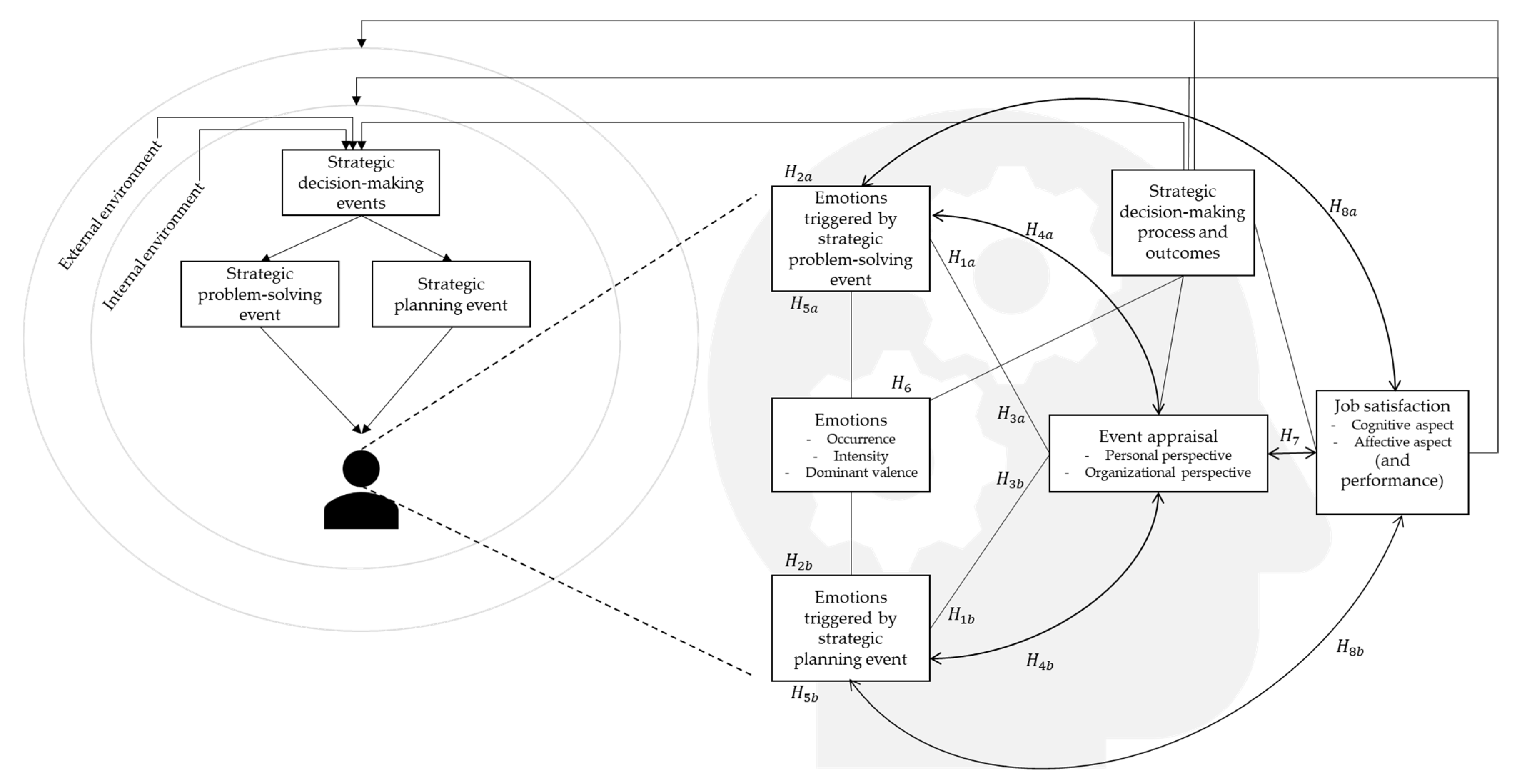

The results section is divided into results related to strategic problem-solving, strategic planning, and job satisfaction.

4.1. Solving a Strategic Problem

While there are differences in the event appraisal (n = 3 for negative, n = 1 for neutral and n = 4 for positive; there were 10 differences in appraisals of events when observing individual cases), it can be noticed that the majority of respondents (82.14%) appraised the events the same way from both perspectives (

Table 1). This seems to confirm that an event can be appraised from different perspectives and indicates that some HR managers may perceive the same event differently from the perspective of the organization and from a personal perspective, which is in line with [

17]. However, the observed differences are not large enough to appear as statistically significant (Wilcoxon signed ranks test shows that with

p > 0.05 the null hypothesis cannot be rejected), thus we must conclude that for the event of strategic problem-solving

cannot be rejected. That is not in line with presumption about the differences in event appraisal from the personal and organizational perspective—at least not for the strategic problem-solving event at 5% statistical significance level. Nevertheless, we are not ready to fully abandon that presumption. First, the data show that roughly one-fifth of the respondents does make the distinction. While this is not enough for achieving statistical significance, it still shows that respondents can differently appraise the events from personal and organizational perspective. Second, while the respondents can appraise the event from different perspectives it does not mean that they have to appraise it differently, as contextual characteristics of the event may support the same appraisal of the event from personal and organizational perspective.

