1. Introduction

Over the past twenty years, the intensification of global processes in companies, the speed of globalization, the emergence of new markets, technological and economic developments, the decline of barriers to entry into international markets, the need for new consumers among other aspects, [

1,

2] they made the internationalization process more and more executed within the corporations, but at the same time, it made it much more complex, due to the addition of so many variables and their rapid transformations [

3]. Analyzing the context of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), this scenario becomes even more complex, in the course of they enter the international market, usually through B2B commercial models, pressured by competitiveness, seeking in the process, an alternative for growth and sustainability of its business model [

4,

5].

Internationalization in SMEs acts as a learning process for the organization, which requires the development of flexible, dynamic, and effective capacities and skills that can respond quickly to market changes [

6,

7]. Marketing capabilities are identified as potential influencers in an organization’s international marketing performance [

8,

9,

10]. Developing marketing capabilities, it is possible to build strong positioning and deliver value to consumers to maintain their loyalty, important factors in the contribution of the performance of the organization [

11]. In this study, two capabilities will be analyzed, namely dynamic marketing capabilities (DMC) and adaptive marketing capabilities (AMC). Precisely because of the changeable, transformative, and often turbulent character of the capabilities, researchers understand the DMC [

12,

13,

14,

15], in which they are responsible and efficient in connecting the company’s internal processes, creating, and delivering value to the consumer in the face of market changes, it works as a response to market changes and needs [

16,

17,

18]. The AMC, which bears as a characteristic the organization’s ability to be proactive about the actions in the market; that is, the company is constantly studying the market, whether international or not, its consumers and consequently the marketing [

19]. Combined with the action in the B2B market, the organization’s marketing capabilities have much more challenging, when consumers are found who focus more on aspects related to the price and performance of the products they purchase [

20]. Another challenge for SMEs in international markets concerns the intensity of competitiveness, when the higher it is, the more effective and dynamic the organization’s strategies must be [

21], either by the presence of more demanding and selective consumers [

22] or the pressure exerted by competitors [

23].

Although the impact of DMC and AMC on marketing performance found in the literature [

24,

25], several questions remain unanswered. More precisely, marketing literature gives relatively less attention to the impact of both marketing capabilities on the internationalization process, especially for SMEs in the B2B sector [

4,

11,

26].

In this study, we proposed to analyze the influence of the two marketing capacities, DMC and AMC, in the international marketing performance of Portuguese SMEs that operate in B2B commercial relations, through the theory of resource advantage (R-A), precisely because it encourages the constant renewal of organization based on the valorization of its competences and capacities [

19,

27], particularly those related to marketing. The same variables were also analyzed based on the competitive intensity that was framed. To this end, we have surveyed 335 Portuguese SMEs with B2B business relationships and to test the hypotheses presented here, multiple hierarchical regressions were applied. As for the analysis of high and low competitive intensity environments, dummies were produced in order to present the moderation of the two environments in the variables.

Concerning the structure of the present research,

Section 2 is composed of the theoretical foundation regarding the dynamic marketing capabilities, adaptive marketing capabilities, international marketing performance, competitive intensity, and the development of the hypotheses. In the following

Section 3, the methodology followed is addressed. In

Section 4 we present the hypotheses testing and the empirical results. Subsequently,

Section 5 and

Section 6 contain the discussion and conclusion of the research, respectively. Finally, in

Section 6.1 we address the limitations and future research avenues.

2. Theorical Foundation

The growing trend of globalization of markets and the consequent increase in the intensity of competition has led to the emergence of new strategies within companies, to equate the performance in international trade [

28,

29]. In order to extract all the potential benefits of the new market, the organization must be internally endowed with strong resources, which can be defined as assets, capabilities, organizational processes, attributes, information, and knowledge of the company [

1,

30], which acquires and improves throughout its existence. The presence of these resources are fundamental points for the implementation of the internationalization of companies, and organizations need to be able to transfer these resources to the foreign market [

1,

31,

32], especially when dealing with SMEs that, due to their characteristics and dimensions, consequently, have a lower proportion of resources, skills, and capacities, and normally fail to evaluate the market as a whole, failing to fully explore international opportunities [

33].

