LEED 2009 Recertification of Existing Buildings: Bonus Effect

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Replication Method

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

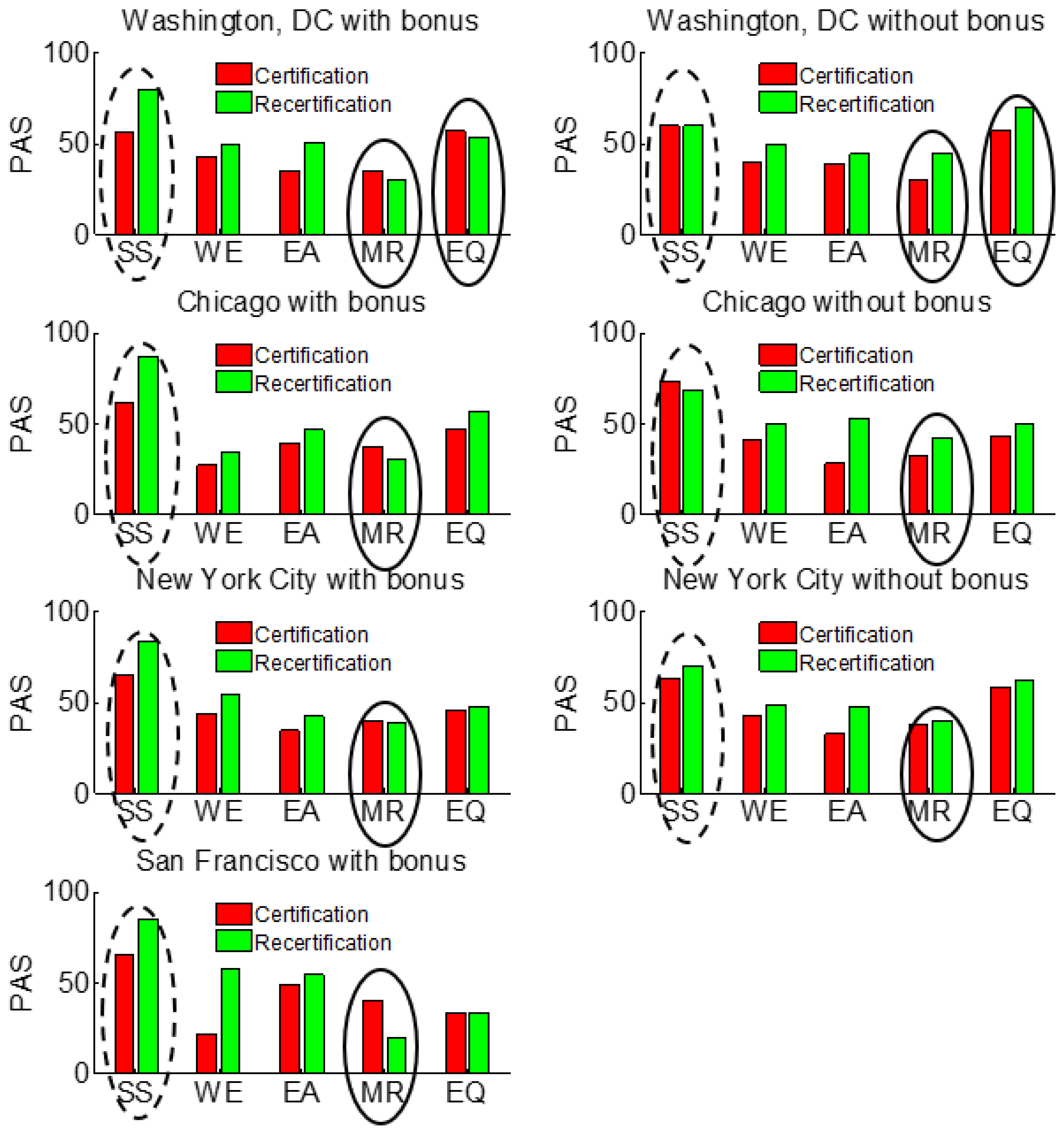

3.1. Gold Certification–Recertification with Bonus and without Bonus

3.2. Silver Certification–Gold Recertification with Bonus and without a Bonus

3.3. Platinum Certification–Recertification with Bonus

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WBCSD 2018. SBT4 Buildings: A Framework for Carbon Emissions Management along the Building and Construction Value Chain, World Business Council for Sustainable Development. 2018. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/Programs/Cities-and-Mobility/Sustainable-Cities/Science-based-targets/Resources/framework-carbon-emissions-management-building-construction-value-chain (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Sartori, T.; Drogemuller, R.; Omrani, S.; Lamari, F. A schematic framework for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Green Building Rating System (GBRS). J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Realff, M.J. The design of a sustainability assessment standard using life cycle information. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 17, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierra, S. Green Building Standards and Certification Systems vol. 27, Green Building Standards and Certification Systems. 2014. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/resources/green-building-standards-and-certification-systems (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Leung, B.C.-M. Greening existing buildings [GEB] strategies. Energy Rep. 2018, 4, 159–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matisoff, D.C.; Noonan, D.S.; Flowers, M.E. Policy monitor—Green buildings: Economics and policies. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy. 2016, 10, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenstein, W.; Fuertes, G.; Kaam, S.; Seigel, K.; Arens, E.; Mozingo, L. Climate co-benefits of green building standards: Water, waste and transportation. Build. Res. Inform. 2017, 45, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, H.; Handy, R.; Sleeth, D.; Matthew, S.; Schaefer, C.; Stubbs, J. Taking the “LEED” in Indoor Air Quality: Does Certification Result in Healthier Buildings? J. Green Build. 2020, 15, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J.H.; Brodnitz, S.; Cornell, J.; Liang, T.; Scofield, T. Energy and Greenhouse Gas Savings for LEED-Certified U.S. Office Buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekanye, O.G.; Davis, A.; Azevedo, I.L. Federal policy, local policy, and green building certifications in the U.S. Energy Build. 2020, 209, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Lib, H.; Feng, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, Q. Developing a green building evaluation standard for interior decoration: A case study of China. Build Environ. 2019, 152, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E. Green on buildings: The effects of municipal policy on green building designations in America’s central cities. J. Sustain. Real Estate 2010, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, N.; McGraw, M.; Quigley, J.M. The diffusion of energy efficiency in building. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simcoe, T.; Toffel, M.W. Government green procurement spillovers: Evidence from municipal building policies in California. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 68, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuerst, F.; Kontokosta, C.; McAllister, P. Determinants of green building adoption. Environ. Plan. B-Plan. Des. 2014, 41, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.G.; Vedula, S.; Lenox, M.J. It’s not easy building green: The impact of public policy, private actors, and regional logics on voluntary standards adoption. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1492–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, F. Building momentum: An analysis of investment trends in LEED and Energy Star-certified properties. J. Retail Leis. Prop. 2009, 8, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, P.; Mao, C.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.Z.; Wang, X.Y. A decade review of the credits obtained by LEED v2.2 certified green building projects. Build. Environ. 2016, 102, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Song, Y.Z.; Shou, W.C.; Chi, H.L.; Chong, H.Y.; Sutrisna, M. A comprehensive analysis of the credits obtained by LEED 2009 certified green buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68 Pt 1, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S.; Verbitsky, O. LEED-NCv3 Silver and Gold certified projects in the US: An observational study. J. Green Build. 2018, 13, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S.; Verbitsky, O. Silver and gold LEED commercial interiors: Certified projects. J. Green Build. 2019, 14, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, M.E.; Matisoff, D.C.; Noonan, D.S. In the LEED: Racing to the top in environmental self-regulation. Bus Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2842–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEED-EB 2009. LEED 2009 for Existing Buildings: Operations & Maintenance. Available online: https://energy.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/energynvgov/content/Progras/2009_EBOM.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- LEED-EBv4 2018 LEED v4 for Building Operations and Maintenance. Available online: http://greenguard.org/uploads/images/LEEDv4forBuildingOperationsandMaintenanceBallotVersion.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Trovato, M.R.; Francesco Nocera, F.; Giuffrida, S. Life-Cycle Assessment and Monetary Measurements for the Carbon Footprint Reduction of Public Buildings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- USGBC. Projects Site. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/projects (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- GBIG. The Green Building Information Gateway. Available online: http://www.gbig.org (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Meehl, P.E. Appraising and amending theories: The strategy of Lakatosian defense and two principles that warrant it. Psychol. Inq. 1990, 1, 108–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S. Sacrificial Pseudoreplication in LEED Cross-Certification Strategy Assessment: Sampling Structures. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, B.; Lu, W.; Ye, M.; Bao, Z.; Zhang, X. Construction waste minimization in green building: A comparative analysis of LEED-NC 2009 certified projects in the US and China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundry, R.; Fischer, J. Use of statistical programs for nonparametric tests of small samples often leads to incorrect P values: Examples from animal behaviour. Anim. Behav. 1998, 56, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pham, D.H.; Kim, B.; Lee, J.; Ahn, Y. An Investigation of the Selection of LEED Version 4 Credits for Sustainable Building Projects. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LEED-EB 2009 Office Space Project (Certification-Recertification on the Same Building) | Number of Paired Projects Identified | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington, DC | Chicago | New York | San Francisco | |

