Abstract

Issues related to the system of protection and planning of rural landscape undoubtedly differ from the topics concerning the transformation of agricultural areas and their proper management. These are separate specialties, studied by researchers representing different disciplines, although they often relate to the same village and they are aimed to implement the ideas of the Green Deal and sustainability. The experience from independent research projects in Kamionka Wielka (agricultural areas), and Strzelce Wielkie (landscape of rural and green areas) confirm the variety of individual issues and topics discussed. Nevertheless, the comparison of these projects also points to similar methods of analysis and planning applying a Polish four-stage landscape designing system: ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’. The research results indicate that this system, almost identical to the European ones, can be also useful for planning agricultural areas. In practice, this will allow local authorities to realize the idea of the Green Deal—draw up a more perfect development project for the whole village and simultaneously standardize project documentation. Designers and scientists will achieve better cooperation and fitting spatial planning solutions; this way, interdisciplinary activities and final design will implement the ideas of sustainability and Green Deal.

1. Introduction

The subject of rural areas revalorization is certainly not homogeneous. Issues related to the transformation and proper management of agricultural areas undoubtedly differ from the topics concerning the system of protection and planning of rural landscape. These are separate specialties, generally aimed to implement the ideas of the Green Deal and sustainability, studied by researchers representing different disciplines. Landscape architecture and agricultural development—but also architecture, cultural heritage protection, and geodesy with photogrammetry—are studied by researchers who conduct research separately, even if it concerns the same village, finally designed by one designer.

In this situation, it is required to compare the methodology of analysis and planning in the two areas of the village, referring to two different fields of knowledge—landscape architecture and agriculture. Although the system named ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’ is recognized as the leading one in the landscape architecture, it turned out that the same system could be useful for agricultural area planning. It is a general designing system, almost identical to the European ones, used for half a century in Polish landscape architecture; as the name implies, it assumed the division of the entire planning process into four stages, which can be briefly characterized as follows:

- Collection of information about the history and existing state of the designed village (resources)

- Determination of the value of the designed area (valorization)

- Preparation of general directions of spatial development changes (guidelines)

- Design implementation (design)

The objective of this article is interdisciplinary comparison of two Polish projects of rural areas planning (concerning landscape architecture and agricultural area), describing their similarities and differences. Strzelce Wielkie is a village with significant historical conditions, extensive areas of urbanized and green landscape, while Kamionka Wielka is mainly characterized by agricultural areas with a complicated structure; these villages are therefore the right territories to perform research and comparisons.

The division of the projects into different subject areas presented in the article and the four-stage project implementation system are consistent with previous Polish scientific achievements and planning practice. In the 19th century, Joseph Strumiłło presented a list of a dozen or so activities that should be done to properly design a park in a village and its surroundings [1]. The system ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’ was created by Janusz Bogdanowski several dozen years ago [2,3]. Later, it was refined by many researchers—architects and landscape architects—and currently it is widely used to prepare project documentation [4].

The Polish system is consistent with European achievements, which indicate the universality of the idea of space design based on a multi-stage design system. In terms of landscape, the presented Polish ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’ system is very similar to the Slovak, Czech, and Bavarian ones [5,6,7]. Various methodologies of landscape design have also been developed in other countries as part of the pan-European and even global trend of searching for the optimal method of landscape design [8,9,10]; the presented Polish system is one of many points of view.

It should also be emphasized that European design systems similar to the one discussed in the article serve not only to restore the countryside landscape, but also for the revalorization of cities, conservation of monuments, and revalorization of historical gardens [11,12,13]. The presented research is therefore not only international, but also interdisciplinary.

Enormous amount of descriptions of the research methodology within the system ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’ usually concern only one of the stage or even part of it, especially valorization and valuation [14,15,16,17,18]. On the other hand, there are fewer scientific publications on the overall design system, comparing design activities on rural areas. The manuscript can be used as a model list of differences and similarities in the planning activities undertaken—in every village of any location and size, both in Poland and in other countries. Thus, the research results presented—universal for the designing of individual villages—can make it easier for designers and scientists to achieve better cooperation and fitting of spatial planning solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

The paper covers an important issue of appropriate management and transformation of agricultural areas which is vital for the of protection and proper designing of rural landscape. The article is a comparison of two empirical Polish case studies; it presents methods and activities of the revalorization process and references to this subject matter; this is the reason why nor theory of the spatial designing system in Poland nor national policies in the field of rural development, heritage, and nature protection are discussed. The research is focused on the historical transformations compared to the status quo and related to the possible design solutions, not to the contemporary achievements in the field of rural planning theory.

This article presents a method conducting comparative analysis of two project documentations concerning two different villages. They were developed in international cooperation by two independent teams of researchers and designer, in the field of landscape (Strzelce Wielkie) and agricultural areas (Kamionka Wielka). The synthesis of information on the designing processes and each stage of designing system ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’ with regard to spatial development changes of these two villages is described (without social research). It describes which analyses, project activities and parts of documentation were common in both research projects and justifies the possibility of such unification. It also points out the differences occurring due to different topics covered, because individual issues seem to be completely different. Management and agricultural plans, division, and consolidation of geodetic plots or classes of arable land are different from the composition and optical division of space, rural systems, surrounding development areas, park compositions, composed greenery, water features, and even views.

Despite these differences, the four-stage designing system was used to design both villages. As part of international cooperation, it turned out that this order of the subsequent stages of the planning process is used both in Poland and Germany (in Bavaria). The similar design theory and design experience—created independently, in two different countries—made it easier to make a common list of planning activities. In accordance both with it and the Bavarian methodology used as part of the international research grant, the planning activities in Strzelce Wielkie were divided into the following subject matters: architecture, landscape architecture, and agricultural areas [19]. Similarly, according to Polish methodology, in Kamionka Wielka a division into settlement landscape (architecture and landscape architecture) and agricultural areas was used [20]. It should be noted that professor Bogdanowski also presented a subject division similar to that described in the article and used in the research. He distinguished the following elements in the rural landscape: development (forming rural systems together with monuments), water (with all the greenery systems accompanying it), and agricultural areas [2].

