Does China’s Low-Carbon Pilot Policy Promote Foreign Direct Investment? An Empirical Study Based on City-Level Panel Data of China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

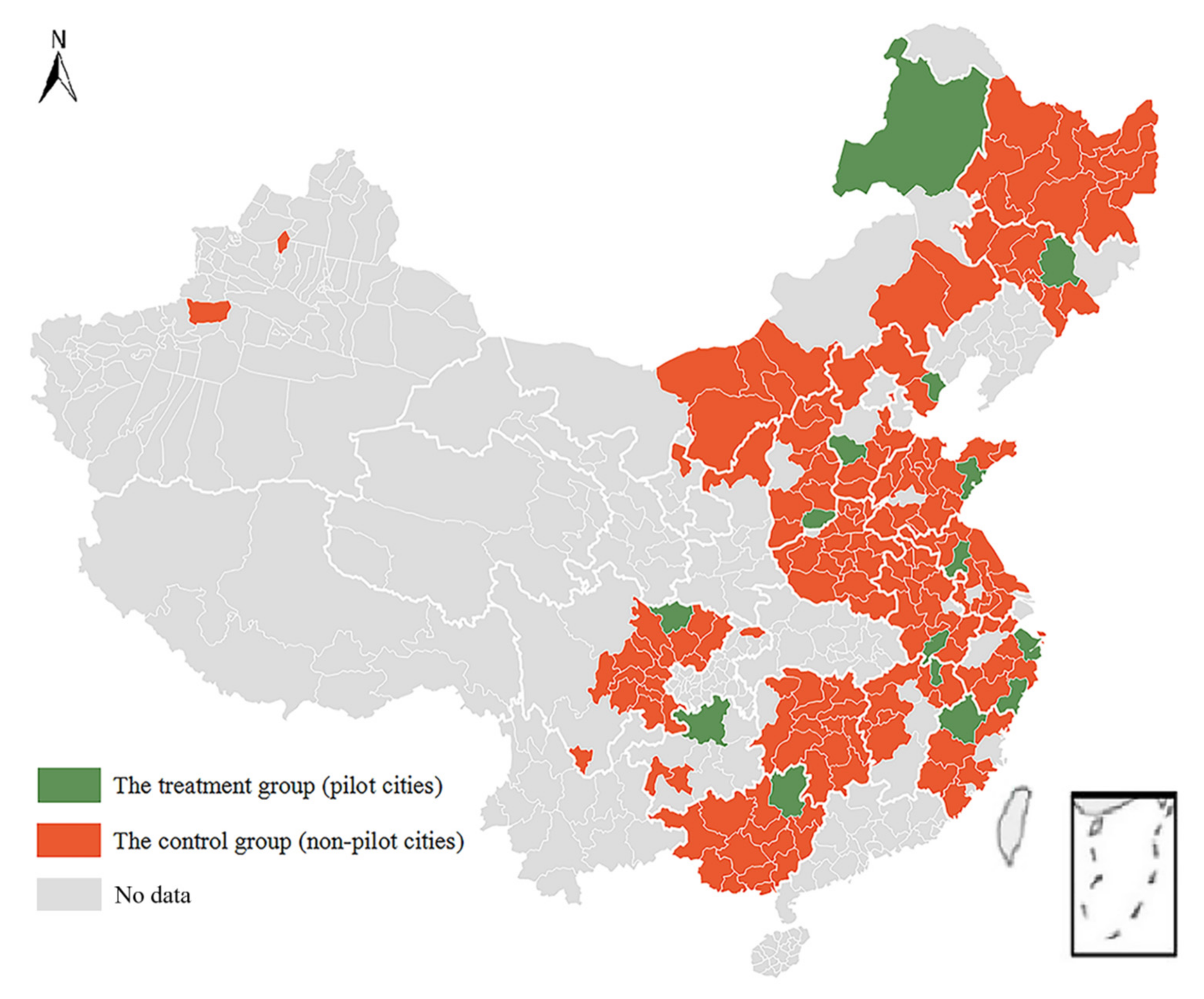

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Benchmark Regression Model Construction

