Abstract

In a globalized scenario characterized by cogent challenges, sustainable development represents a fundamental objective, according to the agenda of policymakers. This is particularly true with regard to farming, and those agricultural systems that are fully consistent with sustainability in society (health, employment), environment (methane emission, water resource and so on), and economy (source of wealth). Tunisia is one of the world’s top olive oil-producing countries. It is also the country with the largest certified organic olive-producing areas in the world. Moreover, a larger volume of Tunisian olive oil is produced using nearly organic practices, without actually being certified. Given the growing demand for certified products, Tunisia should strengthen its market position by building on its reputation for sustainable farming, through the promotion and the creation of new geographic indications for EVOO. The objective of this paper is to evaluate the impact of GIs and how such kinds of labeling can be more effective, operational, and sustainable, to support the country’s development strategy in this sector. Through an ad hoc quanti-qualitative analysis of Tunisian olive oil value chain, representative of the natural resources, the deep understanding of cultures and traditions of the country, a comprehensive and precise SWOT analysis carried out on the Tunisian olive sector has been performed. This study bears significance as it depicts a specific roadmap that should allow a better application and extension of GI’s initiatives referring to the three pillars of Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations, and by building on the position of Tunisia as an organic origin focusing on five strategic lines: organizational and institutional framework; capacity building improvement; communication and networking roles; the role of TIC and the emergence of new opportunities; financial and support products availability. The final outcome should also aim to shorten the distances between all stakeholders to achieve the goals of the 2030 Agenda in the Mediterranean basin, by removing behavioral and institutional barriers that inhibit the transformations needed to achieve more sustainable economies and societies, by means of a cross-disciplinary dialogue around olive oil chain sustainability and narrowing the gap between research and policymakers.

1. Introduction

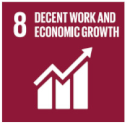

The world olive-growing area is around 11.6 million hectares corresponding to nearly 1.5 billion trees, of which 86.5% is used for olive oil production. The majority of olive-growing areas in the world (71%) are still cultivated using nearly traditional production methods. However, new plantations are substantially increasing by around 162 thousand hectares per year, the majority of which is conducted using an intensive production system [1]. This will not only have an impact on the volume of olive oil production and international prices, but also will increasingly threaten the traditional small scale production model, which has been, for a long time, the dominant typology of this sector. The Mediterranean basin is still the geographical area where almost 98% of the olive oil production is concentrated. In the last decade (2010/2011 to 2020/2021), European countries have cumulated 68% of the world production, including Spain and Italy, with 44 and 11% of the global olive oil volume, respectively. Tunisia, with 6% of the global production, is the second world producer after the EU, with an average production of 192 thousand metric tons across the last decade [2,3]. Figure 1 shows the annual production of Tunisia, which is highly dependent on climatic conditions, fluctuating between 70 and 350 thousand metric tons in 2013/2014 and 2019/2020 respectively, compared to the other traditional producing countries. Actually, olive-producing areas in Tunisia are composed by more than 94% of rain-fed olive groves conducted, whether using conventional or organic traditional producing methods [4], which explains, in large part, the annual fluctuation of the production, along with the natural alternate bearing characterizing the species itself.

Figure 1.

Olive oil annual production of the main world producing countries (2010/2011 to 2020/2021) [2,3].

In the last decade, Tunisia exported an average volume of 157 thousand metric tons of olive oil, which represents 18% of the global exportations and 52% of the non-European exported olive oil in the world (Figure 2). More than 90% of Tunisia’s exports are traded in bulk, while bottled exports are increasing in an uneven way according to the international annual supply and demand.

Figure 2.

Ten years average global exportations of olive oil (2010/2011–2020/2021) [2,3].

Bulk exportations are mainly driven by the demand of the EU countries, which absorbed an average of 66% of the Tunisian olive oil exportations [5]. These are highly dependent on the contingent agreement under the zero duty quota allocated to Tunisia [6]. Italy and Spain have traditionally been the most frequent importers of olive oil from Tunisia to the EU.

As for EVOO prices, Bari (Italy), Chania (Greece) and Jaén (Spain) are the most representative olive oil markets of the European Union. They cover more than 60% of global olive oil production. Prices in these three countries, particularly in Spain, have an impact on other producing countries, and mainly on the oils that they intend to export.

In this competitive environment, characterized by declining agricultural commodity prices in general, and particularly for olive oil, part of the market trend towards traditional and/or quality products with a strong cultural link provides producers with a value-added reward as a result of the existent link to a particular geographical origin, with the opportunity to move away from commodity markets into more lucrative niche markets through differentiation. As such, territorial origin becomes a strategic tool for differentiation in agri-food markets [7].

In the context of geographical indications (GIs), those peculiarities that prove to be appealing to consumers are connected to the unique set of characteristics of specific geographic origin of each good and/or particular production methods used in each site/production area (the notion of “terroir”) [8]. The term “terroir”, as argued by Bowen and Mutersbaugh [9], reflects the connection between origin and quality, by stating that quality itself stems from the selection of specific varieties in each terroir; this is true not only for the viticultural sector, where the term “terroir” originated, but also with regard to the entire agri-food sector, by virtue of the extension of the protection granted to grape varieties to the mentioned whole sector (Loi n° 90–558 du 2 juillet 1990 relative aux appellations d’origine contrôlées des produits agricoles ou alimentaires, bruts ou transformés - Légifrance). In sociological terms, this concept evokes relationships of solidarity, which are developed around destinies, identity, competences, and around the elaboration of shared collective rules [8].

The fundamental role of GIs in this scenario, therefore, is that of providing a credible certification mechanism capable of overcoming the impasse of asymmetric information [10]. In line with the goals of EU quality policy, the peculiarities of those products that embeds unique characteristics resulting from the originating site deserve a strong attention and a specific protection; the objective is, at an initial level of analysis that will be carried on in the present contribution, safeguarding socio-cultural features of the same sites and traditional know-how. Through assigning “Geographical Indication” (GI) to product names, it is possible to trigger a virtuous mechanism capable of fostering consumers’ trust and distinguish quality products, while also helping producers to conquer niche market efficiently. Those products that are under consideration or have been assigned a GI recognition are listed in special registers, together with all relevant information to identify the geographical and production specifications for each product.

As enforced by EU regulations, the GI protection system protects the names of a series of products, by certifying the presence of peculiar qualities, thus fostering their reputation linked to the production territory. GIs comprise PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication). The differences between PDO and PGI are mainly connected to the extent to which each product’s raw materials must come from a certain area or how much of the production process must necessarily take place within the specific same area. As to the cited legal framework, it is vital to refer to “Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs on the protection of Geographical Indications and Designations of Origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs” [11], replacing the Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006, which allowed producers from third countries to finalize trade agreements with the European Union by registering their products (implementing regulation: Commission Regulation (EC) No 1898/2006 of 14 December 2006) [11]. Non-European product names are also allowed to register as GIs, provided that their country of origin has a bilateral or regional agreement with the EU, that foresees the mutual protection of the same product names. On eAmbrosia (the official database of EU GI registers), it is possible to consult GIs applied for, and officially included in, the EU registers, while both EU and non-EU GIs protected under agreements can be checked on the GIview portal. At the time of the present report, these databases do not yet include Tunisian products. However, 9 GIs from Tunisia were included in the database of the World Intellectual Property Organization, according to the Geneva act of the Lisbon agreement on appellations of origin and geographical indications, including one olive oil [12].