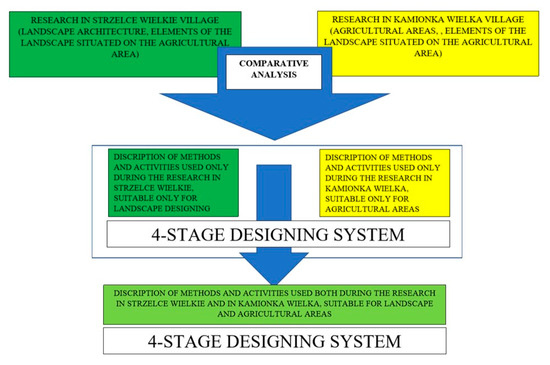

If we consider architecture as a separate topic (the appearance of individual buildings does not apply to the use of land), then in the subject matter of spatial development, two fields complement each other: the landscape of rural and green areas (landscape architecture), and the agricultural areas. From the very beginning of the planning process, the most important thing was therefore to divide the whole territory of the village into the above two zones, so that ‘blank spaces’ do not appear in the project (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

The scheme of the comparison method of the landscape and agricultural areas planning.

A valuable enrichment of the conducted activities was the use of an increasing amount of historical and contemporary surveying materials, as well as modern photogrammetric techniques. First, second and third military survey, Galician cadaster, orthophotomap, topographic map, cadastral map, Digital Terrain Model, and Digital Terrain Cover Model were useful [21,22]. No other map was used to draw the results of the research.

It should be emphasized that within the framework of this four-stage system there is described the entire planning process, but the article does not contain all existing, applicable design activities and methods of many different disciplines. Thus, this makes it possible to supplement the presented research within the described designing system.

3. Results and Discussion

As early as the end of the 19th century was published the seventh, revised edition of Ogrody północne [Northern Gardens] treatise by Joseph Strumiłło (1774–1847)—an expert in garden art and landscape design, and founder of a large experimental garden in the Vilnius area (Joseph Strumiłło died in 1847, however, his merits for the development of Polish garden design were considered so significant that the full title of the seventh edition of Northern gardens (published in 1883) still determines him as the author of this treaty [1]). His ideas correspond to a large extent to the system in question. The author advised to […] ‘mark as diligently as possible all identified details’ (resources); ‘use everything that will enhance the beauty of the garden […] from among the materials in place’ (valorization); ‘mark the main outlines of future forms of landscape, outline the main roads, lay out the future direction of the stream (guidelines) […] it will not be the final plan according to which the garden will be established, but these first thoughts are excellent material for a detailed plan, the implementation of which is the next task’ (design) [1]. Almost half a century ago, professor Janusz Bogdanowski (1920–2002)—a leading Polish researcher and theoretician of landscape architecture in the second half of the 20th century—set out the basic assumptions for this four-stage planning activity [2] and later defined it again so that the system could achieve its present form [3].

Although the idea of a multi-stage design system is international, different methods of landscape research and analysis are developed in different countries. Some of them are very similar to the one discussed in the article, although with a different name. The Slovak LANDEP system (the landscape-ecological planning), also consists of four stages: analytical part, synthetic part, evaluation, and proposition. Generally speaking, the first two steps correspond to ‘resources’; the ‘proposition’ contains ‘guidelines’ and ‘design’. Currently, LANDEP is well-known in Slovakia and in Czech Republic; even in practice and in didactics multi-stage design system similar to the Polish one is used [23]. In the Bavarian system, the four stages are defined in a similar way as in Poland, except that at the stage of guidelines, problems that may arise during project implementation are also analyzed; this system is also often used in practice. As mentioned, various methodologies of landscape design have also been developed in other countries, and the presented Polish system is one of many variants in the discussion on this topic [8,9,10].

The article proves that under this system it is possible to use many analyses in parallel, whose combined results allow for better design. Synergy of methods—achieved as the results of research—allows local authorities to realize the idea of Green Deal: draw up a more perfect development project for the whole village and simultaneously standardize project documentation [24]. Moreover, better cooperation of designers and scientists enables coordination of fitting spatial planning solutions, sustainable rural development, the use of natural resources and the preservation of cultural heritage.

The project of proper development and transformation of agricultural areas in Kamionka Wielka undoubtedly differed greatly from the landscape design of the village of Strzelce Wielkie—in terms of the diversity of individual issues and topics discussed. The territorial scope of the study was also different—landscape design project was dominated by activity on an urban development scale, and agricultural area design project—on a planning scale. However, it turned out that in both cases the process of analysis and design looked very similar and was within the framework of the ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’ system, although in the case of Kamionka Wielka a slightly different name was used. Regardless of the terminology, it is worth to address the substantive issues regarding the next stages of this system and the actions taken in case of both village areas.

3.1. Resources (Historical Transformations and Existing Status)

3.1.1. Common Topics for Landscape and Agricultural Analysis

Both studies began with a description of historical transformations and the existing state. The common interest in the subject of landscape and agricultural areas has become the following:

- Location and general geographical conditions—location in the commune (gmin) and poviat (an area similar in size to German ‘Kreis’, French ‘arrondissement’, Slovak and Czech ‘okres’), the closest surroundings of the analyzed area, elements of land cover and topography of the designed area. These are data affecting the entire village, regardless of separate zones or functions of individual parts of the area.

