Disentangling the Diversity of Forest Care Initiatives: A Novel Research Framework Applied to the Italian Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives

- (1)

- To develop a comprehensive definition for forest care initiatives;

- (2)

- To collect and systematize information through the development of an inventory of forest care initiatives in Italy;

- (3)

- To propose a scheme to catch the diversity and characterize the wealth of existing initiatives.

1.2. Scope and Definition

2. Materials and Methods

- General description and location. Regions were identified according to Eurostat NUTS 2 classification, and codes of territorial units retrieved from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT)) were used for the geographic references of the initiatives (https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/6789). For the identification of the rural areas, we referred to the national classification adopted by the National Strategy Plan (NSP) for Rural Development at the NUTS 3 level (https://www.reterurale.it/areerurali), which distinguishes among zones A (i.e., urban areas), B (i.e., rural areas with intensive agriculture), C (i.e., intermediate rural areas) and D (i.e., rural areas with overall development problems):

- Contributions to public health, and activities and services supported. Contributions to public health were distinguished into physiological, psychological, and social, as presented in [6], assessed subjectively by interpreting the manifested aims and objectives of the FCIs or by eliciting the FCIs’ managers when not clear otherwise. Activities and practices supported by the ecosystem through the initiative were inspired by Fish et al. [76], with the definition of CES and its framework developed by Scottish Natural Heritage [77] and then refined based on the FCIs’ peculiarities;

- Target users and experience in the forest. Targets were categorized as (1) the general public, (2) specific, when referring to a homogeneous cluster of a population (e.g., children, the elderly, and immigrants), and (3) people with special needs (e.g., disabled or ill people). Experiences were distinguished into (1) self-leading without the need of a guide, (2) assisted, with the presence of a guide or practitioner, and (3) experiences effective both with and without a guide;

- Hosting natural area. Hosting natural areas were divided into forests, other wooded land as defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization [78], planted forests, parks intended as public spaces designated for recreational purposes with the presence of trees, and mixed ecosystems (e.g., forests, grasslands, and shrublands), together with not better specified areas. Data for all identified FCIs had been georeferenced, and a Q-GIS point vector (shapefile) was developed. By overlapping this with the 2018 Corine Land Cover data retrieved from the Copernicus database (www.copermnicus.eu), it was possible to associate FCIs to the corresponding (broad) forest categories (i.e., broadleaf, coniferous, or mixed forests);

- Managing organization. We categorized the typologies of management organizations (i.e., as private (nonprofit or for business), public, or public–private), the main typology of the actors involved in the management of the FCI, and the temporal scale of the initiative, whether permanent, on a seasonal basis, or an event or project with a definite lifespan.

