Re-Visiting Design Thinking for Learning and Practice: Critical Pedagogy, Conative Empathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

The search for scientific bases for confronting problems of social policy is bound to fail, because of the nature of these problems. They are “wicked” problems, whereas science has developed to deal with “tame” problems. Policy problems cannot be definitively described. Moreover, in a pluralistic society there is nothing like the undisputable public good; there is no objective definition of equity; policies that respond to social problems cannot be meaningfully correct or false […] Even worse, there are no “solutions” in the sense of definitive or objective answers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Designerly Thinking (DT), Designerly Ways of Knowing (DWK)

“Designerly ways of knowing are the cognitive approaches and mindsets characteristic of expert designers such as framing, reflection-in-action, and abductive reasoning. Design thinking strategies are the processes involved in design, including frame creation, ideation, prototyping, iteration, and deploying in real-world contexts (p. 2)”.

2.2. DT in Tourism and Hospitality Related Studies

It is possible to see visitors’ agency as operating in the co-production of meaning at a more-than-representational level: meaning is conceptualized as generated, explored and shared in all manner of ways, drawn as it is from memories and preconceptions, the narratives of overarching discourses and not least the somatic nature of engagement and the emotional.[35] (p. 97)

2.3. Decolonizing DT, Fascilitating Plutalism and Rationality

The model effectively integrated key values and identities of the Indigenous culture which led to additional benefits and outcomes for the Lacandon co-researchers including the revitalization of cultural knowledge.[38] (p. 1341)

enrich visitors’ experiences with their unique symbolism and cosmology of the landscape and furthermore to share their own story on their own terms. Furthermore, through learning and sharing experiences, visitors become knowledgeable about Indigenous issues and concerns, helping them become more respectful tourists and helping advance the political agenda of Indigenous peoples.[38] (pp. 1344–1345)

3. Case Example: Pandemic Experiences and Reflections through Creative Writing

In the left-hand corner of my picture is the back of myself holding my phone, it then shows images stacked on top of themselves. The image of the stacked images is my view of what I have seen through social media the last several months…For me each of these images hit home, it showed me the impact that we as people have on the world. The pollution that we cause, the over tourism, the negativity we create, COVID-19 created in my mind a break. The entire right side of my creation is my personal perceptions and experiences during the quarantine and now coming out of it…a stack of books reflects the required text books I have been reading for my summer classes, the end of Spring semester readings, and personal reading choices, as well as my journal that I write in regularly. Crafting is another way that I release my emotions and for me this entire quarantine created a lot of mixed feelings, which the paint brush and canvas image represent. Finally, across the center of my image words reflecting what the world seems to be screaming at me every time I look. “Breaking News”, “Riots”, “COVID-19”, “Protests”, “Small Businesses Failing”, all words that I can’t escape, each telling someone else’s story, each with a vast set of emotions, each seeking attention. (Student’s one-paragraph description accompanying the drawing).

My drawing depicts my personal experience and perception of COVID-19. I have created a piece that represents the concept of “flatten the curve” which is the reason for self-quarantining and social distancing going into effect. In my drawing, the straight lines represent how life was on a steady trajectory until the pandemic hit. The “flatten the curve” graph can be seen within the piece as well as heart rate depictions. The heart rate depictions are to represent the amount of people who sadly have been hospitalized due to Coronavirus and the uncertainty of the virus causing nervous and racing hearts. The background colors are a blend of yellow and green to represent sickness. Together the piece speaks to the core concept of doing your part for the good of humanity. By everyone self-quarantining and social distancing we can slow the spread of COVID-19 to prevent the shortage of hospital resources. Personally, I believe that to “flatten the curve” means to do your part to keep everyone safe and that is what inspired my drawing. (Student’s one-paragraph description accompanying the drawing).