3.2. Research Hypothesis

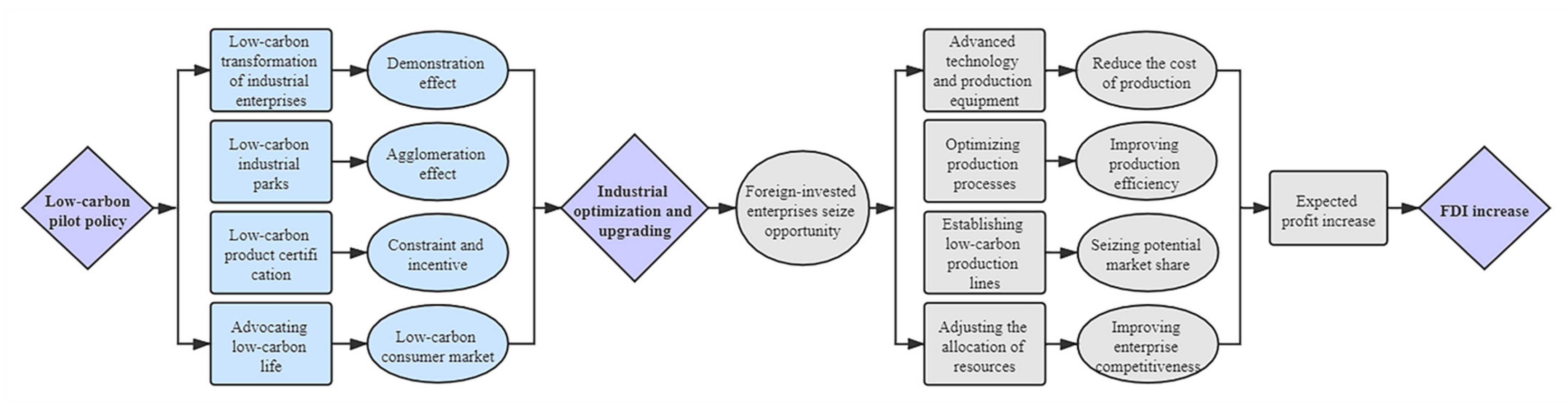

3.2.1. Impact of Low-Carbon Pilot Policy on FDI

3.2.2. Intermediary Mechanism of Policy Effect

- (1)

- Promoting the transformation and upgrading of traditional high-pollution industries, and continuously optimizing the foreign investment environment. In order to accelerate the low-carbon transformation of high-carbon industries, pilot cities will strictly control the production capacity of traditional industries and accelerate the elimination of backward industrial production capacity and technical equipment, such as iron and steel, cement, coal, smelting and casting, chemicals, and building materials. In the process of vigorously promoting the transformation and upgrading of traditional high-pollution industries, local governments will introduce a series of preferential policies and supporting services, increase support for low-carbon industries and projects, and improve the proportion of investment in advanced technology and green production equipment. These measures will create a favorable investment environment for foreign-invested enterprises;

- (2)

- Giving full play to the demonstration role of low-carbon transformation of industrial enterprises and the agglomeration effect of low-carbon industrial parks, and striving to guide FDI into low-carbon projects. With the support of national and provincial policies and funds, pilot cities will give priority to approving low-carbon demonstration projects, build low-carbon industrial parks, support the promotion and application of low-carbon products and low-carbon technologies, and promote the low-carbon transformation of industrial enterprises. The resulting agglomeration effect can further improve the production efficiency, market competitiveness and expected profits of foreign-invested enterprises, thus gradually forming a virtuous circle of attracting foreign investment;

- (3)

- Pilot cities will gradually establish systems of low-carbon product certification and carbon labeling, formulate standards for production and sale of low-carbon product, and guide residents to low-carbon consumption, thus creating a new market for low-carbon product. With advanced production technology and equipment, as well as low-carbon production lines, foreign-invested enterprises are more competitive in the low-carbon market. Therefore, in the face of development opportunities brought about by the optimization and upgrading of traditional industries, foreign-invested enterprises will actively transform production decision-making and investment fields, accelerate the adjustment of resource allocation and product structure, and optimize production processes, thus gaining more market share and profits.