Setting the Scene of the Case Study

3. Results

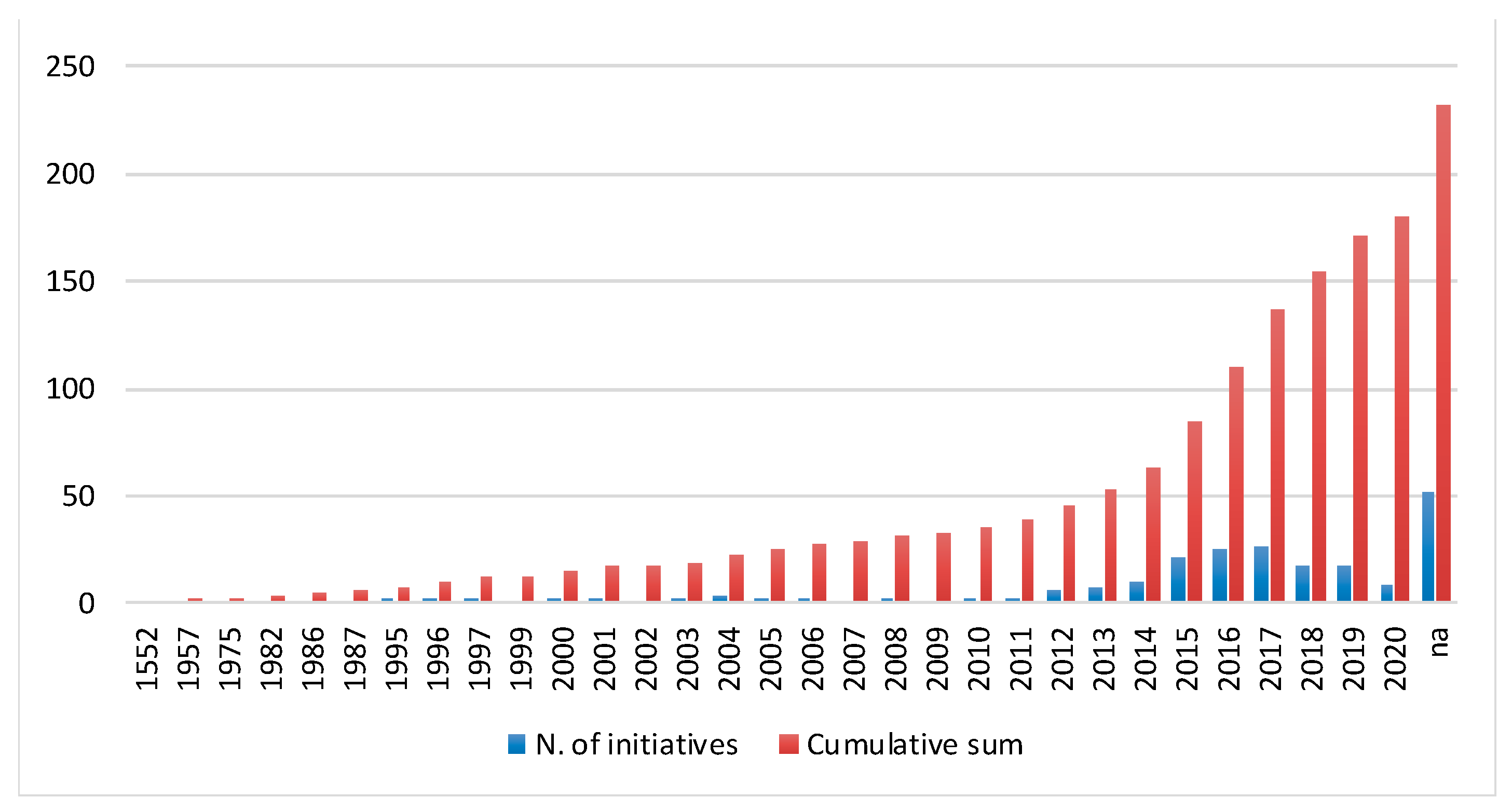

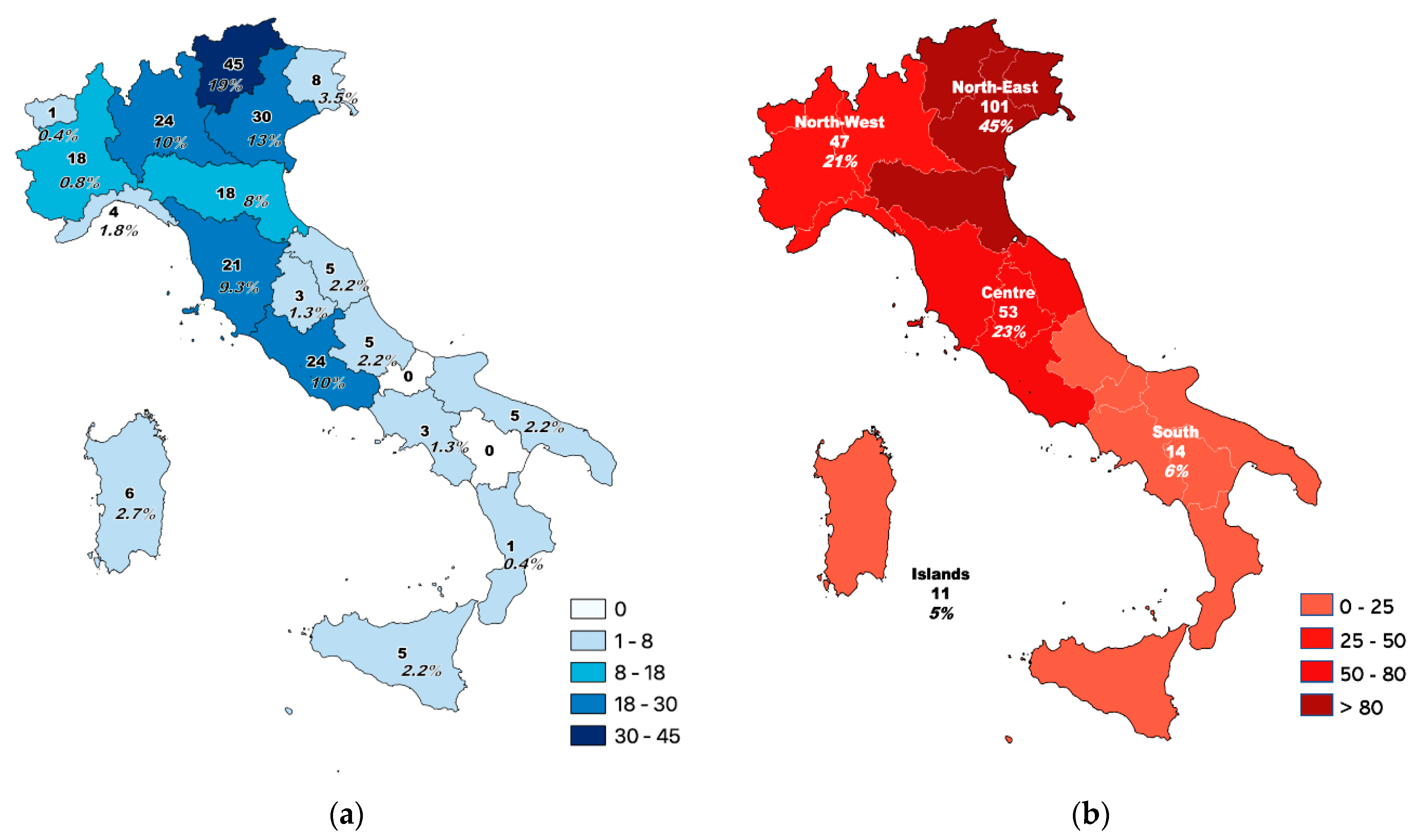

3.1. General Description of FCIs Characteristics

4. Discussion

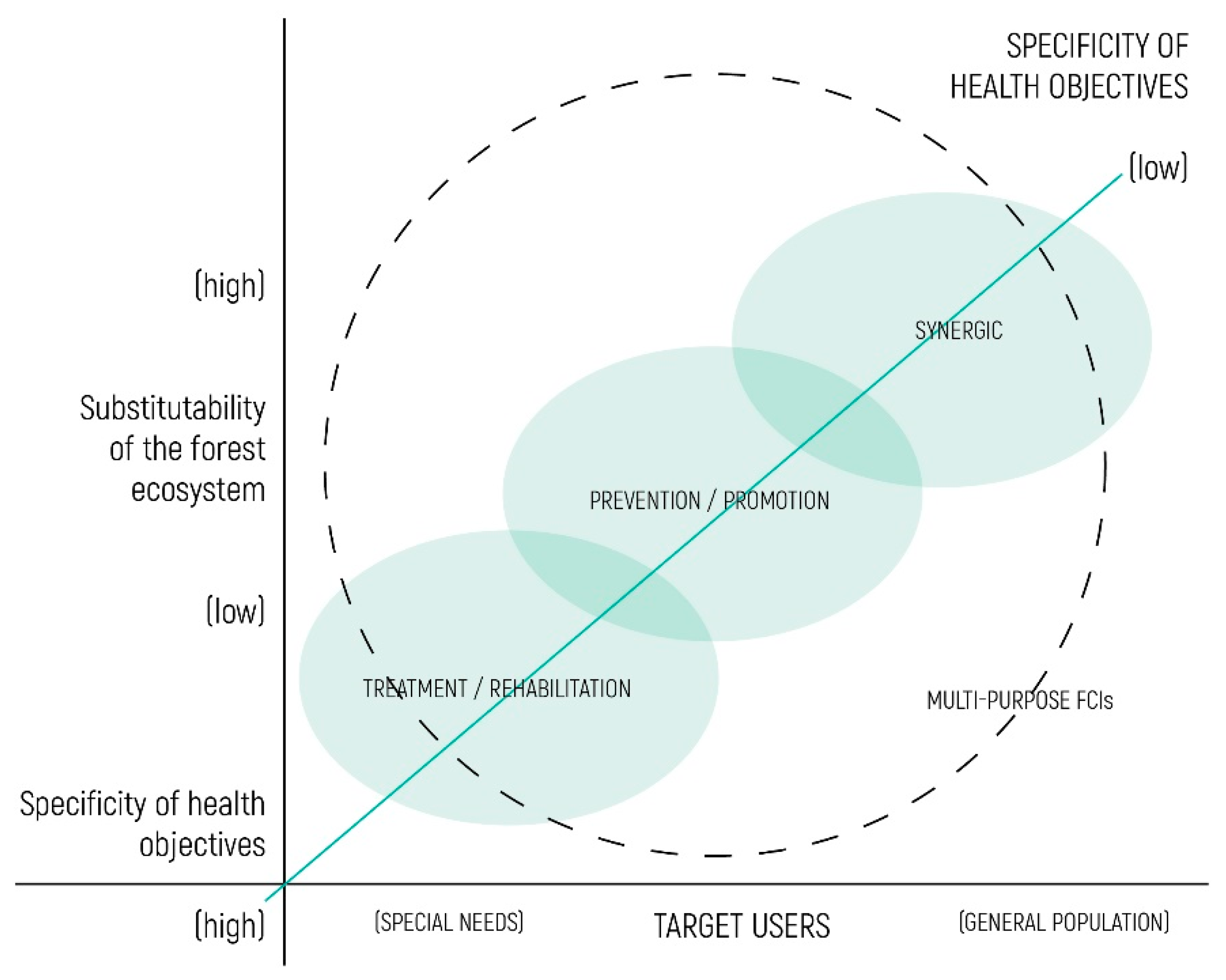

4.1. FCIs Characterization into Typologies

4.2. General Description and Location

4.3. Contributions, Effects, and Activities and Practices Supported

4.4. Target Users and Experience in the Forest

4.5. Hosting Natural Area

4.6. FCIs Categorization Scheme

4.7. Strength and Limits

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Committee and the Committee of the Regions EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 Bringing Nature Back into our Lives. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Haluza, D.; Schönbauer, R.; Cervinka, R. Green perspectives for public health: A narrative review on the physiological effects of experiencing outdoor nature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 5445–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bosch, M. Ode Sang Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health—A systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-yoku (Forest bathing) and nature therapy: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doimo, I.; Masiero, M.; Gatto, P. Forest and Wellbeing: Bridging Medical and Forest Research for Effective Forest-Based Initiatives. Forests 2020, 11, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Yeon, P.S.; Shin, W.S. The influence of indirect nature experience on human system. For. Sci. Technol. 2018, 14, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Elucidation of the physiological adjustment effect of forest therapy. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2014, 69, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, J.-C.; Dinh, T.-V.; Oh, H.-K.; Son, Y.-S.; Ahn, J.-W.; Song, K.-Y.; Choi, I.-Y.; Park, C.-R.; Suzlejko, J.; Kim, K.-H. The Potential Benefits of Therapeutic Treatment Using Gaseous Terpenes at Ambient Low Levels. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of viewing forest landscapes in a seated position in one-day forest therapy experimental model. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2014, 69, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of forest-related visual, olfactory, and combined stimuli on humans: An additive combined effect. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of visual stimulation with forest imagery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielinis, E.; Jaroszewska, A.; Łukowski, A.; Takayama, N. The effects of a forest therapy programme on mental hospital patients with affective and psychotic disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrow, M.R.; Washburn, K. A Review of Field Experiments on the Effect of Forest Bathing on Anxiety and Heart Rate Variability. Glob. Adv. Heal. Med. 2019, 8, 216495611984865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Wei, H.; He, X.; Ren, Z.; An, B. The tree-species-specific effect of forest bathing on perceived anxiety alleviation of young-adults in urban forests. Ann. For. Res. 2017, 60, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S.; Yeoun, P.S.; Yoo, R.W.; Shin, C.S. Forest experience and psychological health benefits: The state of the art and future prospect in Korea. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, N.; Korpela, K.; Lee, J.; Morikawa, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Li, Q.; Tyrväinen, L.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kagawa, T. Emotional, restorative and vitalizing effects of forest and urban environments at four sites in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7207–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, M.H.; Chang, M.C.; Lee, S.-J. The effects of forest therapy on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic stroke. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Evaluating the relaxation effects of emerging forest-therapy tourism: A multidisciplinary approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, D.; Kim, G.; Choi, Y.; Lim, H.; Park, S.; Woo, J.-M.; Park, B.-J. The prefrontal cortex activity and psychological effects of viewing forest landscapes in Autumn season. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7235–7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Joung, D.; Ikei, H.; Igarashi, M.; Aga, M.; Park, B.J.; Miwa, M.; Takagaki, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of walking on young males in urban parks in winter. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2013, 32, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, N.; Brady, E.; Steen, H.; Bryce, R. Aesthetic and spiritual values of ecosystems: Recognising the ontological and axiological plurality of cultural ecosystem “services”. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 21, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P.; Hariri, S.; Abbasi, B.; Heshmat, R.; Qorbani, M.; Motlagh, M.E.; Basagaña, X.; Kelishadi, R. Use of green spaces, self-satisfaction and social contacts in adolescents: A population-based CASPIAN-V study. Environ. Res. 2019, 168, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, L.; Morris, J.; Stewart, A. Engaging with peri-urban woodlands in England: The contribution to people’s health and well-being and implications for future management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6171–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, E. Social and Cultural Values