The descriptive statistics points to average moderate experience of emotions’ intensity related to the event of solving a strategic problem, with the exception of envy, shame, jealousy and hate that are very low on average. The variation of expressed emotions is rather high for most of the expressed emotions, which shows variability between individuals.

The respondents experienced from 3 to 17 emotions related to the event, with an average occurrence of 9 emotions. The emotion with the highest number of occurrences is hope, followed by pride, enthusiasm, and happiness (

Table 1). The lowest number of occurrences refers to hate, envy, and jealousy. While emotions vary given their occurrence and intensity, it can be noticed that most respondents experienced a variety of emotions related to an event of strategic problem-solving, which confirms

.

Given the variability, it makes sense to look deeper into the data and examine the descriptives regarding the appraisal of the events. The respondents classified the events from the personal perspective and from the perspective of the organization.

Given the variability, it makes sense to look deeper into the data and examine the descriptives regarding the appraisal of the events, in line with the research objective to determine which emotions occur and in what intensity during the event. The respondents classified the events from the personal perspective and from the perspective of the organization.

When observing the emotion intensity after data separation by event appraisal, it can be noticed that, on average, frustration and disappointment are the most prominent emotions and occur with high average intensity for negative events (

Table 1). This finding is not in line with the previous research that linked happiness to problem-solving [

51]. For respondents who appraised the event as positive, the emotion with the highest average intensity is enthusiasm, followed by pride, hope, joy, and happiness. In case of a neutrally appraised event, frustration and hope appear with higher intensity for both appraisal perspectives. In case of negatively appraised events, frustration is the most pronounced, followed by disappointment, sadness, and anger.

While the emotions of dominantly positive valence occur with regard to positive events and those of dominantly negative valence with regard to negative events, it is interesting to notice that hope is, on average, at least moderately expressed as experienced emotion regardless of the event appraisal, as well as the most frequently reported emotion (so it seems that the saying “there’s always hope” is true for HR managers).

It can also be noticed that a neutrally appraised event reveals emotions with lower average intensities in comparison to negatively and positively appraised events, both from a personal and organizational perspective. Given the affective events theory, and this data, it can be assumed that the event valence is not just the trigger for the emotion occurrence, but also for the intensity of the related emotions.

To examine if there is a difference in intensity of experienced emotions given the event appraisal from different perspectives (

), a non-parametric hypothesis testing was conducted and the results show statistically significant differences in the intensity of the most experienced emotions, if observed at 10% statistical significance. There is no statistically significant difference in the amount of envy, shame, hope, love, and surprise regarding the event appraisal from a personal perspective (

Table 2). The same is true for the event appraisal from the organizational perspective.

If we observe only statistical differences at 1% level (

Table 2), the results reveal differences in anger, disgust, happiness, sadness, contempt, frustration, and disappointment regarding the event appraisal from a personal perspective; and disgust, sadness, contempt, frustration, and disappointment regarding the event appraisal from a personal perspective. This shows that mostly dominantly negative valence emotions vary depending on a particular event appraisal for the observed HR managers. The results point out to rejection of the

for the statistically significant emotions, meaning that there are differences in intensities of experienced emotions given the event appraisal from personal and organizational perspective.

Moreover, the revealed differences (at 1% level) do not match for the two event appraisals and reveal statistically significant differences in two emotions more for the event appraisal from a personal perspective (anger and contempt). The above confirms that HR managers can differentiate the event from a personal and organizational perspective and that for some of them, the evaluation of the event will be different from a personal and organizational perspective, and that emotions play a role in these distinctions—which supports the presumption related to the first hypothesis. In order to understand the source of variation, it is important to mention that all the differences in the respondents’ event appraisal reveal more positive classification of the event from the perspective of organization, which also limits the interpretation. The intensity of experienced anger and contempt may be an indication of the difference in HR managers’ appraisal of the event from the organizational and personal perspective, when the event is assessed as worse from the personal perspective than from organizational.

The provided analysis indicates that some emotions co-occur given the event, which requires additional analysis. Then, it is examined whether the occurrence of emotions correlates to the event appraisal.