At the same time, SMEs can present potential relation with the growth of the competitive advantage in the market, either by their capacity for flexibility and by their ability to respond more quickly to market changes [

6,

7]. The constant development of the quality of the attributes of the company is fundamental for the construction of the competitive advantage, either through its products, processes, flexibility in relation to the market [

34], aiming at a positive integration between internal and external business environments [

35]. To build a sustainable competitive advantage and a performance superior to high competition, companies need to have the resources that are oriented as requirements of the international environment, through the search for new business opportunities, new markets, adaptation, and creation of products to new consumers/markets [

28]. The impact of the dynamics of these capacities on the organization, becoming a competitive advantage in the international market [

36], are crucial to raise the positive advantages in international marketing performance [

37]. Following the R-A theory, how companies should seek heterogeneous resources, or a diversity of resources, based on an analysis of their competitors’ resources, thus obtaining different performances within the same market [

19,

27,

28]. These advantages arise from the value perceived by the consumer in relation to the amount invested in the acquisition [

38].

With the presence of increasingly demanding consumers in the market, building a strong competitive advantage becomes more challenging for the organization [

21]. Building a competitive advantage is essential, as studies show that competitiveness and its intensity influence the organization’s performance [

21,

39], when the higher their presence, they have stronger effects on performance [

40]. Although there are differences between more or less competitive environments, which the lesser intensity leads the organization not to be so pressured to adapt to its strategies, allowing time and dedication for the organization to offer greater value delivery to the consumer [

41], space to find opportunities and resources in the new market [

26]. With the increase in competitive intensity, offers become more scarce and determinant for the company’s success or failure in the international market [

21].

Considering the skills and competencies of an organization, which help to understand the fast changes of the global market, the marketing capacities need to be grouped in order to bring relevant information from the new market, generating and managing the bonds built with customers and interested parties [

42,

43,

44]. It is precisely in these principles of market change that the development of dynamic marketing capabilities; that is, they are different marketing tools capable of connecting and transforming the organization’s internal resources, creating and delivering value to the consumer, in the face of such transformations in the market [

45], needs to be developed by companies that are or intend to internationalize. Dynamic capabilities are seen as a response to changing market needs [

17,

18]. Such capabilities can be seen from the emergence of new products/services, more efficient processes, or any other change that aims to respond to the international market itself [

12,

46].

Having the ability to identify, understand and respond to the needs of customers in the international market is one of the foundations for establishing a connection with it and, when established, they are essential for creating competitive advantage in the market [

16,

43,

47]. Dynamic capabilities are named precisely for their characterization, the multifunctional processes, product development management, the supply chain and its customers are appropriate, the situations presented in the market [

12,

26]. Based on these findings in the literature, the following hypotheses were raised for this research:

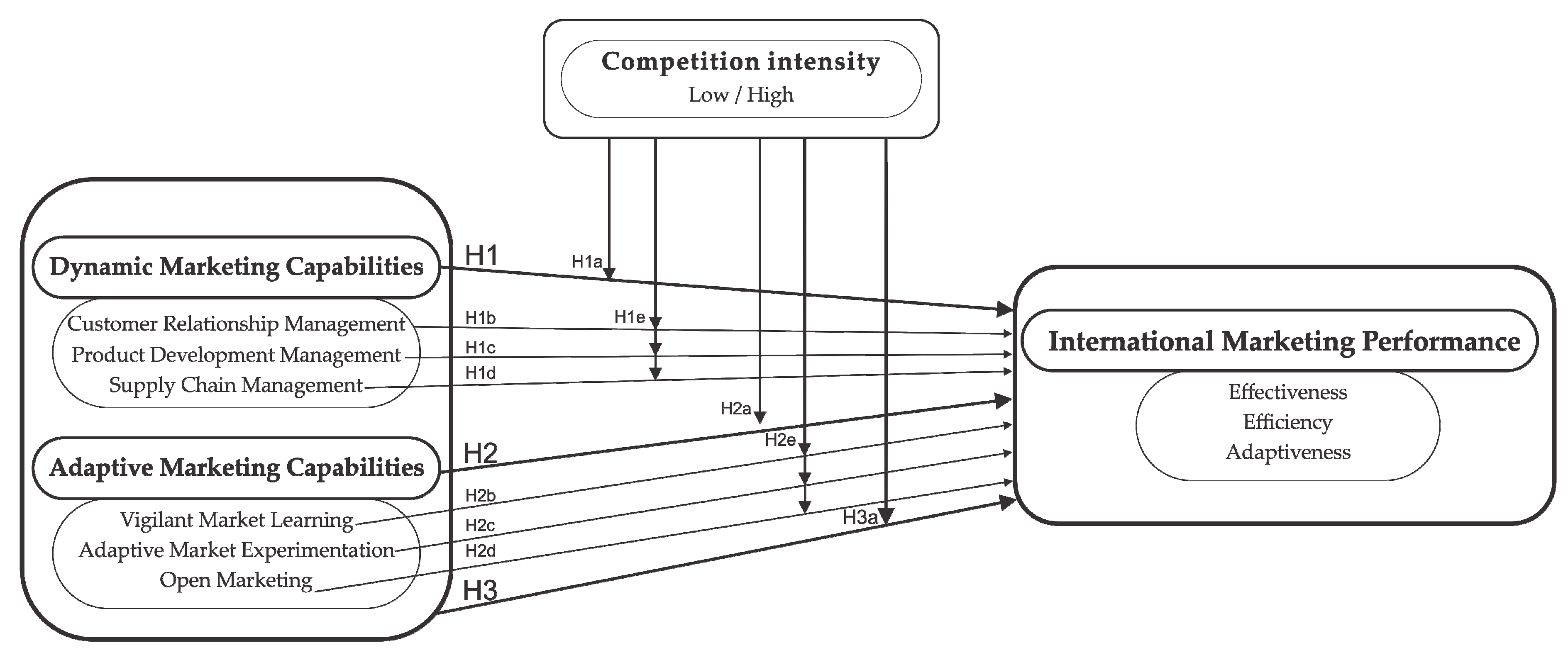

Hypotheses 1 (H1).There is a positive relationship between Dynamic Marketing Capabilities and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 1 (H1a).The relationship between DMC and IMP is stronger when CI is higher.

Hypotheses 1 (H1b).There is a positive relationship between Customer Relationship Management and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 1 (H1c).There is a positive relationship between Product Development Management and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 1 (H1d).There is a positive relationship between Supply Chain Management and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 1 (H1e).The relationship between (1) DCRM, (2) DPDM, (3) DSCM, and IMP is stronger when CI is higher.

The opening of the markets in the last two decades has brought to the global market the competition of the old and new entrants from the disintegration of the barriers of access to certain previously closed markets [

48]. With such changes, it is necessary that the organization, when assuming an international objective, needs to adapt its own culture, since it is not abroad to take advantage of only one specific opportunity, but must think about the sustainability of this business [

1,

3,

49]. The exploitation of external resources and capabilities, achieving integration and cooperation between the integrated contact network with internal resources, transforms the company’s capabilities into adaptable aspects [

17,

50].

Following the three components in the composition of adaptive marketing capabilities, first, it allows the organization to be attentive to the market, anticipating possible opportunities, flexing its strategy, adapting proactively when it comes to the future development of the market, resulting in a performance superior to its competitors and reducing disparities between the response issued by the company and changes in the market [

26,

51]. Second, the adaptability of marketing capabilities allows the acquisition of learning and experimentation resources, whether through the accumulation of knowledge or the development of the market itself [

17]. The third component helps to build more stable relationships through more open marketing, active in the different social networks that companies frequent [

17]. The existence of open networks of contacts helps the company on the degree of access to resources, bringing together skills that include the strengthening of long-term partnerships and, consequently, the achievement of results [

52]. This capacity differs from dynamics, although both act in terms of market changes, there is a delay in identifying the change and in the effective response given to such a transformation [

12]. Adaptive marketing capabilities respond to the market faster than dynamic ones [

17,

19]. It allows a company to detect, interpret and act on these critical signals in its business environment, faster than competitors, leading to a significant competitive advantage [

53] and influential in international marketing performance. Because of this, the following hypothesis is elaborated:

Hypotheses 2 (H2).There is a positive relationship between Adaptive Marketing Capabilities and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 2 (H2a).The relationship between AMC and IMP is stronger when CI is higher.