of Trees and Woodlands in Northwest and Southeast England. For. Snow Landsc. Res. 2005, 79, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, M.; Barnes, M.; Jordan, C. Do experiences with nature promote learning? Converging evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 Diseases and Injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervinka, R.; Höltge, J.; Pirgie, L.; Schwab, M.; Sudkamp, J.; Haluza, D.; Arnberger, A.; Eder, R.; Ebenberger, M.; Lackner, C.; et al. Green Public Health—Benefits of Woodlands on Human Health and Well-Being; Bundesforschungszentrum für Wald (BFW): Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, R.; Peacock, J.; Pretty, J. Care Farming in the UK: Evidence and Opportunities Care Farming in the UK—Evidence and Opportunities Report for the National Care Farming Initiative (UK). Report for National Care Farming Institute (UK). 2008. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Care-farming-in-the-UK%3A-Evidence-and-Opportunities-Hine-Peacock/9de122ad711dbddfa2c6201b8de00393d3f5040c (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Andkjær, S.; Arvidsen, J. Places for active outdoor recreation—a scoping review. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 12, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, G.A. The “Wellness” Phenomenon: Implications for Global Agri-Food Systems. In Food Security, Nutrition and Sustainability; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2010; pp. 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, J.; Bock, B.B.; De Krom, M.P.M.M. Investigating the limits of multifunctional agriculture as the dominant frame for Green Care in agriculture in Flanders and the Netherlands. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, Responses and Experiences in Rural Restructuring—Michael Woods—Google Libri; SAGE: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubbage, F.; Harou, P.; Sills, E. Policy instruments to enhance multi-functional forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marušáková, Ľ.; Sallmannshofer, M. Human Health and Sustainable Forest Management; Marusakova, L., Sallmannshofer, M., Eds.; FOREST EUROPE—Liaison Unit Bratislava: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2019; ISBN 978-80-8093-266-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hassink, J.; van Dijk, M. Farming for Health across Europe: Comparison between countries, and recommendations for a research and policy agenda. In Farming for Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Di Iacovo, F.; O’Connor, D. Supporting policies for Social Farming in Europe Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas; ARSIA: Firenze, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-8295-107-8. [Google Scholar]