| Platinum-platinum with bonus 1 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Platinum-platinum without bonus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gold-gold with bonus 1 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| Gold-gold without bonus 1 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Silver-silver with bonus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Silver-silver without bonus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Certified-certified with bonus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Certified-certified without bonus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gold-platinum with bonus | 7 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Gold-platinum without bonus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Silver-gold with bonus 1 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 |

| Silver-gold without bonus 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Certified-silver with bonus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Certified-silver without bonus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Certified-gold with bonus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Certified-gold without bonus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Certified-platinum with bonus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Silver-gold-platinum without bonus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Gold-certified with bonus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Credit 1 | Points | with Bonus | without Bonus | with Bonus | without Bonus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | ||

| Washington, DC | Chicago | ||||||||

| MRc1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| MRc2.1 | 1 | 31 | 15 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 17 | 25 | 25 |

| MRc2.2 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 17 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| MRc3 | 1 | 31 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 33 | 0 | 25 | 25 |

| MRc4 | 1 | 77 | 92 | 78 | 89 | 83 | 67 | 100 | 75 |

| MRc5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRc6 | 1 | 92 | 77 | 100 | 56 | 67 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| MRc7 | 1 | 46 | 23 | 11 | 44 | 67 | 17 | 50 | 0 |

| MRc8 | 1 | 85 | 85 | 89 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| MRc9 | 1 | 46 | 15 | 44 | 33 | 50 | 17 | 50 | 75 |

| New York City | San Francisco | ||||||||

| MRc1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| MRc2.1 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| MRc2.2 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| MRc3 | 1 | 13 | 13 | 20 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRc4 | 1 | 88 | 63 | 0 | 60 | 80 | 80 | 100 | 50 |

| MRc5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRc6 | 1 | 88 | 75 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 |

| MRc7 | 1 | 88 | 88 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 50 | 100 |

| MRc8 | 1 | 88 | 88 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 50 |

| MRc9 | 1 | 25 | 25 | 40 | 40 | 80 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Credit 1 | Points | with Bonus | without Bonus | with Bonus | without Bonus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | ||

| Washington, DC | Chicago | ||||||||

| EQc1.1 | 1 | 92 | 77 | 89 | 100 | 100 | 53 | 75 | 100 |

| EQc1.2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EQc1.3 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EQc1.4 | 1 | 92 | 92 | 89 | 89 | 83 | 63 | 75 | 100 |

| EQc1.5 | 1 | 54 | 38 | 11 | 22 | 17 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| EQc2.1 | 1 | 54 | 62 | 67 | 56 | 100 | 33 | 75 | 50 |

| EQc2.2 | 1 | 92 | 92 | 67 | 44 | 83 | 67 | 50 | 75 |

| EQc2.3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EQc2.4 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 50 | 33 | 0 | 25 |

| EQc3.1 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| EQc3.2 | 1 | 100 | 92 | 89 | 89 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 |

| EQc3.3 | 1 | 100 | 92 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75 |

| EQc3.4 | 1 | 100 | 92 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 100 | 75 |

| EQc3.5 | 1 | 62 | 69 | 67 | 22 | 50 | 67 | 0 | 50 |

| EQc3.6 | 1 | 85 | 54 | 89 | 67 | 67 | 83 | 75 | 100 |

| New York City | San Francisco | ||||||||

| EQc1.1 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 20 | 80 | 100 |

| EQc1.2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 100 |

| EQc1.3 | 1 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 50 | 0 |

| EQc1.4 | 1 | 88 | 68 | 60 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 100 | 100 |