The correlation between the event appraisal and emotions is assessed using the non-parametric Kendall Tau-b correlation coefficient, with applied stratified bootstrap based on event appraisal (to compensate for the small sample). Bootstrap results are based on 1000 stratified samples and reveal relatively small biases and standard errors and do not lead to an increase in data variability.

The analysis reveals weak to moderate statistically significant correlations (

Table 3). There are positive correlations of enthusiasm, happiness, joy, and pride to event appraisal from a personal perspective; meaning that they occur in the higher intensity for positively assessed event and with lower intensity for the negatively assessed events, as expected. The negative correlations to event appraisal from a personal perspective are anger, contempt, fear, frustration, disappointment, shame, disgust, hate and sadness; meaning that they occur with higher intensity for negative events and with lower intensity for the positive ones. Results point out to rejection of

for stated statistically significant emotions, which means that there are statistically significant correlations and that dominantly positive emotions positively correlate and dominantly negative emotions negatively correlate to event appraisal.

It can be noticed that contempt, fear, shame, and hate do not occur as statistically significant correlations with the event appraisal from the perspective of the organization. These differences in the statistically significant correlations between event appraisal from a personal and organizational perspective show that some emotions of dominantly negative valence play a role in the personal experience of the event, regardless of its meaning for the organization. This additionally confirms the results from the hypothesis testing, meaning that some events may be positive or neutral from the perspective of the company, but the role of the HR manager position puts the respondents in a situation which they perceive worse from their own perspective, which causes experience of different intensity of contempt, fear, shame, and hate.

The intensities of emotions correlate to the event appraisal, meaning that if we want to additionally explore the coexistence of emotions, the correlation analysis must be conducted such that it uses the event appraisal as a control variable.

Thus, partial correlation examination should reveal the relationships between the intensities of experienced emotions for observed HR managers ().

As it might have been expected, there are statistically significant and moderate positive correlations between the emotions of dominantly positive valence (E1–E6), regardless of the event appraisal (

Table 4). The more intensely one of those emotions is experienced, it is likely that others will also be intensely experienced. The exception is strong positive correlation between happiness and joy, meaning that if happiness is intensely experienced, joy will be intensely experienced as well. The observed correlations between the emotions of the dominantly negative valence do not so consistently occur as those of the dominantly positive valence, but show some statistically significant correlations, which are positive regarding the direction and weak to moderate regarding the intensity.

Revealed correlations show that there is a relationship between the intensities of emotions, separately for group E1–E7 and group E8–E18, with stated exceptions. This reveals the coexistence of different emotions, regardless of the event appraisal, and leads to the rejection of .

The most interesting observation occurs for the emotions that positively correlate to emotions both dominantly positive and negative in valence. There are statistically significant weak to moderate positive correlations between the intensities of experienced hope and fear, joy and fear, love and envy, love and jealousy, surprise and fear, surprise and disappointment, surprise and shame, surprise and disgust, and surprise and jealousy. Four emotions with dominantly positive valence positively correlate to emotions of dominantly negative valence, allowing not just for their coexistence but also for a relation in their intensities, which confirms and the presumption of emotions coexistence.

Additional indication of the simultaneous existence of emotions for HR managers when solving a strategic problem is the lack of the statistically significant negative correlations between the emotions in group E1–E7 and group E8–E18. If negative correlation occurred, that would mean that as intensity of emotions E1–E7 rises, the intensity of emotions E8–E18 would diminish. Along with revealed positive correlations between emotions of different dominant valence, this finding allows the coexistence of the emotions of different dominant valence without the existence of linear relationship between them. The exceptions are weak and negative statistically significant correlation between the intensity of experienced enthusiasm and hate, pride and shame, and hope and hate; meaning that, for example, for higher intensity of experienced hope there will be lower intensity of experienced hate (and vice versa).

Along with the revealed positive correlations, the lack of negative correlations between most of the emotions from the two groups means that the existence of emotions from one group does not mean the absence of the emotions from the second group and confirms the previous findings by [

2,

3,

17].

Positive correlations between emotions in group E1–E7 and the same kind of correlation between the emotions in group E8–E18, but without the negative correlations between all of (or most of) the emotions of different groups, reveal the coexistence of the various emotions and indicates emotional turmoil of the HR managers when solving a strategic problem.