- Haubenhofer, D.K.; Elings, M.; Hassink, J.; Hine, R.E.; Menv, B. The development of green care in western european countries. Explore 2010, 6, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, C.D.; Collado, S. Experiences in nature and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Setting the ground for future research. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, A. How is high school greenness related to students’ restoration and health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, M.; Schraml, U. Understanding the role of urban forests for migrants—uses, perception and integrative potential. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S.; Goodenough, A. What is different about Forest School? Creating a space for an alternative pedagogy in England. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2018, 21, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscieme, L. Cultural ecosystem services: The inspirational value of ecosystems in popular music. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 16, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayden, A.; Green, T.; Hockey, J.; Powell, M. Cutting the lawn—Natural burial and its contribution to the delivery of ecosystem services in urban cemeteries. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.D.; Balvanera, P.; Klain, S.; Satterfield, T.; Basurto, X.; Bostrom, A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Gould, R.; Halpern, B.S.; et al. Where are Cultural and Social in Ecosystem Services? A Framework for Constructive Engagement. Bioscience 2012, 62, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirons, M.; Comberti, C.; Dunford, R. Valuing Cultural Ecosystem Services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 545–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, K.; Hutchinson, S.; Moore, T.; Hutchinson, J.M.S. Analysis of publication trends in ecosystem services research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 25, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach Pagès, A.; Peñuelas, J.; Clarà, J.; Llusià, J.; Campillo i López, F.; Maneja, R. How Should Forests Be Characterized in Regard to Human Health? Evidence from Existing Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, E.; Imai, M.; Okawa, M.; Miyaura, T.; Miyazaki, S. A before and after comparison of the effects of forest walking on the sleep of a community-based sample of people with sleep complaints. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2011, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Pousa, S.; Bassets Pagès, G.; Monserrat-Vila, S.; de Gracia Blanco, M.; Hidalgo Colomé, J.; Garre-Olmo, J. Sense of Well-Being in Patients with Fibromyalgia: Aerobic Exercise Program in a Mature Forest-A Pilot Study. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 614783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Choi, H.; Bang, K.-S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.K.; Lee, B. Effects of forest therapy on depressive symptoms among adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S.; Shin, C.S.; Yeoun, P.S. The influence of forest therapy camp on depression in alcoholics. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2012, 17, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-W.; Choi, H.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Yoon, C.-H.; Woo, J.-M.; Kim, W. The effects of forest therapy on coping with chronic widespread pain: Physiological and psychological differences between participants in a forest therapy program and a control group. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Xing, W.; Ren, X.; Lv, X.; Dong, J.; et al. The salutary influence of forest bathing on elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Jeong, H.; Park, S.; Lee, S. Forest adjuvant anti-cancer therapy to enhance natural cytotoxicity in urban women with breast cancer: A preliminary prospective interventional study. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 7, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; Li, Y.J.; Wakayama, Y.; et al. A forest bathing trip increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins in female subjects. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2008, 22, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Nakadai, A.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Shimizu, T.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; et al. Forest bathing enhances human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2007, 20, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Nakadai, A.; Matsushima, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Krensky, A.; Kawada, T.; Morimoto, K. Phytoncides (wood essential oils) induce human natural killer cell activity. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2006, 28, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.; O’Brien, E. Encouraging healthy outdoor activity amongst under-represented groups: An evaluation of the Active England woodland projects. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, K.S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.K.; Kang, K.I.; Jeong, Y. The effects of a health promotion program using urban forests and nursing student mentors on the perceived and psychological health of elementary school children in vulnerable populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, M.; Cormack, A.; McRobert, L.; Underhill, R. 30 days wild: Development and evaluation of a large-scale nature engagement campaign to improve well-being. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, N.; Morikawa, T.; Bielinis, E. Relation between psychological restorativeness and lifestyle, quality of life, resilience, and stress-coping in forest settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, S. Becoming human again’: Exploring connections between nature and recovery from stress and post-traumatic distress. Work 2015, 50, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, D.V.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Djernis, D.; Sidenius, U. ‘Everything just seems much more right in nature’: How veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder experience nature-based activities in a forest therapy garden. Health Psychol. Open 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachinger, M.; Rau, H. Forest-Based Health Tourism as a Tool for Promoting Sustainability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, J.; Woo, J.-M.; Kim, W.; Lim, S.-K.; Chung, E.-J. The effect of cognitive behavior therapy-based “forest therapy” program on blood pressure, salivary cortisol level, and quality of life in elderly hypertensive patients. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2012, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.H.; Shin, W.S.; Khil, T.G.; Kim, D.J. Six-step model of nature-based therapy process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujcic, M.; Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J.; Grbic, M.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Vukovic, O.; Toskovic, O. Nature based solution for improving mental health and well-being in urban areas. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; Pryor, A.; Brown, P.; St Leger, L. Healthy nature healthy people: “contact with nature” as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forest Therapy Society. Available online: https://www.fo-society.jp/en/index.html (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Kondo, M.C.; Oyekanmi, K.O.; Gibson, A.; South, E.C.; Bocarro, J.; HipNp, J.A. Mature prescriptions for health: A review of evidence and research opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavell, M.A.; Leiferman, J.A.; Gascon, M.; Braddick, F.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Litt, J.S. Nature-Based Social Prescribing in Urban Settings to Improve Social Connectedness and Mental Well-being: A Review. Curr. Environ. Health Reports 2019, 6, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, E.; Sarjala, T.; Raitio, H. Promoting human health through forests: Overview and major challenges. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2009, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattler, C.; Matzdorf, B. PES in a nutshell: From definitions and origins to PES in practice-Approaches, design process and innovative aspects. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Willis, C.; Winter, M.; Tratalos, J.A.; Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Making space for cultural ecosystem services: Insights from a study of the UK nature improvement initiative. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawcliffe, P. Cultural Ecosystem Services—Towards a Common Framework for Developing Policy and Practice in Scotland. Available online: https://www.nature.scot/sites/default/files/2017-06/Cultural%20ecosystem%20Services%20-%20towards%20a%20common%20framework%20for%20developing%20policy%20and%20practice%20in%20Scotland%20-%20Working%20Paper%20-%20October%202015%20-%20final%20for%20web%20(February%202016).pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- FAO. The Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015 Terms and Definitions; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, K.J.; Perry, E.E.; Thom, D.; Gladkikh, T.M.; Keeton, W.S.; Clark, P.W.; Tursini, R.E.; Wallin, K.F. The woods around the ivory tower: A systematic review examining the value and relevance of school forests in the United States. Sustainability 2020, 12, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.B.; Strauss, A.L. The discovery of Grounded theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research; AldineTransaction: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1967; Volume 66–28314, ISBN 0-202-30260-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rete Rurale Nazionale. Rapporto Annuale sul Settore Forestale; Compagnia delle Foreste: Arezzo, Italy, 2019; ISBN 9788898850341. [Google Scholar]