| EQc1.5 | 1 | 25 | 0 | 20 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| EQc2.1 | 1 | 25 | 15 | 60 | 80 | 40 | 10 | 80 | 100 |

| EQc2.2 | 1 | 63 | 38 | 20 | 40 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| EQc2.3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EQc2.4 | 1 | 13 | 11 | 40 | 60 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| EQc3.1 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| EQc3.2 | 1 | 88 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 50 | 50 |

| EQc3.3 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 100 |

| EQc3.4 | 1 | 88 | 68 | 60 | 80 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 50 |

| EQc3.5 | 1 | 88 | 88 | 80 | 80 | 60 | 70 | 0 | 50 |

| EQc3.6 | 1 | 75 | 50 | 100 | 80 | 90 | 60 | 60 | 100 |

| Credit 1 | Points | with Bonus | without Bonus | with Bonus | without Bonus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | ||

| Washington, DC | Chicago | ||||||||

| MRc1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRc2.1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| MRc2.2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 25 |

| MRc3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRc4 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 50 | 0 | 75 |

| MRc5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRc6 | 1 | 100 | 75 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 25 | 100 | 100 |

| MRc7 | 1 | 75 | 25 | 50 | 70 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 75 |

| MRc8 | 1 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 50 | 75 |

| MRc9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 75 | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| New York City | San Francisco | ||||||||

| MRc1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc2.1 | 1 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc2.2 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc3 | 1 | 29 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0.00 | - | - |

| MRc4 | 1 | 71 | 57 | 25 | 75 | 0 | 100 | - | - |

| MRc5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc6 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc7 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 75 | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| MRc8 | 1 | 71 | 86 | 75 | 75 | 100 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc9 | 1 | 14 | 14 | 25 | 50 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Credit 1 | Points | with Bonus | without Bonus | with Bonus | without Bonus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | ||

| Washington, DC | San Francisco | ||||||||

| MRc1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 20 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc2.1 | 1 | 63 | 38 | - | - | 40 | 20 | - | - |

| MRc2.2 | 1 | 63 | 38 | - | - | 80 | 20 | - | - |

| MRc3 | 1 | 38 | 25 | - | - | 80 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc4 | 1 | 75 | 88 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| MRc5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 20 | 0 | - | - |

| MRc6 | 1 | 100 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| MRc7 | 1 | 88 | 63 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| MRc8 | 1 | 100 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| MRc9 | 1 | 63 | 63 | - | - | 100 | 80 | - | - |

| Credit 1 | Points | with Bonus | without Bonus | with Bonus | without Bonus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | Cert | Recert | ||

| Washington, DC | San Francisco | ||||||||

| EQc1.1 | 1 | 88 | 100 | - | - | 80 | 0 | - | - |

| EQc1.2 | 1 | 25 | 0 | - | - | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| EQc1.3 | 1 | 38 | 13 | - | - | 80 | 40 | - | - |

| EQc1.4 | 1 | 100 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| EQc1.5 | 1 | 13 | 13 | - | - | 80 | 0 | - | - |

| EQc2.1 | 1 | 75 | 50 | - | - | 100 | 60 | - | - |

| EQc2.2 | 1 | 100 | 100 | - | - | 60 | 60 | - | - |

| EQc2.3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 20 | 0 | - | - |

| EQc2.4 | 1 | 63 | 63 | - | - | 80 | 80 | - | - |

| EQc3.1 | 1 | 88 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| EQc3.2 | 1 | 88 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| EQc3.3 | 1 | 100 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 100 | - | - |

| EQc3.4 | 1 | 100 | 100 | - | - | 80 | 80 | - | - |

| EQc3.5 | 1 | 100 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 80 | - | - |

| EQc3.6 | 1 | 100 | 88 | - | - | 100 | 80 | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pushkar, S. LEED 2009 Recertification of Existing Buildings: Bonus Effect. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910796

Pushkar S. LEED 2009 Recertification of Existing Buildings: Bonus Effect. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910796

Chicago/Turabian StylePushkar, Svetlana. 2021. "LEED 2009 Recertification of Existing Buildings: Bonus Effect" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910796

APA StylePushkar, S. (2021). LEED 2009 Recertification of Existing Buildings: Bonus Effect. Sustainability, 13(19), 10796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910796