3.3. Variable and Data

- (1)

- City size: City size will affect the economic output efficiency, resource integration and recycling capacity of the city, which is measured by the number of the household registered population at year-end. As city size expands, the agglomeration of advanced production factors will enhance the diversity of the city’s economic structure, market vitality, technological innovation, and urban functions [53]. The resulting scale effect and positive externalities will effectively reduce the production, financing, and transaction costs of foreign-invested enterprises. In addition, for larger cities, centrally control pollution (e.g., treatment of three wastes) and improve the effect of emission reduction become possible [54];

- (2)

- Trade openness: As an important factor affecting foreign direct investment [55], trade openness usually manifests itself as market opening starting from the commodity market, which is reflected in all aspects of international trade [56]. Given that multinational companies are more willing to invest in countries and regions with a higher degree of openness, increasing trade openness will help attract a large amount of international capital. This paper uses the ratio of the total export–import volume to GDP to measure trade openness;

- (3)

- Labor cost can be measured by the average wage of employed staff and workers. Many studies have shown that labor cost is an important factor that affects the investment decision-making of foreign-invested enterprises [57]. On the one hand, higher labor cost means that foreign-invested companies will pay higher production costs, thus stimulating capital to flow into countries and regions with lower labor cost [58]. On the other hand, higher labor cost means higher labor productivity, which helps to attract FDI [57]. Therefore, investors will inevitably face a trade-off between cost and efficiency when making investment decisions;

- (4)

- Human capital. Abundant human capital and the resulting talent advantages help to promote production, improve production efficiency and management efficiency, and reduce enterprise costs. Therefore, foreign-invested enterprises are more inclined to choose regions with rich human capital when investing. We use the total enrollment of regular higher education institutions to measure human capital. It is worth noting that, referring to the definition of Crane and Hartwell (2019), the term of “talent” mentioned in this study is defined as the combined human capital and social capital that an individual possesses [59];

- (5)

- Maturity of financial market can be measured by the ratio of loans of the national banking system at year-end to GDP. As an investment hub and intermediary, domestic credit provided by the financial sector has become an important financing factor for attracting FDI [60].