- INFC Secondo Inventario Nazionale (INFC2005). Available online: https://www.sian.it/inventarioforestale/jsp/dati_introa.jsp?menu=3 (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Secco, L.; Pettenella, D.; Gatto, P. Forestry governance and collective learning process in Italy: Likelihood or utopia? For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, L.; Paletto, A.; Romano, R.; Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D.; Carbone, F.; De Meo, I. Orchestrating forest policy in Italy: Mission impossible? Forests 2018, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE, United Nations. Green Jobs in the Forest Sector. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/timber/publications/DP71_WEB.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Barnes, M.R.; Donahue, M.L.; Keeler, B.L.; Shorb, C.M.; Mohtadi, T.Z.; Shelby, L.J. Characterizing Nature and Participant Experience in Studies of Nature Exposure for Positive Mental Health: An Integrative Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascaroli, F.; Zannini, P.; Teresa, A.; Acosta, R.; Chiarucci, A.; Nascimbene, J. Sacred natural sites in Italy have landscape characteristics complementary to protected areas: Implications for policy and planning. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 113, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, H.; Balian, E.; Azevedo, M.N.; Beumer, V.; Brodin, T.; Claudet, J.; Fady, B.; Grube, M.; Keune, H.; Lamarque, P.; et al. Nature-based Solutions: New Influence for Environmental Management and Research in Europe Nature-based Solutions: New Influence for Environmental Management and Research in Europe | GAIA 24/4 (2015): 243-248 Nature-based Solutions, an Emerging Term. Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2015, 24, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Byg, A.; Hartel, T.; Hurley, P.; Sar, C.; Ló Pez-Santiago, A.; Nagabhatla, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; et al. The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naomi, A.S. Access to Nature Has Always Been Important; With COVID-19, It Is Essential. Heal. Environ. Res. Des. J. 2020, 13, 242–244. [Google Scholar]

