The Role of Social Enterprise Hybrid Business Models in Inclusive Value Chain Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Inclusive Value Chain Development

2.2. Hybrid Organisations

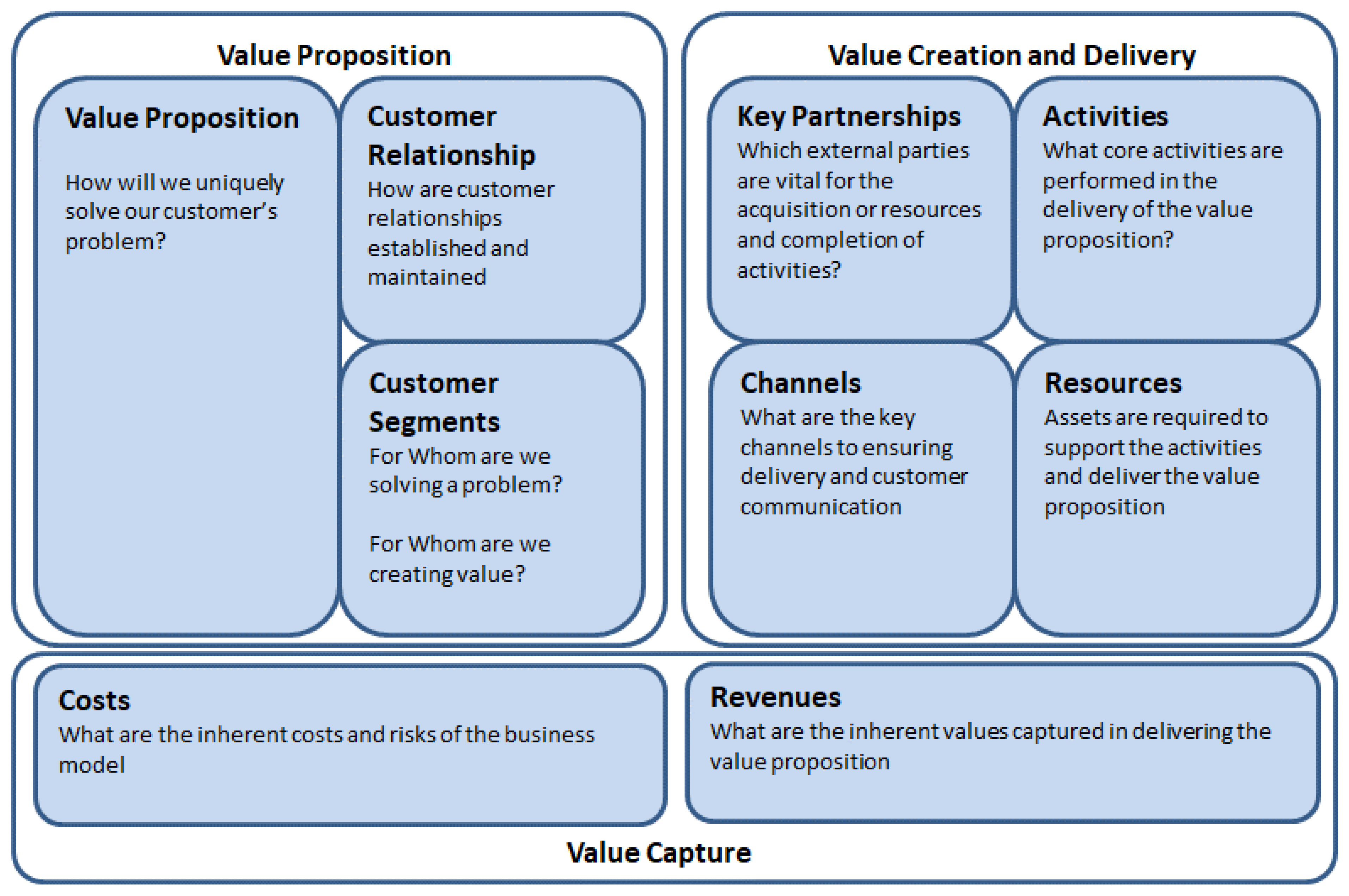

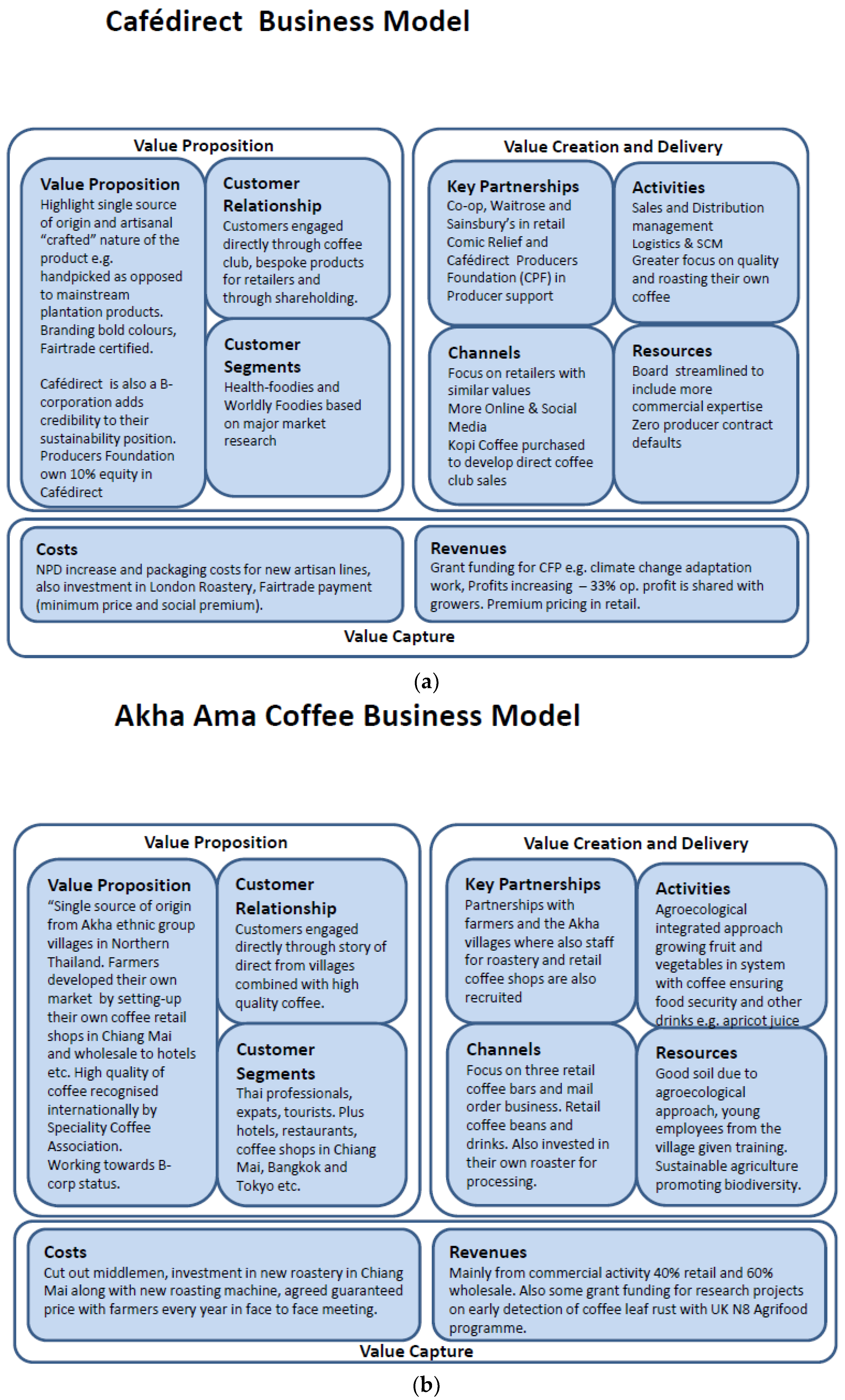

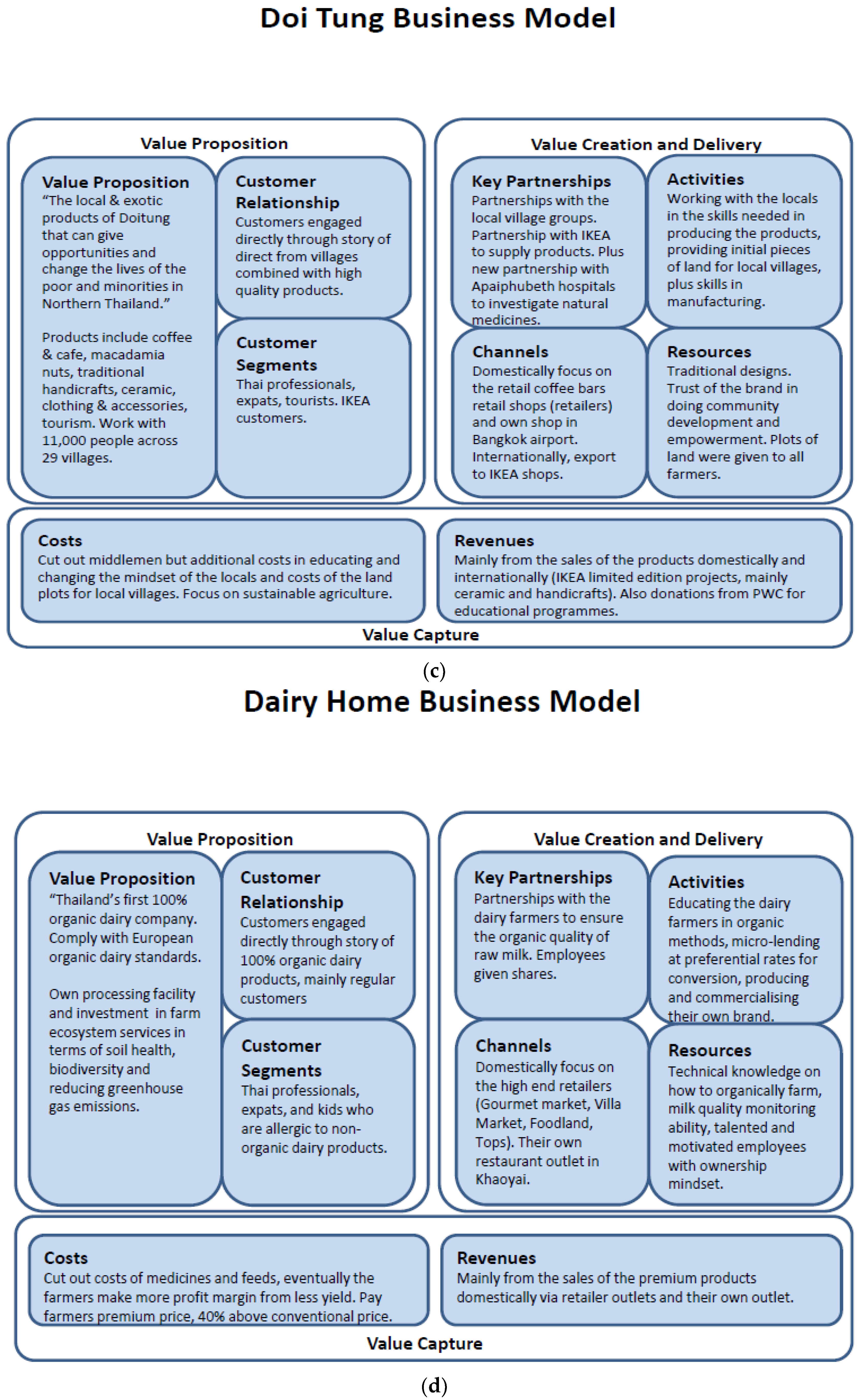

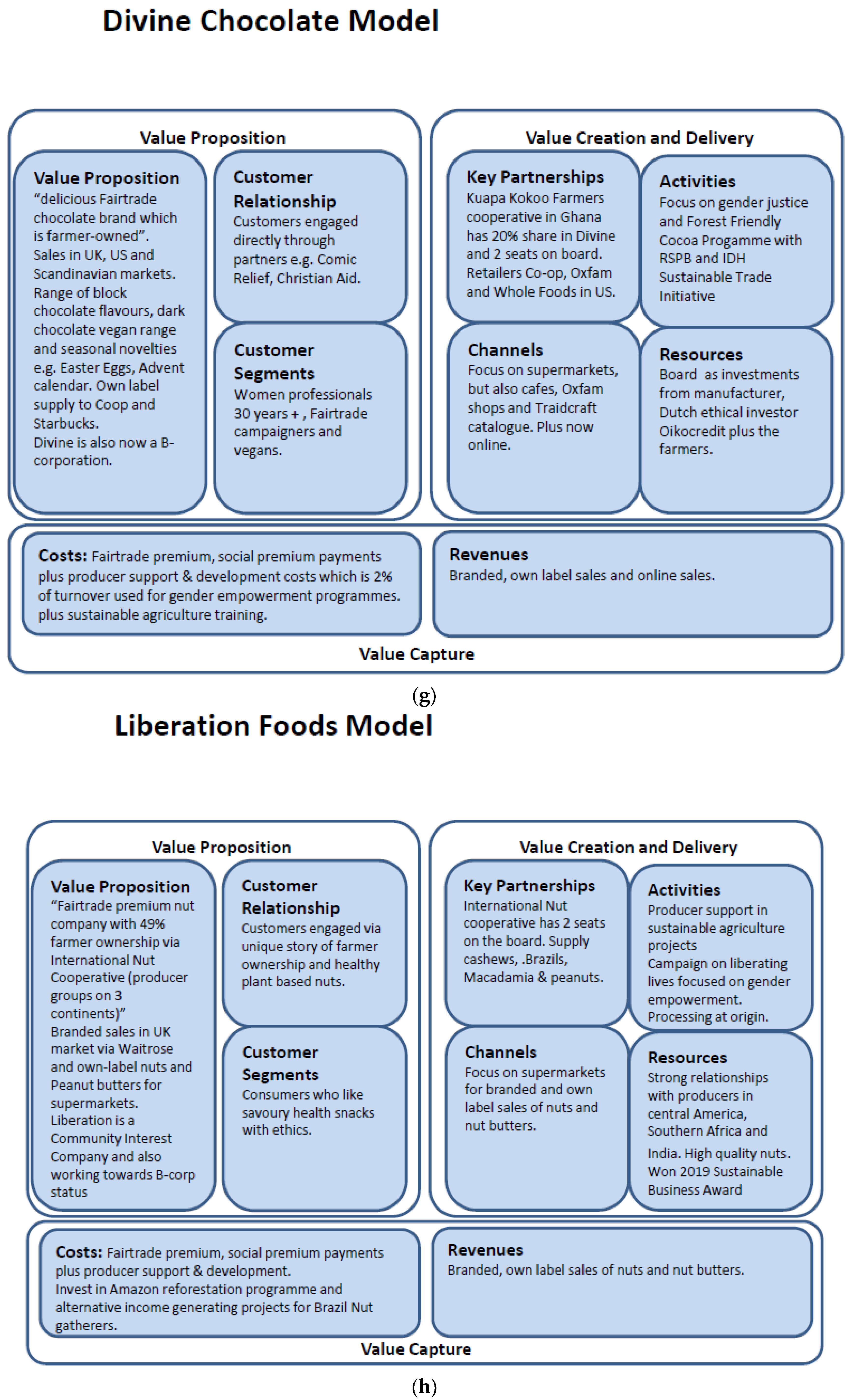

2.3. Sustainable Business Models

3. Research Objective and Context

4. Methodology

5. Data Collection

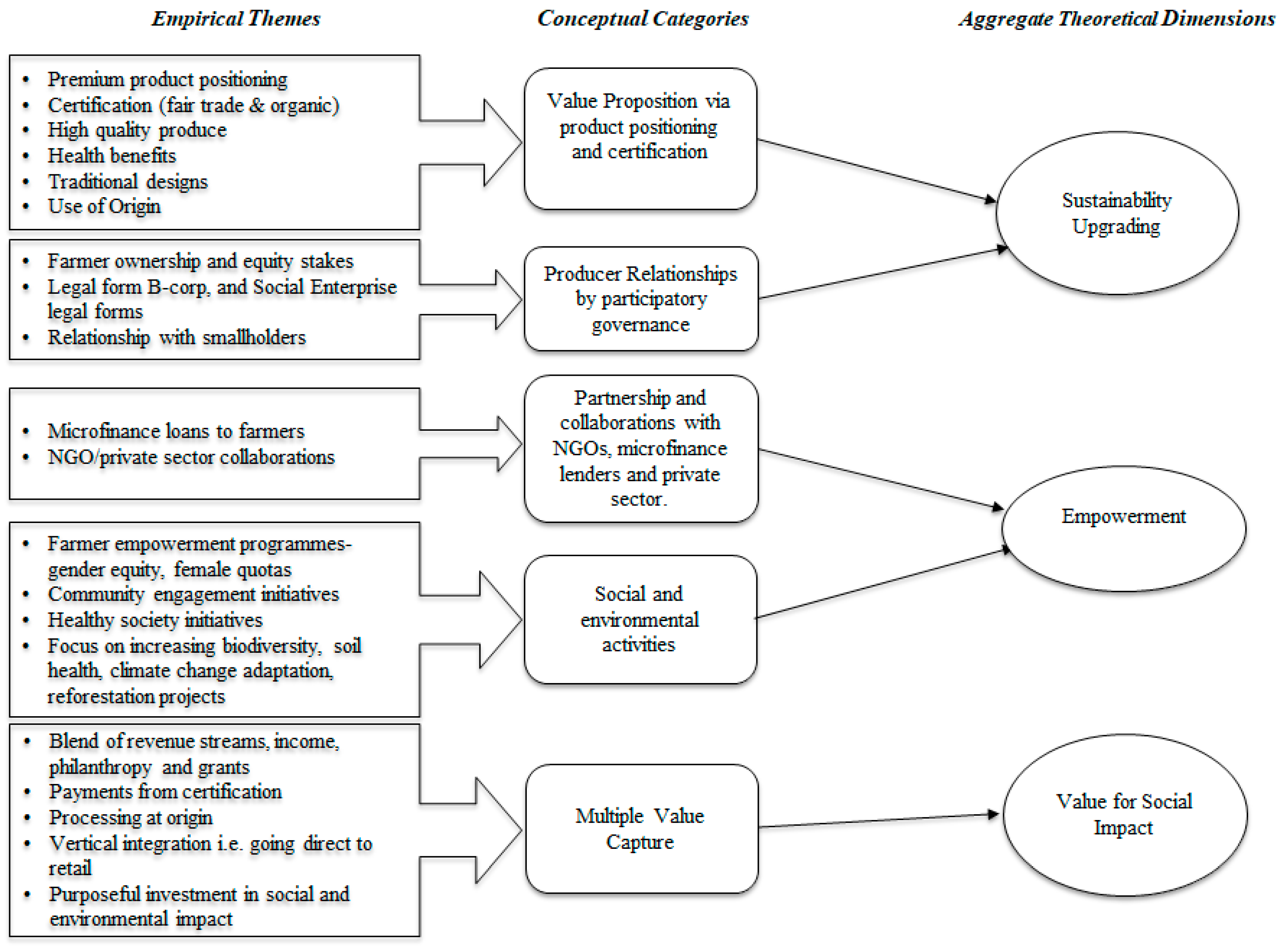

6. Data Analysis

7. Findings

7.1. Sustainability Upgrading

“Our aim is to create more value for smallholders by integrating them into the growing, roasting and retailing of their coffee.”(CEO interview, Akha Ama Coffee)

“Our peanut producers in Nicaragua are expanding their own processing facility capabilities as we speak and we’re very involved in that project, feeding through the expertise so they can build their own peanut processing plant and manufacture peanut butter at origin. We’re adding value back down the supply chain via both the fair trade premium and the social premium we pay.”(CEO interview, Liberation)

“Kuapa Kokoo farmers cooperative in Ghana have been able due to their ownership of the Divine brand to borrow money at preferential rates to invest in organisational capacity building and community infrastructure.”(Chair of Divine board interview)

7.2. Empowerment

“When our farmers were short of cash flow and they didn’t have enough credit to take loans from banks, we lent the money to them so that both their operations and ours can continue. We cannot stop our operations as there is limited amount of organic milk in the market and we are the biggest supplier. That’s our commitment to the customers and the society that we have to deliver.”(CEO and Founder interview, Dairy Home)

