-19 on MSR along with regular climatic disasters impacting the community.

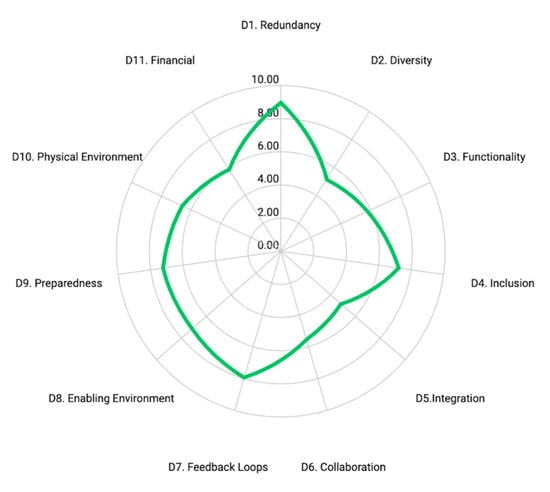

System boundaries were defined geographically by land use density (urban, rural, remote) and land type (haor, hilly, flood-prone, plain), as well as by market actor (local business actors, sales agent, seed retailer, paravet, vaccinator, output buyer) and income-generating activity (aquaculture, poultry, livestock, horticulture, bamboo craft, tailoring). Overall, households showed the highest levels of resilience in Redundancy and Feedback Loops, while Integration, Diversity, and Collaboration all had low levels of resilience, shown in Figure 1. However, the aggregation of all households belies differences which become apparent when one breaks down the scores further. Among the different land types, for example, Haor and Plain land types had the lowest resilience levels, while Floodplain and Hillot land types had the highest resilience levels. Yet, there were no significant differences between households with different income-generating activities.

Figure 1.

Household resilience levels in Bangladesh.

Market actors had high levels of resilience in Redundancy, Diversity, and Integration, and low levels of resilience in Preparedness, Collaboration, and Inclusion across the board. iDE found consistently low scores among vaccinators and sales agents, relative to other market actor types, for almost all of the determinants. These results enabled the Suchana project team to focus project interventions on these areas and actors with low resilience to better utilize time and resources. As the project continues, and further MSRI assessments are conducted, additional in-depth insights will be possible that will help to inform future interventions.

Following deployment in Bangladesh, iDE revisited former project sites in Nepal to gain an ex post resilience baseline and track changes moving forward to assess the lasting impacts of the projects. iDE also hoped to map areas with a potential need for future interventions. Four projects were conducted over different time ranges between 2003 and 2018 in districts across Nepal, working to strengthen the agricultural value chains and climate change adaptation capacities of farmers. In early 2021, the MSRI was deployed to assess elements of resilience in the market system of two value chains: vegetables in the municipalities of Virkot, Waling and Galyang, and essential oils in the municipality of Chapakot, in Syangja District, Nepal. The system boundaries were geographically delineated by the municipality borders and further bounded by market actors (focal person, traders, agro-vets, nursery grower, and community business facilitator), income-generating activities (vegetable and essential oils), and by gender of the household head. Incorporating lessons learned from the contextualization of the MSRI tool in other contexts (like Suchana) decreased the time and resources required to adapt the tool to the new context. Because the basic structure of mandatory questions and mapping the relationship of questions to the determinants had already been developed, the minimal adaptations required were mainly translation and the identification of key actors within the market. The scale of the Nepal analysis was limited due to COVID-19 restrictions, and therefore only 40 households and 17 market actors were interviewed using digital data collection tools. From the analysis that was conducted, COVID-19 was not found to have a major impact on farmers relative to other shocks and stresses; however, this may be due to the timing of the survey, as unfortunately, the burden and economic restrictions of COVID-19 increased substantially in subsequent weeks.

As in Bangladesh, Feedback Loops were found to have the highest resilience at the household level, while Preparedness had the lowest scores across all household subgroups. There were also disparities in resilience between the municipalities with Vikrot having the highest and Chapakot scoring the lowest overall scores. Additional differences were noted between male- and female-headed households. Male-headed households scored higher in six out of 11 determinants (Redundancy, Integration, Feedback Loops, Environment, Preparedness, and Physical Environment), while female-headed households scored higher in the remaining five (Diversity, Functionality, Inclusion, Collaboration, and Financial). When looking at the aggregate index score, there was no significant difference in resilience between male- and female-headed households, although there were differences across the individual determinants.