| General Description and Location | Dimension | Indicators | n. | % |

| Status | Active | 181 | 78.02 | |

| Pilot | 1 | 0.43 | ||

| Design Phase | 5 | 2.16 | ||

| Abandoned | 16 | 6.9 | ||

| Unknown | 29 | 12.5 | ||

| Scale of action | Local | 190 | 81.9 | |

| Regional | 35 | 15.09 | ||

| National | 6 | 2.59 | ||

| International | 1 | 0.43 | ||

| PSN rural class | A | 67 | 28.87 | |

| B | 38 | 16.37 | ||

| C | 40 | 17.24 | ||

| D | 78 | 33.62 | ||

| NA (Not Applicable) | 9 | 3.87 | ||

| Type of Initiative | Permanent | 130 | 56.03 | |

| Seasonal | 46 | 19.83 | ||

| Event or Project | 43 | 18.53 | ||

| Network or Research | 9 | 3.88 | ||

| NA | 4 | 1.72 | ||

| Contribution to Health and Activities and Services Supported | Contributions to health ** | Physiological | 68 | 29.31 |

| Psychological | 86 | 37.07 | ||

| Social | 183 | 78.88 | ||

| Activities and services supported by FCIs ** | Sport | 42 | 18.1 | |

| Recreation and Tourism | 96 | 41.38 | ||

| Adventure and Wilderness | 106 | 45.69 | ||

| Psychophysical Therapy or Rehabilitation | 29 | 12.5 | ||

| Wellness and Relaxation | 74 | 31.9 | ||

| Spirituality | 24 | 10.34 | ||

| Social Cohesion | 47 | 20.26 | ||

| Social Inclusion (Social Care) | 28 | 12.07 | ||

| Inspiration (Artistic or Cultural) | 63 | 27.16 | ||

| Learn from Nature | 118 | 50.86 | ||

| Livelihood Provision and Income diversification | 13 | 5.6 | ||

| FCIs with Multiple Contributions | 219 | 93 | ||

| Target Users and Experience in the Forest | Target Users | General Public | 98 | 42.24 |

| Specific Target | 107 | 46.12 | ||

| Special Needs | 25 | 10.78 | ||

| Mixed or Not Specified | 2 | 0.86 | ||

| User’s experience | Self-Leading | 40 | 17.24 | |

| Assisted | 159 | 68.53 | ||

| Both | 28 | 12.07 | ||

| NA | 5 | 2.16 | ||

| Hosting Natural Area | Hosting Area | Fixed (One) | 124 | 53.45 |

| Fixed (More Than One) | 12 | 5.17 | ||

| Itinerant | 65 | 28.02 | ||

| NA | 31 | 13.36 | ||

| Ecosystem | Forest or Woodland | 96 | 41.38 | |

| Park | 19 | 8.19 | ||

| Planted | 10 | 4.31 | ||

| Mixed or Unspecified | 107 | 46.12 | ||

| Forest Type * | Bradleaved | 65 | 28.63 | |

| Coniferus | 21 | 9.25 | ||

| Mixed | 23 | 10.13 | ||

| NA | 118 | 51.98 | ||

| Managing Orgnanization | Type of Organization | Private Nonprofit | 127 | 54.74 |

| Private for Businesses | 74 | 31.89 | ||

| Public | 14 | 6.03 | ||

| Public–Private | 15 | 6.46 | ||

| NA | 2 | 0.86 | ||

| Actors | Civil Society or Individuals | 179 | 77.15 | |

| Governance or Public Bodies | 9 | 3.87 | ||

| Academic or Technical Bodies | 2 | 0.86 | ||

| Mixed | 41 | 17.67 | ||

| NA | 1 | 0.43 | ||

| Source of Information | Scientific Literature | 0 | 0 | |

| Gray Literature | 8 | 3.45 | ||

| Website | 196 | 84.48 | ||

| Personal Contact | 28 | 12.07 | ||

| Typology | N (%) of Cases Identified within the Repository | Description | Category | Contributions to Health and Activities Supported | Target Users | Environment Substitutability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest-based Therapy (FT) | 9 (4%) | FCIs focused on treatment and rehabilitation practices, based on contact with forest ecosystems and requiring direct involvement and collaboration of the health sector. Therapies are transferred and adapted to the forest environment with the collaboration of different areas of expertise. | Therapy and rehabilitation | Physiological, psychological, and social | Special needs Assisted |