When I read over the subject for this writing assignment, several ideas flowed through my head. I thought to myself, “Perfect, this is my time to vent about how difficult it has been transitioning from in-person to online classes.” Then I thought about all the other students and professors that might feel the same way and will probably write about it. I, then, briefly thought of writing about how difficult this quarantine has been for my family, especially my younger brother who struggles with mental health issues, but I figured it was too personal. The effects this quarantine has had on the environment came to my mind. I reflected on all of the photos and news articles I have seen and read about how much cleaner the canals in Venice are, the beaches in the west coast, the pollution levels dropping all across the world, but I could not figure out how to write about it all in my own words without restating what everyone else has written. So, I finally decided to just write about me and what I have been up to in the last few months during this pandemic.

In my drawing for this assignment I have split it up between two different times of this quarantine. The first half I drew what my life was like during the beginning of the quarantine. I sketched out myself and my roommate, Stephen, sitting in our living room watching TV while drinking wine and eating pizza and popcorn. That is pretty much all we would do every single day for the first few weeks of the lock down. Neither one of us was very productive and we had hit a very low low in our lives. The second half I sketched myself out sitting on the same chair as the first photo, however instead of being on my phone I am reading a book, have the TV off and instead of a glass and bottle of wine next to me I have my water bottle. Below that sketch I drew myself running through Lemon Creek Park because I like to run through there during my morning runs. These sketches show how much my habits have changed throughout these past few months of the pandemic. (Student’s one-paragraph description accompanying the drawing).

It was mid spring break when I found out we would not be returning to regular classes for the remainder of the semester. That same week I found out I was being furloughed. I did not know how I felt or what to make from the whole situation. All I could think about was, ‘How am I going to pay for all of my bills?’

I drew a picture of a women meditating in the center of the Earth. Meditation is all about relaxing and focusing on the things that you can and cannot control. The women in the middle represent me and my personal journey with COVID-19. The recent pandemic has altered my life in many ways including my social life, my school and career, and has left many uncertainties. However, it has also helped me grow in ways I would not have imagined. That is what this picture represents to me. (Student’s one-paragraph description accompanying the drawing).

The drawing I drew is called Covid Good Covid Bad, and it represents the duality of the situation we are in. There has been unprecedented damage, destruction, and death that has come because of Covid-19. The bad things represented are death, by the skull and crossbones, fear, represented by the mask, cancelled trips and plans, represented by the suitcase, a world that has been hurt, represented by the globe, the separation from society, represented by the people separated by the letters of Covid-19, and the collapse of industry, represented by the falling dominoes. The good things are time, represented by the clock, personal growth, represented by the paintbrush and music notes, rest, represented by the pillow, relaxation, represented by the cup of tea, and most importantly family, represented by the family. Even in the midst of the chaos of corona, there are good things we can put our focus on. That’s what I hoped to capture with my drawing. (Student’s one-paragraph description accompanying the drawing).

Overall, my drawing is meant to experience the joy I find in my daily life, for example, looking up in the sky during the day or the night to see the sun or the stars and realizing that life is truly a gift. My thoughts and the outside world may seem as if though they were really negative but I have been taking a lot of important things to me for granted. I have realized more that I have a lot of love and compassion for other people and that honestly, that it almost feels rare. I have surrounded myself with friends and family and reconnecting with those I truly care about. The uncertainty of everything is difficult for me to deal with but I am trying my best. (Student’s one-paragraph description accompanying the drawing).

4. Directions Forward: Design for Critical, Empathetic “Doing” DT

4.1. A Relational Approach towards Conative Empathy

challenges universal principles about how we should act and behave, and instead, argues for a relational form of care ethics, wherein caring and responsibility are framed as reciprocal, and deeply embedded in our personal commitments to others (Gilligan, 1982. Furthermore, the intimacy of caring creates bonds that foster relational ecologies, characterized by empathy, trust and equity”.[39] (p. 129)

4.2. Implementing the Theoretical into Practice

- (i)