Hypotheses 2 (H2b).There is a positive relationship between Vigilant Market Learning and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 2 (H2c).There is a positive relationship between Adaptive Market Experimentation and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 2 (H2d).There is a positive relationship between Open Marketing and International Marketing Performance.

Hypotheses 2 (H2e).The relationship between (1) AVIG, (2) AADP, (3) AMKT, and IMP is stronger when CI is higher.

We also understand in a grouped way that the marketing capabilities, defined here as DMC and AMC, influence the international performance of the organization, precisely because of the changeable, transformative and often turbulent character of marketing capabilities [

12,

13,

14,

15], in which they are responsible and efficient in connecting the company’s internal processes, creating and delivering value to the consumer in the face of market changes, it works as a response to market changes and needs [

16]. Within the literary context, authors suggest that organizations can find in their marketing skills, strengths to develop their competitive positioning, essential in markets with high competitive intensity improve the delivery of value to the consumer and maintain or increase their loyalty to the brand, generating, therefore, reinforcements in the results of organizational performance [

54]. Because of this, the following hypothesis is elaborated:

Hypotheses 3 (H3).DMC and AMC have a joint positive impact on IMP.

Hypotheses 3 (H3a).The joint positive impact of DMC and AMC on IMP is stronger when CI is higher.

5. Discussion

The perceived relationships between the DMC variable and IMP are seen in the literature through the constant need for marketing capabilities to be at the level of market transformations [

12,

13], results that meet the concepts from the R-A theory, which promotes dynamism, the organization’s proactivity in being focused on supporting superior market performances [

19]. DMC encourage the organization to adjust quickly, reallocating its internal resources to better match market needs and demands [

26,

81] and it is responsible for connecting the different processes of the organization to deliver value to the consumer in the face of such changes [

17,

18], which makes it a potential influencer in the international marketing performance of the organization. As shown in

Table 8, it is possible to confirm that the variable DMC has a significant impact on the performance of the organization, which is consistent with other previous studies [

12,

14,

26,

46]. As pointed out in the results, product development management has positive effects on IMP, which are justified by the relationship model established between brand and customer (B2B), consider its capacity for innovation, in the development of new products/services, as well as the construction of optimized management of them, essential aspects for the construction of a market differential [

82], but also by the value perceived by the customer; that is, the valuation of the price x performance aspect of purchased products [

20] soon we were able to understand why this aspect is positively so strongly related to performance [

83].

Due to the characteristics of the international B2B market, which structurally differs from the B2C model, due to the identification and accessibility of customers, the level of demand for products, and knowledge of the market, which require the organization in a B2B context, the constant construction of customized solutions combined with managing relationships with customers and stakeholders [

20,

84,

85] why supply chain management has positive effects on IMP, that operates on the integration of the organization’s different processes with suppliers, their selection and qualification, aspects that make the company more effective and with better performance [

86].

According to the literature, AMC is responsible for the organization’s proactive skills, that it feels and acts in the face of the signals that the market transmits, constantly learning from market experiences, coordinating internal resources to respond quickly to these changes [

17,

26]. This capacity is an asset for organizations in the international market, as it has a strong capacity to exploit external resources to develop the organization in a new market so that the three components that make up AMC are considered influential in the organization’s performance [

26]. Through the characteristics of the two components that had positive effects on IMP, in which the company has the ability to observe the market in order to be quicker to perceive opportunities and promoting anticipation about competitors (vigilant market learning) [

26,

51] and the component to assists in building relationships by opening up communication with partners, exchanging technologies and mobilizing skills of current partners (open marketing) [

17,

26], it is possible to perceive, due to the volatility of the international B2B market [

20] and the need for organizations to be in constant evolution, once again aligned with the purposes of the R-A theory [

28], it is possible to understand the reasons that justify their influences.