A notable finding is that when comparing the vegetable and essential oil subsectors, the vegetable subsector shows stronger resilience across ten out of the 11 determinants, with the exception of Inclusion. This could be attributable to the smaller sample size for the essential oils sub-sector analysis, relative to vegetables; however, it could also be due to the longer time that iDE has spent supporting and strengthening the vegetable sub-sector relative to essential oils in this area. As iDE continues to support the essential oil subsectors, future MSRI analyses might capture the effects of successful intervention through increased scores.

Understanding shocks and stresses experienced by households in Nepal, Bangladesh, as well as the different resilience between levels will allow users to probe the market system further in future assessments, using qualitative questions to supplement the quantitative index questions. The results did not strongly indicate the root causes of market weakness, which may be a result of the small sample size (specifically in Nepal); additionally, both the Suchana and Nepal studies are baseline assessments. Future MSRI assessments will help to indicate, for example, the impact of COVID-19 on the market system and household resilience and will allow a deeper understanding of resilience as a dynamic attribute through time. Following these initial applications, the MSRI has recently been adapted to Ghana, Ethiopia, and Zambia.

5. Discussion

The MSRI is being used as a traditional monitoring and evaluation tool, with baselines and endlines to measure the impacts of projects, as well as for more active and ongoing monitoring, evaluation, and adaptive management. iDE is in the process of developing specific activities to efficiently and effectively address low-scoring determinants. This will tie the MSRI directly to project outcomes and give users of the tool a way of both tackling areas of low resilience and measuring whether interventions are having the desired impact. Through results generated from the MSRI, users will be able to refine and develop new interventions over time and better understand the interplay between different interventions and the 11 MSR determinants.

As measurement tools continue to be developed and implemented we will be able to compare not only the MSRI across contexts, but also different resilience measurement tools. The only tool reviewed that explicitly focuses on market systems, ACDI/VOCA, to date has only been applied in Honduras and specifically focused on the tourism sector. Of the remaining tools, only the Mercy Corps STRESS tool was used in Bangladesh [27] and Nepal [13]; however, in both cases they were significantly different from the MSRI. The STRESS assessments were neither within the same geographic region within the countries, during the same seasons (e.g., winter/summer or harvest/planting), nor focusing on market systems explicitly. The underlying purpose of undertaking the STRESS assessments, i.e., mainstreaming resilience and risk reduction in an ongoing humanitarian intervention in the case of Bangladesh and analyzing food security in Nepal, are substantially different from the MSRI, but revealed some interesting findings related to market systems.

In Bangladesh, factors of market systems resilience manifested in the STRESS report in the discussion of economic security and access, inclusion, and ecological fragility [27] (p. 13, 23), low economic access and inclusion found in the STRESS assessment may be expressions of the low resilience scores the MSRI found in integration, diversity and collaboration. However, characteristics of the market system were ancillary to other considerations within the assessment. Resilience assessments would benefit from using the MSRI to analyze where the weaknesses in the market system are. For example, is lack of access because of poor connectivity alone, or are there other challenges related to the market structure such as poor functionality or low redundancy that is hampering access? Observations from the Nepal STRESS assessment regarding the impact of land access (both acreage and type of terrain) [13] (p. 17) bear out the need to include both the physical and enabling environments in resilience assessments. Moreover, caste [13] (p.18) and gender [13] (p.19) came up repeatedly as strongly influencing food security, a finding that is reinforced by the low Inclusion scores found in the MSRI. These overlaps show that some components of resilience transcend and operate at multiple levels thus corroborating the importance of these factors, but as the STRESS assessments were not directly applied to a market system they neither confirm nor challenge the composition of the MSRI. Once more overlaps do occur the insights into the effectiveness, comprehensiveness, and opportunities for improvement will become more apparent.

The MSRI provides a standardized assessment that strives to not be overly project-specific and only requires minimal customization to the context in which it is being deployed. This will allow evaluators to compare results across geographies and find insights from much larger datasets. Since the MSRI will be deployed multiple times in the life cycle of projects with a core set of mandatory questions, it will allow for comparisons over time rather than static snapshots. Although these mandatory questions are universal, the qualitative questions of the MSRI give evaluators flexibility to gather additional data points thus capturing new insights or possible trends. As further MSRI assessments are conducted, more in-depth analyses will be possible, allowing future projects to be more effective in accomplishing project goals. Over time this will give its users insight into the sustainability of past projects and lead to additional evidence for best practices moving forward. iDE is planning to continue rolling out the MSRI in new country contexts, with the goal to establish the MSRI as a benchmark tool for country offices and other development funders, agencies, and organizations to draw upon to assess and compare market systems resilience in different environments.