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Regression Results

4.2. Tests of Intermediary Mechanism

4.3. Robustness Test

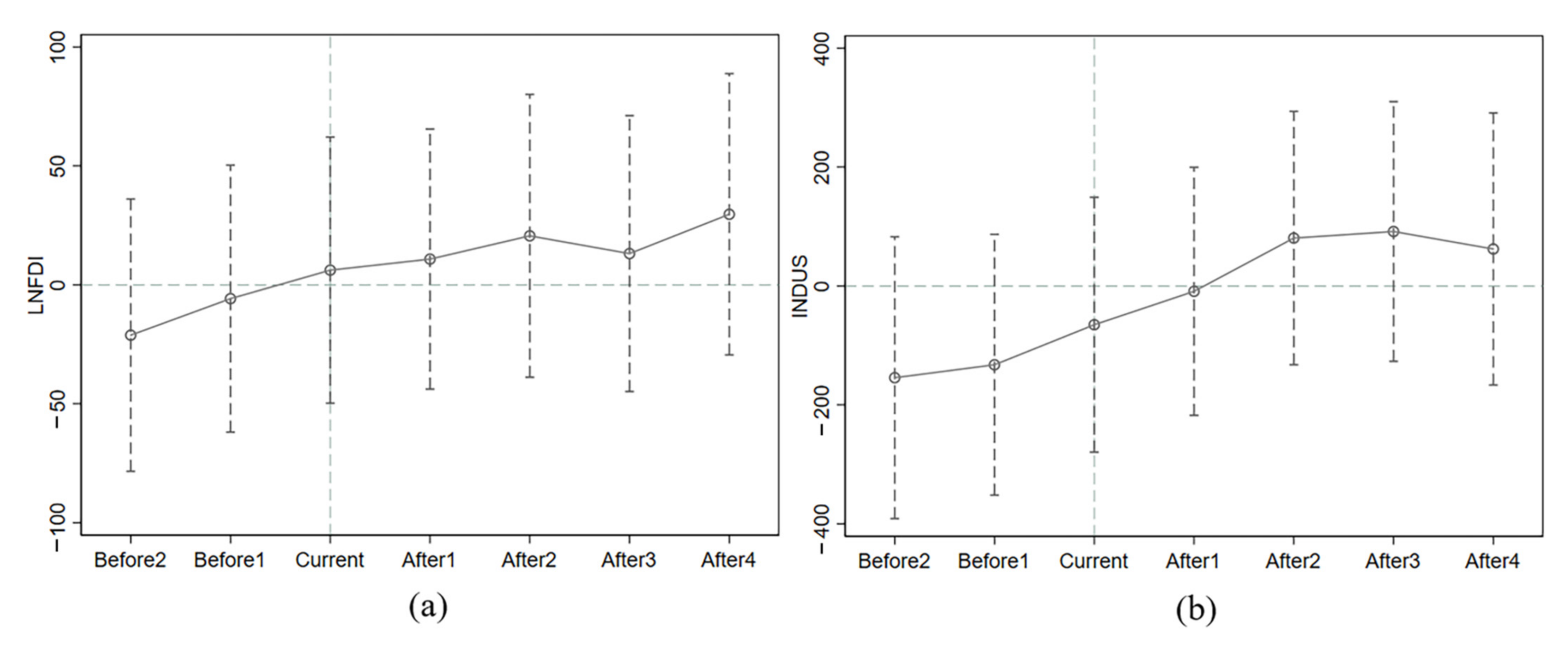

4.3.1. Parallel Trend Test

4.3.2. Placebo Test: The Influence of Random Factors

4.3.3. Placebo Test: The Influence of Other Policies in the Same Period

4.3.4. The Influence of the Dependent Variable Outliers

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Differences in Resource Endowments

5.2. Differences in Individual Characteristics of Government Officials

- (1)

- Gender of the mayor: In column (2) of Table 6, the coefficient of is 0.6520, and is significant at the 5% level. This implies that compared with cities where the mayor is a male, the policy effect of a female-administered city is greater. It is a very interesting finding. According to existing research, we suppose that it may be because, on average, female leaders may be more assertive and better at managing resources and public goods [65], thus achieving better results in maintaining social stability and improving social outcomes [66]. In addition, compared with male leaders, female leaders may be more inclined to democratic and participatory leadership styles, which makes them have the natural advantage of becoming charismatic leaders. During the implementation of the low-carbon pilot policy, by shaping the image of exceptional competence, female leaders will more easily mobilize the initiative of policy executors [67], and more effectively improve the management efficiency and organizational efficiency of the local government. Therefore, with the efficient and continuous release of the low-carbon policy’ effectiveness, the investment motivation of foreign-invested enterprises will be further stimulated;

- (2)

