Sustainability-Conscious Stakeholders and CSR: Evidence from IJVs of Ghana

Abstract

1. Introduction

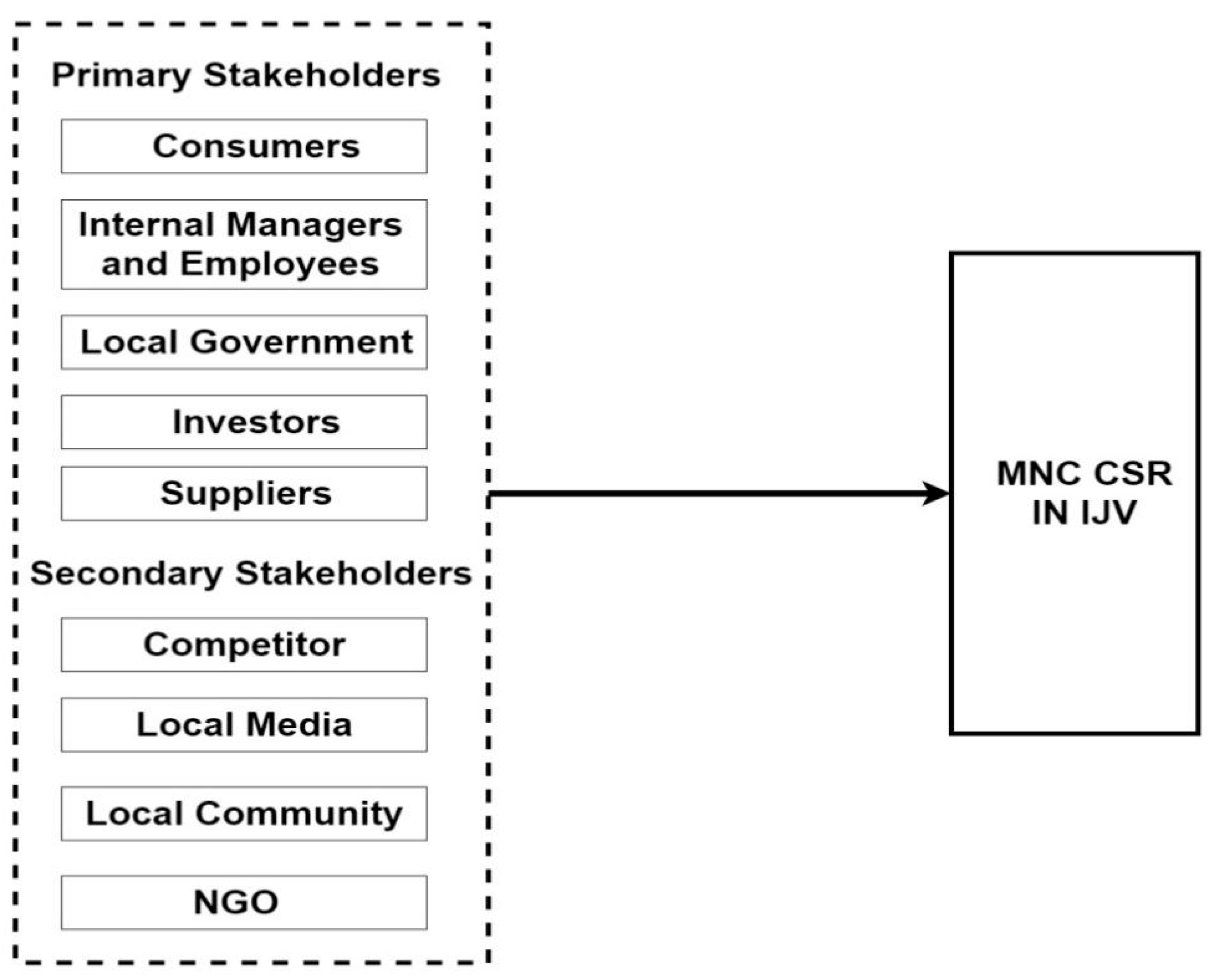

2. Theoretical Background

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Primary Stakeholders

3.1.1. Consumers

3.1.2. IJV Managers and Employees

3.1.3. Government

3.1.4. Suppliers

3.1.5. Investors

3.2. Secondary Stakeholders

3.2.1. Competitors

3.2.2. Media

3.2.3. Local Community

3.2.4. Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

3.3. Structure of Ownership

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data Sample and Collection

4.2. Variable Measurement

5. Results

5.1. Results of the First Stage of Analysis

5.2. Results of the Second Stage of Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Measurement (Ranging from 1 = Very Strongly Disagree to 5 = Very Strongly Agree) | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Consumers (Adapted from Tian, Wang, and Yang [82]) | (I) Consumers care about environmental protection in the daily consumption. (II) Consumers pay attention to some social issues involving firm’s charitable donations. (III) Consumers tend to buy those products which are produced by firms that are socially responsible rather than goods which are fine and inexpensive. | 0.879 |

| IJV managers and employees (Adapted from Munilla and Miles [83]) | (I) Our managers and employees perceive CSR as an important mechanism potentially contributing to the creation of corporate value. (II) Our managers and employees perceive that CSR enhances competitive advantage, and eventually improves the economic value of the firm. (III) Our managers and employees believe firms need to contribute to local countries, societies, and markets. (IV) Our managers and employees believe being ethical and socially responsible is the most important thing a firm should do. | 0.824 |

| Governments (Adapted from Qu [84]) | (I) The local government has stricter regulations to protect the consumers. (II) The local government has effective regulations to encourage firms to improve their product and services quality. (III) There are complete laws and regulations to ensure fair competition. | 0.933 |

| Suppliers (Adopted from Park and Cave [4]) | (I) Local suppliers tend to prefer close cooperation with firms which are socially responsible. (II) Local suppliers tend to prefer the maintenance of cooperation with firms which are socially responsible. (III) Local suppliers have a propensity to apply social and environmental requirements to their business relationships. | 0.98I |

| Investors (Adopted from Park et al. [59]) | (I) Investors tend to prefer investment into firms which are socially responsible. (II) Investors expect firms to implement various and active CSR practices in host country. (III) Investors actively indicate and support firms’ CSR practices. | 0.985 |

| Competitors (Adapted from Lindgreen et al. [33]) | Due to local business environment, firms suffer from pressure on emulating competitors’ (I) social, (II) environmental, and (III) ethical policies and practices. | 0.925 |

| Media (Adopted from Park and Cave [4]) | (I) Media plays a pivotal role in maintaining and improving public relations between firms and consumers in the local market. (II) Mass media has a strong power in shaping corporate image and reputation in the local market. (III) Compared with other countries, mass media in Korea pays more attention to the societal role of firms in the local market. | 0.939 |

| Local community (Adopted from Park and Cave [4]) | Local communities expect companies to contribute to society development by (I) volunteering time and effort to local activities. (II) Getting involved in community events in nonfinancial ways. (III) Providing jobs and treating their employees well. | 0.850 |

| NGOs (Adopted from Park et al. [59]) | (I) NGOs police and supervise effectively corporate activities in the local market. (II) NGOs have a propensity to attempt to influence the CSR activities of corporate management by using various instruments. (III) NGO community in the local market has a sufficient power to exert pressure on multinational enterprises to change their behavior and corporate strategy on CSR activities. | 0.903 |