“We need to change the dairy farmers’ mindset that not the amount of milk they sell and the revenue matter, but the savings they received at the end of the day plus the higher premium market price. By converting their farms into organic farms, farmers receive less milk per day but higher quality of milk and less spending on cow medicines and feeds. Hence, they receive more savings as well.”(CEO and Founder interview, Dairy Home)

“I think the ownership structure and the board are important and so the fact that the board has got cocoa farmers on it to integrate the community of beneficiaries into the ownership of the organization and decision-making structures of the organization. The whole model feels like a genuine partnership”(CEO interview, Divine)

“Initially, the people here did not trust us at all; it took us a long time to prove to them that we really wanted to help them to have better lives. Then, slowly they changed from opium growing and trading to coffee growing. Then, they started to learn how to roast and make coffee as well. Eventually, they started to see improvements in health and later in wealth and better education and future for their children”(CEO interview, Doi Tung)

“A key decision at the outset in 1993 was to set quotas for women’s participation in the cooperative with at least two representatives of the village society had to be women, plus there had to be a gender balance at both regional and national executive levels. In 2010, Kuapa Kokoo for the first time a female president”(CEO interview, Divine)

“We work closely together as equal partners with our smallholders as part of the organic participatory guarantee scheme we have set-up learning schools and allowing our organic growers through regional societies a say in the future direction of Lemon Farm”(CEO interview, Lemon Farm)

“We even divided part of our lands into small pieces and gave them all to each individual household in the village to grow the coffee and manage their own farms. What they harvested from the farms, they can sell back to us at a guaranteed price or they can sell to others, we are totally OK with it because our aim is to improve their quality of life and livelihood.”(Business Development Director interview, Doi Tung)

“Even though I see some new business opportunity, I will not go for it if it does not help improving the lives of my village’s people. To grow my business, I will not go into anything that only makes profit; it also needs to be beneficial for my community and their environment. I would rather focus on my village’s people and what they are capable of, which maybe growing some fruits and vegetables. We have organised a village committee, which meets regularly to discuss any key issues with production. We also agree the annual coffee price through this committee by sharing costs of inputs etc. The leading females in the village participate actively in these discussions and often prepare the records of costs”(CEO and Founder interview, Akha Ama)

7.3. Value for Social Impact

“We sit down each February in a meeting with villages to agree the coffee price for that season. We share our respective costs, challenges and arrive at an agreement. It is often the women in the village who contribute most to these discussions and usually have prepared the evidence of costs and purchases”(CEO and Founder interview, Akha Ama Coffee).