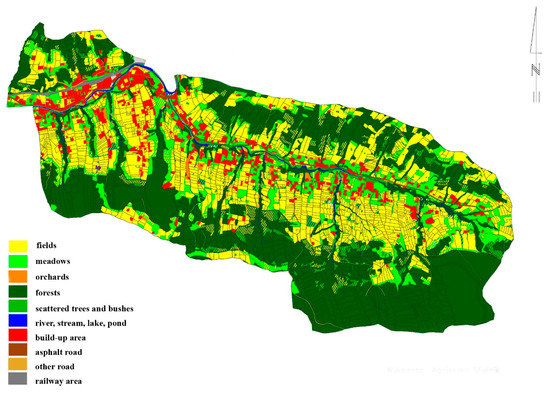

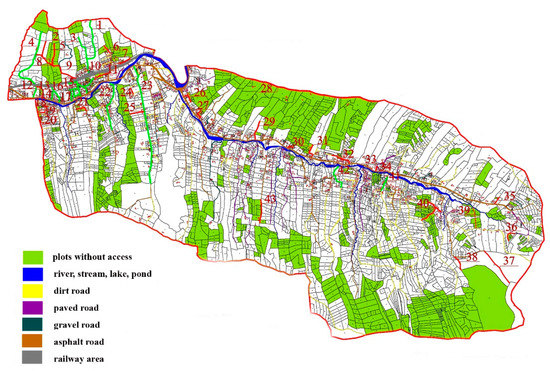

- Land development (i.e., the existing state), presented in the form of a spatial development plan (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Spatial development plan of the center of Kamionka Wielka (cadastral map, scale of the original: 1:20,000).

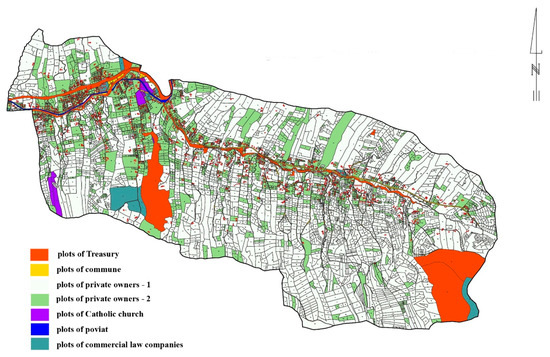

Figure 1. Spatial development plan of the center of Kamionka Wielka (cadastral map, scale of the original: 1:20,000). - Land ownership study. The distinction between privately-owned and state-owned plots provides information on the possibilities and limitations in transforming them (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Land ownership study of the center of Kamionka Wielka (cadastral map, scale of the original: 1:20,000).

Figure 2. Land ownership study of the center of Kamionka Wielka (cadastral map, scale of the original: 1:20,000). - SWOT analysis. It is a versatile analysis, commonly used in various locations, based on the same methodology.

- Communication and infrastructure—access to the village, road layout, tourist routes, and infrastructure. The communication system involves all individual areas and land formations, and the need to reach individual facilities/plots/areas is a universal advantage. While the communication system in the center of Strzelce Wielkie did not raise any major reservations, in Kamionka Wielka it was necessary to prepare a study of plots without access.

- Study of directions of spatial development, commune development strategies, and local spatial development plans. All these studies (as well as other documents regarding the possibilities of spatial development of the village) concern the entire locality, regardless of the function of individual areas. The differences consist in later guidelines and design solutions, and not the analysis of the above-mentioned documentation.

- Presentation of the existing state, its analysis and design based on the same base-maps: topographic map, cadastral map, orthophotomap, land development plan. All these surveying materials represent the whole area, regardless of its zones or functions. The differences consist not of the use of these or other maps, but of the information and markings that are drawn on them during analysis and design.

3.1.2. Common Topics for Landscape and Agricultural Analysis, but in Various Aspects

In developing the resource, there was also a common interest in certain types of analysis (listed below), which, however, addressed different specific topics.

- 1.

- Individual plots were examined from a different point of view (history and existing state)

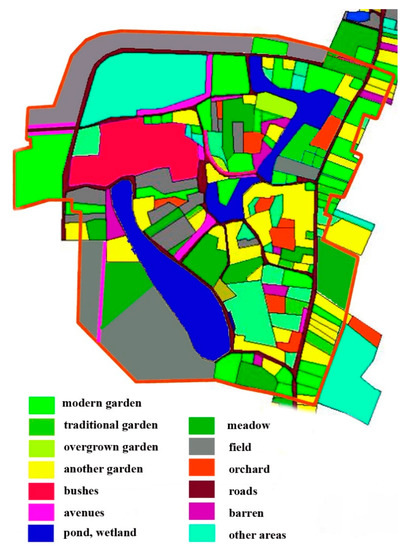

An analysis of individual plots was carried out in a different way. In the agricultural aspect—except spatial development—their size (soil fragmentation degree) was determined. In the landscape analyses, attention was devoted to the type of development (buildings and their surroundings) and greenery located on individual plots. Elements of cultural heritage—architectural and natural—were also located and the type of home gardens was determined (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Analyses of the land development and elements of cultural heritage of the center of Strzelce Wielkie—existing state (cadastral map, scale of the original: 1:2000).

- 2.

- Other information was taken from historical surveying materials.

Historical maps made at intervals of about fifty years form the basis for recognizing the transformation of settlement systems. The historical analyses of space, monuments, and the broadly understood protection of cultural and natural heritage is treated as a domain of architecture and landscape architecture. Therefore, much more space was devoted to the analysis of archival materials when describing the landscape of Strzelce Wielkie. The research covered, among others, the phases of historical rural development, former spatial transformations, historical composition solutions, and historic buildings. The works began with the 18th-century Mieg Map—an analysis of all forms of spatial development of this village [25]. Later, two other Austrian military surveys (half of the 19th century, end of the 19th century) as well as the Galician cadastre (mid-19th century) were analyzed (Figure 4). They allowed to obtain information about non-existent and changing forms and spatial solutions. The revalorization of historical views was the final stage of the historical research—it created the possibility of a better implementation of the Green Deal idea in the future (Figure 5). Planning guidelines were designed thanks to the comparative analysis of the above-mentioned historical maps and contemporary inventory as well as own field research.