- Educational background of the mayor: Observing column (3) of Table 6, when the mayor obtains a master’s degree or a doctor’s degree, the coefficient of is 0.4143, and is significantly positive at the 10% level. This indicates that compared with cities where mayors obtain bachelor’s degrees, mayors who obtain graduate degrees will more effectively play the promotion effect of low-carbon pilot policy on FDI. Environmental governance is a long-term, complex, and dynamic system engineering, which involves the entire process management of pre-prevention, mid-term supervision, and post-governance, and is closely related to economic development, social harmony, and residents’ health. Therefore, in the context of low-carbon city construction, after long-term and more systematic training and learning, leaders can make better use of environmental policy instruments (e.g., finance, taxation, and subsidies), fully release policy dividends, and continuously stimulate the market vitality, thus creating a more attractive investment environment;

- (3)

- Mayor’s major: For column (4) of Table 6, the coefficient of is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that in cities where mayors majored in non-economics, a low-carbon pilot policy can promote FDI more significantly. As mentioned in previous studies, during the period in power, mayors who majored in economics may pay more attention to short-term economic benefits [68] and prefer to achieve regional economic growth goals by using direct policy measures. Therefore, the low-carbon pilot policy, as an environmental regulation that indirectly promotes economic growth, may be ignored to a certain extent. However, for mayors who majored in non-economics, how to obtain sustainable economic benefits without destroying the ecological environment has been put on the agenda. Under the background of accelerating the construction of low-carbon cities, pilot cities can actively strive for national and provincial funds, and vigorously attract FDI through strong preferential measures, so as to make up for environmental governance costs and pollution control costs.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Under the special background of increasing downward pressure of economy, local governments should give full play to the leverage of low-carbon pilot policy, comprehensively use environmental policy tools (e.g., finance, taxation, trade, government procurement), and encourage foreign-invested enterprises to invest in low-carbon projects and participate in the development and utilization of clean energy, low-carbon technologies, and low-carbon products. At the same time, local governments should accelerate the construction of green industrial parks and closed loops of the entire industry chain, vigorously promote the transformation and upgrading of traditional industries, and make full use of cluster advantages and scale effect to create new growth poles for foreign-invested enterprises;

- (2)