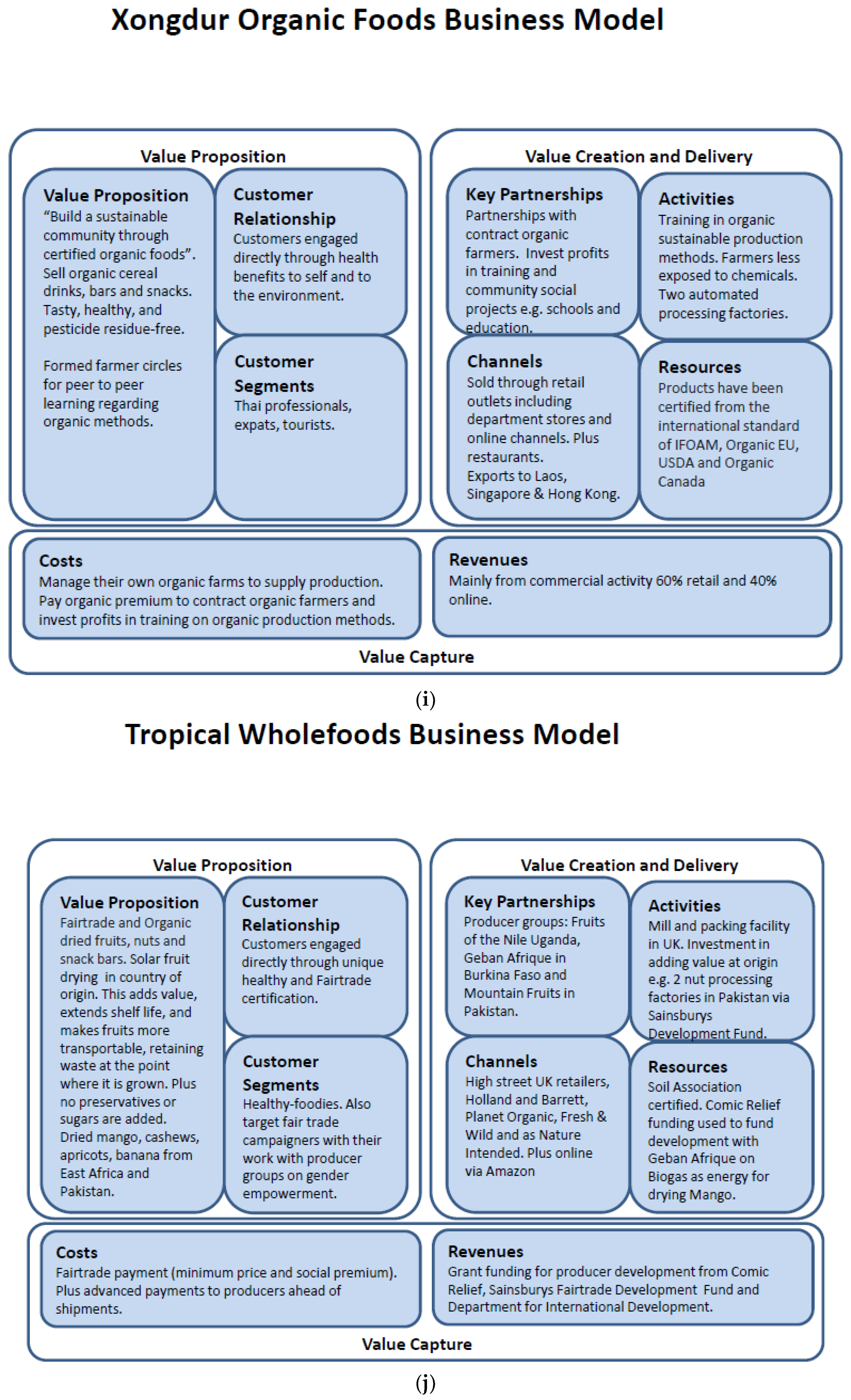

“That’s the whole point of our company; our company is here to change the way that the food industry works by aiming to improve the livelihoods of farmers. So, we would not be here at all if it wasn’t for that aim.”(Director interview, Xongdur Organic Foods)

“The mission used to be only about the livelihood of growers. It now is also about product and about business pioneering as well.”(CEO interview, Doi Tung)