There are two ways of operating from the perspective of the intensity of competitiveness when it is low-grade, when the company can capitalize and operate its behavior and trends in relation to the competition [

87,

88]. To a lesser extent, the internationalization process can be carried out with total focus, and activities such as exporting processes, acquiring information, innovating, and developing products and services will be carried out more easily; consequently, we find a potential increase in international operations due to facilitation gap found in a competition [

89]. The second way is when this intensity is high, where there is a level of uncertainty about the strategies and the acquisition of relevant information is necessary to minimize the risks of internationalization [

90], proactive activities adapted to the market are necessary [

91]. We observed in the results that the fourth components have effects on positivity when they are in a deviated low-intensity environment (DCRM, DSCM, AVIG, and AMKT) and two in a low-intensity environment (DPDM and AMKT), and despite being a complex job for the organization, according to [

92], this intense competitiveness increases the capacity for innovation, requiring companies to find new ways to compete in a more competitive market. Such paths, in this study, are perceived from the constant innovation and management of the products offered in the international B2B market and the evolution regarding the construction of opportunities in search of opportunities. It must be remembered that performance is not the exclusive result of competitive intensity, so companies with high or low performance should not suffer such effects if differentiation and efficiency marketing actions are applied to the international market [

89]. In general, competition in international markets requires companies to develop or acquire capabilities that include, for example, obtaining information about the market, identifying potential customers and making timely contacts in the international market to establish partnerships [

93].

Interestingly, the relative dynamics of these effects change when the competitive environment becomes more or less intense. DMC has an equal impact on the company’s performance in low and high competitive intensity, although its characteristics are not as agile and dynamic as AMC, it still proves to be important as an influencing tool, suggesting that the market transformations themselves, technology and consumer preference in the B2B market, have space for the development of DMCs in view of the results obtained in their performance. On the contrary, an AMC has positive effects on international marketing performance only in environments with high competitive intensity, suggesting that its evolutionary characteristics of dynamic characteristics, operate in greater effect on performance, when competing with other associations that also already have the knowledge of the market, of consumers and already obtained in times of operation, the necessary resources to establish a common business.

This study showed the impact of DMC and AMC on the international marketing performance of Portuguese SMEs that operate in the B2B market. Through the analysis obtained, the need for organizations to develop marketing skills is evident [

94] that are dynamic and adaptable to each new international market, such capabilities are not only allow for effective organization performance [

1,

3]. Such complexities and barriers that can impede the growth of an SME in the foreign market, can use all the tools of the marketing capacities with the intention of business sustainability [

6]. Another interesting finding found in this study, concerns the performance of marketing capabilities in environments with high and low competitiveness. The dynamism of DMC allows the responsiveness and efficiency of cross-functional business processes for creating and delivering customer value in response to market changes [

12,

19,

95], allows performance to be positive in both environments.

However, as for AMC, that is responsible for the organization’s proactive skills, the feels and acts in the face of the signals that the market transmits, constantly learning from market experiences, coordinating internal resources to respond quickly to these changes [

17,

26], acts positively on the organization’s performance when the environment is more competitive, which shows how important the organization be attentive to the market and to adapt to it [

19], and the importance of the company to detect, interpret and act on these critical signals in its international business environment, faster than competitors, leading to a significant competitive advantage [

53]. Since the DMC and AMC marketing capabilities were significant at IMP, we reaffirm the importance of understanding marketing practices [

94], especially when we are dealing with a market with such complexity and transformation, such as B2B internationally [

1,

3,

96].

6. Conclusions

Studies related to marketing skills become increasingly relevant and necessary as to the understanding of their effects on organizations [

9], especially when these capabilities are placed in an international environment [

8] in which they are justified by the complexity that the international market involves, and they raise the level of demand in organizations as to the need to develop essential capabilities that aim to increase their competitive advantage [

97,

98,

99]. It is for these reasons that over the years, it has been realized that investigations relate the results of international marketing performance to international marketing [

100,

101,

102,

103].