|

| Social Inclusion (SI) | 19 (8%) | FCIs aimed at providing marginalized groups of people with inclusive opportunities for improving social and emotional skills, or specific working skills, reducing inequalities in the access to nature with the final objective to promote their social integration. This is normally achieved via measures delivered by trained professionals (non-clinical services). | Prevention and Promotion | Social (and psychological) | Special needs Assisted |

|

| Wellness (WELL) | 64 (28%) | FCIs promoting healthy lifestyles through light physical activities and sensory experiences in the woodlands, such as forest bathing, mindfulness, breathing exercises, forest spas, yoga, and other activities for relaxation and personal growth in the forest. Such initiatives encourage a soulful connection with nature, prevent stress and technostress, and support mental restoration. | Prevention and Promotion | Psychological (and physiological) | General public Assisted |

|

| Education (EDU) | 89 (38%) | FCIs involving experience-oriented learning in nature, environmental education, active engagement with natural elements to develop gross and fine motor abilities, inspiration of creativity and imagination through interaction with natural environments, and stimulating positive behaviors toward nature. FCIs falling within this typology are mainly, but not only, addressed to children and young kids. | Synergic benefits | Social | Specific target Assisted |

|

| Artistic and Cultural Inspiration (ART) | 38 (16%) | FCIs where forest and woodland areas are transformed into open-air museums, populated by site-specific art pieces or by private collections displayed in the natural environment. Woodlands used as stages for concerts, theatrical pieces, and workshops are also included. | Synergic benefits | Social | General public Self-leading |

|

| Services for the Community (SOCIAL) | 8 (3%) | FCIs aimed at enhancing social cohesion, creating a sense of community while actively engaged in forest management. This includes everything from social forestry to initiatives in which the forest nurtures spiritual values and through the creation of burial forests or by hosting spiritual communities and their deities. Community food forests also fall under this category, providing organic food, opportunities for learning about sustainable agricultural practices, occasions for social contact and bonding, enhancing the sense of place, and a refuge from urban routine and stress. | Synergic benefits | Social | General public Self-leading |

|

| Wilderness and Adventure (WILD) | 5 (2%) | FCIs offering, especially to city-dwellers with decreasing occasions for deep contact with nature, the opportunity to stay in the wild while experiencing a sense of adventure. Such initiatives offer unique opportunities to interact with nature in the wild and learn new skills, from survival to fine motricity and collaborative problem-solving. | Synergic benefits | Social | General public Assisted |

|

| Categories | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Treatment and Rehabilitation | Initiatives created in close collaboration with the health sector and professionals, where specific characteristics of the forest environment are used to develop ad hoc treatments, rehabilitation, and integrative therapies tailored for specific health conditions (both physical and psychological). Though not exclusively, they tend to address small groups of people with homogenous needs and are often proposed as a program rather than one-off visits. Objectives, activities, and the use of the forest environment tend to be tuned to target users ‘needs. |

| Prevention and Promotion of Health and Wellbeing | Initiatives using the forest environment, taking advantage of the positive effects of forest exposure via specific activities and approaches for health promotion and preventive purposes (i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention). Such services are delivered to a large population, both with one-off and recurrent visits. The involvement of the health sector is not strictly necessary, as clinical services and the assistance of professional doctors are not needed. |

| Synergic (Wellbeing Benefits) | Initiatives not aimed at providing specific health outcomes, but rather at enriching the social dimension of wellbeing while providing indirect or collateral health benefits through contact with the forest ecosystem. They enable the creation of synergies between the forest, health, and other sectors, supporting cross-sector collaborations across the education, tourism, recreation, and art and culture sectors. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doimo, I.; Masiero, M.; Gatto, P. Disentangling the Diversity of Forest Care Initiatives: A Novel Research Framework Applied to the Italian Context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020492

Doimo I, Masiero M, Gatto P. Disentangling the Diversity of Forest Care Initiatives: A Novel Research Framework Applied to the Italian Context. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020492

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoimo, Ilaria, Mauro Masiero, and Paola Gatto. 2021. "Disentangling the Diversity of Forest Care Initiatives: A Novel Research Framework Applied to the Italian Context" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020492

APA StyleDoimo, I., Masiero, M., & Gatto, P. (2021). Disentangling the Diversity of Forest Care Initiatives: A Novel Research Framework Applied to the Italian Context. Sustainability, 13(2), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020492