It is worth noting that Tunisia, being one of the historical partners of the EU, given the geographical, cultural and trade links accumulated throughout the common history of the Mediterranean basin, has always been a privileged country in the EU development regional policies. The olive oil sector is one of the most prominent examples of a South-North trading for the commodities market. Moreover, a ‘Privileged Partnership’ was established in 2012 between EU and Tunisia, with an ambitious action plan for its implementation. The EU strives to ensure that its sectoral policies identify every possible opportunity for supporting the country’s transition and strengthening ties between Tunisians and Europeans. The support of the initiatives that would develop a new form of economic activities from EVOO GIs and around them, as well as the registration of Tunisian GIs to be protected under agreements, could be very significant in the Tunisian context, opening new horizons, especially in the rural, disadvantaged areas.

The implementation of Geographical Indications in Tunisia is regulated by the Law No. 99–57 of June 28th [13], 1999, aiming to protect and improve the specificity of agricultural and agri-food products. There are two kinds of GIs labels in Tunisia, as defined by article 2 of the aforementioned law. The denomination system is mostly equivalent to the European description. According to the Tunisian Ministry of Agriculture Water Resources and Fisheries, there are 14 registered GIs across the country, including 9 AOCs (equivalent to PDOs); 7 wines, 1 fig and 1 olive oil, as well as 5 IP (equivalent to PGIs); 1 apple, 1 pomegranate, 1 olive oil, 1 date and 1 mint. The labelled products are economically valorized in an uneven way according to the market demand. The first Tunisian GI in olive oil was implemented in 2010 in the region of Monastir—Eastern cost, which obtained the label of “IP” Indication of Origin and was published in the Official Journal of the State in 2010 [14]. Later on, in 2018, another GI label was assigned to the area of Teboursouk—North-west Tunisia, corresponding to a controlled designation of origin “AOC” [15]. Other attempts are being carried out to implement new GIs for olive oil and, to our best knowledge, not particularly for organic olive oil. The already registered GIs are increasingly gaining interest, especially with the orientation of the international market toward more quality, more authenticity, and more traceability [16,17]. However, the actual potential of the existent denominations and the creation of new GIs are still largely under-exploited. Several projects’ initiatives have been carried out to perform inventory lists of potential GIs products not yet registered in Tunisia, including olive oils, and further evaluations have been performed to select the most appropriate locations that better fits the implementation of this model. However, there is still a gap of scientific literature in this regard in the local context. Some authors have studied the potential of particular localities, evaluating their suitability to produce distinctive olive oil, focusing only on the intrinsic quality descriptors of the product. Fares et al. (2016) [18], for example, demonstrated that “AlAlaa” province characterized by ‘Oueslati’ cultivars provides more interesting, balanced and specific physicochemical and sensory profiles that may encouraging the installation of a GI. However, the characterization of each territorial specific circumstances is a fundamental step to ensure an effective implementation of GIs, taking into account the biological and cultural diversity, as well as legal and economic considerations [19,20]. Moreover, it is worth highlighting that the adaptation of the primary transformation sector as well as bottling and marketing operators to the concept of GIs in olive oils is still to be evaluated in depth. Fendri et al. (2020) [21] studied the olive mill’s typology in five potential locations in Northern Tunisia to be able to adopt such a GI approach and reported the high heterogeneity between geographical areas, in terms of equipment, size of the olive mills and qualifications. So far, all the studies published in relation with GIs in Tunisia were focused on the product specification without paying attention to the overall socioeconomic and territorial context. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first report that tackles, in a comprehensive way, the Tunisian experience in implementing GIs as a multi-dimensional instrument for rural and territorial development that deals with the actual barriers at the institutional, operational and behavioral levels. Moreover, there is no literature that evaluates the most appropriate approach to be followed in order to stimulate the creation, the adoption and the economic valorization of GIs for Tunisian EVOO, including the determination of the kind of GI that better fit to local context. This is not the case for organic certification that was studied using a multidimensional perspective [4,22]. Actually, organic, which is one of the four official labels available for agricultural products in Tunisia, has had a substantial improvement in its implementation and economical valorization since the organization of its legal framework between 2005 and 2009. Then, after a substantial increase of certified organic areas up to 255,000 hectares converting Tunisia to the world leader [23], the national strategy 2016–2020, aimed at increasing exports and facilitating access to new markets. The use of GIs as a second lever of the Tunisian olive oil sector, also in combination with organic, is still to be promoted. The role that GIs could play in local development has been discussed in other countries [24,25,26,27], opening new horizons to the local population toward more lucrative markets [8,9,27]. This is particularly interesting for small scale models, such as those that are dominant in the Tunisian olive oil sector. Indeed, 70% of Tunisian farmers produce less than 10 hectares [28], and around 94% of olive mills process less than 100 metric tons of olives per day [5]. It means that the stakeholders are mainly identified as small-scale producers, which is in contrast with the vocation of Tunisia as an origin of bulk exportations. Other countries have successfully extended their GIs in an efficient way, such as Italy [24], Spain [29], and France [30], etc. Similar GI experiences have been shown to be effective in a more challenging socioeconomic context, such as in India [31].

It is vital to consider that consumers are typically willing to pay more for GI products, but the size of the premium may demonstrate differences. Actually, GIs can be seen as the basis for a successful differentiation strategy. According to Porter (1985) [32], differentiation is one possible strategy to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. In a differentiation strategy, firms seek to be unique in their market along some dimensions that are valued by customers, because of their superiority in this respect, and they are rewarded with a premium price. The economic rationale of geographical indications includes the following aspects:

- Consumers may suffer from quality uncertainty and asymmetric information.

- High and low qualities may be sold at the same price.

- High qualities may be crowded out by low qualities (“lemon” problem) [7].

- Quality is due to regional origin.

- Protection of geographical origin may avoid market failure

- Legal protection and associated label: geographical origin turns from a credence to a search characteristic.

- Protection of regional-origin label reduces search costs and, thus, raises consumer welfare.

- Intellectual property right: high-quality producers get a reputation premium and a higher income.

- Imitators and non-original producers are kept away from the market.

- Beneficial for remote regions, rural development, and economic cohesion.