Supported in the literature as creating value for the organization, marketing capabilities [

104], face three difficulties, one when they are exposed to the international B2B environment, which, due to the complexities between commercial relationships, raise the need to build a brand, and studies have already pointed out the importance of building a strong brand within this context, whether through marketing skills and/or the relationships established between stakeholders [

105]. The second is related to small and medium-sized companies—SMEs, which, when starting an internationalization process, require the organization and its managers to bring together different internal capacities and resources (logistics, marketing, relational resources with suppliers, among other areas) and the need for these competencies, making internationalization complex and risky for small and medium-sized companies [

106,

107]. Third, facing a highly competitive market, may prevent the achievement of advantageous resources, opportunities, and spaces for maintaining and sustaining the business model [

1,

21,

22].

Presented in this study, it is possible to verify the importance of building increasingly adaptable marketing capabilities, capable of keeping up with market changes, technology, and competitors’ strategies. Using and enriching the dynamic and adaptive capabilities, add positively to the international performance of SMEs, especially in environments of high, competitive, intensity, combined they demonstrate the positive effects on performance. As proposed at the beginning of this study, relevant results were presented regarding the effects of the marketing capabilities on the international marketing performance. Through a theoretical foundation, this research in a practical way, bring trends and inspirations to Portuguese SMEs, and this study manages to be a source of consultation and guidance for organizations that intend to enter an international market and/or already operating in the international market, not only Portuguese but also worldwide. Within the scope of the results presented here, we also recommend the constant development of marketing capabilities, namely dynamic and adaptive, in order to build sustainable competitive advantage in international markets, mainly involving building relationships with different stakeholders, learning from the new market, and observation of competitors, to retain the knowledge necessary to take advantage of existing opportunities. Although some variables are not statistically significant in this study, they are still likely to be developed by organizations, since their composition in the marketing capacity, produces positive effects on international marketing performance. The results of our study point out that the managers of small and medium companies present in the international B2B market should seek to provide their companies with an elevated level of dynamic and adaptive marketing capabilities based on the company itself and on the market conditions. However, our results also suggest that when the competitive intensity varies the relationship of the various marketing capacities and the international marketing performance is dynamic, and points to the need to deepen the relationship between customers and the product development process, for example, through models of co-creation and the development of an open marketing system that improves the relationship between the company’s capabilities and the external environment; that is, with customers, suppliers, and the entire network of partners. Research with theoretical and current foundations, which allows leaders and marketers to use it as a daily tool in building stronger marketing capacities, which allow business sustainability in the international market, assisting in strategic decision making to promote better results in the competitive B2B market.

6.1. Limitations and Future Research Avenues

The present research also has its own limitations. First, we highlight its cross-sectional nature, which occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic, may have limited the scope of the survey and even the organizations’ own willingness to respond to the survey, somewhat extensive. Despite starting this study with a database already formed with Portuguese SMEs in the international market, the global pandemic context has led many of the database contacts to be invalid, whether due to dismissal, termination of activities, or reduced activities, such as the case of the layoff. This aspect makes it difficult to claim causality in the context of the present research. Second, it is based on a single country sample of B2B SMEs, in this case Portugal, a fact that hinders the generalization of results.

In order to overcome these limitations, other studies can be done with the inclusion of other countries in the population sample, allowing a comparison between the differences in the performance of marketing capabilities in international marketing performance. As perceived throughout this study, many paths can be followed in future investigations, through studies specific to each marketing capacity and its effects with international marketing performance; studies evaluating competitive intensity, analyzing as a moderator, between the effects of marketing capabilities and international performance [

22]. It also allows other studies to use international marketing performance from individual component analysis; likewise, it is possible to aggregate other information that may influence both the international marketing performance of the organization and the development of marketing capabilities, such as demographic and organizational management characteristics of companies, differentiating them by countries, for example. It is also possible to develop sector studies, and studies with longitudinal characteristics, as well as the inclusion of other marketing capabilities within this international market scenario.