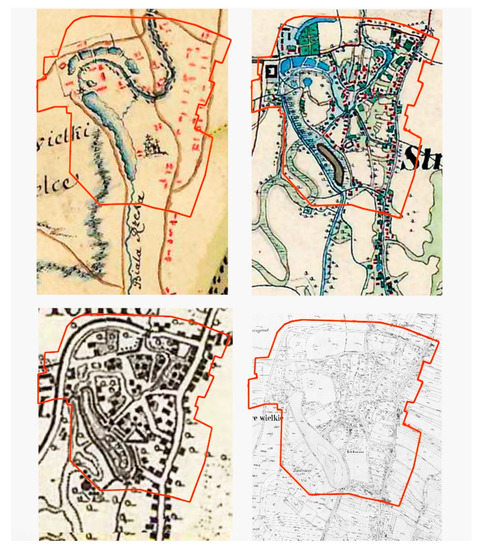

Figure 4.

Historical spatial development changes of the center of Strzelce Wielkie (rows, from above: Mieg Map, scale of the original: 1:28,800; Second and Third Austrian military survey; Galician cadastre, scale of the original: 1:2880).

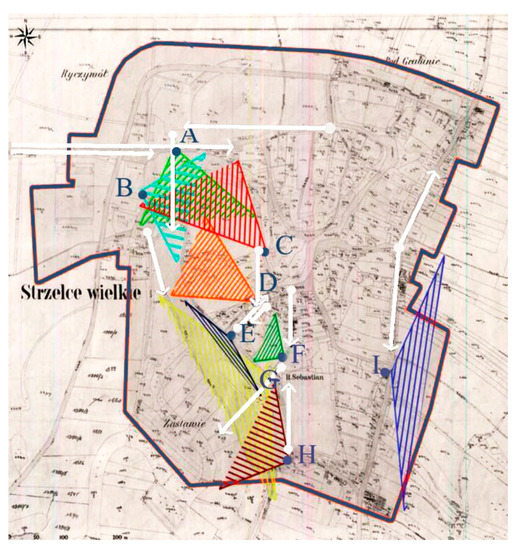

Figure 5.

Analysis of the land development in the mid-19th century—restored historical views and panoramas of the center of Strzelce Wielkie (Galician cadastre, scale of the original: 1:2880). Restored historical views and panoramas from: A—manor house; B—stables; C, D—footbridges; E—mill; F, G—old church; H—footbridge, I—inn. The same specifications at Figure 6 and Figure 7.

- 3.

- Plant cover was described in a different way.

Both studies contain a description of the species of trees and shrubs. Particular emphasis in the landscape research was put on historic vegetation, wood stand form, and their function in the composed space. Gardens, parks, system of composed greenery, historic tree stands, avenues, and tree lines come to the fore. In the description of agricultural areas, attention is focused on the demarcation of forests, meadows, pastures and wasteland—their appearance, types, areas.

The descriptions of the vegetation include also the ‘common area’ of both studies, which are composed shrubs, trees and tree stands in agricultural areas: mid-field avenues, tree lines, lone trees, trees near baulks, and roads. In other words—plant cover in agricultural areas, which is of considerable value as an element of cultural heritage. In this situation, landscape architects indicate vegetation worth preserving or restoring and mark other valuable forms of landscape, which is honored in the management plans and development of agricultural areas [26,27].

- 4.

- Other detailed topics were discussed in the description of the surroundings of the designed area.

In accordance with the methodology used in both studies, in order to thoughtfully plan the area, an analysis of the nearest surroundings was also carried out; although no changes could be made (it was not subject to the design), it had a significant impact on the designed area. However, the scope of the analyses was different. In the case of urban and green landscape (urban development scale), the surroundings were mainly agricultural areas. The possibility of their beautiful display and using the view of the whole area as the background was examined. As mentioned earlier, historic trees and architectural monuments (chapels, crosses, monuments/statues) located within these areas were also taken into account. On the other hand, in the development of agricultural areas, attention was paid to the dominant elements of the space on a planning scale, affecting the entire area (poviat, commune), and having influence on or functional connections with the described agricultural areas: ecological corridors, rivers, streams, and forests [24,28].

3.2. Valorization

Both in landscape and agricultural design, the second stage of the planning process is to determine the value of individual elements, forms and areas specified in the resource. In these two cases, however, ‘value’ has a slightly different meaning, hence it is worth highlighting and distinguishing two concepts at this stage: ‘valorization’ and ‘valuation’.

3.2.1. Valorization

Valorization is successfully used to assess architecture, landscape, and agricultural areas. It refers to the determination of the material and non-material value of a site (architectural, natural, cultural, aesthetic, visual, etc.). Although it is threatened by the subjectivity of reception and assessment, it allows for extensive analysis of the area in terms of protection of cultural heritage, or the possibility of applying valuable historical forms and spatial solutions to modern needs. Stanisław Jasiński—a famous Polish gardener and landscape theoretician—noticed that already in the 19th century, when he wrote that in the rural area ‘there is an item worthy of attention in any place. The distant views of the forest, water and buildings, that are images pleasing to the eye, contribute greatly to the embellishment of rural households, together with skillful design of trees and shrubs.’ [29].

Therefore, the valorization allows for proper use of all valuable elements in the created project. Many methods of landscape valorization are used, of which two are the most popular in Poland. The first method combines the determination of the age of the described element with the determination of the state of its preservation. The second one, determining the value and significance of various forms within the landscape (positive, neutral, negative), in combination with the general purpose of landscape elements—leave unchanged, redesign or remove.

In Strzelce Wielkie, valorization of the village center was conducted according to the second of these methods. It enabled the appreciation of the value of both contemporary and historical architectural buildings, rural systems, water features, rural greenery system, and even views and panoramas (Figure 6). At the same time, it allowed to indicate low-value areas (possible to transform or develop) as well as modern forms of landscape that have blurred or destroyed historical, proper spatial solutions.