In the context of the present contribution, it is worth citing the important role of GIs for safeguarding biodiversity, local varieties, and seeds, as well as the strong sustainable development approach [33], fully in line with the European Farm to Fork Strategy [34]. Furthermore, the promotion of GI initiatives in Tunisia could better address the issue of knowledge collectivity and identity, by creating a unique interaction through different generations and effective tools, to challenge the dominant industrialization of the global food system [9]. It is, therefore, important to consider alternative distribution schemes (zero km, farmers’ markets, and so on), whose aim is to create a virtuous relationship between producers and consumers, thus enhancing trust and mutual cooperation at territorial level. Furthermore, the peculiarities of GIs products hold a strong potential to foster the multi-functionality of farms [35] and sustainable development; as a matter of fact, the biological properties and the socio-cultural diversity embedded in these products can contribute to safeguarding biodiversity at different levels. As a consequence, coming back to localized productions, it is vital to consider both the strong relationship with their physical environment (agro-terroir), and their being increasingly the result of complex interactions among a set of natural and human factors (socio-terroir) [36,37].

Starting from the aforementioned perspectives, this paper aims at providing a comprehensive quanti-qualitative approach supported by a precise SWOT analysis on the Tunisian olive oil sector, in order to evaluate how can GIs play a role in an effective, operational and sustainable ways to support the country’s development strategy of the olive oil sector being in line with the three pillars of Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. A specific roadmap is designed to make the application and extension of GI’s initiatives more practicable, starting from five strategic lines: organizational and institutional framework; capacity building improvement; communication and networking roles; the role of TIC and the emergence of new opportunities; as well as financial and support products availability.

2. Materials and Methods

Undertaking a process of recognition of a designation of origin for Tunisia’s extra virgin olive oil according to European regulations is a long, complex process that requires the coordinated intervention of different actors, and for which it is appropriate to carefully evaluate the pros and cons of the initiative [12,13,15]. SWOT analysis, also known as the Tows Matrix, is an adequate strategic planning tool to evaluate the internal strengths and weaknesses of a project, a company, a system, an approach and the opportunities and the probable threats stemming from external factors, in any situation in which an organization or a person has to make a decision to achieve a given goal [38]. SWOT analysis allows you to observe "the object" to be analyzed from four different and contrasting points of view. It is, in fact, an effective method of identifying the strengths and weaknesses of a given problem and examining the opportunities and threats to be addressed. It helps to focus the activities in the areas where each producer is most competitive, and those where there are more opportunities.

This methodology, therefore, allows one to represent, in a rational and orderly way, the influence exerted by different agents of the environmental context on the implementation of projects belonging to any system. In relation to this, it is important to differentiate the elements of influence into factors of an exogenous nature and factors of an endogenous nature. Among the endogenous factors, all those variables that are part of the system, and on which, as a rule, it is possible to intervene are considered. On the exogenous factors, on the other hand, it is not possible to intervene directly, but it is advisable to prepare control tools that analyze their evolution, in order to prevent negative events and exploit positive ones.

The use of a SWOT analysis is particularly relevant in local development policies, as a support to the diagnosis of existing problems, and as a search for adequate solutions [38,39]. Therefore, the SWOT analysis represents an indispensable analysis tool to be able to implement successful territorial development policies, able to highlight the real problems and potentialities present in an area, and therefore allow the implementing subjects to make the most opportune and convenient choices for an integrated sustainable development. In this context, the choice of this analysis model arises from the need to consider, in an integrated and coordinated way, the various aspects that are intertwined on the local scene, examining in detail each profile, in order to outline a general reference framework that offers the insights and knowledge materials necessary to propose intervention policies capable of effectively impacting local development problems.

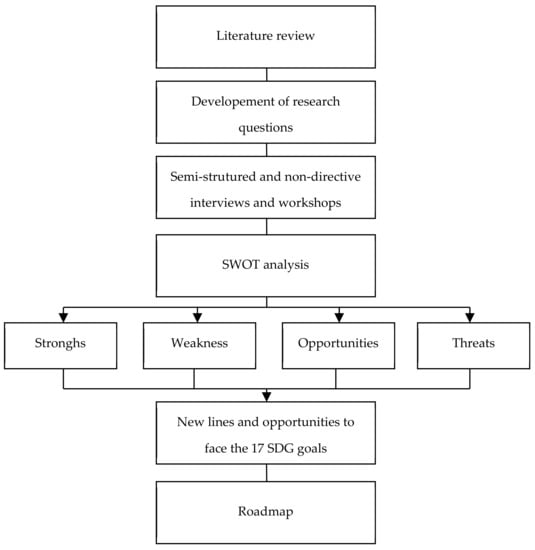

The SWOT analysis is a qualitative study in nature and has different usages in different fields, such as marketing [40], agricultural development [41], health [42], etc. It is related mostly to semi-structured interviews with experts. Since it is possible for the experts, actors and stakeholders to offer diverse interpretations with respect to the same subject, numerous interviews (individually or in a group) and workshops have been held, with a considerable number of experts, key actors and stakeholders involved in the Tunisian olive oil sector; in particular, the certified olive oil value chain, and into different projects context that tackle the olive oil value chain from different point of views, like the creation and promotion of GI labels, the responsible investment opportunities in the olive oil sector, the economic valorization of olive genetic resources, and the enhancement of olive oil value chain through the by-products valorization (Table 1). Furthermore, this approach has been supported by a literature review of the existing studies and secondary resources that tackle the actuality of olive oil sector in Tunisia and its perspective, due to scarce data and documents related to our objective (Figure 3). This step has been crucial to develop the research questions, and for the effective and good progress of the interviews and workshops. Finally, the results of the SWOT analysis represent the main inputs and the basis of the definition of a roadmap able to promote the sector of geographic indications of Tunisian EVOO locally and abroad, and to overcome the new challenges representing the 17 SDGs.

Table 1.

Expert profiles interviewed and research and development projects context.

Figure 3.

Research methodology structure adopted.

3. Results and Discussions

In order to strengthen the Tunisian market position of EVOO, both locally and at an international level, a new promotion strategy should be implemented, involving principally EVOO protected by geographical indications. Therefore, an in depth analysis aiming at understanding the current global climate of Tunisian olive oil sector, on one hand, and the potential of EVOO value chains protected by geographical indications, on the other hand, was carried out. Then, as mentioned before, a comprehensive SWOT analysis was carried out, and the results are presented in the next table (Table 2). The SWOT analysis continuously reviews all the stages of EVOO value chain, from the olive growing to EVOO product packaging, and the marketing steps. The results started by presenting the barriers and obstacles that the actors of the olive oil sector, in particular the local GI producers, could be facing, and later by identifying the advantages, and the opportunities that could be taken to promote the sector. Furthermore, the institutional, organizational, and financial frameworks describing the environment of the EVOO value chain protected by geographical indications have been reviewed.

Table 2.

SWOT analysis results for GI olive oil chain value in Tunisia.