- Pilot cities, especially those with good resource endowments, should seize the opportunity of low-carbon city construction, use resource advantages to develop advantageous industries, promote the construction of key emission reduction projects, and encourage foreign-invested enterprises to open branches and build large-scale factories. It is worth noting that urban environmental governance and economic development are highly dependent on government officials. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the training of the working ability of government officials, encourage government officials to exchange experience and continue their further studies, and continuously improve their urban governance ability and comprehensive quality. In addition, the important role of female leaders in the construction of low-carbon cities also needs more attention and discussion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. The impacts of GDP, trade structure, exchange rate and FDI inflows on China’s carbon emissions. Energy Policy 2018, 120, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F.; Tan, B.W. The impact of energy consumption, income and foreign direct investment on carbon dioxide emissions in Vietnam. Energy 2015, 79, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, F.; Mirzaei, P.A. Impact of non-uniform urban surface temperature on pollution dispersion in urban areas. Build. Simul. 2011, 4, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, G.; Uddin, K.; Guo, S. Environmental regulation, Foreign investment behavior, and carbon emissions for 30 provinces in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, G. Command without control: The case of China’s environmental target system. Regul. Gov. 2016, 10, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Could environmental regulation and R&D tax incentives affect green product innovation? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zayat, H.; Ibraheem, G.; Kandil, S. The response of industry to environmental regulations in Alexandria, Egypt. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisitano, I.M.; Biglia, A.; Fabrizio, E.; Filippi, M. Building for a Zero Carbon future: Trade-off between carbon dioxide emissions and primary energy approaches. Energy Procedia 2018, 148, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Guo, H. Does central supervision enhance local environmental enforcement? Quasi-experimental evidence from China. J. Public Econ. 2018, 164, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Zeng, H.; Fu, S. Local government responses to catalyse sustainable development: Learning from low-carbon pilot programme in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 689, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T. A holistic overview of the progress of China’s low-carbon city pilots. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; He, C.; Luo, L. Does the low-carbon city policy make a difference? Empirical evidence of the pilot scheme in China with DEA and PSM-DID. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, X. Pilot Implementation Mechanism from the Perspective of Policy Ambiguity: A Case Study of the Pilot Policy of Low-Carbon Cities. Truth Seek 2020, 2, 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S. The policy outcomes of low-carbon city construction on urban green development: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment conducted in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Qin, M.; Wang, R.; Qi, Y. How does the nested structure affect policy innovation? Empirical research on China’s low carbon pilot cities. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, X.; Yin, S.; Chen, W. Low-carbon development quality of cities in China: Evaluation and obstacle analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 64, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Guo, W.; Feng, X.; Wei, W.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y.; Gong, W. The impact of low-carbon city pilot policy on the total factor productivity of listed enterprises in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Deng, X. Impacts and mitigation of climate change on Chinese cities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, H.T. To shut down or to shift: Multinationals and environmental regulation. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 102, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.S. Unbundling the Pollution Haven Hypothesis. Adv. Econ. Anal. Policy 2005, 3, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnermeier, S.B.; Levinson, A. Examining the Evidence on Environmental Regulations and Industry Location. J. Environ. Dev. 2004, 13, 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulatu, A.; Gerlagh, R.; Rigby, D.; Wossink, A. Environmental Regulation and Industry Location in Europe. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2010, 45, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Song, D. How does environmental regulation break the resource curse: Theoretical and empirical study on China. Resour. Policy 2019, 64, 101480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.J.R.; Zhou, Y. Environmental Regulation Induced Foreign Direct Investment. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2013, 55, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Econ. Costs Conseq. Environ. Regul. 1995, 9, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.R.; Dash, D.P. The effect of urbanization, energy consumption, and foreign direct investment on the carbon dioxide emission in the SSEA (South and Southeast Asian) region. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, B.; Khan, S. Effect of bilateral FDI, energy consumption, CO2 emission and capital on economic growth of Asia countries. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuma, K. An Analytical Framework for the Relationship between Environmental Measures and Economic Growth Based on the Régulation Theory: Key Concepts and a Simple Model. Evol. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2012, 9, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Gerlowski, D.A.; Silberman, J. What Attracts Foreign Multinational Corporations? Evidence from Branch Plant Location in the United States. J. Reg. Sci. 1992, 32, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, A. Environmental regulations and manufacturers’ location choices: Evidence from the Census of Manufactures. Econ. Costs Conseq. Environ. Regul. 1996, 62, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskeland, G.S.; Harrison, A.E. Moving to greener pastures? Multinationals and the pollution haven hypothesis. J. Dev. Econ. 2003, 70, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.; Krueger, A. Economic Growth and the Environment. Econ. Growth Environ. 