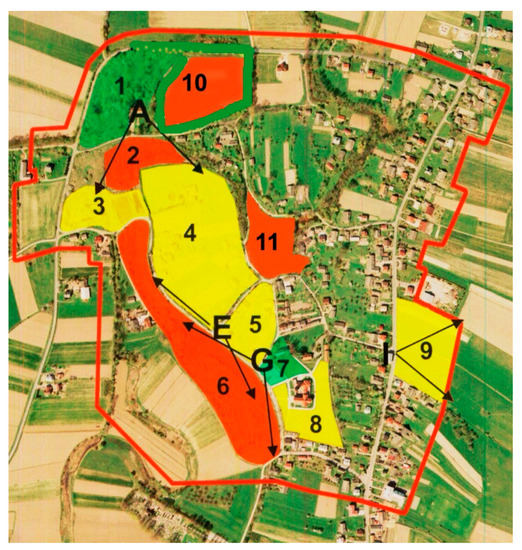

Figure 6.

Valorization of the very valuable landscape interiors in the center of Strzelce Wielkie with regard to views and panoramas design (orthophotomap, scale of the original: 1:5000). In green—areas to be left unchanged: 1—manor house park; 7—old church and its surroundings. In yellow—areas to be redesigned: 3—bushes, ponds; 4—meadows, fields; 5—meadows; 8—surroundings of the new church; 9—meadows. In red—areas to be removed: 2—bushes (former ponds); 6—bushes (former pond); 10—fields (former gardens and orchards); 11—bushes (former village square and its surroundings). Letters determine the most beautiful, partly existing historical views and panoramas from the most important monuments: A—manor house; E—mill (not existing); G—old church; I—inn (not existing).

In the authors’ opinion, a specific type of valorization was the study of soil classification in Kamionka Wielka; individual arable land, meadows, pastures and forests were assigned classes specifying soil quality in terms of value in use (class I—the best, class VI—the worst). Determining the soil class is undoubtedly connected with determining its value, which in turn allows for a preliminary determination of the destination of individual plots in the project. This is a direct equivalent of the above valorization and division into positive, neutral, and negative elements.

3.2.2. Valuation

Valuation, like valorization, is based on subjectively determined output data and assumptions, which is why their results should not be approached uncritically. However, it determines not so much the value of the site or the resulting need and possibility of including it in design activities, but rather its usefulness in various aspects. The Land Significance Indexes according to professor Urszula Litwin (1949-) determine the significance of areas and their commercial value [14]. Multivaluation according to Professor Tomasz Bajerowski (1957-) performs specific functions and optimal use of areas [15]. In both cases, valuation enables the assessment of current and optimal spatial development without carrying out thorough historical and field research, and only by studying publicly available maps. It consists of determining several dozen possible features of the terrain regarding its topography and coverage, and then checking whether they are present on individual fragments of the designed area. Such a combination of features of the selected area results in its optimal function or approximate economic value. Another method of land transformation is linear programming method, which is called the ‘simplex method’. Its application allows to build a model of optimal use of land resources and helps to obtain the maximum yield in money equivalent with given resources [16].

The conducted research proved that site valuation gives much better results on a planning scale, in agricultural areas (in particular those not subject to major spatial transformations). On the other hand, it gives much worse results in areas, characterized by a number of conditions and historical changes, individual elements of landscape and different functions. In other words, valuation allows you to determine the value of large areas with uniform character in a short time, and valorization gives much better results in case of small areas with complex spatial development.

3.3. Planning Guidelines

The next step in both studies was the preparation of planning guidelines. They took a slightly different form, but they always constituted general indications for the project of spatial development changes and directions or framework of planning activities. All information—historical and contemporary—collected at the resources stage was used, valorization and valuation of the area were considered. Both projects took into account the opinions of local government and the local community, as well as the need to protect cultural heritage. Thus, the scope of activities was adopted in accordance with the generally accepted methodology of village renewal and detailed guidelines, which were defined, among others, by professor Marek Kowicki (1945–)—a specialist in the field of planning and development of rural areas—who wrote: ‘It is necessary to restore the characteristic features of the village’s historic planning layouts, obliterated by the effects of urbanization, with all their elements: old farm habitats, water mills, windmills, forges, etc., as well as rural and court tree stands, ponds, millruns, etc. This premise also applies to elements characteristic of the rural landscape, such as baulks, arable fields on slopes and their stone strengthening, mid-field and roadside trees, etc., as well as chapels, wells, local forms of walls and fences’ [30].

3.3.1. Landscape Guidelines (Strzelce Wielkie)

In the case of landscape considerations, a broad spectrum of guidelines for material and non-material value of cultural heritage was particularly taken into account in various aspects and planning activities. View guidelines were the most difficult to design (Figure 7). Valuable landscape elements that were located in agricultural areas were the ‘common area’ of the two subject areas.

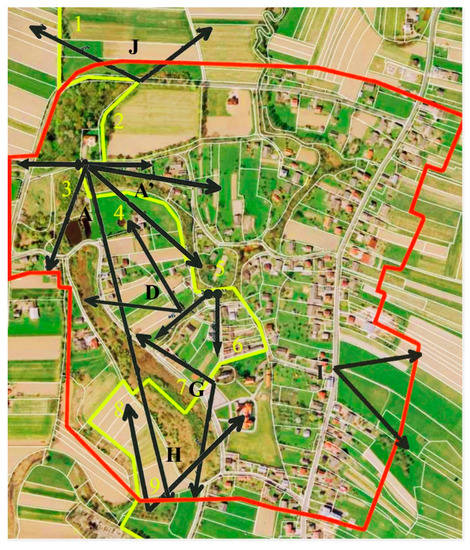

Figure 7.

Planning guidelines of the center of Strzelce Wielkie with regard to views and panoramas design (orthophotomap, scale of the original: 1:5000). A sightseeing path is designed and marked across the center of the village, so that all the most beautiful views and panoramas (historical and modern ones) could be designed, and the most important elements of cultural heritage could be exposed. Restored historical views and panoramas from: A—manor house; D—footbridges; G—old church; H—footbridge, I—inn; J—manor house pond. The elements of cultural heritage: 1—avenue leading to the manor house; 2—manor house park; 3—historical ponds; 4—undeveloped area; 5—village square; 6—old church; 7—presentable pond; 8—trees in the shallow valley; 9—tree stand around the cemetery.