4.2. Strategic Planning

In the event of strategic planning appraisal from personal and organizational perspective fewer differences in appraisal of strategic planning event occur (2 for negative and 2 for positive event appraisal), with 5 differences when observing individual responses. Stated differences were not enough to appear as statistically significant (Wilcoxon signed ranks test shows that with p > 0.05 the null hypothesis () cannot be rejected). The fact that 10.42% of respondents show the ability to differently appraise the events, shows that the presumption of different cognitive appraisal of the events should not be ignored. However, the hypotheses testing also shows that the different cognitive appraisal of strategic decision-making events (both strategic planning and problem-solving) is not common occurrence—it is rare. In the most cases of different appraisal for both events, the events are appraised as worse from personal perspective, which may be an indication of mismatching or disagreement in personal experience (including opinions and attitudes) to the organizational.

The highest number of occurrences refers to enthusiasm, hope, and happiness. Individually (per respondent), the number of occurred emotions varied from 2 to 18, with an average of 8 experienced emotions (7.81). The most intensely experienced emotions are enthusiasm, pride, happiness, hope, and joy, which occur with such intensity only for positive events. The emotions which prevail for the negative event of strategic planning are frustration, disappointment, sadness and hope. The events of strategic planning appraised as neutral, do not provoke high intensity emotions (except for sadness when appraised from the perspective of the organization), as averages point to weak emotion intensities. The data presented in

Table 5 confirms that the event of strategic planning is a trigger of both positive and negative emotions (

).

The number of emotion occurrences is lower for the strategic planning event than for problem-solving. In comparison to problem-solving (

Table 1), in strategic planning the respondents show smaller average number of experienced emotions with higher variability (

Table 5). This observation is confirmed by related samples Wilcoxon signed rank test, used for the repeated measures on the same subject under different conditions (in this case, different events of strategic decision-making). There are statistically significant differences (

p < 0.05) in the intensities of hate, contempt, fear, frustration, disappointment, disgust, hope, surprise and sadness given the type of strategic decision-making event. For each case in the observed differences, the average intensity of experienced emotion is higher for the event of strategic problem-solving. Average intensities of experienced enthusiasm and happiness are higher for the event of strategic planning (while average intensities for other emotions are higher for strategic problem-solving event), but those differences are not statistically significant. That means that

can be rejected for the stated emotions, which is in line with the presumption that the two strategic decision-making events will trigger different levels of emotions. Thus, we may conclude that the event of strategic problem-solving provokes the higher intensities of hate, contempt, fear, frustration, disappointment, disgust, sadness, surprise, and hope than the event of strategic planning.

While differences in the emotions expressed in the event of strategic planning seem to be evident from the descriptives, hypothesis testing is due for confirmation ().

Similarly, as for the event of solving a strategic problem, non-parametric tests show that there are statistically significant differences between emotion intensities given the event appraisal, both from the perspective of the organization and from a personal perspective (

is rejected). If we observe only the differences that arise at 1% statistical significance, for event appraisal from the perspective of the organization they occur for: enthusiasm, disappointment, disgust, happiness, joy, pride, and sadness; while for event appraisal from a personal perspective they occur for: anger, enthusiasm, disappointment, shame, disgust, happiness, joy, pride, and sadness (

Table 6).

The distinction appears for anger and shame. While the distinction in anger can be related to solving a strategic problem, shame differs given the differences in two event appraisals. At this point, we can assume that the intensity of anger is the best indicator of the difference between event appraisals from a personal and organizational perspective.

This makes sense, as the anger is triggered by circumstances and external (someone else’s) action, which can arise from event characteristics: level of involvement and perception of control.

Enthusiasm, happiness, hope, joy, and pride positively correlate to event assessment from a personal perspective, while anger, contempt, frustration, disappointment, shame, disgust, and sadness negatively correlate to event assessment (

Table 7,

is rejected). From the perspective of the organization, enthusiasm, happiness, joy, and pride positively correlate with the event appraisal, while anger, frustration, disappointment, shame, disgust and sadness correlate negatively. Higher intensities of dominantly positive emotions lead to positive event appraisal, while higher intensities of dominantly negative emotions lead to negative event appraisal. Contempt and hope appear statistically significant only for the event appraisal from a personal perspective, pointing out that the difference in intensity of those emotions may relate also to the difference in the event appraisal from different perspectives.

When observing partial correlations of emotions that occur for the event of strategic planning (

Table 8), some similarities to the partial correlation analysis of emotion intensity for the event of solving a strategic problem may be noticed—emotions in the first group (E1–E7) mostly corelate positively amongst themselves, as well as emotions in the second group (E8–E18).

