Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: Three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification

Abstract

:1. Introduction

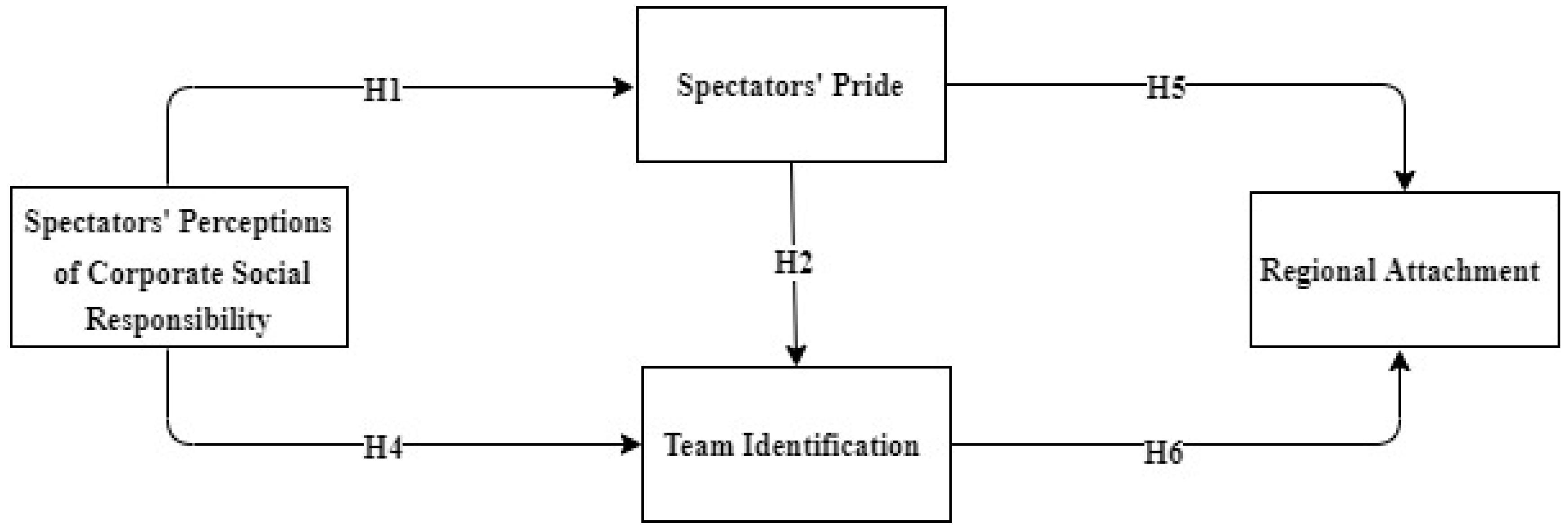

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Spectators’ Pride, and Team Identification (TI)

2.2. Spectators’ Pride and Regional Attachment (RA)

2.3. Influence of Team Identification (TI) on Regional Attachment (RA)

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Regional Attachment (RA)