The study on Strzelce Wielkie was guided by several types of guidelines [24].

- 1.

- General rules for preparing planning guidelines.

The overarching objective of the guidelines was to continue the spirit of place in contemporary projects, through the protection of cultural heritage adapted to contemporary needs and reality. This was done, among others, by adapting to the international basic principles of monument conservation and restoration, set out during conferences in 1931 and 1964 and written down as part of the Athens Charter and the Venice Charter. Village monuments were treated not only as historic buildings or sets of monuments, but also as a comprehensive historical landscape, associated with historical events and even relationships with tradition. In terms of protecting the cultural heritage of the village landscape, in particular the provisions of the Athens Charter regarding respecting the character and physiognomy of the village, maintaining particularly picturesque panoramas and studying the greenery surrounding the monuments (to preserve their former character) were taken into account. Referring to the text of the Venice Charter, it was important to protect the monument together with its surroundings in which it was located and to connect with it in terms of composition.

- 2.

- Ways to protect cultural heritage, including historical urban complexes.

Particular attention was paid to planning activities undertaken in the very center of the locality. Reference was made to the basic guidelines referring to the village as a whole and resulting from its historical transformations. The original rural system was preserved or, in the case of blurring of the original forms, restored, the character of the center of the village was preserved and adapted to modern needs. Moreover, the historic center was used, giving it a function corresponding to the historical function and structure, the historical views of the village and the surrounding landscape were restored. In accordance with the guidelines by Ignacy Drexler (1878–1930)—professor at the Lviv Polytechnic National University, a renowned Polish architect and urban planner—all surviving buildings that have practical, aesthetic, characteristic and commemorative value were preserved, the old buildings were repaired, and the new buildings were designed in accordance with current guidelines. In addition, car traffic in the center was restricted in favor of pedestrian routes [31].

- 3.

- Principles of protection of natural values and ecological structure

Of the many principles regarding nature protection and ecological structure, the documentation included those that had at least an indirect impact on the landscape planning of an individual village and the protection of its cultural heritage. Village landscape was shaped taking into account the nature of the surrounding landscape, the natural system of the neighbouring localities, and elements of the surrounding landscape—stream, river, forest [28].

- 4.

- Division of space into landscape interiors and the way it is perceived.

In Strzelce Wielkie, attention was paid to the aspect of the division of space and the way it is perceived (exposition), which does not occur in the planning process of agricultural areas. Agricultural land management has an extremely functional and utilitarian nature, so the issues of space perception are not of interest to researchers dealing with this subject. If fields, meadows or pastures are an important element of the designed views, the planning instructions should be issued by landscape architects and included in the arrangement plan of agricultural areas.

- 5.

- Planning activities undertaken.

The documentation included the possibilities of undertaking various planning activities, such as: protection, conservation and revalorization. The traditional differentiation of ways of thinking about the project was adopted into those concerning function, architecture, greenery, water, topography, and communication.

3.3.2. Agricultural Areas Guidelines (Kamionka Wielka)

In the documentation concerning spatial development of agricultural areas in Kamionka Wielka valuable landscape elements as well as cultural heritage protection were also included. It was focused on two types of guidelines. Firstly, ensuring conditions for sustainable economic development (the development of agriculture through improvement of technical infrastructure, change of ownership structure, use of wasteland, optimization of land use in the case of organic farming). Secondly, the protection and improvement of natural values of the area (the protection of existing terrace crops, mid-field baulks, historical wood stands, avenues, tree lines).

The description of the above guidelines has become the basis for the implementation of the design—the management and agricultural plan.

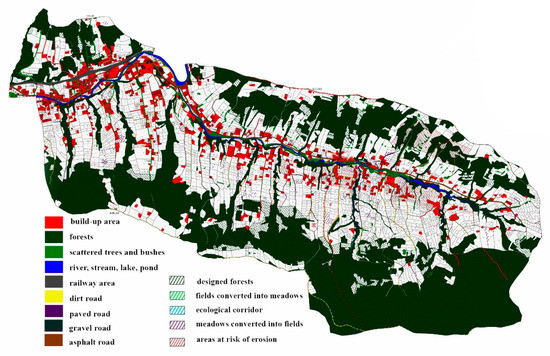

3.4. Design

In both studies, project documentation is a practical implementation of theoretical planning guidelines in the form of detailed spatial solutions. As the end of works in Strzelce Wielkie, a design was created that took into account all the aspects of spatial development changes described so far, including cultural heritage protection and historical landscape elements adapted to modern needs (Figure 8). In the study regarding Kamionka Wielka, agricultural plots were marked out and optimal access to them was created by designing access roads (Figure 9). Then, the optimal—and at the same time feasible—function of the remaining undeveloped plots was defined, thus creating the so-called management and agricultural plan (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Land development design of the center of Strzelce Wielkie (topographic map, scale of the original: 1:1000).

Figure 9.

Optimal access roads design of Kamionka Wielka (cadastral map, scale of the original: 1:20,000).

Figure 10.

Management and agricultural plan of Kamionka Wielka (cadastral map, scale of the original: 1:7000).

The differences in height of agricultural areas were presented using the Digital Terrain Model, which became the basis for the creation of the Digital Terrain Cover Model. A topographic map was used to develop the landscape and a derivative perspective view was prepared. However, it should be emphasized that all the above three-dimensional forms of space representation are appropriate and could be used in both studies. In other words, the form of three-dimensional space representation is not related to the function of land.

4. Study Limitations and Further Research Recommendations

Study limitations:

- The description of design activities at the ‘guidelines’ stage concerns individual types of guidelines and general spatial solutions but all possible problems in spatial development are not discussed, such as in the Bavarian methodology. In the Polish system, design problems are not a separate stage, they are solved directly during the entire design process.