6. Conclusions

This paper has introduced a novel tool for measurement and analysis of market system resilience that specifically includes all relevant actors as well as social and ecological synergies that contribute to market systems’ resilience. The primary objective of the MSRI is to examine how robust market systems can affect resilience at both the systems and household levels and to provide more detailed information regarding future program scale-up and expansion. The concept of the MSR is a relatively new one; however, its effective assessment using a tool such as the MSRI can provide comprehensive evidence to project managers to inform future decisions related to project implementation, while also providing the project team and donors with evidence related to the impacts the project has on resilience. Given the recent publication of the USAID’s Market Systems Resilience Measurement toolkit [4] and the Market Systems Resilience Guidance that highlights the MSRI [8], this is a critical time to continue improving the MSRI by streamlining the data collection processes and by linking the MSRI to household-level resilience, as both of these have been identified as key areas for MSR improvement [8]. Furthermore, this provides the entire development sector with an opportunity to learn from an additional application of an innovative measurement tool to improve adaptive management and measure systems change. By using the MSRI to measure the resilience of the market system at two or more points in time, projects can identify needed adjustments after the first round of measurement and test whether the adjusted activities led to changes in the market system. The tool bridges a specific gap in the literature and practice, and in so doing may ease some of the tension in the development field between balancing short-term gains of project activities, long-term development goals, and the sustainability of projects in the age of anthropogenic climate change. In doing so, the MSRI may aid in the development field’s ultimate goal of reducing chronic vulnerability and promoting inclusive growth within the bounds of socio-ecological systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.H.C. and C.K.N.; methodology, J.M.H.C., C.K.N., L.H. and N.B.; validation, C.K.N., L.H., N.B., T.P., R.K. and M.H.U.; formal analysis, C.K.N., M.H.U. and R.K.; data curation, T.P., R.K. and M.H.U.; writing—original draft preparation, L.V.B., V.S. and T.P.; writing—review and editing, L.V.B., V.S., J.M.H.C., C.O., C.K.N., M.H.U. and R.K.; funding acquisition, supervision and project administration, J.M.H.C. and C.K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was made possible by a grant from The Implementer-Led Design, Evidence, Analysis and Learning (IDEAL) Activity. The IDEAL Small Grants Program is made possible by the generous support and contribution of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of the materials produced through the IDEAL Small Grants Program do not necessarily reflect the views of IDEAL, the USAID, or the United States Government, United States Agency for International Development: SC-IDEAL-MG-RFA-2019-01; Department for International Development: 204131 grant number 999003063. The Bangladesh portion of the fieldwork was partially funded by the Suchana project, which is in turn funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) of the UK Government (and the European Union (EU).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the National IRB considering research that is not specifically related to human health to be exempt. The research followed the principles set forth in the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