3.1. Better PDO or PGI or Organic Certification for Tunisian Extra Virgin Olive Oil?

The challenges that witnessed the olive oil trading market in recent years made it even more difficult to maintain the competitiveness of small size producers; either farmers or olive millers. Taking into account the results of SWOT analysis and product labelling, in fact products protected by GIs could be an effective way to promote olive oils with a demonstrated mark of distinctiveness and to create an effective socio-economic dynamics, especially in continental areas, which are the most vulnerable areas in Tunisia, but present a potential to produce such kinds of particular olive oils. Since Cei et al. (2017) [24] view who assessed the Italian experience with Geographical indications and its impact on rural development of Italian regions, that the GI representing instrument to foster rural and territorial development and overall have a positive effect on agricultural value-added providing evidence of the European policy on rural development. Furthermore, in line with Riccheri et al. (2019) [44], the principal motivation to protect product specifications has been economic, to define a market niche linked to traditional and local production methods, and to obtain a price premium for the protected product. This will encourage more attention to the quality, the traceability, and the identity of the products. However, the impact of GI likely varies across countries and between products, and as argued by Cerkia (2011) [25], it is worth noting that the socio-economic dynamics of GIs are highly context specific. Therefore, the question which needs to be asked is how best to obtain the greatest benefits from the GIs, in Tunisian context? What is the most suitable for the Tunisian case at this stage, to adopt PDO or PGI strategy?

The concentration of modern infrastructure, investments and access to markets in coastal areas will make it difficult to upgrade the practices, equipment and human resources. It is then worth concluding that, at a first stage, it is important to promote exchanges between coastal main producing/transforming areas and continental areas that are just starting to modernize their means of production. Thus, it can be more efficient for the Tunisian context to promote geographical indications that involve both geographical areas in the same scheme of development. For this reason, it may be more reasonable to encourage the implementation of PGIs instead of PDOs with relatively large areas of production, in order to increase opportunities of valorization and ensure their success counting with both the initiative of local stakeholders and other operators with more capabilities. The operators could invest in the producing areas or, at least, carry out part of the process there. This could help to create a win-win situation, where new opportunities of inclusion are provided to less advantaged rural populations and give the traditional operators new innovative marketing tools responding to the coming challenges that the sector will face.

Many GIs products contribute to national identity and to cultural and gastronomic heritage, as argued by Agostino et al. (2014) [27], and further have an impact on country exports and appeal. However, a more comprehensive business model can be adopted around the GIs with a long-term vision, taking into consideration the sustainability of the economic activity, the environment, and the availability of resources [45]. As commented by Riccheri et al. (2019) [44], few GI products were explicitly set up with the motivation to protect the local environment and to preserve the local resources. It is also worth mentioning that several changes in consumer ethics and marketing philosophy may emerge in a post-pandemic context most likely toward more responsible and prosocial consumption [46]. This hypothesis can be the source of a stable economic benefits from PGIs trade if the adequate information, continue to be provided, to consumers to make the good choice during their buying decision process, as well as, if an effective verification and controls of producers carried out to eliminate unfair practices [47].

Consequently, it is important to capitalize on the organic labelling, as to be the leading brand of the Tunisian olive oil, in order to increase the added value and distinctiveness. According to Ben Abdallah et al. [4], olive-producing areas in Tunisia are composed by 81.8% of traditional conventional systems, using nearly organic practices, 13.6% of traditional certified organic systems, while only being 4.6% of intensive and super-intensive systems. This will also need additional efforts of the local producers to adhere to certification scheme, in order to be in line with local and EU legislation and traceability requirements. The combination of PGI and organic certifications could be an important asset to provide more valuable arguments in the market. Therefore, the promotion of PGIs as a sustainable economic model for Tunisian olive oil producing sector could be of great relevance, taking into account all the particular characteristics mentioned above. Moreover, the territorial developing approach can be increasingly important in the future to respond to several challenging issues of societies, especially in countries like Tunisia. Agriculture could then be an example for other goods and services to preserve the sustainability of the production systems and the cultural heritage [48,49]. Such a step would consolidate cooperation between medium size and small size stakeholders, taking advantages from the know-how of all operators, protect the identity of the product in the areas with poor access to the same know-how, and provide a sustainable scheme for territorial development in Tunisia. Moreover, the implementation of an efficient control scheme will need to provide training and education of the stakeholders from disadvantaged areas by accessing modern technology and infrastructure. Actually, the fact that an olive oil is certified as PGI does not mean systematically an insurance of a better quality if analytical and bio-analytical tools are used to control the traceability [50]. As mentioned before, trust and good knowledge of the product specifications are important drivers for consumers, since they reduce complexity and uncertainty when it comes to making a purchasing decision [16,50]. It is expected that information, technological and know-how change through this horizontal model will help to ensure more visibility to the regions and promote their access to the international markets on the long term. According to Hajdukiewics (2014) [47], historically, GIs in general have been used in international trade to gain position and profitability by conveying a certain quality or reputation based on specific geographic contexts and origin of each product. At the same time, this will help to diversify the market by introducing new authentic products as a result of the specific climate and varietal assortment in particular areas of Tunisia [51]. In order to take the maximum advantage from the new business model, PGI producers must constantly develop their skills in terms of production and mainly in marketing, beside meeting certain pre-conditions. Furthermore, the easy change and matching roles between actors horizontally and vertically through the EVOO value chain, and between areas, taking into account the new business model, will ensure the distribution of value-added among supply chain actors, as argued by Giannoccaro, et al. [52]. After establishing the basis of a sustainable partnership within the olive oil sector in Tunisia through PGI creation, other labelled products may emerge under more localized conditions, including the introduction of amendments to the product specifications when an appropriate level of maturity is reached. The specification amendment in already registered GI products is actually a common procedure in other countries [53], which allow the sustainability of the economic activity linked to each product.

The following Table 3 provides a concise analysis of the different aspects embedded in the creation of a PGI for Tunisian olive oil, according to the SDGs.

Table 3.

PGIs for Tunisian olive oil and SDGs.

3.2. Roadmap to Achieve More Sustainable PGI for EVOO Value Chain in Tunisia

As mentioned above, the olive oil sector in Tunisia represents a strategic sector and exportations constitute an obvious source of foreign currency income that enhances Tunisian economic balance. However, its contribution could be much broader and improved. In fact, a significant part or almost all of Tunisian olive oil was exported in bulk, and the exported bottled olive oil does not exceed the 10%, in average, of total olive oil export, so far to FOPROHOC objectives (i.e., 20% of total olive oil exports) [2]. Based on the SWOT analysis results, amongst other things, this could be due to:

- The competition is very tough on the international market;

- The price production of olive oil is getting more and more higher;

- Due to the lack of high-end packaging manufacturing in Tunisia, the majority of exporters import packaging, hence impacting the very high price of bottled oil;

- The destinations of the conditioned products are very distant and generate high freight costs;

- A weak national strategy to promote the Tunisian olive oil abroad and do not fit the different actors needs of the sector;

- A weak negotiating capacity with UE legal part to improve Tunisian contingent rate, etc.;

- The absence of Tunisian olive oil protected by geographical indications in international markets;

- Weak attempts to differentiate the olive oil and to limit specific requirements to protect their geographical indication.