References

- Park, B.-I.; Giroud, A.; Mirza, H.; Whitelock, J. Knowledge acquisition and performance: The role of foreign parents in Korean IJVs. Asian Bus. Manag. 2008, 7, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-C.; Hsiung, H.-H.; Lu, T.-C. Re-examining the relationship between control mechanisms and international joint venture performance: The mediating roles of perceived value gap and information asymmetry. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2015, 20, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Bai, X.; Li, J.-J. The influence of institutional forces on international joint ventures ‘foreign parents’ opportunism and relationship extendedness. J. Int. Market. 2015, 23, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.-I.; Cave, A.-H. Corporate social responsibility in international joint ventures: Empirical examinations in South Korea. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egri, C.-P.; Ralston, D.-A. Corporate responsibility: A review of international management research from 1998 to 2007. J. Int. Manag. 2008, 14, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Cohen, M.-A.; Elgie, S.; Lanoie, P. The Porter hypothesis at 20: Can environmental regulation enhance innovation and competitiveness? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockett, A.; Moon, J.; Visser, W. Corporate social responsibility in management research: Focus, nature, salience and sources of influence. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Building corporate social responsibility into strategy. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2009, 21, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Jamali, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility of Multinational Companies Subsidiaries in Emerging Markets: Evidence from China. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L.-F.; Johnson, P.-J.; Ahmed, U.-Z. International Equity Joint Ventures in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. J. Afr. Bus. 2002, 3, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, A. Determinants of capital structure. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2004, 31, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathert, N. Strategies of legitimation: MNEs and the adoption of CSR in response to host-country institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2016, 47, 858–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Rivers, C. Antecedents of CSR practices in MNCs’ subsidiaries: A stakeholder and institutional perspective. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 86, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.-E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kakabadse, N.-K.; Rozuel, C.; Lee-Davis, L. Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder approach: A conceptual review. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethic 2005, 1, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 87, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.-I.; Ghauri, P.-N. Determinants influencing CSR practices in small and medium sized MNE subsidiaries: A stakeholder perspective. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.-E.; Preston, L.-E.; Sachs, S. Managing the extended enterprise: The new stakeholder view. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Pilar, G.; Belarmino, A. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. J. Operat. Manag. 2010, 28, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikhani, A.; Lee, J.-W.; Ghauri, P.N. Network of MNC’s socio-political behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.-R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Husted, B.-W.; Montiel, I.; Christmann, P. Effects of local legitimacy on certification decisions to global and national CSR standards by multinational subsidiaries and domestic firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2016, 47, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.-J.; Powell, W.-W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.-T.; Eden, L.; Miller, S.-R. Multinationals and CSR: Does distance matter? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Zaheer, S. Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, B.; Kestler, A.; Anand, S. Building local legitimacy into corporate social responsibility: Gold mining firms in developing nations. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.; Allen, D.-B. Corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise: Strategic and institutional approaches. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, F.; Ehrgott, M.; Kaufmann, L.; Carter, C.-R. Local stakeholders and local legitimacy: MNEs’ social strategies in emerging economies. J. Int. Manag. 2012, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.-L.; Ellram, L.M.; Kirchoff, J.-F. Corporate social responsibility reports: A thematic analysis related to supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2010, 46, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayasankar, K. Corporate social responsibility and firm size. J. Bus. Ethic 2008, 83, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies? J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Sanchez, S.-M.; Bosque, I.-R. Understanding corporate social responsibility and product perceptions in consumer markets: A cross-cultural evaluation. J. Bus. Ethic 2007, 80, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, A.; Swan, V.; Johnson, W.-J. Corporate social responsibility: An empirical investigation of U.S. organizations. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 85, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczniak, G.-R.; Murphy, P.-E. Stakeholder theory and marketing: Moving from a firm-centric to a societal perspective. J. Pub. Policy Market. 2012, 31, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, L.-P.; Rubin, R.S.; Dhanda, K.K. The communication of corporate social responsibility: United States and European Union multinational corporations. J. Bus. Ethic 2007, 74, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçkun, S.; Arslan, A.; Yener, S. Could CSR Practices Increase Employee Affective Commitment via Moral Attentiveness? Sustainability 2020, 12, 8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Hou, S.; Li, Q. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Value: The Moderating Effects of Financial Flexibility and R&D Investment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8452. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.-B.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Wu, T.-J.; Peng, C.-L. Employee′s Corporate Social Responsibility Perception and Sustained Innovative Behavior: Based on the Psychological Identity of Employees. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.-W.; Gray, B. Testing a model of organizational response to social and political issues. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 467–498. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, A.-M. Foreign direct investment and environmental regulations: A survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2014, 28, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detomasi, D.-A. The political roots of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethic 2008, 82, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, A.-H. Environmentally responsible management in international business: A literature review. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2014, 22, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.-L.; Ahmad, J. Incorporating stakeholder approach in corporate social responsibility (CSR): A case study at multinational corporations (MNCs) in Penang. Soc. Responsib. J. 2010, 6, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.-N. Sustainable supply chains: A study of interaction among the enablers. Bus. Proc. Manag. J. 2010, 16, 508–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihong, Z.; Goffin, K. Managing the transition—supplier management in international joint ventures in China. Int. J. Physic. Distri. Logist. 2001, 31, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, L.; Su, J.; Zhang, W. Do suppliers applaud corporate social performance? J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 121, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, J.; Rivoli, P. Does ethical investing impose a cost upon the firm? A theoretical perspective. J. Investig. 1997, 6, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.-M.; Shavit, T. How can a ratings-based method for assessing corporate social responsibility (CSR) provide an incentive to firms excluded from socially responsible investment indices to invest in CSR? J. Bus. Ethic 2008, 82, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O′Shaughnessy, K.-C.; Gedajlovic, E.; Reinmoeller, P. The influence of firm, industry and network on the corporate social performance of Japanese firms. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2007, 24, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudal, T. Drivers and barriers of CSR and the size and internationalization of firms. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, K.; Moon, J.; Matten, D. An institution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in multi-national corporations (MNCs): Form and implications. J. Bus. Ethic 2012, 111, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O′Riordan, L.; Fairbrass, J. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Models and theories in stakeholder dialogue. J. Bus. Ethic 2008, 83, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbag, M.; Mirza, H. Factors affecting international joint venture success: An empirical analysis of foreign-local partner relationships and performance in joint ventures in Turkey. Int. Bus. Rev. 2000, 9, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, F.; Samaratunge, R. Responsible entrepreneurship in developing countries: Understanding the realities and complexities. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 90, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugler, P.; Shi, J.Y.-J. Corporate social responsibility for developing country multinational corporations: Lost war in pertaining global competitiveness? J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 87, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamish, P.-W.; Lupton, N. Managing joint ventures. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Investigating stakeholder theory and social capital: CSR in large firms and SMEs. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 91, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Cowley, J. The relevance of stakeholder theory and social capital theory in the context of CSR in SMEs: An Australian perspective. J. Bus. Ethic 2013, 118, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.-I.; Chidlow, A.; Choi, J. Corporate social responsibility: Stakeholders influence on MNEs′ activities. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 966–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.-A.; Graves, S.-B. The corporate social performance—Financial performance link. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.-P.; Guay, T.-R. Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, D.; Lozano, J.-M.; Albareda, L. The role of NGOs in CSR: Mutual perceptions among stakeholders. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 88, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbun, B.-Y. Cannot manage without the ‘significant other’: Mining, corporate social responsibility and local communities in Papua New Guinea. J. Bus. Ethic 2007, 73, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.-N.; Cave, A.-H.; Park, B.-I. The impact of foreign parent control mechanisms upon measurements of performance in IJVs in South Korea. Critl. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2013, 9, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, U.; Kogut, B. Knowledge and the speed of the transfer and imitation of organizational capabilities: An empirical test. Org. Sci. 1995, 6, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Investment Promotion Centre. Database of Approved Investment Projects; Ghana Investment Promotion Centre: Accra, Ghana, 2018.