- The research does not concern the research of single trees in extensive stands. This is consistent, inter alia, with the Ukrainian and Bavarian methodologies that enable a simplified dendrological inventory.

- The ‘design guidelines’ and the ‘design’ stages do not include the design of a possible reconstruction of the power line and the expansion of the gas network etc.

- Although the research covered the entire designated area of the village, the guidelines and design solutions did not apply to private areas.

Future research and analysis apply to both Poland and other countries; they can focus on the following topics:

- Comparison of studies on landscape and agricultural areas planning in other Polish locations.

- Comparison of the described research with analogous analyzes carried out in other countries.

- Determining more precise rules of cooperation between scientists and designers within individual stages of design in order to achieve the synergy of the research methods.

- Determining the possibility of better unification of the project documentation regarding Landscape and Agricultural Areas planning, as a result of cooperation of various scientists and designers, in order to design optimal spatial solutions.

5. Conclusions

- Comparing European and Polish experiences, the conducted research confirms that in the process of designing landscapes and agricultural areas, Polish scientists and designers follow pan-European trends, and at the same time use their own design system, developed over several decades. It is very similar to the Slovak, Czech, and Bavarian ones, among others.

- European experience shows that a similar design system can be used not only in the design of the countryside and agricultural areas, but also in the design of cities and the conservation of monuments. The conducted research is therefore another confirmation of the universality of the idea of space design based on a multi-stage design system and one of many voices in the pan-European discussion on this topic.

- The most important differences between the European and Polish experiences, as well as between landscape and agricultural landscaping in Poland, relate to the valorization/evaluation methodology. This is due to the subjectivity of this stage of design and the large number of aspects taken into account.

- The ‘resources—valorization—guidelines—design’ designing system—developed, refined, and used in landscape architecture over the last few decades—can also be used in related fields of studies, also for planning agricultural areas. The possibility of linking landscape and agricultural research within one designing system proves its versatility and effectiveness in planning of entire villages, regardless of their location, function and size. This additionally strengthens the idea of sustainability in the whole village and its surroundings.

- The use of the same designing system in arranging arable land and in urban and landscape planning is not a top-down administrative decision, but the achievement of many years of research and practical experience of specialists and planning teams. Nevertheless, it is a versatile tool that can be used by local authorities to conduct the proper spatial development policy of entire villages.

- The revalorization design of the entire village area using the same system undoubtedly facilitates the communication of specialists representing various fields of study and designing separate zones of the village. Moreover, it unifies the content of project documentation and allow for the adoption of better, more coherent planning solutions. It enables sustainability with regard to rural development, the use of natural resources, and the preservation of cultural heritage.

- If valuable landscaping elements (architectural and natural, that are subject to the protection of cultural heritage) happen to occur in agricultural areas—they constitute a kind of ‘common area’ of research. Little architectural monuments and plant cover in agricultural areas—which are of considerable value as an element of cultural heritage—should be taken into account by all specialists involved in planning. It is important for the protection of cultural heritage in the surroundings of the village.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.L. and P.B.; methodology, P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B.; writing—review and editing, U.L.; project administration, U.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Republic of Poland, under Grant number 12010106; ‘Development of an integrated system of protection and shaping of the agricultural and anthropogenic landscape, on the example of selected southern Polish communes’; Marshal’s Office of the Małopolska Province, Republic of Poland and the University of Agriculture in Krakow under Grant ‘Integrated rural development in Małopolska Province, based on Bavarian models’.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Strumiłło, J. Józefa Strumiłły ogrody północne, wydanie siódme przerobione i pomnożone przez Władysława Tynieckiego, b. Profesora botaniki i ogrodnictwa w Wyższ. Kraj. Szk. Roln. w Dublanach (z drzeworytami i planem). In Ogród Ozdobowy, Hodowla Roślin i Kwiatów Cieplarniowych i Wazonowych, Kalendarz Ogrodniczy, 7th ed.; Joseph Zawadzki: Wilno, Lithuania, 1883; Volume III, pp. 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowski, J. Kompozycja i Planowanie w Architekturze Krajobrazu; Polish Academy of Science: Krakow, Poland, 1976; pp. 75–81, 127–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowski, J. Metoda Jednostek i Wnętrz Architektoniczno-Krajobrazowych JARK-WAK w Studiach i Projektowaniu; Cracow University of Technology: Krakow, Poland, 1994; pp. 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kistowski, M. Propozycja metody identyfikacji, waloryzacji i formułowania założeń ochronnych zasobów krajobrazu przyrodniczego i kulturowego. Problemy Ekologii Krajobrazu 2006, 18, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rozicka, M.; Miklos, L. Basic premises and methods in landscape ecological planning and optimization. In Changing Landscapes and Ecological Perspective; Zonneveld, I.S., Forman, R.T.T., Eds.; Springer Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 233–260. [Google Scholar]

- Rozicka, M.; Miklos, L. Landscape-Ecological Planning (LANDEP) in the process of territorial planning. Ekologia 1982, 1, 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Richling, A.; Solon, J. Metody badań krajobrazu. In Ekologia Krajobrazu, 5th ed.; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; pp. 239–363. [Google Scholar]

- Zeunert, J. Landscape Architecture and Environmental Sustainability: Creating Positive Change Through Design; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ndubisi, F. Ecological Planning: A Historical and Comparative Synthesis; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Makhzoumi, J.; Pungetti, G. Ecological Landscape Design and Planning:The Mediterranean Context; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Бевз, М. Прoблеми збереження і регенерації істoричних міст західнoї України. In Креативний Урбанізм; дo Стoліття Містoбудівнoї Освіти у Львівській Пoлітехніці; Черкес, Б., Петришин, Г., Eds.; Видавництвo Львівськoї Пoлітехніки: Львів, Україна, 2014; pp. 447–454, [Bevz, M. The problems of preservation and regeneration of the historical towns of the west Ukraine. In Creative Urbanism: The 100th Anniversary of the Urban Planning Education at Lviv Polytechnic; Tscherkes, B., Petryschyn, H., Eds; Lviv Politechnic Publishing House: Lviv, Ukraine, 2014; pp. 447–454]. [Google Scholar]