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devaux, A.; Torero, M.; Donovan, J.; Horton, D. Agricultural innovation and inclusive value-chain development: A review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Franzel, S.; Cunha, M.; Gyau, A.; Mithöfer, D. Guides for value chain development: A comparative review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 5, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, A.; Donovan, J.; Stoian, D. Smallholder value chains as complex adaptive systems: A conceptual framework. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggblade, S.; Theriault, V.; Staatz, J.; Dembele, N.; Diallo, B. A Conceptual Framework for Promoting Inclusive Agricultural Value Chains. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.420.1747&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Norese, M.F.; Corazza, L.; Bruschi, F.; Cisi, M. A multiple criteria approach to map ecological-inclusive business models for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World 2020, 28, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekumhene, C.; De Vries, J.; Paassen, A.V.; Schut, M.; MacNaghten, P. Making Smallholder Value Chain Partnerships Inclusive: Exploring Digital Farm Monitoring through Farmer Friendly Smartphone Platforms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asikin, Z.; Baker, D.; Villano, R.; Daryanto, A. Business Models and Innovation in the Indonesian Smallholder Beef Value Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelo, E.; Casalegno, C.; Civera, C.; Mosca, F. Turning farmers into business partners through value co-creation projects. Insights from the coffee supply chain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Trade Forum. Routes to inclusive and sustainable trade. In International Trade Forum 4; International Trade Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfam. Ripe for Change: Ending Human Suffering in Supermarket Supply Chains; Oxfam GB for Oxfam International: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, C.; Sundstrom, W.A.; Eugenia, M.E.F.; Gomez, F.; Mendez, V.E.; Santos, R.; Goldoftas, B.; Dougherty, I. Explaining the ‘hungry farmer paradox’: Smallholders and fair-trade cooperatives navigate seasonality and change in Nicaragua’s corn and coffee markets. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 25, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangu, J.; Mangnus, E.; van Westen, A.C. Limitations of Inclusive Agribusiness in Contributing to Food and Nutrition Security in a Smallholder Community. A Case of Mango Initiative in Makueni County, Kenya. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Resilient Livelihoods—Disaster Risk Reduction for Food and Nutrition Security Framework Programme; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nature Editorial. Ending Hunger: Science must stop neglecting smallholder farmers. Nature 2020, 586, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danse, M.; Klerkx, L.; Reintjes, J.; Rabbinge, R.; Leeuwis, C. Unravelling inclusive business models for achieving food and nutrition security in BOP markets. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 24, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannothra, C.G.; Manning, S.; Haigh, N. How hybrids manage growth and social–business tensions in global supply chains: The case of impact sourcing. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Jonker, J.; Baumgartner, R.J. Going one’s own way: Drivers in developing business models for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Chambers, L. Integrating hybridity and business model theory in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Doherty, B. Balancing a hybrid business model: The search for equilibrium at Cafédirect. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 1043–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billis, D. Hybrid Organizations for the Third Sector. Challenges for Practice, Theory, and Policy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.C.; Santos, F. Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Patterson, M.; Kelly, C.; Mair, J. Organizations driving positive social change: A review and an integrative framework of change processes. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1250–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M. Confronting the coffee crisis: Can fair trade, organic, and specialty coffees reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in northern Nicaragua? World Dev. 2005, 33, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Sturgeon, T. The governance of global value chains. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2005, 12, 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.; Pohlen, T. Supply Chain metrics. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2001, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Timmer, C.P. The economics of the food system revolution. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2012, 4, 225–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, J.; Salamanca, A.; Phongsir, M.; Sripun, M. More farmers less farming? Understanding the truncated agrarian transitions in Thailand. World Dev. 2018, 107, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorringa, P.; Pegler, L. Globalisation, firm upgrading and impacts on labour. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2006, 97, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, D.; Donovan, J.; Fisk, J.; Muldoon, M. Value chain development for rural poverty reduction: A reality check and a warning. Enterp. Dev. Microfinanc. 2012, 23, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Tranchell, S. New thinking in international trade? A case study of The Day Chocolate Company. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Stoian, D.; Poe, K. Value chain development in Nicaragua: Prevailing approaches and tools used for design and implementation. Enterp. Dev. Microfinanc. 2017, 28, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minot, N.; Sawyer, B. Contract farming in developing countries: Theory, practice, and policy implications. In Innovation for Inclusive Value Chain Development: Successes and Challenges; Devaux, A., Torero, M., Donovan, J., Horton, D.E., Eds.; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 127–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffen, P. A chocolate-coated case for alternative international business models. Dev. Pract. 2002, 12, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Poole, N. Changing asset endowments and smallholder participation in higher value markets: Evidence from certified coffee producers in Nicaragua. Food Policy 2014, 44, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, S.; Duncan, A.; Larbi, A.; Khanh, T.T. Enhancing innovation in livestock value chains through networks: Lessons from fodder innovation case studies in developing countries. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, G.; Devaux, A.; Reinoso, I.; Pico, H.; Montesdeoca, F.; Pumisacho, M.; Horton, D. Multi-stakeholder platforms for linking small farmers to value chains: Evidence from the Andes. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2011, 9, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaans, K.; Cullen, B.; Van Rooyen, A.F.; Adekunle, A.; Ngwenya, H.; Lema, Z.; Nederlof, S. Dealing with critical challenges in African innovation platforms: Lessons for facilitation. Knowl. Manag. Dev. J. 2013, 9, 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Saenger, C.; Torero, M.; Qaim, M. Impact of third-party contract enforcement in agricultural markets—A field experiment in Vietnam. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 96, 1220–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi Women and Labour Market Decisions in London and Dhaka; Verso: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mosedale, S. Assessing women’s empowerment: Towards a conceptual framework. J. Int. Dev. 2005, 17, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction and delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Moss, T.W.; Gras, D.M.; Kato, S.; Amezcua, A.S. Entrepreneurial processes in social contexts: How are they different, if at all? Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Conceptions of social enterprise in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences. Soc. Enterp. J. 2006, 1, 32–53. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, S. Negotiating tensions: How do social enterprises in the homelessness field balance social and commercial considerations? Hous. Stud. 2012, 27, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Doherty, B. A fair trade-off? Paradoxes in the governance of fair-trade social enterprises. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different or both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, I.; Lyon, F. Beyond green niches? Growth strategies of environmentally-motivated social enterprises. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 32, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillett, A.; Loader, K.; Doherty, B.; Scott, J.M. An examination of tensions in a hybrid collaboration: A longitudinal study of an empty homes project. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 157, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.W.; Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, M.T. Collective social entrepreneurship: Collaboratively shaping social good. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, T.; Stoetter, N. Social Entrepreneurs as responsible leaders: ‘Fundación Paraguya’ and the case of Martin Burt. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Battilana, J.; Cardenas, J. Organizing for society: A typology of social entrepreneuring models. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, W.F.; Crittenden, V.L. Strategic planning in third-sector organizations. J. Manag. Issues 1997, 9, 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh, N.; Hoffman, A.J. Hybrid organizations. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P.; McElwee, G. Situating community enterprise: A theoretical explanation. Entrep. Region. Dev. 2011, 23, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, E. The categorical imperative: Securities analysts and the illegitimacy discount. Am. J. Sociol. 1999, 104, 1398–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, H.B. The role of non-profit enterprise. Yale Law J. 1980, 89, 835–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing research on hybrid organizing. Insights from the study of social enterprises. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G.; Elias, J. The challenges of combining social and commercial enterprise. Bus. Ethics Q. 1998, 8, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F.; Pache, A.C.; Birkholz, C. Making hybrids work: Aligning business models and organizational design for social enterprises. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2015, 57, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Tracey, P. Institutional complexity and paradox theory: Complementarities of competing demands. Strateg. Organ. 2016, 14, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wry, T.; Zhao, E.Y. Taking Trade-offs Seriously: Examining the Contextually Contingent Relationship Between Social Outreach Intensity and Financial Sustainability in Global Microfinance. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Margiono, A.; Zolin, R.; Chang, A. A typology of social venture business model configurations. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 626–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J. The business model: An integrative framework for strategy execution. Strateg. Chang. 2008, 17, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, C.L.; Broman, G.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Basile, G.; Trygg, L. An approach to business model innovation and design for strategic sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 140, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. Design thinking to enhance the sustainable business modelling process—A workshop based on a value mapping process. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upward, A.; Jones, P. An Ontology for Strongly Sustainable Business Models Defining an Enterprise Framework Compatible with Natural and Social Science. Organ. Environ. 2015, 29, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paroutis, S.; Heracleous, L. Discourse revisited: Dimensions and employment of first order discourse during institutional adoption. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 935–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, C. Case research in operations management. In Researching Operations Management; Karlsson, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 176–209. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Kittipanya-Ngam, P. The Emergence and Contested Growth of Social Enterprise in Thailand. J. Asian Public Policy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, R.M.; Thankappan, S.; Doherty, B. Agricultural and food systems in the Mekong region: Drivers of transformation and pathways of change. Emerald Open Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.M. An analysis of the grounded theory method and the concept of culture. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askey, H.; Knight, P. Interviewing for Social Scientists; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and interpretation of qualitative data in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C. Better Business: How the B Corp Movement Is Remaking Capitalism; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B. Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment through Fair Trade Social Enterprise: Case of Divine Chocolate and Kuapa Kokoo. In Entrepreneurship and the Sustainable Development Goals Vol: 8; Apostolopoulos, N., Al-Dajani, H., Holt, D., Jones, P., Newbury, R., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2018; Chapter 9; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, C.; Bek, D. (Re)politicising empowerment: Lessons from the South African wine industry. Geoforum 2006, 37, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rowlands, J. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Siim, B. Introduction: The politics of inclusion and empowerment: Gender class and citizenship. In The Politics of Inclusion and Empowerment: Gender, Class and Citizenship; Anderson, J., Siim, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004; Chapter 1; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Said-Allsopp, M.; Tallontire, A. Pathways to empowerment? Dynamics of women’s participation in Global Value Chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilelu, C.W.; Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C. Supporting smallholder commercialisation by enhancing integrated coordination in agrifood value chains: Experiences with dairy hubs in Kenya. Exp. Agric. 2017, 53, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G. The Organization of Buyer-Driven Global Commodity Chains: How, U.S. Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks. In Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism; Gereffi, G., Korzeniewicz, M., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 1994; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Organisation and Mission | Market Sector and Year Founded | Interviewees | Secondary Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Akha Ama Coffee Mission: “Improve the livelihood of and to strengthen the people of the village sustainably and organically though coffee and local produces” | Coffee Founded 2007 | Founder and CEO (2) | Newspaper articles, company’s public interviews and articles, leaflets |