1994, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Kolstad, C.D. Do Lax Environmental Regulations Attract Foreign Investment? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2002, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, J.; Song, H.J.; Lee, S. Impact of short-term rental regulation on hotel industry: A difference-in-differences approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Lu, Y.; Wu, M.; Yu, L. Does environmental regulation drive away inbound foreign direct investment? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Percival, R. Comparative Environmental Federalism: Subsidiarity and Central Regulation in the United States and China. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2017, 6, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, S.; He, C. How do environmental regulations affect industrial dynamics? Evidence from China’s pollution-intensive industries. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, M. Does FDI Promote MENA Region’s Environment Quality? Pollution Halo or Pollution Haven Hypothesis. Int. J. Sci. Res. Environ. Sci. 2013, 1, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, D. The effects of environmental regulation on outward foreign direct investment’s reverse green technology spillover: Crowding out or facilitation? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtoo, A.; Antony, S. Environmental regulations. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2007, 18, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Solecki, W.D.; Hammer, S.A.; Mehrotra, S. Cities lead the way in climate–change action. Nature 2010, 467, 909–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Guan, D.; Hubacek, K.; Zheng, B.; Davis, S.J.; Jia, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Fromer, N.; Mi, Z.; et al. City-level climate change mitigation in China. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaaq0390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolstad, I.; Wiig, A. What determines Chinese outward FDI? J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y. Effect of environmental regulation policy tools on the quality of foreign direct investment: An empirical study of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonigen, B.A.; Piger, J. Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment. Found. Essays Econ. Immigr. 2019, 6, 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomström, M.; Kokko, A.; Mucchielli, J.-L. The Economics of Foreign Direct Investment Incentives. In Foreign Direct Investment in the Real and Financial Sector of Industrial Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y. Causal links between foreign direct investment and trade in China. China Econ. Rev. 2001, 12, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, N.; Lensink, R. Foreign direct investment, financial development and economic growth. J. Dev. Stud. 2003, 40, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Singhania, M. Determinants of FDI in developed and developing countries: A quantitative analysis using GMM. J. Econ. Stud. 2018, 45, 348–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratzscher, M. Capital flows, push versus pull factors and the global financial crisis. J. Int. Econ. 2012, 88, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfatia, H.A. The Role of Push and Pull Factors in Driving Global Capital Flows. Appl. Econ. Q. 2016, 62, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Sharma, A.K. Determinants of foreign direct investment in developing countries: A panel data study. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2017, 12, 658–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romić, I. Functional diversity in Keihanshin Metropolitan Area. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2018, 5, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shang, Y.; Song, M. What kind of cities are more conducive to haze reduction: Agglomeration or expansion? Habitat Int. 2019, 91, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N. Democratic Governance and Multinational Corporations: Political Regimes and Inflows of Foreign Direct Investment. Int. Organ. 2003, 57, 587–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, I.A.; Cardak, B. The determinants of foreign direct investment: An extreme bounds analysis. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2006, 16, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbakhsh, F.; Paloni, A.; Youssef, A. Human Capital and FDI Inflows to Developing Countries: New Empirical Evidence. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1593–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuka, K.O. Wage rate, regional trade bloc and Location of Foreign Direct Investment Decisions. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2011, 1, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, B.; Hartwell, C.J. Global talent management: A life cycle view of the interaction between human and social capital. J. World Bus. 2019, 54, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, O. Maximising international returns: Impact of IFRS on foreign direct investments. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2020, 16, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, D.; Panousi, V. Investment, Idiosyncratic Risk, and Ownership. SSRN Electron. J. 2011, 67, 1113–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gulen, H.; Ion, M. Policy Uncertainty and Corporate Investment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 29, 523–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-C.; Boarelli, S.; Vu, T.H.C. The effects of economic policy uncertainty on outward foreign direct investment. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2019, 64, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, N. Low-carbon city pilot and carbon emission efficiency: Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2021, 96, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steimanis, I.; Hofmann, R.; Mbidzo, M.; Vollan, B. When female leaders believe that men make better leaders: Empowerment in community-based water management in rural Namibia. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadharan, L.; Jain, T.; Maitra, P.; Vecci, J. Female leaders and their response to the social environment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2019, 164, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Yuan, Y. Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on energy efficiency in the industrial sector: Evidence from Chinese provincial data. Energy Policy 2020, 145, 111747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predicted Relationship | Symbol | Variable | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | LNFDI | Foreign Direct Investment | Total Amount of Foreign |