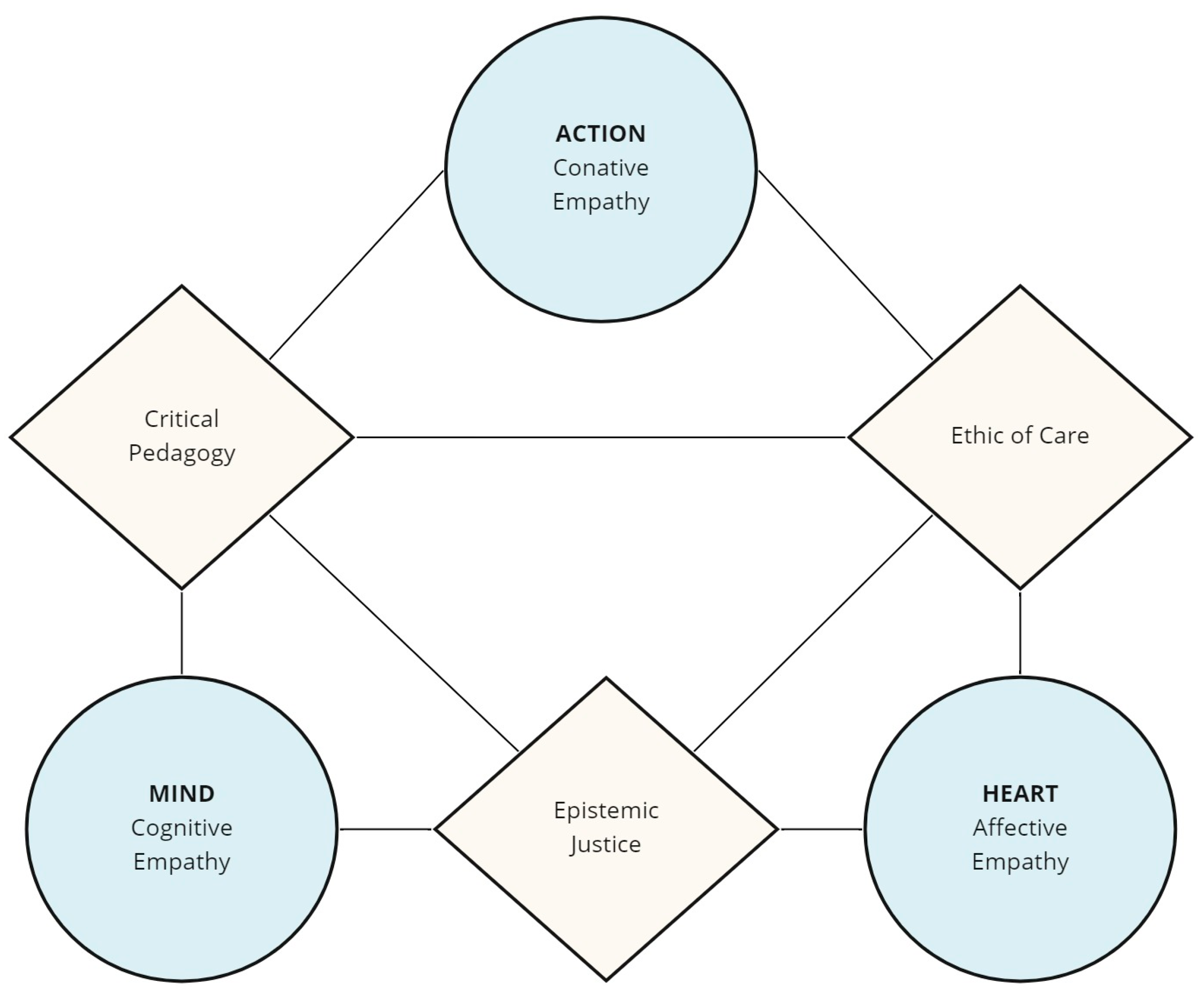

- Diverse designerly ways of knowing (DWK) which embrace pluralistic worldviews and values. In other words, to address inclusivity not merely in terms of collaborative co-creation but also epistemically with respect to diverse ways of knowing, doing, and becoming, and to outcomes enabling equity and justice.