However, there are also some differences. First, the observed correlations between emotions in both groups reveal a few positive and strong correlations. Second, there are fewer positively correlated emotions of positive valence with emotions of negative valence. The exceptions are surprise and love, which confirms

and the coexistence of emotions of different dominant valence (namely,

is rejected). The intensity of experienced surprise positively correlates with fear, frustration, disappointment, hate, jealousy, and sadness (while there are no statistically significant correlations to emotions E1–E7)—and that may indicate that respondents experience surprise as a dominantly negative valence emotion and not as emotion of positive valence [

20,

55]. Third, several negative correlations occur between emotions from the first and second.

Fewer positive correlations between emotions of dominantly positive with emotions of dominantly negative valence leads to conclusion that the separation between the emotions of dominantly positive and negative valence is much clearer for the event of strategic planning than for event of solving a strategic problem. In addition, there are more negative correlations between the intensities of emotions from the two groups. Nevertheless, the findings still allow the coexistence of dominantly positive and negative valence without the relationship between their intensities. Observed in combination, findings lead to conclusion that the event of strategic planning is less emotionally ambivalent for examined HR managers than the event of solving a strategic problem, regardless of the event appraisal.

4.3. Job Satisfaction

Affective events theory suggests that work-related events influence employees’ job satisfaction. While the theory primarily focuses on the aggregation of hassles and uplifts that ultimately lead to a certain level of satisfaction, here we examine the relationship of only two separate events to job satisfaction. The above represents a limitation of possible interpretation, but it is worth examining the relationship given that the events’ importance, consequences, and experienced emotions may relate to overall job satisfaction.

Table 9 shows that strategic problem-solving event moderately and positively correlates to job satisfaction (both from a cognitive and affective perspective) at 1% level of statistical significance. Statistically significant correlation does not occur for the event of strategic planning. The hypotheses

and

should be rejected, as results show that only the appraisal of strategic problem-solving correlates to job satisfaction. The lack of the statistically significant correlation between appraisals of strategic planning events to job satisfaction does not allow rejection of

and

. That means that

is only partially proven and is valid for the event of strategic problem-solving. This points out that the events of strategic problem-solving are a better indicator of overall job satisfaction than the events of strategic planning. Given the moderate correlation, it must not be overlooked that there are other factors that shape job satisfaction but are not accounted for in this analysis.

It can also be noticed that the correlation coefficients are higher for the relationship between job satisfaction and problem-solving event appraisal from a personal perspective, as well as the correlation coefficients between job satisfaction from affective perspective and both strategic problem-solving appraisals. This leads to conclude that the event appraisal from a personal perspective, as well as the emotional aspect lead to stronger (however, still moderate) relationship between the event appraisal and job satisfaction. Given this finding, it makes sense to examine the relationship between the emotions experienced during events and job satisfaction. In order to do so, but to account for the event appraisal, the data were separated given the event appraisals for both strategic events. Due to the size of the subgroups, the correlation analysis could have been conducted only for the subgroup where the event of problem-solving was appraised either negatively or positively from both personal and organizational perspective; and only for positively appraised event of strategic planning from both personal and organizational perspective.

Given the revealed statistically significant correlation coefficients (

Table 10), it can be noticed that different emotions appear significant in the relationship between job satisfaction to different events and different event appraisal (

). Negatively experienced event of strategic problem-solving reveals moderate to strong relationship of contempt, enthusiasm, fear, hope and joy to cognitive aspect of job satisfaction; and moderate relationship of enthusiasm, fear, shame, disgust, hope, and sadness to affective aspect of job satisfaction. In case of negatively appraised event of problem-solving, for both cognitive and affective aspect of job satisfaction, enthusiasm, fear, hope, and joy play a role. The respondents who participated in a negatively perceived event of strategic problem-solving will probably show higher level of job satisfaction if they experienced enthusiasm, fear, hope, and joy at higher intensity, and contempt (for cognitive aspect) and disgust (for affective aspect) at lower intensity.

For a positively appraised event of strategic problem-solving, there is a weak and positive relationship between enthusiasm and cognitive aspect of job satisfaction (meaning that higher intensity of experienced enthusiasm relates to higher job satisfaction); and moderate and negative relationship between disappointment and affective aspect of job satisfaction (meaning that higher intensity of experienced disappointment relates to lower job satisfaction). With both cognitive and affective aspect of job satisfaction, sadness correlates negatively with moderate intensity, meaning that the job satisfaction will probably be lower if sadness is experienced at higher intensity.

For a positively appraised event of strategic planning, frustration and disappointment show moderate and negative relationship to cognitive and affective aspect of job satisfaction, meaning that experienced intensities of frustration and disappointment diminish job satisfaction.

Thus, both and can be rejected, confirming . It seems that the respondents who experienced the strategic event negatively, experience more distinct emotions which correlate to job satisfaction.