- Furrer, O.; Egri, C.-P.; Ralston, D.-A.; Danis, W.; Reynaud, E.; Naoumova, I.; Molteni, M.; Starkus, A.; Darde, F.L.; Dabic, M.; et al. Attitudes toward corporate responsibilities in Western Europe and in Central and East Europe. Manag. Int. Rev. 2010, 50, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fetscherin, M.; Alon, I.; Lattemann, C.; Yeh, K. Corporate social responsibility in emerging markets: The importance of the governance environment. Manag. Int. Rev. 2010, 50, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.; Portugal, P. The termination of international joint ventures: Closure and acquisition by domestic and foreign partners. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Political behavior, social responsibility, and perceived corruption: A structuration perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.-M.; MacKenzie, S.-B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.-P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psych. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows; Open University Press: Buckingham, Buckinghamshire, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.-G.; Fidell, L.-S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.-J.; Babin, B.; Money, A.-H.; Samouel, P. Essentials of Business Research Methods; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.-B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah-Tawiah, K.; Dartey-Baah, K. Corporate Social Responsibility in Ghana. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Anku-Tsede, O.; Deffor, E.-W. Corporate Responsibility in Ghana: An Overview of Aspects of the Regulatory Regime. Bus. Manag. Res. 2014, 3, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.-A.; Frempong, G.; Akuffobea, M.; Onumah, J. Contributions of multinational enterprises to economic development in Ghana: A myth or reality? Int. J. Develop. Sustainab. 2017, 6, 2068–2081. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Pofoura, A.K.; Mensah, I.A.; Li, L.; Moshin, M. The Role of Environmental Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development: Evidence from 35 Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, L.; Sun, H.; Farhad, T. Low-Carbon Financial Risk Factor Correlation in the Belt and Road PPP Project; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.; Gunterberg, C.; Larsson, E. Sourcing in an increasingly expensive China: Four swedish cases. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 97, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, R.; Yang, W. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) in China. J. Bus. Ethic 2011, 101, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munilla, L.-S.; Miles, M.-P. The corporate social responsibility continuum as a component of stakeholder theory. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2005, 110, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R. Effects of government regulations, market orientation and ownership structure on corporate social responsibility in China: An empirical study. Int. J. Manag. 2007, 24, 582–591. [Google Scholar]