- (ii)

- Diverse process-oriented approaches to design thinking (DT) that foster relationality and embody affectively values in the practice and implementation of DT, i.e., empathetic engagement with learning in action. Here, empathy is not merely cognitive (in the mind) nor merely affective (i.e., emotions and feelings tugging at the heart), but also conative through acting empathetically (in learning and practice).

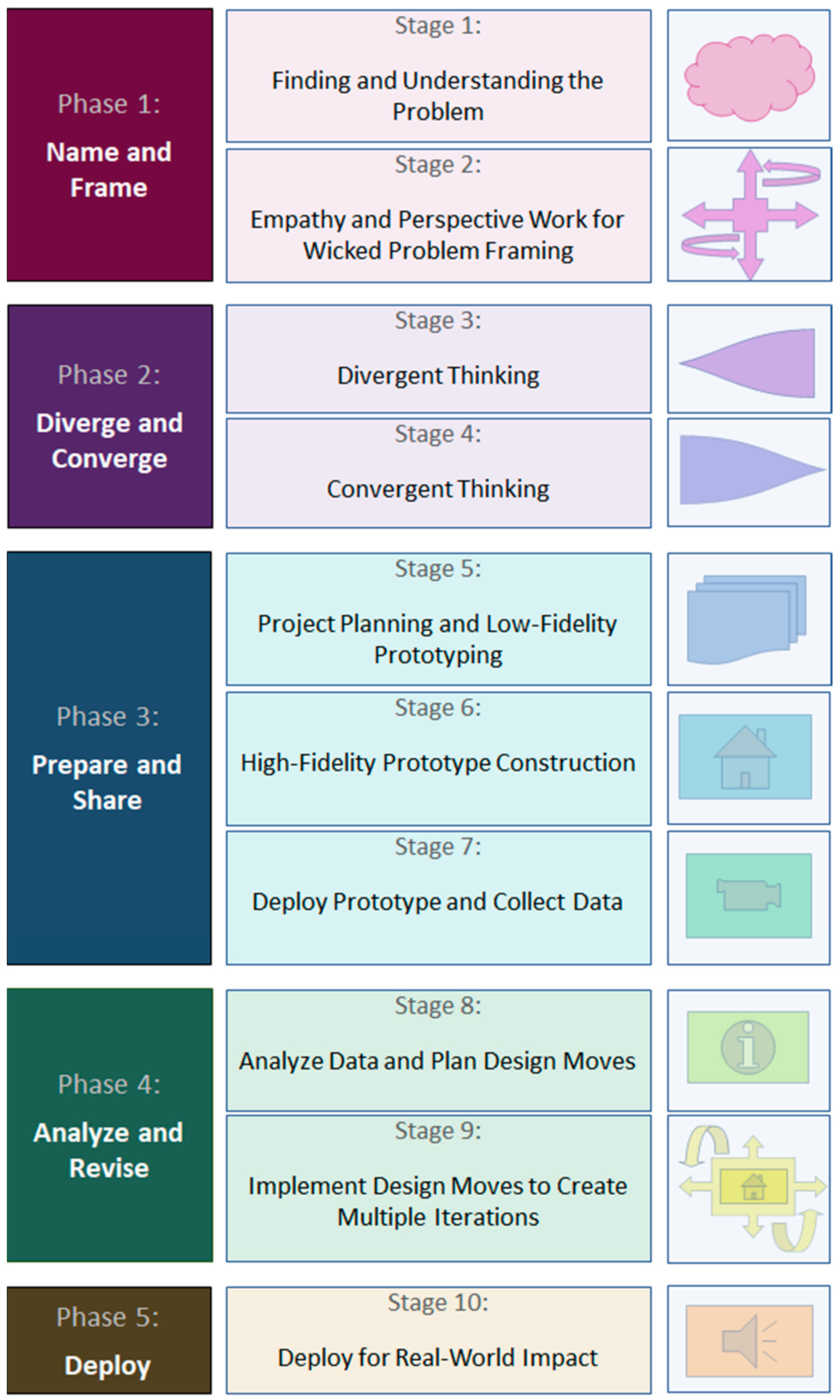

4.3. Re-Envisioning Design Thinking for Engaged Learning

4.4. Design Thinking Process in the Revised DTEL Model

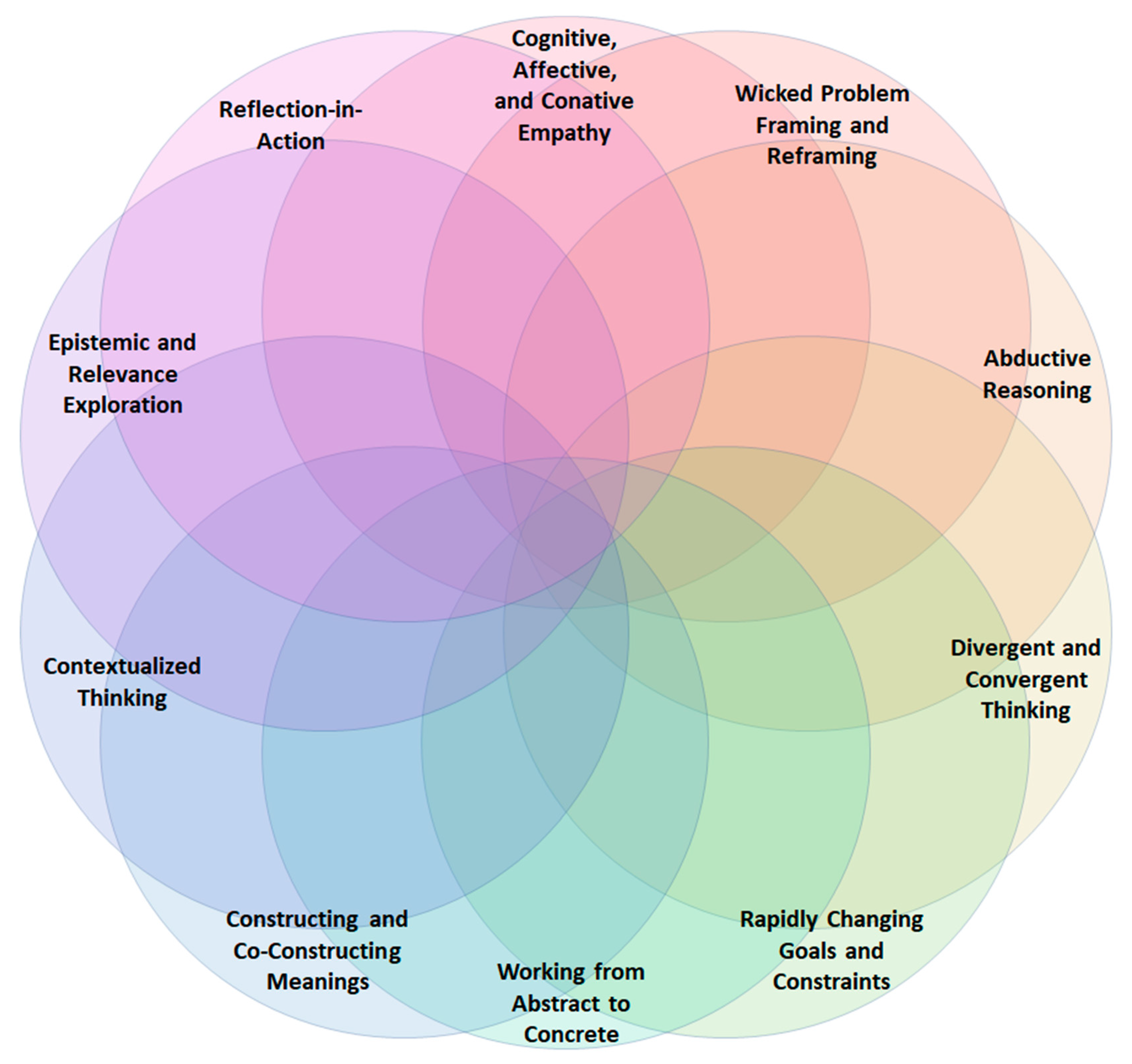

4.5. Designerly Ways of Knowing in the Revised DTEL Model

5. Conclusions

- Community-based Collaborative Research for CBT, social enterprises, and businesses must orient design thinking approaches towards community driven design vs. externally imposed top-down design (for more on community-driven development, see [69]). Co-creation—creating co-value as co-equals between visitors and community members—is one aspect, but