Conversely, the Tunisian organic olive oil is booming and has reached a maturity level that allowed it to achieve a better positioning internationally and to conquer new markets, promoting Tunisia as an economic and tourist good destination, where the organic method reflects cultural aspects. In 2015, The Tunisia organic olive oil reached 95% of total exported bottled olive oil. To the best of our knowledge, the organic olive oil is the only Tunisian certified bottled olive oil marketed abroad.

Therefore, taking into account the significant potential of organic olive oil, associated to protected geographical indications, it could represent a new concept model in Tunisia to develop more efficiently the sector of olive oil and to organize it, hence to promote the Tunisian producing regions, such as the North West of Tunisia, by gaining more attention and more added values. In fact, the product differentiation principle ensures to actors a strong bargaining power and, consequently, a higher margin, awarding higher attractiveness to this segment.

To reach this objective, a reliable roadmap to produce and promote olive oil value chain protected by geographical indications, taking into account the local potential of organic products, is crucial. This roadmap should be structured and focused in five strategic axes:

- Organizational and institutional framework;

- Improve capacity building;

- Communication and networking roles;

- The role of TIC in taking new opportunities and information availability;

- Financial products and supports availability to promote distinguishable olive oil value chain.

3.2.1. Organizational and Institutional Framework

Taking into account the strategic position of the olive oil sector in the national economy and related socio-economic added value, Tunisia has opted for a strategy aiming to promote the sector oriented to give more attention to bottled olive oil exports toward their habitual market like EU, and by identifying new emerging markets like the USA, Japan, China, etc. This strategy has been supported by the presence of a complicated institutional and organizational framework counting on several public and para-public entities, as well as various professional, inter-professional and trade union organizations that interfere directly or indirectly [43,54]. For example, we can cite:

- Ministry of agriculture,

- Ministry of industry and technology,

- Trade ministry

- National oil office (ONH)

- Olive Institute

- The technical center for organic agriculture (CTAB)

- Agricultural investment promotion agency (APIA)

- Industry and innovation promotion agency (APII)

- The export promotion center (CEPEX)

- The technical center for packaging (PACKTEC),

- Other governmental and non-governmental organisms, etc.

In addition, an ecosystem has been placed to support olive oil exports. In fact, various programs have been created; the most important ones are the export market access fund (FAMEX) supported by trade ministry and financed by the World Bank, the export promotion fund (FOPRODEX) and the fund for the promotion of packaged olive oil (FOPROHOC), which represent financial support mechanisms to the actors [54]. The mentioned three programs aim to promote bottled olive oil export and the identification of the new emerging markets and to support actors to implement appropriate marketing strategies.

However, it is quite clear that the results were so far to expectations, due principally, on one hand, to the fact that the roles, missions and responsibilities of the different entities representing the institutional and organizational framework are often lacking in precision, overlap and lack overall the consistency and coordination between them. On other hand, the promotion actions and support activities proposed do not fit exactly the value chain actors’ needs involving PGI.

Consequently, it is important to sustain the Tunisian institutional and organizational framework by:

- Defining the role of different stakeholders involved in the olive oil sector as in the promotion of bottled olive oil export, their missions, and responsibilities.

- Mapping the different stakeholders in function to different phase of product’s life cycle, as well as it is important to define the technical and financial products and services purposes present in each level and who proposes it.

- Create a policy dialogue about the potential added value that presents various vulnerable and marginalized zones, such as the North-West of Tunisia, to improve policymakers’ awareness.

- Implement effective and inclusive multi-stakeholders and multi-institutional platforms to provide value chain actors, especially in marginalized zones, with the opportunity and the space to communicate their needs and priorities and give them the chance to engage directly with policymakers.

- Support initiatives, in the context of a participative approach, aiming to differentiate the quality of extra virgin olive oil products by recognizing the geographical authenticity and to valorize it by developing the technical specifications and the legal framework of the appropriate label.

- Designing a new diplomatic framework to accomplish with national policy goals.

- Improve the legal and institutional frameworks to enhance international market access and the market development strategy based on customers’ preferences knowledge.

- Create the necessary framework to assess and control the operational requirement processes to promote the bottled olive oil export.

Furthermore, recognizing the strategic role of the olive oil sector and the potential added value associated to each product in the context of gourmet products markets, especially resulting from wealth of the vulnerable zone, such as the North-West of Tunisia, the promotion of differentiated quality of the olive oil by involving geographical indication for example, and the improvement of territorial and socio-economic impacts has been the goal of different projects. These projects have been carried out by international organisms of technical and financial supports like FAO, GIZ, World Bank, ONUDI, etc. into bilateral and multilateral cooperation. However, it is important to mention that, on one hand, the results, lessons and consequences of these various projects are not documented and brought to the attention of different actors of the local olive oil value chains. On the other hand, we can easily observe the lack of harmonization and coordination between almost of these different interventions. Therefore, it is necessary to harmonize these interventions, as well as these interventions and national strategies to promote the olive oil with high added value [55]. Furthermore, it is primordial to centralize the information relating to the opportunities resulting from these projects, and to capitalize the experience and lessons revealed, which can be only a shortfall in terms of information and opportunities.

3.2.2. Improve the Required Capacity Building

Facing the protectionist policy applied by the EU, the potential export improvement towards EU lies on bottled olive oil markets enhancing, practically the certified and differentiated extra virgin olive oil such as the organic one. To achieve this objective, it is worth noting that mid- and long-term capacity building activities related to technical and marketing issues are necessary, in favor of the different actors involved in bottled and certified olive oil value chains, especially in marginalized zones. In fact, these vulnerable and marginalized zones have been interested by an olive oil sector that was not well structured, and with a high potential wealth suitable to differentiate the olive oil. Furthermore, it is important to point out that the national and sub regional institutions and stakeholders need assistance and capacity building in terms of international markets access, use appropriate marketing practices and marketing strategies implementation, and to meet international food security standards. Therefore, for this purpose, a series of recommendations could be adopted to define an excellent building capacity plan:

- Enhancing different actors’ skills involved in new PGI olive oil value chain, at various levels, to be able to manage and produce olives and olive oils with higher added value in term of socio-economic, environmental and nutritional dimensions.

- Improve actors’ awareness to respect the specific and operational requirements to produce a distinguishable olive oil able to be competitive in new emerging markets known by their higher added value, such as Australia, Japan, the USA, etc.

- Develop actors’ marketing skills to be able to promote differentiated olive oil and to increase significantly the market share of bottled extra virgin olive oil in habitual markets and to penetrate new markets. This marketing skills improvement could be related to packaging, pricing, communication, and product positioning strategies.

- Develop skills and capacities of national institutions involved in the olive oil sector to diagnostic, prospect and open new markets able to absorb the certified and differentiated extra virgin olive oil products and, therefore, to generate added value.

- Develop skills to define and support appropriate traceability mechanisms in order to better promote the Tunisian quality of olive oil.

- It is worth noting that the national authorities should be informed and up-to-date with respect to general international norms in term of food security and the specific ones attributed to targeted markets, and the internal regulation associated to olive oil sector and the legislations for geographical indications protection. This is necessary to be able to adapt the exported quality of olive oils, and the specific national legal framework aims to certify olive oil with markets requirements.