| Mean | S.D. | Correlation | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |||

| 1.41 | 0.49 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 1.93 | 0.48 | −0.201 * | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2.58 | 0.72 | −0.064 | 0.012 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 1.89 | 0.63 | 0.197 * | −0.079 | −0.053 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2.82 | 0.88 | 0.021 | 0.11 | −0.220 * | 0.176 | 1 | |||||||||

| 4.44 | 0.49 | 0.022 | −0.077 | −0.1 | 0.065 | 0.079 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3.49 | 0.42 | −0.279 ** | −0.057 | 0.138 | 0.09 | 0.062 | 0.258 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 3.48 | 0.59 | 0.089 | −0.033 | −0.235 ** | −0.098 | 0.011 | 0.215 * | 0.053 | 1 | ||||||

| 2.77 | 0.97 | −0.011 | −0.141 | −0.184 * | 0.104 | 0.230 * | 0.107 | −0.05 | 0.153 | 1 | |||||

| 3.84 | 1.0 | 0.084 | −0.121 | −0.154 | −0.036 | 0.192 * | 0.097 | 0.091 | 0.295 ** | 0.098 | 1 | ||||

| 3.80 | 0.61 | 0.179 * | −0.083 | −0.144 | 0.075 | 0.11 | 0.107 | 0.161 | 0.068 | −0.048 | 0.072 | 1 | |||

| 4.12 | 0.87 | 0.119 | 0.421 ** | 0.071 | −0.082 | 0.059 | −0.025 | −0.124 | −0.026 | 0.062 | 0 | 0.347 ** | 1 | ||

| 3.49 | 0.47 | −0.132 | 0.072 | −0.093 | −0.168 | 0.01 | −0.113 | −0.018 | −0.011 | 0.026 | 0.097 | 0.085 | 0.028 | 1 | |