| Investment Actually Utilized | |||

| Independent Variable | Low-carbon City Pilot | Pilot Cities | |

| LNSIZE | City Size | Household Registered Population at Year-end | |

| Control Variables | OPEN | Trade Openness | Total Export-import Volume/GDP |

| LNWAGES | Labor Cost | Average Wage of Employed Staff and Workers | |

| HUMCAP | Human Capital | Total Enrollment of Regular Higher Education Institutions | |

| LOANS | Maturity of Financial Market | Loans of National Banking System at Year-end/GDP | |

| Mediating variable | INDUS | Industrial optimization and upgrading | Added Value of the Second Industry/GDP |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNFDI | 1512 | 11.94433 | 1.609704 | 2.892627 | 15.77754 |

| 1512 | 0.0595238 | 0.2366807 | 0 | 1 | |

| LNSIZE | 1512 | 5.946699 | 0.645489 | 3.400197 | 7.297091 |

| OPEN | 1512 | 14.45804 | 21.1027 | 0.0505215 | 230.3771 |

| LNWAGES | 1512 | 10.74825 | 0.2549521 | 9.75314 | 12.67803 |

| HUMCAP | 1512 | 10.49283 | 1.413236 | 0 | 13.80897 |

| LOANS | 1512 | 89.55015 | 60.97874 | 6.585535 | 782.3959 |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Human Capital | 1.67 | 0.600411 |

| City Size | 1.47 | 0.681131 |

| Labor Cost | 1.26 | 0.794691 |

| Maturity of Financial Market | 1.19 | 0.842696 |

| Trade Openness | 1.09 | 0.919785 |

| 1.03 | 0.973528 | |

| Mean VIF | 1.28 |

| Variable | DID | Tests of Intermediary Mechanism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDI | INDUS | FDI | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| 0.3776 ** (0.1699) | 0.0088 (0.1310) | 0.2614 ** (0.1151) | 0.2691 ** (0.1139) | 1.7002 *** (0.5371) | 0.2188 * (0.1145) | |

| INDUS | 0.0296 *** (0.0087) | |||||

| _cons | 11.9219 *** (0.0427) | −0.4738 (1.6095) | 12.9985 *** (0.1574) | 2.2535 (4.3561) | −33.9648 (31.9480) | 3.2595 (4.0350) |

| Control Variable | NO | Control | NO | Control | Control | Control |

| year-fixed effects | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| city-fixed effects | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.0031 | 0.3385 | 0.8287 | 0.8308 | 0.9228 | 0.8334 |

| N | 1512 | 1512 | 1512 | 1512 | 1512 | 1512 |

| FDI | Data Truncation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| 0.2204 * (0.1156) | 0.2280 * (0.1293) | 0.3081 ** (0.1354) | |

| _cons | 5.3422 (3.4856) | 5.3648 (3.5469) | 5.4201 (3.5473) |

| Control Variable | Control | Control | Control |

| year-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| city-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.8572 | 0.8385 | 0.8198 |

| N | 1481 | 1422 | 1346 |

| FDI | Resource Endowment | Individual Characteristics of Government Officials | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Region | Gender | Educational | Major | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 0.7793 *** | ||||

| (0.2977) | ||||

| 0.6520 ** | ||||

| (0.2638) | ||||

| 0.4143 * | ||||

| (0.2343) | ||||

| 0.3995 *** | ||||

| (0.1412) | ||||

| _cons | 1.4448 | 2.6832 | 3.1901 | 5.6229 |

| (4.3472) | (4.3054) | (3.2239) | (3.5542) | |

| Control Variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| year-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| city-fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.8346 | 0.8317 | 0.8311 | 0.8213 |

| N | 1512 | 1512 | 1512 | 1512 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, C.; Wang, B. Does China’s Low-Carbon Pilot Policy Promote Foreign Direct Investment? An Empirical Study Based on City-Level Panel Data of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910848

Zhao C, Wang B. Does China’s Low-Carbon Pilot Policy Promote Foreign Direct Investment? An Empirical Study Based on City-Level Panel Data of China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910848

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Chang, and Bing Wang. 2021. "Does China’s Low-Carbon Pilot Policy Promote Foreign Direct Investment? An Empirical Study Based on City-Level Panel Data of China" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910848

APA StyleZhao, C., & Wang, B. (2021). Does China’s Low-Carbon Pilot Policy Promote Foreign Direct Investment? An Empirical Study Based on City-Level Panel Data of China. Sustainability, 13(19), 10848. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910848