- Improve the extension services’ skills to accompany and control the actors involved in PGI olive oil value chains to respect the specific requirements to produce the suitable quality.

- To initiate an integrated and participatory research-training-extension approach based on the establishment of an interactive platform where farmers, millers, and the different actors can express freely their problems and propose priority actions to be carried out and discuss innovative solutions for a more sustainable certified olive oil value chain.

- Offer training sessions to different actors to strengthen their capacities and awareness with respect to the environmental, social and economic dimensions of new PGI extra virgin olive oil value chain.

3.2.3. Communication and Networking Roles

To develop a sustainable agri-food value chain, in particular the olive oil, we need to avoid being isolated to our environment, and in this case, networking is essential. In fact, joining a network or building one (i.e., business network), allows the members to be informed, to meet people that share the same objectives, perceptions and problems, to be up-to-date, and sometimes to discuss a distressing lifestyle in order to reassure [55]. It is a new mindset that should be considered essential in order to adapt to the new rules of territorial development and micro-economic growth.

- Improve capacity and actors’ awareness to engage with exporters, to develop their business networking and export trade intelligence.

- Revealing additional opportunities within the new PGI extra virgin olive oil value chain by shedding light on networking advantages and exchange between small actors and/or small companies.

- Stimulate actors (farmers, millers, exporters) to create an inter-professional organism or association to manage with all olive oil value chain phases and to minimize side effects, by providing immediate response and making significant efforts to control the local environmental impacts.

- Improve actors’ capacities to define and develop a successful network which could be extended to enclose national authorities such as the Tunisian chamber of commerce, national trade unions, customs, APIA, etc.

- Facilitate networking events that bring together small actors, in particularly young agri-entrepreneurs, to facilitate their access to financial products, incentives and services, and allow them to have access to all necessary information (territorial development opportunities and advantages, PGI-organic socio-economic impact and the associated added value, the business and trade opportunities, the new market niches, etc.).

- Develop events (fairs, specific exhibitions, national and local seminars, etc.) to foster collaboration and networking by regional promoters, entrepreneurs, stakeholders and actors who share common perceptions towards the development of sustainable local PGI extra virgin olive oil value chain.

- Develop a mechanism to foster and support collaboration South-North of the Mediterranean to better promote the certified extra virgin olive oil with high added value in terms of economic, environmental, and nutritional dimensions.

3.2.4. The Role of TIC in Taking New Opportunities and Information Availability

The current unsustainable olive oil production, the price volatility, the growing of olive oil global demand in the world, consumer preferences heterogeneity and their behavior change towards a sustainable environment and a more sustainable lifestyle [56], make it necessary for the olive oil sector and their involved actors to face the adoption of new economic models to take into account the new world exigencies and requirements. A good designed economic model can give actors a better understand of situation and any related problems. To this purpose, the uses of ICTs represent a glimmer of hope that seems to be looming on the horizon. The appropriate use of ICT could, in particular, optimize the obtaining, exchange and processing of the information relevant to even investment opportunities in the olive oil sector, as well as the acquisition and renewal of know-how [55,57]. To this end, a series of recommendations should be taken into consideration.

Raise actors and stakeholders’ awareness involved in bottled and certified extra virgin olive oil value chain with respect to the appropriate use of ICT tools through the implementation of a sustainable and efficient communication strategy, taking into account the profile of different actors.

- Strengthen actors’ and promoters’ skills in ICT use to overcome market isolation and improve their competitiveness in physical and virtual markets (familiarize with the new marketing tools, marketplace, e-commerce, augmented reality, etc.).

- Digitalize all information and administrative process (administrative information, legal information, the different financial sources, the prices evolution, the production tendency, new market characteristics, etc.).

- Use ICT tools appropriately and understand the opportunities presented to overcome the challenges that actors and stakeholders face to boost the PGI extra virgin olive oil value chain (competitive intelligence, market opportunities and restrictions, change and consumer behavior, etc.).

- Establish a platform that brings all programs, activities and projects carried out to promote differentiated Tunisian extra virgin olive oils and improve the real context.

- Communicate about agronomic, industrial, market, and entrepreneurial opportunities in certified and bottled EVOO value chain, and present the ready innovations with high added value, based in ICT technologies, to adopt.

- Create a multidisciplinary and multi-actor platform to communicate operational and technical services proposed by various administrations and financial structures and market opportunities’ requirements in the context of certified and bottled EVOO. In fact, this virtual platform could be representing “one stop contact point” where the promoter can find all the necessary information valid to implement bottled extra virgin olive oil export actions.

3.2.5. Financial Products and Supports Availability to Promote Distinctiveness Olive Oil Value Chain

As mentioned before, the olive oil sector represents one of the principal pillars of the Tunisian economy. It is a strategic sector due to socio-economic, nutritional and environmental dimensions, thus associated to comprehensive financial and fiscal incentives framework to promote the sector in general and the bottled olive oil export, in particular. Furthermore, Tunisian presents a solid banking infrastructure, including public and private banks, and microfinance institutions [54,57]. However, the lack of suitable financial products and incentives able to stimulate the actors and promoters to invest in the sector, mainly in differentiated olive value chains, represents one of the principles limits [57]. Therefore, it is vital to take into consideration the next suggestions:

- Assess the performance and the efficiency of financial products and supports that already exist to promote bottled olive oil export and olive oil quality differentiation, and to measure the acceptability of this products and services from the actors and/or promoters.

- Carry on an analysis of actors’ and promoters’ demand of financial products and kind of supports which need to better promote PGI extra virgin olive oil value chains and to be more competitive with respect to their international direct competitors.

- Propose a new kind of support or adapt the existing ones to actors needs taking into account for example price support, to define and implement appropriate marketing strategy, tax exemption to import high quality packaging to conserve olive oil quality, tax exemption to export differentiated and bottled and PGI extra virgin olive oil, support to packaging services, to participate in international olive oil competitions, etc.

- Propose tri-partite banking credits and facilities to bring together promoter-industrial-farmers for the good management of the value chain and quality control, and for the adequate territorial development.

- Support prospection programs to differentiate sustainable olive oil related to geographical, varietal, and environmental wealth.

- Define feasible financial products, incentives and services at short-, mid- and long-term, and to provide technical assistance, training, study tours, and others as building capacity supports in olive oil techniques and quality differentiation, and the good marketing tools.

4. General Conclusions

The fact that the majority of Tunisian olive oil is exported in bulk causes a lot of tension on the national economic balance; it accelerates the disparity between regions involving social, economic, and environmental challenges at both regional and national levels. Therefore, the goal of a geographical indication for Tunisia’s extra virgin olive oils is to raise the level of competitiveness of the supply chain aimed at improving: (a) the profitability of olive farms; (b) the commercial role of vulnerable actors and incentives towards new organizational forms; (c) the distinctiveness of the quality through product qualification and differentiation interventions; (d) the protection of the final product with an efficient control system; (e) the support of aggregation and coordination within the supply chain, vertically as well as horizontally, involving regulatory and economic factors, capable of inducing a more effective association [58].