| B | Cafédirect Mission: “We champion the work and passion of smallholder growers, delivering great tasting hot drinks to improve livelihoods, whilst pioneering new & better ways to do business.” | Coffee, tea and cocoa Founded 1991 | CEO (1) Commercial Manager (1) Producer Organisation leader (1) | Annual reports, shareholder reports, newspaper articles, Gold Standard Impact Report, Cafédirect Producer Direct Charity Report |

| C | Dairy Home Mission: “Improve the health of people, workforce, and the community through organic dairy products” | Organic dairy products including ice cream, yoghurt, fresh milk, milk tablets, butter and bakery Founded as social enterprise in 2018 | CEO (1) Business Development Director (1) | Newspaper articles, company’s public interviews and websites, leaflets |

| D | Divine Mission: “Improve the livelihoods of cocoa farmers by putting them higher up the value chain.” | Cocoa confectionery Founded 1998 | CEO (1) Manager (1) | Annual reports, newspaper articles, board meeting minutes |

| E | Doi Tung Mission: “Solve the poverty and lack of opportunity of the people of Doitung through human, environmental, and economic development” | Coffee, macadamia nuts, handicraft and tourism Founded 1988 | CEO (1) Business Development Director (1) | Annual reports, financial reports, leaflets, books, newspaper articles, company’s public interviews and websites, company’s clips |

| F | Lemon Farm: Mission: “Create good and organic foods for better health of everyone” | Organic food retailer in Bangkok, Thailand Founded 1999 | General Manager (1) Supply chain manager (1) | Leaflets, newspaper articles, company’s public interviews and websites |

| H | Liberation Nuts Mission: “To improve the livelihoods of small holder nut producers, we do that by growing the brand.” | Nuts (cashews, ground nuts) Founded 2007 | CEO (1) Board Director (1) Producer Group leader (1) | Annual reports, impact reports, board minutes |

| I | Siam Organic Mission: “solves the problem of farmer poverty through innovative organic products with global appeal” | Organic rice, organic pasta, organic tea bags Founded 2011 | Managing Director (1) Business Development Director (1) | * SROI report, B Corp report, annual report, newspaper articles, company’s public interviews and websites |

| J | Tropical Wholefoods Mission: “the home of Fairtrade and Organic dried fruits, nuts and snack bars. We pay fair prices in advance, develop and market farmers’ products, run our own UK factory and share useful technology and experience with our overseas partners. | Dried tropical fruit and cereal bars Founded 1998 | CEO (1) and supply chain manager (1) | Annual reports, newspaper articles |

| K | Xongdur Thai Organic Foods Mission: “Improve the health and strength of the community to be locally sustainable through organic foods—Good foods are the best medicine” | Organic cereal bars and cereal drinks, organic flour- and rice-based products Founded 2000 | Founder and Managing Director (2) | Newspaper articles, company’s public interviews and websites, leaflets |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doherty, B.; Kittipanya-Ngam, P. The Role of Social Enterprise Hybrid Business Models in Inclusive Value Chain Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020499

Doherty B, Kittipanya-Ngam P. The Role of Social Enterprise Hybrid Business Models in Inclusive Value Chain Development. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020499

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoherty, Bob, and Pichawadee Kittipanya-Ngam. 2021. "The Role of Social Enterprise Hybrid Business Models in Inclusive Value Chain Development" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020499

APA StyleDoherty, B., & Kittipanya-Ngam, P. (2021). The Role of Social Enterprise Hybrid Business Models in Inclusive Value Chain Development. Sustainability, 13(2), 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020499