3.2.2. Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

3.2.3. Spectators’ Pride (SP)

3.2.4. Team Identification (TI)

4. Results

4.1. Correlational Analysis and Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walzel, S.; Robertson, J.; Anagnostopoulos, C. Corporate social responsibility in professional team sports organizations: An integrative review. J. Sport Manag. 2018, 32, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport Events (Asia): Statista Market Forecast. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/272/101/sport-events/asia (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Trendafiova, S.; Ziakas, V.; Sparvero, E. Linking corporate social responsibility in sport with community development: An added source of community value. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, A.; Talebpour, M.; Andam, R.; Kazemnejad, A. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility in Sport Industry: Development and Validation of Measurement Scale. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2017, 5, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.J.; Ko, Y.J.; Connaughton, D.P.; Kang, J.H. The effects of perceived CSR, pride, team identification, and regional attachment: The moderating effect of gender. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, S.; Trendafilova, S.; Daniell, R. Did the 2012 World Series positively impact the image of Detroit?: Sport as a transformative agent in changing images of tourism destinations. J. Sport Tour. 2014, 19, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, J.; Zimbalist, A. The Economic Impact of Sports Facilities, Teams and Mega-Events. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2006, 39, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Milito, M.C.; Nunkoo, R. Residents’ support for a mega-event: The case of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, Natal, Brazil. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Place Attachment, Perception of Place and Residents’ Support for Tourism Development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 188–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, A. The farm as an educative tool in the development of place attachments among Irish farm youth. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 2017, 38, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Decrop, A.; Derbaix, C. Pride in contemporary sport consumption: A marketing perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouthier, M.H.J.; Rhein, M. Organizational pride and its positive effects on employee behavior. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manage. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, L.K.; Tunney, R.J.; Ferguson, E. Does gratitude enhance prosociality?: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 601–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C. Corporate social responsibility: A consumer psychology perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Daryanto, A.; Soopramanien, D. Place attachment, trust and mobility: Three-way interaction effect on urban residents’ environmental citizenship behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 105, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.D. Is Out of Sight out of Mind? Place Attachment among Rural Youth Out-Migrants. Sociol. Rural. 2018, 58, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradish, C.; Joseph Cronin, J. Corporate social responsibility in sport. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; House, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskentli, S.; Sen, S.; Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of CSR domains. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.C. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The Effects of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.F.; Beck, J.T.; Henderson, C.M.; Palmatier, R.W. Building, measuring, and profiting from customer loyalty. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 790–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colicev, A.; Malshe, A.; Pauwels, K.; O’Connor, P. Improving consumer mindset metrics and shareholder value through social media: The different roles of owned and earned media. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. J. Mark. 2012, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Italian tourism intermediaries: A social network analysis exploration. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Social network analysis: Organizational implications in tourism management. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.J.; Schneider, R.C.; Connaughton, D.P.; Hager, P.F.; Ju, I. The effect of nostalgia on self-continuity, pride, and intention to visit a sport team’s hometown. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 23, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkower, Z.; Mercadante, E.J.; Tracy, J.L. How affect shapes status: Distinct emotional experiences and expressions facilitate social hierarchy navigation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 33, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkee, P.K.; Lukaszewski, A.W.; Buss, D.M. Pride and shame: Key components of a culturally universal status management system. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2019, 40, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-Y.; Tong, E.M.W.; Jia, L. Authentic and hubristic pride: Differential effects on delay of gratification. Emotion 2016, 16, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.T.; Tracy, J.L.; Henrich, J. Pride, personality, and the evolutionary foundations of human social status. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2010, 31, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septianto, F.; Seo, Y.; Errmann, A.C. Distinct Effects of Pride and Gratitude Appeals on Sustainable Luxury Brands. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, A.A.; Funk, D.C.; Ridinger, L.; Jordan, J. Sport involvement: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, K.; Fechner, D.; Inoue, Y. Charity sport event participants and fundraising: An examination of constraints and negotiation strategies. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Babiak, K. The role of social responsibility, philanthropy and entrepreneurship in the sport industry. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.K.; Overton, H.; Hull, K.; Choi, M. Examining public perceptions of CSR in sport. Corp. Commun. 2018, 23, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelladurai, P. Corporate Social Responsibility and Discretionary Social Initiatives in Sport: A Position Paper. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2016, 1, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenisek, T.J. A conceptualization based on organizational literature. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jetten, J.; Spears, R.; Manstead, A.S.R. Similarity as a source of differentiation: The role of group identification. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, D.L.; Waddill, P.J.; Brasher, M.; Ladd, S. Examining Sport Team Identification, Social Connections, and Social Well-being among High School Students. J. Amat. Sport 2015, 1, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branscombe, N.R.; Wann, D.L. The Positive Social and Self Concept Consequences of Sports Team Identification. J. Sport Soc. Issues 1991, 15, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gau, L.S.; Kim, J.C. The influence of cultural values on spectators’ sport attitudes and team identification: An eastwest perspective. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2011, 39, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Renk, U.; Mishra, A. Exploring the impact of employees’ self-concept, brand identification and brand pride on brand citizenship behaviors. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Shariff, A.F.; Cheng, J.T. A naturalist’s view of pride. Emot. Rev. 2010, 2, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carver, C.S.; Sinclair, S.; Johnson, S.L. Authentic and hubristic pride: Differential relations to aspects of goal regulation, affect, and self-control. J. Res. Pers. 2010, 44, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swanson, S.; Kent, A. Passion and pride in professional sports: Investigating the role of workplace emotion. Sport Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, M.; Kent, A. Do fans care? Assessing the influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer attitudes in the sport industry. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 743–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Morgan, A.; Assaker, G. Examining the relationship between sport spectator motivation, involvement, and loyalty: A structural model in the context of Australian Rules football. Sport Soc. 2020, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Mills, H.; Lee, C.; Soscia, I. Team identification, discrete emotions, satisfaction, and event attachment: A social identity perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory in organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, D.; Taylor, T.; Funk, D.; Darcy, S. Exploring the development of team identification. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lock, D.; Heere, B. Identity crisis: A theoretical analysis of ‘team identification’ research. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Funk, D.C.; James, J.D. Consumer loyalty: The meaning of attachment in the development of sport team allegiance. J. Sport Manag. 2006, 20, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.J.; Trail, G.T. Relationships among spectator gender, motives, points of attachment, and sport preference. J. Sport Manag. 2005, 19, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.H.; Trail, G.T.; Anderson, D.S. Are Multiple Points of Attachment Necessary to Predict Cognitive, Affective, Conative, or Behavioral Loyalty? Sport Manag. Rev. 2005, 8, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N.D.; Koustelios, A.; Robinson, L.; Barlas, A. Moderating role of team identification on the relationship between service quality and repurchase intentions among spectators of professional sports. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2009, 19, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Robert, L.P. Emotional attachment, performance, and viability in teams collaborating with embodied physical action (EPA) robots. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2018, 19, 377–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.S.; Trail, G.T.; Anderson, D.F. An examination of team identification: Which motives are most salient to its existence? Int. Sport. J. 2002, 6, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Heere, B.; James, J.D. Sports teams and their communities: Examining the influence of external group identities on team identity. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.D.; Donavan, D.T. Human Brands in Sport: Athlete Brand Personality and Identification. J. Sport Manag. 2013, 27, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.; Rosenberger, P.J. The influence of involvement, following sport and fan identification on fan loyalty: An Australian perspective. Int. J. Sport. Mark. Spons. 2012, 13, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Wann, D.L.; Ko, Y.J. Influence of team identification, game outcome, and game process on sport consumers’ happiness. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wann, D.L.; Inoue, Y. The effects of implicit team iden- tification ( iTeam ID) on revisit and WOM intentions: A moderated mediation of emotions and flow. J. Sport Manag. 2018, 32, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehmood, K.; Baghoor, G.K.K.; Ali, K. A comparison of motivational desires and motivational outcomes: Study of employees of telecommunication sector organizations. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 5, 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, P.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.-K.; Yi, Y.; Bagozzi, R.P. Effects of Customer Participation in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Programs on the CSR-Brand Fit and Brand Loyalty. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, R.; Kennett-Hensel, P. How expectations and perceptions of corporate social responsibility impact NBA fan relationships. Sport Mark. Q. 2016, 25, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Elasri-ejjaberi, A.; Aparicio-chueca, P.; Triadó-Ivern, X.M. An Analysis of the Determinants of Sport Expenditure in Sports Centers in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallatah, F.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Read, E.A. The effects of authentic leadership, organizational identification, and occupational coping self-efficacy on new graduate nurses’ job turnover intentions in Canada. Nurs. Outlook 2017, 65, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. How does corporate association influence consumer brand loyalty? Mediating role of brand identification. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, E.; Salman, G.G.; Tatoglu, E. An integrative framework linking brand associations and brand loyalty in professional sports. J. Brand Manag. 2008, 15, 336–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.R.; Heere, B.; Shapiro, S.; Ridinger, L.; Wear, H. The displaced fan: The importance of new media and community identification for maintaining team identity with your hometown team. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, G.; Scott, R.S. A model of fan identification: Antecedents and sponsorship outcomes. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Fu, X.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D.A. The Influence of Place Attachment on Social Distance: Examining Mediating Effects of Emotional Solidarity and the Moderating Role of Interaction. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 828–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.; Novicevic, M.M. The impact of hypercompetitive “timescapes” on the development of a global mindset. Manag. Decis. 2001, 39, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Kimmitt, J.; Kibler, E.; Farny, S. Living on the slopes: Entrepreneurial preparedness in a context under continuous threat. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Fink, M.; Lang, R.; Muñoz, P. Place attachment and social legitimacy: Revisiting the sustainable entrepreneurship journey. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2015, 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajrami, D.D.; Radosavac, A.; Cimbaljević, M.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, Y.A. Determinants of residents’ support for sustainable tourism development: Implications for rural communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguztimur, S.; Akturan, U. Synthesis of City Branding Literature (1988–2014) as a Research Domain. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. Progress in sports tourism research? A meta-review and exploration of futures. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernández, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.M.; Connaughton, D.P.; Ju, I.; Kim, J.; Kang, J.-H. The Impact of Self-Continuity on Fans’ Pride and Word-of-Mouth Recommendations: The Moderating Effects of Team Performance and Social Responsibility Associations. Sport Mark. Q. 2019, 28, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Yoon, Y. Online webcast demand vs. Offline spectating channel demand (Stadium and TV) in the professional sports league. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despiney, B.; Karpa, W. Estimating Economic Regional Effects of Euro 2012: Ex-ante and Ex-post Approach. Manag. Bus. Adm. Cent. Eur. 2014, 22, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. The mega-event syndrome: Why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Analysis of hospitality, leisure, and tourism studies in Chile. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet, P.; Bodet, G.; Bernache-Assollant, I.; Kada, F. Segmenting sport spectators: Construction and preliminary validation of the Sporting Event Experience Search (SEES) scale. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H.; Arne Solberg, H. Attracting Major Sporting Events: The Role of Local Residents. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2006, 6, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabuig Moreno, F.; Prado-Gascó, V.; Crespo Hervás, J.; Núñez-Pomar, J.; Añó Sanz, V. Spectator emotions: Effects on quality, satisfaction, value, and future intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1445–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.; Kent, A. Fandom in the workplace: Multi-target identification in professional team sports. J. Sport Manag. 2015, 29, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, M.; Heere, B.; Gordon, B. Predicting Behavioral Loyalty through Community: Why Other Fans Are More Important Than Our Own Intentions, Our Satisfaction, and the Team Itself. J. Sport Manag. 2015, 29, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, K.; Funk, D.; O’Brien, D. The antecedents and outcomes of attachment and sponsor image within charity sport events. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 24, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.D.; Kolbe, R.H.; Trail, G.T. Psychological Connection to a New Sport Team: Building or Maintaining the Consumer Base? Sport Mark. Q. 2002, 11, 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, M.P.; Stinson, J.; Patton, E. Affinity and Affiliation: The Dual-Carriage Way to Team Identification. Sport Mark. Q. 2010, 19, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Anseel, F.; Lievens, F.; Schollaert, E.; Choragwicka, B. Response rates in organizational science, 1995–2008: A meta-analytic review and guidelines for survey researchers. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Begum, S.; Xia, E.; Mehmood, K.; Iftikhar, Y.; Li, Y. The Impact of CEOs’ Transformational Leadership on Sustainable Organizational Innovation in SMEs: A Three-Wave Mediating Role of Organizational Learning and Psychological Empowerment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 2, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwon, H.H.; Trail, G.; James, J.D. The Mediating Role of Perceived Value: Team Identification and Purchase Intention of Team-Licensed Apparel. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Mehmood, K.; Paulsen, N.; Ma, Z.; Kwan, H.K. Why Safety Knowledge Cannot be Transferred Directly to Expected Safety Outcomes in Construction Workers: The Moderating Effect of Physiological Perceived Control and Mediating Effect of Safety Behavior. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04020152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Li, Y.; Jabeen, F.; Khan, A.N.; Chen, S.; Khalid, G.K. Influence of female managers’ emotional display on frontline employees’ job satisfaction: A cross-level investigation in an emerging economy. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1491–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Rütter, N. Is satisfaction the key? The role of citizen satisfaction, place attachment and place brand attitude on positive citizenship behavior. Cities 2014, 38, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C.; De Piccoli, N. Place attachment, identification and environment perception: An empirical study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.; Healey, M. Place attachment and place identity: First-year undergraduates making the transition from home to university. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antonsich, M.; Holland, E.C. Territorial attachment in the age of globalization: The case of Western Europe. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 21, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmo, G.C.; Arcese, G.; Valeri, M.; Poponi, S.; Pacchera, F. Sustainability in tourism as an innovation driver: An analysis of family business reality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | AVE | CR | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Spectators’ gender | 1.77 | 0.419 | ||||||||