co-ownership, inclusiveness, and co-involvement in the design of the prototype is crucial if epistemic justice in DWK and communal well-being is to be achieved through the DT process.

- Working as co-equals with others in the community and having equal ownership with the designer(s) means being involved right at the start of the DT process, developing the problem, framing, making up the questions, etc. If students are doing the project through DTEL, for instance, then students (designers) must work with resident communities and visitors early in the design process to enable a “decolonizing” approach that is fair, equitable, and pursues epistemic justice.

- Critical pedagogy and praxis as per Freire [48] are simply not sufficient, however, as argued above. Going beyond cognitive empathy, design thinking approaches must include an ethic of care and embodied empathy as illustrated by the terms conative empathy in our theoretical framework (Figure 7), in order to facilitate critical action towards inclusiveness, equity and fairness (Figure 7)—advancing communal well-being, resilience and planetary sustainability through just transitions and pluralistic justice in the Anthropocene (see also [70] for more on co-designing for sustainability in tourism);

- Recent emerging post-structural critiques and post-humanist perspectives on affective hospitality may help to further develop pluralistic, relational, non-dualistic approaches to DTEL and DT that advance posthumanistic design and caring for people and caring about non-human others (animals and other living things, place and social-ecological systems) (e.g., [56,57,71,72,73]. As Phi and Dredge [33] point out in their special issue on co-creation:The Anthropocene demands that we de-centre our human perspective, to exercise empathy and to acknowledge the rights of Nature. Co-creation has an enormous contribution to make in this regard, because it implores us to think about the co-design, co-creation and co-production of tourism with Nature, and not simply as based on, or exploiting, Nature [33] (p. 283);