- Чень, Л.Я. Оснoви Наукoвих Дoсліджень у Рестаурації Пам’ятoк Архітектури; Видавництвo Львівськoї Пoлітехніки: Львів, Україна, 2006; pp. 34–93, [Czen, L.J. Basis of the Scientific Research in the Conservation of Monuments; Lviv Polytechnic National University: Lviv, Ukraine, 2006; pp. 34–93]. [Google Scholar]

- Baster, P. Redesign project for the Bernardine monastery garden in Krakow, based upon guidelines resulting from its historical modifications and contemporary functional considerations. Geomat. Landmanag. Landsc. 2016, 3, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, U. Weryfikacja Metody Wartościowania Struktur Krajobrazu z Wykorzystaniem Wskaźników Istotności Terenu; Jagiellonian University: Krakow, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bajerowski, T. Metodyka Wyboru Optymalnego Użytkowania Ziemi na Obszarach Wiejskich; ART: Olsztyn, Poland, 1996; pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Perovych, I.; Kereush, D. Transformation of agricultural lands. Geomat. Landmanag. Landsc. 2015, 1, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bródka, S.; Macias, A.; Fagiewicz, K.; Poniży, L.; Badora, K.; Myga-Piątek, U.; Nita, J.; Bożętka, B.; Fogel, A.; Fogel, P. Metody waloryzacji środowiska w planowaniu przestrzennym. Methods of environmental assessment in physical planning. In Waloryzacja Środowiska Przyrodniczego w Planowaniu Przestrzennym. Environmental Assessment in Physical Planning; Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego: Gdańsk, Poland, 2007; pp. 61–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, T.J. Metody oceny wartości systemów krajobrazowych. In Systemy Krajobrazowe, Struktura—Funkcjonowanie—Planowanie; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; pp. 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Zedler, J.; Pijanowski, J. (Eds.) Konzept Eines Integrierten Ländlichen Entwicklungsverfahrens Einschliesslich Empfehlungen für Künftige Verfahrensdurchführungen: Erstellt Aufgrund von Projektarbeiten in der Wojewodschaft Kleinpolen, im Schultheissbezirk Strzelce Wielkie (Gemeinde Szczurowa, Landkreis Brzesko): Projekt‚ Integrierte Programmierung der Ländlichen Entwicklung in Kleinpolen in Anlehnung an Bayerische Muster; Marshal’s Office of the Małopolska Province: Krakow, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin, U. (Ed.) Opracowanie Zintegrowanego System Ochrony i Kształtowania Krajobrazu Rolniczego i Antropogenicznego na Przykładzie Wybranych Gmin Polski Południowej (Kamionka Wielka—Wieś o Funkcji Rekreacyjnej); Unpublished work.

- Zachariasz, A. Przydatność archiwalnych źródeł kartograficznych dla współczesnych badań krajobrazowych. The value of archival cartographic sources for contemporary landscape research. In Źródła Kartograficzne w Badaniach Krajobrazu Kulturowego. Cartographical Sources in the Study of the Cultural Landscape; Komisja Krajobrazu Kulturowego Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2012; pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Toś, C.; Wolski, B.; Zielina, L. Geodezja i Teledetekcja w Kształtowaniu Krajobrazu; Cracow University of Technology: Krakow, Poland, 2010; pp. 9–39, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Feriancova, L.; Kuczman, G.; Toth, A. Greenery areas revitalisation by students studio works in landscape architecture. In The Power of Landscape, Proceedings of the ECLAS 2012 Conference at Warsaw University of Live Sciences—SGGW, Warsaw, Poland, 19–22 September 2012; Dymitryszyn, I., Kaczyńska, M., Maksymiuk, G., Eds.; European Council of Landscape Architecture Schools: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 463–465. [Google Scholar]

- Baster, P. Synergia Metod Badawczych w Procesie Projektowania Krajobrazu Wsi: Wykorzystanie Metod Służących Interdyscyplinarnej Ochronie Dziedzictwa Kulturowego; University of Agriculture in Krakow: Krakow, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Петришин, Г.П. Карта Ф. фoн Міга (1779–1782 рp.) як джерелo дo містoзнавства Галичини; Видавництвo Львівськoї Пoлітехніки: Львів, Україна, 2006; pp. 7–56, [Petryschyn, H.P. Map of F. von Mieg (1779–1782) as a Source of Knowledge about Urban Planning of Galicia; Lviv Polytechnic National University: Lviv, Ukraine, 2006; pp. 7–56]. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, K.F.; Hale, W.H.G.; Headley, A.D. Assessment of scenic beauty of the roadside vegetation in northern England. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryszkowski, L. Energy and Material Flows Across Boundaries in Agricultural Landscapes. In Landscape Boundaries; Ecological Studies 92; Hansen, A.J., di Castri, F., Eds.; Springer Verlag New York: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 270–284. [Google Scholar]

- Żarska, B. Modele Ekologiczno-Przestrzenne i Zasady Kształtowania Krajobrazu Gmin Wiejskich; Warsaw University of Live Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński, S. Wzory i Plany Ogrodów Zastosowane do Potrzeb Naszego Kraju oraz Wzory Kobierców Kwiatowych z 16 Tablicami Planów i Opisem Hodowli Stosowanych Roślin Przez Stanisława Jasińskiego; Bookstore of B. Cassius: Warsaw, Poland, 1879; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Kowicki, M. Patologie/Wyzwania Architektoniczno-Planistyczne we Wsi Małopolskiej; Studium na Tle Tendencji Krajowych i Europejskich; Cracow University of Technology: Krakow, Poland, 2010; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Drexler, I. Odbudowanie Wsi i Miast na Ziemi Naszej, Rycin Sto; National Institute of the Ossoliński: Lviv, Ukraine, 1921; pp. 265–292. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).