| 3.64 | 0.58 | 0.148 | −0.005 | −0.137 | 0.107 | −0.046 | 0.117 | 0.131 | 0.178 | 0.123 | 0.145 | 0.087 | −0.081 | 0.064 | 1 |

| 3.66 | 0.43 | −0.029 | −0.138 | 0.028 | 0.049 | 0.042 | 0.276 ** | 0.309 ** | 0.320 ** | 0.199 * | 0.241 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.038 | 0.261 ** | 0.119 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development status of MNC origin | −0.103 * | −0.017 | −0.158 ** | −0.061 | 1.422 |

| Ownership structure | 0.062 | 0.140 | 0.083 | 0.078 | 1.142 |

| Institutional distance | −0.074 * | −0.105 * | −0.133 * | −0.180 * | 1.536 |

| Subsidiary size | 0.041 | 0.063 | 0.070 | 0.078 | 1.327 |

| Subsidiary age | −0.106 | −0.044 | −0.075 | −0.019 | 1.391 |

| Consumers | 0.276 *** | 0.317 *** | 0.202 *** | 1.598 | |

| Internal managers and employees | 0.156 * | 0.118 | 0.195 ** | 1.916 | |

| Government | 0.061 | 0.034 | 0.077 | 1.178 | |

| Suppliers | 0.012 | 0.073 | 0.091 | 1.329 | |

| Investors | 0.071 | 0.054 | 0.066 | 1.132 | |

| Competitors | 0.246 *** | 0.185 ** | 0.069 | 1.167 | |

| Media | 0.027 | 0.048 | 1.364 | ||

| Local Community | 0.249 *** | 0.260 *** | 1.643 | ||

| NGO | 0.098 | 0.065 | 1.094 | ||

| Internal managers and employees X Competitors | −0.206 ** | ||||

| Adjusted R² | 0.413 | 0.327 | 0.567 | 0.582 | |

| F | 21.649 *** | 18.526 *** | 29.985 *** | 35.694 *** |

| Hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|

| Support |

| Partially Support |

| Reject |

| Reject |

| Reject |

| Support |

| Reject |

| Support |

| Reject |

| Support |

| Support |

| Number | Mean | S.D. | F-Ratio | Significance Level (Sig.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign parent majority ownership | 103 | 3.731 | 0.390 | 14.719 | 0.000 |

| Equal ownership split | 10 | 3.375 | 0.480 | ||

| Local parent majority ownership | 8 | 3.031 | 0.240 |

| IJVs (N = 121) | WOSs (N = 124) | Significance Level (Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.920) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.81 | 3.97 | 0.007 |

| 3.75 | 3.87 | 0.075 |

| 3.52 | 3.72 | 0.003 |

| 3.65 | 3.88 | 0.000 |

| 3.73 | 3.91 | 0.000 |

| 3.91 | 4.10 | 0.000 |

| 3.52 | 3.78 | 0.000 |

| 3.71 | 3.81 | 0.051 |

| 3.47 | 3.66 | 0.008 |

| 3.62 | 3.79 | 0.001 |

| 3.60 | 3.81 | 0.000 |

| 3.57 | 3.88 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, G.; Pekyi, G.D.; Chen, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, X. Sustainability-Conscious Stakeholders and CSR: Evidence from IJVs of Ghana. Sustainability 2021, 13, 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020639

Tian G, Pekyi GD, Chen H, Sun H, Wang X. Sustainability-Conscious Stakeholders and CSR: Evidence from IJVs of Ghana. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020639

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Gang, Gabriel Dodzi Pekyi, Haojia Chen, Huaping Sun, and Xiaoling Wang. 2021. "Sustainability-Conscious Stakeholders and CSR: Evidence from IJVs of Ghana" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020639

APA StyleTian, G., Pekyi, G. D., Chen, H., Sun, H., & Wang, X. (2021). Sustainability-Conscious Stakeholders and CSR: Evidence from IJVs of Ghana. Sustainability, 13(2), 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020639