- Drawing on cross-disciplinary areas such as the Learning Sciences, and sources like the Journal of Learning Sciences, offer valuable guidance to enable transformative learning experiences and relational praxis, engaging situated standpoint epistemologies and pluralistic knowledges in affective, human-centered design to enable epistemic justice and responsible practice [74,75].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). COVID-19 Response. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-covid-19 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Buhalis, D.; Yen, E.C.S. Exploring the Use of Chatbots in Hotels: Technology Providers’ Perspective; Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Koo, C.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z. Special issue on smart tourism: Convergence of information technologies, experiences, and theories. Electron. Markets 2015, 25, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Guarino, P.A. Work and unemployment in the time of COVID-19: The existential experience of loss and fear. J. Hum. Psychol. 2020, 60, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Design thinking. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Razzouk, R.; Shute, V. What is design thinking and why is it important? Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, C.B. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. Starting at Home: Caring and Social Policy; Univ of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N. Designerly Ways of Knowing; Springer: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, J.P.; Smith, B.K. Design thinking, designerly ways of knowing, and engaged learning. In Learning, Design, and Technology: International Compendium of Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; De Leon, N.; George, G.; Thompson, P. Managing by design. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, F.J.; Krizaj, D. Experiences through design and innovation along touch points. In Design Science in Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N. Designerly ways of knowing: Design discipline versus design science. Design Issues 2001, 17, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd ed.; Herbert, A.S., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dorst, K. The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Des Stud. 2011, 32, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEO. Design Thinking for Educators; IDEO: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sándorová, Z.; Repáňová, T.; Palenčíková, Z.; Beták, N. Design thinking-A revolutionary new approach in tourism education? J. Hosp. Leisure Sport Tour Educ. 2020, 26, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Donald, A.S., Ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. On the essential contexts of artifacts or on the proposition that design is making sense (of things). Design Issues 1989, 5, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.B.; Everett, J. Resisting rationalisation in the natural and academic life-world: Critical tourism research or hermeneutic charity? Curr. Issues Tour. 2004, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S. Design thinking in hospitality education and research. Worldwide Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, G.; Chung, D. WOW the hospitality customers: Transforming innovation into performance through design thinking and human performance technology. Perform. Improv. 2018, 57, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.D.; Costa, R.A.; Pita, M.; Costa, C. Tourism Education: What about entrepreneurial skills? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 30, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lub, X.D.; Rijnders, R.; Caceres, L.N.; Bosman, J. The future of hotels: The Lifestyle Hub. A design-thinking approach for developing future hospitality concepts. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliñski, G.; Studziñska, M. Application of design-thinking models to improve the quality of tourism services. Zarzdzanie i Finanse. J. Manag. Finance 2015, 13, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Piancatelli, C.; Massi, M.; Vocino, A. #artoninstagram: Engaging with art in the era of the selfie. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, G.; Çelebi, D. A Social Media Framework of Cultural Museums. AHTR 2017, 5, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altukhova, N.F.; Vasileva, E.V.; Gromova, A.A. Design thinking in the marketing research on tourism experience. In Design Thinking in the Marketing Research on Tourism Experience, Financial and Economic Tools Used in the World Hospitality Industry: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Management and Technology in Knowledge, Service, Tourism & Hospitality 2017 (SERVE 2017), Bali, Indonesia; Moscow, Russia, 21–22 October 2017; 30 November 2017; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, S. Service design: New methods for innovating digital user experiences for leisure. In Industrial Engineering: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Phi, G.T.; Dredge, D. Collaborative tourism-making: An interdisciplinary review of co-creation and a future research agenda. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, G.; Dredge, D. Critical issues in tourism co-creation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, L.; Lupetti, M.L.; Khan, S.; Germak, C. Ethic reflections about service robotics, from human protection to enhancement: Case study on cultural heritage. In Robotics-Legal, Ethical and Socioeconomic Impacts; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schorch, P.; Waterton, E.; Watson, S. Museum Canopies and Affective Cosmopolitanism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Designs for The Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and The Making of Worlds; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, R. Book Review: Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Lincoln Plan. Rev. 2019, 10, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Espeso-Molinero, P.; Carlisle, S.; Pastor-Alfonso, M.J. Knowledge dialogue through indigenous tourism product design: A collaborative research process with the Lacandon of Chiapas, Mexico. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1331–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T. Justice and Ethics in Tourism; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge, D.; Meehan, E. Street Voices. In Justice and Ethics in Tourism; Jamal, T., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Reborn-Art Festival 2019: An Inspired Event For Tohoku Earthquake Recovery. Available online: https://matcha-jp.com/en/7740 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Krippendorff, K. The Semantic Turn: A New Foundation for Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen, D.A. Educating for reflection-in-action. In Planning for Human Systems: Essays in Honor of Russell, L. Ackoff; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Norlock, K. Feminist Ethics. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-ethics/#Bib (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Sander-Staudt, M. The unhappy marriage of care ethics and virtue ethics. Hypatia 2006, 21, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noddings, N. Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Tourism CoLab. Available online: https://www.thetourismcolab.com.au/ (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Bloomsbury publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schramme, T. Empathy in Ethics; Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sakr, M.; Jewitt, C.; Price, S. Mobile experiences of historical place: A multimodal analysis of emotional engagement. J. Learn. Sci. 2016, 25, 51–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vortherms, K. Engineering Empathy; University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vossoughi, S.; Jackson, A.; Chen, S.; Roldan, W.; Escudé, M. Embodied pathways and ethical trails: Studying learning in and through relational histories. J. Learn. Sci. 2020, 29, 183–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, K.D.; Jurow, A.S. Social design experiments: Toward equity by design. J. Learn. Sci. 2016, 25, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klahr, D. Learning Sciences Research and Pasteur’s Quadrant. J. Learn. Sci. 2019, 28, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W.R. Infrastructuring as a practice of design-based research for supporting and studying equitable implementation and sustainability of innovations. J. Learn. Sci. 2019, 28, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, L.H.; Hall-Wieckert, M.; Lim, V.Y. Making space for place: Mapping tools and practices to teach for spatial justice. J. Learn. Sci. 2017, 26, 643–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guia, J.; Jamal, T. A (Deleuzian) posthumanist paradigm for tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Jamal, T. Co-Creating New Directions for Service Robots in Hospitality and Tourism. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe, J.L. Critical Pedagogy Primer; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, M.L.; Vossoughi, S. Perceiving learning anew: Social interaction, dignity, and educational rights. Harvard Educ. Rev. 2014, 84, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnie, P.; Azevedo, R. Metacognition. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Booker, A.; Goldman, S. Participatory design research as a practice for systemic repair: Doing hand-in-hand math research with families. Cogn. Instr. 2016, 34, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, S.; Zohar, A. Epistemic (meta) cognition: Ways of thinking about knowledge and knowing. In Handbook of Epistemic Cognition; Greene, J.A., Sandoval, W.A., Bratan, I., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Vossoughi, S.; Hooper, P.K.; Escudé, M. Making through the lens of culture and power: Toward transformative visions for educational equity. Harvard Educ. Rev. 2016, 86, 206–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.P.; Allen-Handy, A. The nature and power of conceptualizations of learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alise, M.A.; Teddlie, C. A continuation of the paradigm wars? Prevalence rates of methodological approaches across the social/behavioral sciences. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2010, 4, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincheloe, J.L. On to the next level: Continuing the conceptualization of the bricolage. Qual. Inq. 2005, 11, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H.A. On Critical Pedagogy; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Brennan, M.A. Conceptualizing community development in the twenty-first century. Commun. Dev. 2012, 43, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, J.; Duedahl, E.; Heape, C. Co-Designing Tourism for Sustainable Development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, R.G. The Curious Case of Affective Hospitality: Curiosity, Affect, and Pierre Klossowski’s. In Structures of Feeling: Affectivity and the Study of Culture; Sharma, D., Tygstrup, F., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 159–168.

- Haraway, D. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. In Turning Points in Qualitative Research: Tying Knots in a Handkerchief; AltaMira: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S.G. The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader: Intellectual and Political Controversies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Penuel, W.R. Infrastructuring as a practice of design-based research for supporting and studying equitable implementation and sustainability of innovations. J. Learn. Sci. 2018, 28, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassoughi, S. Embodied pathways and ethical trails: Studying learning in and through relational histories. J. Learn Sci. 2020, 29, 183–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jamal, T.; Kircher, J.; Donaldson, J.P. Re-Visiting Design Thinking for Learning and Practice: Critical Pedagogy, Conative Empathy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020964

Jamal T, Kircher J, Donaldson JP. Re-Visiting Design Thinking for Learning and Practice: Critical Pedagogy, Conative Empathy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020964

Chicago/Turabian StyleJamal, Tazim, Julie Kircher, and Jonan Phillip Donaldson. 2021. "Re-Visiting Design Thinking for Learning and Practice: Critical Pedagogy, Conative Empathy" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020964

APA StyleJamal, T., Kircher, J., & Donaldson, J. P. (2021). Re-Visiting Design Thinking for Learning and Practice: Critical Pedagogy, Conative Empathy. Sustainability, 13(2), 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020964