| 2. Spectators’ age | 1.95 | 0.933 | 0.092 * | |||||||

| 3. Regional attachment | 4.061 | 0.943 | 0.927 | 0.891 | 0.072 | 0.022 | (0.96) | |||

| 4. Corporate social responsibility | 4.080 | 0.617 | 0.636 | 0.839 | 0.045 | 0.008 | 0.444 ** | (0.83) | ||

| 5. Spectators’ pride | 3.536 | 1.041 | 0.600 | 0.818 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.209 ** | 0.158 ** | (0.81) | |

| 6. Team identification | 4.264 | 0.517 | 0.632 | 0.872 | 0.013 | 0.049 | 0.299 ** | 0.196 ** | 0.138 ** | (0.85) |

| Measurement Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized Four Factors Model | 118.271 | 62 | 1.908 | 0.986 | 0.981 | 0.042 |

| Three Factors Model-3 CSR and RA | 669.740 | 71 | 9.433 | 0.867 | 0.896 | 0.129 |

| Three Factors Model-2 TI and RA | 740.907 | 71 | 10.435 | 0.851 | 0.844 | 0.136 |

| Three Factors Model-1 SP and RA | 791.248 | 71 | 11.144 | 0.840 | 0.875 | 0.141 |

| Single Factor Model | 1587.638 | 70 | 22.361 | 0.663 | 0.737 | 0.205 |

| Relationships between CSR, SP, TI, and RA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | TI | RA | |||||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| Variables | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) |

| Constant | 3.45 *** (0.22) | 2.39 *** (0.36) | 4.28 *** (0.11) | 3.63 *** (0.18) | 4.04 *** (0.13) | 3.74 *** (0.19) | 3.10 *** (0.23) | 3.74 *** (0.37) | 1.40 *** (0.20) |

| Spectators’ gender | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Spectators’ age | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) |

| CSR | 0.27 *** (0.08) | 0.17 *** (0.05) | |||||||

| SP | 0.14 ** (0.03) | 0.19 *** (0.04) | |||||||

| TI | 0.54 *** (0.08) | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.071 | 0.345 | 0.479 | 0.084 | 0.269 | 0.097 | 0.425 |

| ΔR2 | 0.17 | 0.274 | 0.134 | 0.185 | 0.328 | ||||

| F | 2.73 * | 13.03 *** | 5.08 *** | 20.21 *** | 36.72 *** | 8.02 *** | 23.08 *** | 3.90 *** | 50.23 *** |

| IV | MV | DV | Effect of IV on M (a) | Effect of M on DV (b) | Indirect effect (a × b) | Total effects (c’) | Total effects (c) | 95% CI | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | SP | TI | 0.16 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.02 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.16 ** | (0.0012, 0.0321) | Yes |

| SP | TI | RA | 0.14 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.07 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.19 ** | (0.0081, 0.0679) | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ullah, F.; Wu, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Jabeen, F.; Iftikhar, Y.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Kwan, H.K. Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: Three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification. Sustainability 2021, 13, 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020597

Ullah F, Wu Y, Mehmood K, Jabeen F, Iftikhar Y, Acevedo-Duque Á, Kwan HK. Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: Three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):597. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020597

Chicago/Turabian StyleUllah, Farman, Yigang Wu, Khalid Mehmood, Fauzia Jabeen, Yaser Iftikhar, Ángel Acevedo-Duque, and Ho Kwong Kwan. 2021. "Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: Three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020597