In the same perspective, the main objective of the present paper is to assess, in a comprehensive way, the environment of olive oil sector in Tunisia, in particular with regards to GIs, by identifying the advantages and barriers of the value chain and, therefore, take the opportunities that are capable to bring out the territory. It is also crucial to define a roadmap able to make effective and operational GI initiatives taking into account the different dimensions of Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.

The principal output of the present paper highlights that PGI is more suitable for the Tunisian olive sector than PDO, at least at the current stage. Actually, PGI allows one to encourage connections between coastal and continental areas, counting with the initiative of local stakeholders from disadvantaged areas and operators with more capabilities coming from coastal provinces. Moreover, taking into account the position of Tunisian organic olive oil in the world, the combination of PGI and organic certifications could be an important asset to provide more valuable arguments in the markets, and therefore could be more relevant in the Tunisian context. Hence, PGI-organic extra virgin olive oil can help to create new niches able to sustainably improve the competitiveness of SME, based more on their authenticity than the volume of production [59].

However, it is worth concluding that a roadmap must be implemented in order to reach our objective and to make these initiatives more reliable. The roadmap presented in this study aims at: (a) promoting more effectively extra virgin olive oil protected by geographical indications, taking into account the local potential of organic products by providing the necessary capacity building; (b) shortening the distances between areas and between all stakeholders to achieve the different initiatives taking into consideration the goals of the 2030 Agenda in the Mediterranean basin; (c) removing behavioral and institutional barriers that inhibit the transformations needed to achieve more sustainable economies and societies; (d) creating a cross-disciplinary dialogue around the sustainability of PGI extra virgin olive oil value chain and narrowing the gap between research, policymakers, and the other stakeholders; (e) presenting the financial and support products able to help to achieve our goal according to the expectations of the actors, particularly young entrepreneurs; and (f) strengthening actors and young promoters’ skills using TIC solutions to overcome market isolation, and to optimize the acquisition of the information, its exchange and processing, in order to take opportunities for a responsible investment in the olive oil sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G., M.L.C. and A.Y.; methodology, M.F., S.G., M.L.C.; validation, F.C., P.C.; formal analysis, S.G., A.Y. and M.L.C.; investigation, M.F., M.L.C. and A.Y.; resources, A.Y., M.L.C.; data curation, A.Y. and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G., M.L.C.; writing—review and editing, A.Y., S.G. and M.L.C.; visualization, M.F.; supervision, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data reported and provided are available according to reported References.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hernández, J.V.; Pereira Benítez, J.E.; López, D.U.; Sánchez, A.M.; Bermúdez, S.C.; Pernas, J.B.; Gámez, M.V.; Puentes Poyatos, R.; Sayadi Gmada, S.; García, I.R.; et al. L’oléiculture Internationale. In Diffusion Historique, Analyse Stratégique et Vision Descriptive; Fundación Caja Rural de Jaén: La Carolina, Spain, 2018; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Home—International Olive Council (Internationaloliveoil.org). OLIVAE: Official Journal of International Olive Oil Council N° 124; Home—International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- HO-W901-23-11-2020-P.pdf. Available online: internationaloliveoil.org (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Ben Abdallah, S.; Elfkih, S.; Suarez-Rey, E.M.; Parra-Lopez, C.; Romero-Gamez, M. Evaluation of the environmental sustainability in the olive growing systems in Tunisia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exportation de L’huile D’olive en Tunisie et Suivi de Certains Marchés Extérieurs. Available online: http://www.agridata.tn/organization/direction-generale-de-la-production-agricole?organization=direction-generale-de-la-production-agricole&page=2 (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Easy Comext. Available online: europa.eu (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Akerlof, G.A. The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, S. Territorial identity and terroir. An analysis of the role of organic viticulture in the durability of rural landscapes. In Proceedings of the Conception de Systèmes de Production Agricole et Alimentaire Durables dans un Context de Changement Global en Méditerranée; 1er Forum Méditerranéen de Doctorants et Jeunes Chercheurs, CIHEAM-IAM Montpellier, France, 18–19 July 2016; pp. 5–8, ISBN 978-2-85352-571-8. Available online: https://forumciheam2016.scienceconf.org (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Bowen, S.; Muterchbaugh, T. Local or localized? Exploring the contributionsof Franco-Mediterranean agrifood theory to alternativefood research. Agric. Hum. Value 2014, 31, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschini, G.; Menapace, L.; Pick, D. Geographical indications and the competitive provision of quality in agricultural markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union, Regulation (EU) no 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. 2012. EUR-Lex-32012R1151-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: europa.eu (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- WIPO IP Portal. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/ipdl-lisbon/searchresult (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Loi n° 99—57 du 28 Juin 1999, Relative aux Appellations D’origine Contrôlée et aux Indications de Provenance des Produits Agricoles. Available online: https://wipolex-res.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/fr/tn/tn017fr.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Indication de provenance Huile d’olive de Monastir. Available online: http://www.aoc-ip.tn/images/pdf/huile-olive-monastir-IP.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- WIPO/LISBON-the International System of Appellation of Origin, Decree of Olive Oil “Zit Zittouna Teboursouk” Appellation of Origin. 2020. Available online: https://www3.wipo.int/branddb/jsp/data.jsp?TYPE=PDF&SOURCE=LISBON&KEY=NOTIF_11343.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Yangui, A.; Costa-Font, M.; Gil, J.M. The effect of personality traits on consumer’s preferences for extra virgin olive oil. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 51, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangui, A.; Gil, J.M.; Costa-Font, M. Comportamiento de los consumidores españoles y los factores determinantes de sus disposiciones a pagar hacia el aceite de oliva ecológico. ITEA-Inf. Técnica Económica Agrar. 2019, 115, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, N.; Jabri, I.K.; Sifi, S.; Abderrabba, M. Physical chemical and sensory characterization of olive oil of the region of Kairouan. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016, 7, 2148–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Bérard, L.; Marchenay, P. Local products and geographical indications: Taking account of local knowledge and biodiversity. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2006, 58, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, F.K.; Negm, A.M.; Abu-Hashim, M. Update, Conclusions, and Recommendations for Agriculture Productivity in Tunisia under Stressed Environment; Springer Water Book Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fendri, M.; Jendoubi, F.; Oueslati, H.; Mahmoud, L.B.; Khlifi, A.; Laabidi, O.; Boudhrioua, N. Évaluation de l’infrastructure de transformation dans les differents terroirs du nord de la tunisie pour la production d’huiles d’olive labelisées. Rev. Ezzaïtouna 2020, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Laajimi, A.; Ben Nasr, J.; Guesmi, A. Assessment of sustainability in organic and conventional farms in Tunisia: The case of olive-growing farms in the region of Sfax. Presented at the 12th EAAE Congress ‘People, Food and Environments: Global Trends and European Strategies’, Gent, Belgium, 26–29 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IFOAM—Organics International. The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics and Emerging Trends 2019; Willer, H., Lernoud, J., Eds.; IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.organic-world.net/yearbook/yearbook-2019/pdf.html (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Cei, L.; Stefani, G.; Defrancesco, E.; Lombardi, G. Geographical Indications: A first Assessment of the Impact on Rural Development in Italian NUTS3 Regions; Working Paper n°14; DISEI—Università Degli Studi di Firenze: Florence, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cerkia, B. A review of the socio-economic impact of geographical indications: Considerations for the developing world. Presented at the WIPO Worldwide Symposium on Geographical Indications, Lima, Peru, 22–24 June 2011; HO-CE901-23-11-2020-P-2.pdf. Available online: internationaloliveoil.org (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A.; Touzard, J.M. Geographical indications, public goods and sustainable development The roles of actors’ strategies and public policies. World Dev. 2015, 98, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, M.; Trivieri, F. Geographical indication and wine exports. An empirical investigation considering the major European producers. Food Policy 2014, 46, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONAGRI. Observatoire National de L’agriculture. La Filière D’huile D’olive en Chiffres. 2021. Available online: onagri.nat.tn (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Ferrer-Pérez, H.; Abdelradi, F.; Gil, J.M. Geographical Indications and Price Volatility Dynamics of Lamb Prices in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, D.; Monier-Dilhan, S.; Orozco, V. Measuring Consumers’ Attachment to Geographical Indications. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2011, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie Vivien, D. The Protection of Geographical Indications in India: A New Perspective on the French and European Experience; Ringgold Inc.: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2015; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Systaining Superior Performance, the Free Press: A Division of Macmillan; INC: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, A.; Ianuario, S. Environmental and social sustainability in Producer Organizations’ strategies. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1732–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commission, Farm to Fork Strategy. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Renting, H.; Rossing, W.A.H.; Groot, J.C.J.; van der Ploeg, J.D.; Laurent, C.; Perraud, D.; Stobbelaar, D.J.; van Ittersum, M.K. Exploring multifunctional agriculture. A review of conceptual approaches and prospects for an integrative transitional framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, S. Territorial Identity and Rural Development: Organic Viticulture in Apulia Region and Languedoc Roussillon. In L’apporto Della Geografia tra Rivoluzioni e Riforme; Atti del XXXII Congresso Geografico Italiano; Salvatori, F., Ed.; AGEI: Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 1901–1909. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, F. Eco-localism and sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 46, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, M.M.; Nixon, J. Exploring SWOT analysis—Where are we now? J. Strategy Manag. 2010, 3, 215–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, T.M.; Krishnan, M.; Venugopalan, R. SWOT analysis and recommended policies and strategies of eritrean fisheries. In Proceedings of the IIFET 2014 Australia Conference 2014, Brisbane, Australia, 7–11 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Velita, L.V.; Suson, J.R. Green marketing strategies for a sustainble business. J. Agric. Technol. Manag. JATM 2020, 23, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tafida, I.; Fiagbomeh, R.F. Multi-criteria SWOT-AHP analysis for the enhancement of agricultural extension services in Kano State, Nigeria. J. Dry Land 2021, 7, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cinar, F.; Eren, E.; Mendes, H. Decentralization in health services and its impacts: SWOT analysis of current applications in Turkey. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fiedler, Y. Empowering Young Agri-Entrepreneurs to Invest in Agriculture and Food Systems—Policy Recommendations Based on Lessons Learned from Eleven African Countries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccheri, M.; Görlach, B.; Schlegel, S.; Keefe, H.; Leipprand, A. Assessing the Applicability of Geographical Indications as a Means to Improve Environmental Quality in A_ected Ecosystems and the Competitiveness of Agricultural Products; Workpackage 3, Final Report; IPDEV: Paris, France, 2007; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ess/wpaper/id847.html (accessed on 16 October 2019).