To avoid sharing personal information we have chosen to not make the data available.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the foundational work done by Chiara Ambrosino, Jess MacArthur Wellstein, Bablu Kumer Barua, and Md. Hedyiet Ullah developing the first version of the MSRI. We also acknowledge the support provided by F, Conor Riggs, Deepak Dhoj Khadka, and Stefano Gasparini.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bahadur, A.V.; Ibrahim, M.; Tanner, T. Characterising resilience: Unpacking the concept for tackling climate change and development. Clim. Dev. 2013, 5, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Constas, M.A. Toward a theory of resilience for international development applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14625–14630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- UNISDR. 2009 UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/2009-unisdr-terminology-disaster-risk-reduction (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Downing, J.; Field, M.; Ripley, M.; Sebstad, J. Market. Systems Resilience: A Framework for Measurement; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/Market-Systems-Resilience-Measurement-Framework-Report-Final_public-August-2019.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Levine, E.; Vaughan, E.; Nicholson, D. Strategic Resilience Assessment Guidelines; Mercy Corps: Portland, OR, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/STRESS-Guidelines-Resilience-Mercy-Corps-2017.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- FAO. Core Indicators for Resilience Analysis: Toward an Integrated Framework to Support Harmonized Metrics; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/paragr.raphs/documents/Core_Indicators_Resilience_Analysis_Publication.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Carpenter, S.; Westley, F.; Turner, M.G. Surrogates for Resilience of Social-Ecological. Systems. Ecosystems 2005, 8, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroegindewey, R.; O’Planick, K.; Pulido, T.; Cissé, J.; Van Der Merwe, R.; Meissner, L.; Lamm; Griffin, T. Guidance for Assessing Resilience in Market. Systems; USAID Bureau for Food Security: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.marketlinks.org/resources/resource-guidance-assessing-resilience-market-systems (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Jones, L.; Constas, M.A.; Matthews, N.; Verkaart, S. Advancing resilience measurement. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A.; Peters, K.; Wilkinson, E.; Pichon, F.; Gray, K.; Tanner, T. The 3As: Tracking Resilience across BRACED; ODI: London, UK, 2015; Available online: www.odi.org/publications/9840-3as-tracking-resilience-across-braced (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- FAO. Comparison of FAO and TANGO Measures of Household Resilience and Resilience Capacity; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/paragraphs/documents/FAO_TANGO_Resilience_Measurement_Comparison_Paper.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Choptiany, J.; Graub, B.; Phillips, S.; Colozza, D.; Dixon, J. Self-Evaluation and Holistic Assessment of Climate Resilience of Farmers and Pastoralists; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i4495e/i4495e.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Mercy Corps, Pahal Program–Strategic Resilience Assessment (STRESS) Report. Mercy Corps and USAID. 2019. Available online: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/MC_Nepal_PAHAL_Program_STRESS_Report.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- GOAL. Resilience for Social Systems: R4S Toolkit, User Guidance Manual. 2019. Available online: http://resiliencenexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019-R4S-ToolkitD01-1.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Raworth, K. A Safe and just Space for Humanity: Can We Live within the Doughnut? Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2012. Available online: https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/safe-and-just-space-humanity (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Constas, M.; Frankenberger, T.; Hoddinott, J. Resilience Measurement Principles: Toward an Agenda for Measurement Design; Technical Series No. 1; Resilience Measurement Technical Working Group FSIN: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/paragraphs/documents/FSIN_TechnicalSeries_1.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- d’Errico, M.; Garbero, A.; Constas, M. Quantitative Analyses for Resilience Measurement. Guidance for Constructing Variables and Exploring Relationships among Variables; Technical Series No. 7; Resilience Measurement Technical Working Group FSIN: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: http://www.fsincop.net/fileadmin/user_upload/fsin/docs/resources/FSIN_TechnicalSeries_7.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Resilience Measurement. FSIN. Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/index.php/resilience-measurement (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- FAO. Resilience Index Measurement and Analysis: Short Questionnaire; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/cb2348en/CB2348EN.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- FAO. RIMA-II: Resilience Index Measurement and Analysis—II; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: www.fao.org/resilience/resources/resources-detail/en/c/416587/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Impact in Detail. One Acre Fund. Available online: https://oneacrefund.org/impact/impact-in-detail/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Cabell, J.F.; Oelofse, M. An indicator framework for assessing agroecosystem resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choptiany, J.M.H.; International Development Enterprises (iDE). Personal Communication, 2018.

- Market Systems Diagnostic: Understanding System Health. ACDI/VOCA. Available online: https://www.acdivoca.org/what-we-do/tools/market-systems-diagnostic/ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Kessler, A. Assessing Systemic Change. DCED. 2021. Available online: https://www.enterprise-development.org/wp-content/uploads/4_Implementation_Guidelines_Systemic_Change.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Ambrosino, C.; Wellstein, J.M.; Barua, B.K.; Ullah, M.H. Introducing and Operationalizing the Market System Resilience Index. In Proceedings of the Resilience Measurement, Evidence, and Learning Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 12–15 November 2018; Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/www.ideglobal.org/files/public/RMEL_Conference-R_MSRI_FINAL.pdf?mtime=20190610215110 (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Henly-Shepard, S. Planting Seeds of Resilience in Humanitarian Settings: Rapid Strategic Resilience Assessment Report for the Rohingya Crisis, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. MercyCorps and IOM. 2018. Available online: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Mercy_Corps-IOM_Rapid_Strategic_Resilience_Assessment_Report.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 22 September 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).