- Saatcioglu, B.; Ozanne, J.L. A Critical Spatial Approach to Marketplace Exclusion and Inclusion. J. Public Policy Mark. 2013, 32, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdukiewciz, A. European Union agri-food quality schemes for the protection and promotion of geographical indications and traditional specialities: An economic perspective. Folia Hortic. 2014, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K.; Vittersø, G. Local Food Initiatives and Fashion Change: Comparing Food and Clothes to Better Understand Fashion Localism. Fash. Pract. 2018, 10, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalaglio, A.; Guerrieri, F.; Carls, S. Sui Generis Geographical Indications for the Protection of Non-Agricultural Products in the EU: Can the Quality Schemes Fulfil the Task? IIC-Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law 2020, 51, 31–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likudis, Z. Olive oils with protected designation of origin (PDO) and protected geographical indication (PGI). In Products from Olive Tree; Dimitrios, B., Clodoveo, M.L., Eds.; BoD—Books on Demand: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hassainya, J. Valorisation des Produits Agricoles Locaux du Maghreb à Travers la Labélisation; Rapport National Tunisie; FAO: CIHEAM Bari, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoccaro, G.; Carlucci, D.; Sardaro, R.; Roselli, L.; de Gennaro, B.C. Assessing consumer preferences for organic vs eco-labelled olive oils. Org. Agric. 2019, 9, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescotti, A.; Quinones-Ruiz, X.F.; Edelmann, H.; Belletti, G.; Broscha, K.; Altenbuchner, C.; Scaramuzzi, S. Are Protected Geographical Indications Evolving Due to Environmentally Related Justifications? An Analysis of Amendments in the Fruit and Vegetable Sector in the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO and INRAT. Dynamique de L’investissement dans le Système Agricole Tunisien et Perspectives de Développement des Investissements par et Pour les Jeunes; Tunisia, FAO and INRAT. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/cb0563fr/CB0563FR.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Yangui, A.; Fiedler, Y.; Elloumi, M.; Ouertani, E.; Bensaad, A. Document D’orientation n° 3: Des Informations Disponibles et Accessibles Pour un Environnement Favorable à L’investissement Responsable des Jeunes dans le Secteur Agricole et les Systèmes Agroalimentaires. Solutions à Court Terme; FAO et INRAT: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yangui, A.; Costa-Font, M.; Gil, J.M. Revealing additional preference heterogeneity with an extended random parameter logit model: The case of extra virgin olive oil. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 2, s553–s567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elloumi, M.; Fiedler, Y.; Ben Saad, A.; Ouertani, E.; Yangui, A.; Labidi, A. Pour un Environnement Institutionnel et Financier Favorable à L’investissement par les Jeunes dans L’agriculture et les Systèmes Alimentaires en Tunisie: Document D’orientation. Rome, Italy, FAO and INRAT. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/fr/c/cb0884fr/ (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Bramley, C.; Biénabe, E.; Kirsten, J. The economics of geographical indications: Towards a conceptual framework for geographical indication research in developing countries. Econ. Intellect. Prop. 2009, 1, 109–149. [Google Scholar]

- Helga, W.; Lemoud, J. The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2019; FiBL and IFOAM: Frick, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).